Abstract

Rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ng) is critically needed to counter widespread antibiotic resistance. Detection of nucleic acids in genotypic AST can be rapid, but it has not been successful for β-lactams (the largest antibiotic class used to treat Ng). Rapid phenotypic AST for Ng is challenged by the pathogen’s slow doubling time and the lack of methods to quickly quantify the pathogen’s response to β-lactams. Here, we asked two questions: (1) Is it possible to use nucleic acid quantification to measure the β-lactam susceptibility phenotype of Ng very rapidly, using antibiotic-exposure times much shorter than the 1- to 2-h doubling time of Ng? (2) Would such short-term antibiotic exposures predict the antibiotic resistance profile of Ng measured by plate growth assays over multiple days? To answer these questions, we devised an innovative approach for performing a rapid phenotypic AST that measures DNA accessibility to exogenous nucleases after exposure to β-lactams (termed nuclease-accessibility AST [nuc-aAST]). We showed that DNA in antibiotic-susceptible cells has increased accessibility upon exposure to β-lactams and that a judiciously chosen surfactant permeabilized the outer membrane and enhanced this effect. We tested penicillin, cefixime, and ceftriaxone and found good agreement between the results of the nuc-aAST after 15–30 min of antibiotic exposure and the results of the gold-standard culture-based AST measured over days. These results provide a new pathway toward developing a critically needed phenotypic AST for Ng and additional global-health threats.

This study presents a new approach for testing antibiotic-susceptibility in the slow-growing human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae, based on measuring accessibility of pathogen nucleic acids to extracellular reagents. Surprisingly, the beta-lactam susceptibility phenotype was revealed with antibiotic exposures shorter than cell division.

Introduction

Gonorrhea, caused by N. gonorrhoeae (Ng), is the second most common notifiable sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States [1] and the third most common STI globally. Gonorrhea affects 86,900,000 people each year worldwide [2]. Untreated Ng infections can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and neonatal blindness [3] and have a significant financial burden on healthcare systems [4]. Antibiotic resistance in Ng emerged quickly and continues to spread unchecked because there is no rapid antibiotic susceptibility test (AST) to guide treatment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that almost half (550,000) of the 1.14 million new Ng infections reported are antibiotic resistant [5]. Lacking a rapid AST, clinicians are limited to making empiric prescriptions as recommended by the CDC [6] or World Health Organization (WHO) [7]. When resistance to a particular antibiotic exceeds 5%, treatment guidelines are updated and the recommended treatment protocol is escalated to the next line of antibiotic [8,9]. As a result, Ng strains continue to evolve resistance, even to the last-line treatment (dual treatment with azithromycin [AZM]/ceftriaxone [CRO]) [10–12]. The global prevalence and spread of resistant Ng infections has led the CDC to place Ng in its highest (“urgent”) category of antimicrobial-resistant pathogen threats [13] and WHO to label Ng as a high-priority pathogen [14]. Despite the threat of untreatable Ng [15] and an international call for rapid diagnostics [16–18], no phenotypic AST currently exists that can be performed rapidly enough for the point of care (POC).

Successful and timely treatment of Ng infections while still considering antibiotic stewardship requires two sequential steps to be performed at the POC. First, an identification (ID) test is run on the patient’s sample (typically urine or swab) to confirm that the patient is infected with Ng. Then, an AST must be run on the sample to determine whether the infecting strain of Ng is susceptible to the available antibiotics, so that the correct treatment can be prescribed. The health crisis associated with antibiotic-resistant infections is internationally recognized [19], and substantial efforts (both academic [20–22] and commercial [23,24]) are making great progress toward shortening the time required to identify Ng infections. However, there is no published path toward development of a rapid phenotypic AST for Ng, especially for β-lactam antibiotics. Thus, even with swift diagnosis of an Ng infection, prescription of the correct antibiotics at the POC will remain bottlenecked by the lack of a rapid AST.

AST methods are either genotypic or phenotypic. Genotypic methods predict resistance by screening for the presence of known resistance genes, whereas phenotypic methods determine susceptibly and resistance by directly measuring an organism’s response to an antibiotic. Rapid genotypic methods exist for select antibiotic classes such as quinolones [25,26], but the diverse mechanisms of resistance present in Ng would require highly multiplexed assays for most other antibiotic classes [27,28], including β-lactams [29,30], which are the largest class of antibiotics for Ng. For example, hundreds of β-lactamase genes are known [31], and new resistance genes continue to emerge, making it challenging to design a comprehensive genotypic AST, even for a single organism. Only phenotypic AST methods provide the ability to directly detect resistance and susceptibility, regardless of the antibiotic’s mechanism of action. The current gold-standard AST for Ng is agar dilution, a phenotypic method that takes many days and is only performed in a small number of reference laboratories [32]. Efforts have been made to shorten the total assay time of culture-based techniques [33–35], but these methods still rely on multiple cell divisions and thus require many hours because of the slow doubling time (1–2 h) of Ng. The doubling time of Ng is impacted by many factors, including pH [36], temperature [37], initial cell concentration, media, and isolate [38]. Although differences in conditions are straightforward to control in experiments with clinical isolates, the effects of variable growth time will be much greater when considering the unknown composition in clinical samples, which can have great variability, particularly in bacterial load and pH.

A phenotypic AST rapid enough for the POC would be paradigm-shifting for Ng [39] because it would provide the correct timely treatment of infections, significantly reduce disease burden, and improve global surveillance efforts [40–42]. Until a POC diagnostic is developed for Ng, empiric prescribing of the last-line dual antibiotic therapy of AZM/CRO will likely continue, as it has in the US over the last 5 y [43]. Likewise, if informed antibiotic prescriptions cannot be made, resistance will continue to spread, at which point no currently available antibiotics will be recommended for treatment of Ng. Importantly, a rapid, phenotypic AST would greatly increase treatment options because if clinicians know which antibiotics will be efficacious for each infection, they can once again treat with antibiotics that are not prescribed in the current (empiric-based) system because of the risk of resistance. For example, even though cefixime (CFM) is no longer used as a first-line therapy for Ng, up to 95% of infections in the US are still susceptible to CFM [1,44]. Similarly, up to 77% of Ng infections are susceptible to tetracycline (TET) [1]. Therefore, having a POC AST could enable clinicians to once again safely prescribe CFM and other antibiotics [45]. Several recent cases of Ng infections resistant to AZM [46,47], or the currently recommended combination of AZM/CRO[10,12], were detected after treatment was administered, highlighting the critical need for faster diagnostics.

For an Ng AST to inform treatment decisions at the POC, the total assay time to determine phenotypic susceptibility must be greatly decreased [48–50]. Quantification of pathogen-specific nucleic acid (NA) concentrations has shown major promise for the rapid determination of susceptibility phenotype [51–54]. These methods rely on comparing the NA concentrations of control and antibiotic-treated samples and thus work well for rapidly dividing organisms and for antibiotics that directly affect NA replication. NA-based phenotypic AST methods also benefit from the high sensitivity of NA amplification, and fast isothermal amplification techniques have led to short total assay times [51]. For example, by measuring the concentration of Escherichia coli DNA, we have shown that the antibiotic-exposure step for phenotypic AST can be shortened to 15 min [55]. We also were able to achieve a phenotypic AST with a 10-min antibiotic-exposure time in Ng by measuring changes in RNA concentration after exposure to ciprofloxacin (CIP), which directly inhibits DNA replication and downstream translation [56]. However, for antibiotics that do not impact DNA replication or gene expression on short timescales, such as β-lactams, these NA-based AST techniques have proven difficult; the fastest published method for Ng still requires 4 h of β-lactam exposure [57]. Importantly, of the antibiotics prescribed for Ng, only one, CIP [56], has been demonstrated to be compatible with this existing NA-based approach.

In this work, we asked two questions. (1) Is it possible to use NA quantification to measure β-lactam susceptibility phenotype of Ng very rapidly, using antibiotic-exposure times (15–30 min) much shorter than the doubling time of Ng (1–2 h)? (2) Would such short-term antibiotic exposures predict the antibiotic resistance profile of Ng measured by plate growth assays over multiple days? To answer these questions, here we describe an innovation that enables a rapid, NA-based phenotypic AST for β-lactams, the largest class of antibiotics used to treat Ng. We hypothesized that cell wall damage caused by exposure to β-lactams could be exploited to determine phenotypic susceptibility faster than cell division. Our method, termed nuclease-accessibility AST (nuc-aAST), measures the accessibility of intracellular Ng DNA to exogenously added nucleases after a short antibiotic exposure. We also wished to test whether the total time of the assay could be further decreased by including an enhancement step, defined as a condition that would lead to greater differences in DNA accessibility between resistant and susceptible samples.

We chose to validate this proof-of-concept nuc-aAST using three β-lactams, penicillin (PEN), CFM, and CRO. Each of these three antibiotics represent first-line treatments at different points in the history of Ng treatment [58,59]. Additionally, CRO, in combination with AZM, is the current recommended (and last-line) treatment for Ng. Determining susceptibility to CRO is thus relevant not only for treatment but for surveillance efforts. Clinical urine samples were chosen (and urine was chosen as the matrix for contrived samples) because urine is one of the primary sample types used for Ng diagnosis, especially in males [6,59]. We chose to test only categorically susceptible or resistant isolates, based on EUCAST breakpoints [60], because susceptible and resistant isolates are more useful than intermediate isolates for gaining initial mechanistic insights into nuc-aAST, and because susceptible and resistant are actionable calls in antibiotic-prescribing scenarios. Lastly, keeping in mind clinical utility, we timed each assay step to determine whether the nuc-aAST could yield a definitive susceptibility call within the time period of a patient’s visit, which is usually less than an hour [49,50].

Results

Design and rationale of the nuc-aAST

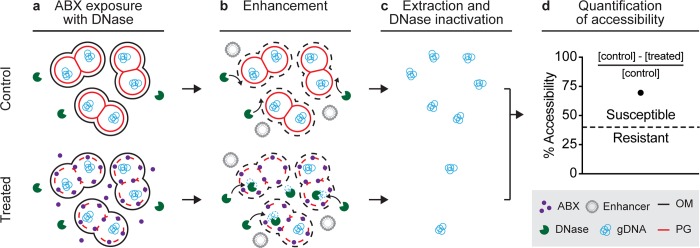

The nuc-aAST method measures differences in the accessibility of genomic DNA to an exogenous nuclease between control and treated samples following a short antibiotic exposure. Like other NA-based AST methods, the nuc-aAST (Fig 1) relies on measuring changes in the quantity of pathogen-specific NAs in response to a treatment with an antibiotic; however, the nuc-aAST differs from existing NA-based ASTs in three aspects. First, in nuc-aAST, exposure of cells to β-lactams is performed in the presence of a DNase enzyme to degrade any DNase-accessible NAs (Fig 1A). DNA is accessible to DNase if it is released from the cells upon cell lysis or if the action of the antibiotic porates the cells and allows DNase to access the intracellular DNA. Second, in nuc-aAST, an enhancement step is introduced to increase accessibility of DNA in cells that have damaged or compromised peptidoglycan caused by β-lactams; DNase is present and active during this enhancement step (Fig 1B). Third, in nuc-aAST, lysis of the sample is performed only after DNase has degraded all accessible DNA (Fig 1C). This lysis step also inactivates the DNase, so that the enzyme does not impact downstream quantification (S1 Fig). Following inactivation of DNase and lysis, DNA remaining in the sample is quantified and the percentage of accessible DNA is used to determine susceptibility (Fig 1D). The percentage of accessible DNA is quantified by subtracting the concentration of inaccessible DNA (DNA not digested) in the treated aliquot from the concentration of DNA in the control aliquot and dividing this value by the concentration of DNA in the control. Measuring the percentage of accessible DNA is an NA-based metric that enables quantification of the damage to the cellular envelope induced by antibiotics targeting cell wall biosynthesis.

Fig 1. The nuc-aAST workflow shown for a sample containing a β-lactam susceptible pathogen.

(a) A sample is split into control and treated aliquots; the treated aliquot is exposed to ABXs in the presence of DNase, and any extracellular DNA is digested. ABXs compromise PG of cells in the treated aliquot. (b) Accessibility to nucleases is enhanced by the addition of an enhancer, which disrupts the OM. gDNA becomes accessible and is degraded in the treated aliquot. Intact PG in control samples (or in treated but resistant samples) prevents degradation. (c) NAs are extracted, and DNase is inactivated. (d) Accessibility is quantified by measuring NA concentrations in the control and treated aliquots and dividing the amount of digested DNA by the amount in the control (to yield percentage accessibility). When the percentage accessibility is greater than the threshold (dashed line), the sample is categorized as susceptible. ABX, antibiotic; gDNA, genomic DNA; NA, nucleic acid; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antibiotic susceptibility testing; OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan.

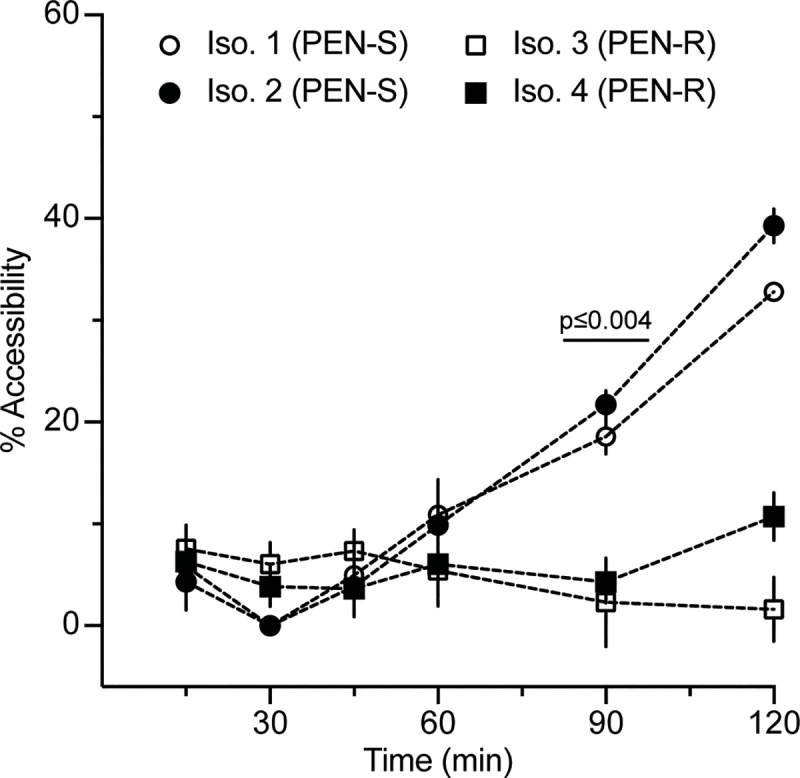

β-lactams should primarily affect peptidoglycan [61] and should not have a major impact on the outer membrane (OM), which serves as a structural element in gram-negative bacteria [62]. Therefore, we expected the primary mechanism behind any increase in accessibility to be cell lysis as a result of exposure to β-lactams, leading to release of genomic DNA to the extracellular environment containing DNase. Additionally, we hypothesized that autolysis, which has been observed as an active stress response in Ng [63,64], might accelerate changes in accessibility due to antibiotic exposure. We tested our hypotheses in a time-course experiment using two PEN-susceptible and two PEN-resistant Ng clinical isolates (Fig 2). We observed a significant difference in the percentage accessibility between susceptible and resistant isolates after 90 min of exposure. This is the shortest incubation time for an Ng AST with PEN to date and faster than existing NA-based methods that rely on DNA replication [57]. However, the ideal length of an exposure step for an AST at the POC would be even shorter (15–30 min) to keep the entire workflow within the time period of a patient visit. Thus, we were compelled to further accelerate changes in accessibility of DNA to nuclease as a result of β-lactam exposure in susceptible samples.

Fig 2. Percentage accessibility of DNA over time using the nuc-aAST without the addition of an enhancing step.

Two PEN-S and two PEN-R Ng isolates were exposed to PEN in the presence of DNase I. DNA from the control and PEN-treated aliquots was extracted and quantified using qPCR at multiple time points to calculate percentage accessibility. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the PCR triplicates. Data are in S10 Table. Ng, N. gonorrhoeae; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antibiotic susceptibility test; PEN, penicillin; PEN-R, PEN-resistant; PEN-S, PEN-susceptible; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

Enhancing changes in accessibility

We next hypothesized that the differences in DNA accessibility that we observed between susceptible and resistant isolates exposed to β-lactams could be enhanced using conditions that would increase the permeability of the cell envelope. In gram-negative organisms like Ng, the OM presents the first, and major, permeability barrier to macromolecules (e.g., nucleases and other enzymes) entering or exiting the cell, typically allowing only small molecules with molecular weights approximately <600 Da to pass through [65,66]. The peptidoglycan, in contrast to the OM, is a looser barrier that has been estimated to allow macromolecules up to 50 kDa to pass through [67–69]. We thus suspected that if the OM could be compromised, damage to the peptidoglycan would result in immediate, measurable changes in accessibility of genomic DNA to DNase, both by allowing DNase to enter and by allowing DNA fragments to exit. Therefore, we hypothesized that we could compromise the OM using an “enhancer” to decrease total assay time.

The ideal enhancer would (1) increase DNA accessibility to DNase in cells that have a compromised cell wall as a result of antibiotic exposure, (2) result in minimal lysis of healthy cells, (3) have a consistent effect on all Ng isolates, and (4) have no effect on downstream extraction and quantification of NAs. With these parameters in mind, we chose to test hypo-osmotic stress, stimulated autolysis, and four classes of surfactants as potential enhancers.

Hypo-osmotic stress was chosen as a method to enhance lysis of cells with damaged or compromised cell walls because osmotic stress of varying degrees is known to increase release of intracellular contents in gram-negative bacteria [70–72], although it has never been used to enhance accessibility in the context of AST. We exposed cells to hypo-osmotic conditions by diluting control and treated aliquots 20-fold in water with DNase I and 500 μM CaCl2, resulting in an approximately 244-mOsm/kg shift from the antibiotic-exposure conditions. Autolysis was chosen as an enhancer with the rationale of leveraging an already existing stress response in Ng to enhance changes in DNA accessibility. Autolysis is a natural stress response in Ng and can be accelerated by incubation in high-pH conditions (e.g., Tris [pH 8.5]) [73,74]. We hypothesized that using autolysis as an enhancer might result in large changes in NA accessibility. Surfactants were chosen as potential enhancers as a targeted chemical means of disrupting the bacterial cell membrane. We chose a representative surfactant from each of the four major charge-based classes of surfactants to investigate whether surfactant charge might lead to variability in their effectiveness due to natural variations in the OM of Ng. We tested the anionic surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), the cationic surfactant benzalkonium chloride (BAC), the nonionic surfactant TERGITOL NP (TNP), and the zwitterionic surfactant 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS). Each of these surfactant classes, with the exception of zwitterionic surfactants, have been well studied for their ability to compromise the integrity of the cell envelope [75], but none have been used in the context of AST or to change DNA accessibility on such short timescales. We chose to include the less well-studied zwitterionic surfactant CHAPS based on the diverse interactions of zwitterionic solutes with the bacterial cell envelope [76].

We tested each potential enhancer with respect to (1) the degree of lysis caused by incubation with the enhancer alone, (2) the ability to differentiate PEN-susceptible and PEN-resistant isolates using an enhancement step after exposure to PEN, and (3) the ability to differentiate CRO-susceptible and CRO-resistant isolates using an enhancement step after exposure to CRO, and (4) the ability to differentiate CFM-susceptible and CFM-resistant isolates using an enhancement step after exposure to CFM. We chose to use PEN, CRO, and CFM because we expected that the degree of change in NA accessibility as a result of enhancement would depend on the type of β-lactam used during exposure. CRO, CFM, and PEN bind and inhibit a different profile of penicillin-binding proteins [45,77] and have different rates of killing [78], which we expected would lead to different effects depending on the enhancer. Each enhancer was tested using multiple isolates susceptible or resistant to either PEN, CRO, or CFM. All enhancers were tested using a 5-min enhancement step after 15 min of antibiotic exposure. Antibiotic-exposure and enhancement steps were performed separately to decouple their effects on the Ng isolates.

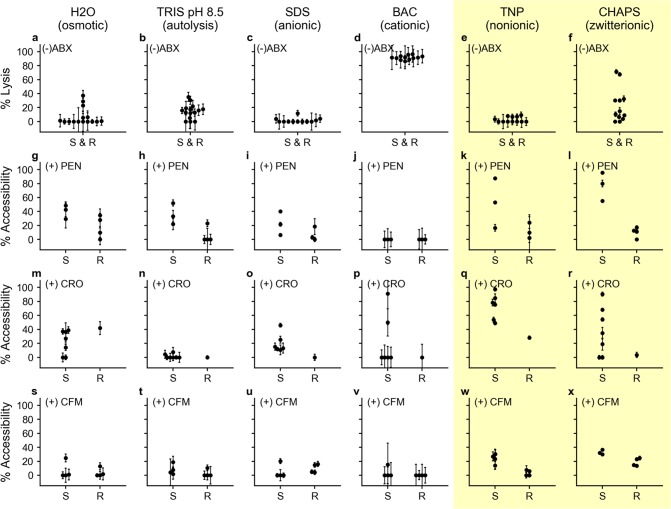

Enhancers were first tested for the degree of lysis caused by a 5-min incubation with the enhancer alone (Fig 3A–3F). If the enhancement step lyses the majority of cells even without antibiotic exposure, then DNA accessibility will increase in both control and treated aliquots, and any effect of the antibiotic will be diminished. We observed an average of <50% lysis when testing all potential enhancers except BAC (Fig 3D), which showed an average of 91.6% lysis across all 12 isolates tested (See S2 and S3 Tables for data).

Fig 3. Selection of enhancers.

(a-f) Six enhancers were tested for percentage of cell lysis due to enhancer alone (prior to ABX exposure). (g-l) Enhancement after 15-min exposure to PEN. (m-r) Enhancement after 15-min exposure to CRO. (s-x) Enhancement after 15-min exposure to CFM. Each point represents a clinical isolate run as a single experiment for that condition. All PCR was performed in technical triplicates with error bars representing the error in the PCR measurement propagated for the calculation of percentage lysis or percentage accessibility; all numerical values are available in S2 Table and S3 Table. The yellow shading indicates the two enhancers (TNP and CHAPS) most promising for nuc-aAST. Data for (a-f) are in S2 Table and (g-x) are in S3 Table. ABX, antibiotic; BAC, benzalkonium chloride; CFM, cefixime; CHAPS, 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; CRO, ceftriaxone; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antibiotic susceptibility testing; PEN, penicillin; R, resistant; S, susceptible; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; TNP, TERGITOL NP.

We next measured the percentage DNA accessible when using each enhancer after a 15-min exposure to PEN. We evaluated the ability to differentiate PEN-susceptible and PEN-resistant isolates based on the average percentage accessibility in susceptible isolates (which we want to be large), the average percentage accessibility in resistant isolates (which we want to be small), and the magnitude of separation between those two values. Based on these criteria, Tris (Fig 3H), TNP (Fig 3K), and CHAPS (Fig 3L) were the most promising enhancers for differentiating PEN-susceptible and PEN-resistant isolates after 15 min of exposure. However, we observed differences in DNA accessibility in response to CRO and CFM compared with PEN depending on the enhancer used (Fig 3M–3X). Among CFM-susceptible isolates, the responses to antibiotics and each enhancer were smaller than in PEN-susceptible and CRO-susceptible isolates. TNP and CHAPS were the only tested enhancers that enabled us to differentiate CRO-susceptible and CRO-resistant responses (Fig 3W–3X) after 15 min of CFM exposure. We were unable to observe consistently large changes in the seven tested CRO-susceptible isolates using the other two ionic surfactants, SDS (Fig 3I and 3O) and BAC (Fig 3J and 3P), regardless of the antibiotic treatment. Following these tests, we chose CHAPS as the enhancer to use for validation of the nuc-aAST with clinical isolates because it resulted in low-percentage lysis, large increases in DNA accessibility for PEN-susceptible and CRO-susceptible isolates following exposure, and only small increases in the DNA accessibility of PEN-resistant, CRO-resistant, and CFM-resistant isolates.

Validation using clinical isolates

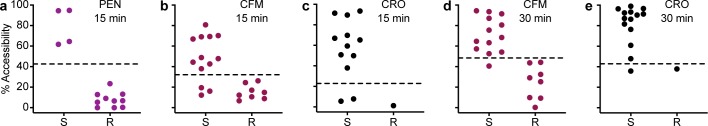

To validate the nuc-aAST, we performed 48 ASTs (with at least three biological replicates each) using 21 clinical isolates of Ng exposed individually to PEN, CFM, or CRO for 15 min. We then compared the categorical susceptibility determined using the nuc-aAST to the susceptibility determined using gold-standard agar dilution (Fig 4A–4C). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots [79] (S4 Fig) were created so that the area under the curve (AUC) could be calculated separately for each β-lactam tested. After 15 min of exposure, we obtained an AUC of 1.000 (PEN), 0.875 (CFM), and 1.000 (CRO). The AUC is determined by scanning a threshold through the ROC plot and measuring the sensitivity and specificity at each theoretical threshold value. This scanning allows one to select the threshold that would differentiate susceptible and resistant organisms with the maximum sensitivity and specificity within the given dataset. For example, an AUC of 1.000 indicates there was a threshold value that perfectly separated susceptible and resistant categories. However, AUC measurements do not consider the experimental noise or the magnitude of separation between susceptible and resistant samples and should be applied with care to datasets with limited numbers of measurements, such as ours. For example, in the case of CRO, the difference between the single CRO-resistant isolate that was available to us and the two CRO-susceptible isolates with the lowest responses was small after 15 min of exposure. Therefore, setting the susceptibility threshold between them would be impractical, even though it would yield 100% categorical agreement. We therefore decided to set a single threshold for all three antibiotics at a more conservative 26.5% even though this threshold generates some errors in both the CFM and CRO measurements after 15 min of antibiotic exposure. This threshold was chosen because it generated the fewest number of errors with 15 min of CFM exposure. The exact value is the average of the closest susceptible and resistant isolate.

Fig 4. Validation of nuc-aAST using clinical isolates.

(a-c) nuc-aAST results after 15 min of exposure to (a) PEN, (b) CFM, and (c) CRO. (d-e) nuc-aAST results after exposure to (d) CFM and (e) CRO for 30 min. Each point represents the average for a single isolate run in (at least) biological triplicate for that condition. All PCR was performed in technical triplicate. The dashed line represents the susceptibility threshold, which was set at 26.5% accessibility for 15-min exposures and 46% for 30-min exposures. Data plotted are in S4 Table; experimental data from individual replicates are detailed in S11 Table and S12 Table. AST, antibiotic susceptibility testing; CFM, cefixime; CRO, ceftriaxone; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility AST; PEN, penicillin; R, resistant; S, susceptible.

We then hypothesized that the differences observed in the magnitude of the response of the susceptible isolates after 15 min of exposure to each antibiotic, including the errors observed when testing CFM and CRO, could be the result of differences in how fast each β-lactam affects Ng [78]. For example, a possible explanation for differences among isolates in their response to antibiotics could be phylogenetic differences [80–82]. If isolates differ in their response times, a longer exposure would result in larger average separation between susceptible and resistant isolates and potentially better categorical agreement if the susceptible isolates were less responsive as a result of a delayed response to antibiotic.

To test the hypothesis that there are inherent differences in isolate response time, we performed nuc-aAST using CFM and CRO with 30-min exposure times, and as predicted, we observed a larger average separation between susceptible and resistant isolates and only a single error with each antibiotic. After 15 min of exposure to CFM and CRO, 77% and 83% of susceptible isolates, respectively, were classified as susceptible using nuc-aAST. After 30 min of exposure to CFM and CRO, 95% and 92% categorical agreement was obtained for CFM and CRO, respectively. The AUC for CFM and CRO after 30 min of exposure were 0.917 and 0.981, respectively (S4 Fig).

Pilot nuc-aAST tested directly on clinical urine samples

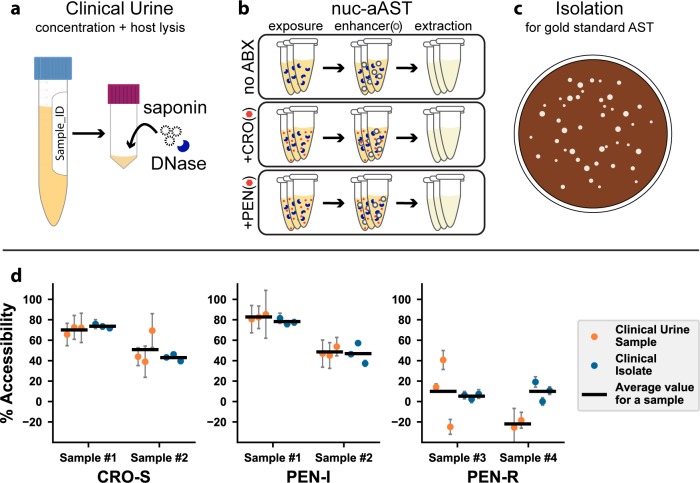

Our long-term goal, well beyond the scope of this manuscript, is to develop phenotypic AST assays and devices for clinical settings. As a proof of concept that our nuc-aAST method is aligned with that goal, we performed pilot nuc-aAST experiments directly on fresh clinical urine samples without a culturing step (see Methods). We note that a phenotypic Ng AST has never been successfully performed directly on clinical samples by any method; the gold-standard AST requires isolation of the pathogen, and then the AST is performed on the isolate. At the time we began this pilot, it was unknown whether it would even be possible to obtain an AST result directly from a clinical sample without a culturing step. The stability and viability of Ng in urine samples has never been characterized, and to reduce the unknown variables, these proof-of-concept nuc-aAST were performed on fresh clinical samples. We set up a satellite lab at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF) clinic where samples were obtained. The nuc-aAST method depends on DNase I functionality, so we first ran control experiments with a spike-in of lambda DNA into three different urine samples to show that DNase I remained active under the conditions and timeframe we are testing (data shown S2 Fig). All clinical urine samples reported herein were run immediately after collection (in all four samples, the sample handling began within 30 min of sample donation). Not all clinical samples were positive or yielded AST results (some samples were negative for Ng and some could not be reliably quantified; see Methods for details). Six nuc-aASTs were obtained directly on four clinical urine samples, including four with PEN and two with CRO. All nuc-aAST experiments were performed with technical triplicates.

To perform nuc-aAST and gold-standard comparison, each clinical urine sample was divided into two parts; one part was used immediately to run the nuc-aAST and one part was cultured to obtain the isolates for the gold-standard culture-based AST. For the nuc-aAST (Fig 5A and 5B), clinical urine was first centrifuged to concentrate, then resuspended in culture media with saponin (to selectively lyse host cells) and DNase I (to clear free DNA from host and dead bacterial cells) for a 15-min incubation [83–85]. The suspension was centrifuged again and then resuspended in fresh Graver-Wade medium (GWM). Next, the sample was exposed to antibiotics (PEN or CRO) or the control solution (nuclease-free water [NF-H2O]) for 30 min. Then, all samples were exposed to the enhancer TNP for 3–5 min. DNA concentrations were measured with quantitative PCR (qPCR) and the data analyzed as described in the Methods. The results from each experimental replicate are shown in Fig 5D.

Fig 5. Pilot nuc-aAST with clinical urine samples.

(a) Clinical urine samples were concentrated by a factor of 5 and incubated with DNase I and saponin for 15 min to lyse host cells and clear free DNA. (b) The nuc-aAST protocol was performed in technical triplicates with no ABX, CRO, or PEN. Each nuc-aAST consisted of a 30-min exposure to 1 μg/mL CRO or PEN followed by a 3–5 min exposure to the enhancer TNP (see Methods for details). (c) Each clinical sample was isolated for gold-standard MIC testing and further experiments. (d) Results of six nuc-aASTs were performed directly on four clinical urine samples and susceptibility was determined (orange points). In parallel, isolates were prepared from these clinical samples, and the results of the rapid nuc-aAST with clinical urine samples were compared to the same protocol with the prepared isolate (blue points). The means of the replicates are shown as horizontal lines (S7 Table). The MIC was determined by the gold-standard method (S1 Table). Error bars are the error in the PCR measurement propagated for the calculation of percentage lysis or percentage accessibility (S6 Table). ABX, antibiotic; AST, antibiotic susceptibility testing; CFM, cefixime; CRO, ceftriaxone; CRO-S, CRO-susceptible; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility AST; PEN, penicillin; PEN-I, PEN-intermediate; PEN-R, penicillin-resistant; TNP, TERGITOL NP.

To perform the gold-standard culture-based AST, the second part of each of the four clinical urine samples was plated and subcultured on selective media, and over the course of 3–5 d, isolates were prepared (details in “MIC testing and creation of clinical isolates” in the Methods). Gold-standard agar-dilution minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing was performed on these isolates, and the resulting MICs are reported in Fig 5D and S1 Table. We emphasize that gold-standard AST information was obtained days after nuc-aAST experiments. The isolates from each of these four clinical urine samples were then handled identically to the urine samples, including saponin and DNase I pretreatments, and the nuc-aAST was repeated. The results of the direct-from-sample nuc-aAST and the results of the nuc-aAST on the isolate from these clinical samples are reported in Fig 5D to compare the performance. The nuc-aAST results of the clinical urine sample and the isolate carried out with the same method gave comparable results; notably, the clinical data are (as expected) more variable among replicates, which is partially the result of bacterial loads in the urine sample being lower than in the assay run on isolates. A threshold at 46% accessibility (Fig 4) correctly categorized all six ASTs from the clinical samples (S7 Table) as antibiotic resistant or not antibiotic resistant.

The pilot nuc-aAST experiments with clinical samples were run with a slightly modified workflow compared with the isolates. For example, we used a slightly shorter enhancement step, and we used TNP instead of CHAPS as the enhancer to minimize background lysis of bacterial cells. Additionally, we only encountered PEN-intermediate (PEN-I) Ng and PEN-resistant Ng. Because we are testing one concentration of antibiotics (1 μg/mL) in the nuc-aAST, which is above the MIC of the PEN-I Ng and below MIC of the PEN-resistant Ng, as expected PEN-I Ng gave a susceptible (or “not resistant” [NR]) call and PEN-resistant Ng gave a resistant call.

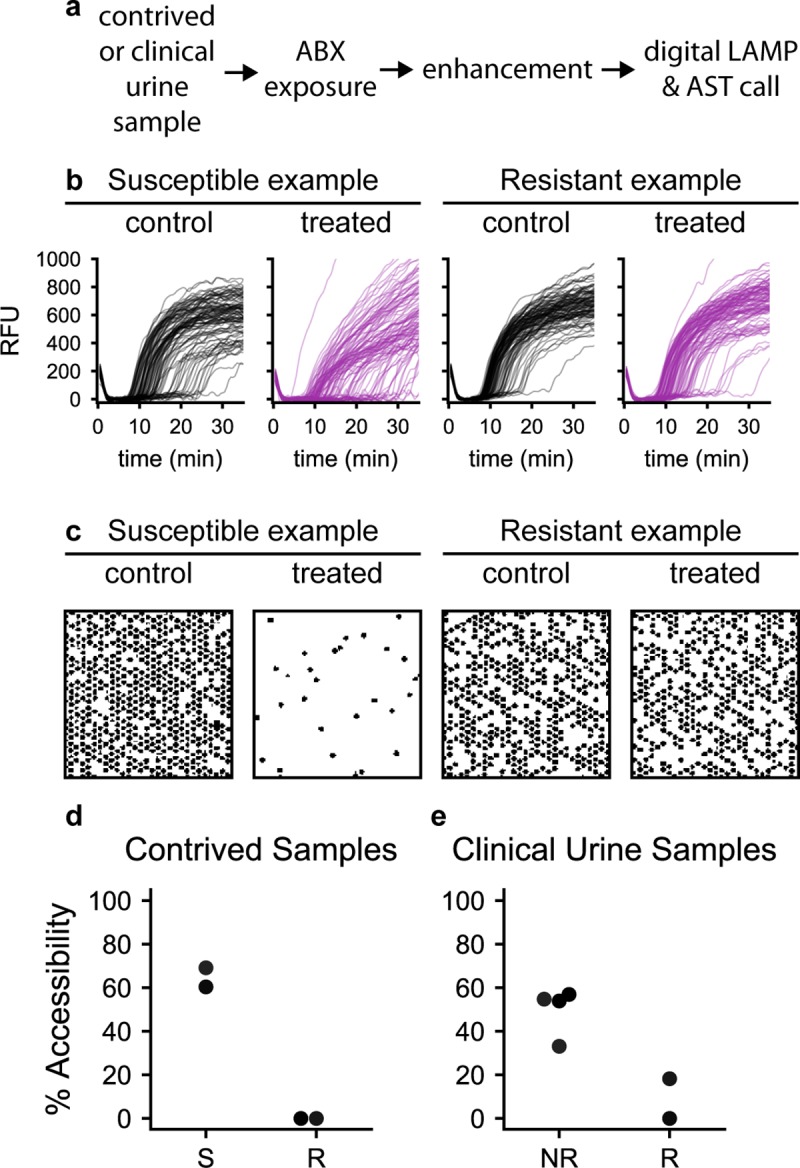

Sum-of-steps total time using contrived urine samples

To make a more realistic measure of total assay time, we modified the extraction and quantification steps of the nuc-aAST. The exposure and enhancement steps were performed as described previously, but NA quantification was performed using a rapid, chip-based, digital loop-mediated isothermal amplification (dLAMP) method, as described previously [86]. Additionally, we used a faster, single-step NA extraction method based on previous work [51]. Both modifications made the workflow faster. Additionally, the high precision of digital quantification allowed us to make a susceptibility call as soon as there was a significant difference between the concentration of NAs in the control and treated aliquots.

We measured total assay time based on the sum of the steps of the nuc-aAST using contrived urine samples. Contrived samples mimic clinical urine samples and allowed us to better evaluate how the assay would perform in a clinical setting compared with assays performed with isolates in media. Samples were created using two PEN-susceptible and two PEN-resistant isolates; one of the two PEN-resistant isolates was positive for β-lactamase activity, which we included in order to have PEN-resistant isolates with different mechanisms of resistance. To perform the AST, samples were first split into control and treated aliquots and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Next, the samples were transferred to the enhancement step and incubated for 5 min in the presence of CHAPS. Samples were then extracted as described previously, and dLAMP was performed in commercial chips [86]. Images were obtained in real time using a custom imaging system [87]. LAMP quantification was performed using an automated data-analysis workflow in MATLAB [86] in which images are automatically processed and positive wells counted based on a digitized mask created from the final image (Fig 6B). NA concentrations were used to determine percentage accessibility as soon as the measured NA concentrations in the susceptible sample became significantly different between the control and treated chips. All samples were tested in a total time (measured as the sum of steps) of 30 min and agreed with gold-standard agar dilution (Fig 6D). Performance of dLAMP was evaluated on extractions from clinical sample nuc-aAST experiments (Fig 6E). The extension of the dLAMP reaction is a result of low NA concentrations present in the clinical samples (data shown in S5 Table).

Fig 6. The nuc-aAST workflow for contrived and clinical urine samples with each step timed.

(a) The nuc-aAST workflow times required for contrived samples are 15-min ABX exposure, 5-min enhancement, 2 min for DNA extraction, 8 min for digital LAMP and AST call; timing for clinical urine samples includes 30-min ABX exposure, 3–5-min enhancement, 10 min for extraction, and 20 min for digital LAMP and AST call. (b) Amplification curves from which positive wells were determined and counted (a subset of 100 wells is shown for each microfluidic chip, S1–S4 Data) (c) A 2 × 2-mm subsection of masks was created from chips used for performing digital LAMP on control and antibiotic-treated aliquots of S and R samples; as an illustration, each mask shows approximately 625 wells (out of about 20,000 total wells) after 10 min of amplification. Wells that showed amplification of Ng DNA appear black. (d) The percentage of accessible DNA was determined at earliest significance (7–8 min of amplification; see Methods and S5 Table) for two penicillin-S and two penicillin-R samples run using digital LAMP (S5 Table). Each step was timed individually, and the sum of steps of the assay was 30 min. (e) Percentage accessibility was determined after 20 min of digital LAMP for a representative technical replicate for each of the six nuc-aAST performed directly on four clinical urine samples. Ceftriaxone-S and penicillin-intermediate samples are plotted together as NR (S5 Table; MICs are in S1 Table). ABX, antibiotic; AST, antibiotic susceptibility testing; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; Ng, N. gonorrhoeae; NR, not resistant; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility AST; R, resistant; RFU, relative fluorescence units; S, susceptible.

Discussion

Here, we described a new approach—nuc-aAST—to enable developing a critically needed rapid phenotypic AST for the globally important pathogen Ng. We show that by measuring the change in the accessibility of DNA after 15- or 30-min β-lactam exposure, the nuc-aAST yields a phenotypic susceptibility readout in less than 1 h, as opposed to the currently available methods, which require hours to days. We further show that the nuc-aAST breaks the current speed limits for NA-based phenotypic ASTs using β-lactams (which do not directly impact NAs) by using an innovative approach: coupling cell wall damage to NA readout. The nuc-aAST thus provides a new approach for designing rapid phenotypic ASTs with NA-based readouts for antibiotics that impact cell envelope integrity. Overall, we envision that leveraging the nuc-aAST and combining it with other creative biological and chemical insights will result in similarly innovative approaches for other important antibiotic classes for Ng, such as protein-biosynthesis inhibitors like TET and AZM. Existing NA-based approaches, such as those for CIP [25,56], can also be combined alongside the nuc-aAST.

We found that phenotypic ASTs that use NA accessibility as a readout benefit from the use of a carefully chosen enhancer. Here, the enhancement step consisted of a surfactant (CHAPS) that enabled detection of cell wall damage faster than cell division. Without the enhancement step, the cell envelope remains intact longer, so measurements of DNA accessibility approximate the timescale of cell division (Fig 2), which, for fastidious organisms such as Ng, will be too slow for POC applications. Furthermore, on the timescales tested here, DNA release in susceptible, treated samples may in part be the result of β-lactams “porating” the cell wall or cells lysing as a result of stress. Cell wall turnover may also proceed even if cells are not actively dividing. In both cases, the enhancement step is critical to shorten the time required to detect a difference between control and antibiotic-treated samples. The increase in DNA accessibility in susceptible isolates will differ based on the combination of β-lactam used and enhancer, highlighting the importance of testing multiple β-lactams with the nuc-aAST. Of the surfactants tested as enhancers, the charge-neutral surfactants TNP and CHAPS gave better results than the ionic surfactants SDS and BAC, suggesting that charge may be an important factor when designing an effective enhancement step. We also anticipate that organism-specific OM chemistry and general stress responses will play a role in determining which enhancers are optimal in other organisms.

We found that for PEN, susceptibility of Ng could be determined after just 15 min of exposure in all isolates tested (Fig 4A). However, for CFM and CRO, a small number of susceptible isolates did not respond after 15 min of exposure, but almost perfect categorical agreement was obtained after 30 min of exposure (Fig 4B–4E). We hypothesize that CFM and CRO required a longer exposure than PEN because of their differences in binding kinetics and rates of killing [77,78,88]. Despite these differences, an actionable susceptibility call (i.e., determining that a susceptible isolate is susceptible to a particular antibiotic and therefore can be treated with that antibiotic) could still be made for most isolates after 15 min of exposure. The errors yielded from the nuc-aAST at 15 min of antibiotic exposure would not result in ineffective treatment because these errors are from susceptible isolates (three CFM-susceptible and two CRO-susceptible) that were misidentified as resistant. We emphasize that in our isolate dataset, these errors are reduced to one CFM-susceptible and one CRO-susceptible isolate by extending the antibiotic incubation time by just 15 min. One approach to balance reducing assay time with minimizing errors is to perform two exposures in parallel for each antibiotic. The first exposure would be analyzed after 15 min. If a response is obtained indicating that the pathogen is susceptible (which should be the case for the majority of patients), the second exposure would be discarded. If no response or if an equivocal response is obtained, then the second exposure (after 30 min total) would be analyzed to provide the definitive susceptibility call. With this approach, the test would provide the answer after 15 min of antibiotic exposure for the majority of patients, and only a few patients would be delayed by the additional 15 min of antibiotic exposure.

Several limitations will need to be overcome in order to translate the nuc-aAST approach to an automated and distributable system. First, in this paper, we used clinical isolates, contrived urine samples, and four clinical urine samples. Although contrived samples are a good proxy for clinical samples and are accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration in certain cases [89], we also wished to perform a pilot experiment to demonstrate the nuc-aAST can work directly on fresh clinical samples. Our six nuc-aAST experiments gave good agreement with the ASTs that were run on isolates taken from the same samples (Figs 5 and 6). These pilot data suggest that the nuc-aAST can be adapted to work directly on clinical urine samples without the need for a culturing step and can utilize existing dLAMP techniques from crude lysate of a clinical sample. Because there is no rapid (20 min) POC Ng ID test currently available, we had to run ASTs without knowing whether the samples are positive for Ng; as expected, not all clinical samples collected yielded interpretable AST data (see Methods). Further development will be needed to optimize the nuc-aAST for clinical use. Performing phenotypic AST on clinical samples is extremely challenging and has only been demonstrated a few times, many from clinical urinary tract infection (UTI) samples [51,53,90,91]. This manuscript is a demonstration of a phenotypic AST used directly on Ng clinical samples. Many recent breakthroughs in phenotypic AST are initially reported without any validation with clinical samples; most papers use isolates [56,81], contrived samples [57,92–94], or positive blood cultures [95] instead of raw clinical samples. Second, future work should test more Ng isolates to encompass broader phylogenetic diversity [80–82] when they are made available to researchers and characterized, as well as test isolates with intermediate resistance to PEN, CFM, and CRO. These efforts could also aim to establish a correlation in the magnitude of nuc-aAST response and MIC of antibiotics, which would provide even more detailed information at the POC. Third, in timing the sum of steps, we did not include handling time; future work should include optimization of handling steps and timed sample-to-answer experiments. Finally, the nuc-aAST method will need to be translated to a POC device so that larger-scale clinical evaluations can be performed. Devices for multiplexed digital quantification [96–98] have been demonstrated and would be useful in performing nuc-aAST for multiple antibiotics in parallel.

We envision that nuc-aAST would be deployed in combination with two complementary technologies: (1) the pathogen ID technologies that are being developed by others [20,21,23,24] to identify Ng-positive samples that require an AST and (2) rapid genotypic and/or phenotypic ASTs that rely on NA readouts for other antibiotics used in the treatment of Ng, including fluoroquinolones (CIP) [25,51,81] and protein synthesis inhibitors (TET and AZM) [81]. Assuming these two complementary technologies are developed and validated, further development of nuc-aAST would provide the last—and we would argue the most challenging—piece needed for a complete rapid ID/AST workflow for Ng based on NA readout. We chose NA readout for the nuc-aAST for two reasons. First, NA readouts will enable easy integration with pathogen ID and other NA-based AST technologies. Second, NA readouts are organism specific [51] and therefore should be effective even for mixed microbial populations potentially present in clinical samples (e.g., Ng in the presence of commensals or other pathogens).

Implementation of a rapid phenotypic AST would dramatically improve the antibiotic stewardship of Ng infections and therefore impact the health of people who are infected with Ng; currently, there are an estimated 78,000,000 global cases of Ng every year [99]. Furthermore, the nuc-aAST approach provides a framework for developing additional accessibility-based AST chemistries for other pathogens that pose global-health threats but have been challenging for current phenotypic AST methods. For example, we have shown that quantifying NA accessibility to polymerases can be used to rapidly determine antibiotic susceptibility in Enterobacteriaceae [100]. Overall, this work highlights the diagnostic capabilities that can be attained by developing innovative NA-based assays for AST; further expansion and application of these approaches are critically needed to address the crisis posed by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Methods

Ethics statement

Clinical urine samples were collected at the AHF clinic under Caltech IRB #18–0865 from consented male patients symptomatic for Ng.

Study design

The objective of this study was to develop a rapid phenotypic AST for β-lactams based on DNA accessibility to nuclease for use with Ng. The key hypotheses of this work were as follows: (1) following antibiotic exposure, DNA in susceptible cells would be more accessible to an exogenously added nuclease than DNA in resistant cells because of cell wall damage as a result of exposure to antibiotics; (2) this difference would occur faster than cell division; and (3) this difference in DNA accessibility could be detected sooner if a surfactant enhancement step was included. To test the first two hypotheses, we performed an exposure time course using two PEN-susceptible and two PEN-resistant clinical isolates of Ng. To test the third hypothesis, we performed 48 nuc-aASTs using 21 clinical Ng isolates (exposed to antibiotics for 15 min) and 36 nuc-aASTs using 21 clinical Ng isolates (exposed to antibiotics for 30 min). We then compared the results to gold-standard agar dilution.

To calculate the sample size, the methods and Eq 5 from [101] were used as described previously [51]. Namely, we suspected that the specificity and sensitivity of the nuc-aAST method would be 95% with a desired margin of error of ±10%. Under these conditions, 18.2 (or 19) samples must be tested with the nuc-aAST method and compared to the gold standard. For 15-min antibiotic exposures, we performed 29 ASTs with isolates susceptible to the antibiotic being tested and 19 ASTs with isolates resistant to the antibiotic being tested.

Isolates and agar-dilution MIC testing

Isolates were provided by the University of Washington Neisseria Reference Laboratory and the CDC Antibiotic Resistance (AR) Isolate Bank N. gonorrhoeae panel (S1 Table). MICs of the CDC AR Isolate Bank are reported by the CDC [102], and MICs of all other isolates were determined by agar dilution according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [103].

Reagents and culture media

BD BBL Chocolate II Agar prepared plated media (GC II Agar, with Hemoglobin and BD IsoVitaleX) was purchased from VWR International LLC (VWR, Radnor, PA). GWM was prepared as described previously [38]. Cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton II Broth (MHB) (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was prepared according to manufacturer instructions. All sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and calcium chloride (CaCl2) (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) stocks were dissolved in NF-H2O and sterilized using 0.2-μm filters. DNase I (2,000 U/mL) was obtained from New England Biolabs (NEB; Ipswich, MA). Normal urine from pooled human donors was purchased from Lee Biosolutions (Maryland Heights, MO) and filtered through 0.2-μM filters before use.

Antibiotic stocks were prepared and stored as single-use aliquots at −80°C. Aliquots were thawed once and diluted in NF-H2O before use. PEN (1 mg/mL) was prepared from penicillin G sodium salt (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in NF-H2O. CRO (1 mg/mL) was prepared from ceftriaxone disodium salt hemi(heptahydrate) (Sigma) in NF-H2O. CFM (5 mg/mL) was prepared from cefixime trihydrate (Sigma) in DMSO.

Unless otherwise noted, enhancer stock solutions were prepared in NF-H2O and stored at room temperature. Tris buffer (500 mM [pH 8.5] at 37°C) was prepared according to the Sigma buffer reference tables [104] using 0.2-μm filter sterilized stocks of 1 M Tris-HCl (Sigma) and 1 M Tris base (Fisher Scientific) prepared in milliQ H2O. TNP HLB 13.1 (100 mM) was prepared by mixing 334 μL 100 mM Tergitol NP-9 (Sigma) + 666 μL 100 mM Tergitol NP-10 (Sigma). CHAPS (200 mM) was prepared from CHAPS solid powder (Sigma). SDS (0.1%) was prepared by diluting 10% SDS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). BAC (10%) was prepared from benzalkonium chloride solid powder (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA).

NA quantification

qPCR was performed using ssoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in 10 μL reactions with 500 nM primers targeting the Ng 16S rRNA gene [105]. DNA template composed 10% of the reaction volume. Cycling conditions consisted of 3.0 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, 15 sec at 62°C, and 20 sec at 72°C. All qPCR was performed on either a Roche LightCycler 96 or Bio-Rad CFX96 instrument. The Cq values obtained from qPCR are used to compute the percentage accessibility and percentage lysis as described in the following equations. Any negative percentages were set to 0 for plotting.

| (1) |

| (2) |

σ = standard deviation

μ = mean

| (3) |

| (4) |

σ = standard deviation

μ = mean

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) was performed using QX200 ddPCR Supermix for EvaGreen (Bio-Rad) with the same primers and primer concentrations used in qPCR. DNA template composed 10% of the reaction volume. Cycling conditions consisted of 5.0 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C, and 30 sec at 72°C, followed by a droplet stabilization step of 4°C for 5 min and 95°C for 5 min. Calculations of percentage accessibility and percentage lysis for ddPCR are given in the following equations, where λ represents template concentration in copies/μL. The template concentrations are used to compute percentage accessibility and percentage lysis as described in the following equations. Any negative percentages were set to 0 for all analyses.

| (5) |

| (6) |

A dLAMP assay was performed using a previously published system [86]. The dLAMP mix consisted of 1 μL NEB Isothermal Amplification Buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 500 mM KCl, 100 mM [NH4]2SO4, 1% Tween 20 [pH 8.8]), 0.6 μL MgSO4, 0.5 μL BSA (20 mg/mL), 0.4 μL Syto-9 (50 μM, prepared within 2 wk of use), 1.4 μL dNTPs (10 mM each), 0.5 μL 20X primer mix, 0.4 μL NEB Bst 2.0 WarmStart, 0.2 μL Ambion RNase cocktail, 4.0 μL NF-H2O, and 1 μL of template. Primers were designed to target the Ng 16S gene and screened as described previously [51]. Primer sequences used are as follows, with the final concentration in the amplification mix in parentheses: GCGGTGGATGATGTGGATT (forward outer primer, 0.2 μM), CCGGCAGTCTCATTAGAGTG (backward outer primer, 0.2 μM), CTCCTCCGTCTCCGGAGGATTCaaaaCGATGCAACGCGAAGAAC (forward inner primer, 1.6 μM), TCGTCAGCTCGTGTCGTGAGATttttCCCAACCGAATGATGGCA (backward inner primer, 1.6 μM), CGCACATGTCAAAACCAGG (forward loop primer, 0.4 μM), and GCAACGAGCGCAACCC (reverse loop primer, 0.4 μM). Eq 3 was used to compute percentage accessibility, where λ represents the template NA concentration in copies/μL as measured by dLAMP.

Ng culture preparation

Isolates were streaked from glycerol stocks stored at −80°C onto BD BBL Chocolate II Agar plates and incubated overnight in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Isolates were then passed onto fresh BD BBL Chocolate II Agar plates and grown for 4–7 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. In all experiments, cells from plates passed 1–3 times were used. Several colonies were scraped and resuspended in 37°C GWM to generate a working suspension. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured, and the working suspension was diluted to create a 2 mL working culture of OD600 0.05 in GWM in 15-mL polypropylene culture tubes. Cultures were incubated, with 500 rpm shaking, at 37°C + 5% CO2 for 3–5 h prior to antibiotic exposure.

nuc-aAST time course without enhancing step

Working cultures of Ng isolates were prepared as described in “Ng culture preparation.” Incubation at 37°C was performed in 100 μL reaction volumes in PCR tube strips on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. Treated samples consisted of 77.5 μL MHB, 2.5 μL NaHCO3 (200 mM), 5 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 5 μL PEN (20 μg/mL), and 10 μL working Ng isolate culture. PEN was replaced with NF-H2O in control samples. A 10-μL aliquot of each sample was extracted at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min and diluted 10X in QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen, Middleton, WI), then heated for 6 min at 65°C followed by 4 min at 98°C on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. All sample handling following antibiotic exposure was performed using a multichannel pipette; qPCR and calculation of % accessibility were performed as described previously.

Enhancer use

Working cultures of Ng isolates were prepared as described in “Ng culture preparation.” Initial exposure was performed by incubating 100 μL control and treated samples at 37°C in PCR tube strips on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. Treated samples consisted of 75 μL MHB, 5 μL NaHCO3 (100 mM), 5 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 5 μL PEN or CRO (20 μg/mL), and 10 μL working Ng isolate culture. Antibiotics were replaced with NF-H2O in control samples. After 15 min of incubation, samples were vortexed and quick-spun, and aliquots of all samples were transferred to the enhancement step as described subsequently. After the enhancement step, 5 or 10 μL of all samples was extracted by diluting 10X in QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen) and heating for 6 min at 65°C followed by 4 min at 98°C on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. All sample handling following antibiotic exposure was performed using a multichannel pipette; qPCR and calculation of percentage accessibility was performed as described previously.

Osmotic and autolytic enhancing steps were performed in 100 μL volumes. The osmotic enhancing step consisted of 89.75 μL NF-H2O, 4.75 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 0.5 μL CaCl2 (100 mM, 0.2-μM filtered), and 5 μL initial exposure samples. The autolytic enhancing step consisted of 75 μL NF-H2O, 4.75 μL NaHCO3 (100 mM, 0.2-μM filtered), 10 μL Tris (pH 8.5) (500 mM), 4.75 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 0.5 μL CaCl2 (100 mM), and 5 μL of the sample exposed to antibiotic.

All surfactant-enhancing steps were performed in 50 μL volumes with 25 of the 50 μL consisting of initial exposure samples. In the TNP enhancement step, the remaining 25 μL consisted of 1.25 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 1.25 μL NaHCO3 (100 mM), 20 μL MHB, and 2.5 μL TNP (100 mM). In the CHAPS enhancement step, the remaining 25 μL consisted of 1.25 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 1.25 μL NaHCO3 (100 mM), 20 μL MHB, and 2.5 μL CHAPS (200 mM). In the SDS and BAC enhancement steps, the remaining 25 μL consisted of 1.25 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 1.25 μL NaHCO3 (100 mM), 17.5 μL MHB, and either 5 μL SDS (1% w/v) or BAC (1% w/v) respectively.

nuc-aAST validation

Working cultures were prepared and exposed to antibiotics, and enhancing steps were performed as described for the CHAPS enhancement step in the “enhancer selection” section. Extraction was performed as described previously. Treated samples in the initial exposure step had a final concentration of 1.0 μg/mL PEN, CFM, or CRO. Samples were excluded if the percentage lysis (Eq 2) due to CHAPS was >75%. If the percentage lysis was negative, the value was set to zero before averaging. Three to 13 biological replicates were performed for each isolate-antibiotic combination. Biological replicates included separate antibiotic exposure, control exposure, and no-enhancer controls.

Preparation of clinical sample suspensions

After initial urine collection by a patient, AHF research staff pipetted an 8–14-mL aliquot into a 15-mL conical tube. For each clinical sample, handling began within 30 min of the sample donation. A 1-mL aliquot of the clinical urine was centrifuged in a 2-mL screw-cap microcentrifuge tube (VWR) for 5 min at 1,000g (Eppendorf 5418). The supernatant was then immediately removed and the pellets resuspended in GWM to generate a working suspension. Next, a 320-μL aliquot of the working suspension was added to a mixture of 40 μL 10X DNase I Reaction Buffer (NEB), 20 μL, DNase I (2,000 U/mL) (NEB), and 20 μL Saponin (20% w/v; Cas#8047-15-2, TCI). The suspension was then vortexed, spun in a benchtop microcentrifuge at 2,000g for 2–3 sec (Labnet Spectrafuge Mini Microcentrifuge), and placed on a heat block (GeneMate Mini Dry Bath) at 37°C for 15 min. Next, the suspension was vortexed and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000g. The supernatant was removed and the pellet resuspended in a mixture of equal volume and concentration of GWM, DNase I Reaction Buffer, and DNase I, as described previoiusly.

Clinical sample nuc-aAST

Suspensions of clinical urine samples were prepared as described previously. All suspensions were generated, and the antibiotic-exposure step was initiated within 90 min of sample donation. The initial antibiotic exposure was performed by incubating 50 μL control and treated samples at 37°C in PCR tube strips on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. Treated samples consisted of 48.8 μL of suspension and 1.25-μL aliquot of PEN or CRO (40 μg/mL). Antibiotics were replaced with NF-H2O in control samples. After 30 min of incubation, samples were vortexed and quickly spun on a benchtop microcentrifuge (Labnet) at 2,000g for 2–3 sec, and 2.7 μL TNP (100 mM) was added to each sample for the enhancement step. Samples were then immediately vortexed, spun on a benchtop microcentrifuge (Labnet) at 2,000g for 2–3 sec, and incubated at 37°C for 3–5 min. After the enhancement step, 20 μL from each sample was extracted by diluting 5X in QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen) and heating for 6 min at 65°C followed by 4 min at 98°C on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. All sample handling following antibiotic exposure was performed using a multichannel pipette; qPCR and calculation of percentage accessibility were performed as previously described, with the modification that the qPCR mix included 2 μL of template per 10 μL PCR reaction instead of 1 μL template per 10 μL reaction.

When processing the NA measurements, sample-inclusion criteria were as follows: samples must have had a 16S DNA concentration in the no- antibiotic control tube of less than a Cq of 29 (which translates to approximately 200 copies of 16S DNA/μL DNA extraction or 20 copies/μL in the PCR or LAMP reaction). ASTs from clinical samples with a negative percentage accessibility calculated to be less than −30% accessibility, or those with only one usable replicate out of three, were excluded from analysis.

MIC testing and creation of clinical isolates

While each of the clinical samples was being run with the nuc-aAST protocol, a 5–10-mL aliquot of the same clinical urine sample was packaged and transported on ice from AHF (Los Angeles, CA) to the laboratory at Caltech (Pasadena, CA). At the Caltech lab, a 50-μL aliquot was plated onto Neisseria-selective media (Modified Thayer Martin II [MTMII] Agar; Fisher Scientific) and incubated for 24–72 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Four individual colonies were subcultured onto a fresh MTMII agar plate and incubated for 8–48 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. The agar plates were parafilm-sealed, packaged, and shipped overnight via FedEx at ambient temperature for isolation and gold-standard (agar-dilution) MIC testing at the Neisseria Reference Laboratory in Seattle, WA. Agar-dilution MIC testing was performed as previously described.

Clinical sample nuc-aAST repeated with clinical isolates

After we prepared the clinical isolate and ran the gold-standard agar-dilution MIC test, the isolate was shipped back from the Neisseria Reference Laboratory (Seattle, WA) to the Caltech laboratory (Pasadena, CA). The isolate was then grown according to the methods for “Ng culture preparation” previously described. The experimental steps for “Clinical sample preparation” and “Clinical sample nuc-aAST” were repeated using the cell suspension of the isolate instead of the urine sample. The data from these clinical isolates were then compared to the results of the nuc-aAST performed directly on the original clinical urine samples.

Timed sum of steps

Working cultures of Ng isolates used in Fig 4 were prepared as described in “Ng culture preparation,” and 1.5 mL of the cultures were pelleted at 2,500g for 2.5 min and resuspended in 150 μL normal human urine (Lee Biosciences) prewarmed to 37°C. Initial exposure was performed by incubating 100 μL control and treated samples at 37°C in PCR tube strips on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. Treated samples consisted of 65 μL MHB, 5 μL NaHCO3 (100 mM), 5 μL DNase I (2 U/μL), 5 μL PEN (20 μg/mL), and 20 μL Ng isolate suspension in urine. NF-H2O was used in place of PEN in control samples. A CHAPS enhancing step was performed as described previously. After the enhancement step, a 20-μL aliquot from each sample was extracted by diluting 5X in QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen) and heated for 1 min at 65°C followed by 1 min at 98°C on a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler. All sample handling following antibiotic exposure was performed using a multichannel pipette. Amplification was then performed using qPCR, ddPCR, or dLAMP. Extractions were diluted 2.5X in NF-H2O before use in dLAMP.

Osmolarity measurements

Osmolarity measurements were performed on a Model 3320 Osmometer (Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA). The instrument was calibrated with reference standards (Advanced Instruments) prior to experiments. Samples identical to the antibiotic-exposure condition (i.e., media, nuclease, etc.) and samples identical to the osmotic enhancing condition were prepared and measured. The volume that would normally comprise Ng culture was replaced with media.

Statistical analysis

p-Values for Fig 2 were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software from an unpaired, two-tailed t test comparing the averages of the three replicates of each susceptible sample to each resistant sample. A significance value of 0.02 was used for statistical significance. ROC plots used for setting susceptibility thresholds in Fig 4 were created using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of gold-standard susceptible samples correctly identified as susceptible by the nuc-aAST. Specificity was defined as the proportion of gold-standard resistant samples correctly identified as resistant by the nuc-aAST. Statistical analyses for Fig 6 (dLAMP measurements) were performed as published previously [51,106]. As in our previous publication [51], the control and treated concentrations are compared as a ratio for statistical analysis.

| (7) |

This concentration ratio is transformed into a percentage change for visualization purposes, but the ratio is assessed for statistical significance. Poisson statistics were used to calculate the confidence interval of the NA concentration for each measurement. The error in the concentration ratio, a term used in the calculation of percentage accessibility, is calculated with standard-error propagation methods:

| (8) |

A one-tailed Z-test, assuming a normal distribution, is used to calculate p-values for digital NA concentrations. A threshold value for significance is set as a ratio of 1.22, corresponding to a percentage accessibility of 18%.

| (9) |

A significance value of 0.05 was used for statistical significance. The p-values to determine significance in dLAMP experiments were computed using Microsoft Excel’s standard normal cumulative distribution function and Z-value.

Supporting information

After extraction/inactivation, Ng DNA was spiked into the extractions containing the inactivated DNase I and incubated at 37°C. The Ng DNA was not degraded, confirming the inactivation of the DNase I enzyme. The concentration of DNase I, the composition of the incubations, and the extraction conditions were all performed under the same conditions as the ASTs. Error bars are 98% confidence intervals for three PCR replicates [55]. Data are in S8 Table. AST, antibiotic susceptibility test; Ng, N. gonorrhoeae.

(TIF)

(a) The qPCR results for the lambda DNA spike-in for three different urine samples. (b) Percentage of DNA digested calculated from qPCR results with the same equations used previously (see Methods) to calculate percentage lysis. Data are in S9 Table. qPCR, quantitative PCR.

(TIF)

(a-c) Results of nuc-aAST after 15 min of exposure to (a) PEN, (b) CFM, or (c) CRO. (d-e) nuc-aAST results after exposure to (d) CFM or (e) CRO for 30 min. Each point represents the average for a single isolate run in (at least) biological triplicate for that condition; error bars represent the standard deviation from the biological replicates. All PCR assays were performed in technical triplicate. The dashed line represents the susceptibility threshold, which was set at 26.5% accessibility for 15-min exposures and 46% for 30-min exposures. Data are also plotted in Fig 4. (Data plotted here are in Table S4; experimental data from individual replicates are in S11 Table and S12 Table; MICs are in S1 Table). AST, antibiotic susceptibility test; CFM, cefixime; CRO, ceftriaxone; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility AST; PEN, penicillin.

(TIF)

ROC curves were generated from the data shown in Fig 4, S4 Table. The FPR is shown on the x-axis and the TPR is shown on the y-axis. The AUC is shown for each plot. (a-c) Results of nuc-aAST after 15 min of exposure to (a) PEN, (b) CFM, or (c) CRO. (d-e) The nuc-aAST results after exposure to (d) CFM or (e) CRO for 30 min. AUC, area under the curve; CFM, cefixime; CRO, ceftriaxone; FPR, false positive rate; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; PEN, penicillin; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TPR, true positive rate.

(TIF)

Isolates were obtained from the UW NRL, the CDC AR Isolate Bank, and isolates prepared by the authors from clinical urine samples obtained from consented patients at AHF under IRB #18–0865. The gold-standard MICs for the CDC AR Isolate Bank are from the literature and all other MICs were calculated as described in the Methods. Antibiotics included PEN, CRO, and CFM. AHF, AIDS Healthcare Foundation; AR, Antibiotic Resistance; CDC, Centers for Disease Control; CFM, cefixime; CRO, ceftriaxone; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; PEN, penicillin; UW NRL, University of Washington Neisseria Reference Laboratory.

(XLSX)

Cqs are measured from qPCR as reported in main methods and the mean of the three PCR triplicates is reported in the table. Eqs 3 and 4 are used to calculate the percentage lysis and the error in that calculation based on error propagation from the standard deviation of qPCR triplicates. Data are plotted in Fig 3A–3F; negative percentages were set to 0 for visualization, as described in Methods. Enhancers included CHAPS at a final concentration of 10 mM; nonionic surfactant TNP at a final concentration of 5 mM and an HLB of 13.1; cationic surfactant BAC at a final concentration of 0.1%; anionic surfactant SDS at a final concentration of 0.01%; Tris buffer (pH 8.5); nuclease-free water. BAC, benzalkonium chloride; CHAPS, zwitterionic surfactant 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; HLB, hydrophile-lipophile balance; qPCR, quantitative PCR; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; TNP, TERGITOL NP.

(XLSX)

The PCR Cq is measured by qPCR (see Methods) and the mean of the PCR triplicates is reported. Eqs 1 and 2 are used to calculate the percentage accessibility, and the error in that calculation is based on the error propagation of the standard deviation of qPCR triplicates. “Treated” indicates the isolate was exposed to an ABX; “control” indicates no ABX exposure. Data are plotted in Fig 3G–3X., negative percentages were set to 0 for visualization, as described in Methods. ABXs included PEN, CRO, and CFM. Isolate categories included S and R. ABX, antibiotic; CFM, cefixime; Cq, quantitation cycle; CRO, ceftriaxone; qPCR, quantitative PCR; R, resistant to ABX; S, susceptible to ABX.

(XLSX)

The mean percentage of accessible DNA is calculated from at least three biological replicates of that nuc-aAST condition in clinical isolates (details of individual replicates are shown in S11 Table and S12 Table). Additionally, we report the SEM and SD of the biological replicate nuc-aASTs. Each nuc-aAST used 1 μg/mL of ABXs followed by 5 min of CHAPS as an accessibility “enhancer.” Data are plotted in Fig 4, negative percentage accessibilities were set to 0 for visualization, as described in Methods. ABXs included PEN, CRO, and CFM. Isolates included S and R. ABX, antibiotic; CFM, cefixime; CHAPS, 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; CRO, ceftriaxone; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; PEN, penicillin; R, resistant to ABX; S, susceptible to ABX; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean.

(XLSX)

Contrived samples are nuc-aASTs performed with clinical Ng isolates spiked into healthy urine; assay conditions are 15-min exposures to 1 μg/mL ABX followed by 5-min exposure to the enhancer CHAPS. One of the three technical replicates from each of the six clinical urine sample nuc-aASTs (Fig 6D and S6 Table) was also run in dLAMP (Fig 6E and S5 Table). Assay conditions were fresh, clinical urine samples, run with 30-min exposures to 1 μg/mL ABX followed by 3–5-min exposure to the enhancer TNP. The concentration of the Ng 16S DNA is reported in copies/μL, and p-values are calculated as described in the “Statistical analysis” section of the Methods for dLAMP experiments. (Negative percentages were set to 0 for visualization, as described in Methods. In Fig 6E, ABX-susceptible and ABX-intermediate samples are plotted together under the category NR). ABXs included PEN, CRO, and CFM. ABX, antibiotic; CFM, cefixime; CHAPS, 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; CRO, ceftriaxone; dLAMP, digital loop-mediated isothermal amplification; Ng, N. gonorrhoeae; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; NR, not resistant; PEN, penicillin; TNP, TERGITOL NP.

(XLSX)

All nuc-aASTs were run with a 30-min ABX exposure and 3–5 min of TNP enhancement step. The internal isolate number and clinical sample name corresponds to the MIC values in S1 Table. The sample number corresponds to the clinical sample number reported in Fig 5D. The sample type refers to if the nuc-aAST results come from an assay run directly from the clinical urine sample or on the isolate prepared from that urine sample. Technical replicates are parallel nuc-aASTs run for each condition. The percentage accessibility is calculated from the qPCR measurements, and the error is propagated according to Eqs 2 and 3, as described for previous calculations. ABXs included PEN and CRO. ABX, antibiotic; CRO, ceftriaxone; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; qPCR, quantitative PCR; PEN, penicillin; TNP, TERGITOL NP.

(XLSX)

The data are summarized with the mean percentage accessibility calculated from the technical replicate nuc-aASTs (mean percentages accessibility are shown in Fig 5D). Additionally, the SEM and SD are reported from the technical replicate nuc-aASTs. The technical replicates in this table are only the replicates that met our criteria for inclusion as described in the Methods. ABXs included PEN and CRO. ABX, antibiotic; CRO, ceftriaxone; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; PEN, penicillin; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean.

(XLSX)

Data are plotted in S1 Fig. Mean Cq is computed from qPCR triplicates. Error bars are 98% confidence intervals for three PCR replicates [55]. Cq, quantitation cycle; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

(XLSX)

Mean Cq is calculated from PCR triplicates and error is calculated (as described in main Methods) for PCR triplicates. Percentage DNA digestion is calculated for each clinical sample from the samples with and without DNase I. The error in the PCR measurements is propagated for calculating the error bar in the percentage digestion of the spike-in DNA. Data are shown in S2 Fig. Cq, quantitation cycle.

(XLSX)

Data are plotted in Fig 2. ABX, antibiotic; R, resistant to ABX; S, susceptible to ABX.

(XLSX)

Replicate numbers refer to which biological replicate experiment the data are from. The PCR Cq is measured by qPCR (see Methods) and the mean of the PCR triplicates is reported. Eq 1 is used to calculate the percentage accessibility, and Eq 3 is used to calculate the percentage lysis. “Treated” indicates the isolate was exposed to an ABX; “control” indicates no ABX exposure. Data are used to calculate mean percentage accessibility for each isolate, which are plotted in Fig 4A–4C and S3 Fig and shown in S4 Table. ABXs included PEN, CRO, and CFM. Susceptibility was indicated by S, R, or I. ABX, antibiotic; CFM, cefixime; CHAPS, 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; Cq, quantitation cycle; CRO, ceftriaxone; I, intermediate MIC; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; Ng, N. gonorrhoeae; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; PEN, penicillin; qPCR, quantitative PCR; R, resistant to ABXs; S, susceptible to ABXs.

(XLSX)

Replicate numbers refer to which biological replicate experiment the data are from. The PCR Cq is measured by qPCR (see Methods), and the mean of the PCR triplicates is reported. Eq 1 is used to calculate the percentage accessibility, and Eq 3 is used to calculate the percentage lysis. “Treated” indicates the isolate was exposed to an ABX; “control” indicates no ABX exposure. Data are used to calculate mean percentage accessibility for each isolate, which are plotted in Fig 4D and 4E and S3 Fig and shown in S4 Table. ABXs included PEN, CRO, and CFM. Susceptibility was indicated by S or R. ABX, antibiotic; CFM, cefixime; CHAPS, 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; Cq, quantitation cycle; CRO, ceftriaxone; Ng, N. gonorrhoeae; nuc-aAST, nuclease-accessibility antimicrobial susceptibility testing; PEN, penicillin; qPCR, quantitative PCR; R, resistant to ABX; S, susceptible to ABX.

(XLSX)

(PDF)

A representative AST from one of the contrived samples using isolates was selected and the LAMP amplification curves from the first 100 positive wells are shown. These curves are plotted in Fig 6B. See also S2–S4 Data for the complete dataset used in Fig 6B. AST, antibiotic susceptibility test; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification.

(XLSX)

These are representative wells to show LAMP amplification curves. These curves are plotted in Fig 6B. A representative AST from one of the contrived samples using isolates was selected. See also S1, S3 and S4 Data for the complete dataset used in Fig 6B. AST, antibiotic susceptibility test; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification.

(XLSX)