Abstract

Mounting evidence supports oncology organizations’ recommendations of early palliative care as a cancer care best practice for patients with advanced cancer and/or high symptom burden. However, few trials on which these best practices are based have included rural and remote community-based oncology care. Therefore, little is known about whether early palliative care models are applicable in these low-resource areas. This literature synthesis identifies some of the challenges of integrating palliative care in rural and remote cancer care. Prominent themes include being mindful of rural culture; adapting traditional geographically based specialty care delivery models to under-resourced rural practices; and using novel palliative care education delivery methods to increase community-based health professional, layperson, and family palliative expertise to account for limited local specialty palliative care resources. Although there are many limitations, many rural and remote communities also have strengths in their capacity to provide high-quality care by capitalizing on close-knit, committed community practitioners, especially if there are receptive local palliative and hospice care champions. Hence, adapting palliative care models, using culturally appropriate novel delivery methods, and providing remote education and support to existing community providers are promising advances to aid rural people to manage serious illness and to die in place. Reformulating health policy and nurturing academic-community partnerships that support best practices are critical components of providing early palliative care for everyone everywhere.

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is an essential component of high-quality cancer treatment and has been recommended by national and international organizations for all adult and pediatric patients with metastatic disease and high symptom burden.1-6 Despite these recommendations and the WHO declaration of palliative care as a human right,7 specialty palliative care services and resources for people with cancer are unevenly distributed and tend to be concentrated in resource-rich urban areas around the globe.3,5,8,9 This results in limited and sometimes absent access to palliative care in rural and remote areas, which are home to half of the world’s population and covers 80% or more of most countries’ landmasses.10 This disparity is even more marked in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which have the lowest palliative care availability. Fifty percent of new cancer cases occur in LMICs and carry the highest morbidity and mortality rates.3,10 Limited palliative care access for patients with cancer in rural and remote areas represents a global disparity in overall cancer care quality and is a critical public health issue.3,5,8,9,11

Although palliative care meta-analyses have demonstrated improved patient quality of life, symptom relief, depression, caregiver burden, and, in some cases, survival,12 geographical, socioeconomic, and cultural differences create barriers to implementing effective palliative care services in rural and remote areas.1,5,6,13 Indeed, few high-quality palliative care randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have focused on rural populations. However, the answer to improving rural palliative care is not simply to increase the number of rural-focused RCTs because this does not address the issue that rural and remote areas often lack basic health and cancer care services.14 Thus, a more comprehensive solution is needed and must include initiatives that address basic health policy, health care delivery, regulations that restrict appropriate opioid availability and prescription, and public and health professional education. These strategies need to be matched with measures to shift societal attitudes to recognize the value of palliative care well before the end of life.1,3,5,6,13 This review synthesizes findings from studies and systematic reviews that examined palliative care delivery, challenges, and innovations in rural and remote cancer populations.

PALLIATIVE CARE INTERVENTIONS TESTED IN RURAL SETTINGS

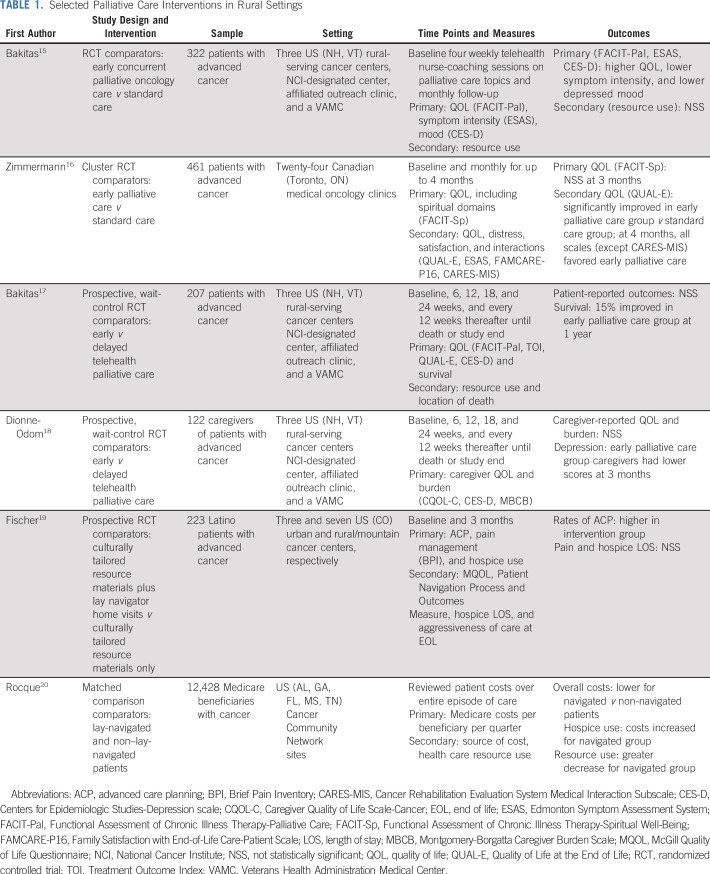

Table 1 lists six intervention studies that used a variety of designs to evaluate palliative care interventions designed specifically for rural settings. Bakitas et al15 used telehealth in two RCTs to test early palliative care in a rural-serving National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center. The first trial, ENABLE II (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends), compared early concurrent palliative oncology care in a rural comprehensive cancer center, affiliated clinics, and a Veterans Health Administration Medical Center. The patient intervention included an in-person palliative care consultation followed by four weekly telehealth coaching sessions by a nurse on palliative care topics (ie, problem solving, symptom assessment and management, communication, and advance care planning) and monthly follow-up. The intervention group had improved quality of life and mood with trends of improved symptoms and survival.15 A follow-up RCT, ENABLE III, used a prospective wait-control (also called fast-track design)21 with additional patient sessions and separate caregiver sessions.17 Although patient participants did not have statistically different patient-reported outcomes, survival at 1 year favored the early group (63% v 48%).17 The authors reported that contamination of the delayed group (more than 50% of participants received oncologist-requested palliative care before the 3-month delay) may have explained the lack of between-group differences in patient-reported outcomes.17 In the ENABLE III caregiver intervention, which similarly comprised three weekly nurse coach–delivered telehealth sessions, monthly follow-up, and a bereavement call, Dionne-Odom et al18 found that caregivers in the early group had lower depression and stress burden scores at 3 months after random assignment.

TABLE 1.

Selected Palliative Care Interventions in Rural Settings

Zimmermann et al16 conducted a cluster RCT in 461 patients across 24 rural-serving Canadian medical oncology clinics to compare early palliative care with standard oncology care. The palliative care intervention included in-clinic consultation, telephone follow-up and 24-hour telephone support, inpatient management, and home nursing and palliative care consultation as needed. Patients’ quality of life did not show improvement at 3 months (primary outcome) but did at 4 months. Patient satisfaction improved in the intervention group and decreased in the standard care group.16

With a focus on the importance of increasing access to palliative care for ethnic minorities, Fischer et al19 conducted the Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) RCT in rural and urban Colorado community clinics and a safety-net cancer center enrolling self-identified Latinos who were being treated for advanced cancer. All patients received a culturally tailored packet of written information about palliative care, and the intervention patients received at least five home visits from a culturally concordant patient navigator. The patient navigators facilitated primary palliative care conversations and delivery between the patients and their physicians. The intervention increased advanced care planning and improved physical symptoms; however, pain management, hospice use, and overall quality of life did not differ between groups.19

Rocque et al20 conducted a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–funded case control study (N = 12,428) of a lay navigation program designed to improve palliative and survivorship care access in 12 rural-serving cancer practices across five southern US states.22 In this study, high-risk patients with cancer (Medicare population older than 64 years of age) received services from a community-based lay navigator (n = 6,214) with specialized training in palliative and survivorship care. Compared with propensity-matched, non-navigated patients (n = 6,214), those who received navigation services had lower Medicare costs resulting from fewer emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit admissions.22

SELECTED BARRIERS AND CONSEQUENCES OF LIMITED PALLIATIVE CARE ACCESS IN RURAL SETTINGS

Even though the United States, Canada, and Australia have the most well-developed palliative care services globally,8 rural areas of these countries still face persistent barriers and consequences of limited access to palliative care services. For example, a US study examined provider-perceived barriers in accessing palliative care services for rural patients with cancer served by National Cancer Institute–designated academic cancer centers. Notable barriers included fragmented services, unclear referral pathways and triggers, demand that exceeded available practitioners, and insufficient or inadequate patient and oncology provider education.

In a Canadian population-based study,23 consequences of limited rural palliative care access revealed that palliative care use among rural decedents was less common than in urban decedents, and those who lived at greater distances from a palliative care program were more likely to die in a hospital. Although many rural residents die in a hospital, a review conducted in 20 countries24 revealed that 50% of rural patients expressed a preference for dying at home. A South Australian population-based survey of bereaved caregivers (n = 23,588)25 found similar levels of unmet palliative care needs in both rural and urban cancer respondents; however, rural caregivers had lower levels of support and often had to rely on friends rather than first-degree relatives for assistance in providing hands-on end-of-life care. Hence, consequences of limited palliative care access in large population-based studies revealed barriers to referral, inadequate provider education, patients dying in a hospital rather than at home (their preferred location), and gaps in family caregiver support.

INNOVATIONS TO SUPPORT RURAL FAMILY CAREGIVERS

Rural family caregivers have special challenges and are at high risk for isolation in providing care to loved ones with a serious illness. Two studies exemplify different methods that have been used to address families’ needs for self-sufficiency and empowerment. A study conducted in rural India assessed the feasibility of a caregiver support intervention (n = 30) to manage acute cancer-related symptoms (pain, dyspnea, restlessness, and cough) in the home.26 The intervention consisted of a prepackaged symptom medication kit, one-on-one training sessions, and written materials on medication use. The training and kit were low cost, feasible, positively received, and used appropriately by caregivers, and importantly, patients’ hospital visits for acute symptoms decreased by 80%.26

A study in 11 southern US rural-serving cancer centers examined patient, caregiver, and lay health care navigator perspectives on tailoring an established telehealth intervention to be delivered by a lay navigator, rather than a specially trained nurse, to serve the needs of rural caregivers of patients with advanced cancer.27 Participants recommended specific content modifications that would address their individualized needs, such as spirituality and religion (but not making it an overall focus) and maintaining telehealth delivery (but adding some in-person contact). Although telehealth has been recommended to overcome palliative care access issues, these participants expressed concern about the use of Internet-based technology, in addition to phone counseling, because of poor connectivity in rural areas. Lay navigators expressed the need for specific training in palliative care practices, but some also expressed doubt about how to incorporate palliative care content into their already-busy practice.27

NURSES AND CARE COORDINATORS PLAY A PROMINENT ROLE IN PROVIDING RURAL PALLIATIVE CARE

Numerous studies evaluated the use of nurses and care coordination approaches to meet the needs of rural palliative care patients.28-33 For example, in Norway, general district nurses provided palliative care services to patients with advanced cancer in their homes. Patients28 and their family caregivers29 attributed this service as the reason they were able to stay in their homes rather than leave their community to receive palliative services. However, at times their individual preferences could not be met because of restrictive agency policies. For example, patients believed they had little input about when they wanted to receive care versus when the nurse could be there and reported that some nurses’ skills relative to psychosocial care and communication were limited.28,29 Hence, the therapeutic value of being in a familiar setting (home) to some degree depended on the level of person-centered expertise that home care nurses could provide to their patients.

Nurse coordinators and navigators also are able to overcome the challenges of continuity of care when rural palliative care patients move across settings. For example, in an Australian home-based palliative care program, nurses provide care continuity when rural patients’ need to transition from community to hospital-based palliative care.30 In this program, families’ have reported excellent communication about the patients’ needs and care routines between the home care providers and the hospital care providers. Similarly, a rural Canadian home-based early palliative care support program for rural older adults with advanced chronic illness and their family members uses nurse-led navigation services to ensure care continuity.34 Patients in this program have reported high satisfaction with care, and health care utilization measures have demonstrated minimal and appropriate use.34

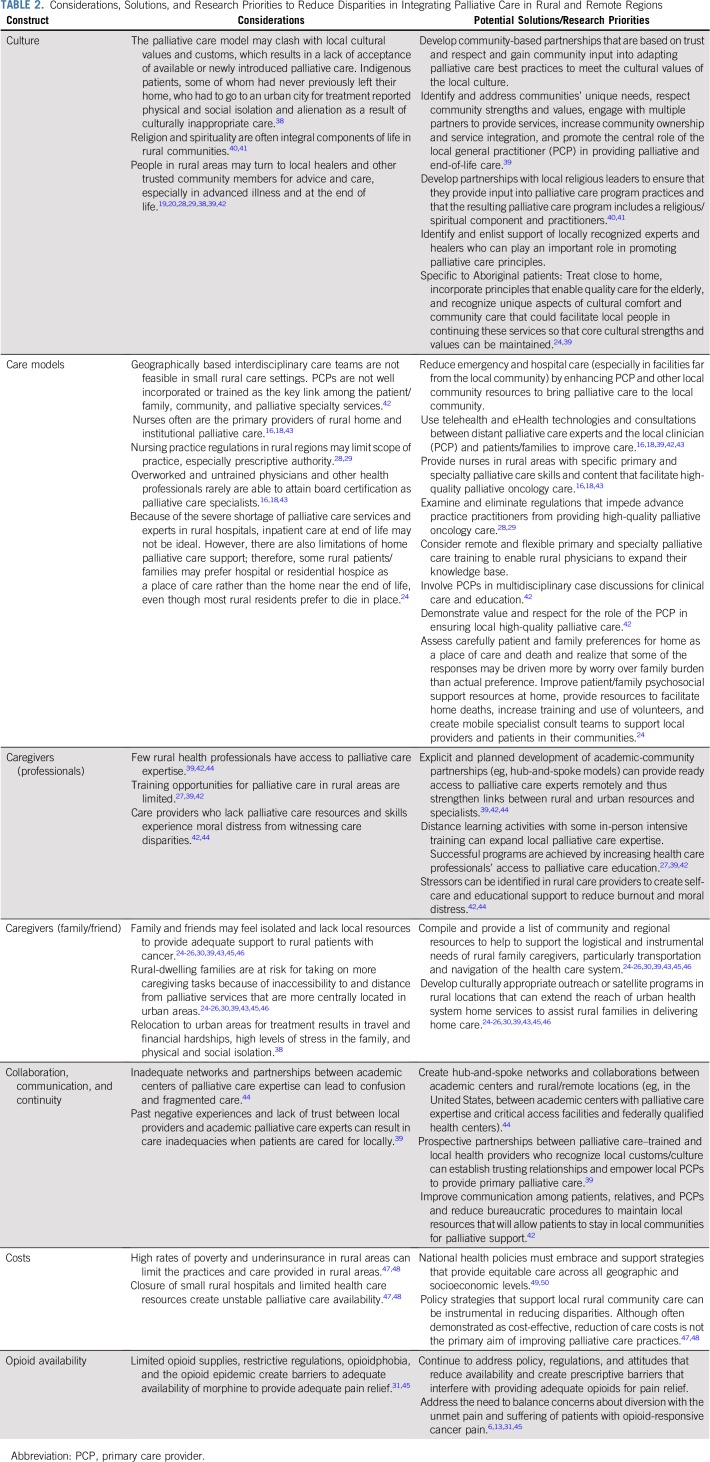

RURAL AND REMOTE PALLIATIVE CARE CONSIDERATIONS, STRATEGIES, AND RESEARCH PRIORITIES

Acclaimed anthropologist Margaret Mead is quoted as stating, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”35 This sentiment is echoed throughout rural and remote palliative care literature, which often describes small groups of dedicated investigators, clinicians, and educators who have attempted to improve the global landscape of palliative care for rural patients with cancer. Rural palliative care studies and projects are diverse; they illustrate the promise and prevalent gaps in providing palliative care in rural and remote areas. Although these studies may conjure images of pioneers blazing a new frontier, there are also prominent cries of despair from patients and providers who are suffering, often in isolation, because of a lack of access to even the most basic resources, like oral opioids.36 Therefore, although these small, thoughtful groups of palliative pioneers are making strides, a parallel effort at the highest levels of academic thinking, publishing, policy, and research also must join the effort.3,5,9,37 Table 2 lists seven selected areas of consideration raised by the literature and strategies that have been implemented or represent promising areas for future research.

TABLE 2.

Considerations, Solutions, and Research Priorities to Reduce Disparities in Integrating Palliative Care in Rural and Remote Regions

CULTURE

The importance of recognizing the unique aspects of rural culture in promoting successful palliative care programs cannot be overstated. Culture affects all aspects of a serious illness,51-55 including illness perception, meaning of suffering, method of receiving information about prognosis, end-of-life care, circumstances/location of death, and mourning. US palliative and end-of-life care services and programs often are based on Western, middle-class, Christian values—approaches that may not be effective for those who do not possess those characteristics.40,41 In general, successful palliative care programs are those that attempt to understand and incorporate local rural citizens’ cultural beliefs and values.38,39,42

In Australia, where governmental policy recommends that palliative care be accessible to all within the local community, researchers who investigate palliative care for rural indigenous Aboriginal populations have found patterns of poor local services, but more recently, promising strides are being made to address cultural issues. A review of 13 studies of Aboriginal patients with life-limiting illness who received palliative care in rural and remote areas of Australia38 found that despite attempts to provide palliative care services, the culturally specific needs of indigenous Australians who receive palliative care were not fully addressed. Specifically, the relocation of indigenous people to urban areas for treatment resulted in financial and emotional hardship, which resulted in preferences to stay at home, with family members providing care. Aboriginal patients who received care in urban areas reported alienation from their culture, which resulted in physical and social isolation.

A subsequent review identified seven key principles that are leading to improvements in palliative care for indigenous Australian populations: equity (equal access), respect of patients’ choices, acknowledgment and consideration of the historical context of colonization and its impact on the lives of indigenous people and empathy while providing care, seamless care between community-based and academic health care professionals, emphasis on living rather than on dying, respect toward cultural practices and beliefs, and humane care focused on quality of life and patient choice.56 Although developed for the Aboriginal population, these principles are broadly applicable to other rural communities.

Until recently, limited professional and public attention was paid to the unique challenges of providing high-quality palliative care in rural and remote regions. Indeed, although the WHO identified pain and palliative care as a global human right as early as 1990, most palliative and end-of-life care guidelines57-59 have offered few suggestions on how to apply these guidelines to rural or remote areas.2,58-60 A number of promising trends indicate that this is changing. For example, the revised fourth edition of the National Consensus Guidelines on Quality Palliative Care now highlights the importance of recognizing diversity and integrating culture into care.6 Other progress has resulted from leadership and advocacy through organizations like the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, an international, nongovernmental organization established in 2008 devoted to providing universal access to affordable hospice and palliative care.9 Another major stride was the publication of the Global Atlas of Palliative Care,8 which identified that approximately 30 million people died of diseases while in need of palliative care (approximately 8 million of these had cancer) and that current systems/providers were meeting only approximately 14% of the need.

MATCHING CARE TO RESOURCES

Although a number of studies have shown the effectiveness of a traditional palliative care specialty clinic and interdisciplinary team approach, such care models may not be feasible in rural and remote areas. In recognition of this, ASCO developed a resource-stratified guideline to provide recommendations to clinicians and policymakers for resource-poor LMICs, most of which have large rural and remote areas.1,6,60 This guideline identifies seven recommendations suitable to areas with limited resources, including innovative palliative care models, timing, workforce, knowledge and skills, nurses’ role in pain management, spiritual care, social work/counseling, and opioid availability.60

Care models that leverage the use of local care providers and promote local palliative care champions have demonstrated success in achieving positive outcomes. For example, general practitioners (also called primary care providers [PCPs]) in rural North America, Australia, and the Netherlands42 who received primary palliative care training were effective in reducing emergency room visits and hospital admissions for patients with serious illnesses. Although such models have enhanced PCPs’ sense of being valued members of the team, challenges to widespread adoption of PCP-delivered palliative care exist.61-64 Such barriers include lack of funding to cover palliative care services, insufficient PCP palliative care training opportunities, technology difficulties to providing care over large geographic areas, lack of PCP expertise in palliative and home health technologies, and PCP perception that providing palliative care in addition to usual care for patients with seriously illnesses is burdensome.61-64

EDUCATING AND EMPOWERING PROFESSIONAL AND FAMILY/FRIEND CAREGIVERS

Palliative care workforce shortages exist and are predicted to worsen because demand already has outpaced the supply of palliative care specialists.65 Few rural physicians receive support for the fellowship training needed for palliative care board certification, so developing creative distance learning experiences for physicians and further developing a multidisciplinary team and lay workforce to deliver specialty and primary palliative care services are essential. This approach is featured prominently in the rural palliative care literature. Primary palliative care training to local oncology and community-based nurses and lay health workers is a common solution to closing the care gap in rural and remote palliative care.16-20 Indeed, a multidisciplinary approach can affect quality of life, communication, and resource use in many rural and remote areas.15-20 However, initial and ongoing educational and material support for physicians, nurses, and other health workers is needed. A key aspect of palliative care training is ensuring that patients’ cultural values and preferences are assessed and factor prominently into care plan development.66

Three programs are notable for providing successful outreach to enhance palliative care expertise of rural clinicians. First, Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Outcomes), which is based in New Mexico, has established sites in rural Northern Ireland, Uruguay, India, California, and Alaska. ECHO uses innovative, technology-enabled models to foster and sustain local practice communities by bringing together primary care clinicians with interdisciplinary specialist teams for ongoing case-based learning, mentoring, and sharing of best practices.67

Second, the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium is an educational initiative68,69 begun in 2000 that has provided courses, developed curricula, and hosted regional training sessions for nurses and others in all 50 US states and 99 international countries.70 Finally, the third program, under the auspices of the Open Society Foundation’s International Palliative Care Initiative, has addressed the globalization of palliative care expertise, training,66 and policy49,71-73 through a combination of grassroots and elite strategies. Keys to success and sustainability of these programs have included enlisting local partners and tailoring educational content and care practices to unique and individual community needs. Enlistment of the skills of various levels of community members is essential in educational endeavors and program management.39,42

Many unique and complex challenges exist in educating and supporting rural family caregivers,19,26,27,30,34,74 who often provide an average of 8 hours of support per day to patients with advanced cancer.75 Much of the research that involves rural cancer caregivers is descriptive and shows that although close-knit rural communities often provide informal emotional and social support, other types of social support are lacking, particularly tangible instrumental support, such as childcare, financial, housekeeping, and transportation. Consistent with population-based reports of rural health,76 many rural residents have fewer financial resources, health and social services, and transportation options than their urban counterparts. Because of longer distances between their rural home and needed urban-based care and services, rural caregivers often make significant alterations to their daily routines to accommodate the transportation needs of patients. Such accommodations can create strain in fulfilling their other obligations, such as employment and other dependent care responsibilities (eg, children). Longer distances also interfere with the delivery of professional services to the home, which when limited, shifts the burden of meeting patients’ needs to the family. Few initiatives or interventions were identified that were specifically tailored to rural cancer caregivers.

COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, AND CONTINUITY

Although not a problem that is exclusive to rural and remote areas, maintenance of collaborations, communications, and continuity across settings can be exacerbated by distance and lack of resources in rural areas. However, some specific strategies that can leverage the strengths of rural settings to improve palliative and end-of-life care have been identified.39 For example, successful models have been created by identifying and addressing local communities’ unique needs and strengths, enhancing community ownership, and promoting the central role of the PCP in providing care. Such models provide health care professionals with access to specialized training, strengthen ties between rural and urban resources, improve psychosocial support for family caregivers, provide resources for home deaths, train volunteers as care providers, and create mobile specialist consult teams to support local providers and patients. In Aboriginal patients, successful models have been developed that treat these patients in their communities in a culturally appropriate manner; an important strength is the enlistment of local community members to run and manage the services.39

Although distances create collaboration and communication challenges, there are multiple examples of how with concerted efforts, high-quality palliative care can be provided across the rural-urban continuum. For example, in Australia, investigators identified communication silos between home and hospital and designed a care model in which a nurse member of the home care team remains part of the care team when the patient needs to be hospitalized.30 Caregiver interviews conveyed that after the program was implemented, caregivers were highly satisfied with care and communication.30

COSTS

Because palliative care often is associated with lower costs in patients with serious illness,77 improvement of rural palliative care resources may result in lower health care costs. However, examination of cost issues in rural areas is complex. Studies have revealed that rural patients tend to use acute care (emergency and inpatient services) at high rates when local, home, and community palliative care services are limited. For example, a prospective longitudinal, Canadian study compared palliative care costs (including public health care system, family, and nonprofit organizations) in rural and urban decedents’ last 6 months of life.47 Compared with urban decedents, rural decedents had fewer people providing care, were less likely to receive home palliative care, and had 16.4% higher overall care costs. The later was related to higher emergency department visits, inpatient hospital use and length of stay, and more equipment/assistive aids and medications. Rural and urban families paid a comparable overall percentage of the care, but the rural families’ expenses were 43.7% higher than the urban families. Rural caregivers also had more lost time from work and higher out-of-pocket and transportation costs.47 Hence, evaluation of care costs in rural locations must consider many factors, especially family care costs, when evaluating palliative care delivery.

OPIOID AVAILABILITY

Availability and proper prescription of opioids for pain relief is a fundamental component of providing adequate palliative care, and this problem cannot be overcome by specialized training.5,9,13 For nearly three decades, the WHO has stated that relief of pain through opioid availability and palliative care is a human right and a standard of high-quality cancer care. Although advances have been made in developed countries, LMICs still lag.13 For example, in Tanzania, palliative care patients treated by a mobile team that traveled to 13 rural community hospital regions and treated patients with cancer and pain showed improved Palliative Outcomes Scale scores; however, these palliative care nurses, who were trained in morphine administration, experienced severe psychological distress from their inability to provide morphine to patients in need.45 One nurse’s poignant quote expresses how distressing the care disparities were:

The challenge was, if only in our institutions’ morphine would be available, in order that for patients like her with strong pain they might get some relief….Truly, I felt very badly; terrible. I kept thinking that there was medicine just there [at another hospital]…it really hurt me. If only this woman had lived…near a place…where oral morphine is available without severe restriction.45(pE6)

This distress is avoidable as evidenced by program evaluation outcomes in an established five-hospital system in northern India,31 which compared palliative services using the Indian Minimum Standards Tool for Palliative Care and found that the two hospitals that had morphine availability were more likely to meet the tool’s standards.31 Hence, demonstration of palliative care expertise and training must be coupled with material support for pharmacologic and other strategies so that the full spectrum of palliative care can be delivered.

ISSUES IN CONDUCTING PALLIATIVE CARE RESEARCH IN RURAL AND REMOTE AREAS

Reviews of rural and remote palliative care integration, especially in LMICs, identified pervasive care gaps and few efficacy trials.78 In many rural palliative care studies, samples sizes are small, and in the case of qualitative studies or single-program evaluations, results are not widely generalizable. In addition, notable imbalances exist in study quality and rigor between those conducted in high-income countries and LMICs. Many studies from LMICs, which represent the highest proportion of rural and remote regions, do not appear in high-impact, widely read journals, likely because of lack of study rigor.

A lack of RCTs in rural areas should not be surprising for two reasons. First, funding for palliative care is limited, and those who can compete are generally from urban academic centers. Second, and possibly more importantly, rural and remote locales with small populations and unique cultures do not lend themselves to the framework of a large RCT. Hence, program evaluation, mixed methods, and qualitative designs are prominent among rural palliative care study reports.29-31,45

Other methods such as community-based participatory research (CBPR), in which a true partnership is formed with the community and results in strong community buy-in and support, has been shown to be particularly effective in reducing health disparities.79 In CBPR, community advisory groups partner with researchers to guide the research question and methods by providing input into the cultural and local aspects of care that the local community will support. Of note, CBPR also can highlight the barriers and facilitators that will help any new program to become established.

Another important consideration in conducting research or evaluating rural palliative care practices is defining the most important measures of success. Certainly, traditional patient-reported outcomes, such as quality of life and symptoms, are important, but equally relevant for rural communities are program reach, the ability of the program to allow patients to remain in the local community, a reduction of the burden of transportation, and a decrease in patients’ sense of dislocation when they need to receive care away from their rural home. Australian investigators have been leading the way in working with local indigenous populations to tailor palliative care practices to cultural and rural norms.32,38,39,80

In conclusion, the scaling and spreading of palliative care to rural and remote areas to meet the needs of the global population of people with cancer and their family caregivers must consider ethnic, cultural, socioeconomic, and access to equivalent care. This article describes the problems and promise of providing palliative care in rural and remote areas. Although it is appropriate to debate questions of palliative care study design, validity of instruments, appropriate timing, number of visits, and mechanisms as well as how to balance appropriate opioid prescription with the opioid epidemic, we also must consider that much of our current research provides limited direction for almost half of the world’s cancer population who are not receiving high-quality palliative care. Therefore, to ensure the goal of providing palliative care for everyone everywhere, we must be sure to include patients with cancer and family members in rural and remote areas whose voices are rarely heard.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank University of Alabama at Birmingham research librarian Rebecca Billings for coordinating the literature search.

Footnotes

Supported by grants NR013665-01A1 (M.B.) and NR017181 (M.B. and R.E.), Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute grants PLC-1609-36381 (M.B. and R.E.) and PLC-1609-36714 (M.B.), and National Institute of Nursing Research grant R00NR015903 (J.N.D.-O.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Marie Bakitas, Richard Taylor, Ronit Elk

Collection and assembly of data: Marie Bakitas, Kristen Allen Watts, Emily Malone, Susan McCammon

Data analysis and interpretation: Marie Bakitas, J. Nicholas Dionne-Odom, Richard Taylor, Ronit Elk

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Forging a New Frontier: Providing Palliative Care to People With Cancer in Rural and Remote Areas

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jco/site/ifc.

Rodney Tucker

Speakers’ Bureau: Studer Group/Huron

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carlson RW, Larsen JK, McClure J, et al. International adaptations of NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:643–648. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannon B, Zimmermann C, Knaul FM, et al. Provision of palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: Overcoming obstacles for effective treatment delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:62–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:356–376. doi: 10.3322/caac.21490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board of Health Care Services; et al: Cancer Care in Low-Resource Areas: Cancer Treatment, Palliative Care, and Survivorship Care: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2017. [PubMed]

- 6.Swarm RA, Dans M. NCCN frameworks for resource stratification of NCCN Guidelines: Adult cancer pain and palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:628–631. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization: Palliative care, 2018. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

- 8. Connor SR, Bermedo MCS: Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. London, UK, Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor SR, Gwyther E. The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:S112–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Cancer Society: Global Cancer Facts & Figures (ed 3). Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, et al. Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology (Williston Park) 2015;29:633–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:2104–2114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pettus K, De Lima L, Maurer M, et al. Ensuring and restoring balance on access to controlled substances for medical and scientific purposes: Joint statement from palliative care organizations. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2018;32:124–128. doi: 10.1080/15360288.2018.1488792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391–1454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438–1445. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. Family caregiver depressive symptom and grief outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer SM, Kline DM, Min SJ, et al. Apoyo con Cariño: Strategies to promote recruiting, enrolling, and retaining Latinos in a cancer clinical trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1392–1399. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al. Resource use and Medicare costs during lay navigation for geriatric patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:817–825. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farquhar M, Higginson IJ, Booth S. Fast-track trials in palliative care: An alternative randomized controlled trial design. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:213. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rocque GB, Partridge EE, Pisu M, et al. The Patient Care Connect Program: Transforming health care through lay navigation. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e633–e642. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.008896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavergne MR, Lethbridge L, Johnston G, et al. Examining palliative care program use and place of death in rural and urban contexts: A Canadian population-based study using linked data. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rainsford S, MacLeod RD, Glasgow NJ. Place of death in rural palliative care: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30:745–763. doi: 10.1177/0269216316628779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns CM, Dal Grande E, Tieman J, et al. Who provides care for people dying of cancer? A comparison of a rural and metropolitan cohort in a South Australian bereaved population study. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23:24–31. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chellappan S, Ezhilarasu P, Gnanadurai A, et al. Can symptom relief be provided in the home to palliative care cancer patients by the primary caregivers? An Indian study. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37:E40–E47. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dionne-Odom JN, Taylor R, Rocque G, et al. Adapting an early palliative care intervention to family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer in the rural deep south: A qualitative formative evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1519–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devik SA, Hellzen O, Enmarker I. “Picking up the pieces” - Meanings of receiving home nursing care when being old and living with advanced cancer in a rural area. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2015;10:28382. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v10.28382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Devik SA, Hellzen O, Enmarker I. Bereaved family members’ perspectives on suffering among older rural cancer patients in palliative home nursing care: A qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) [epub ahead of print on November 17, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Hatcher I, Harms L, Walker B, et al. Rural palliative care transitions from home to hospital: Carers’ experiences. Aust J Rural Health. 2014;22:160–164. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munday DF, Haraldsdottir E, Manak M, et al. Rural palliative care in North India: Rapid evaluation of a program using a realist mixed method approach. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:3–8. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_139_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Platt V, O’Connor K, Coleman R. Improving regional and rural cancer services in Western Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23:32–39. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tapela NM, Mpunga T, Hedt-Gauthier B, et al. Pursuing equity in cancer care: Implementation, challenges and preliminary findings of a public cancer referral center in rural Rwanda. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:237–245. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2256-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pesut B, Hooper B, Jacobsen M, et al. Nurse-led navigation to provide early palliative care in rural areas: A pilot study. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:37. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0211-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodreads: Margaret Mead quotes. https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/61107.Margaret_Mead.

- 36.Lynch S. Hospice and palliative care access issues in rural areas. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30:172–177. doi: 10.1177/1049909112444592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer DD, Winters CA. Palliative care in critical rural settings. Crit Care Nurse. 2016;36:72–78. doi: 10.4037/ccn2016732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansson M, Dixon K, Hatcher D. The palliative care experiences of adults living in regional and remote areas of Australia: A literature review. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53:94–104. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1268063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nancarrow SA, Roots A, Grace S, et al. Models of care involving district hospitals: A rapid review to inform the Australian rural and remote context. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39:494–507. doi: 10.1071/AH14137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krakauer EL, Crenner C, Fox K. Barriers to optimum end-of-life care for minority patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:182–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wicher CP, Meeker MA. What influences African American end-of-life preferences? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:28–58. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001125. Carmont SA, Mitchell G, Senior H, et al: Systematic review of the effectiveness, barriers and facilitators to general practitioner engagement with specialist secondary services in integrated palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 8:385-399, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakitas M, Dionne-Odom JN, Jackson L, et al. “There were more decisions and more options than just yes or no”: Evaluating a decision aid for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15:44–56. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keim-Malpass J, Mitchell EM, Blackhall L, et al. Evaluating stakeholder-identified barriers in accessing palliative care at an NCI-designated cancer center with a rural catchment area. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:634–637. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hartwig K, Dean M, Hartwig K, et al. Where there is no morphine: The challenge and hope of palliative care delivery in Tanzania. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2014;6:E1–E8. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v6i1.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bagcivan G, Dionne-Odom JN, Frost J, et al. What happens during early outpatient palliative care consultations for persons with newly diagnosed advanced cancer? A qualitative analysis of provider documentation. Palliat Med. 2018;32:59–68. doi: 10.1177/0269216317733381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dumont S, Jacobs P, Turcotte V, et al. Palliative care costs in Canada: A descriptive comparison of studies of urban and rural patients near end of life. Palliat Med. 2015;29:908–917. doi: 10.1177/0269216315583620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H, Qiu F, Boilesen E, et al. Rural-urban differences in costs of end-of-life care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Rural Health. 2016;32:353–362. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callaway MV, Connor SR, Foley KM. World Health Organization public health model: A roadmap for palliative care development. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:S6–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadler RA, Rosa WE. Distributive justice: An ethical priority in global palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1237–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bullock K. The influence of culture on end-of-life decision making. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2011;7:83–98. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.548048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwelunmor J, Newsome V, Airhihenbuwa CO. Framing the impact of culture on health: A systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethn Health. 2014;19:20–46. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.857768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elk R. A community-developed, culturally-based palliative care program for African American and white rural elders with a life-limiting illness: A program by the community for the community. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2017;7:36–40. doi: 10.1353/nib.2017.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cain CL, Surbone A, Elk R, et al. Culture and palliative care: Preferences, communication, meaning, and mutual decision making. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McDermott E, Selman LE. Cultural factors influencing advance care planning in progressive, incurable disease: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56:613–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shahid S, Taylor EV, Cheetham S, et al. Key features of palliative care service delivery to indigenous peoples in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: A comprehensive review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:72. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0325-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. WHO: WHO definition of palliative care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en.

- 58.Levy M, Smith T, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Palliative care version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:82–113. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine: Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osman H, Shrestha S, Temin S, et al. Palliative care in the global setting: ASCO resource-stratified practice guideline. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–24. doi: 10.1200/JGO.18.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson CE, Lizama N, Garg N, et al. Australian general practitioners’ preferences for managing the care of people diagnosed with cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:e90–e98. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carolan CM, Campbell K. General practitioners’ ‘lived experience’ of assessing psychological distress in cancer patients: An exploratory qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25:391–401. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kane P, Jasperse M, Egan R, et al. Continuity of cancer patient care in New Zealand; the general practitioner perspective. N Z Med J. 2016;129:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winthereik A, Neergaard M, Vedsted P, et al. Danish general practitioners’ self-reported competences in end-of-life care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34:420–427. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2016.1249059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, et al. Future of the palliative care workforce: Preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med. 2017;130:113–114. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhee JY, Foley K, Morrison RS, et al. Training in global palliative care within palliative medicine specialist training programs: A moral imperative. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:e2–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Arora S, Smith T, Snead J, et al: Project ECHO: An effective means of increasing palliative care capacity. Am J Manag Care 23:SP267-SP271, 2017. [PubMed]

- 68.Currie ER, McPeters SL, Mack JW. Closing the gap on pediatric palliative oncology disparities. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34:294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferrell B, Malloy P, Virani R. The End of Life Nursing Education Nursing Consortium project. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:61–69. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. American Association of Colleges of Nursing: About ELNEC, 2019. https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/About.

- 71.Callaway MV, Foley KM. The International Palliative Care Initiative. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Centeno C, Sitte T, de Lima L, et al. White paper for global palliative care advocacy: Recommendations from a PAL-LIFE Expert Advisory Group of the Pontifical Academy for Life, Vatican City. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1389–1397. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferris FD, Moore SY, Callaway MV, et al. Leadership development initiative: Growing global leaders… advancing palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:S146–S156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pesut B, Hooper BP, Robinson CA, et al. Feasibility of a rural palliative supportive service. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bolin JN, Bellamy GR, Ferdinand AO, et al. Rural Healthy People 2020: New decade, same challenges. J Rural Health. 2015;31:326–333. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.May P, Normand C, Cassel JB, et al. Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:820–829. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, et al. Systematic review of palliative care in the rural setting. Cancer Contr. 2015;22:450–464. doi: 10.1177/107327481502200411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riffin C, Kenien C, Ghesquiere A, et al. Community-based participatory research: Understanding a promising approach to addressing knowledge gaps in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2016;5:218–224. doi: 10.21037/apm.2016.05.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murphy C, Sabesan S, Steer C, et al. Oncology service initiatives and research in regional Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23:40–48. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]