Abstract

This article describes the development of the Community Health clinic model for Agency in Relationships and Safer Microbicide Adherence intervention (CHARISMA), an intervention designed to address the ways in which gender norms and power differentials within relationships affect women’s ability to safely and consistently use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). CHARISMA development involved three main activities: (1) a literature review to identify appropriate evidence-based relationship dynamic scales and interventions; (2) the analysis of primary and secondary data collected from completed PrEP studies, surveys and cognitive interviews with PrEP-experienced and naïve women, and in-depth interviews with former vaginal ring trial participants and male partners; and (3) the conduct of workshops to test and refine key intervention activities prior to pilot testing. These steps are described along with the final clinic and community-based intervention, which was tested for feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Keywords: HIV prevention, microbicides, PrEP, intimate partner violence, intervention development, gender-based violence

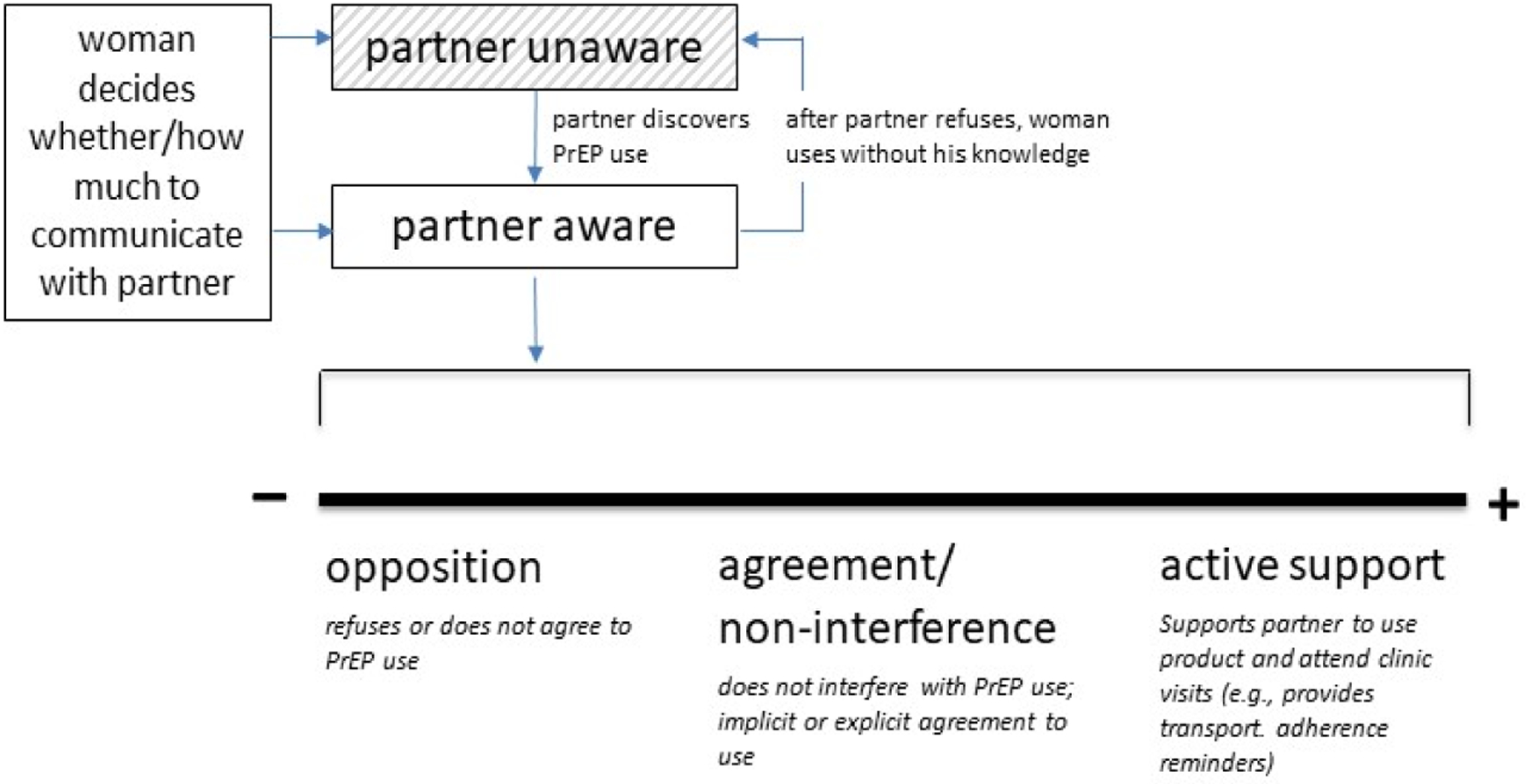

Biomedical HIV prevention strategies such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—i.e., antiretroviral-based HIV prevention including daily oral tablets (oral PrEP) and vaginal ring—were developed, in part, to give women increased control over HIV prevention. These products were meant to offer the opportunity for discreet or covert use without a partner’s knowledge or consent (Malow, Ziskind, & Jones, 2000; Minnis & Padian, 2005; Stein, Myer, & Susser, 2003). The initial notion of PrEP products being “female-controlled,” however, has been reconceptualized as “female-initiated,” as studies have shown that women’s ability and willingness to use these products is strongly influenced by male partners (Lanham et al., 2014; Montgomery et al., 2015; van der Straten et al., 2014) and gender roles and inequalities more generally (Doggett et al., 2015; Montgomery, Chidanyika, Chipato, & van der Straten, 2012). Many female participants in PrEP trials have disclosed trial participation and product use to their primary male partners (Lanham et al., 2014), yet some do not, fearing negative or even violent reactions (Corneli et al., 2015; Montgomery et al., 2015). Among male partners who are (or, have been) aware of women’s HIV prevention product use, their role has ranged from opposition to active support (Corneli et al., 2015; Doggett et al., 2015; van der Straten et al., 2014). Some women have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) related to product use (Stadler, Delany-Moretlwe, Palanee, & Rees, 2014). Indeed, social harms—defined as nonclinical adverse consequences of trial participation that result in psychosocial, social, or physical harm—that have been reported during PrEP clinical trials are often related to male partners (Palanee-Phillips et al., 2018). While the reasons for violence are diverse, some male partners feel threatened by women having access to an HIV prevention method they can use autonomously, as this shifts gender-based power and challenges the social status quo (Montgomery et al., 2015).

Consistent use is critical to PrEP effectiveness, yet product adherence has been low in some trials, especially among younger women (Ambia & Agot, 2013; Baeten, Haberer, Liu, & Sista, 1999; Marrazzo et al., 2015) who tend to have less decision-making power in relationships (Doggett et al., 2015). Evidence also exists that product adherence may be both negatively and positively influenced by male partners (Ambia & Agot, 2013; Corneli et al., 2015; Lanham et al., 2014; Mngadi et al., 2014; van der Straten et al., 2014; Ware et al., 2012). Women have reported that perceived or actual male partner resistance makes adherence more difficult (Ambia & Agot, 2013; Corneli et al., 2015; Montgomery et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2016; van der Straten et al., 2014; Woodsong & Alleman, 2008). Moreover, women experiencing IPV have lower product adherence with suggested pathways being stress and mental health challenges; lack of support for adherence; fear of negative partner reaction; partnership conflict, including partners taking products from women or forcing them to leave home; and partnership dissolution (Cabral et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2016). At the same time, adherence can be facilitated by disclosure of trial participation to male partners (Mngadi et al., 2014) and male support for trial activities (Ambia & Agot, 2013) and product use (Corneli et al., 2015; van der Straten et al., 2014). Product adherence has been highest in trials enrolling serodiscordant couples, where both partners were enrolled and counseled, leading to recommendations that adherence interventions consider partner involvement (van der Straten, Van Damme, Haberer, & Bangsberg, 2012). This recommendation is supported by evidence that some men’s resistance to the product is related to their lack of understanding of it, which can be addressed by engaging male partners and addressing their concerns directly (Montgomery et al., 2015).

In response to these recommendations, we developed the CHARISMA (Community Health Clinic Model for Agency in Relationships and Safer Microbicide Adherence) intervention. CHARISMA aims to increase women’s agency to safely and consistently use PrEP, constructively engage male partners in HIV prevention, overcome harmful gender norms that affect HIV risk, and reduce IPV. The intervention was developed to be piloted within the HOPE open-label extension study of the vaginal dapivirine ring, the first long-acting HIV prevention method found to be effective (Baeten et al., 2016; Murnane et al., 2013; Nel et al., 2016), but was designed so that it could be adapted to other PrEP product formulations. This article details the process used to adapt existing intervention models and develop the CHARISMA intervention to contribute to the evidence-base around developing locally relevant interventions to address social determinants of HIV infection.

METHODS

The CHARISMA intervention was developed through a series of primary and secondary research and intervention development activities. Activities fell into three main categories: (1) a desk review to identify appropriate evidence-based relationship dynamic scales and interventions; (2) the analysis of primary and secondary data collected from completed PrEP studies (MTN-003/015/016/020 and CAPRISA 106), surveys and cognitive interviews with women naïve to and experienced with vaginal ring trials, and in-depth interviews (IDIs) with former vaginal ring trial participants and male partners to inform the adaptation of evidence-based interventions; and (3) the conduct of workshops to test and refine key intervention activities prior to pilot testing.

FRAMEWORK AND CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Recognizing that men’s involvement in women’s PrEP use falls along a continuum, ranging from opposition to active support (Figure 1; Lanham et al., 2014), CHARISMA aimed to assess where a woman’s relationship falls on the continuum and ideally move it toward more positive male involvement, while mitigating opposition to PrEP use.

FIGURE 1.

Lanham et al.’s continuum of male partner involvement in PrEP use. Engaging male partners in women’s microbicide use: Evidence from clinical trials and implications for future research and microbicide introduction. Source: Lanham et al. (2014), Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(3 Suppl 2), 19159. Reprinted by permission.

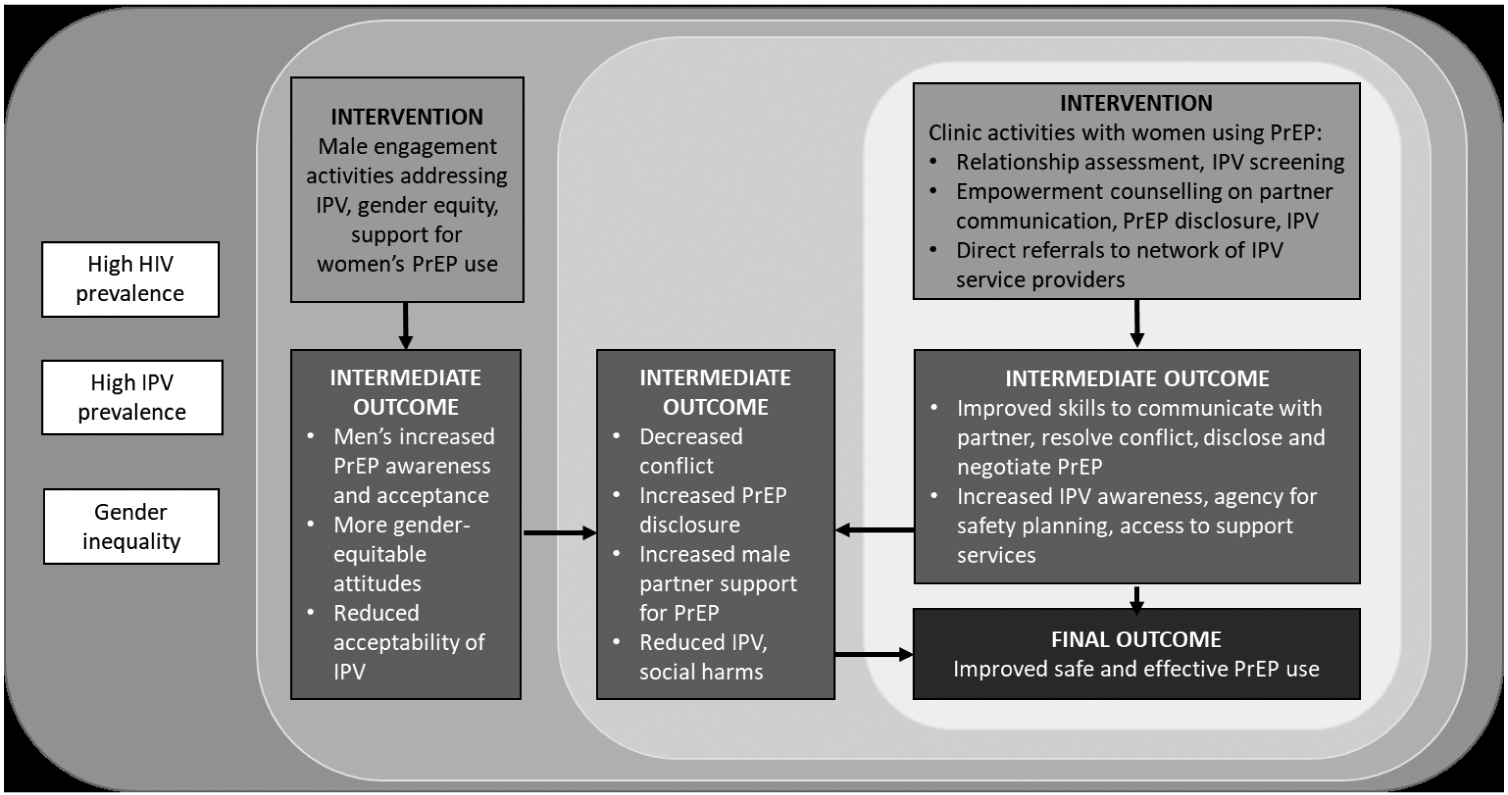

To do this, we developed a conceptual model that is grounded in the ecological model, an established theoretical base for IPV interventions that recognizes that violence is embedded in structural, community, relationship, and individual spheres (Heise, 1998). The CHARISMA conceptual model posits that an intervention that (a) works at the community, relationship, and individual levels, and (b) targets both men and women with knowledge and skills to discuss PrEP use—in a context of greater equality and safety from violence—will result in increased women’s agency to safely and consistently use HIV prevention products (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual Model of CHARISMA Intervention

INTERVENTION BASE

Aligning with the conceptual model, the intervention consists of two simultaneously implemented components directed at different levels of the ecological model and adapted from existing interventions that reduced IPV in South Africa:

A community-based component targeting men that aims to increase men’s awareness and acceptance of PrEP while promoting more gender-equitable attitudes, including decreasing their acceptance of IPV. The community component is adapted from (a) the One Man Can Campaign (Pettifor et al., 2015), which is a community mobilization intervention to challenge harmful gender norms with men, and (b) Tsima (Lippman et al., 2017), a community mobilization intervention aimed at increasing the use of HIV treatment as prevention. Both interventions were developed by Sonke Gender Justice, a South African research, training, and advocacy NGO known for its expertise on engaging men for gender equality.

A clinic-based counseling component targeting individual women using the dapivirine ring in the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN)-025 HOPE open-label extension study (Microbicide Trials Network, 2016). As part of the clinic component in CHARISMA, we developed the Healthy Relationship Assessment Tool (HEART) to assess a woman’s relationship status, screen for IPV, and guide the counselling received in that setting. The counseling aims to improve women’s skills to communicate with her partner, resolve conflict and disclose PrEP, if she desires to do so. For women in abusive relationships, the counseling aims to increase women’s awareness of IPV, increase their agency for safety planning and refer them to additional support services. The clinic-based intervention is adapted from the World Health Organization’s Safe and Sound intervention, a nurse-led counseling intervention shown to reduce IPV among antenatal care clients (Pallitto et al., 2016).

Both components work towards improving intermediate outcomes at the relationship level such as communication, conflict, and violence, which limit women’s safety to disclose and use PrEP within their partnerships.

Intervention Base for Community Component: One Man Can Campaign and Tsima.

Sonke Gender Justice (Sonke) developed One Man Can (OMC) in 2006 as a rights-based education and outreach program engaging men through a series of workshops to challenge harmful gender norms and support men and boys to take action toward gender equality and the prevention of gender-based violence and HIV (Dworkin, Hatcher, Colvin, & Peacock, 2013; van den Berg et al., 2013). Workshops were facilitated by men in groups of 15–20 with topics including gender, power, violence, HIV, healthy relationships, and taking action for social change. Workshops emphasized that men have privilege and power over women and that women’s HIV risk stems in part from these gender inequities. Individuals demonstrating leadership in the workshops were invited to become ‘community action team (CAT) members’ to use their knowledge to further educate their communities. OMC created safe spaces for men to consider and challenge traditional masculinities and gender relations. Participatory workshops (that generally have short-term impacts) were paired with community mobilization and public awareness activities that worked toward more medium and long-term impacts on gender equality in communities (Dworkin et al., 2013; Pettifor et al., 2015). Evaluations of OMC activities have shown positive effects on men’s perceptions of women’s rights and their awareness of masculinity-related barriers to HIV testing, care, and treatment (Dworkin et al., 2013; Fleming, Colvin, Peacock, & Dworkin, 2016). OMC participants have reported increased partner communication, reduced HIV risk behaviors, and reduced perpetration of IPV (Dworkin et al., 2013). A recent community mobilization randomized trial based on OMC resulted in improvements in attitudes towards gender norms, but did not result in significant changes in risk behaviors, perhaps because a more sustained and multi-level approach is needed to change behavior (Pettifor et al., 2018). The One Man Can model has been implemented in several South African provinces and in other African countries to encourage men and women to become actively involved in advocating for gender equality, preventing gender-based violence (GBV), and responding to HIV. The Tsima intervention is built on the OMC model, and has expanded the intervention to address linkage to and retention in HIV care; fear and stigma associated with HIV infection, clinic attendance, and disclosure; lack of social support; and gender norms that specifically deter men from accessing care. Tsima is currently being evaluated in a randomized control trial in Mpumalanga Province in South Africa, results expected June 2019 ( NCT02197793; Lippman et al., 2017).

Intervention Base for Clinic Component: Safe and Sound.

Safe and Sound was an intervention that was implemented with pregnant women reporting IPV in antenatal clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2016 (Pallitto et al., 2016). It was designed to reduce the recurrence of intimate partner violence and the frequency and severity of this violence. The World Health Organization (WHO), together with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medical (LSHTM) and Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Wits RHI), designed the intervention and conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate its effectiveness. Results showed that the intervention significantly reduced both physical and sexual violence by month 6 among intervention participants, as compared to controls (Garcia-Moreno & Pallitto, 2017). Safe and Sound was based on an evidence-based nurse-led empowerment counseling model (Kiely, El-Mohandes, El-KHorazaty, Blake, & Gantz, 2010; Tiwari et al., 2005), which posits that IPV is intended to disempower female partners, and counseling can help increase a woman’s sense of power over her life and help her develop partner communication and problem-solving skills to reduce violence and increase safer sex in her relationships (Dutton, 1992; McFarlane & Parker, 1994; Pallitto et al., 2016). Nurses participating in Safe and Sound received 30 hours of training on the nature of IPV and the cycle of violence; the relationship between IPV and HIV; women’s legal rights; promoting mental health; assessing women’s readiness to change; safety planning; community resources; and processing vicarious trauma (Pallitto et al., 2016). The study team had weekly meetings to debrief on counseling sessions, provide continuing support and feedback to nurses, and process emotional and mental stress. Safe and Sound included up to two sessions of empowerment counseling by research nurses. Counseling included some or all of the following elements based on a woman’s situation and needs: empathetic listening, discussing the cyclical nature of IPV, safety planning, and for some women, discussing the process of obtaining a legal protection order. Counselors also provided enhanced linkages to referral services for women experiencing violence, including counseling, shelters, legal resources, child protection, and police. The referral agencies were contacted at the beginning of the study to assess their willingness and capacity to receive referrals (Pallitto et al., 2016).

Validated Scales Serving as the Basis for Clinic-Based Screening Tool: Healthy Relationship Assessment Tool (HEART).

As a foundation for development of the HEART tool, we reviewed peer-reviewed and gray literature to identify validated scales measuring concepts of violence, social support, and agency within relationships. We included scales and/or specific items that addressed women’s relationship contexts broadly and had been used in multiple populations and/or geographic settings, especially sub-Saharan Africa. Five scales, in part or in full, provided potential items for the tool:

The Partner Violence Screen (PVS; Feldhaus et al., 1997), a three-item instrument intended for use in emergency rooms or clinic settings. The PVS measures two aspects of IPV, physical violence, and perceptions of safety.

The Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) is a 30-item partner abuse screening questionnaire that draws on items from the Conflict Tactic Scale, Measure of Wife Abuse, Inventory of Spouse Abuse, and Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory. It has four dimensions: severe combined abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and harassment (Hegarty, Bush, & Sheehan, 2005; Hegarty, Sheehan, & Schonfeld, 1999).

The Psychological Abuse Scale (Pipes & LeBov-Keeler, 1997) is a 15-item, unidirectional scale incorporating four items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 2017), ten items from the work of Hoffman (1984), and one item from Howard, Blumstein, and Schwartz (1986). It offers a definition of psychological abuse focusing on partners’ repeated use of particular tactics that cause the woman to frequently feel hurt, fearful, or badly about herself, and was intended for use among heterosexual non-married couples.

The Gender Relations Scale is based on the Sexual Relations Power Scale (SRPS) and the Gender Equitable Men (GEM) Scale to measure equity and power within intimate relationships. It has 23 items and two subscales and covers topics such as attitudes towards gender roles and expectations, decision-making around sex and reproduction, household decision-making, violence, and general communication (Stephenson, Bartel, & Rubardt, 2012).

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) assesses individuals’ perceptions of the extent to which social support is available from family, a significant other (special person), and friends. The 12-item self-report measure was developed by Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, and Farley (1988) and employs a 7-point Likert scale in which higher MSPSS scores indicate a higher availability of social support. The scale was adapted for use in Malawi to study the relationship between perceived social support, IPV, and antenatal depression (Stewart, Umar, Tomenson, & Creed, 2014).

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

A series of primary and secondary data collection and analysis activities were conducted with the aim of identifying aspects of relationships and violence in the PrEP context that should be addressed in the intervention components and the screening tool.

Secondary Data Analysis.

Secondary analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from completed microbicide studies testing products such as oral PrEP, tenofovir vaginal gel, and a dapivirine vaginal ring (e.g., MTN-003, MTN-020, and CAPRISA 106) was conducted first. Table 1 provides an overview of data sources and methods. The goal of the activity was specifically to identify how social harms (SH), IPV, and male partners’ engagement have manifested and been addressed in HIV prevention studies to inform how key messages and approaches in the OMC campaign/Tsima and Safe and Sound should be adapted for CHARISMA.

TABLE 1.

Overview of Data Sources and Analysis Methods to Inform CHARISMA Design

| Data Sources | Methodology |

|---|---|

| Secondary analysis of SH data from microbicide studies | |

| MTN-003 (Marrazzo et al., 2015), MTN-020 (Baeten et al., 2016), CAPRISA 106 (MacQueen et al., 2016) |

|

| MTN-003C (van der Straten et al., 2014), MTN-003D (van der Straten et al., 2015), MTN-020 (Montgomery et al., 2017) |

|

| Secondary analysis of male partner characteristics, participation in product use | |

| MTN-003, MTN-020, CAPRISA 106 |

|

| MTN-003C, MTN-003D, MTN-020 qualitative |

|

| Primary data collection with former trial participants, male partners, and research clinic and public healthcare clinic staff | |

| In-depth interviews |

|

| Cognitive interviews |

|

| Surveys |

|

For the quantitative analysis, we completed a comprehensive statistical analysis of partner-related SH experienced in a ring trial (MTN-020), including a tabulation of events, an examination of correlates of SH, and modeling of the impact of SH on product adherence (Palanee-Phillips et al., 2018). Additionally, we tabulated reports of SH from an oral PrEP and vaginal gel trial (MTN-003) and seroconversion and pregnancy registries (MTN-015 and MTN-016). Our analyses of male partner engagement included descriptive statistics on the prevalence of male partner engagement, including women’s disclosure of study participation and product use to their partners, partner attendance at the study clinic, and partner support or opposition to product use; examination of the correlates of male partner engagement, and when possible, analysis of the association between male partner engagement and product adherence (Sonke Gender Justice Network, 2009).

We also reviewed qualitative data from trial participants and staff on SH experienced by participants during trials and on male partner dynamics, including whether women disclosed trial participation or product use to partners and how male partners responded and influenced trial participation and product use. This review included data from qualitative studies nested within MTN-020; appended to MTN-003; or conducted after MTN-003D and CAPRISA 106 phase II and III microbicide clinical trials, totaling 244 in-depth interviews (IDIs) and 64 focus group discussions (FGDs). Data from all transcripts were systematically reviewed using either the original, relevant, study-specific codes from the studies (e.g., MALE PARTNER, POWER, VIOLENCE), or the original text responses to specific interview questions directly relevant to SH and male partner engagement. Data were summarized across studies by domain (e.g., male partner engagement and social harms).

Primary Data Collection and Analysis.

Primary data collection was conducted in Johannesburg, South Africa, the proposed site for CHARISMA implementation. Data collection included quantitative and qualitative methods, again, to both identify adaptions for One Man Can campaign/Tsima and Safe and Sound, and refine the HEART tool.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) with former MTN-020 vaginal ring trial participants and male partners were conducted to identify issues specific to the ring, and to explore experiences of SH and IPV. They were conducted with 14 women who had reported experience of partner-related harm during MTN-020 and 14 who had not, as well as with 14 male partners of former participants. Semi-structured guides were used in interviews, which were conducted by trained data collectors of the same sex as the participant in their preferred language (i.e., isiZulu, English). All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and translated into English, when applicable, for analysis. Immediately following each interview, the data collector completed a debriefing report template to summarize key data and emerging themes. Debriefing reports were uploaded into Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA), a web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data, where they were structurally coded by analysts. The analysts summarized coded content in analysis memos by themes chosen for their relevance to intervention development (e.g., relationship history, partner dynamics while using HIV prevention, relationship conflict and violence, and intervention design). Reports were completed separately for women who had reported partner related harm during the trial, those who had not, and male partners. A full description of the methods and additional results are presented elsewhere (Hartmann et al., 2019).

For the development of the HEART, we conducted 25 cognitive interviews with former trial and trial-naïve participants with and without past experience of intimate partner violence to assess ease, comprehensibility and relevance of 135 scale items. The items were drawn from the five scales described previously and also included new items to assess agency related to PrEP use. All items were administered in the form of statements to which participants could indicate a level of agreement, ranging from 1 (disagree a lot) to 6 (agree a lot). In some cases, phrasing or scoring of the original scale items were adapted so they could be administered in a consistent manner. Following this, a survey was conducted with 309 former PrEP trial and trial-naïve participants and an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify a reduced set of constructs and items that could measure social benefits and harms of PrEP use. Reliability and validity were assessed by examining hypothesized associations between emergent factors/constructs and other variables.

Workshops and Piloting Intervention Content.

The final step in developing the CHARISMA intervention was reviewing key findings from the literature review and primary and secondary data analyses, adapting content for the community and clinic components of the intervention, and piloting content in workshops with project staff and key stakeholders.

RESULTS

There were several key findings from our analyses and workshops that informed the adaptation of the One Man Can/Tsima and Safe and Sound activities as well as the refinement of the HEART screening tool for the CHARISMA intervention.

COMMUNITY-BASED INTERVENTION ADAPTATIONS

The primary findings of our analysis that were used to inform our approach to adapting One Man Can/Tsima to CHARISMA were: that having an unsupportive male partner could hinder women’s product adherence, that lack of male partner support was often linked to lack of knowledge and misconceptions on their part about the products and women’s use of them, and that it is difficult to get men to come into research clinics.

In MTN-020, women who reported experiencing partner-related social harms in the past month were 2.53 times more likely to have low adherence than women who had not reported a SH (95% CI [1.37, 4.66], p = .004; Palanee-Phillips et al., 2018). These findings confirmed the importance of male partners’ acceptance of PrEP products, the vaginal ring in particular, and support of their partners using them. Based on this finding, we developed and incorporated messages into community workshops with men about the importance of men supporting women’s right to make choices about their use of HIV prevention methods.

The primary and secondary qualitative analyses elucidated reasons for male partner opposition to product use and perpetration of social harms. These included beliefs that microbicides made sex uncomfortable (i.e., the men could feel the ring, or thought the gel made sex too wet) and concern that products encourage promiscuity by their partners.

He … abused me because of the ring, saying I was going to commit adultery.

(ASPIRE participant, MTN-020 qual, #312-40008-5)

Male partners also had concerns about products harming their partners or themselves (e.g., make them sick, sucking their blood), including interfering with conception, or they thought it was a type of witchcraft their female partners were using against them. We developed messages to address these specific concerns and beliefs such as the ring does not increase likelihood of promiscuity, as well as more general information on the product, which were built into community activities with men.

Finally, low male partner clinic attendance during MTN-020, MTN-003, and interview data from CAPRISA 106 indicated that getting male partners to come to clinics was a challenge. This was consistent with other literature from microbicide studies (Lanham et al., 2014). Partner attendance ranged from 9% to 13% across studies. This challenge was cited as being linked to multiple factors, including men’s work schedules, dislike of clinics, and fear of HIV testing. Engaging men in the broader community rather than in the clinic was identified as potentially beneficial, and trial staff suggested community outreach in locations where men are already present, such as soccer fields and taverns, which were included as sites for CHARISMA community-based activities.

Maybe ideally we do not bring [men] to [the research clinic]. Maybe go to a soccer field where they play soccer. Go to a tavern where they hang out. Go to them, rather than bringing them here.

(Research clinic staff, IDI, CAPRISA 106)

CLINIC-BASED INTERVENTION ADAPTATIONS

The key findings that informed adaptations of Safe and Sound for CHARISMA included the importance of disclosure in gaining male partner support, women’s desire for improved partner communication skills, and the need to tailor support to a woman’s individual relationship. This ultimately led to the development of three discrete counseling modules from which counselors could select for the initial counseling session: the original IPV counseling module from Safe and Sound plus disclosure and partner communication modules. Additionally, trained lay counselors were suggested instead of nurses as appropriate providers of the intervention.

In the data we analyzed, women’s disclosure of product use and study participation ranged from full to non-disclosure. Quantitative findings from MTN-020 revealed that not disclosing study participation at enrollment (1.56, 95% CI [0.72, 3.37]) was associated with experience of partner-related social harm, inclusive of study-related IPV (Palanee-Phillips et al., 2018). Qualitative findings also showed that a lack of disclosure could result in violence if male partners inadvertently discovered product use. Moreover, some women who initially tried to negotiate trial participation and product use with partners also experienced partner resistance or even social harms, such as violence. These findings led to our development of a counseling module on product disclosure skills, which specifically addressed both men’s concerns, highlighted in the previous section, as well as women’s fears of male partner reactions.

Findings from our primary data collection with women and men, however, suggested that partner communication, whether about product use or otherwise, also proved challenging for many women. Themes of mistrust and jealousy underpinned descriptions of relationship conflict, including conflict around PrEP use, as did couples’ limited ability to discuss difficult issues. Additional counseling on relationship communication and improved intimacy was explicitly desired by both women and men. Based on these findings, we developed a counseling module on partner communication to help women build skills in conflict negotiation and partner communication to enhance their ability to negotiate product use and de-escalate disagreements.

The thing is, what the most important thing in a relationship is sex, intimacy … so they must not leave that part, besides that part they also need to…with the counseling…cover the subjects of talking to each other and treating each other nicely.

(Male partner, IDI, CHARISMA formative)

The type of relationship a woman had with her partner was critical in her decision-making about disclosing product use. A woman’s marital status, whether she’s in a new or established relationship, her evaluation of her partner’s character and disposition, and the level of trust and honesty in the relationship were highlighted by women and trial staff as important considerations related to partner disclosure. For instance, not knowing her primary partner’s HIV status (aRR 1.24, 95% CI [1.07, 1.44]) was correlated with non-disclosure and being unmarried was associated with sometimes disclosing (aRR 1.29, 95% CI [1.02, 1.62]; defined as disclosure reported at some, but not all, quarterly follow-up visits) within MTN-020 (Nair et al., 2016). Qualitative accounts from participants also confirmed that if one was married or was in a relationship where you generally shared information with one another, then disclosure was desired. These findings highlighted the importance of tailoring counseling to meet the relationship needs of each woman, which informed the use of the HEART screening tool that could measure key relationship factors important to the counseling context and guide the counselor’s choice of modules (described in the next section).

Accordingly, all counselors were trained to recognize and avoid bias and tailor counselling to each individual and counseling messages were framed to respect women as authorities in their relationships.

You have to deal with each individual woman separately. The discussions you have with her have to be very different to the next woman, and it has to be very customized for her needs.

(Research clinic staff, IDI, CAPRISA 106)

Lastly, we decided to use lay counselors to deliver the counseling intervention rather than nurses, based on feedback from former MTN-020 trial participants, as well as considerations around feasibility and cost. Participants suggested that nurses might be too busy to deliver quality counseling and that women felt more at ease with lay counselors, who seemed more approachable. This belief was reinforced by women participating in our primary data collection activities.

Everyone knows the characters of the nurses. … The nurses are exhausted … Yes, they are tired. They are tired, shame … At the beginning, we never understand. But now we understand that they are exhausted. But not all of them. Others, they just answer you out of negligence.

(SH woman, IDI, CHARISMA formative)

The preference for lay counselors was simultaneously encouraged by the project Investigators and a team of project advisors convened by the funding agency who collectively felt that use of nurses for counseling in a public health setting was unsustainable.

REFINEMENT OF THE HEART SCREENING TOOL TO EVALUATE RELATIONSHIP STATUS AND GUIDE COUNSELING

The final set of items selected for the HEART tool we developed was based on results of the exploratory factor analysis, which was conducted to produce a tool that captured a range of relationship dimensions, yet would be brief to administer both in the pilot study context and outside of a research setting (i.e., requiring 10–15 minutes). This analysis produced five factors comprising of a total of 42 items. Based on item content for each factor, we identified five sub-scales representing: (1) Traditional Values, (2) Partner Support, (3) Partner Abuse and Control, (4) Partner Resistance to HIV Prevention, and (5) HIV Prevention Readiness (Table 2). We conducted analyses to assess the content and construct validity of our resulting tool. More detailed description of these analyses is presented separately (Tolley & Zissette, 2018). We then programmed the tool into tablets for lay counselors to administer to CHARISMA participants at study enrollment. Participants’ responses to each subscale are summed by the tool and then categorized as being high, medium, or low. High and low scores are those falling one standard deviation above or below the original survey scores. The scores were used to recommend counseling modules for participants. Based on discussions with CHARISMA counselors, a decision was made to offer the IPV counseling module to any participant whose score on the Partner Abuse & Control subscale fell into the medium or high category. Indeed, for the pilot phase, the project team felt it was preferable to over-prescribe these materials rather than miss offering the material to a participant who might benefit from it. If a participant reported not having disclosed product use to her partner, she was offered the counseling module on product disclosure skills. All other participants were offered the counseling module on partner communication and conflict negotiation skills. Additional details of HEART administration and counseling modules are described in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

HEART Subscales

| Factor | No. of Items, α | Example Item |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Values | 13, α = .84 | I think a woman cannot refuse to have sex with her husband. |

| Partner Support | 10, α = .81 | My partner is as committed as I am to our relationship. |

| Partner Abuse and Control | 9, α =.81 | My partner slaps, hits, kicks, or pushes me. |

| Partner Resistance | 5, α = .80 | If I asked my partner to use a condom, he would get angry. |

| HIV Prevention Readiness | 5, α = .68 | Using an HIV prevention product is the right thing to do. |

TABLE 3.

CHARISMA Intervention Components and Activities

| COMMUNITY COMPONENT | |

| Formation of Community Action Teams (CATs) |

|

| Outreach activities and topics | CAT members and intervention staff:

|

| CLINIC COMPONENT | |

| HEART screening tool |

|

| Empowerment counseling |

|

| Referral network and process |

|

| Training |

|

| Ongoing support for counselors |

|

Additionally, given the tool’s intention to guide counseling based on a woman’s current relationship and the finding from our MTN-020 secondary data analysis that indicated reporting a new partner at enrollment (aRR 2.09, 95% CI [0.87, 5.06]) was strongly correlated with experience of social harms, inclusive of study-related IPV (Palanee-Phillips et al., 2018), we decided to firstly administer the tool at enrollment and re-administer HEART at any time point when a woman reported having a new partner.

FINAL SYNTHESIS OF RESULTS THROUGH INTERACTIVE WORKSHOPS

Results of the primary and secondary analyses, described above, were synthesized and then presented or piloted in interactive workshops with stakeholders and staff.

Following a review of findings relevant to the community component of CHARISMA (e.g., those related to male partner reactions and concerns around product use and findings related to effectively reaching men), Sonke developed an activity outline for 2–3-day community workshops. They identified and developed activities that addressed men’s perceptions of HIV and their risk of infection, women’s roles in relationships and women’s agency in health seeking behaviors (particularly related to HIV prevention), and those that challenged norms that promote IPV. Staff then pilot tested the activities in a 3-day workshop in Johannesburg, South Africa. The workshop included representatives from each South African-based intervention partner organization (e.g., Sonke Gender Justice and Wits RHI), as well as community members similar to those who would be invited to join community action teams. Following each day of workshop piloting, participants gave feedback on the relevance and clarity of the topics and activities. This feedback was used to shorten the workshop content, as well as strengthen content on new HIV prevention methods, such as microbicides, and add content on safety, side effects, and efficacy.

For the clinic component of CHARISMA, a one-day workshop was conducted with staff at the Wits RHI research clinic in Hillbrow (where the clinic component would be implemented) and members of the CHARISMA intervention referral organizations. The team reviewed the findings of the secondary and primary data collection and analysis and discussed implications for CHARISMA staff training, client counseling, and clinic preparations. The team reviewed manuals of evidence-based relationship and violence-focused training and counseling and identified content to integrate into the existing Safe and Sound staff training and client counseling around IPV (Sonke Gender Justice Network, 2009). In particular, skills-based sessions on couples’ communication and conflict negotiation and HIV prevention product disclosure, as well as staff training sessions on values clarification, addressing gender bias in counseling, and treating the woman as the relationship expert were integrated into the content. The CHARISMA counseling manual and staff training manual were reviewed during another one-day workshop with CHARISMA clinic staff in Johannesburg, South Africa, and further refinements were made around items such as culturally specific signs of respect or disrespect within an intimate partnership (e.g., calling a partner by his full name when upset).

Final CHARISMA Intervention for Pilot Testing.

Table 3 outlines the key CHARISMA intervention components and activities. These include those components that were included as part of the original intervention models, those that were adapted or developed based on the results described above, as well as others that were included based on best practices for research or intervention implementation (e.g., modifying referral networks to match the geographical context of participants) or to link the intervention components (e.g., an opt-in WhatsApp group for female participants to share male outreach events). The intervention was designed to be administered within the HOPE open-label extension study of the dapivirine ring, in which women are offered the opportunity to start using the ring at the study enrollment visit, and then return for replacement rings and follow-up data collection at one month after enrollment and then quarterly thereafter (months 3, 6, 9, and 12).

DISCUSSION

This article describes the basis and development of CHARISMA, an intervention designed to increase women’s agency to consistently and safely use PrEP while reducing their risk of IPV. Previous studies have established a link between relationship dynamics and PrEP product adherence, namely that male partner acceptance and support of product use can increase adherence but male partner resistance, including IPV, negatively affects adherence (Ambia & Agot, 2013; Cabral et al., 2018; Corneli et al., 2015; Lanham et al., 2014; Mngadi et al., 2014; Montgomery et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2016; van der Straten et al., 2014; Ware et al., 2012). CHARISMA fills an important gap by holistically addressing relationship dynamics and communication skills, IPV, HIV risk, gender norms, and PrEP product use with both women and men.

CHARISMA is grounded in existing literature (Lanham et al., 2014; Montgomery et al., 2015; van der Straten et al., 2012), and findings from our primary and secondary analyses that suggest a need to increase men’s awareness, acceptance, and support for their partners’ use of PrEP; promote women’s ability to decide if, when, and how to involve male partners in PrEP use; and improve women’s ability to communicate and negotiate with their male partners. Critical to the anticipated outcomes, the intervention reaches men where they are, tailors counseling to women’s relationships and needs, and trains staff to help women assess their relationships, identify IPV, and strengthen communication skills. The CHARISMA intervention was designed for women using the dapirivine vaginal ring but was intended to be product-agnostic, such that it could easily be adapted to other women-initiated HIV prevention products, including oral PrEP.

Initial testing of the complete CHARISMA intervention in Johannesburg, South Africa, from 2016 to 2018 will provide data on the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention among participants, implementers, and other stakeholders (e.g., referral agencies), as well as preliminary evidence for its association with adherence. Participants in the clinic component were approximately 100 women enrolled at the Wits RHI site in the MTN-025/HOPE study, an open-label extension study of the dapivirine ring (Microbicide Trials Network, 2016). Women in this study were experienced dapirivine ring users, and study staff were highly trained in counseling and conducting research, making it an ideal context for this phase of testing. The community component targeted men in the communities from where the female participants came from. Finally, use of the HEART screening tool will allow for further testing of its validity and accuracy in guiding counseling decisions. Results of the pilot study are anticipated in late 2019.

Following initial pilot testing in the context of MTN-025, critical questions include whether the clinic component will be feasible to implement outside of a research context. The counseling—while conducted by lay counselors to address health systems strains on nurses—is still resource- and time-intensive. Additionally, questions remain regarding whether the clinic component will be acceptable to women with no previous HIV prevention method experience. Based on the preliminary results of the initial pilot testing, the CHARISMA intervention was adapted and is being tested for effectiveness in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with oral PrEP users.

CONCLUSION

Without intervention, the dual epidemic of IPV and HIV transmission will continue to impact women’s ability to prevent HIV, even in the age of new technologies and prevention products. CHARISMA is a community and clinic-based intervention designed to increase male partner support for female-initiated HIV prevention intervention use and improve women’s ability to use these products safely and consistently. Through extensive secondary and primary data analyses and intervention development activities, CHARISMA was designed to provide tailored interventions to both women and men targeting concerns identified in prior trials of female-initiated HIV prevention methods. Results of the CHARISMA pilot and follow-on RCT, currently in its design phase, will provide data on the acceptability and efficacy of the intervention on IPV reduction and product adherence.

REFERENCES

- Ambia J, & Agot K (2013). Barriers and facilitators of adherence in user-dependent HIV prevention trials, a systematic review. International STD Research & Reviews, 1, 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, & Sista N (2013). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: Where have we been and where are we going? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 63(Suppl 2), S122–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, … MTN-020-ASPIRE Study Team. (2016). Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 2121–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral A, Baeten JM, Ngure K, Velloza J, Odoyo J, Haberer JE, … Partners Demonstration Project Team. (2018). Intimate partner violence and self-reported pre-exposure prophylaxis interruptions among HIV-negative partners in HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 77, 154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli A, Perry B, Agot T, Ahmed K, Malamatsho F, & Van Damme L (2015). Facilitators of adherence to the study pill in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. PloS One, 10, e0125458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggett EG, Lanham M, Wilcher R, Gafos M, Karim QA, & Heise L (2015). Optimizing HIV prevention for women: A review of evidence from microbicide studies and considerations for gender-sensitive microbicide introduction. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18, 20536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA (1992). Empowering and healing the battered woman: A model for assessment and intervention. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Hatcher AM, Colvin C, & Peacock D (2013). Impact of a gender-transformative HIV and antiviolence program on gender ideologies and masculinities in two rural, South African communities. Men and Masculinities, 16, 181–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, & Abbott JT (1997). Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the Emergency Department. JAMA, 277, 1357–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PJ, Colvin C, Peacock D, & Dworkin SL (2016). What role can gender-transformative programming for men play in increasing men’s HIV testing and engagement in HIV care and treatment in South Africa? Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18, 1251–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, & Pallitto C (2017). Efficacy and feasibility of a support intervention to address intimate partner violence in antenatal care: Findings of the Safe and Sound RCT. Paper presented at Sexual Violence Research Initiative Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Palanee-Phillips T, O’Rourke S, Adewumi K, Tenza S, Mathebula F, … Montgomery ET (2019). The relationship between vaginal ring use and intimate partner violence and social harms: Formative research outcomes from the CHARISMA study in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care, 31, 660–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K, Bush R, & Sheehan M (2005). The Composite Abuse Scale: Further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence and Victims, 20, 529–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K, Sheehan M, & Schonfeld C (1999). A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the Composite Abuse Scale. Journal of Family Violence, 14, 399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4, 262–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P (1984). Psychological abuse of women by spouses and live-in lovers. Women & Therapy, 3, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Howard JA, Blumstein P, & Schwartz P (1986). Sex, power, and influence tactics in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, El-KHorazaty MN, Blake SM, & Gantz MG (2010). An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: A randomized trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 115(2 Pt 1), 273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanham M, Wilcher R, Montgomery ET, Pool R, Schuler S, Lenzi R, & Fried-land B (2014). Engaging male partners in women’s microbicide use: Evidence from clinical trials and implications for future research and microbicide introduction. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(3 Suppl 2), 19159 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman SA, Pettifor A, Rebombo D, Julien A, Wagner RG, Kang Dufour MS, … Kahn K (2017). Evaluation of the Tsima community mobilization intervention to improve engagement in HIV testing and care in South Africa: Study protocol for a cluster randomized trial. Implementation Science, 12, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, Dlamini S, Perry B, Okumu E, Sortijas S, Singh C, … Mansoor LE (2016). Social context of adherence in an open-label 1% Tenofovir Gel Trial: Gender dynamics and disclosure in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 20, 2682–2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow R, Ziskind D, & Jones D (2000). Use of female controlled microbicidal products for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Care, 12, 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, … VOICE Study Team. (2015). Tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine, 372, 509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, & Parker B (1994). Preventing abuse during pregnancy: An assessment and intervention protocol. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 19, 321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microbicide Trials Network. (2016). HOPE open-label study of vaginal ring for preventing HIV begins for former ASPIRE participants. https://mtnstopshiv.org/news/hope-open-label-study-vaginal-ring-preventing-hiv-begins-former-aspire-participants 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Minnis A, & Padian N (2005). Effectiveness of female controlled barrier methods in preventing sexually transmitted infections and HIV: Current evidence and future research directions. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81, 193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mngadi KT, Maarschalk S, Grobler AC, Mansoor LE, Frohlich JA, Madlala B, … Abdool Karim Q (2014). Disclosure of microbicide gel use to sexual partners: Influence on adherence in the CAPRISA 004 trial. AIDS and Behavior, 18, 849–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ET, Chidanyika A, Chipato T, & van der Straten A (2012). Sharing the trousers: Gender roles and relationships in an HIV-prevention trial in Zimbabwe. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14, 795–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Chitukuta M, Reddy K, Woeber K, Atujuna M, … MTN-020/ASPIRE Study Team. (2017). Acceptability and use of a dapivirine vaginal ring in a phase III trial. AIDS (London, England), 31, 1159–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Stadler J, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, … Soto-Torres L (2015). Male partner influence on women’s HIV prevention trial participation and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: The importance of “understanding”. AIDS and Behavior, 19, 784–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, Campbell JD, Donnell D, Bukusi E, … Partners PrEP Study Team. (2013). Efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high risk heterosexuals: Subgroup analyses from the Partners PrEP Study. AIDS (London, England), 27, 2155–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair G, Roberts ST, Baeten J, Palanee-Phillips T, Schwartz K, Reddy K, … Montgomery E (2016). Disclosure of vaginal ring use to male partners in an HIV prevention study: Impact on adherence. Paper presented at 2nd HIV Research for Prevention Conference, Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Nel A, van Niekirk N, Kapiga S, Bekker LG, Gama C, Gill K, … Ring Study Team. (2016). Safety and efficacy of a dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 2133–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanee-Phillips T, Roberts ST, Reddy K, Govender V, Naidoo L, Siva S, … Montgomery ET (2018). Impact of partner-related social harms on women’s adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring during a phase III trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79, 580–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto C, García-Moreno C, Stoeckel H, Hatcher A, MacPhail C, Mokoatle K, & Woollett N (2016). Testing a counselling intervention in antenatal care for women experiencing partner violence: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial in Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, Lippman SA, Gottert A, Suchindran CM, Selin A, Peacock D, … MacPhail C (2018). Community mobilization to modify harmful gender norms and reduce HIV risk: Results from a community cluster randomized trial in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21, e25134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, Lippman SA, Selin AM, Peacock D, Gottert A, Maman S, … MacPhail C (2015). A cluster randomized-controlled trial of a community mobilization intervention to change gender norms and reduce HIV risk in rural South Africa: Study design and intervention. BMC Public Health, 15, 752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipes RB, & LeBov-Keeler K (1997). Psychological abuse among college women in exclusive heterosexual dating relationships. Sex Roles, 36, 585–603. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ST, Haberer J, Celum C, Mugo N, Ware NC, Cohen CR, … Partners PrEP Study Team. (2016). Intimate partner violence and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in African women in HIV serodiscordant relationships: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 73, 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonke Gender Justice Network. (2009). One Man Can: Working with men and boys to reduce the spread of impact of HIV and AIDS. Sonke Gender Justice Network. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler J, Delany-Moretlwe S, Palanee T, & Rees H (2014). Hidden harms: Women’s narratives of intimate partner violence in a microbicide trial, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein ZA, Myer L, & Susser M (2003). The design of prophylactic trials for HIV: The case of microbicides. Epidemiology, 14, 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Bartel D, & Rubardt M (2012). Constructs of power and equity and their association with contraceptive use among men and women in rural Ethiopia and Kenya. Global Public Health, 7, 618–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RC, Umar E, Tomenson B, & Creed F (2014). Validation of the Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and the relationship between social support, intimate partner violence and antenatal depression in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry, 14, s180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2017). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales In Physical violence in American families. (pp. 29–48.) Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A, Leung WC, Leung TW, Humphreys J, Parker B, & Ho PC (2005). A randomised controlled trial of empowerment training for Chinese abused pregnant women in Hong Kong. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 112, 1249–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolley B, & Zissette S (2018). Addressing issues impacting safe and consistent use of an HIV prevention intervention: Development of a Social Benefits Harms (SBH) tool. Paper presented at 22nd International AIDS Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg W, Hendricks L, Hatcher A, Peacock D, Godana P, & Dworkin S (2013). ‘One Man Can’: shifts in father-hood beliefs and parenting practices following a gender-transformative programme in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Gender & Development, 21, 111–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Musara P, Etima J, Naidoo S, Laborde N, … Microbicide Trials Network-003D Study Team. (2015). Disclosure of pharmacokinetic drug results to understand nonadherence: Results from a qualitative study. AIDS (London, England), 29, 2161–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, … Soto-Torres L (2014). Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: The VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PloS One, 9, e89118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, & Bangsberg DR (2012). Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS, 26, F13–F19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Kintu A, Psaros C, … Bangsberg DR (2012). What’s love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV serodiscordant couples. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 59, 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodsong C, & Alleman P (2008). Sexual pleasure, gender power and microbicide acceptability in Zimbabwe and Malawi. AIDS Education & Prevention, 20, 171–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, & Farley GK (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]