Highlights

-

•

This study evaluated three outcome success thresholds.

-

•

39% met both MCID of 8.0 points and discharge score of ≤ 20 in Quick-DASH.

-

•

28% met both MCID of 16 points and discharge score of ≤ 20 in Quick-DASH.

Keywords: Minimal Clinically Important Difference, rotator cuff disorder, Quick-DASH

Abstract

Background

The choice of outcome success thresholds may influence clinical management, pay-for-performance, and assessment of value-based care.

Objective

To evaluate outcomes success thresholds in older adults using two different methods: 1) Minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) of the Quick-DASH and 2) Dichotomization of the Quick-DASH based on low disability rating at discharge

Design

An observational design (retrospective database study).

Setting

Dataset of 1109 patients with shoulder disorders.

Participants

297 older adults patients who were diagnosed with rotator cuff related shoulder disorders and were managed through physical therapy treatment.

Main outcome measures

We categorized and calculated how many patients met 8.0 and 16.0 point changes on the Quick-DASH. To evaluate outcomes success thresholds using dichotomization, patients who discharge score of ≤20 on the Quick-DASH were considered positive responders with successful outcomes.

Results

The percentage of positive responders who met the MCID thresholds for the Quick-DASH were 63.3% using MCID of 8.0 points, 39.7% using the MCID of 16.0 points, and 46.12% who met discharge score of ≤ 20 on the Quick-DASH. 39.0% met both MCID of 8.0 points and discharge score of ≤ 20 on the Quick-DASH. Only 28% met both MCID of 16.0 points and discharge score of = 20 on the Quick-DASH.

Conclusion

Three different success threshold derivations classified patients into three very different assessments of success. Quick-DASH scores of ≤ 20 represent low levels of self-report disability at discharge and can be a stable clinical option for a measure of success to capture whether a treatment results in meaningful improvement.

Introduction

Shoulder pain is among the most common musculoskeletal disorders, with a lifetime prevalence ranging from 6.7 to 67% in the general population.1 Shoulder pain is reported to result in limitations in social, work, and essential daily activities.2, 3 Rotator cuff disorders are the most common cause of shoulder pain3, 4 and frequently include degeneration of the rotator cuff musculature.4, 5 Previous studies have indicated that rotator cuff disorders have been found to increase in prevalence with age6, 7 and to persist in older people.3

Healthcare providers routinely use assessment results regarding patients status changes to monitor their prognosis and to make treatment decisions.8 Health status scales and questionnaires are unique because they provide a self-report of patients’ perspectives about their own health status.9 One of the most often used instruments for analyzing pain and disability of shoulder disorders is The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (DASH) outcome measure and its shortened version (Quick-DASH).10, 11 A recent systematic review12 outlined these questionnaires as the most studied for patients with rotator cuff disorders. The questions address daily and social activities, which patients generally find difficult to perform because of pain.13, 14 Both instruments are reliable, valid and responsive.4, 11 Beyond this, in order for these instruments to be clinically useful, they must demonstrate an ability to detect patient's perspective of change (interpretability), otherwise known as minimal clinically important difference (MCID).15 The interpretation of change scores are essential to compare the current and previous assessment results of an outcome measure.8 Thus, by definition, changes in DASH scores exceeding the MCID are clinically relevant.9

Although readily adopted into clinical practice, the MCID score has been questioned for its stability and utility.15 At present, the MCID is calculated by at least nine methods using two general methodologies-distribution-based and anchor-based.9, 12, 15, 16 Anchor-based methods are the preferred methodology (there are four methods this is used) as it is based on the patient's perception as the anchor for comparison.9, 17 Further, calculations of an MCID are mediated by various factors, such as the health condition, descriptive factors (i.e. age and level of education), the outcome being measured, its baseline score, the time between baseline and follow-up and the intervention.16, 17, 18 Thus, healthcare providers must be cautious in accepting the transferability of an MCID score across all populations with varying levels of severity.11, 15, 16 Regarding the MCID for the Quick-DASH, previous studies indicated that there is a wide variability in this measure ranging from 8.0 to 16.0 points.11, 12, 19, 20

Previous studies exploring shoulder disorders have focused on investigating the MCID in young patients (<50 years).11, 19, 20 Further investigation of the MCID for Quick-DASH is needed in older adults (≥65)21 since rotator cuff disorders are prevalent in this population.6, 7 It is also important to explore if patients who meet the MCID also self-report low disability ratings at discharge. A study such as this has merit since some countries’22 healthcare providers are incentivized through compensation (i.e. pay-for-performance program) to provide better-quality care based on outcome and/or process measures and MCID threshold values.23, 24 One of the obstacles to the success of pay-for-performance is the lack of valid and reliable information on care outcomes.24 Consequently, we aimed to evaluate outcomes success thresholds in older adults using two different mechanisms: (1) reported MCIDs of Quick-DASH and (2) dichotomization based on low disability rating at discharge. We hypothesized that our different measures of success will lead to the capture of distinctly dissimilar populations.

Methods

Reporting guidelines

This study used the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected Data (RECORD) to guide the reporting.25

Study design

The study was an observational design (retrospective database study).

Participants and setting

Participants included patients of both sexes, age ≥65 years, who were diagnosed with shoulder disorders (i.e. rotator cuff disorders) and were treated in a physical therapy clinic. These patients were extracted from a dataset of 1109 individuals with shoulder related diagnoses, who were treated from 2016 to 2017. We targeted the International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) codes consistent with rotator cuff related shoulder pain, which encompasses a spectrum of shoulder conditions including: subacromial pain (impingement) syndrome, rotator cuff tendinopathy, and symptomatic partial and full thickness rotator cuff tears.26 We targeted this subgroup of older adults (≥65) in an attempt to homogenize the shoulder diagnostic properties of the population.6, 7 All patients signed a written consent form.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University, Durham, NC, USA (Pro0092671).

Treatment

The study evaluated outcomes from patients who were treated by physical therapists from multiple clinical practices. Treatment was pragmatic and was based on each patient's impairments and presentation. Interventions were coded by Common Procedural Treatments (CPT) and the majority of individuals received exercise-only based codes (57.31% (SD = 14.60)) or manual therapy (20.42% (SD = 9.82)). Over twenty percent of individuals received passive care options (22.27% SD = 12.31)).

Descriptive variables

Patient characteristics were captured at baseline including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diagnosis, total visits, total days of care, total number of comorbidities, household income, educational status, baseline disability (measured by Quick-DASH questionnaire) and baseline health-related quality of life (physical and mental components score, measured by 12-item Veteran's RAND Health Survey).27 The VR-12 is a reliable health questionnaire developed from a modified version of Short Form Survey (SF-36).28 Higher scores of the VR-12 indicate better health status.27

Outcome measures

All patients completed the Quick-DASH questionnaire at baseline and at the end of a tailored physical therapy program. The Quick-DASH is a short version of the original DASH, developed by Beaton et al.13 in 2005, and contains 11-items, beyond an optional work and sport module.13, 14 Each item has 5 response options (no difficult, mild difficult, moderate difficult, severe difficult and unable). The overall score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 100 points (most severe disability).29, 30 Because of the shorter nature of the Quick-DASH, it may allow for expedited completion in the clinic setting.29, 31

Data sources/measurement

All data were extracted from the ATI Patient Outcomes Registry. The ATI Patient Outcomes Registry collects observational, epidemiologic, financial and clinical data that supports innovative approaches to physical therapy and provides broader awareness of patient outcomes.32

The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02285868) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the Registry of Patient Registries (2608). The de-identified data were not re-coded or manipulated and represented the raw form of findings from clinical practice. Missing values were only present in 0.71 percent of variables. Nearly 85% of cases had complete variables.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (Chicago, USA).33 To evaluate outcomes success thresholds using MCID we categorized and calculated how many patients did and did not meet a minimum of 8.0 point changes and a minimum of 16.0 point changes in Quick-DASH.11 The choice of these MCIDs was based on previous studies11, 19 which investigated MCIDs for Quick-DASH using the point on the ROC curve19 and a triangulation of distribution and anchor-based approaches.11 We selected low and high MCIDs for Quick-DASH to better explore the limits of the MCID measures. These previous studies also calculated the standard error of measurement/SEM (which links the reliability to the standard deviation of the sample)11 and the minimum detectable change/MCD, (which is considered the smallest change in score, based on the SEM).11 The Standard error of measurement (SEM) calculated from 8.0-point changes in Quick-DASH is 4.8, which corresponds with minimum detectable change (MDC) values of 11.2 percentage points.19 The SEM and MDC calculated from 16.0-point changes in Quick-DASH are 5.51 and 12.85, respectively.11

To evaluate outcomes success thresholds using dichotomization based on self-rated disability at discharge, patients who scored ≤20 on the Quick-DASH were considered positive responders to treatment with low disability. The choice of this threshold was based on previous studies, which investigated the MCID in patients with other musculoskeletal disorders.34, 35 Descriptive statistics were performed to describe all variables using univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni Hochberg correction36 and Chi square analyses. Statistical significance was initially defined as p-value <0.05. We also compared the numbers of subjects who met success in both categories using a 2 × 2 contingency table.

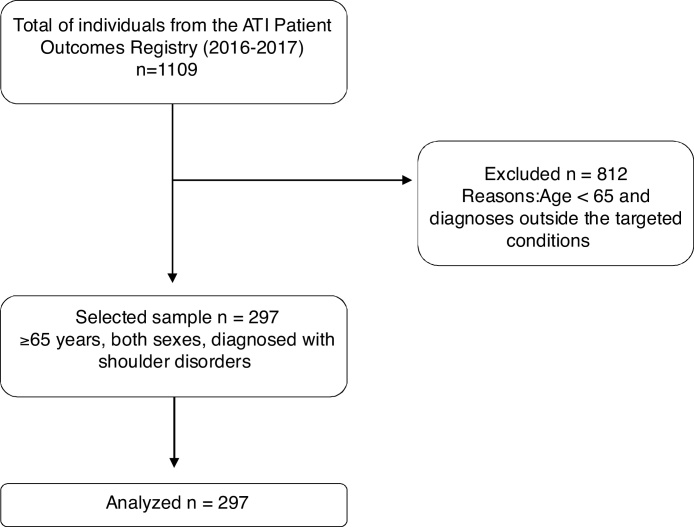

Results

From a dataset of 1109 individuals, 297 older adults with shoulder disorders who received physical therapy treatment were included (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1. Most of the study participants were women, overweight, with a mean age of 73 years (SD = 6.82). The most frequent rotator cuff disorders diagnoses identified was bursa and tendon disorders. Total comorbidities ranged from 0 to 19 (mean = 3.56; SD = 2.45); total visits ranged from 3 to 36 (mean = 14; SD = 6) and total days of care ranged from 0 to 5491 (mean = 113.68; 603.76). The baseline mean for the Quick-DASH and VR-12 scores demonstrated moderate levels of disability and health quality, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics (n = 297).

| Variables | Mean (SD)/frequency | Range or percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 73 (6.82) | 65–101 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 172 | 57.9 |

| Male | 125.0 | 42.1 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 29 (6.58) | 17.54–66.56 |

| Diagnosis (ICD-9) | ||

| Bursa and tendon disorders (726.10) | 140 | 47.1 |

| Calcifying tendinitis of shoulder (726.11) | 1 | 0.3 |

| Unspecified shoulder lesions (726.19) | 9 | 3.0 |

| Complete rupture of rotator cuff (727.61) | 55 | 18.5 |

| Rotator cuff (capsule) sprain (840.40) | 92 | 31.0 |

| Total visits | 14 (6.00) | 3–36 |

| Total days in care | 113.68 (603.76) | 0–5491 |

| Total number of comorbidities | 3.56 (2.45) | 0–19 |

| Household income (USD) | 64,052.34 (12,611.76) | 37,460.00–98,704.00 |

| Education statusa | 10.75 (3.85) | 3.76–19.07 |

| Baseline MCS of VR-12 | 42.55 (5.85) | 25.76–58.26 |

| Baseline PCS of VR-12 | 38 (5.81) | 22.60–54.04 |

| Initial Quick-DASH | 39.51 (16.81) | 16.00–88.00 |

ICD, International Diagnosis Code; USD, American dollar; MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; VR, veteran's rand; DASH, The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire. Higher scores for DASH indicates more disability. Higher scores for VR-12 indicates higher level of health.

Mean of adults>25 years of age without high school diploma per American Community Survey 2010–2014 estimates.

Table 2, Table 3 display the results of demographic characteristics across measures of success (MCID of 8.0 and 16.0 and discharge score of ≤20 on the Quick-DASH, respectively). We found significant differences in initial Quick-DASH scores and total of comorbidities (p < 0.05) among patients who met and did not meet the MCID point changes (8.0 and 16.0) on the Quick-DASH. Patients who met the MCID of 8.0- and 16.0-point change on the Quick-DASH had higher initial Quick-DASH score and had lower number of comorbidities.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics across measures of success (MCID of 8.0 points and low disability at discharge).

| Variables | Met 8.0 point change in Quick-DASH n = 188 |

Did not meet 8.0 point change in Quick-DASH n = 109 |

p value | Discharge score of ≤20 on the Quick-DASH n = 137 |

Discharge score of >20 on the Quick-DASH n = 160 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.73 (6.48) | 73.45 (6.80) | 0.38 | 72.59 (6.45) | 73.35 (7.13) | 0.33 |

| Sex | 0.31 | 0.04 | ||||

| Female | 113 | 59 | 71 | 101 | ||

| Male | 75 | 50 | 66 | 59 | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 29.05 (7.07) | 28.88 (5.67) | 0.83 | 28.83 (6.47) | 29.12 (6.76) | 0.71 |

| Diagnosis (ICD) | 0.86 | 0.55 | ||||

| Bursa and tendon disorders (726.10) | 87 | 53 | 63 | 77 | ||

| Calcifying tendinitis (726.11) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Unspecified shoulder lesions (727.19) | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Complete rupture of rotator cuff (272.61) | 34 | 21 | 22 | 33 | ||

| Rotator cuff (capsule) sprain (840.40) | 61 | 31 | 47 | 45 | ||

| Baseline MCS of VR-12 | 42.58 (5.92) | 42.50 (5.74) | 0.90 | 43.42 (4.94) | 41.81 (6.45) | <0.01 |

| Baseline PCS of VR-12 | 37.82 (5.72) | 38.28 (5.98) | 0.50 | 38.64 (5.28) | 37.43 (6.20) | 0.07 |

| Initial Quick-DASH | 41.36 (16.63) | 36.31 (16.70) | <0.01 | 31.12 (12.63) | 46.69 (16.64) | <0.01 |

| Total visits | 14.09 (5.70) | 13.95 (6.51) | 0.84 | 13.59 (5.54) | 14.42 (6.37) | 0.23 |

| Total days in care | 107.35 (603.24) | 124.67 (607.71) | 0.82 | 86.70 (507.67) | 136.45 (675.28) | 0.50 |

| Total number of comorbidities | 3.34 (2.42) | 3.93 (2.47) | 0.04 | 3.02 (1.94) | 4.01 (2.74) | <0.01 |

| Household income (USD) | 63,782.78 (12,913.92) | 64,517.46 (12,121.17) | 0.64 | 64,342.82 (13.745,99) | 63,825.17 (11,688.74) | 0.73 |

| Education status | 10.80 (3.81) | 10.68 (3.93) | 0.80 | 10.83 (3.93) | 10.70 (3.80) | 0.78 |

Categorical variables are expressed as number and continuous variables are expressed as mean (SD). ICD, International Diagnosis Code; USD, American dollar; MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; VR, veteran's rand; DASH, The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire. Higher scores for DASH indicates more disability. Higher scores for VR-12 indicates higher level of health.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics across measures of success (MCID of 16.0 points and low disability at discharge).

| Variables | Met 16.0 point change in Quick-DASH n = 118 |

Did not meet 16.0 point change in Quick-DASH n = 179 |

p value | Discharge score of ≤20 on the Quick-DASH n = 137 |

Discharge score of >20 on the Quick-DASH n = 160 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.82 (7.72) | 73.11 (6.42) | 0.73 | 72.59 (6.45) | 73.35 (7.13) | 0.33 |

| Sex | 0.11 | 0.04 | ||||

| Female | 75 | 97 | 71 | 101 | ||

| Male | 43 | 82 | 66 | 59 | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 28.82 (6.71) | 29.10 (6.50) | 0.72 | 28.83 (6.47) | 29.12 (6.76) | 0.71 |

| Diagnosis (ICD) | 0.17 | 0.55 | ||||

| Bursa and tendon disorders (726.10) | 52 | 88 | 63 | 77 | ||

| Calcifying tendinitis (726.11) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Unspecified shoulder lesions (727.19) | 1 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Complete rupture of rotator cuff (272.61) | 26 | 47 | 22 | 33 | ||

| Rotator cuff (capsule) sprain (840.40) | 38 | 69 | 47 | 45 | ||

| Baseline MCS of VR-12 | 42.09 (6.02) | 42.32 (5.74) | 0.40 | 43.42 (4.94) | 41.81 (6.45) | <0.01 |

| Baseline PCS of VR-12 | 37.38 (5.36) | 38.38 (6.07) | 0.15 | 38.64 (5.28) | 37.43 (6.20) | 0.07 |

| Initial Quick-DASH | 44.81 (16.60) | 36.01 (16.05) | <0.01 | 31.12 (12.63) | 46.69 (16.64) | <0.01 |

| Total visits | 13.59 (5.56) | 14.34 (6.28) | 0.29 | 13.59 (5.54) | 14.42 (6.37) | 0.23 |

| Total days in care | 138.56 (748.17) | 96.55 (481.88) | 0.58 | 86.70 (507.67) | 136.45 (675.28) | 0.50 |

| Total number of comorbidities | 3.05 (2.06) | 3.89 (2.63) | <0.01 | 3.02 (1.94) | 4.01 (2.74) | <0.01 |

| Household income (USD) | 64,324.00 (13,041.00) | 63,876.00 (12,362.00) | 0.77 | 64,342.82 (13.745,99) | 63,825.17 (11,688.74) | 0.73 |

| Education status | 10.85 (3.77) | 10.69 (3.91) | 0.73 | 10.83 (3.93) | 10.70 (3.80) | 0.78 |

Categorical variables are expressed as number and continuous variables are expressed as mean (SD). ICD, International Diagnosis Code; USD, American dollar; MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; VR, veteran's rand; DASH, The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire. Higher scores for DASH indicates more disability. Higher scores for VR-12 indicates higher level of health.

Four variables (sex, baseline MCS of VR-12, initial Quick-DASH and total of comorbidities) revealed significant difference (p < 0.05) between with self-reported low (≤20) versus high (>20) disability scores on the Quick-DASH. Patients who met the discharge score of ≤20 were predominantly women, had higher MCS of VR-12 (better mental health), lower initial Quick-DASH scores (lower disability) and lower number of comorbidities.

Table 4 reflect the overlap in patients meeting both definitions of success (low and high MCIDs versus low disability at discharge). From 297 patients, 116 patients (39.0%) met both MCID of 8.0 points and discharge score of ≤20 in Quick-DASH. Only 83 patients (28%) met both MCID of 16.0-point changes and discharge score of ≤20 in Quick-DASH.

Table 4.

Two by two table reflecting overlap in patients meeting both definitions of success.

| A. MCID of 8.0 point change in Quick-DASH and discharge score of ≤ 20 on the Quick-DASH | Discharge score of ≤ 20 on theQuick-DASH | Discharge score of > 20 on theQuick-DASH |

|---|---|---|

| Met 8.0 point change in Quick-DASH | 116a(39%) | 72 (24%) |

| Did not meet 8.0 point change in Quick-DASH | 21 (7%) | 88b(30%) |

| B. MCID of 16.0 point change in Quick-DASH and discharge score of ≤ 20 on the Quick-DASH | Discharge score of ≤ 20 on theQuick-DASH | Discharge score of >> 20 on theQuick-DASH |

|---|---|---|

| Met 16.0 point change in Quick-DASH | 83a(28%) | 35 (12%) |

| Did not meet 16.0 point change in Quick-DASH | 54 (18%) | 125b(42%) |

MCID, minimal clinically important difference.

Both met MCID.

Both failed to meet MCID.

Discussion

This study sought to evaluate outcome success thresholds in older adults by using MCID and dichotomization based on self-reported disability scores at discharge. We hypothesized that our various measures of success would capture distinctly dissimilar populations, and indeed that was evident. Previously published Quick-DASH thresholds for MCID were used in this study.11, 19 To better investigate the influence of a wider range in MCID values, we selected two different MCIDs (8.0 and 16.0 points for Quick-DASH). This study has importance since the way “success” is defined in a study can influence responders analyses,37 and could potentially influence reimbursement in pay for performance environments.

In our study, the percentage of positive responders who met the defined MCID thresholds were 63.3% using MCID of 8.0 points, 39.7% using the MCID of 16.0 points for the Quick-DASH, and 46.12% who met the discharge score of ≤20 on the Quick-DASH. As hypothesized, the definitions of “success” often did not overlap when comparing two different definitions. Indeed, different thresholds of success reflect different patient types and qualities. Notable significant differences in descriptive variables were present across definition comparisons. Further, when we evaluated whether the “success” definitions captured the same individuals, only 39.0%, and 27.9% were the same across our two comparisons (Table 4).

We feel that the notable differences across comparisons are even more compelling based on our method of patient selection. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain is more common in the older people.11, 19, 20 Patient age may increase the chance of having concomitant factors (e.g. degeneration, decreased vascularity, full thickness rotator cuff tears) that increase the likelihood of undergoing surgical repair and presenting re-tears following rotator cuff repair.38, 39, 40, 41, 42 We targeted individuals age 65 and older with rotator cuff specific disorders. We did so for several reasons, one being that we were keen to homogenize the patient population to a “like type” category. We feel that this subgroup from our original dataset of 1109 individuals should increase the likelihood of success measures identifying a similar patient phenotype. Nevertheless, we observed that patient-related findings dictated success grouping. We also observed that patients who have higher initial Quick-DASH scores (higher disability) and lower number of comorbidities are more likely to meet both MCID thresholds. In contrast, patients who present a better health quality, lower initial Quick-DASH scores and lower number of comorbidities were more likely to present with low disability at discharge. Indeed, previous studies have indicated that patient demographics and patient baseline status can significantly influence the MCID score.15, 43

Our results are particularly important for the healthcare providers, policy makers, and insurance providers in light of today's environment associated with financial incentive programs (i.e. pay-for-performance). Pay-for-performance has become an increasingly common central strategy in the drive to improve health care.22 This program provides financial rewards or penalties to individual/group healthcare providers or institutions according to their performance on measures of quality.44 Reimbursing based on the MCID or threshold score may mean that clinicians will cherry pick selected patients (or potentially, avoid treating them) based on baseline criteria. Selected population such as those with chronic pain/disorders often fail to improve with conventional care and are especially vulnerable to pay-for-performance caveats.23

Individual healthcare providers, group providers and institutions should be aware that determining whether or not a patient successfully responded to treatment15 based solely on a defined MCID threshold may not truly represent a patient's recovery at discharge. Further, the MCID may be less or greater (as expected) than MDC given that is calculated based on patient response-anchored method, whereas the MCD is calculated as a statistical threshold based on SEM.15, 45 Clinically, MDC alone does not provide information regarding the clinical significance of minimal amount of change that is free of random variation in measurement.45 One should especially be concerned of situations where the MCID is less than the MDC; the change associated with the MCID is not substantial enough to account for the error in the instrument. Policy makers and insurance providers should also consider and incorporate this information into healthcare pay-for-performance programs. We feel and others have reported that a discharge Quick-DASH score of ≤20 is holds face validity and represents those with low disability,34 but to our knowledge, it is not commonly used in clinical practice. Our results suggest that this measure, at a minimum, reasonably captures whether a treatment results in meaningful improvement.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine three measures of success to capture disability improvement in older adults with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disorder. Our sample size of 297 patients allows for better generalizations since it homogenized subjects into similar diagnostic categories. Our results should be viewed within the limitations of our study. Slightly over thirty individuals had baseline Quick-DASH scores that were less than 20 points, suggesting low initial disability. However, all subjects had Quick-DASH scores of 16 or greater, allowing all to theoretically meet the proposed MCID scores. Retrospective, observational registry studies can only study associations and not causality.46 In addition, we relied on multiple clinicians and researchers, for the accuracy of conduct and reporting at the time of documentation. Care varied among participants as did number of visits and follow up (3–36 visits). Pain intensity and some other psychosocial variables (e.g. anxiety, depression, catastrophizing, fear of movement) data and long-term follow up data were not available.

Conclusion

Determining whether a patient successfully responded to treatment based solely on a defined MCID threshold may not truly represent a patient's disability report at discharge. Three different measures of “success” scores identified three very different populations in older adults. Scores of ≤20 on the Quick-DASH represent low levels of self-report disability at discharge and can be a stable clinical measure of success to capture whether a treatment results in meaningful improvement.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University, Durham, NC, USA (Pro0092671).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Luime J.J., Koes B.W., Hendriksen I.J. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population: a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33(2):73–81. doi: 10.1080/03009740310004667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent K., Leboeuf-Yde C., Gagey O. Are degenerative rotator cuff disorders a cause of shoulder pain? Comparison of prevalence of degenerative rotator cuff disease to prevalence of nontraumatic shoulder pain through three systematic and critical reviews. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(5):766–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linsell L., Dawson J., Zondervan K. Prevalence and incidence of adults consulting for shoulder conditions in UK primary care; patterns of diagnosis and referral. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(2):215–221. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdermid J.C., Khadilkar L., Birmingham T.B., Athwal G.S. Validity of the QuickDASH in patients with shoulder-related disorders undergoing surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(1):25–36. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page M.J., Green S., McBain B. Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012224. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teunis T., Lubberts B., Reilly B.T., Ring D. A systematic review and pooled analysis of the prevalence of rotator cuff disease with increasing age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(12):1913–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto A., Takagishi K., Osawa T. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratford P.W., Riddle D.L. When minimal detectable change exceeds a diagnostic test-based threshold change value for an outcome measure: resolving the conflict. Phys Ther. 2012;92(10):1338–1347. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vet H.C., Terwee C.B., Ostelo R.W., Beckerman H., Knol D.L., Bouter L.M. Minimal changes in health status questionnaires: distinction between minimally detectable change and minimally important change. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy J.S., MacDermid J.C., Woodhouse L.J. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(5):623–632. doi: 10.1002/art.24396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchignoni F., Vercelli S., Giordano A., Sartorio F., Bravini E., Ferriero G. Minimal clinically important difference of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure (DASH) and its shortened version (QuickDASH) J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(1):30–39. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2014.4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St-Pierre C., Desmeules F., Dionne C.E., Fremont P., MacDermid J.C., Roy J.S. Psychometric properties of self-reported questionnaires for the evaluation of symptoms and functional limitations in individuals with rotator cuff disorders: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(2):103–122. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaton D.E., Wright J.G., Katz J.N. Upper Extremity Collaborative Group. Development of the QuickDASH: comparison of three item-reduction approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):1038–1046. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudak P.L., Amadio P.C., Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand). The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright A., Hannon J., Hegedus E.J., Kavchak A.E. Clinimetrics corner: a closer look at the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) J Man Manip Ther. 2012;20(3):160–166. doi: 10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook C.E. Clinimetrics corner: the minimal clinically important change score (MCID): a necessary pretense. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(4):E82–E83. doi: 10.1179/jmt.2008.16.4.82E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angst F., Aeschlimann A., Angst J. The minimal clinically important difference raised the significance of outcome effects above the statistical level, with methodological implications for future studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;82:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauridsen H.H., Hartvigsen J., Manniche C., Korsholm L., Grunnet-Nilsson N. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference for pain and disability instruments in low back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mintken P.E., Glynn P., Cleland J.A. Psychometric properties of the shortened disabilities of the Arm Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (QuickDASH) and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with shoulder pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Kampen D.A., Willems W.J., van Beers L.W., Castelein R.M., Scholtes V.A., Terwee C.B. Determination and comparison of the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC) of four-shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) J Orthop Surg Res. 2013;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization: Health Statistics and Information Systems. Available at:https://www.who.int/healthinfo/en/

- 22.Jha A.K., Joynt K.E., Orav E.J., Epstein A.M. The long-term effect of premier pay for performance on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1606–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1112351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shakir M., Armstrong K., Wasfy J.H. Could pay-for-performance worsen health disparities? J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):567–569. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steenhuis S., Groeneweg N., Koolman X., Portrait F. Good, better, best?. A comprehensive comparison of healthcare providers’ performance: an application to physiotherapy practices in primary care. Health Policy. 2017;121(12):1225–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benchimol E.I., Smeeth L., Guttmann A. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis J. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: assessment, management and uncertainties. Man Ther. 2016;23:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selim A.J., Rogers W., Fleishman J.A. Updated U.S. population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12) Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):43–52. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazis L.E., Lee A., Spiro A. Measurement comparisons of the medical outcomes study and veterans SF-36 health survey. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25(4):43–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.2018. The DASH Outcome Measure – Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand. Available on: URL. Year accessed Date Cited. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iordens G.I.T., Den Hartog D., Tuinebreijer W.E. Minimal important change and other measurement properties of the Oxford Elbow Score and the Quick Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder, and Hand in patients with a simple elbow dislocation; validation study alongside the multicenter FuncSiE trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e 0182557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gummesson C., Ward M.M., Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Therapy A.P. 2019. ATI Patient Outcomes Registry. Available on: URL. Year accessed Date Cited. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field A. Sage; 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostelo R.W., Deyo R.A., Stratford P. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine. 2008;33(1):90–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Roer N., Ostelo R.W., Bekkering G.E., van Tulder M.W., de Vet H.C. Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity, functional status, and general health status in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 2006;31(5):578–582. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201293.57439.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armstrong R.A. When to use the B onferroni correction. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 2014;34(5):502–508. doi: 10.1111/opo.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwind J., Learman K., O’Halloran B., Showalter C., Cook C. Different minimally important clinical difference (MCID) scores lead to different clinical prediction rules for the Oswestry disability index for the same sample of patients. J Man Manip Ther. 2013;21(2):71–78. doi: 10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson P.M., Wilson J., Dalal S., Parker R.A., Norburn P., Roy B.R. Rotator cuff repair in patients over 70 years of age: early outcomes and risk factors associated with re-tear. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(2):199–205. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B2.30246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le B.T., Wu X.L., Lam P.H., Murrell G.A. Factors predicting rotator cuff retears: an analysis of 1000 consecutive rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1134–1142. doi: 10.1177/0363546514525336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogawa K., Yoshida A., Inokuchi W., Naniwa T. Acromial spur: relationship to aging and morphologic changes in the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diebold G., Lam P., Walton J., Murrell G.A.C. Relationship between age and rotator cuff retear: a study of 1600 consecutive rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(14):1198–1205. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazarides A.L., Alentorn-Geli E., Choi J.H. Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a different disease than rotator cuff tears in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(11):1834–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y.C., Hart D.L., Stratford P.W., Mioduski J.E. Baseline dependency of minimal clinically important improvement. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):675–688. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendelson A., Kondo K., Damberg C. The effects of pay-for-performance programs on health care use, and processes of care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):341–353. doi: 10.7326/M16-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haley S.M., Fragala-Pinkham M.A. Interpreting change scores of tests and measures used in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2006;86(5):735–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tofthagen C. Threats to validity in retrospective studies. JADPRO. 2012;3(3):181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]