Abstract

Past studies have revealed potential differences in the functional meaning and social evaluation of children’s temperamental shyness between Chinese interdependence-oriented and North American independence-oriented cultural contexts. However, very little is known about shy Chinese American children’s adjustment in Western school contexts and potential pathways underlying their adjustment. To address this gap in the literature, we examined the associations between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their social adjustment outcomes, including peer exclusion, prosocial behavior, and assertiveness/leadership skills. In addition, the mediating role of children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior and the moderating role of first-generation Chinese immigrant mothers’ encouragement of modesty in their parenting practices as applied to associations between temperamental shyness and social adjustment outcomes were explored. Path analyses indicated that the impact of Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness on their socio-emotional adjustment was mediated by their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior in school. However, when Chinese immigrant mothers encouraged their children to be more modest, children’s temperamental shyness was less strongly related to negative social adjustment outcomes through diminished anxious-withdrawn behavior. These results highlighted the importance of culturally-emphasized parenting practices in fostering Chinese American children’s adjustment in the U.S.

Keywords: Shyness, parents/parenting, social behavior, adjustment, culture

Temperamentally shy children desire interactions with peers but withdraw themselves due to a biologically-based disposition that is characterized by fear and anxiety in the face of novel situations (Asendorpf, 1991; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). These children remove themselves from the benefits of social interactions through the display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, or by behaving in a fearful, quiet, and reserved manner (Coplan & Armer, 2007). Shyness is consistently linked to social, emotional, and cognitive maladjustment outcomes in children, particularly in the North American cultural context (see Rubin & Coplan, 2010 for a review). However, findings on shy children’s adjustment in interdependence-oriented cultures, such as China, are less conclusive (Chen et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2015). Previous studies have suggested that variations in the developmental implications of shyness in independence- versus interdependence-oriented cultures reflect cultural differences in the functional meaning and social evaluation of shyness in the respective cultures (Chen, Wang, DeSouza, 2006; Xu, Farver, & Zhang, 2009). However, very little is known about the adjustment of shy immigrant children, such as Chinese American children, whose families have migrated from a more interdependent-focused to a more independent-focused culture, which could result in cultural evaluations of shyness that may differ inside versus outside of children’s homes.

Moreover, although researchers conceptualize temperamental shyness as a precursor of the display of shy and anxious-withdrawn behaviors, which in turn is linked to maladjustment (Rubin et al., 2009), no study to date has empirically tested whether anxious withdrawal mediates the associations between children’s shyness and their adjustment. Finally, mothers have been found to exacerbate or buffer shy children’s anxious-withdrawn behaviors depending on whether they employ negative (e.g., overprotective, authoritarian parenting) or positive (e.g., sensitive, supportive, warm) parenting practices; however, the moderating role of culturally-emphasized parenting practices has not yet been explored (see Rubin, Coplan, Bowker, & Menzer, 2004 for a review).

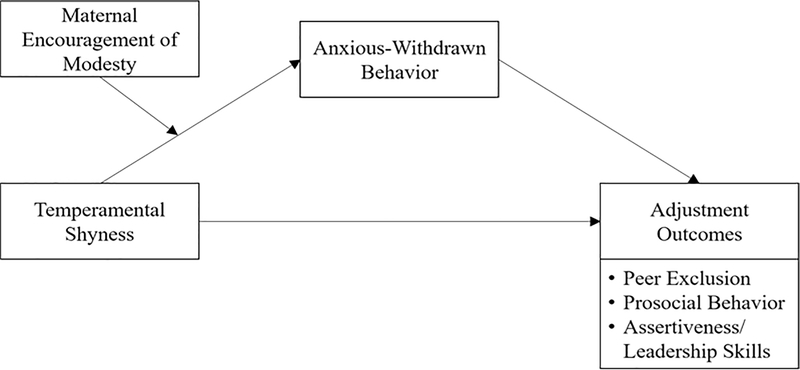

In order to address these gaps in the literature, the current study examined whether: (1) Chinese American children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behaviors mediated the association between their temperamental shyness and social adjustment outcomes (i.e., peer exclusion, prosocial behavior, assertiveness/leadership skills); and (2) maternal encouragement of modesty as a culturally-emphasized parenting practice of Chinese parents moderated the association between child temperamental shyness and anxious-withdrawn behaviors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The conceptual moderated mediation model.

Temperamental Shyness and Anxious Withdrawal

Children’s shyness is thought to arise from their biological and genetic propensity for increased fearfulness during social situations and has been linked to physiological indicators such as a hyperactivated amygdala, prefrontal EEG asymmetry, 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, more stable and increased heart rate, and higher levels of morning salivary cortisol (see Fox et al., 2015 for a review). Hence, shyness is considered a temperamental or physiological predisposition. In contrast to the biological bases of temperamental shyness, researchers have also examined the behavioral patterns of children who withdraw themselves from social interactions due to their fearfulness. Anxious withdrawal describes children’s observable behavioral responses, which reflect shy children’s internalized feelings of social anxiety and conflicted motivations of approach and avoidance (Coplan & Armer, 2007; Rubin et al., 2009). Temperamentally shy children may act upon their physiological dysregulation by displaying anxious-withdrawn behavior and behaving in a fearful, quiet, and reserved manner during social interactions.

Although temperamental shyness and anxious withdrawal share considerable conceptual similarities, researchers have argued that an inhibited and shy temperament in the presence of novel situations and social interactions is a natural precursor of observable anxious-withdrawn and socially reticent behavior (Rubin et al., 2009). Specifically, it has been posited that temperamentally shy children display anxious-withdrawn behavior, which in turn may put these children at risk for maladjustment given that their behavior is considered deviant or socially immature in a Western context (Rubin et al., 2009). Indeed, previous studies have indicated that both American and Chinese children who were temperamentally shy or behaviorally inhibited were more likely to display observable anxious behaviors in the presence of peers during later time points (Degnan, Henderson, & Rubin, 2008; Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002; Sun, Chen, & Zheng, 2006). Moreover, children’s display of anxious and fearful behavior, in turn, is associated with various adjustment outcomes, including peer exclusion and fewer prosocial behaviors and assertiveness/leadership skills (see Rubin & Coplan, 2010 for a review). However, despite theoretical models that elude to a mediational model and empirical findings supporting bivariate links among children’s temperamental shyness, their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, and their adjustment outcomes, no study to date has examined whether children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior mediates the associations between their temperamental shyness and their adjustment outcomes. The measurement of anxious withdrawal in this study centered on anxious, fearful, quiet, and reserved behavior that is typically considered as a behavioral manifestation of temperamental shyness.

The Role of Culture in Shy Children’s Social Adjustment

Temperamentally shy children who display anxious, fearful, quiet, and reserved behavior and remove themselves from social interactions are at greater risk for social maladjustment outcomes, including increased experiences of peer exclusion, decreased engagement in prosocial behavior, and a lack of assertiveness/leadership skills in North American independence-oriented cultural contexts (Coplan, Arbeau, & Armer, 2008; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Ladd, 2006; Young, Fox, & Zahn-Waxler, 1999; Findlay, Girardi, & Coplan, 2006; Chen, Rubin, & Sun, 1992; Rubin, Chen, & Hymel, 1993). Researchers have argued that shy children may be excluded or rejected by their peers because their anxious-withdrawn behaviors counter age-specific norms and expectations for social interactions and are perceived as incompetent or deviant (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Rubin et al., 2009). Moreover, shy children’s emotional dysregulation in social situations may interfere with their ability to engage in adaptive social interactions with others and ultimately lead to a decreased display of helpful, affiliative, and supportive actions as well as to lower levels of assertiveness or leadership skills (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998; Hastings, Rubin, & DeRose, 2005; Rubin et al., 2009).

However, findings regarding the social adjustment of shy Chinese or Chinese American children are less consistent. Specifically, older studies from China report shyness to be associated with greater peer acceptance, rather than rejection, and better leadership skills (Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1995; Chen, Rubin & Sun, 1992). Researchers attributed these variations to differences in the meaning and social evaluation of shyness in their respective cultural groups (Chen, 2010; Xu et al., 2009). In contrast to Western contexts, Eastern interdependent-focused cultures, such as China, may be more prone to regard shyness as less problematic and deviant given that shy, wary, and self-restraint behaviors are considered to reflect modesty, rather than a lack of maturity (Chen, 2010; Ho, 1986). Guided by Confucian and Taoist ideologies, these cultural values and appraisals of behavioral wariness in the traditional Chinese culture may shape positive attitudes and reactions towards shy children’s socially withdrawn behaviors, which in turn may lead to more positive adjustment (Chen et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2006). Although data from later cohorts of urban Chinese children and adolescents indicate either weaker or nonsignificant relations between shyness and positive social adjustment indices or even links with peer rejection and other social maladjustment indices due to increased Westernization in China (Chen et al., 2005; Hart et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2012; Xu, Farver, Chang, Zhang, & Yu, 2007), researchers still argue that shyness or some behavioral expressions of shyness may be less negatively perceived in Chinese cultures (Chen & Liu, 2016).

Importantly, very little is known about the adjustment of shy immigrant children. Previous studies of North American children indicated that developmental transitions might be particularly challenging for shy children given that it requires them to move from a familiar to an unfamiliar social context (Coplan et al., 2008; Early et al., 2002). In addition to these shared developmental transitions, it is important to examine the adjustment of shy children whose families have migrated from a more interdependence-focused (e.g., China) culture to a more independence-focused (e.g., United States; U.S.) culture because they may receive conflicting socialization messages about the acceptability of various behaviors from parents in the home environment and peers versus other socialization agents in the school context. The cultural fit issue may be particularly salient for young Chinese American children when they begin to transition from their familiar home context that values socially reserved behavior into a mainstream American school or preschool context that expects them to be socially assertive. Such conflicting socialization messages, in turn, may contribute to young Chinese American children’s engagement in anxious and socially withdrawn behaviors (Zhang Fang, Wu, & Wieczorek, 2014). Chinese American children may also be more likely to display anxious-withdrawn behavior due to their immigrant and minority status in the Western school context, for example because of negative interpersonal or discriminatory experiences in a Western school context due to differences in skin color, language accent, or cultural values (e.g., Lee & Thai, 2015). Thus, the current study focused on 3–6-year-old Chinese American children who may face these cultural and developmental challenges that may put them at heightened risk for adjustment difficulties.

Although Chinese American children are perceived to do well academically, much less attention has been paid to their early social-emotional competence (Cheah & Leung, 2011). These children may be at risk for experiencing social-emotional difficulties at school, including those of an internalizing nature (Liew, Castillo, Chang, & Chang, 2011; Yamamoto & Li, 2012). In fact, a recent meta-analysis by Krieg and Xu (2015) revealed that Asian heritage individuals report higher levels of social anxiety than those from European backgrounds. This finding is particularly important given that shyness shares significant conceptual similarity and is often considered as an early presentation of social anxiety in children (Rapee et al., 2005). However, only one published study to date has examined the implications of shyness among Asian American children, which revealed that anxiously shy Asian American children living in an Asian-concentrated region in the U.S. (Hawaii) were at an increased risk for maladjustment indices such as anxious behaviors, peer exclusion, and loneliness, as well as a decrease in engagement in prosocial behavior (Xu & Krieg, 2014). Despite accumulating risk factors that could undermine young shy Chinese American children’s adjustment and preliminary empirical evidence that indicates heightened risk for maladjustment, shy Chinese American children’s adjustment in the U.S. is understudied. The current study sought to address this gap and investigated shy Chinese American children’s social adjustment in a Western-concentrated school setting and potential mechanisms that may contribute to or undermine shy Chinese American children’s adjustment, including the aforementioned mediating role of children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior and the moderating role of parenting.

The Role of Parenting: Maternal Encouragement of Modesty

Recent efforts have focused on examining how parenting may moderate the association between temperamental shyness and displays of anxious-withdrawn behavior (Burgess, Rubin, Cheah, & Nelson, 2001). Overall, studies report that maternal negativity (e.g., overprotective, intrusive parenting) exacerbates children’s temperament shyness or fearfulness, whereas maternal positivity (e.g., warmth, positive structure) buffers against the negative effects of children’s temperamental shyness across multiple cultural contexts, including the U.S. and China (Chen et al., 2014; Coplan et al., 2008; Early et al., 2002; Grady & Karraker, 2014; Hane, Cheah, Rubin, & Fox, 2008; Hastings et al., 2008).

However, these studies have mainly focused on the moderating role of similar parenting practices across various cultural contexts. Yet, there are important cultural differences in how mothers perceive and react to their children’s shyness. Specifically, Chen and colleagues (1998) have reported that urban Chinese mothers have more positive and accepting attitudes towards their child’s shyness compared to European Canadian mothers. Moreover, Cheah and Rubin (2004) found that mainland Chinese mothers engaged in more teaching strategies in response to children’s social withdrawal than European American mothers, which may suggest that Chinese mothers are more likely to engage in parenting practices that may shape their child’s withdrawn behavior. Given these cultural differences in both mothers’ perceptions of and reactions towards children’s shyness, researchers have called for the examination of culturally-emphasized parenting practices in determining shy Chinese children’s adjustment and behavioral display of shyness (Xu, Zhang, & Hee, 2014). Accordingly, we investigated the moderating role of maternal encouragement of modesty, a culturally-emphasized parenting practice among Chinese parents, in the association between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their behavioral display of anxious-withdrawn behavior in this study.

Modesty is a central Confucian principle and is considered a key virtue in Chinese society that promotes group harmony by emphasizing the group’s accomplishments over individual interests and psychological attributes (Ho, 1986). Modesty is reflected in moderate, humble, and socially conforming behavior during interactions with others (Wu et al., 2002), including behaviors such as avoiding attention, effacing oneself, and enhancing others (Chen, Bond, Chan, Tang, & Buchtel, 2009). Previous studies have revealed that Chinese mothers highly encourage modesty in their children and continue to socialize their children in ways that emphasize their connectedness with others and minimize individual attributes even in contexts where the larger mainstream culture values independence over interdependence (Cai et al., 2011; Gorman, 1998; Wu et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2005).

We expected that Chinese American mothers who have more traditional views of shyness, as reflected in the modest, reserved, and exemplary behavior of a well-behaved child, may engage in more socialization practices that promote modest behavior in their children. Mothers’ more positive evaluations and encouragement of displaying modest behavior might convey their acceptance and valuing of temperamental shyness in their children and ultimately deflect these children from displaying anxious-withdrawn behavior. Indeed, Xu and colleagues (2014) argued that parents’ encouragement of modesty may reinforce shy children’s display of humble and unassuming behavior. However, no study to date has examined whether maternal encouragement of modesty may decrease temperamentally shy Chinese American children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior and in turn their risk for social maladjustment.

The Current Study

The first aim of the current study was to examine whether temperamental shyness was associated with Chinese American children’s social adjustment outcomes in a Western school setting with a focus on peer exclusion, prosocial behavior, and assertiveness/leadership skills. We expected temperamental shyness to be positively associated with peer exclusion, and negatively associated with prosocial behavior and assertiveness/ leadership skills.

Our second aim was to investigate whether children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior mediated the associations between their temperamental shyness and social adjustment outcomes. We hypothesized that temperamentally shy children would be reported as displaying higher levels of anxious-withdrawn behaviors, which in turn would be associated with greater adjustment difficulties in the school context.

Finally, we explored whether Chinese immigrant mothers’ encouragement of modesty parenting practices moderated or weakened the positive association between children’s temperamental shyness and display of anxious-withdrawn behavior. Given that mothers’ acculturation towards the mainstream American culture as well as children’s age and gender may be related to children’s social behaviors in the school context, we included maternal acculturation, child age and gender as covariates for the mediator and the outcome variables.

Method

Participants

Participants included 152 Chinese first-generation immigrant mothers (Mage = 37.60 years, SDage = 4.21 years) and their 3- to 6-year-old children (55% boys, Mage = 4.51 years, SDage = 0.91 years) living in the Maryland/Washington metropolitan area in the U.S. Chinese immigrant mothers had resided in the U.S. for an average of 10.15 years (SD = 5.72 years), were well-educated (95% college or graduate/professional degree, 4% partial college, 1% attended or completed high-school), and married (99% married, 1% married but separate or remarried). The preschool or daycare teachers of the participating children rated children’s experiences of peer exclusion, engagement in prosocial behavior, and display of assertive behaviors/leadership skills in the school setting.

Procedure

The participants were recruited from various organizations such as supermarkets, churches, and language schools upon receiving approval from these organizations. Mothers’ informed consent and children’s assent were obtained prior to data collection. Data were collected during home visits by trained bilingual research assistants. Participating Chinese immigrant mothers completed the questionnaires about their child’s temperamental shyness and their parenting practices in their preferred language. Furthermore, children’s teachers were asked to report on the child’s behaviors in social settings.

Measures

Temperamental Shyness

Children’s temperamental shyness was measure with the shyness subscale of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire, a widely used measure to assess 3- to 8-year-old children’s temperament (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). Mothers were asked to rate their child’s temperamental shyness (e.g., “acts shy around new people”) on a 7-point Likert scale using 10 items and response options ranging from 1 (extremely untrue) to 7 (extremely true) with higher scores indicating greater levels of temperamental shyness. A composite mean score was created for the temperamental shyness subscale, which showed very good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s α = .92). The CBQ has been validated across various cultures, including China (Rothbart et al., 2001).

Encouragement of Modesty

Mothers rated their encouragement of modest behaviors in their children using the 4-item encouragement of modesty subscale of the Chinese Parenting Practices Measure (Wu et al., 2002). Answer options were provided on a 5-point Likert scale and ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always) with higher scores reflecting greater maternal encouragement of their children to display modest and humble behaviors (e.g., “I discourage my child from showing off his/her skills”). A composite mean score of maternal encouragement of modesty was created. The internal consistency in the current sample was Cronbach’s α = .65. We also conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to further examine the psychometric properties of this instrument. Results of the CFA indicated that the one-factor model with 4 items showed a good fit with the data, χ2(1) = 1.75, p = .19, RMSEA =.07, SRMR =.02, CFI =.99, TLI =.94, with all items having factor loadings higher than the recommended minimum of .40 in the current sample with a range between .48 and .68, p < .001.

Anxious-Withdrawn Behavior and Social Adjustment Outcomes

Teachers were asked to report on children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior, prosocial behavior, assertiveness/leadership skills, and peer exclusion in a familiar peer setting by completing four subscales of the Teacher Behavior Rating Scale (TBRS; Hart & Robinson, 1996). The TBRS Scale is a battery of measures that tap into various dimensions of child behaviors. Teachers were instructed to rate the frequency of children’s behavior relative to other children in the same age group on a 3-point Likert Scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = very often). The anxious withdrawal (“[The child] is fearful in approaching other children; shies away when approached by other children; shows anxiety about being with a group of children”), prosocial behavior (e.g., “[The child] offers to share materials (e.g., pencils, erasers) when used in a task”), assertiveness/leadership skills (e.g., “[The child] leads out in peer activities”), and peer exclusion subscales (e.g., “[The child] is told to go away by other children”) consisted of 9, 5, 7, and 8 items and showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .86, 87, .92, .86), respectively. Composite mean scores were created for each subscale with higher scores reflecting higher levels of teacher-reported display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, peer exclusion, prosocial behavior, and assertiveness/leadership skills in the school context.

Maternal Acculturation

To control for the role of mothers’ acculturation level, Chinese American mothers’ behavioral acculturation towards the mainstream American culture was assessed with the Cultural and Social Acculturation Scale (CPAS-R; Chen & Lee, 1996). Mothers rated their frequency of engagement in social activities with Americans, English language use (e.g., speaking, writing, listening), and frequency of engagement in American lifestyle (e.g., celebration of holidays and festivals) on a 5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating greater acculturation. Sample items include, “How often do you read English novels or magazines” and “How often do you spend time with your Non-Chinese friends.” The CPAS-R showed adequate internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s α = .74). A mean score was created for the acculturation scale with higher scores indicating greater acculturation towards the mainstream American culture.

Data Analytic Plan

Path analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) using the Robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) estimation method. An interaction term between temperamental shyness and maternal encouragement of modesty was created by using the multiplicative term of the constructs. Moreover, the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 difference test (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) was used to evaluate whether the proposed moderated mediation model fit the data significantly better than a mediation model (i.e., model without interaction term). In addition, we calculated moderated mediation indices (Hayes, 2018) to determine the significance of the moderated mediation. In case of a significant moderated mediation, the simple effects of temperamental shyness on anxious-withdrawn behavior were tested at low (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), mean, and high levels (i.e., 1 SD above the mean) of maternal encouragement of modesty. Conditional indirect effects of temperamental shyness on the adjustment outcomes were also tested at the same values of maternal encouragement of modesty. The significance of conditional indirect effects was evaluated with 95% Bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) based on 10,000 bootstrap samples. Conditional indirect effects were deemed to be significant when a bootstrap CI did not include 0.

Results

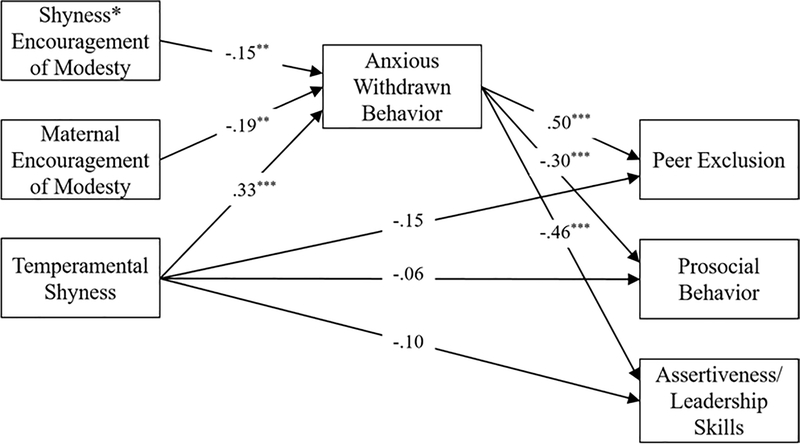

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the variables are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the model showed a very good fit with the data χ2(6) = 6.00, p = .42, RMSEA =.002 (90% CI = [.00, .11]), SRMR =.02, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00 and explained 23% of the variance in children’s display of anxious withdrawal, 22% of the variance in peer exclusion, 15% of the variance in prosocial behavior, and 29% of the variance in assertiveness/ leadership skills. The results of the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 difference test and fit indices of the moderated mediation and mediation models were summarized in Table 2 and revealed that the moderated mediation model fit the data significantly better than the mediation model, Satorra-Bentler Scaled Δχ2(Δdf = 1) = 7.40, p = .007. Consistently, the model fit indices also suggested a better fit with lower AIC, SBIC, RMSEA, and SRMR as well as higher CFI and TLI estimates for the moderated mediation model. Hence, the moderated mediation model was deemed as showing a better fit. In addition, moderated mediation indices were statistically significant for all three outcome variables (peer exclusion β = −.07, 95% Bootstrap CI [−.17; −.02]; prosocial behavior β = .04, 95% Bootstrap CI [.01; .10]; assertiveness/leadership skills β = .07, 95% Bootstrap CI [.01; .12], respectively). Hence, both the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 difference test and the moderated mediation indices suggested that the hypothesized moderated mediation model fit the data well and the moderated mediation was statistically significant. The statistical model diagram of the moderated mediation model with standardized path coefficients is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Bivariate Intercorrelations and Descriptive Information of Constructs

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Temperamental Shyness | – | ||||||||

| 2. Encouragement of Modesty | −.11 | – | |||||||

| 3. Anxious Withdrawal | .39*** | −.22** | – | ||||||

| 4. Peer Exclusion | .04 | −.15 | .44*** | – | |||||

| 5. Prosocial Behavior | −.16* | .15 | −.31*** | −.40*** | – | ||||

| 6. Assertiveness/Leadership | −.28*** | .13 | −.50*** | −.39*** | .77*** | – | |||

| 7. Maternal Acculturation | −.10 | .01 | −.20* | −.07 | .10 | .15 | – | ||

| 8. Child Age | −.15 | .03 | −.07 | −.05 | .06 | .13 | .06 | – | |

| 9. Child Gender | .11 | .03 | .11 | −.06 | .18* | .07 | −.08 | −.08 | – |

| M | 3.69 | 2.13 | 0.45 | 0.24 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 3.06 | 4.51 | 1.45 |

| SD | 1.18 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.91 | 0.50 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 2.

Model Fit Comparisons of the Moderated Mediation and Mediation Model Using the Satorra-Bentler Scaled Chi-Square Difference Test

| χ2 | c | df | AIC | SBIC | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | Satorra-Bentler Scaled Δχ2(Δdf) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderated Mediation | 6.00 | 0.83 | 6 | 1496.84 | 1492.32 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .002 | .02 | 7.40(1), p = .007 |

| Mediation | 11.66 | 0.79 | 7 | 1499.10 | 1494.73 | .98 | .93 | .066 | .04 |

Note. c = Satorra-Bentler scaling correction factor for MLR

Figure 2.

The moderated mediation model with standardized regression coefficient after controlling for the effects of maternal acculturation, child age, and child gender.

Note: **p<.01, ***p<.001. Effects presented in this figure represent direct effects between the variables. Conditional indirect effects were calculated at three levels of maternal encouragement of modesty presented in Table 3.

Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness was positively related to their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior (β = .33, p < .001) after controlling for maternal acculturation (β = −.15, p = .03), child gender (β = .14, p = .33), child age (β = .01, p = .95) as well as the main effect of maternal encouragement of modesty (β = −.19, p = .01) and its interactive effect with temperamental shyness (β = −.15, p = .01), such that higher levels of temperamental shyness predicted an increased display of anxious-withdrawn behavior. Children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, in turn, was positively associated with peer exclusion (β = .50, p < .001) and negatively associated with prosocial behavior (β = −.30, p < .001) and assertiveness/leadership skills (β = −.46, p < .001) after controlling for maternal acculturation, child gender, and child age in these associations. All of the associations between the covariates and the outcomes were nonsignificant (βs < .21, ps > .14) except the relations between child gender and prosocial behavior (β = .46, p = .002) and assertiveness/leadership skills (β = .29, p = .03).

However, Chinese immigrant mothers’ encouragement of modesty moderated the link between temperamental shyness and anxious withdrawal (β = −.15, p = .01), such that higher levels of maternal encouragement of modesty attenuated the positive relation between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their display of anxious-withdrawn behaviors (βlow = .47, p < .001, βmed = .33, p < .001, βhigh = .18, p = .04). Importantly, given that the interaction between maternal encouragement of modesty and child temperamental shyness is significant, the main effect of temperamental shyness on anxious-withdrawal is complex and depends on the levels of mothers’ encouragement of modesty.

Overall, the indirect effects of children’s temperamental shyness on their peer exclusion, prosocial behavior, and assertiveness/leadership skills through their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior were moderated by maternal encouragement of modesty (see Table 3 for a summary of conditional indirect effects). As suggested by significant conditional indirect effects, the associations between temperamental shyness with peer exclusion and leadership skills were significant at all levels of maternal encouragement of modesty. However, the indirect effects between temperamental shyness and prosocial behavior were only significant at low and mean levels of maternal encouragement of modesty. These findings indicate that the indirect relations between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their adjustment outcomes through their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior were attenuated with increasing levels of their mothers’ encouragement of modesty.

Table 3.

Summary of Conditional Indirect Effects for the Associations between Temperamental Shyness and Social Adjustment Outcomes through Anxious Withdrawal

| Outcome | Encouragement of Modesty | Indirect Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level |

β (SE) |

95% Bootstrap CI |

|

| Peer Exclusion | Low (− 1 SD) | .24 (.08) | [.12, .43] |

| Mean | .17 (.05) | [.09, .29] | |

| High (+ 1 SD) | .09 (.05) | [.02, .22] | |

| Prosocial Behavior | Low (− 1 SD) | −.14 (.05) | [−.26, −.03] |

| Mean | −.10 (.04) | [−.18, −.02] | |

| High (+ 1 SD) | −.06 (.03) | [−.15, .01] | |

| Assertiveness/Leadership | Low (− 1 SD) | −.22 (.06) | [−.34, −.11] |

| Mean | −.15 (.04) | [−.24, −.08] | |

| High (+ 1 SD) | −.08 (.05) | [−.19, −.01] | |

Finally, after controlling for the effects of anxious withdrawal, maternal encouragement of modesty, and the covariates of child gender, child age, and maternal acculturation, the direct effects between temperamental shyness and peer exclusion (β = −.15, p = .06), prosocial behavior (β = −.06, p = .45), and assertiveness/leadership (β = −.10, p = .17) skills were not significant, indicating that anxious withdrawal mediated the associations between children’s temperamental shyness and Chinese American children’s adjustment outcomes of peer exclusion, prosocial behavior and assertiveness/leadership skills.

Discussion

Little is known about the adjustment of shy Chinese American children, who are exposed to both interdependence and independence-oriented socialization influences in their daily lives (e.g., parents and peers in school, respectively). The current study sought to address this gap in the literature by examining the associations between Chinese American children’s shyness and their adjustment outcomes in school, including peer exclusion, prosocial behavior, and assertiveness/leadership skills, and the mediating role of their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior. In addition, we explored the role of culturally-emphasized parenting practice of encouragement of modesty as a potential buffer that might help deflect children from the behavioral display of shyness, and consequently to maladaptive outcomes.

Our results revealed that Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness was not directly, but indirectly and negatively related to their experiences of peer exclusion, display of prosocial behavior, and assertiveness or leadership skills in the classroom setting through their anxious-withdrawn behavior. In other words, as expected, Chinese American children with shy temperamental predispositions were more likely to display fearful and anxious-withdrawn behavior, which was in turn associated with being more excluded by their peers, displaying less prosocial behavior, and being less assertive or having fewer leadership skills among their peers. These findings suggest that it is not so much shy Chinese American children’s temperamental fearfulness during social interactions, but rather the behavioral enactment of their social wariness that puts them at risk for maladjustment in the American school context.

Researchers have previously posited that shy children’s behaviors are perceived to be socially incompetent and immature within a cultural context that values assertiveness and social initiative-taking (Chen, 2010). However, our study was the first to directly examine whether shy children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior mediates the associations between their temperamental disposition and their adjustment outcomes. In this regard, our results were consistent with previous studies and conceptualizations which linked temperamentally shy North American, Chinese, and Asian American children’s socially reticent and anxious behavior to maladjustment indices, including more peer exclusion, less prosocial behavior, and less assertiveness or leadership skills (Chen et al., 2006; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Hart et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2007). The present study further extended our knowledge of these processes in Chinese children living in a Western American context.

The second aim of the study was to examine whether Chinese immigrant mothers’ culturally-emphasized parenting practice, specifically their encouragement of modesty in their children, would buffer against the impact of children’s temperamental shyness on their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, which in turn might affect children’s psycho-social adjustment outcomes in an American independence-oriented school context. Consistent with previous research on the moderating role of positive parenting practices and characteristics (e.g., supportiveness, warmth, sensitivity, positivity) (Coplan et al., 2008; Early et al., 2002; Grady & Karraker, 2014; Hane et al., 2008), we found that Chinese immigrant mothers’ parenting may alleviate their temperamentally shy children’s interpersonal difficulties. Importantly, our study was unique in its focus on a culturally-emphasized parenting practice. Temperamentally shy children of first-generation Chinese immigrant mothers who reported the use of more encouragement of modesty were less likely to display anxious-withdrawn behavior, which ultimately was related to more positive socioemotional outcomes (i.e., less peer exclusion, more displays of prosocial behavior, and greater assertiveness or leadership skills).

Chinese immigrant mothers who engaged in more socialization practices that promote modest behaviors by socializing their children to emphasize the group’s accomplishments over individual interests and psychological attributes might have more traditional views of children’s dispositional shyness as reflecting modest, reserved, and exemplary behavior of a well-behaved child (Chen et al., 1998; Ho, 1986). These mothers likely have more positive evaluations and greater acceptance of their children’s shy temperamental disposition, and hence socialize their children towards displaying modest behaviors (e.g., avoiding attention, enhancing others, and effacing individual success and attributes) which decreases their tendency to display anxious behavior in social settings. Mothers’ encouragement of displaying humble and modest behavior may convey acceptance and valuing of children’s shy dispositions and perhaps socialize them towards regulating their temperament in a way that is not displayed in anxious and withdrawn behaviors. Indeed, Xu and colleagues (Xu & Farver, 2009; Xu, Farver, Chang, Zhang, & Yu, 2007; Xu, Farver, Yang, & Zeng, 2008; Xu et al., 2009) indicated that some shy Chinese children behave in an acquiescent, nonassertive, and unassuming manner during interactions with their peers rather than withdrawing themselves from social interactions. This form of regulated shyness has been differentiated from children’s anxiously withdrawn behavioral manifestations of their temperamental shyness (Xu et al., 2007). Relatedly, unlike our study Xu, Zhang, and Choo (2009) found a positive relation between encouragement of modesty and regulated shyness, but not anxious shyness/anxious withdrawal (as cited in Xu et al., 2014). As mentioned previously, anxious-withdrawn behavior displayed by immigrant children at school may partly result from negative experiences related to their immigrant and minority status (e.g., discrimination based on skin color or accent). In this regard, mothers’ encouragement of modesty may be particularly important as it represents cultural capital for immigrant and minority Chinese families in shaping the social experiences of shy Chinese American children.

Consistent with previous studies on Hispanic families (Gudiño & Lau, 2010), we also found that Chinese immigrant mothers who were more acculturated to the mainstream American culture had children who were less likely to display anxiously withdrawn behavior. More acculturated Chinese mothers may socialize their children in ways that are more congruent with American independence-oriented cultural values (Cheah, Leung, & Zhou, 2013), which may convey less conflicting socialization messages to children, promote their comfort in the mainstream cultural context, and reduce their anxious-withdrawn behavior in the classroom (Zhang et al., 2014).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be noted. First, the current study relied on cross-sectional data, which prohibits causal inferences and conclusions regarding the temporality of these effects (Jose, 2016; Selig & Preacher, 2009). Thus, we cannot rule out transactional, bidirectional, or interactional effects between children’s temperamental shyness and their behavioral display of anxious withdrawal. However, our study meets the six conditions that are required to justify a meaningful mediation analysis following Pieters’ (2017) guidelines, including (1) a theory-driven and empirically-grounded substantive foundation for the directionality of hypothesized paths, (2) reliability of measures, (3) controlling for important confounders, (4) distinctiveness of mediator and outcomes, (5) sufficient statistical power to detect small to moderate effects, and (6) statistically significant conditional indirect effects. Therefore, analyses in the current study were deemed meaningful, albeit findings from this study should be considered exploratory and used to guide the design of longitudinal studies that can assess the temporality and causality among these constructs, and replicate the conditional indirect effects found in the current study.

Second, we only controlled for Chinese immigrant mothers’ acculturation towards the mainstream American culture and did not examine mothers’ acculturation towards their heritage culture, and its effects on children’s display of anxious withdrawal and social adjustment. Emerging theories of acculturation, such as the specificity model of acculturation (Bornstein, 2017), emphasize the importance of conceptualizing acculturation as a much more differentiated and multidimensional process of changes. Relatedly, although we controlled for maternal acculturation towards the mainstream culture, we did not account for children’s acculturation-related factors, such as their English proficiency. Yet, less acculturated children likely face more discrimination because they may be less proficient in English and less accustomed to cultural expectations in the U.S. (Ying, Lee, & Tsai, 2000; Kim, Wang, Deng, Alvarez, & Li, 2011), which may lead to anxious-withdrawn behavior. Thus, more complete assessments of both maternal and child acculturation should be conducted in future research to more systematically explore their role in children’s socially withdrawn behavior and adjustment outcomes.

Third, our sample comprised middle-class first-generation Chinese Americans within Maryland/Washington and their 3–6-year-old children, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other samples with different sample characteristics. Hence, future research should examine these associations in Chinese American families of different SES backgrounds, 2nd and 3rd generation immigrants, and across different contexts in the United States.

Finally, similar to the general scientific inquiry on parenting, our study only focused on the buffering role of maternal practices in the associations between child shyness and social adjustment outcomes. However, given that paternal behaviors can be predictive of their shy children’s adjustment outcomes above and beyond the effect of maternal practices (e.g., Hastings et al., 2008), we recommend that future studies investigate the role of fathers’ socialization practices in shy Chinese American children’s adjustment.

Conclusion and Implications

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, this examination of shy Chinese American children’s adjustment as well as the impact of a culturally-emphasized parenting practice advanced our understanding in several ways. Our study examined the applicability of theories on shyness that were derived based on European and North American samples and demonstrated that temperamentally shy Chinese American children are at risk for maladjustment like their European-American peers. However, we also revealed that culturally-emphasized traditional Chinese values of socially reserved behavior and mothers’ encouragement of temperamentally shy children to display humble and modest behavior appeared to help decrease these children’s engagement in anxious-withdrawn behavior and ultimately decreased their risk for maladjustment in an independence-oriented American cultural context. Hence, our study shed light on the important role of culture in child development, and the benefits of Chinese immigrant parents’ maintenance of certain beliefs and practices from their culture of origin (Cheah, Leung, Zhou, 2013) for their shy children’s development.

Moreover, the current study has important implications on the conceptualization and measurement of shyness. By unveiling a potential mediating pathway through which Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness is linked to their social adjustment, we found empirical evidence that shy children’s behavior, rather than their temperamental disposition, is linked to an increased risk of experiencing social adjustment difficulties. Therefore, future studies should systematically distinguish between and measure the distinct effects of the two inter-related but distinct constructs of temperamental shyness versus the behavioral display of anxious withdrawal.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R03HD052827-01) awarded to Charissa S. L. Cheah, and the Marjorie Pay Hinckley Endowed Chair and the Zina Young Williams Card Professorship at Brigham Young University awarded to Craig H. Hart. We would like to thank the parents and children who participated in our study.

References

- Asendorpf JB. (1991). Development of inhibited children’s coping with unfamiliarity. Child Development, 62, 1460–1474. doi: 10.2307/1130819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (2017). The specificity principle in acculturation science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 3–45. doi: 10.1177/1745691616655997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess K, Rubin KH, Cheah CSL, & Nelson L (2001). Socially withdrawn children: Parenting and parent-child relationships In Crozier R & Alden LE (Eds.), The self, shyness and social anxiety: A handbook of concepts, research, and interventions. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Sedikides C, Gaertner L, Wang C, Carvallo M, Xu Y, & … Jackson LE (2011). Tactical self-enhancement in China: Is modesty at the service of self-enhancement in East Asian culture?. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 59–64. doi: 10.1177/1948550610376599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CS, & Leung CY (2011). The social development of immigrant children: A focus on Asian and Hispanic children in the United States In Smith PK, Hart CH (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood social development, (pp. 161–180). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CL, Leung CY, & Zhou N (2013). Understanding ‘tiger parenting’ through the perceptions of Chinese immigrant mothers: Can Chinese and U.S. parenting coexist?. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4, 30–40. doi: 10.1037/a0031217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SX, Bond MH, Chan B, Tang D, & Buchtel EE (2009). Behavioral manifestations of modesty. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40, 603–626. doi: 10.1177/0022022108330992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Liu CH (2016). Culture, peer relationships, and developmental psychopathology In Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, resilience, and intervention: Vol. 1. Theory and method (2nd ed) (pp. 723–769). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Lee B (1996). The Cultural and Social Acculturation Scale (Child and Adult Version). London, Ontario, Canada: Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Cen G, Li D, & He Y (2005). Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: The imprint of historical time. Child Development, 76, 182–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00838.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, DeSouza AT, Chen H, & Wang L (2006). Reticent behavior and experiences in peer interactions in Chinese and Canadian children. Developmental Psychology, 42, 656–665. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hastings PD, Rubin KH, Chen H, Cen G, & Stewart SL (1998). Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: A cross-cultural study. Developmental Psychology, 34, 677–686. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.6774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rubin KH, & Li Z (1995). Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 31, 531–539. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.4.531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rubin KH, & Sun Y (1992). Social reputation and peer relationships in Chinese and Canadian children: A cross-cultural study. Child Development, 63, 1336–1343. doi: 10.2307/1131559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhang G, Liang Z, Zhao S, Way N, Yoshikawa H, & Deng H (2014). Relations of behavioural inhibition with shyness and social competence in Chinese children: Moderating effects of maternal parenting. Infant and Child Development, 23, 343–352. doi: 10.1002/icd.1852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, & Armer M (2007). A ‘multitude’ of solitude: A closer look at social withdrawal and nonsocial play in early childhood. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00006.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA, & Armer M (2008). Don’t fret, be supportive! Maternal characteristics linking child shyness to psychosocial and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 359–371. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9183-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early DM, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Cox MJ, Saluja G, Pianta RC, Bradley RH, & Payne CC (2002). Maternal sensitivity and child wariness in the transition to kindergarten. Parenting: Science and Practice, 2, 355–377. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0204_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg Ν, & Fabes RA (1998). Prosocial development In Damon W (Series Ed.) & Eisenberg N (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional and personality development (5th ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay LC, Girardi A, & Coplan RJ (2006). Links between empathy, social behavior, and social understanding in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, & Ghera MM (2005). Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, & Ladd GW (2003). Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development, 17, 257–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JC (1998). Parenting attitudes and practices of immigrant Chinese mothers of adolescents. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 47, 73–80. doi: 10.2307/584853 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grady JS, & Karraker K (2014). Do maternal warm and encouraging statements reduce shy toddlers’ social reticence?. Infant and Child Development, 23, 295–303. doi: 10.1002/icd.1850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño OG, & Lau AS (2010). Parental cultural orientation, shyness, and anxiety in Hispanic children: An exploratory study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Cheah C, Rubin KH, & Fox NA (2008). The role of maternal behavior in the relation between shyness and social reticence in early childhood and social withdrawal in middle childhood. Social Development, 17, 795–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00481.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, & Robinson CC (1996). Teacher Behavior Rating Scale. Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, Yang C, Nelson LJ, Robinson CC, Olsen JA, Nelson DA, & … Wu P (2000). Peer acceptance in early childhood and subtypes of socially withdrawn behaviour in China, Russia and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 73–81. doi: 10.1080/016502500383494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Rubin KH, & DeRose L (2005). Links among gender, inhibition, and parental socialization in the development of prosocial behavior. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 51, 467–493. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2005.0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Sullivan C, McShane KE, Coplan RJ, Utendale WT, Vyncke JD (2008). Parental socialization, vagal regulation, and preschoolers’ anxious difficulties: Direct mothers and moderated fathers. Child Development, 79, 45–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF (1986). Chinese patterns of socialization: A critical review In Bond MH (Ed.), The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 1–37). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE (2016). The merits of using longitudinal mediation. Educational Psychologist, 51, 331–341. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1207175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Deng S, Alvarez R, & Li J (2011). Accent, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and perceived discrimination as indirect links between English proficiency and depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 47, 289–301. doi: 10.1037/a0020712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg A, & Xu Y (2015). Ethnic differences in social anxiety between individuals of Asian heritage and European heritage: A meta-analytic review. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6, 66–80. doi: 10.1037/a0036993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW (2006). Peer rejection, aggressive or withdrawn behavior, and psychological maladjustment from ages 5 to 12: An examination of four predictive models. Child Development, 77, 822–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, & Thai CJ (2015). Asian American phenotypicality and experiences of psychological distress: More than meets the eyes. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6, 242–251. doi: 10.1037/aap0000015Liew, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo J, L. G., Chang BW, & Chang Y (2011). Temperament, self-regulation, and school adjustment in Asian American children In Leong F, Juang L, Qin DB, & Fitzgerald HE (Eds.), Asian American and Pacific Island Children’s Mental Health, Vol. 1: Development and Context. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Chen X, Coplan RJ, Ding X, Zarbatany L, & Ellis W (2015). Shyness and unsociability and their relations with adjustment in Chinese and Canadian children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46, 371–386. doi: 10.1177/0022022114567537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Chen X, Li D, & French D (2012). Shyness-sensitivity, aggression, and adjustment in urban Chinese adolescents at different historical times. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00790.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters R (2017). Meaningful mediation analysis: Plausible causal inference and informative communication. Journal of Consumer Research, 44, 692–716. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucx081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, & Hart CH (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819–830. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hersey KL, & Fisher P (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, & Hastings PD (2002). Stability and social–behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development, 73, 483–495. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chen X, & Hymel S (1993). Socioemotional characteristics of withdrawn and aggressive children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 39, 518–534. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, & Coplan RJ (2010). The development of shyness and social withdrawal. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan R, & Bowker J (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A & Bentler PM (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66, 507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, & Preacher KJ (2009). Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Research in Human Development, 6, 144–164. doi: 10.1080/15427600902911247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Robinson CC, Yang C, Hart CH, Olsen SF, Porter CL, & … Wu X. (2002). Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 481–491. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, & Krieg A (2014). Shyness in Asian American children and the relation to temperament, parents’ acculturation, and psychosocial functioning. Infant and Child Development, 23, 333–342. doi: 10.1002/icd.1860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Farver JM, Chang L, Zhang Z, & Yu L (2007). Moving away or fitting in? Understanding shyness in Chinese children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology, 53, 527–556. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2008.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Farver JM, Yu L, & Zhang Z (2009). Three types of shyness in Chinese children and the relation to effortful control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 1061–1073. doi: 10.1037/a0016576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang L, & Hee P (2014). Parenting practices and shyness in Chinese children In Selin H (Ed.), Parenting across cultures: Childrearing, motherhood and fatherhood in non-Western cultures, (pp. 13–24). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Farver JM, Zhang Z, Zeng Q, Yu L, & Cai B (2005). Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, & Li J (2012). Quiet in the eye of the beholder: Teacher perceptions of Asian immigrant children In Garcia Coll C (Ed.), The impact of immigration on children’s development. Contributions to human development (Vol. 24, pp. 1–17). Karger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y, Lee PA, & Tsai JL (2000). Cultural orientation and racial discrimination: Predictors of coherence in Chinese American young adults. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 427–442. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young SK, Fox NA, & Zahn-Waxler C (1999). The relations between temperament and empathy in 2-year-olds. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Fang L, Wu Y, Wieczorek WF (2014). Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Chinese Americans: A study of immigration-related factors. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 201, 17–22. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827ab2e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]