Abstract

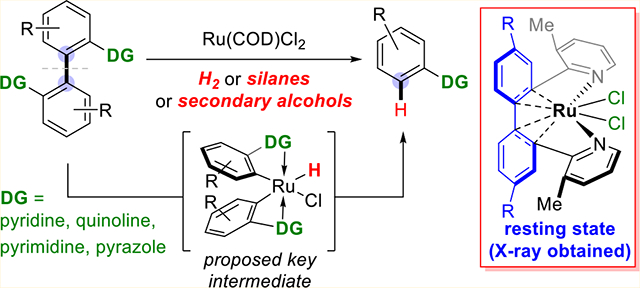

Cleavage of carbon–carbon bonds has been found in some important industrial processes, for example, petroleum cracking, and has inspired development of numerous synthetic methods. However, nonpolar unstrained C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds remain one of the toughest bonds to be activated. As a detailed study of a fundamental reaction mode, here a full story is described about our development of a Ru-catalyzed reductive cleavage of unstrained C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds. A wide range of biaryl compounds that contain directing groups (DGs) at 2,2′ positions can serve as effective substrates. Various heterocycles, such as pyridine, quinoline, pyrimidine, and pyrazole, can be employed as DGs. Besides hydrogen gas, other reagents, such as Hantzsch ester, silanes, and alcohols, can be employed as terminal reductants. The reaction is pH neutral and free of oxidants; thus a number of functional groups are tolerated. Notably, a one-pot C–C activation/C–C coupling has been realized. Computational and experimental mechanistic studies indicate that the reaction involves a ruthenium(II) monohydride-mediated C(aryl)–C(aryl) activation and the resting state of the catalyst is a η4-coordinated ruthenium(II) dichloride complex, which could inspire development of other transformations based on this reaction mode.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative addition of a transition metal (TM) into a carbon–carbon (C–C) bond represents an important means of activating C–C bonds, which has led to the development of numerous synthetically valuable methods.1 This process converts one relatively inert C–C bond into two more reactive C–TM bonds that can undergo further transformations, affording dual functionalization of both carbon terminuses (Scheme 1A).2 To date, a number of catalytic C–C cleavage/functionalization methods have been developed on the basis of such a mode of activation. However, the scope of C–C bonds that can undergo oxidative addition with TMs is still narrow (Scheme 1B). The major class of suitable substrates contains a three- or four-membered ring, in which strain release becomes the main driving force for the C–C cleavage.3 On the other hand, more polar C–C bonds, such as C–CN,4 C–carbonyl, and C–iminyl bonds in less strained substrates,5 can also be activated by low valent TMs due to favorable interactions between the low-lying σ* orbital in these moieties and TM filled d orbitals, which promotes forming the requisite C–C/TM σ complex.

Scheme 1. C–C Bond Activation via Oxidative Addition.

In contrast, TM insertion into nonpolar and unstrained C–C bonds has been extremely rare. In 1993, Milstein and co-workers reported a phosphine-directed activation of an aryl–alkyl bond in a pincer-type substrate, which was driven by forming a two–five-membered-fused rhodacycle (Scheme 2A).6 The catalytic transformation was also developed a few years later by the same group.7 Recently, Kakiuchi and co-workers developed a novel Rh-catalyzed cleavage of unstained aryl–allyl bonds, albeit through a β-carbon elimination mechanism.8 Activation of unstrained aryl–aryl bonds has been elusive9 until our recent work (Scheme 2B).10 The C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds in 2,2′-biphenols were catalytically cleaved with hydrogen gas using a rhodium catalyst and phosphinite directing groups (DGs). Despite this promising initial result, ortho substituents in the 2,2′-biphenol substrates were required for this transformation, and our general understanding of activating unstrained aryl–aryl bonds is still limited. A number of questions remain to be addressed. For example, can other types of DGs, besides those strongly coordinative phosphorus-based ones, be used in the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond activation? Can other TMs besides expensive rhodium be employed as the catalyst? Can other reagents besides hydrogen gas react with the C–C cleavage intermediate? How does a metal catalyst approach the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond to be cleaved? Answers to these questions could be important for expanding the substrate scope and reaction varieties of this transformation. In this Article, we describe a detailed development of a ruthenium-catalyzed reductive cleavage of unstrained C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds and the mechanistic study of this reaction (Scheme 2C). Nitrogen-based heterocycles were found to be excellent DGs, and, besides hydrogen gas, secondary alcohols and silanes could also be employed as the reductant for this transformation.

Scheme 2. Activation of Nonpolar Unstrained C–C Bonds.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Pyridine and related heterocycles have been frequently employed as DGs in catalytic C–H activation reactions.11 They have also been used in C–C activation of ketones.12 Thus, the 2,2′-(3-methylpyrdinyl)-substituted biphenyl (1a) was chosen as the initial substrate. Rhodium-based catalysts were naturally examined first. Using [Rh(C2H4)Cl]2, [Rh-(COD)Cl]2, or Rh(COD)2NTf2 as the catalyst, trace or no desired product was observed (Table 1, entries 1, 2, and 4). However, adding NaI as the additive to the [Rh(COD)Cl]2-catalyzed reaction, 39% yield of the desired C–C cleavage product was obtained (Table 1, entry 3). This result showed the feasibility of using pyridine as DGs for C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond activation, although the exact role of NaI is still unclear. Note that using the pyridine DG, ortho substitution at the 3,3′ positions was not required, which is distinct from the prior 2,2′-biphenol activation.10 This motivated us to test other readily available TM complexes as precatalysts for this transformation. While the Ni(0), Co(0), and Ir(I) complexes gave no desired cleavage product (entries 5–7), Ru(II) dichloride complexes nevertheless exhibited remarkable reactivity (entries 11–16). RuCl3· xH2O showed moderate reactivity (entry 10), but Ru3(CO)1212b and Cp*Ru(COD)Cl were not reactive. Among the various Ru complexes examined, Ru(COD)Cl2 was found to be most efficient (entry 14). Besides 1,4-dioxane, other solvents, such as toluene and THF, were also suitable for this transformation (entries 15 and 16).

Table 1.

Selected Optimization Study for the Hydrogenation Condition

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entrya | conditions | yieldb |

| 1 | 10 mol % [Rh(C2H4)Cl]2 | trace |

| 2 | 10 mol % [Rh(COD)Cl]2 | n.d. |

| 3 | 10 mol % [Rh(COD)Cl]2 + 100 mol % NaI | 39% |

| 4 | 20 mol % Rh(COD)2NTf2 | n.d. |

| 5 | 20 mol % Ni(COD)2 | n.d. |

| 6 | 10 mol % Co2(CO)8 | n.d. |

| 7 | 10 mol % [Ir(COD)Cl]2 | n.d. |

| 8 | 6.7 mol % Ru3(CO)12 | n.d. |

| 9 | 20 mol % Cp*Ru(COD)Cl | n.d. |

| 10c | 20 mol % RuCl3·xH2O | 26% |

| 11 | 10 mol % [Ru(p-cymeme)Cl2]2 | 50% |

| 12 | 10 mol % [Ru(p-cymeme)I2]2 | 66% |

| 13 | 20 mol % Ru(COD)Cl2 | 89% |

| 14 | 10 mol % Ru(COD)Cl2 | 89% (83%) |

| 15 | 10 mol % Ru(COD)Cl2, tol as solvent | 88% |

| 16 | 10 mol % Ru(COD)Cl2, THF as solvent | 77% |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol), 20 mol % monomer or 10 mol % dimer or 6.7 mol % trimer of metal catalyst, 1,4-dioxane (0.075 M), 130 °C, 18 h, Q-tube filled with 150 psi H2 gas.

Unless otherwise noted, the yields were determined by 1H NMR using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as internal standard; n.d. = not detected; the yield in parentheses is isolated yield.

The catalyst loading was based on the formula of RuCl3.

Alternative reductants besides H2 gas were then sought, which, if successful, could provide a more convenient way to operate this C–C cleavage reaction (Table 2). To our delight, a variety of mild reductants were found reactive under this Ru-catalyzed condition, and afforded the desired product. For example, potassium formate salt and Hantzsch ester gave 9% and 58% yields of product 2a, respectively (entries 2 and 3). Diverse secondary alcohols could also serve as a hydride source through a transfer hydrogenation process (entries 4–8). Among all of the alcohols tested, cyclopentanol proved to be most efficient (entry 8), although an excess amount was needed for a higher conversion (entries 9–13). 84% yield was achieved using 50 equiv of cyclopentanol with toluene as solvent. In addition, a combination of silane and water (1:1) was found to be an excellent reductant (entries 14–18).13 An optimal result (85% yield) was obtained when using 5.0 equiv of diphenylmethylsilane with 5.0 equiv of H2O (entry 18).

Table 2.

Screening for Alternative Reductantsa

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entrya | conditions | yieldb |

| 1 | 10 equiv of HCOONH4 | n.d. |

| 2 | 10 equiv of HCOOK | 9% |

| 3 | 10 equiv of Hantzsch ester | 58% |

| 4 | 10 equiv of diphenylmethanol | 20% |

| 5c | 2-propanol | 11% |

| 6c | 2-butanol | 22% |

| 7c | 3-pentanol | 47% |

| 8c | cyclopentanol | 70% |

| 9 | 50 equiv of cyclopentanol | 66% |

| 10 | 30 equiv of cyclopentanol | 62% |

| 11 | 10 equiv of cyclopentanol | 51% |

| 12 | 50 equiv of cyclopentanol, Tol as solvent | 84% (81%) |

| 13 | 50 equiv of cyclopentanol, THF as solvent | 46% |

| 14 | 10 equiv of (TMS)3SiH + 10 equiv of H2O | 12% |

| 15 | 10 equiv of Et3SiH + 10 equiv of H2O | 28% |

| 16 | 10 equiv of PhMe2SiH + 10 equiv of H2O | 42% |

| 17 | 10 equiv of Ph2MeSiH + 10 equiv of H2O | 80% |

| 18 | 5 equiv of Ph2MeSiH + 5 equiv of H2O | 85% (78%) |

Reaction condition: 1a (0.1 mmol), 10 mol % Ru(COD)Cl2, 1,4-dioxane or other solvents (1.0 mL), 130 °C, 24 h, sealed vial.

Unless otherwise noted, the yields were determined by 1H NMR using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as internal standard; n.d. = not detected; the yields in parentheses are isolated yields.

The indicated alcohols were used as solvent.

With three high yielding conditions in hand, the substrate scope was investigated next (Table 3). First, besides 3-methylpyridine, simple pyridine can also serve as an effective DG (entry 2). Substitutions on the arene at 3, 4, or 5 positions were all tolerated (entries 3–6), and the yield was lower for the 3,3′-disubstituted substrates likely due to the steric hindrance (2c). In addition, phenyl and furyl-substituted substrates (2g and 2h) showed good reactivity. A range of functionalization groups, such as fluoride (2i), chloride (2j and 2p), bromide (2k), trifluoromethyl (2l), OCF3 (2m), ester (2n), amide (2o), OMe (2q), and silyl ether (2r), were found compatible. Interestingly, when a fluorine substituent is ortho to the DG (entry 20), partial C–F bond activation/cleavage product was obtained;14 for comparison, fluorine substitutions at other positions (2i and 2w) were intact. When a ketone moiety was present (entry 21), partial reduction to the corresponding alcohol was observed, particularly under the transfer hydrogenation conditions. Unsurprisingly, alcohol moieties (2u) were tolerated. The bulkier binaphthyl-derived substrate was not reactive, likely due to the steric hindrance around of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond (entry 23). Regarding the scope of DGs, substituted pyridines with various electronic properties exhibited similar reactivity (entries 24–26). Gratifyingly, other heteroarenes, including pyrimidine (entry 27), five-membered pyrazole (entry 28), and quinoline (entry 29), were found as competent DGs. More labile oxazoline (1ac), oxazole (1ad), and nitrile (1ae) were ineffective. Finally, attempts to cleave an aryl–pyridyl bond or use a monobidentate DG were unfruitful at this stage (entries 33 and 34).

Table 3.

Substrate Scopea

|

Condition 1: biaryl 1 (0.1–0.2 mmol), Ru(COD)Cl2 (10 mol %), 1,4-dioxane (0.075 M), 130 °C, 18 h, Q-tube filled with 150 psi H2 gas. Condition 2: biaryl 1 (0.1–0.2 mmol), Ru(COD)Cl2 (10 mol %), 5.0 equiv of Ph2MeSiH, 5.0 equiv of H2O, 1,4-dioxane (1.0 mL/0.1 mmol 1), 130 °C, 24 h, sealed vial. Condition 3: biaryl 1 (0.1–0.2 mmol), Ru(COD)Cl2 (10 mol %), 50 equiv of cyclopentanol, toluene (1.0 mL/0.1 mmol 1), 130 °C, 24 h, sealed vial. All yields are isolation yields.

Reaction time was 6 h.

Reaction time was 3 h.

Reaction time was 11 h.

The total yields are isolation yields, and the ratio of the two products was determined by 1H NMR.

The two products were both observed and isolated from the reaction system.

Ru(COD)Cl2 (20 mol %), 160 °C.

Ru(COD)Cl2 (20 mol %), 150 °C.

(EtO)3SiH (5.0 equiv) was used instead of Ph2MeSiH. n.d. = not detected.

The limits of the catalyst loading and reaction temperature under the hydrogenation condition were further investigated (Table 4). Reducing the Ru loading from 10 to 2.5 mol % only marginally affected the yield (entry 1, Table 4); further lowering the catalyst loading to 1 mol % still afforded 55% yield of the product (entry 2, Table 4). It was surprising that, at a lower temperature (110 °C), a higher yield (90%) was obtained (entry 4, Table 4). Further decreasing the temperature to 70 °C still showed moderate reactivity (entries 5 and 6, Table 4). The hydrogen pressure could be further reduced to 70 psi without affecting the reaction efficiency (entries 7 and 8, Table 4). A lower yield (65%) was obtained when 30 psi of hydrogen was used (entry 9, Table 4).

Table 4.

Exploring the Limits of Hydrogenolysis of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) Bonds

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entrya | X (mol %) | T (°C) | Y (psi) | yieldb |

| 1c | 2.5 | 130 | 150 | 80% |

| 2d | 1.0 | 130 | 150 | 55% |

| 3e | 10 | 130 | 150 | 83% |

| 4 | 10 | 110 | 150 | 90% |

| 5 | 10 | 90 | 150 | 59% |

| 6 | 10 | 70 | 150 | 33% |

| 7 | 10 | 130 | 110 | 90% |

| 8 | 10 | 130 | 70 | 89% |

| 9 | 10 | 130 | 30 | 65% |

Conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol), Ru(COD)Cl2, 1,4-dioxane (C cat = 0.0075 M), 18 h, Q-tube filled with H2 gas.

Isolated yield.

0.4 mmol of 1a was used.

1.0 mmol of 1a was used.

0.1 mmol of 1a was used.

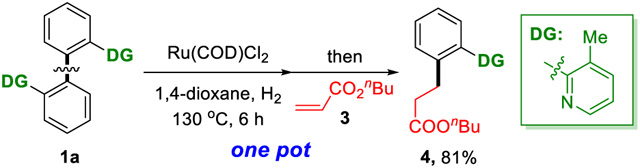

In addition, a one-pot C–C activation/C–C formation approach has also been established (eq 1). After the hydrogenolysis of the aryl–aryl bond, the ruthenium catalyst was found to remain active. Subsequent addition of acrylate allowed for mono ortho alkylation of the C–C cleavage product in a high yield.15 This result shows the potential to couple aryl–aryl bond activation with subsequent functionalization using a single catalyst.

|

(1) |

MECHANISTIC STUDIES

The mechanism of the Ru-catalyzed aryl–aryl bond activation was explored using a combination of computational and experimental efforts. Three possible reaction pathways are proposed (Figure 1). Path a involves insertion of a Ru(II) dichloride species (“RuCl2”) into the aryl–aryl bond to give a Ru(IV) intermediate, which then undergoes hydrogenolysis to give the monomer product. Path b is initiated by a Ru(II) monohydride monochloride species (“RuHCl”), generated via monohydrogenation of the ruthenium dichloride precursor.16 Oxidative addition of the “RuHCl” into the aryl–aryl bond followed by C–H reductive elimination affords one monomer product, and the resulting ruthenium aryl intermediate then reacts with H2 to deliver the other monomer product and regenerate the “RuHCl” catalyst. Path c is based on a Ru(II) dihydride (“RuH2”) species, generated from double hydrogenation of the “RuCl2” precursor.17 Similarly, insertion of the “RuH2” intermediate into the aryl–aryl bond, followed by double C–H reductive elimination, should afford two monomer products. The resulting Ru(0) can then react with H2 to regenerate the “RuH2” species (for a discussion of an alternative Ru(0)-initiated pathway, see the Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Proposed possible reaction pathways.

DFT Calculation.

To differentiate the three possible pathways, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed. It was found that the “RuHCl” pathway (path b) was the most favorable. The computed energy profile in Figure 2 shows that “RuHCl” complex 5b is the active catalyst species in the catalytic cycle, which is formed from the endothermic reaction of RuCl2 species 5a with H2 via TS1 with a barrier of 21.3 kcal/mol. In both 5a and 5b, the two pyridine DGs adopt a trans geometry. This places the target aryl–aryl bond in closer proximity to the Ru, which is evidenced by the short Ru···C distances of 2.3–2.6 Å in 5a and 5b (vide infra, Figure 5, the X-ray structure of 5ah). This agostic C–C/Ru coordination leads to a low barrier of 12.2 kcal/mol for the subsequent C(aryl)–C(aryl) oxidative addition transition state TS2b with respect to 5b. The overall activation free energy of TS2b is 24.5 kcal/mol with respect to the resting state 5a. In contrast, the experimentally observed low reactivity of biaryl substrates with only one pyridine substituent (e.g., 1af) can be attributed to the lack of the agostic C–C coordination with the Ru (see Figure S7.2.2 for detailed computational results). The necessity of two DGs for the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond cleavage has also been demonstrated in the catalytic activation of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds of 2,2′-biphenols by installing phosphinites as DGs in our prior study.10 After the C–C cleavage step, the ensuing C–H reductive elimination (TS3) and σ-bond metathesis with H2 (TS4) both occur with low barriers, leading to two monomer products (2a) and regenerating the “RuHCl” catalyst (5b).

Figure 2.

DFT-computed reaction energy profile of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond activation of substrate 1a catalyzed by a Ru monohydride monochloride catalyst (path b).

Figure 5.

Capture of the resting state of the catalyst.

The possibility of the “RuCl2” and “RuH2” pathways is also considered, and the key results are summarized in Figure 3. In the “RuCl2” pathway (path a, Figure 3A), although the oxidative addition of C(aryl)–C(aryl) (TS2a) requires a relatively low barrier of 20.8 kcal/mol with respect to the “RuCl2” species 5a, the resulting octahedral Ru intermediate 6a is coordinatively saturated and thus incapable of binding with H2 and undergoing hydrogenolysis of the Ru–C(aryl) bonds. The transition state TS5 for H2 cleavage has a barrier of 28.6 kcal/mol, even higher than that of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) cleavage (TS2b) in the “RuHCl” pathways (Figure 2). Our calculations indicated several other possible pathways of 6a reacting with H2, including the one via dissociation of one of the pyridine DGs or one chloride ligand,18 all require high barriers (see details in Figure S7.2.3). Figure 3B shows that the formation of the RuH2 complex 5c from 5a is endergonic by 34.8 kcal/mol. This results in a highly disfavored C(aryl)–C(aryl) oxidative addition transition state TS2c (ΔG‡ = 53.0 kcal/mol with respect to 5a) via the ruthenium dihydride complex (see details in Figure S7.2.4). Taken together, these computational results indicate that the “RuCl2” and “RuH2” pathways are both dis-favored. In addition, our DFT calculations show that, although the reductive elimination of RuH2 (5c) to form a Ru(0) species is energetically feasible, the Ru(0) pathway requires very high activation barriers for the C(aryl)–C(aryl) oxidative addition and the further hydrogenolysis steps (see details in Figure S7.2.5). Therefore, the DFT calculations suggested the “RuHCl” pathway (path b, Figure 1) is the most feasible.

Figure 3.

DFT computed pathways for the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond activation of substrate 1a catalyzed by Ru dichloride and Ru dihydride catalysts. Gibbs free energies and enthalpies (in parentheses) are in kcal/mol with respect to the RuCl2 complex 5a.

Kinetic Studies.

To validate the computational results that favor the “RuHCl”-mediated C–C activation pathway, the following kinetic studies were performed. First, the fate of 1,5-cyclooctadiene (COD) on the Ru precatalyst was determined. It was found that the COD ligand was hydrogenated to cyclooctene and cyclooctane in high efficiency at the beginning of the reaction (Scheme 3, eq 2). This result indicated that COD is likely not involved in the catalytic cycle. Second, the kinetic profile of the reaction with substrate 1a was measured. The initial-rate method was employed to determine the reaction order of each component. The reaction was found to exhibit first-order dependence on the concentration of Ru(COD)Cl2, zero-order on [substrate 1a] and [COD], and pseudo zero-order on [H2] under a higher pressure, but some rate dependence on [H2] was observed under a relatively low H2 gas pressure (<40 psi) (Scheme 3, eq 3, and see Table S5.2.3 for details).19 These kinetic data are consistent with the DFT calculation (vide supra, Figure 2), which suggests that the oxidative addition step is the turnover-limiting step (TLS).

Scheme 3. Kinetic Studies with the Model Substrate.

In addition, Hammett plot analysis was conducted to investigate the sensitivity of the reaction to electronic changes (Figure 4).20 The results indicated that the electron-withdrawing substituents on the arenes could promote the reaction to some extent, while electron-donating groups slowed the reaction. This observation is also consistent with the DFT calculated results, in which the oxidative addition step is predicted to be the TLS, as the electron-deficient bonds typically promote oxidative addition.

Figure 4.

Hammett plot.

Resting State.

Considerable endeavors have been made to capture the DFT calculated resting state, “RuCl2” species 5a. After numerous attempts, heating a mixture of substrate 1ah and 30 mol % of Ru(COD)Cl2 under 150 psi H2 atmosphere in 1,4-dioxane at 130 °C for 20 min afforded a dark green metal complex (5ah). The structure of complex 5ah was unambiguously determined by X-ray crystallography (Figure 5), which is consistent with the proposed “RuCl2” resting state by DFT (vide supra, Figure 2). In complex 5ah, the metal center exhibits octahedral geometry with the two pyridine DGs adopting a trans spatial relationship. An interesting η4-coordination mode between two arene π bonds and the Ru center was observed;21 in particular, the bond lengths between the Ru center and the carbons to be cleaved are short: ca. 2.2 Å. Thus, this structure shows that the Ru(II) center is very close to the target C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond. As compared to d8 Rh(I) that favors a square planar geometry, the d6 Ru(II) can easily form a 18 electron complex through coordination with two arene π bonds. The agostic interaction with the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond, as illustrated in the structure of 5ah, is anticipated to be important for the desired C–C bond activation.

In addition, the reaction of substrate 1ah was monitored by 1H NMR, in which the “RuCl2” species 5ah was observable from the very beginning to almost the end of the reaction by comparing the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude mixture with that of the isolated 5ah (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Monitoring the reaction of substrate 1ah.

Moreover, complex 5ah is catalytically active. When 10 mol % of the 5ah was employed as the catalyst under otherwise identical conditions, 91% yield of the desired product was obtained (eq 4). Therefore, all of the above observations are consistent with the proposal of having the “RuCl2” species (5a) as the resting state of the catalyst.

|

(4) |

Other Control Experiments.

To explore the “RuHCl”-mediated reaction pathway, a ruthenium monohydride monochloride complex 17 was synthesized and subjected to the reaction with substrate 1a in the absence of hydrogen gas (Scheme 4, eq 5).22 To our delight, 60% yield of the desired monomer product was obtained on the basis of the hydride complex.23 For comparison, the analogous ruthenium dihydride complex 1824 gave only trace product via LC–MS analysis under the same reaction conditions (Scheme 4, eq 6). These results suggest the important role of the chloride ligand in the Ru-catalyzed C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond activation.

Scheme 4. Further Control Experiments.

To further examine the possibility of the Ru(0)-initiated pathway, a control experiment was run with 60 mol % of Mn added to the reaction, as Mn metal is known to be capable of reducing Ru(II) to Ru(0) (Scheme 4, eq 7).25 To our surprise, the reaction with Mn not only gave a lower overall yield on the C–C cleavage products, but also generated a significant amount of arene hydrogenation product 2a′. It is intriguing that the neutral benzene ring is selectively reduced instead of the more electron-deficient pyridine ring, implying a possible directed hydrogenation by a Ru(0) catalyst.26 For comparison, such an over-reduction product was almost not observed under the standard reaction conditions. This experiment suggests that the Ru(0) is unlikely to be the actual catalyst for the activation of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds.

CONCLUSION

In summary, to explore a fundamental reaction mode, we have conducted a detailed study of an unusual Ru-catalyzed activation of unstrained C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds. The reaction limits and substrate scopes have been carefully examined. Besides hydrogen gas, a number of other reagents, such as Hantzsch ester, silanes, and alcohols, have also been found effective to serve as terminal reductants for the reductive cleavage. Various heterocycles, such as pyridine, quinoline, pyrimidine, and pyrazole, can be employed as DGs. In addition, a range of functional groups are compatible under the reaction conditions. Moreover, a one-pot C–C activation/C–C coupling has been realized. Finally, the reaction mechanism has been investigated through collaborative efforts between DFT calculations and experiments. The involvement of a ruthenium(II) monohydride-mediated C(aryl)–C(aryl) activation and a η4-coordinated ruthenium(II) complex as the resting state should have broad implications beyond this work. The knowledge obtained in this study may improve our understanding on activating strong, nonpolar, and unstrained chemical bonds. Efforts on expanding the reaction mode to nonreductive processes are ongoing in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NIGMS (1R01GM124414-01A1) (G.D.) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1654122) (P.L.) are acknowledged for research support. G.L. thanks Shandong University for financial support. Dr. Ki-Young Yoon and Dr. Alexander Filatov are acknowledged for X-ray crystallography. Dr. Jianchun Wang is thanked for helpful discussions. Calculations were performed at the Center for Research Computing at the University of Pittsburgh and the Ex-treme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) supported by the NSF.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b11605.

Text, figures, and tables giving experimental procedures, kinetics data, and crystallographic information; as well as computational details, additional computational results, and Cartesian coordinates (PDF)

X-ray crystallographic data for 5ah (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Murakami M; Ito Y Cleavage of Carbon–Carbon Single Bonds by Transition Metals. Top. Organomet. Chem 1999, 3, 97. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong G, Ed. C–C Bond Activation Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: New York, 2014; Vol. 346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Murakami M, Ed. Cleavage of Carbon–Carbon Single Bonds by Transition Metals; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]; (d) Perthuisot C; Edelbach BL; Zubris DL; Simhai N; Iverson CN; Müller C; Satoh T; Jones WD Cleavage of the carbon–carbon bond in biphenylene using transition metals. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem 2002, 189, 157–168. [Google Scholar]; (e) Ruhland K Transition-Metal-Mediated Cleavage and Activation of C–C Single Bonds. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2012, 2012, 2683–2706. [Google Scholar]

- (2).For recent reviews on “cut and sew” chemistry review, see:; (a) Chen P.-h.; Dong G Cyclobutenones and Benzocyclobutenones: Versatile Synthons in Organic Synthesis. Chem. - Eur. J 2016, 22, 18290–18315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen P.-h.; Billett BA; Tsukamoto T; Dong G Cut and Sew” Transformations via Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carbon–Carbon Bond Activation. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1340–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).For recent reviews on activation of three-membered and four-membered rings, see:; (a) Seiser T; Saget T; Tran DN; Cramer N Cyclobutanes in Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 7740–7752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mack DJ; Njardarson JT Recent Advances in the Metal-Catalyzed Ring Expansions of Three- and Four-Membered Rings. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 272–286. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fumagalli G; Stanton S; Bower JF Recent Methodologies That Exploit C–C Single-Bond Cleavage of Strained Ring Systems by Transition Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 9404–9432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) For a recent book and review on C–CN bond activation, see: Nakao Y Catalytic C–CN Bond Activation In C–C Bond Activation; Dong G, Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp 33–58. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wen Q; Lu P; Wang Y Recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed C–CN bond activations. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 47806–47826. [Google Scholar]

- (5).For recent reviews on less strained C–C activation, see:; (a) Rybtchinski B; Milstein D Metal Insertion into C-C Bonds in Solution. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1999, 38, 870–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) van der Boom ME; Milstein D Cyclometalated Phosphine-Based Pincer Complexes: Mechanistic Insight in Catalysis, Coordination, and Bond Activation. Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 1759–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jun C-H Transition metal-catalyzed carbon–carbon bond activation. Chem. Soc. Rev 2004, 33, 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Park YJ; Park J-W; Jun C-H Metal-Organic Cooperative Catalysis in C-H and C-C Bond Activation and Its Concurrent Recovery. Acc. Chem. Res 2008, 41, 222–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen F; Wang T; Jiao N Recent Advances in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Functionalization of Unstrained Carbon–Carbon Bonds. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 8613–8661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kim D-S; Park W-J; Jun C-H Metal–Organic Cooperative Catalysis in C–H and C–C Bond Activation. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 8977–9015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Gozin M; Weisman A; Ben-David Y; Milstein D Activation of a carbon–carbon bond in solution by transition-metal insertion. Nature 1993, 364, 699–701. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gozin M; Aizenberg M; Liou S-Y; Weisman A; Ben-David Y; Milstein D Transfer of methylene groups promoted by metal complexation. Nature 1994, 370, 42–44. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liou S-Y; Gozin M; Milstein D Directly Observed Oxidative Addition of a Strong Carbon-Carbon Bond to a Soluble Metal Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 9774–9775. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Liou S-Y; E. van der Boom M; Milstein D Catalytic selective cleavage of a strong C–C single bond by rhodium in solution. Chem. Commun 1998, 687–688. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Onodera S; Ishikawa S; Kochi T; Kakiuchi F Direct Alkenylation of Allylbenzenes via Chelation-Assisted C–C Bond Cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9788–9792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ruhland K; Obenhuber A; Hoffmann SD Cleavage of Unstrained C(sp2)—C(sp2) Single Bonds with Ni0 Complexes Using Chelating Assistance. Organometallics 2008, 27, 3482–3495. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhu J; Wang J; Dong G Catalytic activation of unstrained C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds in 2,2’-biphenols. Nat. Chem 2019, 11, 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).For recent reviews on directed C–H activation, see:; (a) Chen X; Engle KM; Wang D-H; Yu J-Q Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C-H Activation/C-C Cross-Coupling Reactions: Versatility and Practicality. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 5094–5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Colby DA; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Rhodium-Catalyzed C-C Bond Formation via Heteroatom-Directed C-H Bond Activation. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 624–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lyons TW; Sanford MS Palladium-Catalyzed Ligand-Directed C-H Functionalization Reactions. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 1147–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang M; Zhang Y; Jie X; Zhao H; Li G; Su W Recent advances in directed C–H functionalizations using monodentate nitrogen-based directing groups. Org. Chem. Front 2014, 1, 843–895. [Google Scholar]; (e) Daugulis O; Roane J; Tran LD Bidentate, Monoanionic Auxiliary-Directed Functionalization of Carbon–Hydrogen Bonds. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 1053–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).For C–C activation directed by pyridine and other heterocycles, see:; (a) Suggs JW; Jun CH Directed cleavage of carbon-carbon bonds by transition metals: the α-bonds of ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1984, 106, 3054–3056. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chatani N; Ie Y; Kakiuchi F; Murai S Ru3(CO)12-Catalyzed Decarbonylative Cleavage of a C-C Bond of Alkyl Phenyl Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 8645–8646. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jun C-H; Lee H Catalytic Carbon-Carbon Bond Activation of Unstrained Ketone by Soluble Transition-Metal Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 880–881. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jun C-H; Lee D-Y; Kim Y-H; Lee H Catalytic Carbon-Carbon Bond Activation of sec-Alcohols by a Rhodium(I) Complex. Organometallics 2001, 20, 2928–2931. [Google Scholar]; (e) Jun C-H; Lee H; Lim S-G The C-C Bond Activation and Skeletal Rearrangement of Cycloalkanone Imine by Rh(I) Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 751–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Jun C-H; Moon CW; Lee H; Lee D-Y Chelation-assisted carbon–carbon bond activation by Rh(I) catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem 2002, 189, 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Li H; Li Y; Zhang X-S; Chen K; Wang X; Shi Z-J Pyridinyl Directed Alkenylation with Olefins via Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–C Bond Cleavage of Secondary Arylmethanols. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 15244–15247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Chen K; Li H; Li Y; Zhang X-S; Lei Z-Q; Shi Z-J Direct oxidative arylation via rhodium-catalyzed C–C bond cleavage of secondary alcohols with arylsilanes. Chem. Sci 2012, 3, 1645–1649. [Google Scholar]; (i) Lei Z-Q; Li H; Li Y; Zhang X-S; Chen K; Wang X; Sun J; Shi Z-J Extrusion of CO from Aryl Ketones: Rhodium(I)-Catalyzed C-C Bond Cleavage Directed by a Pyridine Group. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 2690–2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Ko HM; Dong G Cooperative activation of cyclobutanones and olefins leads to bridged ring systems by a catalytic [4 + 2] coupling. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Xia Y; Lu G; Liu P; Dong G Catalytic activation of carbon–carbon bonds in cyclopentanones. Nature 2016, 539, 546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Xia Y; Wang J; Dong G Distal-Bond-Selective C-C Activation of Ring-Fused Cyclopentanones: An Efficient Access to Spiroindanones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 2376–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Xia Y; Wang J; Dong G Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling of Simple Ketones via Activation of Unstrained Carbon–Carbon Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 5347–5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Zhao T-T; Xu W-H; Zheng Z-J; Xu P-F; Wei H Directed Decarbonylation of Unstrained Aryl Ketones via Nickel-Catalyzed C—C Bond Cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Rendler S; Oestreich M Hypervalent Silicon as a Reactive Site in Selective Bond-Forming Processes. Synthesis 2005, 2005, 1727–1747. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jia Z; Liu M; Li X; Chan ASC; Li C-J Highly Efficient Reduction of Aldehydes with Silanes in Water Catalyzed by Silver. Synlett 2013, 24, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yan M; Jin T; Chen Q; Ho HE; Fujita T; Chen L-Y; Bao M; Chen M-W; Asao N; Yamamoto Y Unsupported Nanoporous Gold Catalyst for Highly Selective Hydrogenation of Quinolines. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 1484–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Yutaka I; Naoto C; Shuhei Y; Shinji M Rhodium-Catalyzed Si-F Exchange Reaction between Fluorobenzenes and a Disilane. Catalytic Reaction Involving Cleavage of C-F Bonds. Chem. Lett 1998, 27, 157–158. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tobisu M; Xu T; Shimasaki T; Chatani N Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction of Aryl Fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 19505–19511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ahrens T; Kohlmann J; Ahrens M; Braun T Functionalization of Fluorinated Molecules by Transition-Metal-Mediated C–F Bond Activation To Access Fluorinated Building Blocks. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 931–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).For selected Ru-catalyzed C–H acrylate coupling, see: Arockiam, P. B.; Bruneau, C.; Dixneuf, P. H. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Activation and Functionalization. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 5879–5918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jung S; Ilg K; Brandt CD; Wolf J; Werner H A series of ruthenium(ii) complexes containing the bulky, functionalized trialkylphosphines tBu2PCH2XC6H5 as ligands. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 2002, 318–327. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuznetsov VF; Abdur-Rashid K; Lough AJ; Gusev DG Carbene vs Olefin Products of C-H Activation on Ruthenium via Competing α- and β-H Elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 14388–14396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Morilla ME; Rodríguez P; Belderrain TR; Graiff C; Tiripicchio A; Nicasio MC; Pérez PJ Synthesis, Characterization, and Reactivity of Ruthenium Diene/Diamine Complexes Including Catalytic Hydrogenation of Ketones. Inorg. Chem 2007, 46, 9405–9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Nolan SP; Belderrain TR; Grubbs RH Convenient Synthesis of Ruthenium(II) Dihydride Phosphine Complexes Ru-(H)2(PP)2 and Ru(H)2(PR3)x (x = 3 and 4). Organometallics 1997, 16, 5569–5571. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen J; Stevens ED; Nolan SP Synthesis and Reactivity of the Ruthenium(II) Dihydride Ru-(Ph2PNMeNMePPh2)2H2. Organometallics 1998, 17, 3875–3882. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lu Y; Liu Z; Guo J; Qu S; Zhao R; Wang Z-X A DFT study unveils the secret of how H2 is activated in the N-formylation of amines with CO2 and H2 catalyzed by Ru(ii) pincer complexes in the absence of exogenous additives. Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 12148–12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).We reasoned that under a low H2 pressure the concentration of the “RuHCl” species (5b) is in equilibrium with the resting state (5a), thus showing rate dependence with the H2 pressure. In contrast, under a high H2 pressure, a situation of “saturation kinetics” could take place; therefore, the initial rate is less dependent on the [H2].

- (20).Stowers KJ; Sanford MS Mechanistic Comparison between Pd-Catalyzed Ligand-Directed C-H Chlorination and C-H Acetoxylation. Org. Lett 2009, 11, 4584–4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).A structurally related Ru(II) biaryl bispyridyl complex with a η4-coordination was reported by Ryabov and Lagadec through a biaryl coupling reaction, see:; Saavedra-Díaz O; Cerón-Camacho R; Hernández S; Ryabov AD; Le Lagadec R Denial of Tris(C, N-cyclometalated) Ruthenacycle: Nine-Membered η6-N, N-trans or η2-N, N-cis RuII Chelates of 2,2′-Bis(2-pyridinyl)-1,1′-biphenyl. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2008, 2008, 4866–4869. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Solari E; Gauthier S; Scopelliti R; Severin K Multifaceted Chemistry of [(Cymene)RuCl2]2 and PCy3. Organometallics 2009, 28, 4519–4526. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Complex 17 can promote hydrogen transfer from 1,4-dioxane. For details, see the Supporting Information.

- (24).Demerseman B; Mbaye MD; Sémeril D; Toupet L; Bruneau C; Dixneuf PH Direct Preparation of [Ru(η2-O2CO)(η6-arene)(L)] Carbonate Complexes (L = Phosphane, Carbene) and Their Use as Precursors of [RuH2(p-cymene)(PCy3)] and [Ru(η6-arene)(L)(MeCN)2][BF4]2: X-ray Crystal Structure Determination of [Ru(η2-O2CO)(p-cymene)(PCy3)]·1/2CH2Cl2 and [Ru(η2-O2CO)-(η6-C6Me6)(PMe3)]·H2O. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2006, 2006, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar]

- (25).McKinney RJ; Colton MC Homogeneous ruthenium-catalyzed acrylate dimerization. Isolation, characterization and crystal structure of the catalytic precursor bis(dimethyl muconate)(trimethyl phosphite)ruthenium(0). Organometallics 1986, 5, 1080–1085. [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) Prechtl MHG; Scariot M; Scholten JD; Machado G; Teixeira SR; Dupont J Nanoscale Ru(0) Particles: Arene Hydrogenation Catalysts in Imidazolium Ionic Liquids. Inorg. Chem 2008, 47, 8995–9001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Touge T; Arai T Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unprotected Indoles Catalyzed by η6-Arene/N-Me-sulfonyldiamine–Ru(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 11299–11305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rakers L; Martínez-Prieto LM; López-Vinasco AM; Philippot K; van Leeuwen PWNM; Chaudret B; Glorius F Ruthenium nanoparticles ligated by cholesterol-derived NHCs and their application in the hydrogenation of arenes. Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 7070–7073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.