Abstract

Palliative care has evolved over the past five decades as an interprofessional specialty to improve quality of life and quality of care for patients with cancer and their families. Existing evidence supports that timely involvement of specialist palliative care teams can enhance the care delivered by oncology teams. This review provides a state-of-the-science synopsis of the literature that supports each of the five clinical models of specialist palliative care delivery, including outpatient clinics, inpatient consultation teams, acute palliative care units, community-based palliative care, and hospice care. The roles of embedded clinics, nurse-led models, telehealth interventions, and primary palliative care also will be discussed. Outpatient clinics represent the key point of entry for timely access to palliative care. In this setting, patient care can be enhanced longitudinally through impeccable symptom management, monitoring, education, and advance care planning. Inpatient consultation teams provide expert symptom management and facilitate discharge planning for acutely symptomatic hospitalized patients. Patients with the highest level of distress and complexity may benefit from an admission to acute palliative care units. In contrast, community-based palliative care and hospice care are more appropriate for patients with a poor performance status and low to moderate symptom burden. Each of these five models of specialist palliative care serve a different patient population along the disease continuum and complement one another to provide comprehensive supportive care. Additional research is needed to define the standards for palliative care interventions and to refine the models to further improve access to quality palliative care.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past five decades, palliative care has evolved from a philosophy of care that focuses on the last days of life to a professional specialty that delivers comprehensive supportive care to patients with advanced illnesses throughout the disease trajectory. Conceptualized by Dame Cicely Saunders in the 1960s, the first model of care was community-based hospice care.1 In the 1970s, Balfour Mount coined the term palliative care and started the first palliative care unit in an acute care academic hospital in Montreal.2 This model of inpatient care was widely accepted and contributed to a rapid growth in inpatient palliative care teams worldwide. In the 1990s, several palliative care teams started to see patients in outpatient clinics, which paved the way for patients to gain access to palliative care earlier in the disease trajectory.3-6 Over the past decade, multiple landmark clinical trials confirmed the benefits of outpatient palliative care, which stimulated more interest and growth in this field.7,8 The model of palliative care continues to evolve to better serve a growing number of patients throughout the disease continuum while adapting to an aging population and the ever-changing landscape of novel cancer therapeutics. On the basis of the consolidated body of evidence,9-11 ASCO has published multiple statements to support the integration of palliative care, with a vision toward comprehensive cancer care by 2020.12-15

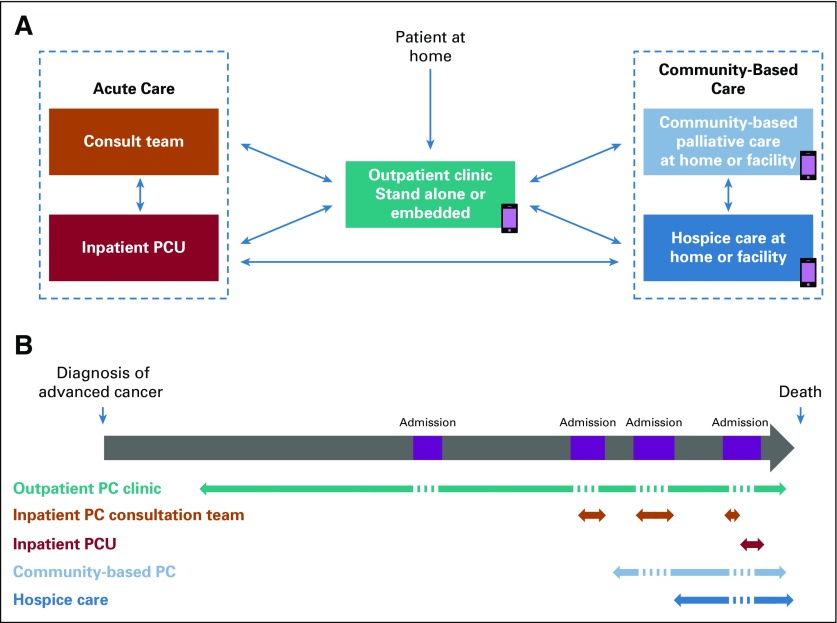

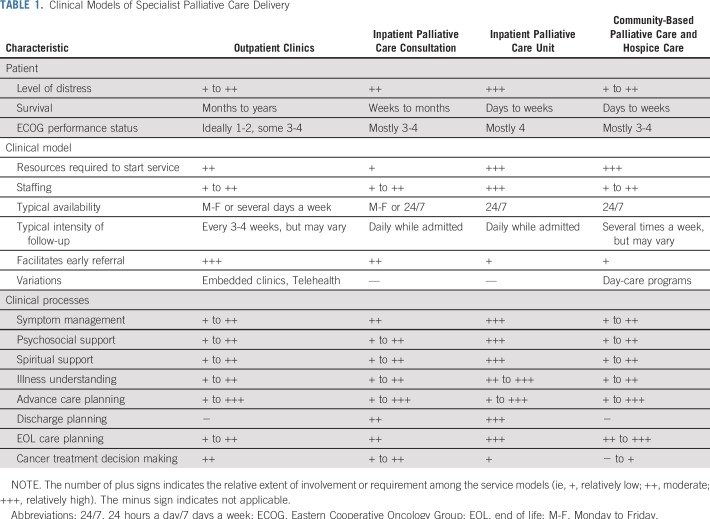

Currently, the five major service delivery models of specialist palliative care, namely outpatient palliative care clinics, inpatient palliative care consultation teams, acute palliative care units (APCUs), community-based palliative care, and hospice care, complement one another to provide comprehensive supportive care from diagnosis to the end of life. These five services differ in their team structures, care processes, patient populations, location of care, and reimbursement models16 (Fig 1; Table 1). Specialist palliative care, delivered by individuals with specialized training and expertise, complements and augments primary palliative care, which is basic symptom management and communication provided by nonpalliative care clinicians.17 In this article, we review the literature that supports each of the five specialist palliative care service delivery models and their variations. Conceptual models and primary palliative care have been discussed elsewhere.18,19

FIG 1.

Service models of specialist palliative care (PC). (A) Care anywhere. Outpatient clinics facilitate access to palliative care in the ambulatory setting while coordinating care with the other models of PC. Inpatient consultation teams and PC units (PCUs) are available at acute care facilities, whereas community-based PC and hospice care allow patients to be cared for in the ambulatory and community setting. The smartphone icon indicates telehealth outreach. (B) Care anytime. This figure highlights how the five service models complement one another to provide comprehensive PC along the entire disease continuum for patients and their families. The arrows indicate the general time frame of patient engagement.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Models of Specialist Palliative Care Delivery

OUTPATIENT PALLIATIVE CARE CLINICS

Compared with the other service models, outpatient palliative care clinics require relatively few resources, can serve a large number of patients, and represent the main setting for patients to be seen early along the disease trajectory20 (Table 1). In a 2010 national survey, 59% of National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated cancer centers and 22% of non-NCI–designated cancer centers offered outpatient palliative care.21 In 2015, 91% of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) cancer centers reported having outpatient palliative care clinics.22

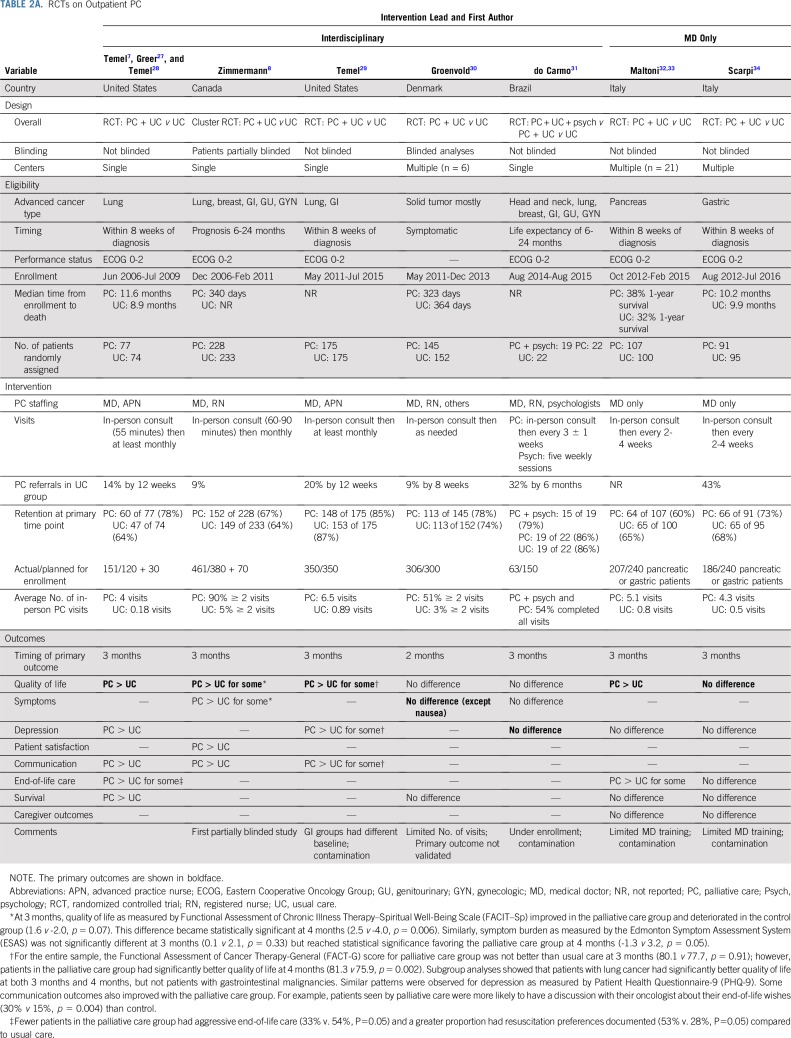

Several variations of outpatient palliative care interventions exist, including stand-alone clinics, embedded clinics, telehealth-based palliative care, and enhanced primary palliative care.23,24 Currently, much of the available evidence supports stand-alone clinics delivered by an interdisciplinary specialist palliative care team. Rabow et al25 conducted the first controlled trial on this model of delivery in 2004. Subsequently, a landmark randomized clinical trial that examined early outpatient palliative care was published in 2010.7 Patients who were within 2 months of diagnosis of stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer and had a performance status of 0 to 2 were randomly assigned to routine oncologic care with or without specialist outpatient palliative care. Early palliative care referral was associated with improved quality of life, depression, illness understanding, and survival.7,26-28 In a subsequent study, Zimmermann et al8 conducted a large cluster randomized trial in Canada that examined outpatient palliative care in patients with advanced solid tumors. The primary outcome of quality of life favored palliative care, although it did not reach statistical significance at 3 months and only became significant at 4 months. Secondary outcomes, including symptom burden, patient satisfaction, and patient-clinician communication, also improved with palliative care. To date, more than a dozen randomized trials have been published on variations of outpatient palliative care (Tables 2A and 2B). A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis that included seven of these studies confirmed the benefits of early palliative care.9 Outside the clinical trial setting, multiple retrospective cohort studies also reported that earlier referral is associated with better quality of end-of-life care outcomes.42,43 By reducing the prolonged hospitalizations and intensive care unit admissions near the end of life, early palliative care also may provide indirect health care savings through cost-avoidance measures and thus enhance the overall value of care.44

TABLE 2A.

RCTs on Outpatient PC

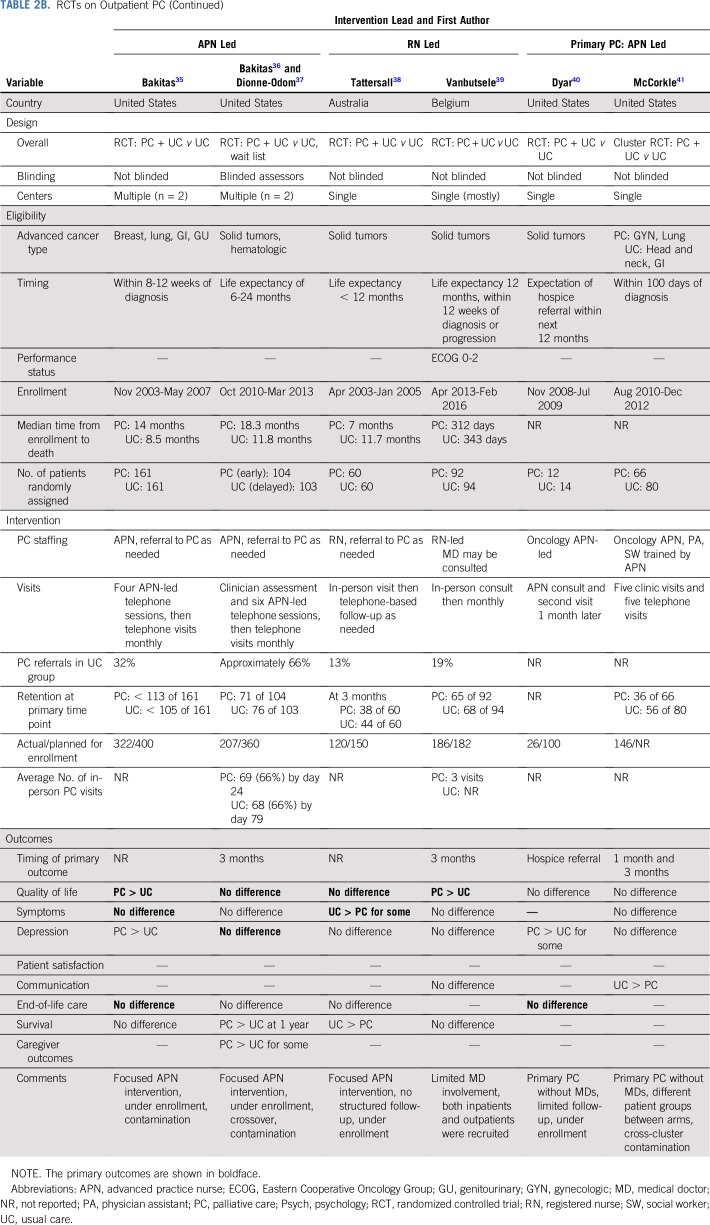

TABLE 2B.

RCTs on Outpatient PC (Continued)

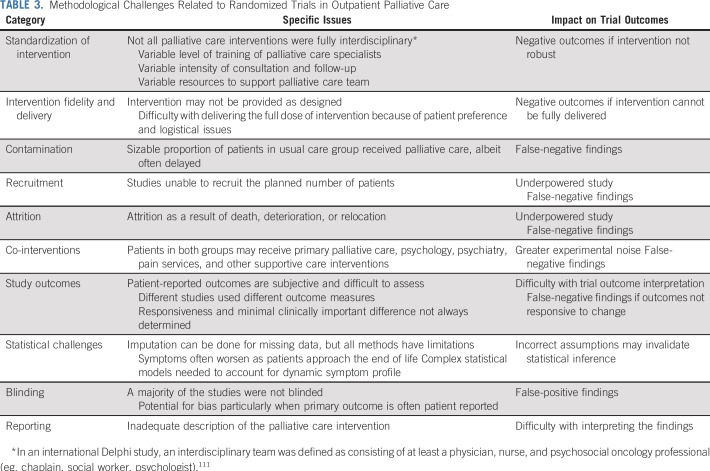

Tables 2A and 2B list the design and outcomes of contemporary trials. A few observations are noteworthy. First, much variation exists in the composition and training of interdisciplinary palliative care teams, comprehensiveness of intervention, timing of referral, and intensity of follow-up.24 In general, interdisciplinary interventions led by palliative medicine specialists7,8,29 have resulted in more-positive outcomes relative to a physician alone32-34 or nurse-led interventions35,36,38-41 (Tables 2A and 2B). This finding is not surprising because many palliative care interventions, such as methadone rotation and family meetings, are complex and require considerable expertise, planning, and resources, not unlike other sophisticated medical or surgical procedures. Second, contamination was a common issue, which made it increasingly difficult to include a usual care group.29,31,34-36 Third, these issues coupled with other methodological weaknesses, such as under enrollment (Table 3), explain why some recent studies have been negative. Methodologically sound trial designs are needed to minimize false-negative and false-positive findings.

TABLE 3.

Methodological Challenges Related to Randomized Trials in Outpatient Palliative Care

Across the nation, the structure of outpatient palliative care operations vary widely.21,22,45 Among 20 palliative care clinics at NCCN institutions, 43% had both physicians and advanced practice providers, 19% had physicians only, 10% had advanced practice providers only, and 29% were operated by others.22 These clinics saw an average of 469 new patients per year, with an average full-time equivalent of 3.3 clinicians. The average clinic duration was 60 minutes, and follow-up visits were 30 minutes.22 The MD Anderson Cancer Center has one of the largest programs in the United States. To overcome the potential stigma associated with the name palliative care among referring oncologists,48-48 this clinic changed its name to supportive care in 2007. In a before-and-after name change comparison, a significant increase in the time from referral to death (6.2 v 4.7 months) occurred.49 The number of patients referred to this clinic increased steadily from 750 in 2007 to 1,225 in 2013, which outpaced the growth of the cancer center.50 The interval from referral to death also increased from 4.8 to 7.9 months.48 Operating 5 days a week and staffed by four physicians, 12 nurses, and three counselors/psychologists, this clinic provided 1,772 new patient consultations and 6,943 follow-up visits in 2018. With a median survival of 10.3 months from time of referral, 72% of patients who attended this clinic believed that the timing of referral was appropriate.51

In an effort to standardize the processes for outpatient palliative care, investigators from several randomized trials have provided detailed descriptions of their interventions.7,8,29,39,52,53 Several groups also have characterized their outpatient clinic operations.54 In a qualitative thematic analysis of medical records, Yoong et al55 reported that palliative care was actively involved in managing symptoms, facilitating coping, establishing illness understanding, and engaging family members throughout the disease trajectory. The first two visits were more likely to involve relationship and rapport building and cancer treatment discussions and the last two visits were more likely to involve end-of-life planning and decision making around cancer treatments. Hoerger et al56 found that addressing coping was associated with improved quality of life and depressive symptoms, addressing treatment decisions was associated with a lower likelihood of initiating chemotherapy at the end of life, and addressing advanced care planning was associated with greater hospice care use.

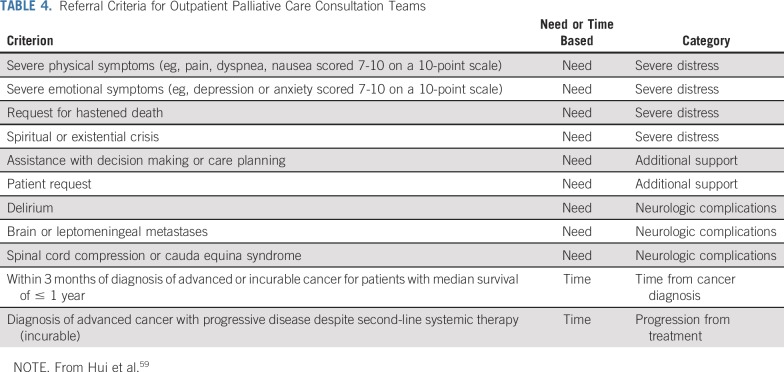

Much heterogeneity exists in the referral criteria for outpatient clinics.57 Although clinical trials support universal referral on the basis of time since diagnosis or prognosis, the current palliative care workforce may not be able to serve all patients with cancer, particularly when more patients are being seen earlier in the disease trajectory.58 Instead of time-based criteria, need-based referral criteria have been proposed to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from palliative care.59 Only one randomized trial has examined referral on the basis of symptom burden, and its interpretation was complicated by methodological issues30 (Table 2A). A recent Delphi study highlighted 11 major criteria for referral on the basis of an international consensus59,60 (Table 4). Additional research is needed to validate these criteria.

TABLE 4.

Referral Criteria for Outpatient Palliative Care Consultation Teams

Variations of Outpatient Palliative Care

Embedded clinics.

In a 2015 survey, 52% of the specialist palliative care clinics at NCCN cancer centers reported having embedded clinics. Although embedded clinics generally suggest that the palliative care team and the oncology team share the same clinic space and see the same patients on the same day, the nature of embeddedness is not always clearly articulated in the literature, and the distinction between embedded and stand-alone clinics is sometimes blurred.61-64 A few case series and nonrandomized controlled studies, which mostly involved advanced practice providers, have been reported with mixed findings.61-64 The strengths and weaknesses of the embedded model have been discussed in depth elsewhere.19,24

Telehealth interventions

Telehealth interventions may be the primary model of outpatient palliative care delivery, particularly for patients in rural areas where access to tertiary care is more challenging. In the Project Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends (ENABLE) II study, Bakitas et al35 compared patients randomly assigned to a nurse-led, predominantly telehealth-based palliative care intervention and usual care. The structured palliative care intervention was found to improve quality of life and mood but not symptom burden or quality of end-of-life care. Using a waitlist design, Project ENABLE III reported no difference in quality of life and symptom control between palliative care and usual care; 1-year survival was significantly longer in the palliative care group but not overall survival (Table 2B). However, Project ENABLE III was complicated by under enrollment and contamination.36 An ongoing randomized clinical trial aims to address whether face-to-face palliative care visits are equivalent to telehealth (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03375489).

Telehealth palliative care also may be provided as an outreach to augment existing outpatient clinics.65 Specifically, clinicians may be able to provide education, counseling, and symptom monitoring in a cost-effective manner with the potential to improve adherence, increase hospice referrals, and minimize acute care visits.66 Additional studies are needed to examine these outcomes.

Enhanced primary palliative care

Instead of referral to specialist palliative care teams, two randomized trials have examined the alternative model of enhanced primary palliative care provided by nurse practitioners in the oncology clinic.40,41 Neither trial provided clear evidence of benefits compared with usual oncologic care; however, both trials had significant methodological issues that complicated their interpretation (Table 2B). At this time, this model of care without specialist palliative care is not supported by available evidence.

INPATIENT CONSULTATION SERVICES

Inpatient palliative care consultation teams represent the backbone of palliative care. In the United States, approximately 90% of NCI-designated cancer centers reported having inpatient consultation teams.22,67 In 2010, 56% of non-NCI-designated cancer centers had an inpatient consultation service, and this proportion has been rising steadily.67 Palliative care consultants, including physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, and/or psychosocial professionals, typically have daily rounds with hospitalized patients. In contrast to outpatient palliative care, the median survival from referral to death is shorter, ranging from days to weeks and sometimes months.67

Several randomized studies have been conducted to examine the benefits of inpatient palliative care for patients with cancer. In a single-blind randomized trial, Grudzen et al68 compared inpatient palliative care consultation and routine care for patients with advanced cancer admitted through the emergency department. The palliative care team, which consisted of a physician, a nurse practitioner, a social worker, and a chaplain, focused on symptom management and care planning and followed patients daily while in the hospital. The palliative care group was associated with a significant improvement in quality of life at 12 weeks compared with usual care. This finding was interesting given the relatively short duration of the inpatient palliative care intervention during a short hospital stay (mean, 6 days), although some patients also received outpatient palliative care after discharge. No statistically significant difference was found in secondary outcomes, such as rates of depression, intensive care unit admissions, hospice discharge, and survival, albeit a trend favored the palliative care group.

The role of inpatient palliative care consultation also has been examined in patients admitted for hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. In a groundbreaking randomized clinical trial, El-Jawahri et al69 found that patients who received a palliative care referral had a better quality of life, lower depression, lower anxiety, and lower symptom burden at 14 days than patients who received care only from their transplantation team. During the hospitalization period with a median of 20 days, the palliative care team provided a median of eight visits. Only two patients in the control group had palliative care consultation. This beneficial effect was persistent at 3-month follow-up, and patients in the palliative care group also reported lower post-traumatic stress disorder.69 Caregivers also had lower rates of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder at 6 months post-transplantation.70 This study is unique because it involved the introduction of palliative care to patients with hematologic malignancies, some with curative potential. It highlights the added benefits of palliative care even when patients were already receiving intensive supportive care from a transplantation team. Moreover, palliative care had a positive impact on caregivers.

Inpatient palliative care referrals improve not only patient outcomes but also cost of care. Using propensity score analysis, multiple studies have reported that inpatient palliative care referral is associated with lower cost of hospitalization.71-73 A recent meta-analysis that combined data from six studies found that an inpatient palliative care consultation within 3 days of admission was associated with a cost savings of $4,251 per admission for patients with cancer.74

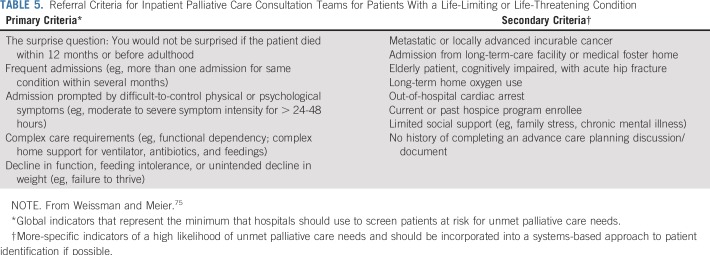

At this time, the existing palliative care infrastructure cannot accommodate universal referral of all hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. The Center to Advance Palliative Care has outlined several criteria for referral of patients to inpatient palliative care75 (Table 5). Continuity of care after discharge can be provided by outpatient palliative care and/or community-based palliative care (Fig 1).

TABLE 5.

Referral Criteria for Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation Teams for Patients With a Life-Limiting or Life-Threatening Condition

APCUs

Similar to the concept of intensive care units where medically complex patients receive life-sustaining therapies from highly specialized teams, APCUs are dedicated inpatient units where the interdisciplinary palliative care teams assume primary responsibility to deliver comprehensive care that addresses the physical, emotional, and spiritual domains of suffering for patients in severe distress. In addition to conventional acute care, the APCU teams often conduct complex interventions, such as rapid analgesic titration/rotation for intractable pain, palliative sedation for refractory agitated delirium, and facilitating difficult goals-of-care discussions and discharge planning.76-78

Because of the intensive nature of care, APCUs are likely to be found in larger hospitals with adequate resources to support larger palliative care teams. APCUs are currently only available in approximately 20% to 30% of cancer centers in the United States; in contrast, 70% of European Society for Medical Oncology–designated Centers of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care have APCUs.21,79 This discrepancy may be related to differences in health care culture and reimbursement policies.

Patients admitted to APCUs often have severe distress that would benefit from more intensive interdisciplinary management than what a typical inpatient consultation team can provide. The median survival of patients admitted to APCUs is typically in terms of days to weeks, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 30% to 50%.21 In one cohort of 2,568 APCU patients, 958 (33%) died during admission, 1,259 (43%) were discharged to hospice, 592 (20%) returned home without hospice, and 89 (3%) were discharged to health care facilities.67 Among those with a home discharge without hospice, 22% were alive at 6 months.67 A small proportion of patients received cancer therapy simultaneously.80

To our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial has specifically examined the outcomes associated with APCUs. However, findings from postdischarge surveys have been encouraging. In a large telephone survey of bereaved caregivers, Casarett et al81 compared the proportion of caregivers who perceived care received in the last month of life as excellent among patients treated in APCUs, consulted by an inpatient palliative care team, and who did not receive palliative care. APCUs were viewed more favorably than inpatient palliative care consults (propensity adjusted proportions, 63% v 53%; P = .04), which was, in turn, better than no palliative care (51% v 46%; P = .04). A cluster randomized trial found that institution of a comfort care pathway alone without specialist palliative care involvement did not result in better outcomes.82 Taken together, these studies suggest that APCUs may play a unique role in the delivery of care to patients at the end of life. In addition to comprehensive patient care, APCUs represent a unique setting for research to answer some critical questions at the end of life, such as signs of impending death and agitated delirium.83-85 More research is needed to examine which patients would most benefit from APCUs.

COMMUNITY-BASED PALLIATIVE CARE

Community-based palliative care programs provide in-person visits, equipment, supplies, and telephone support for patients at home or in community-based care facilities, such as nursing home and skilled nursing facilities. Only approximately 25% of cancer centers operate community-based palliative care teams, and other centers may contract palliative care services in the community.21 Patients enrolled in such programs typically are clinically stable and have a poor performance status, short expected survival, and a desire to continue care at ambulatory clinics (Fig 1; Table 1). Community-based palliative care programs differ from typical home care programs because they are staffed by palliative care teams and have a stronger expertise in end-of-life care.86

Multiple randomized controlled trials have examined variations of community-based palliative care.87-96 A majority of the studies were conducted before 2010, and the palliative care interventions have not been standardized. Meta-analyses found that home-based palliative care significantly increases the rate of home death.86,97 Moreover, community-based palliative care improves symptom control and satisfaction, although its impact on other outcomes, such as caregiver well-being and cost of care, is less conclusive.86,97 Similar to outpatient and inpatient models of palliative care, earlier involvement of community-based palliative care was associated with improved outcomes.98

More common in Europe, palliative day-care programs are available in the community setting to provide physical, psychological, social, and spiritual support for patients and respite and bereavement care for caregivers.99 These programs often are attached to an inpatient hospice unit.100 However, few studies have systematically evaluated the outcomes of such programs.100,101

HOSPICE CARE

The Medicare Hospice Benefit program was established in 1982 and covers hospice care at home or inpatient facilities. According to the Dartmouth Atlas Project, 63% of patients with cancer enrolled in hospice before death in 2012.102 Hospice care represents one of five service models of palliative care, although many clinicians and patients still have the misconception that the two are synonymous.46,47,103 In contrast to community-based palliative care, hospice care recipients are no longer seeking care at acute care facilities. Although patients with incurable cancer and a life expectancy of 6 months or less would qualify for hospice, the reality is that many postpone enrollment until the final weeks or days of life. Indeed, 16% died within 3 days of hospice enrollment in 2012.104 Of note, palliative care referral is associated with greater frequency and earlier hospice referral.61

Hospice care allows patients to be supported in the community and provides an alternative to dying in the hospital. In a randomized trial, Kane and colleagues105-107 reported that hospice care results in less depression and greater satisfaction with care compared with no hospice care but found no difference in other outcomes, such as pain management, hospital stay, or cost of care. Subsequently, large population-based studies found that hospice care was associated with lower rates of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, intensive care unit admissions, and costs of care in the last year of life.108,109

In conclusion, from hospice care to inpatient palliative care and outpatient clinics, palliative care has evolved over the past five decades as a professional specialty and refined its expertise to serve a greater population of patients and earlier in the disease course. The five models of palliative care complement one another to optimize care along the disease continuum for patients with cancer and their caregivers.

Existing evidence supports that early referral to interdisciplinary palliative care teams can improve patient and caregiver outcomes when added onto primary palliative care provided by the oncology team. Going forward, it is critical to define the standards and components of palliative care interventions while tailoring each to unique patient needs, care settings, and countries.110 For example, an international Delphi study reached the consensus that the minimum standard for an interdisciplinary palliative care team should consist of a physician, nurse, and a psychosocial team member.111 Active efforts are also under way to examine the impact of service model variations. Telehealth has the potential to provide greater palliative care access in a cost-effective manner. Furthermore, clinical initiatives and research studies are exploring how palliative care can be best positioned to deliver supportive care earlier in the disease trajectory (eg, patients with curable cancers) and to other groups less often seen by palliative care (eg, patients with hematologic malignancies or pediatric malignancies). More research also is needed to understand how primary palliative care delivered by oncologists and primary care teams can be integrated with specialist palliative care.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute grants (1R01CA214960-01A1, 1R21NR016736-01) (D.H.), an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research (MRSG-14-1418-01-CCE) (D.H.), and the Andrew Sabin Family Fellowship (D.H.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Models of Palliative Care Delivery for Patients With Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jco/site/ifc.

David Hui

Research Funding: Helsinn Therapeutics (Inst), Insys Therapeutics (Inst), TEVA Pharmaceutical Industries (Inst)

Eduardo Bruera

Research Funding: Helsinn Therapeutics

REFERENCES

- 1.Saunders C. The evolution of palliative care. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;41:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mount BM. The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;115:119–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruera E, Michaud M, Vigano A, et al. Multidisciplinary symptom control clinic in a cancer center: A retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:162–168. doi: 10.1007/s005200000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oneschuk D, Fennell L, Hanson J, et al. The use of complementary medications by cancer patients attending an outpatient pain and symptom clinic. J Palliat Care. 1998;14:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabow MW, Schanche K, Petersen J, et al. Patient perceptions of an outpatient palliative care intervention: “It had been on my mind before, but I did not know how to start talking about death... J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casarett DJ, Hirschman KB, Coffey JF, et al. Does a palliative care clinic have a role in improving end-of-life care? Results of a pilot program. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:387–396. doi: 10.1089/109662102320135270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD011129. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011129.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, et al. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;357:j2925. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:2104–2114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol 16:1986-1996, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps--from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:159–171. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Gunten CF. Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA. 2002;287:875–881. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: Establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4013–4017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:89–98. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finlay E, Rabow MW, Buss MK: Filling the gap: Creating an outpatient palliative care program in your institution. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book (38):111-121, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calton BA, Alvarez-Perez A, Portman DG, et al. The current state of palliative care for patients cared for at leading US cancer centers: The 2015 NCCN Palliative Care Survey. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:859–866. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabow MW, Dahlin C, Calton B, et al. New frontiers in outpatient palliative care for patients with cancer. Cancer Contr. 2015;22:465–474. doi: 10.1177/107327481502200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:356–376. doi: 10.3322/caac.21490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1310–1315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:834–841. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Damkier A, et al. Randomised clinical trial of early specialist palliative care plus standard care versus standard care alone in patients with advanced cancer: The Danish Palliative Care Trial. Palliat Med. 2017;31:814–824. doi: 10.1177/0269216317705100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.do Carmo TM, Paiva BSR, de Oliveira CZ, et al. The feasibility and benefit of a brief psychosocial intervention in addition to early palliative care in patients with advanced cancer to reduce depressive symptoms: A pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:564. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.004. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al: Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: A randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer 69:110-118, 2016 [Erratum: Eur J Cancer 69:110-118, 2016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: Results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2016;65:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4517-2. Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, Zagonel V, et al: Systematic vs. on-demand early palliative care in gastric cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial assessing patient and healthcare service outcomes. Support Care Cancer 1007/s00520-018-4517-2 [epub ahead of print on October 24, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438–1445. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1446–1452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tattersall MHN, Martin A, Devine R, et al. Early contact with palliative care services: A randomized trial in patients with newly detected incurable metastatic cancer. J Palliat Care Med. 2014;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:394–404. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dyar S, Lesperance M, Shannon R, et al. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: Results of a randomized pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:890–895. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E, et al. An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: A cluster randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:962–969. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743–1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang RW, Krzyzanowska MK, Zimmermann C, et al. Palliative care and the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:dju424. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung MC, Earle CC, Rangrej J, et al. Impact of aggressive management and palliative care on cancer costs in the final month of life. Cancer. 2015;121:3307–3315. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith AK, Thai JN, Bakitas MA, et al. The diverse landscape of palliative care clinics. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:661–668. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: What’s in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hui D, Park M, Liu D, et al. Attitudes and beliefs toward supportive and palliative care referral among hematologic and solid tumor oncology specialists. Oncologist. 2015;20:1326–1332. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui D. Definition of supportive care: Does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:372–379. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16:105–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dalal S, Bruera S, Hui D, et al. Use of palliative care services in a tertiary cancer center. Oncologist. 2016;21:110–118. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wong A, Hui D, Epner M, et al: Advanced cancer patients’ self-reported perception of timeliness of their referral to outpatient supportive/palliative care and their survival data. J Clin Oncol 35, 2018 (suppl; abstr 10121) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, et al. Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:459–464. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hannon B, Swami N, Pope A, et al. The oncology palliative care clinic at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre: An early intervention model for patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1073–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bischoff K, Yang E, Kojimoto G, et al. What we do: Key activities of an outpatient palliative care team at an academic cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:999–1004. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:283–290. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoerger M, Greer JA, Jackson VA, et al. Defining the elements of early palliative care that are associated with patient-reported outcomes and the delivery of end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1096–1102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hui D, Meng YC, Bruera S, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient palliative cancer care: A systematic review. Oncologist. 2016;21:895–901. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schenker Y, Arnold R. Toward palliative care for all patients with advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1459–1460. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hui D, Mori M, Watanabe SM, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e552–e559. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hui D, Mori M, Meng YC, et al. Automatic referral to standardize palliative care access: An international Delphi survey. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3830-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Einstein DJ, DeSanto-Madeya S, Gregas M, et al. Improving end-of-life care: Palliative care embedded in an oncology clinic specializing in targeted and immune-based therapies. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e729–e737. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.020396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muir JC, Daly F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walling AM, D’Ambruoso SF, Malin JL, et al. Effect and efficiency of an embedded palliative care nurse practitioner in an oncology clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e792–e799. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.020990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yennurajalingam S, Prado B, Lu Z, et al. Outcomes of embedded palliative care outpatients initial consults on timing of palliative care access, symptoms, and end-of-life quality care indicators among advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1690–1697. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pimentel LE, Yennurajalingam S, Chisholm G, et al. The frequency and factors associated with the use of a dedicated supportive care center telephone triaging program in patients with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riggs A, Breuer B, Dhingra L, et al. Hospice enrollment after referral to community-based, specialist palliative care: Impact of telephonic outreach. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hui D, Elsayem A, Palla S, et al. Discharge outcomes and survival of patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:49–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:591. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2094–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Greer JA, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care during hematopoietic stem-cell transplant on psychological distress 6 months after transplant: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3714–3721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:454–463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: Earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2745–2752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.May P, Normand C, Cassel JB, et al: Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 178:820-829, 2018

- 75.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elsayem A, Calderon BB, Camarines EM, et al. A month in an acute palliative care unit: Clinical interventions and financial outcomes. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:550–555. doi: 10.1177/1049909111404024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang H, Barysauskas C, Rickerson E, et al. The intensive palliative care unit: Changing outcomes for hospitalized cancer patients in an academic medical center. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:285–289. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eti S, O’Mahony S, McHugh M, et al. Outcomes of the acute palliative care unit in an academic medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:380–384. doi: 10.1177/1049909113489164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hui D, Cherny N, Latino N, et al. The ‘critical mass’ survey of palliative care programme at ESMO designated centres of integrated oncology and palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2057–2066. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hui D, Elsayem A, Li Z, et al. Antineoplastic therapy use in patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center: A simultaneous care model. Cancer. 2010;116:2036–2043. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, et al. The optimal delivery of palliative care: A national comparison of the outcomes of consultation teams vs inpatient units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:649–655. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Costantini M, Romoli V, Leo SD, et al. Liverpool care pathway for patients with cancer in hospital: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;383:226–237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61725-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hui D, dos Santos R, Chisholm G, et al. Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients. Oncologist. 2014;19:681–687. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hui D, Dos Santos R, Chisholm G, et al. Bedside clinical signs associated with impending death in patients with advanced cancer: Preliminary findings of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Cancer. 2015;121:960–967. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hui D, Frisbee-Hume S, Wilson A, et al. Effect of lorazepam with haloperidol vs haloperidol alone on agitated delirium in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1047–1056. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD007760. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grande GE, Todd CJ, Barclay SI, et al. Does hospital at home for palliative care facilitate death at home? Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;319:1472–1475. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hughes SL, Cummings J, Weaver F, et al. A randomized trial of the cost effectiveness of VA hospital-based home care for the terminally ill. Health Serv Res. 1992;26:801–817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH, et al. Quality of life in palliative cancer care: Results from a cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3884–3894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McWhinney IR, Bass MJ, Donner A. Evaluation of a palliative care service: Problems and pitfalls. BMJ. 1994;309:1340–1342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6965.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ, Donaldson G, et al. A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer. 1989;64:1375–1382. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890915)64:6<1375::aid-cncr2820640634>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McKegney FP, Bailey LR, Yates JW. Prediction and management of pain in patients with advanced cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1981;3:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(81)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McMillan SC, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: A clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walsh K, Jones L, Tookman A, et al. Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:142–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zimmer JG, Groth-Juncker A, McCusker J. A randomized controlled study of a home health care team. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:134–141. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shepperd S, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Straus SE, et al. Hospital at home: Home-based end-of-life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009231.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pellizzari M, Hui D, Pinato E, et al. Impact of intensity and timing of integrated home palliative cancer care on end-of-life hospitalization in Northern Italy. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1201–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Davies E, Higginson IJ. Systematic review of specialist palliative day-care for adults with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:607–627. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Higginson IJ, Gao W, Amesbury B, et al. Does a social model of hospice day care affect advanced cancer patients’ use of other health and social services? A prospective quasi-experimental trial. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:627–637. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kilonzo I, Lucey M, Twomey F. Implementing outcome measures within an enhanced palliative care day care model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. The Dartmouth Atlas Project: Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Lebanon, NH, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:659–685. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1564-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, et al. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: Independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3184–3189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kane RL, Berstein L, Wales J, et al. Hospice effectiveness in controlling pain. JAMA. 1985;253:2683–2686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kane RL, Klein SJ, Bernstein L, et al. Hospice role in alleviating the emotional stress of terminal patients and their families. Med Care. 1985;23:189–197. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kane RL, Wales J, Bernstein L, et al. A randomised controlled trial of hospice care. Lancet. 1984;1:890–894. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, et al. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312:1888–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Obermeyer Z, Clarke AC, Makar M, et al. Emergency care use and the Medicare hospice benefit for individuals with cancer with a poor prognosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:323–329. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e588–e653. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hui D, Bansal S, Strasser F, et al. Indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care programs: An international consensus. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1953–1959. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]