Abstract

Aims

Sodium–glucose co‐transporter (SGLT)‐2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and heart failure (HF) hospitalization in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and high cardiovascular risk in two large clinical outcome trials: empagliflozin in EMPA‐REG OUTCOME and canagliflozin in CANVAS. The scope of eligibility for SGLT‐2 inhibitors (empagliflozin and canagliflozin) among patients with type 2 DM and HF, based on clinical trial criteria and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labelling criteria, remains unknown.

Methods and results

Using data from the US Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)—Heart Failure registry, we evaluated the proportion of patients with DM and HF eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitor therapy based on the clinical trial criteria and the US FDA labelling criteria. The GWTG‐HF registry is a quality improvement registry of patients admitted in hospital with HF in the USA. We included GWTG‐HF registry participants meeting eligibility criteria hospitalized between August 2014 and 30 June 2017 from sites fully participating in the registry. The initial inclusion time point reflects when both drugs had FDA approval. Among the 139 317 patients (out of 407 317) with DM hospitalized with HF (in 460 hospitals; 2014 to 2017), the median age was 71 years, 47% (n = 65 685) were female, and 43% (n = 59 973) had HF with reduced ejection fraction. Overall, 43% (n = 59 943) were eligible for the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial, 45% (n = 62 818) were eligible for the CANVAS trial, and 34% (n = 47 747) of patients were eligible for either SGLT‐2 inhibitors based on the FDA labelling criteria. Among the FDA‐eligible patients, 91.5% (n = 43 708) were eligible for either the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial or the CANVAS trial. Patients who were FDA eligible, compared with those who were not, were younger (70.0 vs. 72.0 years of age), more likely to be male (57.7 vs. 50.3%), and had less burden of co‐morbidities.

Conclusions

The majority of patients with DM who are hospitalized with HF are not eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitor therapies. Ongoing studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of SGLT‐2 inhibitors among patients with HF may potentially broaden the population that may benefit from these therapies.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus type 2, eligibility, heart failure, SGLT‐2 inhbitors

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one the most common co‐morbidities among patients with heart failure (HF).1 Patients with DM and HF, compared with those without DM, have distinct pathophysiological disease mechanisms and a higher risk of cardiovascular (CV) outcomes.2 Sodium–glucose co‐transporter (SGLT)‐2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce the risk of CV death and HF hospitalization in patients with type 2 DM and high CV risk in two large clinical outcome trials.3, 4 Both the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME and CANVAS trial randomized patients with type 2 DM and a history of CV disease to empagliflozin or canagliflozin, respectively, vs. placebo, and were associated with a reduction in CV mortality and in HF hospitalization.3, 4 Given the burden of CV and HF death among patients with type 2 DM,5 SGLT‐2 inhibitors may play an important role in reducing morbidity and mortality.6, 7 While the in‐hospital setting forms an ideal opportunity to optimize co‐morbidities,8, 9 patients with recent HF hospitalizations are frequently excluded from anti‐hyperglycaemic drug trials.10 There are key knowledge gaps regarding the scope of eligibility for SGLT‐2 inhibitors among patients with type 2 DM and HF, based on current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labelling criteria and EMPA‐REG OUTCOME and CANVAS trial eligibility criteria.

Aims

To address this knowledge gap, we used the Get With The Guideline—Heart Failure (GWTG‐HF) registry to (i) characterize patients' eligibility for SLGT‐2 inhibitors based on FDA labelling criteria and EMPA‐REG OUTCOME and CANVAS trial inclusion criteria; (ii) assess the scope of eligibility based on categories of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); and (iii) assess potential barriers to in‐hospital initiation of SGLT‐2 inhibitor therapy.

Methods

The GWTG‐HF registry is a national US quality improvement registry initiated in 2005 by the American Heart Association. Inclusion in the registry was permitted if patients were admitted for worsening HF or developed significant HF symptoms during a hospitalization. The following LVEF categories were used: HF with reduced EF (HFrEF) ≤ 40%; HF with mid‐range EF (HFmEF) 41–49%; and HF with preserved EF (HFpEF) ≥ 50%. Patients were considered to be FDA eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitors if they had HF and diabetes and met the following modified FDA drug labelling criteria11, 12: glomerular filtration rate (GFR) ≥ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 on either the admission or discharge and not on dialysis. Patients were eligible for the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial if they met the following modified trial inclusion criteria: (i) body mass index ≤45 kg/m2 and (ii) any of the following: history of prior myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident or transient ischaemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), history of ischaemic/coronary artery disease (CAD), in‐hospital PCI, in‐hospital PCI with stent, or in‐hospital CABG. Patients were considered eligible for the CANVAS trial if they met the following modified criteria: (i) age ≥30 years, (ii) any one of the following: prior myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident or transient ischaemic attack, CAD, peripheral vascular disease, PCI, CABG, ischaemia/CAD, HF history, in‐hospital PCI, PCI with stent, or CABG; and (iii) age ≥50 years with two or more of the following: systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg, cigarette smoker, history of renal insufficiency, or history of hyperlipidaemia. All other patients were considered non‐FDA and non‐trial eligible. Both trials had GFR > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 as inclusion criteria. FDA labelling criteria require patients to have a GFR > 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 prior to initiation of either drug.

We included GWTG‐HF registry participants meeting eligibility criteria hospitalized between August 2014 and 30 June 2017 (n = 139 317 out of 407 317; 34%) from sites fully participating in the registry. The initial inclusion time point reflects when both drugs had FDA approval. A sensitivity analysis was conducted based on patients with available haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) data (n = 8679).

Results

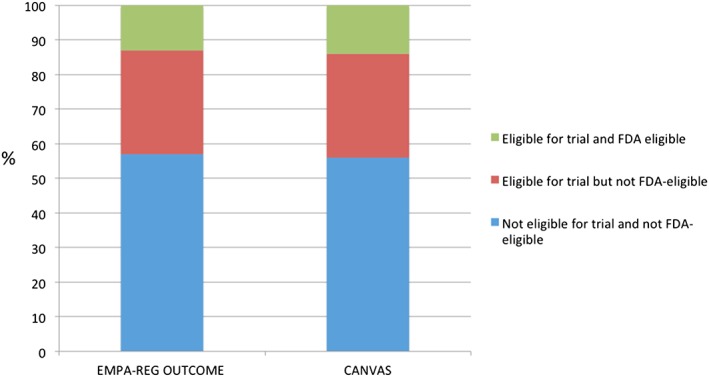

The median age of the entire cohort was 71 years, 47% (n = 65 685) were female, and 60.0% (n = 83 049) had a history of cardiac ischaemia. Among patients with recorded LVEF, 43% (n = 59 973) had HFrEF, 10% (n = 13 549) had HFmEF, and 45% (n = 62 777) had HFpEF. Overall, 43% (n = 59 943) of patients were eligible for the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial, 45% (n = 62 818) were eligible for the CANVAS trial, and 34% (n = 47 747) were eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitors based on the FDA labelling criteria (Figure 1 ). In total, 31% (n = 18 532) of patients eligible for the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial were not FDA eligible for empagliflozin. Similarly, 31% (n = 19 252) of patients eligible for the CANVAS trial were not FDA eligible for cangliflozin. Patients who were FDA eligible, compared with those who were not, were younger (70.0 vs. 72.0 years of age), more likely to be male (57.7 vs. 50.3%), and had less burden of co‐morbidities including anaemia (17.4 vs. 30.3%), prior HF (72.0 vs. 78.9%), and renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >2 mg/dL; 10.6 vs. 45.0%). The median LVEF was similar (43.0 vs. 45.0%). Patients who were eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitors also had less objective markers of severe HF, including lower B‐type natriuretic peptide (658 vs. 971 pg/mL) and higher haemoglobin (12.0 vs. 10.5 g/dL). Patients who were FDA eligible, compared with those who were not eligible, had a lower likelihood of peripheral vascular disease (12.3 vs. 16.3%), cerebrovascular accident/transient ischaemic attack (16.6 vs. 18.6%), and renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >2 mg/dL; 10.6 vs. 46.9%). Patients eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitors by FDA criteria, vs. those not eligible, were less likely to have history of ischaemic heart disease (55.5 vs. 60.4%). In addition, FDA‐eligible patients were more likely to be on an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (45.0 vs. 26.1%), angiotensin receptor blockers (18.9 vs. 14.9%), beta‐blockers (81.8 vs. 78.4%), and aldosterone antagonists (26.6 vs. 14.4%).

Figure 1.

Eligibility of sodium–glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitor therapies based on clinical trial and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) eligibility criteria.

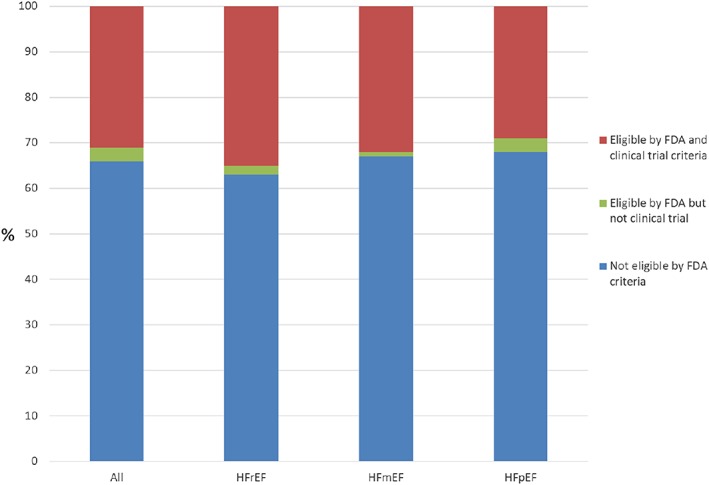

Among the FDA‐eligible patients, 91.5% (n = 43 708) were eligible for either the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial or the CANVAS trial. Similar trends among eligibility are seen in patients who have recorded HbA1c values (n = 6870; data not shown). Based on FDA labelling criteria, among patients with HF and DM, 37% (n = 22 424) of patients with HFrEF, 32% (n = 4416) of patients with HFmEF, and 32% (n = 20 269) of patients with HFpEF would be eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitors (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Eligibility of any sodium–glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitor therapy in patients hospitalized with heart failure and diabetes based on left ventricular ejection fraction. FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HFmEF, heart failure with mid‐range ejection fraction, EF 41–49%; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, EF ≥ 50%; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, EF ≤ 40%.

Conclusions

Our major findings are (i) 66% of patients with DM who are admitted in hospital with HF are not eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibitor therapy based on current FDA labelling criteria; (ii) 31% of patients eligible for the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME or CANVAS trial are not eligible for empagliflozin or canagliflozin by FDA labelling criteria; (iii) patients who are not eligible for SGLT‐2 inhibition by FDA criteria had more markers of more advanced HF; and (iv) the proportion of patients eligible by for SGLT‐2 inhibitors by FDA or clinical trial criteria declines among patients with HFmEF or HFpEF compared with HFrEF. The primary barrier to eligibility relates to renal dysfunction. National quality improvement programmes encourage the initiation and intensification of HF therapies during HF hospitalization.10 Clinical benefits with SGLT‐2 inhibitors in terms of HF hospitalizations and mortality reduction have emerged early in clinical trials. Further, in‐hospital initiation improves both adherence and long‐term persistence with therapy. However, the CANVAS and EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trials enrolled patients with GFR > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Based on earlier phase 2 studies, in the current FDA labelling criteria, SGLT‐2 inhibitors are not recommended to be initiated and to be discontinued if eGFR falls below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. Our study has limitations including the absence of detailed information on type 1 vs. type 2 DM, HbA1c on a majority of patients, and details information on anti‐hyperglycaemic therapies.

Given the high prevalence of renal dysfunction among patients with DM and HF across the world,13 a significant number of patients remain excluded from therapies with potential CV and HF benefit.

The EMPA‐REG OUTCOME and CANVAS trials have provided the initial evidence of CV efficacy among patients with DM and CV risk factors. Given the potential magnitude of benefit and potential scope of eligibility of SGLT‐2 inhibitors, more evidence is needed regarding the safety and efficacy of initiating these therapies during HF hospitalization and among patients with renal dysfunction. The CREDENCE trial demonstrated the safety and efficacy of reducing the risk of renal events and HF hospitalization among patients with type 2 DM and albuminuric chronic kidney disease.14 If additional ongoing CV outcome trials of SGLT‐2 inhibitors among patients populations with HF or chronic kidney disease demonstrate safety and clinical efficacy, the development of more inclusive FDA labelling criteria may arise and would broaden the population that may benefit from these therapies.

Conflict of interest

A.S. received support from 'Fonds de recherche du Québec ‐ Sante' Junior 1 Clinician Scientist Award, Bayer–Canadian Cardiovascular Society, Alberta Innovates Health Solution, Roche Diagnostics, and Takeda. A.D. received research support from the American Heart Association, Amgen, and Novartis as well as consultation fees from Novartis. G.M.F. received grant funding from NIH, AHA, Novartis, Amgen, and Merck and consultation fees from Novartis, Amgen, BMS, GSK, Myokardia, Medtronic, and Cardionomic. G.F. received consultation fees from Amgen, Janssen, Medtronic, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical. K.M.: https://med.stanford.edu/profiles/kenneth-mahaffey?tab=research-and-scholarship. J.A.E. received grants or honoraria from Novartis, Servier, Bayer, Merck, Trevena, Amgen, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Institutes of Health, and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. A.F.H. received honoraria from Amgen, Gilead, Janssen, Merck & Co., and Novartis and research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, and Portola.

Funding

This work was supported by an American Heart Association grant award #16SFRN30180010. The GWTG‐HF programme is provided by the American Heart Association. Quintiles is the data collection coordination centre for the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Get With The Guidelines programmes. The GWTG‐HF programme is provided by the American Heart Association. GWTG‐HF is sponsored, in part, by Amgen Cardiovascular and has been funded in the past through support from Medtronic, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho‐McNeil, and the American Heart Association Pharmaceutical Roundtable.

Sharma, A. , Wu, J. , Ezekowitz, J. A. , Felker, G. M. , Udell, J. A. , Heidenreich, P. A. , Fonarow, G. C. , Mahaffey, K. W. , Hernandez, A. F. , and DeVore, A. D. (2020) Eligibility of sodium–glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitors among patients with diabetes mellitus admitted for heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 274–278. 10.1002/ehf2.12528.

References

- 1. Sharma A, Zhao X, Bradley HG, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Felker GM, Yancy CW, Heidenreich PA, Ezekowitz JA, DeVore AD. Trends in non‐cardiovascular comorbidities among patients hospitalized with heart failure: insights from the Get With The Guidelines—Heart Failure Registry. Circ Heart Fail 2018; 11: e004646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharma A, Demissei BG, Tromp J, Hillege HL, Cleland JG, O'Connor CM, Metra M, Ponikowki P, Teerlink JR, Davidson BA, Givertz MM, Bloomfield DM, Dittrich H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Cotter G, Ezekowitz JA, Khan MAF, Voors AA. A network analysis to compare biomarker profiles in patients with and without diabetes mellitus in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19: 1310–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthew DR. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharma A, Green JB, Dunning A, Loknygina Y, Al‐Khatib SM, Lopes RD, Buse RD, Lachin JM, Van de Werf F, Armstrong PW, Kaufman KD, Standl E, Chan JCN, Distiller LA, Scott R, Peterson ED, Holman RR. Causes of death in a contemporary cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: insights from the TECOS trial. Diabetes Care 2017; 40: 1763–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fitchett DH, Udell JA, Inzucchi SE. Heart failure outcomes in clinical trials of glucose‐lowering agents in patients with diabetes. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 19: 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mosleh W, Sharma A, Sidhu MS, Page B, Sharma UC, Farkouh ME. The role of SGLT‐2 inhibitors as part of optimal medical therapy in improving cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2017; 31: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corra U, Cosyn B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FDR, Lochen ML, Lollgen H, Marques‐Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, Bart van der Worp H, van Dis I, Verschuren WMM. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2315–2381.27222591 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Schulte P, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Peterson ED, Krumholz HM. Medication initiation burden required to comply with heart failure guideline recommendations and hospital quality measures. Circulation 2015; 132: 1347–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma A, Bhatt DL, Calvo G, Brown NJ, Zannad F, Mentz RJ. Heart failure event definitions in drug trials in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4: 294–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/204629s000lbl.pdf (1 July 2018).

- 12. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/204042s000lbl.pdf (1 July 2018).

- 13. Cooper LB, Yap J, Tay WT, Teng THK, Macdonald M, Anand IS, Sharma A, O'Connor C, Kraus WE, Mentz RJ, Lam CS. Multi‐ethnic comparisons of diabetes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from the HF‐ACTION trial and ASIAN‐HF registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 1281–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW, CREDENCE Trial Investigators . Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2295–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]