Abstract

Background

Foot ulcers in people with diabetes mellitus are a common and serious global health issue. Dressings form a key part of ulcer treatment, with clinicians and patients having many different types to choose from. A clear and current overview of current evidence is required to facilitate decision‐making regarding dressing use.

Objectives

To summarize data from systematic reviews of randomised controlled trial evidence on the effectiveness of dressings for healing foot ulcers in people with diabetes mellitus (DM).

Methods

We searched the following databases for relevant systematic reviews and associated analyses: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 2); Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 1); Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, 14 April 2015); Ovid EMBASE (1980 to 14 April 2015). We also handsearched the Cochrane Wounds Group list of reviews. Two review authors independently performed study selection, risk of bias assessment and data extraction. Complete wound healing was the primary outcome assessed; secondary outcomes included health‐related quality of life, adverse events, resource use and dressing performance.

Main results

We found 13 eligible systematic reviews relevant to this overview that contained a total of 17 relevant RCTs. One review reported the results of a network meta‐analysis and so presented information on indirect, as well as direct, treatment effects. Collectively the reviews reported findings for 11 different comparisons supported by direct data and 26 comparisons supported by indirect data only. Only four comparisons informed by direct data found evidence of a difference in wound healing between dressing types, but the evidence was assessed as being of low or very low quality (in one case data could not be located and checked). There was also no robust evidence of a difference between dressing types for any secondary outcomes assessed.

Authors' conclusions

There is currently no robust evidence for differences between wound dressings for any outcome in foot ulcers in people with diabetes (treated in any setting). Practitioners may want to consider the unit cost of dressings, their management properties and patient preference when choosing dressings.

Plain language summary

Dressings to treat foot ulcers in people with diabetes

Background

Diabetes mellitus (generally known as 'diabetes'), when untreated, causes a rise in the sugar (glucose) levels in the blood. It is a serious health issue that affects millions of people around the world (e.g., almost two million people in the UK and 24 million people in the USA). Foot ulcers are a common problem for people with diabetes; at least 15% of people with diabetes have foot ulcers at some time during their lives. Wound dressings are used extensively in the care of these ulcers. There are many different types of dressings available, from basic wound contact dressings to more advanced gels, films, and specialist dressings that may be saturated with ingredients that exhibit particular properties (e.g. antimicrobial activity). Given this wide choice, a clear and up‐to‐date overview of the available research evidence is needed to help clinicians/practitioners to decide which type of dressing to use.

Review question

What is the evidence that the type of wound dressing used for foot ulcers in people with diabetes affects healing?

What we found

This overview drew together and summarised evidence from 13 systematic reviews that contained 17 relevant randomised controlled trials (the best type of study for this type of question) published up to 2013. Collectively, these trials compared 10 different types of wound dressings against each other, making a total of 37 separate comparisons. The different ways in which dressing types were compared made it difficult to combine and analyse the results. Only four of the comparisons informed by direct data found evidence of a difference in ulcer healing between dressings, but these results were classed as low quality evidence.

There was no clear evidence that any of the 'advanced' wound dressings types were any better than basic wound contact dressings for healing foot ulcers. The overview findings were restricted by the small amount of information available (a limited number of trials involving small numbers of participants).

Until there is a clear answer about which type of dressing performs best for healing foot ulcers in people with diabetes, other factors, such as clinical management of the wound, cost, and patient preference and comfort, should influence the choice of dressing.

This plain language summary is up‐to‐date as of April 2015.

Background

Also see Glossary (Appendix 1).

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus (DM; high glucose levels in the blood) is a common condition that affects 1.8 million people in the UK (approximately 3% of the population) and 24 million in the USA. Incidence of DM is projected to increase rapidly over the next 25 years (WHO 2005). Global projections suggest that the worldwide prevalence of DM could rise to 4.4% by 2030, which would mean that approximately 366 million people would be affected (Wild 2004).

Success in treating DM has improved the life expectancy of patients. However, the increased prevalence of DM, coupled with the extended time people now live with the disease, has led to increased numbers of DM‐related complications, such as neuropathy (nerve damage) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Both PAD and neuropathy are risk factors for the development of chronic foot ulceration in people with DM (Pecoraro 1990; Reiber 1999), as are other physical issues such as joint deformity (Abbott 2002). PAD and neuropathy can occur separately (ischaemic foot and neuropathic foot, respectively), or in combination (in the neuroischaemic foot). Foot ulceration is reported to affect 15% or more of the diabetic population at some time in their lives (Reiber 1996; Singh 2005). Estimates from UK surveys indicate that around 1% to 4% of people with DM have foot ulcers at any given time (Abbott 2002; Kumar 1994). In 2008, the prevalence of having at least one foot ulcer was 8% amongst people with DM receiving Medicare in the USA (Margolis 2011).

An ulcer forms as a result of damage to the epidermis (skin) and subsequent loss of underlying tissue. Specifically, the International Consensus on the Diabetic Foot defines a foot ulcer as a wound that extends through the full thickness of the skin below the level of the ankle (Apelqvist 2000a). This is irrespective of duration (although some definitions of chronic ulceration require a duration of six weeks or more), and the ulcer can extend to muscle, tendon and bone. Foot ulcers in people with DM can be graded for severity using a number of systems. The Wagner wound classification system was one of the first described, and has, historically, been widely used, although it is now rarely used in clinical practice (Wagner 1981). The system assesses ulcer depth and the presence of osteomyelitis (bone infection) or ischemia and infection and grades them as: grade 0 (pre‐ or post‐ulcerative lesion); grade 1 (partial/full‐thickness ulcer); grade 2 (probing to tendon or capsule); grade 3 (deep with osteitis (bone inflammation)); grade 4 (partial foot gangrene); and grade 5 (whole foot gangrene). Newer grading systems, such as the PEDIS system (Schaper 2004), the University of Texas Wound Classification System and SINBAD (Ince 2008; Oyibo 2001), have been developed, with variable validation (Karthikesalingam 2010).

Foot ulcers in people with DM have a serious impact on their health‐related quality of life (Nabuurs‐Franssen 2005; Ribu 2006), and treating people with DM and foot ulcers incurs costs to the health system ‐ not only for dressings applied, but also for staff (for podiatry, nurses, doctors), tests and investigations, antibiotics and specialist footwear. Twelve years ago the cost of diabetic foot ulceration to the UK National Health Service was believed to be about GBP 12.9 million annually (Lewis 2013); this figure will have increased significantly since. The economic impact is also high in terms of the personal costs to patients and carers, and includes costs associated with lost work time and productivity while the patient is non‐weight bearing (taking weight off the affected foot), or hospitalised. As many as 85% of foot‐related amputations are preceded by ulceration (Apelqvist 2000b; Pecoraro 1990).

In terms of ulcer healing, a meta‐analysis of trials in which people with neuropathic foot ulcers received good wound care reported that 24% of ulcers attained complete healing by 12 weeks and 31% by 20 weeks (Margolis 1999). Reasons for delayed healing might include: infection (especially osteomyelitis), co‐morbidities and the size and depth of ulcer at presentation. Even when ulcers do heal, the risk of ulcer recurrence is high. Pound 2005 reported that 62% of ulcer patients (n = 231) became ulcer‐free at some stage over a 31‐month observation period. However, 40% of the ulcer‐free group went on to develop a new or recurrent ulcer after a median period of 126 days. The ulcer recurrence rate over five years can be as high as 70% (Dorresteijn 2010; Van Gils 1999). Failure of ulcers to heal may result in amputation, and people with DM have a 10‐ to 20‐fold higher risk of losing a lower limb, or part of a lower limb, due to non‐traumatic amputation than those without DM (Morris 1998; Wrobel 2001).

Description of the interventions

The treatment of foot ulcers in people with DM comprises several strategies, some of which may be used concurrently. These include: pressure relief (i.e. off‐loading ‐ taking weight off the affected foot); wearing special footwear, or shoe inserts, that are designed to redistribute load on the surface of the foot; removal of dead cellular material from the surface of the wound (debridement or desloughing); infection control; and the use of wound dressings. Other general treatment strategies include: patient education (e.g. in relation to foot care, or other aspects of self‐management); optimisation of blood glucose control; correction (where possible) of arterial insufficiency, for example with arterial reconstruction surgery; and other surgical interventions such as debridement, drainage of pus and amputation.

Dressings are widely used in wound care, both to protect the wound and to promote healing. Classification of a dressing normally depends on the key material used. Several attributes of an ideal wound dressing have been described (BNF 2014), including:

the ability of the dressing to absorb and contain exudate without leakage or strike‐through;

lack of particulate contaminants left in the wound by the dressing;

thermal insulation;

impermeability to water and bacteria;

avoidance of wound trauma on dressing removal;

frequency with which the dressing needs to be changed (less frequent dressing changes seen as positive);

provision of pain relief; and

comfort.

There is a vast choice of dressings available to treat chronic wounds like foot ulcers in people with DM. For ease of comparison this review has categorised dressings according to the British National Formulary 2010 (BNF 2014), which is freely available via the Internet. We will use 'generic' names where possible, also providing UK trade names and manufacturers, where these are available, to allow cross‐reference with the BNF. However, it is important to note that the way dressings are categorised, as well as dressing names, manufacturers and distributors of dressings may vary from country to country, so these are provided as a guide only. A description of all categories of dressings is given below and brief summaries of key terms, including dressing types can be found in the glossary (Appendix 1).

1. Basic wound contact dressings

Low‐adherence dressings and wound contact materials

Low‐adherence dressings and wound contact materials usually consist of cotton pads that are placed directly in contact with the wound. These can be non‐medicated (e.g. paraffin gauze dressing), or medicated (e.g. containing povidone iodine or chlorhexidine). Examples include paraffin gauze dressing, BP 1993 and Xeroform® (Covidien) dressing (a non‐adherent petrolatum blend with 3% bismuth tribromophenate on fine mesh gauze).

Absorbent dressings

Absorbent dressings are applied directly to the wound, and may be used as secondary absorbent layers in the management of heavily exuding wounds. Examples include Primapore® (Smith & Nephew), Mepore® (Mölnlycke) and absorbent cotton gauze (BP 1988).

2. Advanced wound dressings

Alginate dressings

Alginate dressings are highly absorbent and come in the form of calcium alginate or calcium sodium alginate, which can be combined with collagen. Alginates form a gel when in contact with the wound surface; this can be lifted off when the dressing is removed, or rinsed away with sterile saline. Bonding the alginate to a secondary viscose pad increases absorbency. Examples include: Curasorb (Covidien), SeaSorb (Coloplast) and Sorbsan (Unomedical).

Hydrogel dressings

Hydrogel dressings consist of cross‐linked insoluable polymers (i.e. starch or carboxymethylcellulose) and up to 96% water. These dressings are designed to absorb wound exudate, or rehydrate a wound, depending on the wound moisture levels. They are supplied in flat sheets, as an amorphous hydrogel, or as beads. Examples include: ActiformCool® (Activa) and Aquaflo® (Covidien).

Films (permeable film and membrane dressings)

Films (permeable film and membrane dressings) are permeable to water vapour and oxygen, but not to water or micro‐organisms. Examples include Tegaderm® (3M) and Opsite® (Smith & Nephew).

Soft polymer dressings

Soft polymer dressings are composed of a soft silicone polymer held in a non‐adherent layer, and are moderately absorbent. Examples include: Mepitel® (Mölnlycke) and Urgotul® (Urgo).

Hydrocolloid dressings

Hydrocolloid dressings are occlusive and usually composed of a hydrocolloid matrix bonded onto a vapour‐permeable film or foam backing. When in contact with the wound surface this matrix forms a gel to provide a moist environment for the wound. Examples include: Granuflex® (ConvaTec) and NU DERM® (Systagenix). Fibrous alternatives have been developed that resemble alginates and are not occlusive, but which are more absorbant than standard hydrocolloid dressings, for example, Aquacel® (ConvaTec).

Foam dressings

Foam dressings contain hydrophilic polyurethane foam and are designed to absorb wound exudate and maintain a moist wound surface. These are available in a variety of versions: some include additional absorbent materials, such as viscose and acrylate fibres or particles of superabsorbent polyacrylate, while others are silicone‐coated for non‐traumatic removal. Examples include: Allevyn® (Smith & Nephew), Biatain® (Coloplast) and Tegaderm® (3M).

Capillary‐action dressings

Capillary‐action dressings consist of an absorbent core of hydrophilic fibres held between two low‐adherent contact layers. Examples include: Advadraw® (Advancis) and Vacutx® (Protex).

Odour‐absorbent dressings

Odour‐absorbent dressings contain charcoal and are used to absorb wound odour. Often these types of wound dressings are used in conjunction with a secondary dressing to improve absorbency. An example of an odour‐absorbent dressing is CarboFLEX® (ConvaTec).

3. Anti‐microbial dressings

Honey‐impregnated dressings

Honey‐impregnated dressings contain medical‐grade honey, which is proposed to have antimicrobial and anti‐inflammatory properties and can be used for acute or chronic wounds. Examples include: Medihoney® (Medihoney) and Activon Tulle® (Advancis).

Iodine‐impregnated dressings

Iodine‐impregnated dressings release free iodine when exposed to wound exudate. The free iodine is thought to act as a wound antiseptic. Examples include Iodoflex® (Smith & Nephew) and Iodozyme® (Insense).

Silver‐impregnated dressings

Silver‐impregnated dressings are used to treat infected wounds, as silver ions are thought to have antimicrobial properties. Silver versions of most dressing types are available (e.g. silver foam, silver hydrocolloid, etc). Examples include: Acticoat® (Smith & Nephew) and Urgosorb Silver® (Urgo).

Other antimicrobial dressings

Other antimicrobial dressings are composed of a dressing impregnated with an ointment thought to have antimicrobial properties. Examples include: chlorhexidine gauze dressing (Smith & Nephew), Cutimed Sorbact® (BSN Medical), and a dressing impregnated with the anti‐microbial polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB).

4. Specialist dressings

Protease‐modulating matrix dressings

Protease‐modulating matrix dressings alter the activity of proteolytic (protein‐digesting) enzymes in chronic wounds. Examples include: Promogran® (Systagenix) and Sorbion® (H & R).

It is difficult to make an evidence‐informed decision of the best treatment regimen for patients, given the diversity of dressings available to clinicians (including variation within each type listed above). In a UK survey performed to determine treatments used for debriding diabetic foot ulcers, a wide range of treatments was reported (Smith 2003), and it is possible that a similar scenario is true for choice of dressing. A survey of Diabetes Specialist Nurses found that low/non‐adherent dressings, hydrocolloids and alginate dressings were the most popular for all wound types, despite a paucity of evidence for any of these dressing types (Fiskin 1996). However, several new, heavily‐promoted types of dressing have become available in recent years. Some dressings now have 'active' ingredients, such as silver, that are promoted as options to reduce infection, and thus possibly promote healing. As increasingly sophisticated technology is applied to wound care, practitioners need to know how effective these ‐ often expensive ‐ dressings are compared with more traditional dressings.

How the intervention might work

Animal experiments conducted over 40 years ago suggested that acute wounds heal more quickly when their surface is kept moist, rather than left to dry and scab (Winter 1963). A moist environment is thought to provide optimal conditions for the cells involved in the healing process, as well as allowing autolytic debridement (disposal of dead cells by the body), which is thought to be an important part of the healing pathway (Cardinal 2009). The desire to maintain a moist wound environment is a key driver for the use of wound dressings. Different wound dressings vary in their levels of absorbency, so a very wet wound can be treated with an absorbent dressing (such as an alginate dressing) that draws excess moisture away from the wound in order to avoid skin damage, whilst a drier wound can be treated with a more occlusive dressing to maintain a moist environment.

Why it is important to do this overview

Foot ulcers in people with DM are a prevalent and serious global issue. Treatment with dressings forms a key part of the treatment pathway when caring for such ulcers: there are many types of dressings that can be used, and these vary considerably in cost. Given the number of dressing types available, we considered the potential volume of data available to be too great for a single Cochrane review of dressings for foot ulcers in people with DM, although such reviews have previously been published. An early UK Health Technology Assessment review of different strategies to prevent and treat diabetic foot ulcers included 39 clinical trials of which six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluated dressings for the treatment of foot ulceration in people with DM (O'Meara 2000). The review did not find any evidence to suggest that one dressing type was more, or less, effective in terms of treating diabetic foot ulcers. The methodological quality of trials was poor and all were small. Only one comparison was repeated in more than one trial. Another systematic review, also out of date (Mason 1999), reported similar findings. More recently a systematic review was published on the effectiveness of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot (search date December 2006; Hinchliffe 2008a). This included only eight trials that looked at dressings (as well as further non‐randomised studies), and, again, did not identify any evidence that one dressing type was superior to another in terms of promoting ulcer healing. It is important to note that the review was very broad in its outlook, looking at other non‐dressing interventions, and that since its publication more than six years' worth of new literature has become available.

There are several Cochrane reviews that examine the effects of different dressing types on the healing of foot ulcers in people with DM, either as a single condition (Dumville 2013a; Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2013c; Dumville 2013d; Edwards 2010), or as part of a wider review of the effectiveness of a dressing (Storm‐Versloot 2010). However, there is a need to draw together all existing review evidence regarding the effectiveness of dressings for the treatment of this condition and to present these data to decision makers.

Current guidelines for the treatment of foot ulcers in people with DM maintain that clinical judgement should be used to select a moist wound dressing (e.g. Steed 2006). More recent National Institute of Clinical and Health Excellence (NICE) guidelines for inpatient management of diabetic foot problems concluded that, given there was no evidence that one dressing type was better than another in terms of healing these wounds, dressing choice “should take into account specialist expertise, clinical experience, clinical assessment of the wound, clinical circumstances, site of the ulcer, and patient preference, and should use the approach with the lowest acquisition cost” (NICE 2013).

Objectives

To summarize data from systematic reviews that contain randomised controlled trial evidence on the effectiveness of dressings to heal foot ulcers in people with diabetes mellitus (DM).

Methods

The conduct of this overview has been guided by the recommendations of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), including the recommendations for conducting overviews of reviews (Becker 2011).

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

Types of studies

We included:

Cochrane systematic reviews of RCTs of any dressing type (as defined in types of interventions section) in the treatment of foot ulcers in people with DM.*

Non‐Cochrane systematic reviews of RCTs of any dressing type in the treatment of foot ulcers in people with DM. However, to be included a non‐Cochrane systematic review had to be deemed to have employed a systematic approach including a comprehensive and detailed search strategy, have included only RCTs, have clear and relevant study selection criteria, and have assessed methodological features of the included studies and reported a synthesis of evidence (narrative only or narrative combined with statistical pooling).*

Mixed treatment comparison meta‐analyses. Mixed treatment comparison meta‐analyses were only eligible for inclusion in this overview when undertaken as part of/as a result of a systematic review including RCTs.*

*If reviews included other studies as well as RCTs (e.g. controlled clinical trials) they were investigated to see whether RCTs were presented separately within the analysis (for example as a sensitivity analysis). If so, these RCT data were included; if not, the review was excluded. If reviews had a wider participant inclusion criterion than foot ulcers (e.g. post‐operative foot wounds resulting from amputation), the presentation of included studies was investigated and a decision made regarding inclusion of the review. They were only included if data on foot ulcers were presented separately. Primary RCTs published since the included reviews but not yet included in them were excluded, in line with Cochrane guidance.

Types of participants

People of any age with either type 1 or type 2 DM who have a foot ulcer.

Types of interventions

We included dressing treatments, classified according to the BNF classification (BNF 2014), into four broad sub‐groups (Table 1). However, this list is not exhaustive, and, given the international perspective of this overview, we plan to include reviews of dressings that may not fall into the subgroups specified by the BNF. However, dressings that contain living cells (skin‐substitute dressings) were not included in this review as we consider these to be a separate class of treatment. Additionally, we excluded evaluations of topical applications. If a review focused on an intervention type that can be applied as a dressing, or a topical application (i.e. silver), we only considered sections of the review that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. We only considered dressings compared with a different dressing or no dressing, we did not include comparisons of dressings with adjunct therapies (e.g. hyperbaric oxygen, negative pressure wound therapy, etc).

1. Overview of dressing types.

| Basic wound contact dressings |

| Low adherence dressings and wound contact material Absorbent dressings |

| Advanced wound dressings |

| Hydrogel dressings Films: permeable film and membrane dressings Soft polymer dressings Hydrocolloid dressings Foam dressings Alginate dressings Capillary‐action dressings Odour‐absorbant dressings |

| Anti‐microbial dressings |

| Honey

Iodine

Silver PHMB (polyhexamethylene biguanide or polihexanide) Other |

| Specialist dressings |

| Protease‐modulating matrix |

Types of outcomes

Primary outcomes

Complete wound healing

Trialists measure and report wound healing in many different ways that include: time to complete wound healing, the proportion of wounds healed during follow‐up, and rates of change of wound size. For this review we regarded reviews that reported one or more of the two outcomes listed below as providing the best measures of outcome in terms of relevance and rigour.

Time to wound healing within a specific time period correctly analysed using survival, time‐to‐event, approaches ‐ ideally with adjustment for relevant co‐variates such as baseline size. We assumed that the period of time in which healing could occur was the duration of the trial, unless otherwise stated.

Number of wounds completely healed during follow‐up (frequency of complete healing), with healing being defined by the study authors.

Secondary outcomes

We extracted and reported only useful summary data, as defined below, for secondary outcomes.

Participant health‐related quality of life/health status (measured using a standardised generic questionnaire such as EQ‐5D, SF‐36, SF‐12 or SF‐6 (Dolan 1995; Ware 2001), or wound‐specific questionnaires such as the Cardiff wound impact schedule (Price 2004), at noted time points. We did not include ad hoc measures of quality of life that were likely not to be validated, and not common to multiple trials.

Adverse events where a clear methodology for the collection of adverse event data had been provided. We summarized adverse event data only when it was clear that the participant (or wound) was the denominator. That is, data were presented so that the number of events per participant are known (or an overview of this, e.g. number of participants with one or more event). Conversely, where the potential for multiple count data per participant could not be assessed, we did not consider data further. Finally, we noted the method of data collection, and commented on the potential risk of measurement and performance bias.

Resource use (including measurements of resource use such as number of dressing changes, nurse visits, length of hospital stay and re‐operation/intervention).

Dressing performance such as exudate management or patient comfort on dressing removal.

Search methods for identification of reviews

For this overview we searched the following electronic databases to identify both Cochrane and non‐Cochrane systematic reviews and reports of mixed treatment comparisons.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 4);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 1);

Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to 14 April 2015);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, 14 April 2015);

Ovid EMBASE (1980 to 14 April 2015);

We used the following search strategy to identify Cochrane and non‐Cochrane systematic reviews in The Cochrane Library (which includes DARE ‐ a repository of structured, critical summaries of published systematic reviews):

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Occlusive Dressings] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Bandages, Hydrocolloid] explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor: [Biological Dressings] explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor: [Alginates] explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor: [Hydrogels] explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor: [Silver] explode all trees152 #7 MeSH descriptor: [Silver Sulfadiazine] explode all trees #8 MeSH descriptor: [Honey] explode all trees #9 (dressing* or hydrocolloid* or alginate* or hydrogel* or "foam" or "bead" or "film" or "films" or tulle or gauze or non‐adherent or "non adherent" or silver or honey or matrix):ti,ab,kw #10 {or #1‐#9} #11 MeSH descriptor: [Foot Ulcer] explode all trees #12 MeSH descriptor: [Diabetic Foot] explode all trees #13 (diabet* near/3 ulcer*):ti,ab,kw #14 (diabet* near/3 (foot or feet)):ti,ab,kw #15 (diabet* near/3 wound*):ti,ab,kw #16 (diabet* near/3 amputat*):ti,ab,kw #17 {or #11‐#16} #18 #10 and #17

We also used the search strategy designed by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, York, UK to identify the systematic reviews summarised in DARE. This strategy is shown in Appendix 2 and was used to identify non‐Cochrane systematic reviews in Ovid MEDLINE, particularly those systematic reviews not yet indexed on DARE. We have also developed a provisional search strategy intended to identify reports of mixed treatment comparison meta‐analysis in Ovid MEDLINE (Appendix 3). Both Ovid MEDLINE search strategies were also adapted for Ovid EMBASE.

We handsearched the Cochrane Wounds Group list of reviews via the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to ensure that all relevant reviews had been identified. During the conduct of this overview it was possible that the Cochrane Reviews included might be updated. For this reason we conducted this search several times during the review process to ensure that the most up‐to‐date versions of each review were included. We contacted relevant review authors for information, where necessary.

We did not restrict searches by language, date of publication or study setting.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of reviews

Two overview authors screened review titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant inclusions. The same two overview authors screened the full text of all potentially relevant sources for inclusion in the overview. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third overview author.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data into a pre‐defined and piloted data extraction form to ensure consistent data capture from each review. Data were extracted by one overview author and independently checked by a second, with a third acting as arbitrator where required. For each included review we extracted the following data:

study identification, authors' details;

review objectives;

search strategies, including search dates;

study inclusion and exclusion criteria;

included settings;

included populations;

all relevant comparisons;

the number of relevant included RCTs;

outcomes reported and details of reported outcome values;

method and results of risk of bias/quality assessment.

Where a comparison was included in more than one review, its details were recorded multiple times; as it was relevant to each review in which it is contained. If any information from a review was unclear or missing, we accessed the published reports of the individual trials. We did not contact trial authors for details of missing data, but rather assumed that reviewers had done all they could to retrieve the data. We entered data into Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

As discussed in the Cochrane Handbook, two overview authors independently assessed the methodological quality of included reviews using the 'assessment of multiple systematic reviews' (AMSTAR) instrument (Shea 2007), which is composed of the following 11 criteria:

Was an a priori design provided?

Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction?

Was a comprehensive literature search performed?

Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion?

Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided?

Were the characteristics of the included studies provided?

Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented?

Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions?

Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate?

Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed?

Was the conflict of interest stated?

The response to each criterion can be 'yes' (clearly done), in which case the criterion will be given a score of 1; 'no' (clearly not done); 'can't answer', or 'not applicable', based on the published review report. We rated a review with an AMSTAR score of 8 to 11 as one of high quality; a score of 4 to 7 as medium quality, and a score of 3 or less as low quality (Shea 2007). Disagreements between overview authors were discussed and resolved through consensus.

Quality of evidence in included reviews

We also report a summary of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment carried out for each trial in the most recent included review; this is given in the tables for each assessed comparison.

We had planned that two overview authors would use the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the most complete direct evidence for any pooled complete healing data (Atkins 2004). However, we did not undertake this process ‐ instead we used the GRADE assessment reported in one of the included reviews (Dumville 2012). The included review was conducted by one of the overview authors and checked independently by another author on that review. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality for RCTs:

high quality for randomised trials;

moderate quality for downgraded randomised trials;

low quality for double‐downgraded randomised trials;

very low quality for triple‐downgraded randomised trials.

We also reported the results of an ad hoc quality assessment undertaken by study authors for quality assessment of network meta‐analysis estimates (Dumville 2012). This involved adapting the GRADE approach to allow the appraisal of mixed treatment comparison (MTC) estimates. Specific adaptations involved assessment of unexplained heterogeneity and inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence as one category of information. The modified approach also assessed the impact of sensitivity analysis on the estimate of effect. Relevant limitations in design and publication bias were applied to the estimates that particular direct links had contributed to.

Data synthesis

There are a number of different dressings for the treatment of foot ulcers in people with DM. To maximise value to the reader at this stage we presented a summary of current evidence for all available comparisons, taking account of any instances of overlap of evidence between reviews. Firstly each unique direct comparison for which relative treatment effect data are available is reported (e.g. gauze versus foam; foam versus alginate, etc) with any relevant indirect comparison data also summarised ‐ by outcome, where required. Subsequently, where availability of mixed treatment comparison meta‐analysis data resulted in comparisons informed only by indirect data, we have summarised these briefly. We considered the totality of evidence for each comparison, and reported summary of effect estimates as a narrative review. Thus, within each comparison, review data are presented in the following order:

direct pairwise analyses by source;

direct and indirect estimates;

indirect data only.

Where applicable, we aimed to convert relevant summaries to the risk ratio (RR) or hazard ratio (HR), although we were limited by the statistical information available in each included review. We did not plan or undertake re‐analysis of data beyond conversions to RR or HR.

In terms of presenting data, each individual included review, or mixed treatment comparison meta‐analysis, has been summarised using a Characteristics of included reviews table. We then present a summary overview of outcome data (by comparison) across reviews. We anticipated using forest plots and 'Summary of findings' tables to help present data; however, due to sparseness of data, we have presented only the latter.

Results

Description of included reviews

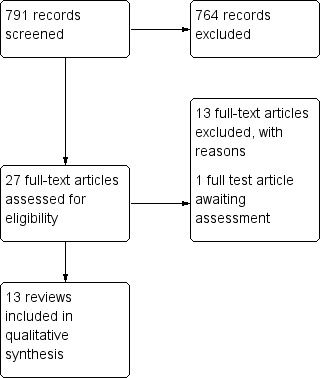

See Figure 1,for a summary of the review process. A summary of results in tabular format can be found at the end of the results section.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Cochrane systematic reviews

Following screening we identified eight potentially relevant Cochrane systematic reviews. Six of these were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria for this review (Dumville 2013a; Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2013c; Dumville 2013d; Edwards 2010; Storm‐Versloot 2010). We excluded the remaining two reviews as they did not contain any relevant included studies (Bergin 2006; Jull 2013). Of the six Cochrane reviews we included, five were focused specifically on foot ulcers in people with diabetes (Dumville 2013c; Dumville 2013a; Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2013d; Edwards 2010), and one focused more broadly on chronic wounds (Storm‐Versloot 2010). Four of the included Cochrane reviews investigated dressings specifically (Dumville 2013a; Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2013c; Dumville 2013d), and two investigated a wider group of interventions which included dressings. (Edwards 2010; Storm‐Versloot 2010).

Non‐Cochrane systematic reviews

Following screening we identified 19 potentially eligible non‐Cochrane reviews that we obtained as full text. Following further screening, we included seven of these reviews (Dumville 2012; Game 2012; Hinchliffe 2008b; Mason 1999a; Nelson 2006; O'Meara 2000; Voigt 2012), including one mixed treatment comparison meta‐analysis (all findings were produced from a fixed‐effect model; Dumville 2012). The remaining 11 reviews were excluded as they were not considered either to be systematic reviews or to be eligible for this overview (Ashton 2004; Bradley 1999; Braun 2014; Brimson 2013; Eddy 2008; Greer 2013; Heyer 2013; Holmes 2013; Jones 2009; Vandamme 2013; Wang 2005); one review is awaiting assessment as we are currently trying to obtained information about the included studies (Tian 2014).

Summary of included studies

We included a total of 13 reviews in this overview (see Table 2 for a summary of included reviews). None of the included reviews specified particular healthcare settings in their inclusion criteria, but three reviews explicitly noted that studies from any healthcare settings were included (Dumville 2012; Nelson 2006; Storm‐Versloot 2010). The methods used for assessing the quality or risk of bias of individual trials also varied between reviews. All Cochrane reviews followed the approach to risk of bias assessment that was in use at the time of the review. The approaches in the non‐Cochrane reviews varied (see Table 2).

2. Summary of included reviews.

| Review ID | Cochrane Review? | Number of databases searched | Search date | Interventions included | Included wound types | Other outcomes reported in the review that are relevant to this overview | Method of risk of bias/quality assessment used in the review |

| Dumville 2013d | Y | 6 | 2013 | Included any RCT in which the presence or absence of a hydrogel dressing was the only systematic difference between treatment groups | Foot ulcers in people of any age with DM | Health‐related quality of life; amputations; adverse events, including pain; cost | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) |

| Dumville 2013c | Y | 6 | 2013 | Included any RCT in which the presence or absence of a foam dressing was the only systematic difference between treatment groups | Foot ulcers in people of any age with DM | Health‐related quality of life; amputations; adverse events, including pain; cost | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) |

| Dumville 2013b | Y | 6 | 2013 | Included any RCT in which the presence or absence of a hydrocolloid dressing was the only systematic difference between treatment groups | Foot ulcers in people of any age with DM | Health‐related quality of life; amputations; adverse events, including pain; cost | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) |

| Dumville 2013a | N | 6 | 2013 | Included any RCT in which the presence or absence of a alginate dressing was the only systematic difference between treatment groups | Foot ulcers in people with DM | N/A | Standard GRADE assessment for direct estimates. Estimates from the MTC was assessed using an ad hoc modified version of GRADE developed by the study authors |

| Dumville 2012 | Y | 6 | 2012 | Included any RCT comparing one dressing treatment with another | Foot ulcers in people of any age with DM | Health‐related quality of life; amputations; adverse events, including pain; cost | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) |

| Edwards 2010 | Y | 6 | 2011 | Included any RCT comparing hydrogel dressing with good wound care or gauze | Foot ulcers in people with DM (neuropathic, neuroischaemic or ischaemic aetiology) | Number of complications/adverse events; quality of life | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) |

| Game 2012 | N | 6 | 2010 | Included any RCT comparing:

|

Foot ulcers in people with DM | Amputation | Each study was scored for methodological quality using scoring lists specific for each study design and based on checklists developed by the Dutch Cochrane Center (www.cochrane.nl/index.html) |

| Voigt 2012 | N | 2 | 2011 | Included any RCT comparing Hyalofill dressing with basic wound contact dressing | Foot ulcers in people with DM down to and including bone (Wagner class 4), diabetic and neuropathic lower extremity ulcers, venous leg ulcers, partial or full skin thickness burns, and surgical removal of the epithelial layer of skin | None | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) |

| Storm‐Versloot 2010 | Y | 6 | 2009 | Included any RCT comparing silver‐hydrofibre dressing with alginate dressing | Preventing infection or promoting the healing, or both, of uninfected wounds of any aetiology. People aged 18 years and over with any type of wound | Adverse events; pain; health related quality of life; length of hospital stay; costs | Standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment as outlined in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). |

| Hinchliffe 2008b | N | 4 | 2006 | Included any RCT comparing: basic wound contact dressing with alginate dressing or hydrofibre dressing or foam dressing | Chronic foot ulcers in people aged 18 years or older with either type 1 or type 2 DM | N/A | Each study was scored for methodological quality using design‐specific scoring, based on checklists developed by the Dutch Cochrane Center (www.cochrane.nl/index.html) |

| Nelson 2006 | N | 16 | 2002 | Included any RCT comparing hydrogel dressing with basic wound contact dressing | Foot ulcers in adults with DM | Number and duration of hospital admissions for diabetic foot problems | The methodological quality of RCTs was assessed using the Jadad (Jadad 1996) criteria |

| O'Meara 2000 | N | 19 | 2000 | Included any RCT comparing:

|

Chronic wounds, foot ulcers in people with diabetes, pressure ulcers, chronic leg ulcers (caused by venous, arterial or mixed insufficiency), pilonidal sinuses, non‐healing surgical wounds and chronic cavity wounds | N/A | Details of study quality assessment were provided in appendix 6. However the risk of bias assessment tool used in this review was not reported explicitly |

| Mason 1999a | N | 8 | Searched from 1983, but search date was not reported | Included any RCT comparing:

|

Foot ulcers in people with DM | N/A | Method of risk of bias/quality assessment was not reported explicitly in this study |

Abbreviations

MTC: Mixed Treatment comparison N: no N/A: Not applicable RCT: randomised controlled trial Y: yes

The included reviews provided direct evidence for 11 comparisons of dressings (listed below) to treat foot ulcers in people with diabetes. Since we included a mixed treatment comparison the majority of these comparisons were also informed by direct and indirect data. We present both direct only and mixed direct and indirect data where possible.

Note: one comparison (comparison 4 marked *) was informed by direct evidence only: all other comparisons were also informed by a combination of direct and indirect evidence as they were included in the mixed treatment comparison analysis (Dumville 2012).

Basic wound contact dressing compared with alginate dressing.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with hydrogel.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with hydrofibre dressing.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with Hyalofill*.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with iodine dressing.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with foam dressing.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with a protease‐modulating matrix dressing.

Foam dressings compared with alginate dressing.

Foam dressing compared with hydrocolloid (matrix).

Iodine‐impregnated dressing compared with hydrofibre dressing.

Alginate compared with silver‐hydrofibre/dressing.

We also summarize details on a total of 26 comparisons informed by indirect evidence only.

Comparisons informed by indirect evidence only

Basic wound contact dressing compared with silver‐hydrofibre dressing.

Basic wound contact dressing compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

Alginate dressing compared with hydrofibre dressing.

Alginate dressing compared with an iodine‐impregnated dressing.

Alginate dressing compared with hydrogel.

Alginate dressing compared with protease‐modulating matrix dressing.

Alginate dressing compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

Foam dressing compared with hydrofibre dressing.

Foam dressing compared with iodine‐impregnated dressing.

Foam dressing compared with hydrogel.

Foam dressing compared with a protease‐modulating matrix dressing.

Foam dressing compared with silver‐hydrofibre dressing.

Hydrofibre dressing compared with hydrogel.

Hydrofibre dressing compared with a protease‐modulating matrix dressing.

Hydrofibre dressing compared with silver‐hydrofibre dressing.

Hydrofibre dressing compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

Iodine‐impregnated dressing compared with hydrogel.

Iodine‐impregnated dressing compared with a protease‐modulating matrix dressing.

Iodine‐impregnated dressing compared with silver‐hydrofibre dressing.

Iodine‐impregnated dressing compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

Hydrogel compared with a protease‐modulating matrix dressing.

Hydrogel compared with silver‐hydrofibre dressing.

Hydrogel compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

Protease‐modulating matrix dressing compared with silver‐hydrofibre dressing.

Protease‐modulating matrix dressing compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

Silver‐hydrofibre dressing compared with matrix‐hydrocolloid dressing.

An overview of comparisons in tabular format: Numbered comparisons refer to analyses based on direct comparison data alone or direct plus indirect data.

| Basic dressing | Alginate | Hydrogel | Hydrofibre | Iodine‐impregnated | Foam | Protease‐modulating matrix | Matrix‐hydrocolloid | Silver‐hydrofibre | |

| Basic dressing | |||||||||

| Alginate | Comparison 1 | ||||||||

| Hydrogel | Comparison 2 | Indirect only | |||||||

| Hydrofibre | Comparison 3 | Indirect only | Indirect only | ||||||

| Hyalofill | Comparison 4 | ||||||||

| Iodine‐impregnated | Comparison 5 | Indirect only | Indirect only | Comparison 10 | |||||

| Foam | Comparison 6 | Comparison 8 | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | ||||

| Protease‐modulating matrix | Comparison 7 | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | |||

| Matrix‐ hydrocolloid | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Comparison 9 | Indirect only | ||

| Silver‐hydrofibre | Indirect only | Comparison 11 | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only | Indirect only |

Methodological quality of included reviews

We assessed the methodological quality of systematic reviews by using the measurement tool AMSTAR; ratings for each systematic review are presented in Table 3 for Cochrane reviews, and Table 4 for non‐Cochrane reviews. Assessment was undertaken by team members who were not authors on any included review.

3. AMSTAR assessment of included Cochrane reviews.

| AMSTAR criteria (for all included Cochrane reviews) | Storm‐Versloot 2010 | Edwards 2010 | Dumville 2013a | Dumville 2013b | Dumville 2013c | Dumville 2013d |

| A priori design | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Duplicate selection and extraction* | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Comprehensive literature search | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Searched for reports regardless of publication type or language | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Excluded/included list provided | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Characteristics of included studies provided | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Quality assessment of included studies assessed and presented | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Quality used appropriately in formulating conclusions | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Methods used to combine studies appropriate | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Publication bias assessed | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Conflict of interest stated | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Total score (out of a maximum of 11) | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

* In the AMSTAR assessment we coded “YES” where checking of study selections and data extraction was reported; we coded “NO” where only study exclusions were checked.

Abbreviations

N: no N/A: not applicable Y: yes

4. AMSTAR assessment of included non‐Cochrane reviews.

| AMSTAR criteria (for all included non‐Cochrane reviews) | O'Meara 2000 | Hinchliffe 2008b | Mason 1999a | Game 2012 | Nelson 2006 | Dumville 2012 | Voigt 2012 |

| A priori design | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Duplicate selection and extraction *1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Comprehensive literature search | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Searched for reports regardless of publication type or language | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Excluded/included list provided | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y |

| Characteristics of included studies provided | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Quality assessment of included studies assessed and presented | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Quality used appropriately in formulating conclusions | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Methods used to combine studies appropriate *2 | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y |

| Publication bias assessed | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NA | Y | Y |

| Conflict of interest stated *3 | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Total score (out of a maximum of 11) | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 |

*1. In the AMSTAR assessment we coded “YES” where checking of study selections and data extraction was reported; we coded “NO” where only study exclusions were checked

*2. In the AMSTAR assessment we coded the synthesis criterion as not applicable (N/A) for reviews where no meta‐analysis was conducted

*3. For the AMSTAR assessment we coded the funding criterion "NO" if funding for individual studies not reported

Abbreviations

N: no N/A: not applicable Y: yes

All the Cochrane reviews received high AMSTAR scores (ranged from 9 to 11), this could be as a result of following a generic protocol specifying methods; while the non‐Cochrane reviews also scored in the medium to high range (from 7 to 10).

Effect of interventions

We present data for the 11 comparisons informed by direct evidence from all reviews that included this comparison. In this way we highlight overlap of evidence between reviews and also highlight any differences in how data were reported between them. The majority of the comparisons that were informed by direct data evaluated complete wound healing as the primary outcome.

When reporting the evidence for each comparison, we have summarised the most complete and up‐to‐date data available. We present data using the RR if available, if the RR was not presented and could not be calculated we then present odds ratio (OR) estimates or the alternative measures available. We report 95% confidence intervals (CI) where reported. One included study reported 95% credible intervals (CrI), which we in turn report here; these are the Bayesian equivalent of CIs.

It is important to note that the reviews by Dumville et al have very consistent review protocols ( Dumville 2013a; Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2013c; Dumville 2013d;Dumville 2012). For the outcome number of ulcers/participants healed, these reviews treated participants missing from the analyses as not having had a healed wound. That is, the reviews made an assumption about missing data such that the missing participants were included in the denominator but not the numerator. Other reviews have conducted analysis with complete case data. Discrepancies in effect estimates may have resulted from these differences, and these have been flagged in the tables of extracted data that accompany each comparison below.

Comparison 1: basic wound contact dressing compared with alginate dressing

All extracted data reported in Table 5

5. Comparison 1: review data for basic wound contact dressing versus alginate dressing.

|

Comparison 1 Basic wound contact dressing versus alginate dressing | ||||||

| Review | Included trials (trials that reported secondary outcome data are marked with an asterisk*) | Wound healing | HRQoL | Adverse events | Resource use | Dressing performance |

|

Dumville 2013a Primary outcomes: time to ulcer healing; proportion of ulcers healed within specific time Cochrane review |

RCTs: 3 Total N = 191 Alginate: n = 109 BWC: n = 82 Ahroni 1993(n = 39)* Follow‐up: minimum 4 weeks Alginate: n = 20 BWC: n = 19 Donaghue 1998 (n = 75)* Follow‐up: 8 weeks Alginate: n = 50 BWC: n = 25 Lalau 2002 (n = 77) Follow‐up: 6 weeks, unclear if only 4‐week data analysed Alginate: n = 39 BWC: n = 38 |

% ulcers healed Pooled analysis (fixed‐effect) from 2 RCTs: RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.80); I² 27%; Chi² P value 0.24 Trial data reported Ahroni 1993 Alginate 5/20 (25%) vs BWC 7/19 (37%); RR 0.68 (95% CI 0.26 to 1.77) Donaghue 1998 Alginate 24/50 (48%) vs 9/25 (26%); RR 1.33 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.42) Mean time to healing (weeks) Trial data reported Donaghue 1998 Alginate 6.2 (SD 0.4) vs BWC 5.8 (SD 0.4) |

NR |

Trial data reported Amputations Ahroni 1993 4 (2/group) all after the 4‐week follow‐up Other AEs Ahroni 1993 Alginates: 6 (4 antibiotic treatment, 1 death, 1 septicaemia) vs BWC: 4 (3 antibiotic treatment, 1 death) AEs Donaghue 1998 6 events, not described, group allocation unclear Hospitalisation Ahroni 1993 Alginate 2; BWC 1 |

NR | NR |

|

Dumville 2012 Primary outcome: proportion of ulcers healed within specific time Mixed treatment comparison Non‐Cochrane review |

Direct estimate RCTs: 2 Total N = 114 Alginate: n = 70 BWC: n = 44 Ahroni 1993(n = 39)* Alginate: n = 20 BWC: n = 19 Donaghue 1998 (n = 75)* Alginate: n = 50 BWC: n = 25 |

% ulcers healed Pooled analyses (fixed‐effect) from 2 RCTs Direct estimate OR 1.26 (95% CrI 0.55 to 2.46) MTC estimate OR 1.29 (95% CrI 0.57 to 2.51) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Hinchliffe 2008b Primary outcome: proportion of ulcers healed Non‐Cochrane review |

RCTs: 2 Total N = 152 Alginate: n = 89 BWC: n = 63 Donaghue 1998 (n = 75)* Alginate: n = 50 BWC: n = 25 Lalau 2002 (n = 77) Alginate: n = 39 BWC: n = 38 |

% ulcers healed Trial data reported Donaghue 1998 Alginate: 48% of n = 50 BWC: 36% of n = 25 Lalau 2002 NR |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

O'Meara 2000 Primary outcome: % ulcers healed Non‐Cochrane review |

RCTs: 1 Total N = 75 Donaghue 1998 (n = 75)* Alginate: n = 50 BWC: n = 25 |

% ulcers healed Trial data reported Donaghue 1998 Alginate:24/44, BWC:9/17 OR 1.07(95% CI 0.36 to 3.25) Mean time to healing Trial data reported Donaghue 1998 Alginate: 43.4 ± 19.8 days BWC: 40.6 ± 21 days |

NR |

Trial data reported Donaghue 1998 No difference in the number or severity of reported adverse reactions between groups |

NR |

Trial data reported Donaghue 1998 Patients’ assessment of perceived efficacy favoured alginate compared to previous treatment |

|

Mason 1999a Primary outcome: % ulcer healed Non‐Cochrane review |

RCTs: 2 Total N = 114 Alginate: n = 70 BWC: n = 44 Ahroni 1993 (n = 39) Alginate: n = 20 BWC: n = 19 Donaghue 1998 (n = 75)* Alginate: n = 50 BWC: n = 25 |

% ulcers healed Trial data reported Ahroni 1993 Alginate 5/20 (25%) vs BWC 7/19 (37%) % wounds healed eventually (unspecified time) Ahroni 1993 Alginate: 12/20 (60%) BWC: 14/19 (74%) Donaghue 1998 Alginate: 24/44 (55%), BWC: 9/17 (53%) Mean time to healing Trial data reportedDonaghue 1998 Alginate 43.4 ± 19.8 days BWC: 40.6 ± 21 days |

NR |

Trial data reported Withdrawals Donaghue 1998 Alginate 12% vs BWC 32% |

NR | NR |

Abbreviations

AE: adverse event BWC: basic wound contact dressing CI: confidence interval CrI: credible interval HRQoL: health‐related quality of life MTC: mixed treatment comparison NR: not reported OR: odds ratio RCT: randomised controlled trial RR: risk ratio

| Review ID | Cochrane review? | AMSTAR Score | Included studies relevant to this comparison | ||

|

Donaghue 1998; n = 75 8‐week follow‐up Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias: unclear Risk of detection bias:unclear Risk of attrition bias: low |

Lalau 2002; n = 77 6‐week follow‐up Complete wound healing data reported? No Risk of selection bias: unclear Risk of detection bias: low Risk of attrition bias: high |

Ahroni 1993; n = 39 4‐week follow‐up (unclear if longer) Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias:unclear Risk of detection bias:high Risk of attrition bias:low |

|||

| Dumville 2013a | Yes | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Dumville 2012 | No | 9 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Hinchliffe 2008b | No | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| O'Meara 2000 | No | 9 | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Mason 1999a | No | 7 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

Direct data: complete wound healing

Two reviews (Dumville 2013a; Dumville 2012) pooled complete wound healing data from two studies (Donaghue 1998; Ahroni 1993; n = 114) that reported number of wounds healed over their six‐ and four‐week follow‐up times. In total 51% (36/70) of ulcers in the alginate group healed and 53% (23/44) of ulcers in the basic wound contact dressing group healed: RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.80 (fixed‐effect model; I² 27%). The direct estimate was classed as being of moderate quality using the GRADE assessment (Dumville 2012).

Direct and indirect data: complete wound healing

When direct and indirect data were considered for this comparison there was no evidence of a difference in the number of ulcers healed in the alginate group compared with the basic wound contact dressing group: OR 1.29, 95% CrI 0.57 to 2.51 (Dumville 2012). The study authors used an ad hoc method to assess the quality of the mixed treatment comparison outputs: this estimate was classed as being of moderate quality.

Direct data: secondary outcomes

Limited secondary outcomes were reported: Dumville 2013a noted that the Donaghue 1998 study reported six trial participants with adverse events, but it was not clear to which groups these participants belonged, and the adverse events were not described. The same review noted that Ahroni 1993 reported two amputations in each trial group along with six additional adverse events for the alginate‐dressed group and four in the basic wound contact dressing group.

Summary of findings: alginate dressing versus basic wound contact dressing

Data from two studies (pooled in two reviews) consistently suggest there is no evidence of a difference in ulcer healing between alginate and basic wound contact dressings. There was imprecision in estimates so that a difference favouring either alginate dressings or basic wound contact dressings cannot be ruled out. There are limited data available on other outcomes for this comparison.

Comparison 2: basic wound contact dressing compared with hydrogel

All extracted data reported in Table 6

6. Comparison 2: review data for basic wound contact dressing versus hydrogel dressing.

|

Comparison 2 Basic wound contact dressing versus hydrogel dressing | ||||||

| Review | Included trials (trials that reported secondary outcome data are marked with an asterisk*) | Wound healing | HRQoL | Adverse events | Resource use | Dressing performance |

|

Dumville 2013d Primary outcome: number of ulcers healed Cochrane review |

RCTs: 3 Total N = 198 Hydrogel: n = 89 BWC: n = 63 D’Hemecourt 1998 (n = 138)* Follow‐up: 20 weeks Hydrogel: n = 70 BWC: n = 68 Jensen 1998 (n = 31)* Follow‐up: 16 weeks Hydrogel: n = 14 BWC: n = 17 Vandeputte 1997 (n = 29)* Follow‐up: 12 weeks Hydrogel: n = 15 BWC: n = 14 |

Ulcers healed Pooled analysis (fixed‐effect) from 3 RCTs: RR 1.80 (95% CI 1.27 to 2.56); I² 0%; Chi² P value 0.77 Trial data reported D’Hemecourt 1998 Hydrogel: 25/70 vs BWC 15/68; RR 1.62 (95% CI 0.94 to 2.80) Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 11/14 vs BWC 6/17; RR 2.23 (95% CI 1.11 to 4.48) Vandeputte 1997 Hydrogel 14/15 vs BWC 7/14; RR 1.87 (95% CI 1.09 to 3.21) |

NR |

Trial data reported Participants with AEs D’Hemecourt 1998 Hydrogel: 19/70 (27%) vs BWC 25/68 (37%); RR 0.74 (95%CI 0.45 to 1.21) Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 3 vs BWC 4 Amputations Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 1 vs BWC 0 Infection‐related complications Vandeputte 1997 Hydrogel: 1/15 (7%) vs BWC 7/14 (50%); RR 0.14 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.01) NB unblinded assessment* |

Trial data reported Cost/day (USD) Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 7.01 versus BWC 12.28. Costs not collected/compared as part of full economic evaluation |

NR |

|

Dumville 2012 Primary outcomes: time to ulcer healing; ulcers healed within specific time Non‐Cochrane review |

Direct estimate RCTs: 3 Total N: 198 Hydrogel: n = 89 BWC: n = 63 D’Hemecourt 1998 (n = 138)* Hydrogel: n = 70 BWC: n = 68 Jensen 1998 (n = 31)* Hydrogel: n = 14 BWC: n = 17 Vandeputte 1997 (n = 29)* Hydrogel: n = 15 BWC: n = 14 |

% ulcers healed Pooled analyses Direct estimate: OR 3.10 (95% CrI 1.51 to 5.50) MTC estimate: OR 3.33 (95% CrI 1.65 to 6.11) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Edwards 2010 Primary outcome: number of wounds healed Cochrane review |

RCTs: 3 Total N: 198 Hydrogel: n = 89 BWC: n = 63 D’Hemecourt 1998 (n = 138)* Hydrogel: n = 70 BWC: n = 68 Jensen 1998 (n = 31)* Hydrogel: n = 14 BWC: n = 17 Vandeputte 1997 (n = 29)* Hydrogel: n = 15 BWC: n = 14 |

% ulcers healed Pooled analysis (fixed‐effect) from 3 RCTs: RR 1.84 (95% CI 1.30 to 2.61) Trial data reported D’Hemecourt 1998 Hydrogel: 25/70 vs BWC 15/68 Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 12/14 (85%) vs BWC 8/17 (46%)** Vandeputte 1997 Hydrogel 14/15 vs BWC 7/14 |

Pooled estimate of complications/AE from all 3 trials Hydrogel 22 events vs BWC 36 events. Fixed‐effect RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.95); random‐effects RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.25). I² 31% Trial data reported Infections D’Hemecourt 1998 Hydrogel 19/70 (27%) vs 25/68 (37%) RR 0.74 (95%CI 0.45 to 1.21)* Infection‐related complications Vandeputte 1997 Hydrogel: 1/15 (7%) vs BWC 7/14 (50%); RR 0.13 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.95)** Complications Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 2/14(14%) vs BWC 4/17 (24%); RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.13 to 2.84). Included events: amputation, increased eschar formation, cellulitis, worsened with increased eschar formation Pain D’Hemecourt 1998 Hydrogel: 11/70 (16%) vs BWC 10/68 (15%); RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.21 favouring BWC) unclear how pain reported |

|||

|

Hinchliffe 2008b Primary outcome: number of wounds healed Non‐Cochrane review |

Jensen 1998 (n = 31) Hydrogel: n = 14 BWC: n = 17 |

% wounds healed Trial data reported Jensen 1998 Hydrogel 12/14 (85%) vs BWC 8/17 (46%) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Nelson 2006 Primary outcome: number of wounds healed Non‐Cochrane review |

Vandeputte 1997 (n = 29)* Hydrogel: n = 15 BWC: n = 14 |

% wounds healed Trial data reported Vandeputte 1997 Hydrogel 14/15 (93%) vs BWC 5/14 (36%); RR 2.61 (95% CI 1.45 to 5.76) |

Trial data reported Vandeputte 1997 Amputation required Hydrogel 1/15 (7%) vs BWC 5/14 (36%); RR 5.4 (95% CI 0.98 to 32.7) Infection Hydrogel 1/15 (7%) vs BWC 7/14 (7%); RR 7.5 (95% CI 1.47 to 44.1) Antibiotics needed Hydrogel 1/15 (7%) vs BWC 14/14 (100%); RR 0.067 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.31) |

|||

*What Dumville defined as AE was all covered by infections in Edwards. Edwards noted that it was unclear how infection had been defined

**Events from the Jensen trial reported in Edwards differed from those reported in Dumville; so RR differs slightly. Checking the trial report showed that Dumville data seem accurate

Abbreviations

AE: adverse event BWC: basic wound contact dressing CI: confidence interval CrI: credible interval HRQoL: health‐related quality of life MTC: mixed treatment comparison NR: not reported OR: odds ratio RCT: randomised controlled trial RR: risk ratio USD: USA dollars

| Review ID | Cochrane review? | AMSTAR Score | Included studies relevant to this comparison | ||

|

D'Hemecourt 1998; n = 138 20‐week follow‐up Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias: unclear Risk of detection bias:unclear Risk of attrition bias: low |

Jensen 1998: n= 31 16‐week follow‐up Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias: unclear Risk of detection bias:unclear Risk of attrition bias: unclear |

Vandeputte 1997: n = 29 12‐week Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias: unclear Risk of detection bias:unclear Risk of attrition bias: unclear |

|||

| Dumville 2013d | Yes | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Dumville 2012 | No | 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Edwards 2010 | Yes | 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hinchliffe 2008b | No | 7 | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Nelson 2006 | No | 7 | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ |

Direct data: complete wound healing

Three reviews (Dumville 2013d; Dumville 2012; Edwards 2010) pooled data from the same three studies (198 participants), which had follow‐up times of 20, 16 and 12 weeks. Overall 85% (50/99) of ulcers in the hydrogel group healed (the Edwards 2010 review reported 51/99 for this group) and 28% (28/99) of ulcers in the basic wound contact group healed: RR 1.80, 95% CI 1.27 to 2.56 (fixed‐effect model; I² 0%) reported for Dumville 2013d, and RR 1.84, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.61(fixed‐effect model: I² 0%) reported by Edwards 2010. This suggests some evidence of an increase in the number of wounds healed in the hydrogel‐treated group, however the direct estimate was classed as being of low quality using the GRADE assessment (Dumville 2012).

Direct and indirect data: complete wound healing

When direct and indirect data were considered for this comparison there was evidence of an increase in the number of ulcers healed in the hydrogel group compared with the basic wound contact dressing group: OR 3.10, 95% CrI 1.51 to 5.50 (Dumville 2012). The study authors used an ad hoc method to assess the quality of the mixed treatment comparison outputs: this estimate was classed as being of very low quality.

Direct data: secondary outcomes

Dumville 2013d and Edwards 2010 summarised available data on adverse events, pain and infection from the three relevant trials. The Dumville 2013d review did not pool data, citing lack of methodological information on data collection methods for these outcomes. Edwards 2010 reported a total of 22 complications/events in the hydrogel groups, compared with 36 events in the comparison groups. These review authors pooled these trials suggesting evidence of an increase in adverse events/complications in the basic wound contact dressing group: RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.95 (fixed‐effect model; I² 31%). When a random‐effects model was applied, however, there was no longer evidence of a difference between groups: RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.25.

Summary of findings: hydrogel dressing versus basic wound contact dressing

Three recent reviews drew on the same three studies and reported evidence of an increase in the number of wounds that healed when treated with hydrogel compared with basic wound contact dressings, although this is judged as being low quality evidence. Heterogeneity in the data for adverse events means that the impact of hydrogel on these is unclear. The overall impact of hydrogel on ulcers is uncertain due to the low quality of the evidence.

Comparison 3: basic wound contact dressing compared with hydrofibre dressing

All extracted data reported in Table 7

7. Comparison 3: review data for basic wound contact dressing versus hydrofibre dressing.

|

Comparison 3 Basic wound contact dressing versus hydrofibre dressing | ||||||

| Review | Included trials (trials that reported secondary outcome data are marked with an asterisk*) | Wound healing | HRQoL | Adverse events | Resource use | Dressing performance |

|

Dumville 2013b Primary outcomes: time to ulcer healing; ulcers healed within specific time Cochrane review |

RCTs: 2 Total N: 229 Hydrofibre: n = 113 BWC: n = 116 Jeffcoate 2009 (n = 209)* Follow‐up: 24 weeks Hydrofibre: n = 103 BWC: n = 106 Piaggesi 2001 (n = 20)* Follow‐up: NR; maximum time reported approximately 350 days Hydrofibre: n = 10 BWC: n = 10 |

% ulcers healed Pooled analysis (random‐effects) from 2 RCTs: RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.38); I² 54%; Chi² P value 0.14 Trial data reported Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 46/103 (45%) vs BWC 41/106 (39%); RR 1.15 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.59) Piaggesi 2001 Hydrofibre 9/10 (90%) vs BWC 10/10 (100%); RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.18) Mean time to healing (days) Trial data reported Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 125.8 (SD 55.5) vs BWC 130.7 (SD 52.4) Piaggesi 2001 Hydrofibre 127 (SD 46) vs BWC 234 (SD 61) |

Trial data reported Jeffcoate 2009 No difference in disease‐specific or generic QoL |

Trial data reported Amputations Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 4 vs BWC 2 Piaggesi 2001 Hydrofibre 5 vs BWC 3 Serious AEs Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 28 vs BWC 35 Non‐serious AEs Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 227 vs BWC 244 AEs reported Piaggesi 2001 Hydrofibre 2 vs BWC 5 |

Trial data reported Cost per healed ulcer (GBP) Jeffcoate 2009 Hyrofibre 836 vs BWC 362 Days between dressing changes (mean) Piaggesi 2001 Hydrofibre 21 vs BWC 2.4 |

NR |

|

Dumville 2012 Primary outcomes: time to ulcer healing; ulcers healed within specific time Non‐Cochrane review |

Direct estimate RCTs: 2 Total N: 229 Hydrofibre: n = 113 BWC: n = 116 Jeffcoate 2009 (n= 209)* Hydrofibre: n = 103 BWC: n = 106 Piaggesi 2001 (n = 20)* Hydrofibre: n = 10 BWC: n = 10 |

% ulcers healed Pooled analyses Direct estimate: OR 1.28 (95% CrI 0.71 to 2.14) MTC estimate: OR 1.28 (95% CrI 0.72 to 2.13) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Game 2012 Primary outcome: number of wounds healed Non‐Cochrane review |

RCTs: 1 Total N: 209 Hydrofibre: n = 103 BWC: n = 106 Jeffcoate 2009 (n = 209)* Hydrofibre: n = 103 BWC: n = 106 |

% ulcers healed Trial data reported Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 44.7% vs BWC 38.7% Mean time to heal (days) Trial data reported Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre: 72.4 (SD 20.6) vs BWC 75.1 (SD 18.1) |

NR |

Trial data reported Secondary infection Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 54 vs BWC 48. Three‐way comparison reported as P value < 0.001 |

Trial data reported Mean dressing cost per patient (GBP) Jeffcoate 2009 Hydrofibre 43.60 vs BWC 14.85. Three‐way comparison reported as P value < 0.05 |

NR |

|

Hinchliffe 2008b Primary outcome: number of wounds healed Non‐Cochrane review |

RCTs: 1 Total N: 20 Hydrofibre: n = 10 BWC: n = 10 Piaggesi 2001 (n = 20) Hydrofibre: n = 10 BWC: n = 10 |

Time to heal (days) Trial data reported Piaggesi 2001 Hydrofibre: 127 (SD 46) vs BWC 234 (SD 25?) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

Abbreviations

AE: adverse event BWC: basic wound contact dressing CI: confidence interval CrI: credible interval GBP: British pounds (Sterling) HRQoL: health‐related quality of life MTC: mixed treatment comparison NR: not reported OR: odds ratio RCT: randomised controlled trial RR: risk ratio SD: standard deviation

| Review ID | Cochrane review? | AMSTAR Score | Included studies relevant to this comparison | |

|

Piaggesi 2001; n = 20 Max 350 days follow‐up Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias: unclear Risk of detection bias:unclear Risk of attrition bias: low |

Jeffcoate 2009: n = 209 24‐week follow‐up Complete wound healing data reported? Yes Risk of selection bias: low Risk of detection bias:low Risk of attrition bias: unclear |

|||

| Dumville 2013b | Yes | 10 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Dumville 2012 | No | 9 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Game 2012 | No | 7 | ✕ | ✓ |

| Hinchliffe 2008b | No | 7 | ✓ | ✕ |

Direct data: complete wound healing

Two reviews pooled data from two RCTs (n = 229) with 24‐week and 350‐day follow‐up respectively (Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2012). There was no evidence of a difference in the number of ulcers healed between the hydrofibre and the basic wound contact dressing treated groups with 49% (55/113) of ulcers in the hydrofibre group healed and 44% (51/116) of ulcers in the basic wound contact group healed: RR 1.01, 95% CI:0.74 to 1.38 (random‐effects model; I² 54%: Dumville 2013b; Dumville 2012). The direct estimate was classed as being of moderate quality using the GRADE assessment (Dumville 2012).

Direct and indirect data: complete wound healing

When direct and indirect data were considered for this comparison, again there was no evidence of a difference in the number of ulcers healed in the hydrofibre group compared with the basic wound contact group: OR 1.28, 95% CrI 0.71 to 2.13 (Dumville 2012). The study authors used an ad hoc method to assess the quality of the mixed treatment comparison outputs: this estimate was classed as being of moderate quality.

Direct data: secondary outcomes

Two reviews, Dumville 2013b and Game 2012, reported cost data from one study, Jeffcoate 2009, that suggested that the basic wound contact dressing was considered to be a more cost‐effective treatment than the hydrofibre dressing with the difference largely driven by the higher dressing costs in the hydrofibre group. Dumville 2013b reported data on the number of serious and non serious adverse events, summarising no evidence of a difference in these, nor in measures of health‐related quality of life, between the two groups. Game 2012 reported the number of secondary infections for the Jeffcoate 2009 study's three arms (also see comparison 5 and 10) alongside an overall P value of < 0.001 for the three‐way comparison (but did not specify which dressing(s) were superior). Further information was not presented on these data, but the review concluded, in contrast to the data presented, that there was no evidence of a difference in the incidence of secondary infection. Returning to the original study, Jeffcoate 2009, we confirmed that this is what the trial also concluded after a full analysis of the data, including the numbers of withdrawals and adjustment for the number of dressing changes.

Summary of findings: hydrofibre dressing versus basic wound contact dressing

Two recent reviews including data from two studies reported no evidence of a difference in the number of ulcers healed in hydrofibre and basic wound contact groups. The 95% CIs were wide and did not rule out an effect in either direction. Both reviews also reported the finding from one included study that basic wound contact dressings were a more cost‐effective treatment than hydrofibre dressing. One review reported no evidence of a difference in the number of serious and non serious events between groups, and one review reported no evidence of a difference in the number of secondary infections between hydrofibre and basic wound contact treated wounds.

Comparison 4: basic wound contact dressing compared with Hyalofill® dressing

All extracted data reported in Table 8

8. Comparison 4: review data for basic wound contact dressing versus Hyalofill dressing.

|

Comparison 4 Basic wound contact dressing versus Hyalofill dressing | ||||||

| Review | Included trials | Wound healing | HRQoL | Adverse events | Resource use | Dressing performance |

|

Voigt 2012 Primary outcome: number of ulcers healed Non‐Cochrane review |