Abstract

Though the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBTI) is well-established, the paucity of credentialed providers hinders widespread access. Further, the impact of alternatives such as web-delivered CBTI has not been adequately tested on common insomnia comorbidities such as anxiety. Therefore, we assessed the impact of an empirically validated web-delivered CBTI intervention on insomnia and comorbid anxiety symptoms. A sample of 22 adults (49.8±13.5 yo; 62.5% female) with DSM-5 based insomnia were randomized to either an active CBTI treatment group (n = 13) or an information-control (IC) group (n = 9). Participants in the CBTI group underwent a standard CBTI program delivered online by a ‘virtual’ therapist, whereas the IC group received weekly ‘sleep tips’ and general sleep hygiene education via electronic mail. All participants self-reported sleep parameters, including sleep onset latency (SOL), insomnia symptoms per the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and anxiety symptoms per the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) at both baseline as well as follow- up assessment one week post-treatment. There were no significant differences between the CBTI and IC groups on baseline measures. The CBTI group showed significantly larger reductions in BAI scores (t = 2.6; p < .05; Cohen’s d = .8) and ISI scores (t = 2.1; p < .05; Cohen’s d = .9) at follow-up than did the IC group. Further, changes in SOL from baseline (62.3±44.0 minutes) to follow-up (22.3±14.4 minutes) in the CBTI group were also significantly greater (t = 2.3; p < .05; Cohen’s d = .9) than in the IC group (baseline: 55.0±44.2 minutes; follow-up: 50.±60.2 minutes).

This study offers preliminary evidence that a web-delivered CBTI protocol with minimal patient contact can improve comorbid anxiety symptoms among individuals with insomnia.

Keywords: Anxiety, Insomnia, CBTI, Randomized Clinical Trial

INTRODUCTION

The historical view of insomnia as a symptom or ‘secondary’ consequence of an underlying condition arguably stems from its pervasiveness across the entire spectrum of medical and psychiatric disorders [1]. Indeed, insomnia co-occurring with another disorder is the most prevalent insomnia phenotype, accounting for over 80% of all cases [2]. However, epidemiological studies suggest that insomnia may not only precede the so-called primary condition but also exacerbate its course and severity [3-5]. Further, treatment studies show that insomnia often fails to remit despite successful alleviation of the primary disorder [6-8]. These observations have led to a more empirically robust conceptualization of insomnia as a primary disorder which can strongly influence its comorbidities [9]. As reflected in the 2005 NIH state-of-the-science conference statement, there is now growing evidence that treating insomnia can lead to improvements in a variety of comorbid conditions [10]. Cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBTI), now recognized as a first-line treatment for insomnia [11, 12], has been shown to improve comorbid depression, chronic pain, and immune function (see Smith et al., [13] for a review). A small but emerging literature also offers preliminary support for the efficacy of CBTI in ameliorating anxiety symptoms.

Though estimates vary as a function of diagnostic and methodological rigor, the comorbidity between insomnia and clinical anxiety is significant; some studies suggest that over 70% of patients with anxiety disorders also experience insomnia [14, 15]. Further, in a well-controlled recent study, participants with an insomnia diagnosis were 17 times more likely to report anxiety than were normal sleepers [16]. Insomnia is also a particularly refractory clinical feature of many anxiety disorders. In a clinical trial of cognitive behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), nearly 50% of participants continued to report residual insomnia even though they no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD [8]. Not surprisingly, per a meta-analysis of CBTI clinical trials that included an anxiety outcome measure, insomnia treatment was associated with a moderate improvement in concurrent anxiety symptoms [17].

Despite these established benefits of CBTI for insomnia and concomitant anxiety, a number of practical barriers hinder widespread access to CBTI. First, the availability of CBTI is limited due to the severe shortage of credentialed behavioral sleep medicine (BSM) providers. While the prevalence of anxiety disorders and insomnia are each roughly 20% in the U.S. [18, 19], there are presently only a little over 200 board-certified BSM providers [20,21]. This staggering mismatch between supply and demand highlights the need for an alternative to therapist-delivered CBTI. Although CBTI delivered by nurses and para-professionals have shown promise, these modalities also rely on face-to-face contact and thus cannot be scaled to meet the population need [22]. A web- based CBTI protocol can overcome such obstacles to widespread delivery, reduce health-care costs, and help patients avoid the social stigma associated with meeting a therapist. Further, an internet- based intervention can be easily integrated into the ‘stepped care’ model of health care as an intermediary treatment option between sleep hygiene education and individual CBTI with a credentialed BSM provider [23].

The present study examined the effects of an empirically-validated, web-delivered CBTI protocol on insomnia and comorbid anxiety symptoms. Specifically, participants with DSM-5insomnia [24] were randomized to either an active web-delivered CBTI treatment group (n = 13) or an information-control (IC) group (n = 9). Participants in the CBTI group underwent a standard 6-week CBTI program, whereas the IC group received weekly ‘sleep tips’ and general sleep hygiene education. All participants self-reported sleep parameters, including SOL, insomnia symptoms per the ISI [25], daytime sleepiness per the ESS [26], and anxiety symptoms per the BAI [27] at both baselines as well as at a follow-up assessment one week following treatment. We hypothesized that participants in the CBTI group would experience significantly greater improvements in both insomnia and anxiety symptoms than would those in the IC group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

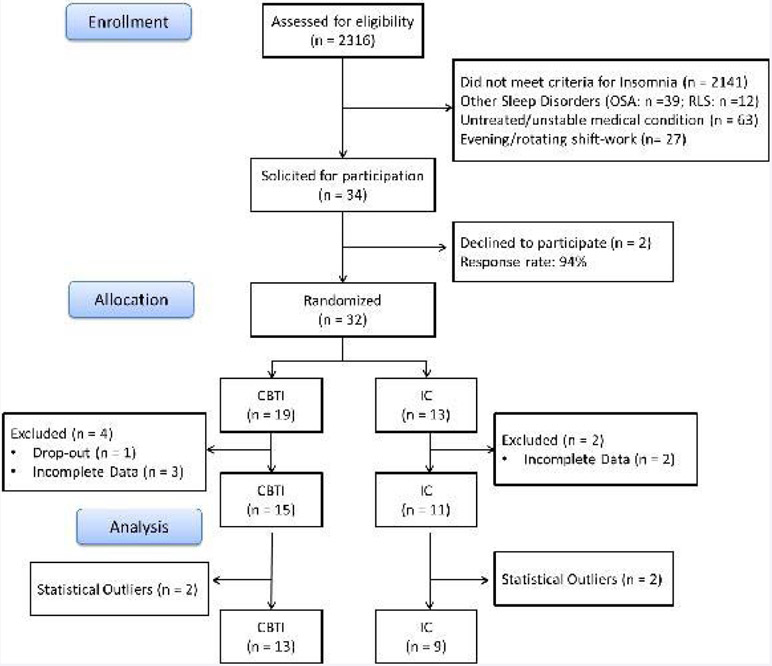

Participants were recruited from the Evolution of pathways to insomnia cohort (EPIC) study, a three-year NIMH-funded prospective investigation of a large community-based sample from southeastern Michigan [3, 28]. Specifically, participants who completed the third wave of data collection for the EPIC study were assessed for eligibility in the present study based on the following inclusion criteria: met diagnostic criteria for DSM-5 based insomnia [24]; no history of other sleep disorders, including obstructive sleep apnea and restless leg syndrome; absence of unstable/untreated chronic health conditions; no night/rotating shift-work. (Figure 1) depicts the flow of participants through the study. Of the eligible participants (n = 34), 2 declined to participate in the present study (Response rate: 94.1%). The remaining sample (n = 32) was randomized to either a CBTI (n = 19) group or an IC (n = 13) group. Five participants provided incomplete data (< 75%) and one dropped-out prematurely (Retention rate: 81.3%).

Figure 1.

Consort chart depicting flow of participants through the study.

Measures

Per DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, participants earned an insomnia diagnosis if they reported experiencing one or more sleep complaints (e.g., ‘have you experienced difficulty falling asleep?’; ‘have you experienced difficulty staying asleep?’) for at least 3 nights a week for a period of three months or longer. Further, they had to endorse daytime impairment or distress as measured by the following question: ‘to what extent do you consider your sleep problems to interfere with your daily functioning?’ Responses were coded on a 4-point Likert type scale ranging from ‘0’ (‘not at all’) to ‘4’ (‘very much’), such that participants who reported a score of ‘2’ (somewhat) or higher received the diagnosis.

At baseline and at a follow-up assessment one week following treatment, participants completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and self-reported sleep parameters, including sleep onset latency (SOL) and total sleep time (TST). The ISI [25] is an empirically validated, 7-item self-report instrument designed to quantify the severity and impact of insomnia symptoms. Specific sleep impairment factors assessed by the ISI include: severity of sleep onset, sleep maintenance, and early morning awakening problems; sleep dissatisfaction; interference of sleep difficulties with daytime functioning; notice ability of sleep problems by others; and distress caused by sleep difficulties. The BAI is a 21-item questionnaire which assesses the severity of common anxiety symptoms on a 4-point Likert type scale, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety [27]. Psychometric validation studies of the BAI report high internal consistency as well as good discriminant validity [29]. The ESS [26] was used to assess levels of daytime sleepiness, with overall scores of 10 or greater indicating excessive or clinically significant sleepiness [30].

Treatment groups

CBTI: Cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia [31] is a structured, multi-model treatment which targets sleep-disruptive behaviors and beliefs. Data from clinical trials show consistently that CBTI is as effective as pharmacological treatment in the short run, and that it is associated with more durable changes in the long run [32]. In the present study, participants received 6 weekly sessions of standard CBTI [33], which covered all behavioral (e.g., sleep restriction, stimulus control) and cognitive (e.g., cognitive re-structuring, paradoxical intention etc.) components, as well as relaxation strategies (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation and autogenic training) and sleep hygiene. Specifically, participants were immersed in a fully automated media-rich web environment, driven dynamically by baseline and progress data. At the start of each session, an animated “virtual therapist” (The Prof) conducted a progress review with the participant, explored diary data submitted during the week, current sleep status and pattern, and progress achieved against goals previously set. Further details of this online intervention as well as illustrative examples are available in a prior report [22].

IC: The IC group received weekly electronically delivered information on the following topics: the basics of endogenous sleep regulation; the impact on sleep of health problems such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension; the effects of stimulants, such as caffeine and nicotine, and other sleep disruptive substances including alcohol; the relationship between sleep, diet, and exercise; tips on creating a sleep-conducive bedroom environment that is dark, quiet, cool, and comfortable. As with the CBTI group, these topics were divided equally across the 6 weekly sessions. Sleep hygiene is neither the primary cause nor therapeutic target in insomnia disorder [34, 35], as good sleepers and insomniacs generally exhibit comparable sleep hygiene [36]. As such, an IC intervention has not been shown to have any independent effects on insomnia [34], and thus serves as an ideal placebo condition.

Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows – Version 19 [37]. The SOL variable revealed significant skewness; outliers (> 3 SDs above the mean) were therefore excluded case wise from all further analyses (n = 4). Univariate between- group comparisons for continuous measures were accomplished via independent samplest-tests. The effect sizes of all statistically significant differences were assessed per Cohen’s d, with d =.2, .5, .8 suggesting small, medium, and large effects respectively [38].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results

Baseline descriptive statistics for all participants stratified by group appear in (Table 1). Consistent with the gender disparity in the prevalence of insomnia [19], women were over- represented in the sample (62.5%). White Americans constituted the largest racial group (50%), with smaller percentages of other races (36.4% African American; 4.5 % Asian; 9.1% Other). However, the small sample size precluded between-group comparisons in terms of gender and racial composition; counts in a number of individual cells (e.g., only one participant identified as ‘Asian’ in the IC group) were too low for valid chi-square analyses. With regard to sleep parameters, SOL and TST for both groups were in the clinically significant range [39] and comparable to those reported in prior insomnia studies [33]. BAI scores suggested mild to moderate anxiety symptoms among both groups [27]. Consistent with the elevated wake-drive observed in insomnia [40], the present sample did not evidence any signs of excessive daytime sleepiness on the ESS despite short habitual sleep durations (< 7 hrs on average). Finally, there were no statistically significant differences between the CBTI and IC groups in age or any of the baseline measures.

Table 1:

Baseline Sample Characteristics (n = 22).

| IC Group | CBTI Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 9) | (n = 13) | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Age | 44.0 | (13.2) | 53.2 | (12.2) | t = 1.7; p = .11 |

| Sleep onset latency (minutes) | 55.0 | (44.2) | 62.3 | (44.0) | t = 0.6; p = .58 |

| Total sleep time (minutes) | 351.1 | (102.1) | 322.5 | (62.7) | t = −1.0; p = .33 |

| ISI Total | 9.6 | (3.3) | 10.5 | (2.7) | t = 0.8; p = .45 |

| ESS Total | 7.3 | (3.5) | 6.9 | (4.1) | t = −0.2; p = .81 |

| BAI Total | 8.7 | (9.4) | 11.1 | (7.9) | t = 0.3; p = .78 |

Abbreviations: IC: Information-Control; CBTI: Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Insomnia; M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; T = Independent Samples T-Test.

Follow-up summary statistics appear in (Table 2). Between-group differences in post- treatment change scores on all study variables across the CBTI and IC groups were evaluated via independent sample t-tests. With respect to sleep parameters, the CBTI group showed a significantly larger decrease (t = 2.3; p < .05; Cohen’s d = 0.9) in SOL from baseline (62.3±44.0 minutes) to follow-up (22.3±14.4 minutes) than the IC group (baseline: 55.0±44.2 minutes; follow-up: 50.6±60.2 minutes). Further, reductions in ISI scores (t = 2.1; p < .05; Cohen’s d = 0.9) were also significantly greater for the CBTI group than for the IC group. Post- treatment changes in TST and ESS scores did not differ significantly between groups. In terms of comorbid anxiety, the CBTI group exhibited a significantly larger decrease (t = 2.6; p < .05) in BAI scores from baseline (11.1±7.9) to follow-up (7.2±5.8) in comparison to the IC group (baseline: 8.7±9.4; follow-up: 8.7±8.8). Not unlike the sleep parameter changes, this effect was also large (Cohen’s d= 0.8).

Table 2:

Follow-up Data (n = 22).

| Follow-up | Change from | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Baseline | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Sleep onset latency (minutes) | ||||

| IC Group | 50.6 | (60.2) | 4.44 | (35.3) |

| CBTI Group | 22.3 | (14.4) | 40.0 | (35.9) |

| t = 2.3; p < .05; d = 0.9 | ||||

| Total sleep time (minutes) | ||||

| IC Group | 403.9 (98.8) | 52.8 | (53.6) | |

| CBTI Group | 398.4 (62.7) | 75.9 | (95.3) | |

| t = 0.8; p = .51 | ||||

| IC Group | 8.4 | (5.1) | 1.11 (5.1) | |

| CBTI Group | 4.8 | (2.7) | 5.8 | (4.3) |

| t = 2.1; p < .05; d = 0.9 | ||||

| ESS Total | ||||

| IC Group | 7.1 | (3.3) | 0.22 (2.2) | |

| CBTI Group | 4.6 | (3.7) | 2.5 | (3.3) |

| t = − 1.8; p = .06 | ||||

| BAI Total | ||||

| IC Group | 8.7 | (8.8) | − 0.1 (3.9) | |

| CBTI Group | 7.2 | (5.8) | 3.8 | (4.7) |

| t = 2.6; p < .05; d = 0.8 | ||||

Abbreviations: IC: Information-Control; CBTI: Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Insomnia; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; T: Independent Samples T-Test; d = Cohen’s d.

Discussion

The present study involved a randomized clinical trial of a web-delivered CBTI protocol among participants with DSM-5 insomnia and comorbid anxiety symptoms. An information-control condition, which involved sleep education and sleep hygiene tips, served as a credible placebo intervention as it mimics the web-based patient contact inherent in the CBTI protocol but is inert with respect to sleep outcomes [34]. Follow-up data collected one week following treatment revealed that CBTI group experienced significantly greater reductions in anxiety symptoms than did the control group. Further, the CBTI group also showed significantly greater improvements in SOL and overall insomnia symptomatology on the ISI in comparison to the control group. Notably, both SOL and self-reported insomnia symptoms in the CBTI group were within normal limits post-treatment, suggesting disorder remission [39]. Importantly, all above effect sizes were large per standardized norms [38]. Finally, as with any CBTI protocol, application of the sleep-restriction module carries the risk of inducing excessive daytime sleepiness [41]. However, there was no indication that the present protocol was hindered by such adverse iatrogenic effects; ESS scores did not change significantly from baseline to follow-up in either group and remained well below the clinical threshold [30].

This study is an important addition to the relatively sparse literature on sleep-focused treatments for anxiety comorbid with insomnia. Though a number of recent clinical trials of web-delivered CBTI have shown moderate efficacy in improving sleep [42], this is the first report on the effects of a highly innovative and entirely web-delivered CBTI intervention [22] on comorbid anxiety symptoms, as assessed by an empirically validated instrument [27]. Future studies with larger samples are needed to replicate these findings, and, more importantly, to elucidate the mechanisms responsible for the observed improvements in concomitant anxiety. While it may be tempting to attribute the aforesaid anxiolytic effects of CBTI to improved sleep, meditational analyses are needed to reliably examine this hypothesis. Indeed, despite consistent support for the reciprocity between impaired sleep and anxiety symptoms [14-16], an empirically robust model of sleep and anxiety regulation has yet to emerge [43].

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Though we believe the above results are quite promising, they must be interpreted with due consideration to some of the methodological limitations of this study. First, anxiety was not the primary outcome measure in the present study, and, as such, we were unable to quantify the proportion of participants who met strict diagnostic criteria for a particular anxiety disorder. Note that this is reflective of a major gap in the CBTI literature at large, as anxiety is rarely the outcome of interest in CBTI trials; of the over 200 reported CBTI studies, only 28 randomized, placebo-controlled trials included an anxiety measure [17]. We are unaware of any clinical trials that specifically examined the efficacy of CBTI in alleviating symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, one of the most prevalent anxiety disorders [44]. Further, only two prior studies [45, 46] have addressed the impact of CBTI on PTSD symptoms. Importantly, however, both studies combined CBTI with imagery-rehearsal therapy [47], a treatment geared toward cognitive restructuring of nightmares, and were thus unable to parse out the effects of pure CBTI.

A second potential limitation in the present study was that baselines levels of anxiety in the present sample were in the mild to moderate range, thus limiting the generalizability of findings. Note, however, that this reflects the strength of these effects as a significant decrease is more difficult to detect when baseline scores are low. Further, we believe that these results are quite valuable as they speak to the feasibility of an internet-based protocol in addressing less severe forms of comorbid anxiety in the insomnia population. Per the stepped care model of healthcare – which is quickly gaining favor in primary care settings where the need and impact of treatment is the greatest [10, 48] – web-delivered CBTI can effectively reduce patient load on credentialed specialists who can then devote themselves to more challenging and severe clinical presentations.

CONCLUSION

This study offers preliminary evidence that a web-delivered CBTI protocol with minimal patient contact can serve as a cost- and time-effective alternative to traditional face-to-face therapy for insomnia and comorbid anxiety symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The parent EPIC study was supported by an NIMH Grant R01 MH082785 to Dr. Christopher L. Drake.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CBTI

Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Insomnia

- SOL

Sleep Onset Latency

- DSM-5

Diagnostic And Statistical Manual For Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The software and web development for this study was supported by Big Health Limited. Drs. Espie and Bostock receive a salary from Big Health Limited and hold shares in the company, but did not have access to the data analyzed in the present study. Dr. Espie has also participated in speaking engagements and has served as a consultant for Boots Pharmaceuticals and Novartis; received free use of actigraphs by Philips Respironics. Dr. Drake has served as consultant for Teva; has received research support from Merck and Teva; and has served on speakers bureaus for Jazz, Purdue, and Teva. Drs. Pillai, Cheng, and Bazan did not indicate any financial conflicts of interests. Mr. Anderson did not indicate any financial conflicts of interests. Dr. Roth has served as consultant for Abbott, Accadia, AstraZeneca, Aventis, AVER, Bayer, BMS, Cypress, Ferrer, Glaxo Smith Kline, Impax, Intec, Jazz, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Neurocrine, Novartis, Proctor and Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Shire, Somaxon, Transcept; has received research support from Cephalon, Merck, and Transcept; and has served on speakers bureau for Purdue.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey AG. Insomnia: symptom or diagnosis? Clinical psychology review. 2001; 21:1037–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohayon MM Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002; 6: 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake CL, Pillai V, Roth T Stress and sleep reactivity: a prospective investigation of the stress-diathesis model of insomnia. Sleep. 2014; 37: 1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989; 262: 1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pigeon WR, Hegel M, Unützer J, Fan MY, Sateia MJ, Lyness JM, Phillips C. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for late-life depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep. 2008; 31: 481–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geoffroy PA, Scott J, Boudebesse C, Lajnef M, Henry C, Leboyer M, et al. Sleep in patients with remitted bipolar disorders: a meta-analysis of actigraphy studies. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2015; 131: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011; 31: 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zayfert C, DeViva JC. Residual insomnia following cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2004; 17: 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stepanski EJ, Rybarczyk B. Emerging research on the treatment and etiology of secondary or comorbid insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2006; 10: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.[No authors listed]. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2005; 22: 1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey AG, Tang NK. Cognitive behaviour therapy for primary insomnia: can we rest yet? Sleep Med Rev. 2003; 7: 237–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ, Alford C, Argyropoulos SV, Baldwin DS, Bateson AN, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2010; 24:1577–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MT, Huang MI, Manber R. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic insomnia occurring within the context of medical and psychiatric disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005; 25: 559–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monti JM, Monti D. Sleep disturbance in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2000; 4: 263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadimitriou GN, Linkowski P. Sleep disturbance in anxiety disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005; 17: 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Reidel BW, Bush AJ. Epidemiology of insomnia, depression, and anxiety. Sleep. 2005; 28: 1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belleville G, Cousineau H, Levrier K, St-Pierre-Delorme MÈ. Meta-analytic review of the impact of cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia on concomitant anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011; 31: 638–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62: 617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, Lakoma MD, Sampson NA, Shahly V, et al. Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biol Psychiatry. 2011; 69: 592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collop N History of sleep medicine. 5th Annual Conference of the Virginia Academy of Sleep Medicine. Richmond, VA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perils ML, Smith MT. How can we make CBT-I and other BSM services widely available? J Clin Sleep Med. 2008; 4: 11–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C, Ong JC, Douglas NJ, Hames P, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep.2012; 35: 769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espie CA.”Stepped care”: a health technology solution for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy as a first line insomnia treatment. Sleep. 2009; 32: 1549–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). Arlington. VA: US: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011; 34: 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991; 14: 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonia, TX: Psychological Corporation.1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pillai V, Roth T, Mullins HM, Drake CL. Moderators and mediators of the relationship between stress and insomnia: stressor chronicity, cognitive intrusion, and coping. Sleep. 2014; 37: 1199–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabacoff RI, Segal DL, Hersen M, Van Hasselt VB. Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory with older adult psychiatric outpatients. J Anxiety Disord.1997; 11:33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johns MW. Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the epworth sleepiness scale: failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J Sleep Res. 2000; 9: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morin CM, Bastien C, Savard J. Current status of cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: Evidence for treatment effectiveness and feasibility. In: Lichstein MLPKL, editor. Treating sleep disorders: Principles and practice of behavioral sleep medicine. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.2003. pp 262–285. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riemann D, Perils ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009; 13: 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, Marsh GR, Quillian RE. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2001; 285:1856–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet. 2012; 379: 1129–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hood HK, Rogojanski J, Moss TG. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014; 16: 321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gellis LA, Lichstein KL. Sleep hygiene practices of good and poor sleepers in the United States: an internet-based study. Behav Ther. 2009; 40: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IBM. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen J A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992; 112: 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drake CL, Vargas I, Roth T, Friedman NP. Quantitative measures of nocturnal insomnia symptoms predict greater deficits across multiple daytime impairment domains. Behav Sleep Med. 2015; 13:73–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pillai V, Roth T, Drake CL.The nature of stable insomnia phenotypes. Sleep. 2015; 38: 127–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kyle SD, Miller CB, Rogers Z, Siriwardena AN, Macmahon KM, Espie CA. Sleep restriction therapy for insomnia is associated with reduced objective total sleep time, increased daytime somnolence, and objectively impaired vigilance: implications for the clinical management of insomnia disorder. Sleep. 2014; 37:229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng SK, Dizon J. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2012; 81: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dolsen MR, Asarnow LD, Harvey AG. Insomnia as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014; 16: 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman MG, Llera SJ, Erickson TM, Przeworski A, Castonguay LG. Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: a review and theoretical synthesis of evidence on nature, etiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013; 9: 275–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Margolies SO, Rybarczyk B, Vrana SR, Leszczyszyn DJ, Lynch J. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for insomnia and nightmares in Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2013; 69: 1026–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ulmer CS, Edinger JD, Calhoun PS. A multi-component cognitive-behavioral intervention for sleep disturbance in veterans with PTSD: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011; 7:57–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krakow B, Zadra A. Clinical management of chronic nightmares: imagery rehearsal therapy. Behav Sleep Med. 2006; 4: 45–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rollman BL, Herbeck Belnap B, Reynolds CF, Schulberg HC, Shear MK. A contemporary protocol to assist primary care physicians in the treatment of panic and generalized anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003; 25: 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]