Introduction

The umbrella term of “transgender” includes people who experience their gender identity as opposite to the gender assigned to them at birth and may include people who are non-binary (not exclusively masculine or feminine). For sexual transition, current standard-of-care regimens can include gender-affirming hormonal treatment (GAHT) and/or surgery. Following the pioneering work of the endocrinologist, Dr. Harry Benjamin, transgender individuals have been receiving GAHT since the early 1960s.1 Trans women are assigned to the male sex at birth, but identify with the female gender (male-to-female). To acquire and maintain feminization they undergo estrogen therapy.2

Assigned female at birth, trans men identify as male (female-to-male). They frequently pursue testosterone therapy to induce masculinization.

There are almost one million transgender adults in the United States and the proportion has increased from 0.2% in 2007 to 1.8% in 2016.3 A 2018 study by the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria in the Netherlands also reported increased referrals to their clinic since 1972. For trans women, this number increased from 14.9 per year between 1972 and 1979 to 185.2 per year between 2010 and 2014. Similarly, the annual referral rate for trans men increased from 3.8 cases (1972-1979) to 103.6 cases (2010-2014).4 As the number of transgender individuals increases, there is a growing need to understand the cancer risk in this population.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women in the United States with 126 new cases per 100,000 women each year.5 Male breast cancer only represents 1% of all breast cancer cases and less than 1% of cancers in men.6 Certain predisposing risk factors are implicated in both male and female breast carcinogenesis. Mutations in tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 are two genetic aberrations that predispose an individual to breast cancer. They account for 5-10% of female and 5-20% of male breast cancer cases.7 The frequency of breast cancer in transgender individuals, as well as the impact of GAHT on the risk of breast cancer, remains largely unexplored.

In this report, we present two cases: 1) a 32-year-old trans woman with a family history of breast cancer and a germline BRCA2 mutation; and 2) a 29-year-old trans man with a strong family history of breast cancer who was incidentally diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) upon chest reconstruction surgery. We discuss these cases from a multidisciplinary perspective thereby summarizing the current knowledge about breast cancer in transgender individuals and reviewing the inherent risk of breast cancer while undergoing GAHT.

We performed a systematic literature search in the PubMed database between 1968 and 2018 and identified two population-based observational studies which reported the incidence of breast cancer in 3102 and 5135 transgender individuals.8,9 Twenty cases of breast cancer in trans women and 16 cases in trans men have been reported (Table 1a, b).8,10–26 We also included a recent observational study on 3891 transgender individuals based on its preliminary data published in early 2018.27

Table 1a.

Synopsis of breast cancer cases in trans women (n=20)

| Reference | Age (years) | Breast Tumor Type | GAHT (years) | BRCA Mutation | Family History | Hormone Receptor Status | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmers (1968)10 | 30 | adenocarcinoma | E (−) | - | - | - | death prior to treatment |

| Symmers (l968)10 | 30 | adenocarcinoma | E (6) | - | - | - | radical mastectomy |

| Pritchard et al. (1988)11 | 35 | ductal carcinoma | E (10) | - | yes | ER−, PR+ | modified radical mastectomy, progesterone |

| Ganly and Taylor (1995)12 | 36 | ductal carcinoma | E (14) | - | - | ER− | wide local excision, continue GAHT, tamoxifen |

| Grabellus et al. (2005)13 | 46 | secretory breast carcinoma | E (−) | - | yes | ER−, PR− | - |

| Dhand and Dhaliwal (2010)14 | 58 | adenocarcinoma | E (9), break (17), E (2) | - | yes | ER+, PR+ | radiotherapy + tamoxifen + zoledronic acid |

| Pattison and McLaren (2013)15 | 43 | ductal carcinoma | E + CA (7), break (3) | - | no | ER−, PR−, HER2− | neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy |

| Gooren et al. (2013)8 | 57 | ductal carcinoma | E (36) | - | - | ER+, PR−, HER2− | - |

| Gooren et al. (2013)8 | 56 | - | E (−) | - | - | - | - |

| Maglione et al. (2014)16 | 55 | ductal carcinoma | E (30) | - | - | ER−, PR−, HER2+ | neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| Maglione et al. (2014)16 | 65 | DCIS | E (13) | no | yes | ER+ | bilateral mastectomy |

| Sattari et al. (2015)17 | 60 | ductal carcinoma | HT (7) | no | no | ER+, PR+, HER2− | radical mastectomy + reconstruction, GAHT discontinued, tamoxifen |

| Gooren et al. (2015)18 | 46 | ductal carcinoma | E (~14) | - | yes | ER+, PR+, HER+ | radical mastectomy, adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy, tamoxifen |

| Gooren et al. (2015)18 | 52 | adenocarcinoma | CA + E (30) | no | no | ER+, PR− | adjuvant chemotherapy, aromatase inhibitor, GAHT discontinued |

| Teoh et al. (2015)19 | 41 | ductal carcinoma | E + AA (14) | no | - | ER−, PR−, HER2− | wide local excision, SLNB, adjuvant chemotherapy, continues GAHT |

| Brown (2015)20 | 54 | - | - | no | - | ER−, PR− | death prior to treatment |

| Brown (2015)20 | 54 | ductal carcinoma | - | - | yes | ER+, PR−, HER2+ | - |

| Brown (2015)20 | - | - | E (7) | no | - | ER+, PR− | - |

| Gondusky (2015)21 | 51 | DCIS | E (14) | no | yes | ER−, PR−, HER2− | adjuvant chemotherapy, discontinued GAHT |

| Corman et al. (2016)22 | 46 | ductal carcinoma | CA +E (7) | BRCA2mut | yes | ER+, PR+ HER2−, AR+ | simple mastectomy + SLNB, declined tamoxifen, local relapse: radiotherapy + adjuvant chemotherapy |

AA: antiandrogen; CA: cyproterone acetate; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in-situ; E: estrogen; ER: estrogen receptor; GAHT: gender-affirming hormone therapy; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HT: hormonal treatment; PR: progesterone receptor; SLNB: sentinel lymph node biopsy; -: unknown.

Table 1b.

Synopsis of breast cancer cases in trans men (n= 16+1)

| Reference | Age (years) | Breast Tumor Type | GAHT (years) | BRCA Mutation | Family History | Hormone Receptor Status | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burcombe et al. (2003)23 | 33 | ductal carcinoma | T (13) | - | - | ER+, PR+ | mastectomy, level II axillary node clearance |

| Gooren et al. (2013)8 | 27 | adenocarcinoma | T (3) | - | - | ER+, PR+ | incidentally detected during sex reassignment surgery |

| Gooren et al. (2015)18 | 48 | ductal carcinoma | T (~9) | - | - | ER−, PR−, HER2− | adjuvant chemotherapy |

| Gooren et al. (2015)18 | 41 | ductal carcinoma | no | no | - | ER+, PR+ HER2−, AR+ | radiotherapy, chemotherapy, tamoxifen |

| Gooren et al. (2015)18 | 41 | adenocarcinoma | T (~6) | - | - | ER+, PR+, HER2− | incidentally detected during mastectomy, low dose T |

| Brown (2015)20 | 74 | ductal carcinoma | T (~3) | - | - | ER+, PR−, HER2+ | simple mastectomy, chemotherapy |

| Brown (2015)20 | 47 | - | no | - | no | ER+, PR+ | mastectomy |

| Brown (2015)20 | 64 | - | E (~2.5) | - | - | ER+, PR+ | lumpectomy + chemotherapy + tamoxifen |

| Brown (2015)20 | 42 | - | T+ E (2) | - | yes | ER+, PR+ | nipple sparing bilateral mastectomy |

| Brown (2015)20 | 57 | - | E + MP (~2) | - | no | - | lumpectomy + radiotherapy |

| Brown (2015)20 | 42 | - | T (3) | - | no | - | bilateral total mastectomy + subsequent reconstruction |

| Brown (2015)20 | 48 | - | no | - | - | ER+, PR+ | mastectomy |

| Shao et al. (2011)24 | 53 | ductal carcinoma | T (5) | no | yes | ER+, PR−, HER2+++ | bilateral mastectomy + adjuvant chemotherapy + trastuzumab, aromatase inhibitor, T (topical) |

| Shao et al. (2011)24 | 27 | ductal carcinoma | T (6) | no | yes | ER+, PR+, HER2+++ | bilateral mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy, trastuzumab (recommendation: bilateral salpingectomy , tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitor) resumed T |

| Nikolic et al. (2012)25 | 42 | ductal carcinoma | T (1.5) | - | no | ER−, PR−, HER2+++, AR+ | neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radical mastectomy + axillary dissection, adjuvant chemotherapy + trastuzumab |

| Katayama et al. (2016)26 | 41 | neuroendocrine carcinoma | T (15) | - | no | ER+, PR+, HER2− | residual mammary gland was removed, SNLB, aromatase inhibitor, adjuvant radiotherapy |

| Eismann et al. (2018) | 29 | DCIS | T (4) | no | yes | ER+ | intensive screening |

DCIS: ductal carcinoma in-situ; E: estrogen; ER: estrogen receptor; GAHT: gender-affirming hormone therapy; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; MP: medroxyprogesterone; PR: progesterone receptor; SNLB: sentinel lymph node biopsy; T: testosterone, -: unknown.

Case Reports

Trans woman

A 32-year-old trans woman initiated estrogen therapy (6mg estrogen daily) at the age of 26. She underwent genetic mutation screening because her 29-year-old sister was diagnosed with BRCA2-mutation-related breast cancer. The individual was determined to carry the same deleterious BRCA2 mutation. She underwent bilateral orchiectomy and continued estrogen treatment. The family history revealed that her mother, mother’s twin and paternal aunt had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Her mother and mother’s twin were premenopausal at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. Her father was also diagnosed with prostate cancer. The family history was negative for ovarian and pancreatic cancer. Given the positive genetic screening result, she underwent high-risk screening mammography for hormone-mediated breast development. The exam was interpreted as BI-RADS 1 (i.e., negative). A preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was unremarkable. Given her family history and BRCA2 positivity, the individual opted for primary breast cancer risk reduction with bilateral skin sparing mastectomies. Tissue expanders were placed at the time of surgery for implant-based breast reconstruction. The mastectomy specimen showed no evidence of malignancy in either breast.

Trans man

A 29-year old trans man has been receiving testosterone (testosterone cypionate 80mg/week IM) for four years and achieved a hormone profile consistent with menopause (FSHhigh, LHhigh, estradiollow). He proceeded to chest reconstruction surgery and pathological assessment revealed estrogen receptor (ER) positive (>90%), high-grade DCIS in the left breast. The right breast showed no evidence of malignancy. The individual had a strong family history of male breast cancer, which occurred in two paternal great uncles. He underwent genetic testing using a breast cancer screening panel consisting of 23 genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, DICER1, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PALB2, PMS2, PTEN, RAD50, RAD51C, RAD51D, SMARCA4 STK11 and TP53). No mutations or variants were detected. Following chest reconstruction surgery, he underwent MRI to assess the presence of any residual breast tissue. Residual tissue was detected on both sides along with an enlarged lymph node in the left axilla. As a result, he underwent ultrasound which showed a mildly abnormal node with the cortex measuring up to 5-6 mm. The node was assessed by fine-needle aspiration, which was negative for malignant cells. He was offered adjuvant radiation therapy, which he declined.

Discussion

Trans women

Standard of care.

Male-to-female transition is typically initiated during adulthood or late adolescence where the median age to start hormonal treatment is 30 years.27 However, transgender adolescents (Tanner stage 2) may decide to suppress puberty with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues until age 16, after which they may be given GAHT.28 GAHT regimens for trans women differ from hormone supplementation regimens for postmenopausal women. Aiming at achieving premenopausal serum levels (100-200 pg/ml), current protocols administer estrogen at substantially higher and fixed doses along with antiandrogens to suppress serum testosterone levels to the normal range of premenopausal females (<50 ng/dl).2 Despite a potentially higher risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular events, additional progestin may be included in GAHT to aid in full breast development.29 Table 2a provides a synopsis of clinical regimens and compares the current GAHT dosing recommendations to postmenopausal hormone therapy.

Table 2a.

Hormone regimens in trans women (versus postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT))

| Class | Drug | Formulation | Dose recommendation in male-to-female transition | Dose recommendation in postmenopausal HT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | Estrogen | Oral | 2.0-6.0 mg/d | 0.5-2.0 mg/d |

| Estradiol patch | Transdermal | 0.025-0.2 mg/d | 0.0025-0.1 mg/d | |

| Estradiol valerate | Intramuscular | 5-30 mg biweekly or 2-10 mg weekly | Not recommended | |

| Antiandrogen | Spironolactone | Oral | 100-300 mg/d | Not recommended |

| Cyproterone acetate | Oral | 25-50 mg/d | Not recommended | |

| GnRH-agonist | Goserelin | Intramuscular | 3.75 mg monthly or 11.25 mg every three months | Not recommended |

Twelve months of hormonal therapy are recommended prior to breast augmentation and are imperative for genital surgery (orchiectomy, penectomy, vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty, labiaplasty).30 At the same time, all further aesthetic interventions (e.g. facial feminization, thyroid cartilage reduction) do not require a defined period of prior GAHT according to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines published in 2011.30

In principle, GAHT is a lifelong procedure. However, it still remains unclear whether or not to induce menopause in trans women as they age to avoid the long-term side effects of high-dose estrogens. Many transgender individuals prefer to continue high-dose GAHT and dose adjustments remain at the discretion of caregivers who should discuss the benefits and the respective risks with the individual.31

Breast cancer incidence.

Numbers on the incidence of breast cancer in trans women receiving GAHT remain vague. As of 2018, two population-based studies assessed the breast cancer risk attributable to GAHT. Both studies were limited by small numbers of breast cancer cases and a lack of genetic risk stratification.8,9 Thus, their data must be interpreted with caution. The first study by Gooren and colleagues consisted of two breast cancer cases among 2307 Dutch trans women undergoing androgen deprivation and estrogen administration.8 They reported an estimated rate of breast cancer of 4.1 per 100 000 person-years. This was lower than expected for women (170 per 100 000) but above the expected frequency of male breast cancer (1.2 per 100 000). Table 3 provides a synopsis of the calculated breast cancer risk, noting that numbers vary as incidence per 100 000 patient years in this study had been normalized to trans women and trans men specimen, respectively.8 The second study by Brown and Jones was conducted using the United States Veterans Health Administration database of 3556 trans women with three breast cancer cases. There were 22.1 breast cancer cases per 100 000 patient-years of estrogen therapy between 1996 and 2013.9 It must be noted that only 52% of all patients in this cohort received prior GAHT and that all three cases of breast cancer detected did not receive any hormonal treatment before diagnosis. Both studies concluded that there is no increased incidence in breast cancer in trans women.

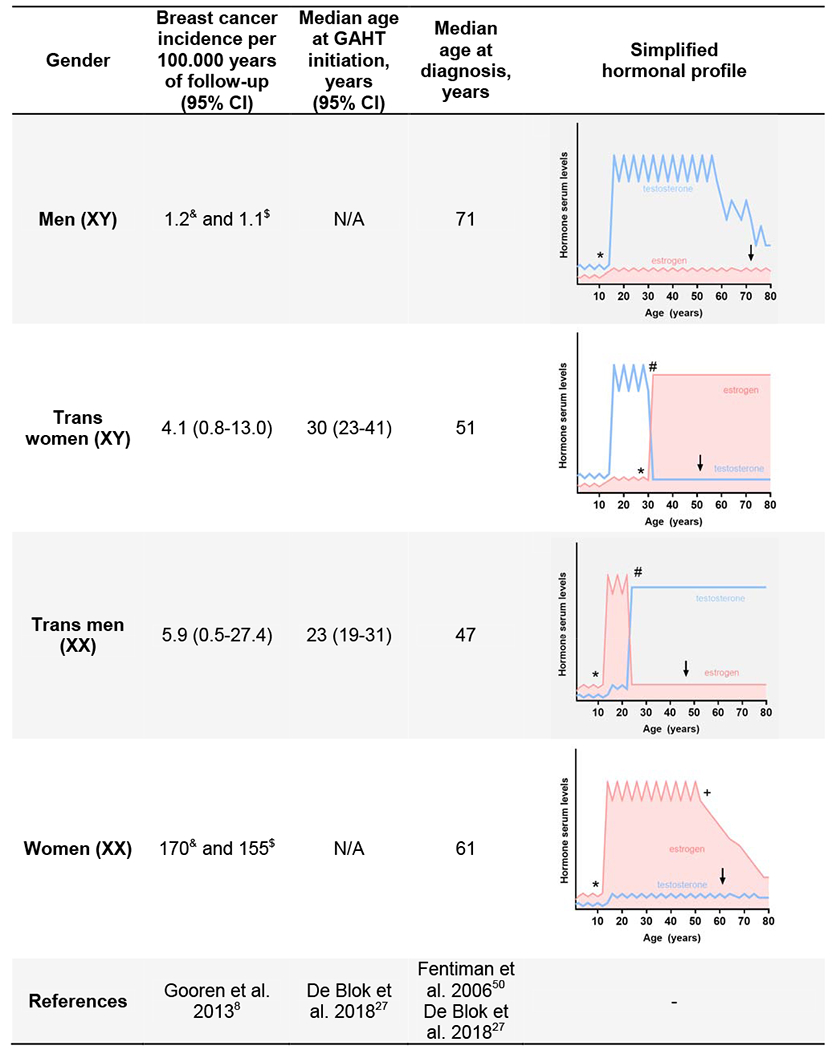

Table 3.

Synopsis of breast cancer risk and median age of diagnosis

|

GAHT: gender-affirming hormone treatment; calculated expected incidence compared to trans women (&); calculated expected incidence compared to trans men ($); puberty (*); initiation of GAHT (#); menopause (+); breast cancer diagnosis (↓)

A preliminary 2018 investigation by de Blok and colleagues identified 18 cases of breast cancer (80% were ER positive) in a cohort of 2567 trans women receiving GAHT for a median duration of 222 months.27 In this cohort, the median age of trans women diagnosed with breast cancer was 51 years compared to a median of 61 years among the general female Dutch population (Table 3). The incidence of breast cancer in trans women was considered higher than the risk in Dutch men (0.4 cases expected) but below the expected reference for Dutch women (72 cases expected). The authors concluded that trans women taking GAHT are at an increased risk of breast cancer compared to the male Dutch population.

Impact of GAHT and genetics on breast cancer risk.

Given the limited clinical experience in transgender medicine, hormonal treatment in postmenopausal women may provide an approximation to estimate the risk of breast cancer in trans women. In the Million Women Study on 1,084,110 British postmenopausal women receiving hormonal treatment, 66% showed an increased risk of breast cancer, noting the highest risk was in women taking estrogen-progestogen combinations (100% increased risk).32 Another study of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 matched controls reported that for each year beyond five years of hormonal treatment, the risk of breast cancer increases by 35%.33 It is important to note that GAHT in trans women is given at significantly higher doses and for longer periods as compared to postmenopausal hormonal treatment (Table 3). Since GAHT is nowadays initiated at increasingly younger age and continues into senescence, individuals are subjected to far longer exposure periods than previously reported.4 Therefore, it is important to follow and document the impact of long-term estrogen exposure on the mammary epithelium in trans women and to determine the risk of breast cancer. In this context, breast tissues from trans women (retrieved during breast augmentation) and trans men (retrieved during chest reconstruction surgery) may provide a valuable proxy to study how exogenous hormones influence breast carcinogenesis.

Genetic predisposition has to be taken into account when initiating feminization in trans women. The lifetime breast cancer risk for women is 12%, whereas 72% of women with a BRCA1 mutation and 69% of women with a BRCA2 mutation will develop breast cancer by the age of 80.5,34 Male breast cancer cases are more often associated with BRCA2 than BRCA1 mutations.35 Male BRCA2 carriers have a 6.8% lifetime risk compared to 0.1% in the normal male population.36 Ninety percent of male breast cancer cases are ER positive and progesterone receptor positive.37

General screening recommendations.

Phillips et al. recently proposed guidelines to screen for breast cancer in trans women on GAHT. Annual mammography screening is recommended in trans women that are 1) older than 50 years of age, 2) continuously undergoing GAHT, and 3) have additional risk factors such as estrogen and progestin use for more than five years, a body mass index >35 kg/m2 or a positive family history.38 The age cut-off of 50 years is based on the diagnostic limitations of mammography, as both mammography sensitivity and specificity increase with age.39 Consequently, in younger trans women, the predictive value and benefits of mammography may not outweigh the costs, inconvenience and emotional distress associated with the procedure. As of yet, these guidelines are not based on comprehensive long-term data but may be used to direct clinical care.

Trans woman case discussion summary.

In the trans woman described here, it is reasonable to assume that the germline BRCA2 mutation puts her at a 6.8% risk for developing breast cancer, and her risk is possibly further increased by GAHT. She continues on estradiol therapy 2 mg three times a day. Given the increased odds and her sister diagnosed with breast cancer, the individual opted for prophylactic bilateral mastectomies. She is being followed with self- and clinical breast exams. BRCA2 mutation carriers are also at risk of developing pancreatic and prostate cancer.40 As the prostate is usually not removed with sex reassignment surgery, recommendations for prostate cancer screening remain valid for trans women. Prostate-specific antigen testing should be performed at the age of 40 and repeated every one to four years in these at-risk individuals.41 With regard to her ongoing estrogen therapy, her hormone profile is being monitored according to current guidelines in order to minimize the risk for thromboembolic events, hypertension and cholestasis.28,30

Trans men

Standard of care.

The median age to initiate GAHT in female-to-male transition is 23 years.27 Hormone regimens for trans men follow the general principle of hormone supplementation in male hypogonadism. Testosterone is administered aiming at levels within the normal reference range for men (320-1000 ng/dl, Table 2b).2 After twelve continuous months of hormone therapy genital surgery (e.g. hysterectomy, ovarectomy, vaginectomy, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty, scotoplasty) may be performed. No prior testosterone therapy is mandatory for chest-contouring surgery or aesthetic interventions.30

Table 2b.

Hormone regimens in trans men

| Class | Drug | Formulation | Dose recommendation in female-to-male transition | Dose recommendation in breast cancer patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | Testosterone enanthate/cy-pionate | Intramuscular Subcutaneous | 100-200mg biweekly 50-100mg weekly | Not recommended |

| Testosterone undecanoate | Intramuscular | 1000mg every 12 weeks | Not recommended | |

| Testosterone gel 1.6% | Transdermal | 50-100 mg/d | Not recommended, but a single case observation suggests feasibility23 | |

| Testosterone patch | Transdermal | 2.5-7.5 mg/d | Not recommended | |

| GnRH analogs | Intramuscular | NA | Not recommended | |

| Progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone | Intramuscular | NA | Not recommended |

Chest-contouring surgery, unlike mastectomy for oncological or risk-reducing purposes, does not remove the entire mammary tissue as it remains a surgical procedure that is not defined by anatomic boundaries. This strategy entails the removal of the majority of breast tissue accompanied by repositioning of the nipple-areolar complex and obliteration of the inframammary fold including radial scoring if needed. When a mastectomy is performed, the breast tissue is removed according to anatomical borders in a sub-dermal plane to ensure the majority of the breast tissue has been removed. This may lead to a sub-optimal aesthetic outcome as compared to chest-contouring surgery.

Breast cancer incidence.

Current knowledge on the incidence of breast cancer in trans men undergoing GAHT is limited to the two aforementioned population-based studies. Gooren and colleagues monitored a cohort of 795 trans men receiving GAHT over a course of 36 years (1975-2011). In this period, the authors detected one case of breast cancer, leading to a calculated incidence of 5.9 cases per 100 000 person-years.8 Brown and Jones examined 1579 trans men over a course of 17 years and detected seven cases of breast cancer. This led to a calculated incidence of 105.2 cases per 100.000 patient-years. However, only three out of seven individuals received GAHT prior to breast cancer diagnosis. It must be noted that in the study by Gooren and colleagues, trans men over 65 years were critically under-represented (13/795 [0.2%]) as compared to the cohort investigated by Brown and Jones (396/1579 [25.1%]).9 Likewise, both studies concluded that there is no increased breast cancer incidence in trans men.

De Blok and colleagues identified four breast cancer cases in 1324 trans men (50% cases were ER-positive).27 Three of the four cases were diagnosed several years after mastectomy. The median duration of GAHT at the time of breast cancer diagnosis was 176 months. This frequency appears to be lower than that in women (21 cases expected in the same time period) but higher than in men (0.1 cases expected in the same time period). The low number of breast cancer cases in trans men in this study could be the result of the estradiol-low state of trans men, but could also be explained by the younger median age at diagnosis of 47 years old (range: 35 to 59 years) which was similar to that of trans women (median age of diagnosis: 51 years; range: 30 to 73 years) but considerably lower than the female reference population (median age of diagnosis: 61 years; Table 3).

Impact of GAHT and genetics on breast cancer risk.

Based on prior preclinical and clinical studies, it may be hypothesized that testosterone is protective with regard to breast cancer risk.42–44 At the same time, breast tissue removal as part of the routine gender reassignment in trans men may be the central driver for breast cancer risk reduction. Whether there is a risk-reducing effect of testosterone supplementation in the absence of surgery is not yet clear.

It has been discussed that at high levels, testosterone can be partially aromatized to estradiol and could conceivably drive endometrial or breast cancer development.24 If this was the case, aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole) might be useful to prevent breast cancer.45 However, Chan et al observed that when exogenous testosterone is used to achieve testosterone levels that fall within the normal range for men, serum estradiol levels in transgender men do not increase and actually fall, possibly due to a decrease in body fat and/or suppression of the hypothalamic pituitary axis.46

In the trans man case presented here, low endogenous estradiol levels support these observations and suggest that exogenously administered testosterone did not reach a critically high level to be aromatized to estradiol.

Testosterone acts via the androgen receptor (AR) which is widely expressed in all molecular subtypes of breast cancer and has been reported in 86% of DCIS.47 AR signaling has been described as anti-estrogenic in ER-positive breast cancer. In the absence of ER signaling, however, it may become a pro-proliferative stimulus.48 No clinical study has yet systematically compared the benefit and risks of androgen supplementation once a transgender patient is being treated for ER-negative or ER-positive breast cancer. The trans man described here had ER-positive DCIS and the tissue was not tested for AR expression. In this case estradiol and dihydrotestosterone levels are closely monitored to enable adjustment of testosterone dosing and to minimize the potential risk attributable to exogenous GAHT.

Given this individual’s strong family background for male breast cancer and despite him testing negative for 23 breast cancer related genes, he may still harbor an undetected genetic alteration. Thus, a hereditary component, which increases his risk of breast cancer is likely present but yet remains to be accurately diagnosed.

General screening recommendations.

Screening recommendations in trans men are dependent on the surgical intervention performed. For genetically predisposed trans men, bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy can be recommended; if a mastectomy is performed, there would be no need for further imaging for screening purposes. Since the majority of trans men undergo chest reconstruction for their gender confirmation surgery, annual examinations of the sub- and periareolar breast, along with chest wall and axillary examinations remain the main screening tool.38 For trans men who undergo breast reduction or retain their prior anatomy, routine annual screening should be performed by mammography starting at the age of 40 years.38,49 If there is minimal residual breast tissue and mammography is not feasible, ultrasound and MRI can be performed. This is because breast cancer may occur in residual breast tissue after chest-contouring surgery and testosterone supplementation.23,25,27

Trans man case discussion summary.

In the trans man case, DCIS was diagnosed in the course of chest reconstruction surgery. No additional surgical excision of the residual breast tissue was performed. He currently receives intensive screening including biannual alternating imaging of the residual breast tissue by MRI and ultrasound as mammogram is not feasible. Clinical experience on the use of testosterone supplementation once an early stage of ER positive breast cancer has been diagnosed remains limited. To maintain masculinization, low dose transdermal application of testosterone may be applied as these doses may minimize the amount of circulating testosterone and thus avoid unnecessary aromatization to estradiol.23

Trans women and Trans men

Psychosocial implications.

The physical changes induced by sexual transition are usually accompanied by great psychosocial relief of the respective individual.2 Recommendations that may terminate the pursuit of further feminization in trans women and masculinization in trans men are usually unacceptable. Consequently, future research into the therapeutic strategies for breast cancer in transgender people will have to be done with the goal to harmonize the intended and hazardous effects of hormonal treatment.

Conclusion

The risk of breast cancer in transgender individuals receiving GAHT remains largely unexplored. Screening for genetic risk and early diagnosis are crucial as pausing GAHT upon breast cancer diagnosis is often not desired by the transgender individual. Dedicated long-term studies in transgender populations with comprehensive data on the impact of GAHT are urgently needed to better estimate breast cancer risk and to tailor clinical guidelines particularly for those individuals at genetic risk. Further, systematic observational studies of transgender individuals may allow us to better understand the differential contributions of exogenous hormones, genetics and their interaction to breast cancer risk. Prospective planning of these studies is urgently needed to gather data that can guide the care for transgender individuals as they age.

Clinical Practice Points.

The estimated proportion of transgender adults in the United States has increased from 0.2% in 2007 to 1.8% in 2016.

With increasing cultural and social acceptance, more transgender individuals are undergoing gender-affirming treatment.

The impact of gender-affirming hormonal treatment (GAHT) on the risk of hormone-dependent malignancies in transgender individuals, including breast cancer, remains largely unexplored.

In this report we present two cases: a 32-year old trans woman with a family history of breast cancer and a germline BRCA2 mutation and a 29-year old trans man with a family history of male breast cancer who was incidentally diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) upon chest reconstruction surgery.

GAHT is a lifelong therapeutic regimen. As a result, long-term observational studies are critically needed to assess the lifetime breast cancer risk in transgender individuals.

Comprehensive and individually tailored screening programs for transgender individuals are crucial for determining the genetic risk, especially if family history points towards a hereditary predisposition.

Future strategies to manage trans women may include gradual reduction of exogenous estrogen doses with age, thereby simulating natural menopause.

In trans men, further studies are needed to assess the potential risks of constant testosterone exposure. Aromatase inhibitors could potentially prevent testosterone aromatization to estradiol, but have not yet been systematically studied in this context.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank both individuals who were outlined in the given case report, including their friends and families.

Funding

JE is supported by a Deutsche Krebshilfe Postdoctoral Fellowship. YJH is supported by the Klarman Family Foundation. GMW is supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF 17-174), the Ludwig Center at Harvard Medical School and NIH R01 CA226776-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

All authors declare no conflicts to disclose in respect to the given publication.

References

- 1.Benjamin H Clinical Aspects of Transsexualism in the Male and Female. Am J Psychother. 1964;18:458–469. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1964.18.3.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Endocr Pract Off J Am Coll Endocrinol Am Assoc Clin Endocrinol. 2017;23(12):1437. doi: 10.4158/1934-2403-23.12.1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender Population Size in the United States: a Meta-Regression of Population-Based Probability Samples. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, de Blok CJM, et al. The Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria Study (1972-2015): Trends in Prevalence, Treatment, and Regrets. J Sex Med. 2018;15(4):582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018;124(13):2785–2800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet Lond Engl. 2006;367(9510):595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68226-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MAA, Giltay EJ, van Diest PJ. Breast cancer development in transsexual subjects receiving cross-sex hormone treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3129–3134. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191–198. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3213-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Symmers WS. Carcinoma of breast in trans-sexual individuals after surgical and hormonal interference with the primary and secondary sex characteristics. Br Med J. 1968;2(5597):83–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pritchard TJ, Pankowsky DA, Crowe JP, Abdul-Karim FW. Breast cancer in a male-to-female transsexual. A case report. JAMA. 1988;259(15):2278–2280. doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03720150054036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganly I, Taylor EW. Breast cancer in a trans-sexual man receiving hormone replacement therapy. Br J Surg. 1995;82(3):341. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabellus F, Worm K, Willruth A, et al. ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in a secretory carcinoma of the breast of a male-to-female transsexual. Breast Edinb Scotl. 2005;14(1):71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhand A, Dhaliwal G. Examining patient conceptions: a case of metastatic breast cancer in an African American male to female transgender patient. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):158–161. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1159-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pattison ST, McLaren BR. Triple negative breast cancer in a male-to-female transsexual. Intern Med J. 2013;43(2):203–205. doi: 10.1111/imj.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maglione KD, Margolies L, Jaffer S, et al. Breast cancer in male-to-female transsexuals: use of breast imaging for detection. AJR Am J Roentgenol.2014;203(6):W735–740. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattari M Breast cancer in male-to-female transgender patients: a case for caution. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15(1):e67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gooren L, Bowers M, Lips P, Konings IR. Five new cases of breast cancer in transsexual persons. Andrologia. 2015;47(10):1202–1205. doi: 10.1111/and.12399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teoh ZH, Archampong D, Gate T. Breast cancer in male-to-female (MtF) transgender patients: is hormone receptor negativity a feature? BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-209396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown GR. Breast Cancer in Transgender Veterans: A Ten-Case Series. LGBT Health. 2015;2(1):77–80. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gondusky CJ, Kim MJ, Kalantari BN, Khalkhali I, Dauphine CE. Examining the role of screening mammography in men at moderate risk for breast cancer: two illustrative cases. Breast J. 2015;21(3):316–317. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corman V, Potorac I, Manto F, et al. Breast cancer in a male-to-female transsexual patient with a BRCA2 mutation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(5):391–397. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burcombe RJ, Makris A, Pittam M, Finer N. Breast cancer after bilateral subcutaneous mastectomy in a female-to-male trans-sexual. Breast Edinb Scotl. 2003;12(4):290–293. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(03)00033-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao T, Grossbard ML, Klein P. Breast cancer in female-to-male transsexuals: two cases with a review of physiology and management. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011;11 (6):417–419. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolic DV, Djordjevic ML, Granic M, et al. Importance of revealing a rare case of breast cancer in a female to male transsexual after bilateral mastectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:280. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katayama Y, Motoki T, Watanabe S, et al. A very rare case of breast cancer in a female-to-male transsexual. Breast Cancer Tokyo Jpn. 2016;23(6):939–944. doi: 10.1007/s12282-015-0661-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Blok CJM, Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, et al. Breast cancer in transgender persons receiving gender affirming hormone treatment: results of a nationwide cohort study. Endocr Abstr. 2018;56:P955. doi: 10.1530/endoabs.56.P955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-Van De Waal HA, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH). Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming Peope. September 2011. https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/SOC%20v7/SOC%20V7_English.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2018.

- 31.den Heijer M, Bakker A, Gooren L. Long term hormonal treatment for transgender people. BMJ. 2017;359:j5027. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beral V, Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2003;362(9382):419–427. doi: 10.106/S0140-6736(03)14065-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calle EE, Heath CW, Coates RJ, et al. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: Collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Lancet. 1997;350(9084):1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08233-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2402–2416. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4282–4288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, Chen S. Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(23):1811–1814. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansen Taber KA, Morisy LR, Osbahr AJ, Dickinson BD. Male breast cancer: risk factors, diagnosis, and management (Review). Oncol Rep. 2010;24(5):1115–1120. doi: 10.3892/or_00000962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips J, Fein-Zachary VJ, Mehta TS, Littlehale N, Venkataraman S, Slanetz PJ. Breast imaging in the transgender patient. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(5):1149–1156. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong K, Moye E, Williams S, Berlin JA, Reynolds EE. Screening mammography in women 40 to 49 years of age: a systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):516–526. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, et al. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(8):1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carroll PR, Parsons JK, Andriole G, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Version 2.2016. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw JNCCN. 2016;14(5):509–519. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glaser RL, Dimitrakakis C. Reduced breast cancer incidence in women treated with subcutaneous testosterone, or testosterone with anastrozole: a prospective, observational study. Maturitas. 2013;76(4):342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimitrakakis C, Zhou J, Wang J, et al. A physiologic role for testosterone in limiting estrogenic stimulation of the breast. Menopause N Y N. 2003;10(4):292–298. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000055522.67459.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eigeliene N, Elo T, Linhala M, Hurme S, Erkkola R, Härkönen P. Androgens inhibit the stimulatory action of 17β-estradiol on normal human breast tissue in explant cultures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(7):E1116–1127. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2014;383(9922):1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan KJ, Jolly D, Liang JJ, Weinand JD, Safer JD. Estrogen levels do not rise with testosterone treatment for transgender men. Endocr Pract Off J Am Coll Endocrinol Am Assoc Clin Endocrinol. 2018;24(4):329–333. doi: 10.4158/EP-2017-0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moinfar F, Okcu M, Tsybrovskyy O, et al. Androgen receptors frequently are expressed in breast carcinomas: potential relevance to new therapeutic strategies. Cancer. 2003;98(4):703–711. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hickey TE, Robinson JLL, Carroll JS, Tilley WD. Minireview: The androgen receptor in breast tissues: growth inhibitor, tumor suppressor, oncogene? Mol Endocrinol Baltim Md. 2012;26(8):1252–1267. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):297–316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet Lond Engl. 2006;367(9510):595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68226-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]