Adhesion GPCR Gpr126/Adgrg6 regulates mouse body length and bone mass by controlling osteoblast differentiation.

Abstract

Adhesion G protein–coupled receptor G6 (Adgrg6; also named GPR126) single-nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with human height in multiple populations. However, whether and how GPR126 regulates body height is unknown. In this study, we found that mouse body length was specifically decreased in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice. Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblasts resulted in a remarkable delay in osteoblast differentiation and mineralization during embryonic bone formation. Postnatal bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength were also significantly affected in Gpr126 osteoblast deletion mice because of defects in osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and ossification. Furthermore, type IV collagen functioned as an activating ligand of Gpr126 to regulate osteoblast differentiation and function by stimulating cAMP signaling. Moreover,the cAMP activator PTH(1–34), could partially restore the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and the body length phenotype induced by Gpr126 deletion.Together, our results demonstrated that COLIV-Gpr126 regulated body length and bone mass through cAMP-CREB signaling pathway.

INTRODUCTION

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), also termed seven-transmembrane helix receptors, are the largest family of transmembrane proteins and are involved in a wide variety of physiological processes including bone development and remolding (1). The adhesion GPCR family, with 33 members, is the second largest subgroup of GPCRs. The defining characteristic of the adhesion GPCR family is their extraordinarily large N-terminal extracellular domain featuring various types of subdomains that are generally thought to communicate with the extracellular milieu and mediate their characteristic adhesive functions (1–3). The adhesion GPCR family member Gpr126 has been implicated in an increasing number of developmental defects. Multiethnic genome-wide association studies and human mutation analyses show that variations and mutations at the GPR126 locus are associated with multiple skeletal defects, including shortened height (4), adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) (5), arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (6), and periodontitis (7). In genetic studies of experimental animals, it has been reported that Gpr126 deletion in chondrocytes caused idiopathic scoliosis and pectus excavatum (PE), suggesting that Gpr126 in cartilage is the genetic cause for the pathogenesis of AIS (8). Furthermore, other studies reveal that Gpr126 is essential for myelination of axons in the peripheral nervous system (9), as well as in heart (10) and inner ear (11) development in mouse or zebrafish genetic animal models. However, whether GPR126 is a genetic cause for other diseases, including disorders of human height, is largely unknown.

Adhesion GPCRs have been reported to mediate cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions (12). Recently, type IV collagen (COLIV) was reported as an activating ligand for GPR126 in peripheral nerves and inner ear development, and Laminin-211 was described as another previously unidentified GPR126 ligand during Schwann cell development (13, 14). The prion protein is another agonistic ligand for GPR126 in myelination (15). All the reported ligands can induce a GPR126-dependent adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) response in cells and in animals, suggesting G protein–dependent signaling. Moreover, a peptide sequence (named the Stachel sequence) within the ectodomain of GPR126 can function as a tethered agonist to activate cAMP signaling (16). However, Gpr126 deletion in the chondrocyte lineage caused idiopathic scoliosis without affecting intracellular cAMP signaling, because treating these mice with rolipram, a known cAMP-positive regulator, could not reduce the incidence or severity of idiopathic scoliosis (8), suggesting that GPR126 could use different signaling pathways in different tissues.

Here, we study whether and how GPR126 regulated body height (length), an association that has been established in humans. Our mouse model results indicated that knockout (KO) of Gpr126 in osteoblasts, but not osteoclasts and chondrocytes, led to decreased body length and bone formation. Moreover, COLIV, but not Laminin-211, as an activating ligand of Gpr126, regulated osteoblast differentiation and function by stimulating cAMP signaling but not Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Furthermore, the osteoporosis drug PTH(1–34) [parathyroid hormone (1–34) peptide] could partially rescue the body length and bone mass phenotype induced by Gpr126 deletion in osteoblasts in vivo.

RESULTS

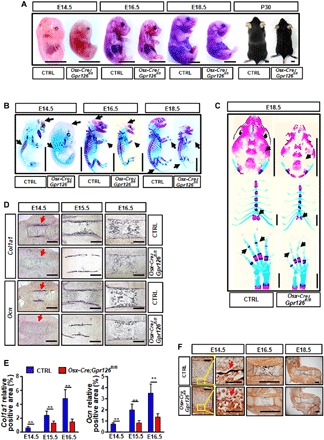

Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblasts caused a decrease in body length

To examine whether GPR126 regulates body height (length), we used three conditional mouse models (fig. S1). We knocked out Gpr126 in the osteoblast lineage (Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl) (Fig. 1A and fig. S2, A and D), osteoclast lineage (Lysm-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl) (figs. S2, B and E, and S3A), or chondrocyte lineage (Col2-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl) (figs. S2, C and F, and S3A). The results showed that only osteoblast-specific Gpr126 KO significantly decreased body length at embryonic (E) day 14.5 (E14.5), E16.5, and E18.5 and at postnatal (P) day P10 and P30 when compared with control littermates (Fig. 1A and fig. S2D). Together, only loss of Gpr126 in the osteoblast lineage, but not the osteoclast or chondrocyte lineages, resulted in a decrease in body length.

Fig. 1. Body length was decreased and embryonic bone formation was delayed in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice.

(A) Images of body size at embryonic (E) day 14.5 (E14.5), E16.5, and E18.5 and postnatal (P) day 30 (P30) of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and control (Ctrl) littermates. Scale bars, 5 mm. (B) Whole skeletal preparation of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates at E14.5, E16.5, and E18.5. Black arrows indicate the delayed Alizarin red staining (of bone) in the skull, ribs, and phalanges in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl embryos. Scale bars, 5 mm. (C) Body part skeletal preparation of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates at E18.5. Black arrows indicate the delayed Alizarin red staining (of bone) in the skull (top), sternum (middle), and phalanges (bottom) in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl embryos. Scale bars, 2 mm. (D) In situ hybridization analysis for expression of osteoblast differentiation markers collagen type I, alpha 1 (Col1a1) (top) and osteocalcin (Ocn) (bottom) in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and Ctrl littermate femurs at E14.5, E15.5, and E16.5. Red arrows indicate that the signal intensity was decreased in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl embryos. Scale bars, 200 μm. (E) Relative positive area of Col1a1 and Ocn in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and control littermate femurs at E14.5, E15.5, and E16.5 from in situ hybridization assay. **P < 0.01. n = 2 per group per time point. (F) Von Kossa staining analysis for bone mineralization in E14.5 (left), E16.5 (middle), and E18.5 (right) embryonic femurs of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and Ctrl littermates. Red arrows indicate that there was no signal at E14.5 in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl embryos. Scale bars, 100 μm (at E14.5, left), 50 μm (at E14.5, right), and 1 mm (at E16.5 and E18.5). Photo credit: Peng Sun, East China Normal University.

Osteoblast-specific Gpr126 deletion delayed embryonic bone formation by regulating osteoblast differentiation in vivo

To investigate how Gpr126 affects body length, we first examined bone development in embryonic mice. We analyzed skeletal preparations stained with Alizarin red for mineralized tissue and Alcian blue for cartilage at E14.5, E16.5, and E18.5. Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoclasts (Lysm-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl) or chondrocytes (Col2-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl) had little effect on bone development (fig. S3B). However, deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblasts (Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl) notably reduced the area of mineralized tissues. At E14.5, control littermate mice already exhibited bone formation in the skull and ribs, whereas there was little bone formation in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl embryos (Fig. 1B, black arrowheads). A remarkable delay in bone formation was also observed in the skull, tailbone, sternum, and phalanges at E16.5 and E18.5 in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (Fig. 1, B and C, black arrowheads).

Because bone formation is related to osteoblast differentiation and calcification, we next examined osteoblast differentiation marker gene expression and calcification status by in situ hybridization and von Kossa staining, respectively. Col1a1, a marker gene for early differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) to osteoblasts, and osteocalcin (Ocn), a marker gene for late stages of osteoblast differentiation, were reduced in the femurs of E14.5, E15.5, and E16.5 Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (Fig. 1, D and E). Specially, at E14.5, Col1a1 and Ocn began to be expressed in the femur bone collars of control mice; however, there was barely any expression signal in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (Fig. 1D, black signal, red arrowheads). Therefore, deletion of Gpr126 in the osteoblast lineage delayed osteoblast differentiation in embryonic bone development.

To examine whether Gpr126 affects bone formation, we compared the calcification status of control littermates and conditional KO (CKO) mice at E14.5, E16.5, and E18.5. We found that, compared with control littermates, the calcification profile of the femur bone collar was similar in both Lysm-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and Col2-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice at E14.5, E16.5, and E18.5 (fig. S3C). Calcification began at E14.5 in control littermate mice but was not seen in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl littermates (Fig. 1F, black signal, red arrowheads). Moreover, the mineralization signal was remarkably decreased in the Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl embryonic femur compared with control littermates at E16.5 and E18.5 (Fig. 1F).

To determine whether Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl specifically affected the osteoblast lineage, we examined osteoclast, chondrocyte, and hypertrophic chondrocyte development and activity in vivo and in vitro by histomorphology and cell culture analysis. Our data showed that deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblast lineage cells (Osx-Cre) had little effect on osteoclastogenesis (fig. S4, A and B) and osteoclast activity (fig. S4, C and D) between Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and littermate controls. Similarly, there was no notable difference in chondrocytogenesis (fig. S5, A and B) and hypertrophic chondrocyte marker expression (fig. S5, C and D) between Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and littermate controls. Together, all of the results indicate that only osteoblast differentiation and mineralization were delayed in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice but not in osteoclast or chondrocyte deletion mice.

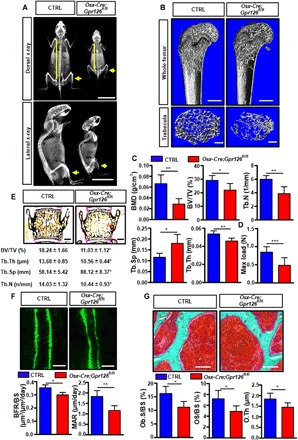

Gpr126 regulates bone mass by modulating bone formation and mineralization postnatally

It has been previously reported that conditional loss of Gpr126 in chondrocyte lineages results in mouse scoliosis and PE at P120 (8). X-ray analysis showed that scoliosis and PE were not present in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice at P120; however, the vertebral column was shorter (Fig. 2A, yellow line) and bone density decreased markedly (Fig. 2A, yellow arrowheads) in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice compared with control littermates. To elucidate the role of Gpr126 in regulating bone mass, we analyzed the bone characteristics of mice with Gpr126 deficiency in the osteoblast lineage using microcomputed tomography (μCT). There was a notable decrease of bone mineral density (BMD) and trabecular bone volume in the Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mouse femur compared with control littermates, as a consequence of decreased numbers of trabeculae and a reduction in trabecular thickness, while trabecular spacing was increased (Fig. 2, B and C). Next, we investigated whether Gpr126 regulates the mechanical properties of bone. Our results showed that the bone strength (as assessed by maximum load in humerus bones using the three-point bending test) of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice was remarkably reduced compared to control littermates (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Postnatal bone mass and bone strength were decreased in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice.

(A) Representative images of dorsal (top) and lateral (bottom) x-rays of 4-month-old mice (n = 3). Yellow lines indicate that the vertebral column was shorter in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice; yellow arrows indicate the decreased bone density in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice. Scale bars, 2 cm. (B) Representative μCT images of femurs from 1-month-old mice show the proximal femur (top; scale bars, 500 μm) and trabecular bone of the femur metaphysis (bottom; scale bars, 200 μm). (C) Quantitative μCT analysis of trabecular bone parameters of femurs from 1-month-old mice. BMD, bone mineral density; BV/TV, bone-volume/tissue-volume ratio; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n = 5. (D) Maximal loading (Max load) of humeral diaphysis from 1-month-old mice by three-point bending assay. n = 5. (E) Representative image of von Kossa staining of lumbar sections of 6-week-old mice (top) and trabecular bone parameters (bottom). Scale bars, 500 μm. n = 7. (F) Bone formation rate was decreased in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice. Representative images of calcein double labeling of the spinal trabecular bone of 6-week-old mice (top). Bone formation parameters from spinal sections of 6-week-old mice (bottom). BFR/BS, bone formation rate per bone surface; MAR, mineral apposition rate. Scale bars, 10 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n = 7. (G) Osteoid formation was suppressed in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice. Representative images of Goldner’s staining of 6-week-old mouse spinal trabecular bone. Spinal bone histomorphometric parameters. Ob.S/BS, osteoblast surface per bone surface; OS/BS, osteoid per bone surface; O.Th, osteoid thickness. Scale bars, 50 μm. *P < 0.05. n = 7.

To examine whether Gpr126 affects the mineralization of vertebral bone, we performed nondecalcified histomorphometric analysis of the vertebral body of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and control littermates at P40. We observed that there was a sharp decrease in trabecular bone volume in the Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice compared with control littermates as a consequence of decreased numbers of trabeculae, reduced trabecular thickness, and an increase in trabecular spacing (Fig. 2E). To determine whether the lower bone mass phenotype of the Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice was due to a decrease in bone formation and/or a decrease in osteogenesis, we next performed bone formation rate and osteoid analyses in the vertebral body. The bone formation rate was markedly reduced in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice by the calcein double labeling assay (Fig. 2F), and osteoid formation including osteoid volume, osteoid surface, and osteoid thickness significantly decreased, as assessed by Goldner’s staining (Fig. 2G). All of the results indicate that Gpr126 regulates bone mass by modulating bone formation and osteoblast mineralization.

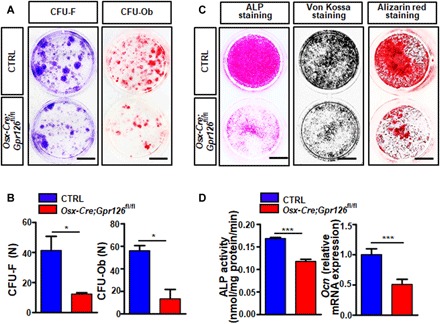

Gpr126 deficiency inhibited osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization

To examine whether Gpr126 affects BMSC differentiation to osteoblasts, we isolated BMSCs and analyzed osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization. Our data showed that Gpr126 deficiency significantly affected the formation of CFU-F (fibroblast colony-forming unit) and CFU-Ob (osteoblast colony-forming unit) colonies (Fig. 3, A and B). Similarly, Gpr126 deletion markedly suppressed osteoblast differentiation and mineralization [measured by alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining for the differentiation assay, as well as von Kossa staining and Alizarin red staining for the mineralization assay; Fig. 3C]. Furthermore, two osteoblast differentiation markers, ALP enzyme activity and Ocn expression, were decreased in Gpr126 deletion cells (Fig. 3D). Therefore, Gpr126 deletion impairs BMSC differentiation to osteoblasts.

Fig. 3. Gpr126 regulates osteoblast proliferationdifferentiation, and mineralization.

(A and B) Bone marrow stromal cell (BMSC) proliferation and differentiation were inhibited in Gpr126-deficient osteoblasts as determined by colony-forming unit (CFU) assay. BMSCs from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates were cultured for 14 days and then subjected to crystal violet staining (CFU-F, left) or Alizarin red staining (CFU-Ob, right). Representative images are shown (A). The number (n) of colonies per well for CFU-F and CFU-Ob was counted (B). Scale bars, 10 mm. *P < 0.05. n = 3. (C) BMSC differentiation and mineralization were suppressed in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts. BMSCs were isolated from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates and subjected to ALP staining (7 day), von Kossa staining (14th day), and Alizarin red staining (21st day) assays. Scale bars, 5 mm. (D) Gpr126 KO inhibited ALP enzyme activity (n = 5) and Ocn relative mRNA expression (n = 2) in osteoblasts. BMSCs were isolated from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates and differentiated into osteoblasts. The cells were harvested at days 7 and 14 of differentiation for ALP enzyme activity assay and Ocn mRNA quantitation by real-time PCR, respectively. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. n = 5.

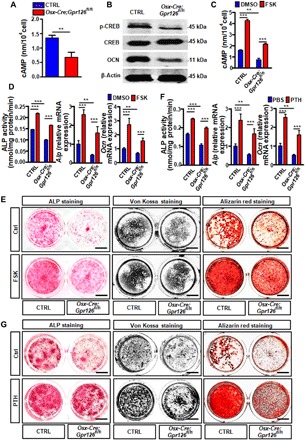

Deletion of Gpr126 suppressed osteoblast differentiation and mineralization by regulating the cAMP-CREB signaling pathway

Gpr126 is essential for peripheral myelination in Schwann cells (17), angiogenesis by regulating endothelial cell (18), and semicircular canal duct development in the zebrafish inner ear (11), all through the cAMP signaling pathway (19). It is established that, in osteoblastic cells, activation of the cAMP pathway ultimately promotes phosphorylation of the downstream effector cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB) to enhance osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of BMSCs; hence, cAMP-CREB signaling is one of the key pathways to regulate BMSC differentiation into osteoblasts (20). To examine whether Gpr126 regulates osteoblast differentiation and function by the cAMP signaling pathway in osteoblast cells, we measured cAMP concentrations after 14 days of differentiation from BMSCs to osteoblasts. Intracellular cAMP levels were significantly decreased in osteoblast cells from Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, phosphorylation of CREB was significantly decreased in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Gpr126 regulates osteoblast differentiation and function through the cAMP-CREB signaling pathway.

(A) Intracellular cAMP level was decreased in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts. BMSCs were isolated from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates and differentiated into osteoblasts. The cells were harvested and subjected to the cAMP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay at day 7 of differentiation. **P < 0.01. n = 3. (B) Western blot analysis of the p-CREB, CREB, and OCN levels in BMSCs from indicated mice after 14 days of osteoblast differentiation. (C) Intracellular cAMP level was restored in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts when treated with FSK. BMSCs were isolated from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates and differentiated into osteoblasts. The cells were treated with 10 μM FSK or vehicle control for 14 days, harvested, and subjected to the cAMP ELISA assay at day 14 of differentiation. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n = 3. (D) ALP enzyme activity (N = 5), ALP mRNA expression (n = 2), and OCN mRNA expression (n = 2) were restored in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts treated with 1 μM FSK. The cells were harvested and subjected to ALP enzyme activity assay (at day 14) or real-time PCR assay (ALP at day 7 and OCN at day14). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (E) Osteoblast differentiation and mineralization were rescued in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts when treated with FSK. BMSCs were isolated from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and control (Ctrl) littermates and differentiated into osteoblasts. ALP staining, von Kossa staining, and Alizarin red staining of BMSCs were performed after 7, 14, and 21 days of differentiation, respectively, while treated with or without 10 μM FSK. Scale bars, 5 mm. (F) ALP enzyme activity (N = 5), Alp mRNA expression (n = 2), and Ocn mRNA expression (n = 2) were restored in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts treated with PTH(1–34). The cells were harvested and subjected to ALP enzyme activity assay (at day 14) or real-time PCR assay (Alp at day 7 and Ocn at day14). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (G) Osteoblast differentiation and mineralization were rescued in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts when treated with PTH(1–34). BMSCs were isolated from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates and differentiated into osteoblast. ALP staining, von Kossa staining, and Alizarin red staining of BMSCs were performed after 7, 14, and 21 days of differentiation, respectively, while treated with or without PTH(1–34) (80 μg/kg). Scale bars, 5 mm.

To further confirm whether Gpr126 regulates osteoblast differentiation and mineralization by modulation of the cAMP-CREB signaling pathway, we used forskolin (FSK), an activator of adenylyl cyclase, and PTH(1–34), an osteoporosis drug, both of which can induce bone formation and mineralization by promoting cAMP-CREB signaling (21). Our results showed that the intracellular cAMP levels were decreased in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mouse osteoblasts, while FSK substantially increased the intracellular cAMP levels in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mouse osteoblast cells (Fig. 4C). As a result, ALP mRNA expression, enzyme activity, Ocn mRNA expression level (Fig. 4D), osteoblast differentiation, and mineralization (Fig. 4E) were rescued in Gpr126 deletion cells upon FSK treatment. Similar results were obtained upon treatment with PTH(1–34) (Fig. 4, F and G). Therefore, Gpr126 signals, at least in part, through cAMP/CREB to regulate osteoblast differentiation and function.

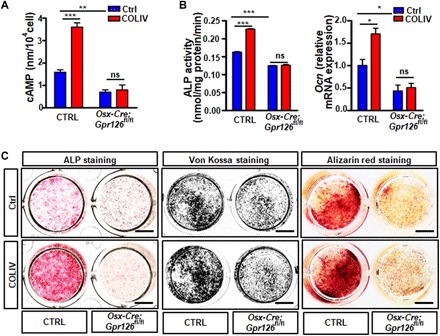

COLIV regulates osteoblast differentiation and function as an activating ligand of Gpr126 by stimulating cAMP signaling but not Wnt/β-catenin signaling

It has been previously reported that COLIV, a major structural component of the basement membrane, specifically binds to the extracellular N-terminal region of Gpr126 to stimulate the production of cAMP in some organs including bone (13). Our data showed that COLIV was expressed in both osteoblast and chondrocyte cells (fig. S6). To investigate whether COLIV acts as an activating ligand for Gpr126 and stimulates cAMP production in osteoblasts, we examined the intracellular cAMP levels in osteoblast cells from both Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mouse and control littermates after stimulating with COLIV. Our results showed that COLIV culture elevated intracellular cAMP concentrations in control osteoblast cells (Fig. 5A), whereas it had little effect on intracellular cAMP levels in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl osteoblasts. To further confirm COLIV as an activating ligand in osteoblasts, we examined ALP enzyme activity and Ocn mRNA expression, and osteoblast differentiation and mineralization in both Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mouse and control littermate osteoblast cells stimulated with COLIV. Our results showed that COLIV promoted ALP enzyme activity and Ocn mRNA expression (Fig. 5B), and osteoblast differentiation and mineralization (Fig. 5C) in control osteoblast cells. However, COLIV had little effect on Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts.

Fig. 5. COLIV is an activating ligand of Gpr126 to regulate osteoblast differentiation and mineralization.

(A) COLIV stimulated cAMP production in Ctrl osteoblast but not in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts. COLIV (1 μM) was coated on 24-well plates, and then the BMSCs were seeded for differentiation. After 14 days, the cells were harvested and subjected to cAMP ELISA assay. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference. n = 3. (B) COLIV-induced ALP enzyme activity (n = 3) and OCN mRNA expression (n = 2) in Ctrl osteoblasts but not in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. (C) COLIV-stimulated osteoblast differentiation and mineralization in Osx-Cre Ctrl (Ctrl) osteoblasts but not in Gpr126 deletion osteoblasts. ALP staining, von Kossa staining, and Alizarin red staining of BMSCs were performed after 7, 14, and 21 days of differentiation, respectively, while treated with or without COLIV. Scale bars, 5 mm.

Laminin-211 can activate Gpr126 when it is applied under conditions of mechanical force (i.e., vibration); under static conditions, Laminin-211 dose-dependently decreased Schwann cell cAMP levels in a Gpr126-dependent manner (14). Our data showed that, unlike COLIV, Laminin-211 was expressed only in osteoblast cells (fig. S6) and could not activate Gpr126 to regulate osteoblast differentiation and function under static conditions (fig. S7, A to C). Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a key signaling pathway to regulate osteoblast differentiation and function. However, our data showed that the selective Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor KYA1797K has little effect on COLIV-induced osteoblast differentiation and mineralization (fig. S8A). Furthermore, there was no notable difference in Wnt/β-catenin downstream target gene expression when we knocked out Gpr126 in osteoblast cells (fig. S8B). Together, all of our results indicated that COLIV, but not Laminin-211, is an activating ligand of Gpr126 that regulates osteoblast differentiation and maturation by stimulating cAMP signaling, but not Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

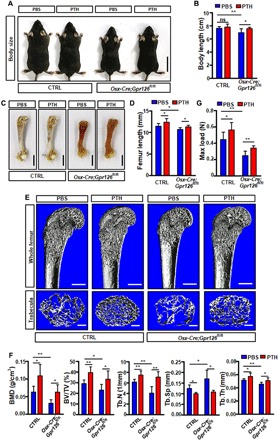

PTH(1–34), but not FSK, rescued the body length and bone mass phenotype induced by osteoblast-specific Gpr126 deletion in vivo

To further confirm whether FSK or PTH(1–34) could rescue the body length or bone mass phenotype induced by Gpr126 deficiency in osteoblasts, we intraperitoneally injected Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and control littermates daily with FSK (200 μg/kg) or PTH (80 μg/kg) from P5 to P30. The results showed that the body length and femur bone length were restored in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice treated with PTH(1–34) (Fig. 6, A to D). Furthermore, three-dimensional reconstruction of the femur using μCT showed that PTH(1–34) rescued trabecular BMD, trabecular bone volume, the number of trabeculae, and trabecular thickness in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (Fig. 6, E and F). As a consequence, the maximum load of the tibia bones was rescued in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice when treated with PTH(1–34) (Fig. 6G). However, the other cAMP activator, FSK, had little effect on the body length, femur bone length, and bone mass in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice (fig. S9, A to G). We speculated that this may be due to effects of FSK on other cell types in vivo, which may counteract the direct effects of FSK on osteoblasts. For instance, interleukin-6 (IL-6), expressed in chondrocytes, was reported to negatively regulate osteoblast differentiation (22) and positively promote osteoclast differentiation and formation (23). Our data showed that Il-6 was strongly expressed in mice chondrocytes (fig. S10A). Furthermore, we found that both mRNA and protein expression of IL-6 in chondrocytes was increased when treated by FSK (fig. S10, B and C). Therefore, our data indicated that PTH, but not FSK, could rescue the body length and bone mass phenotype of Gpr126 loss in the osteoblast lineage not only in vitro but also in vivo.

Fig. 6. The reduction of body length, bone mass, and bone strength in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice was partly rescued by PTH treatment.

Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl (CKO) mice and Ctrl littermates (n = 6 mice per group) were injected daily with PBS or PTH(1–34) (80 μg/kg) from P5 to P30. The mice were then sacrificed for body length, bone length, bone mass, and bone strength analysis. (A and B) Representative images of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl (CKO) mice and Ctrl littermates treated with PBS or PTH(1–34) (80 μg/kg) (A). The body length was measured (B). Scale bars, 2 cm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. n = 6. (C and D) Representative femur bone images of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl (CKO) mice and Ctrl littermates treated with or without PTH(1–34) (80 μg/kg) (C). The femur bone length was measured (D). Scale bars, 2 cm. *P < 0.05. n = 6. (E and F) Bone mass was restored in Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice when treated with PTH. Representative μCT images of femurs from 1-month-old Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice and Ctrl littermates treated with PTH(1–34). The proximal femur (top) and trabecular bone of the femur metaphysis (bottom) are presented (E). Quantitative μCT analysis of femoral trabecular bone parameters (F). Scale bars, 500 μm (E, top) and 200 μm (E, bottom). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. n = 6. (G) Maximal loading of humeral diaphysis from 1-month-old mice by three-point bending assay. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. n = 6. Photo credit: Liang He, East China Normal University.

DISCUSSION

Previous genome-wide association studies have found that variations at the GPR126 locus were strongly associated with shortened human body height (4). However, the mechanism has not been conclusively determined. Here, we have identified that Gpr126 in the osteoblast lineage, but not in osteoclasts and chondrocytes, is a critical regulator of mouse body length and bone mass. Osteoblast lineage–specific Gpr126 deletion resulted in impaired mouse embryonic bone formation and reduced postnatal bone mass by regulating osteoblast differentiation and ossification. The effects of Gpr126 on osteoblast differentiation and bone formation could be mediated primarily through elevation of intracellular cAMP levels to induce phosphorylation of CREB, accompanied by increasing activity and expression of the osteoblast differentiation marker gene ALP as well as Ocn expression. Moreover, we found that COLIV was an activating ligand of Gpr126, resulting in osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. Furthermore, the reduction of body length and bone mass caused by loss of Gpr126 in osteoblasts could be partially restored by PTH treatment in vivo. All our data demonstrated that Gpr126 regulated body height by modulating osteoblast differentiation and ossification.

In our study, we found that the body length shortening phenotype was only observed in the osteoblast lineage conditional Gpr126 deletion mice, but not in osteoclast- or chondrocyte-specific deletion mice. Furthermore, the body length shortening began during embryonic development. The data suggested that Gpr126 regulated body length by affecting osteoblast development. Both osteoblasts and chondrocytes play an important role during embryonic skeletal development, in which most of the bone formation occurs by endochondral ossification (24). Previous research reported that the idiopathic scoliosis and PE induced by cartilage-specific Gpr126 deletion in mice was not through the classical cAMP pathway but by up-regulating the expression of Gal3st4, the gene encoding galactose-3-O-sulfotransferase (8). Our study showed that idiopathic scoliosis and PE did not occur in osteoblast CKO mice. Moreover, Gpr126 regulated bone formation through the classical cAMP-CREB signaling pathway in osteoblast lineage cells. Together, all the results suggest that Gpr126 activates different signaling pathways in specific cell types.

Both COLIV and Laminin-211 have been reported as activating ligands for GPR126 (13, 14). COLIV, a major constituent of the basement membrane, specifically binds to the extracellular N-terminal region of Gpr126 containing the CUB and pentraxin domains and activates Gpr126 signaling, stimulating the production of cAMP in rodent Schwann cells (13). The laminins are a family of large heterotrimeric multidomain proteins that consist of three chains, α, β, and γ, which exist in five, four, and three genetically distinct forms, respectively. There are at least 16 different isoforms of laminin expressed in multiple tissues and organs. Laminins have multiple, often cell type–specific functions (25). Previous studies reported that laminin isoforms are involved in bone regulation. For instance, Laminin-322 negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis in the bone microenvironment (26), whereas Laminin-521 promotes rat BMSC sheet formation (27). Furthermore, laminin subunits, such as LAMB2, play a crucial role in bone development during growth (28), and LAMA1, LAMA2, and LAMA5 can regulate the osteogenic differentiation of dental follicle cells (29). Laminin-211 is a heterotrimeric protein composed of α2, β1, and γ1 chains, encoded by the Lama2, Lamb1, and Lamc1 genes, respectively. It has been reported in zebrafish that Laminin-211 is a previously unidentified ligand for GPR126 to regulate terminal differentiation and myelination by ensuring appropriate levels of cAMP for a given stage of Schwann cell development (14). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that different laminin isoforms or subunits may have varying functions in different cell types. We found that stimulation of osteoblasts with COLIV promoted osteoblast differentiation and function and increased the cAMP level, while it had little effect in Gpr126 KO osteoblasts. However, Laminin-211 had no notable effect on osteoblast differentiation and the intracellular cAMP level in both Gpr126 KO and control osteoblasts. Our results raise the possibility of Gpr126 regulation by different agonists in a cell type–specific manner.

Our results demonstrated that two cAMP agonists, FSK and PTH(1–34), could rescue the reduction of osteoblast differentiation and mineralization induced by Gpr126 deletion in vitro. However, only PTH(1–34), but not FSK, rescued the body length and bone mass phenotype of osteoblast-specific Gpr126 deletion mice in vivo. This difference could be explained by an effect of FSK on the microenvironment. The dietary supplement FSK, which is widely used for weight loss (30) and cardiovascular diseases (31), stimulates Il-6 expression in chondrocytes (32), and IL-6 was reported to negatively regulate osteoblast differentiation (22) and positively promote osteoclast differentiation and formation (23). Furthermore, it has been previously reported that Il-6 overexpression leads to body length shortening and bone mass decrease by reducing osteoblast differentiation and increasing osteoclast number and activity in vivo (33). Our data showed that both mRNA and protein expression of IL-6 in chondrocytes was increased in a dose-dependent manner with FSK stimulation, which confirmed our hypothesis. A similar mechanism could function through regulation of glucocorticoids. FSK stimulates glucocorticoid production in the adrenal cortex by increasing cAMP (34), and glucocorticoids could negatively regulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (35). A bone mass decrease was found in children after long-term glucocorticoid treatment (36). Therefore, FSK may have had only limited effects on the body length and bone mass phenotype in Gpr126 deletion mice due to microenvironmental factors including IL-6 expression induced by FSK, offsetting the positive effect of FSK on osteoblasts in vivo. PTH(1–34) is a clinically used osteoporosis drug that functions by stimulating osteoblast proliferation (37), increasing osteoblast activity (38), and protecting osteoblasts from apoptosis (39) by directly binding to its receptor PTH1R (40). All our results suggested that it could be used to counteract the shortened human height caused by GPR126 mutation.

In summary, this study suggests that loss of Gpr126 in osteoblasts could delay osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, resulting in shortened body length and bone mass decrease in mice. Gpr126 signals through the cAMP-CREB signaling pathway in osteoblasts, with COLIV as a ligand activating Gpr126 to positively regulate osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Last, PTH(1–34) may be worth studying as a potential drug to treat the shortened human height or loss of bone mass caused by Gpr126 mutation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Methods

Mouse generation and maintenance

All experiments using mice were approved by the East China Normal University (ECNU) Animal Care and Use Committee. Gpr126fl/fl (strain C57/BL/6) was purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms. Osx-Cre, Col2-Cre, and Lysm-Cre mice (strain C57/BL/6) were purchased from the Center for Animal Research of ECNU. We used homologous recombination to develop a mouse model in which exon 2 of Gpr126 was flanked by loxP sites (Gpr126fl/fl; fig. S1). The generation of Gpr126fl/fl mice is described in fig. S1. Osx-Cre, Lysm-Cre, and Col2-Cre mice were mated with Gpr126fl/fl mice to generate Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl, Lysm-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl, and Col2-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice, respectively. For genotyping these specific KO mice, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer sequences are 5′-TTTCCCGCAGAACCTGAAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGTGCTAACCAGCGTTTTCGT-3′ (reverse) for Osx-Cre, 5′-AATCCATATTGGCAGAACGAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGACCAGAGTCATCCTTAGCG-3′ (reverse) for Col2-Cre, and 5′-CCCAGAAATGCCAGATTACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTGGGCTGCCAGAATTTCTC-3′ (reverse) for Lysm-Cre. Both male and female mice were used in all experiments, and all the mice were randomly assigned to groups. All experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Ethics Committee at ECNU.

Cell culture

For osteoblast differentiation analyses in vitro, we isolated BMSCs from 4-week-old mice femur and tibia bones. The growth culture medium was α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM; HyClone, SH30265.01) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, 10099-1633101) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (HyClone, SH40003-12). The differentiation culture medium was α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, l-ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml; Sigma, A4034), 0.1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; D4902), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, G6376), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (HyClone, SH40003-12), and the medium was refreshed every 2 days. BMSCs were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates, and cell cultures were incubated in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. For chondrocyte differentiation analyses in vitro, the BMSCs were isolated from 4-week-old mice, then seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates cultured with transforming growth factor–β3 (TGF-β3) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 14 days, and then stained by Alcian blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For quantification, stained Alcian blue was eluted with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride for 8 hours. The optical absorbance was measured at 620 nm using a microplate reader. For osteoclast differentiation analyses, the bone marrow cells were isolated from 8-week-old mice. After 6 days of culture in M-CSF (macrophage colony-stimulating factor) (30 ng/ml) and RANKL (30 ng/ml; R&D Systems), the cells in the 96-well plate were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde for 15 min and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining.

ALP, Alizalin red S, and von Kossa staining

We plated BMSCs at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates and expanded them in growth medium for 3 days. We induced osteoblast differentiation by culturing in differentiation culture medium. At days 7, 14, and 21 after inducing osteoblast differentiation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min and then stained with ALP detection solution (Sigma, N5000; F3381), 2.5% silver nitrate solution (Energy Chemical, 7761-88-8), or 1% Alizarin red S (Sigma, A5533-25G) for ALP, Alizalin red S, and von Kossa staining, respectively, using standard protocols.

ALP assay

After removing the medium, 24-well plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then 0.1% Triton X-100 buffer was added. Cells were frozen and thawed three times, and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min in substrate buffer (Sigma, N7653-100ML). The reaction was then terminated with 3 N NaOH. The optical density of the solution was determined at 405 nm. The ALP activity in each well was divided by the total protein in each well.

CFU-F and CFU-Ob assays

Bone marrow cells harvested from femoral and tibial cavities of 4-week-old mice were cleared of red blood cells and plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in six-well plates. After 24 hours of adhesion, we removed unattached cells and changed the culture medium every 2 days. Colonies were cultured for 14 days in growth culture medium (for CFU-F) or differentiation culture medium (for CFU-Ob), then medium was removed, and each well was washed with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (for CFU-F) or ALP (for CFU-Ob). Colonies that contained 50 or more cells were counted.

Western blot analysis

The BMSCs were cultured 14 days in differentiation culture medium, harvested, and lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche) on ice. The insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatants were collected and frozen at −80°C. Total protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Thermo Scientific). Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were separated on a 9% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred to 0.22-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Whatman). The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and incubated with primary antibodies directed against CREB [Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA; 9197], p-CREB (CST 9198), OCN (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab93876), or β-actin (CST, 3700) overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibodies (LI-COR, 926-32211/926-32210). The protein bands were visualized with Immun-Star WesternC (LI-COR, USA).

Real-time PCR

BMSCs were isolated from 4-week-old mice, and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Takara, 9109) from cells cultured for 0, 7, or 14 days in differentiation culture medium. The RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme, R222-01), and real-time PCR analysis was performed using a real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Singapore) with Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Low Rox Plus) (YEASEN, 11202ES03). We used predesigned real-time PCR assays from Applied Biosystems for the analysis of ALP and OCN. The PCR primer sequences used were 5′-GTACGCCAACACAGTGCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTG-3′ (reverse) for β-actin, 5′-TCCTGACCAAAAACCTCAAAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCTTCATGCAGAGCCTGC-3′ (reverse) for ALP, 5′-CTCACAGATGCCAAGCCCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAAGGTAGCGCCGGAGTCT-3′ (reverse) for OCN, 5′-CCAAAGTTGGCAATGAAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTGGATCAGGTAGGAACCA-3′ (reverse) for Gpr126, 5′-CAAATCGGACCCACTGGTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTCCTGGATGGCCGATGTT-3′ (reverse) for COLIV, 5′-TGAGTATGAAAGCAAGGCCAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAAAACCAGGCTTGGGGAA-3′ (reverse) for Laminin-211, and 5′-CAAAGCCAGAGTCCTTCAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTCTG-3′ (reverse) for Il-6.

Skeletal preparations

Embryos were eviscerated and placed in water at 4°C overnight. Bodies were immersed in a 67°C water bath for 1 min, skinned, and fixed in ethanol for 3 days. Alcian blue 8GX (150 mg; Sigma, A5268-10G) was added to a mixture of 80 ml of 95% ethanol and 20 ml of glacial acetic acid. Cartilage was stained for 8 to 12 hours, rinsed in 100% ethanol overnight, and cleared in 2% KOH for 6 hours. Alizarin red S (50 mg; Sigma) was added to 1 liter of 2% KOH, and the embryos were immersed for 3 hours to counterstain bone. Skeletons were cleared in 2% KOH and 20% glycerol and stored in 50% ethanol and 50% glycerol.

μCT analysis

Femurs from Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and Ctrl littermate mice were scanned using x-ray microtomography (SKYSCAN 1272, Bruker microCT). The samples were scanned at a tube potential of 60.0 kV and 166.0 μA for 15 min and a resolution of 7-μm pixels. The region of interest was located from 7.280 mm (1040 image slices) to 7.980 mm (1140 image slices). Trabecular bone parameters of the femur were calculated using CTan software (Bruker microCT). Three-dimensional reconstruction images were produced with CTVOL (Bruker microCT). The bone range was reflected with CT analyzer manual, which ranged from more than 1000 CT number, and the CT numbers of air (1000 HU) and water (0 HU) were used to calibrate the image values in Hounsfield units. The mean value was determined by the CT number. The femur sample area selected for scanning was 0.7 mm below the growth plate.

Three-point bending test

To measure the bone strength of the humerus, the small animal bone strength test instrument (YLS-16A, Corp., Yanyi Jinan, P.R. China) was used to perform the three-point bending test. Immediately after dissection, the fresh humerus was examined using the three-point bending test. Two end support points and one central loading point were used for the three-point bending test. The biomechanical measurement data were collected from the load-deformation curves. The maximum load (N) was recorded.

Histology and in situ hybridization

Histomorphometry was performed on plastic-embedded tissues using standard protocols. Calcein double labeling was performed by injecting mice with calcein (30 mg/kg) on P30 and P40. Mice were sacrificed on P47, and bones were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in methyl methacrylate. Bone dynamic histomorphometric analyses for BFR/BS (bone formation rate per bone surface) and MAR (mineral apposition rate) as well as bone static histomorphometric analyses for Ob.S/BS (osteoblast surface per bone surface), OS/BS (osteoid per bone surface), and O.Th (osteoid thickness) were made using the OsteoMeasure Histomorphometry System (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, GA, USA). The bone histomorphometric parameters were calculated and expressed according to the standardized nomenclature for bone histomorphometry. Digoxigenin (DIG)–labeled antisense and sense probes were produced using the DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s directions. To examine osteoclast parameters in vivo, the femurs from 8-week-old mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and decalcified in 9% EDTA (pH 7.4) for 7 days before embedding in paraffin and then staining for TRAP. Osteoclast surface/bone surface (Oc.S/BS), the number of osteoclasts/bone perimeter (N.Oc/B.Pm), and the eroded surface/bone surface (ES/BS) were analyzed with the OsteoMeasure Analysis System (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, GA, USA).

Immunofluorescence

The femur tissue sections from E18.5 mice were incubated with Anti-Collagen X antibody (Abcam, ab58632) overnight followed by secondary antibodies (Sigma, T8072) for 90 min. Images were captured on a microscope (Olympus, BX53F).

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± SD for absolute values, as indicated in the vertical axis legend of the figures. The statistical significance of differential findings between CKO and Ctrl mice was calculated by SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the effects of treatment with FSK, PTH, COLIV, and Laminin-211. Significance was P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1105102 to J.L., 2018YFA0507001 to M.L., and 2018YFC2001500 to J.S.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81811530339, 81722020, and 91949127 to J.L.; 81830083 to M.L.; and 91749204 to J.S.), the Innovation Program of the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2017-01-07-00-05-E00011 to M.L.), and Shenzhen Municipal Government of China (KQTD20170810160226082 to M.L.). Author contributions: Study design: P.S., L.H., M.L., and J.L.; study conduct: P.S., L.H., K.J., Z.Y., Z.L., and F.X.; interpreted results: S.S., S.L., and Y.J.; bioinformatic analysis: S.L.; drafting manuscript: P.S., L.H., M.L., and J.L.; revising manuscript content: S.S., P.S., L.H., and J.L.; supervised the study: J.S., M.L., and J.L. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/12/eaaz0368/DC1

Fig. S1. Strategy of targeting the Gpr126flox allele.

Fig. S2. The expression of Gpr126 in different bone cells and genotyping.

Fig. S3. Body length and embryonic bone formation in Lysm-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and Col2-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl was not different compared to their control littermates.

Fig. S4. Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblast lineage (Osx-Cre) had little effect on osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast activity in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. S5. Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblast lineage (Osx-Cre) had little effect on chondrocyte differentiation and hypertrophy.

Fig. S6. The expression of COLIV and Laminin-211 in osteoblast, osteoclast, and chondrocyte cells.

Fig. S7. Laminin-211 was not an activating ligand of Gpr126 to regulate osteoblast differentiation and mineralization under static conditions.

Fig. S8. The selective Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor KYA1797K had little effect on COLIV-induced osteoblast differentiation and mineralization.

Fig. S9. Administration of FSK had little effect on the body length, femur bone length, bone mass, and bone strength of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice.

Fig. S10. The expression of IL-6 was increased in chondrocytes treated by FSK.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Luo J., Sun P., Siwko S., Liu M., Xiao J., The role of GPCRs in bone diseases and dysfunctions. Bone Res. 7, 19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassilana F., Nash M., Ludwig M.-G., Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors: Opportunities for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 869–884 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langenhan T., Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors—Candidate metabotropic mechanosensors and novel drug targets. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 11, 1–12 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Valk R. J. P., Kreiner-Møller E., Kooijman M. N., Guxens M., Stergiakouli E., Sääf A., Bradfield J. P., Geller F., Hayes M. G., Cousminer D. L., Körner A., Thiering E., Curtin J. A., Myhre R., Huikari V., Joro R., Kerkhof M., Warrington N. M., Pitkänen N., Ntalla I., Horikoshi M., Veijola R., Freathy R. M., Teo Y.-Y., Barton S. J., Evans D. M., Kemp J. P., Pourcain B. S., Ring S. M., Smith G. D., Bergström A., Kull I., Hakonarson H., Mentch F. D., Bisgaard H., Chawes B., Stokholm J., Waage J., Eriksen P., Sevelsted A., Melbye M.; Early Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE) Consortium, van Duijn C. M., Medina-Gomez C., Hofman A., de Jongste J. C., Taal H. R., Uitterlinden A. G.; Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium, Armstrong L. L., Eriksson J., Palotie A., Bustamante M., Estivill X., Gonzalez J. R., Llop S., Kiess W., Mahajan A., Flexeder C., Tiesler C. M. T., Murray C. S., Simpson A., Magnus P., Sengpiel V., Hartikainen A.-L., Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S., Lewin A., Da Silva Couto Alves A., Blakemore A. I., Buxton J. L., Kaakinen M., Rodriguez A., Sebert S., Vaarasmaki M., Lakka T., Lindi V., Gehring U., Postma D. S., Ang W., Newnham J. P., Lyytikäinen L.-P., Pahkala K., Raitakari O. T., Panoutsopoulou K., Zeggini E., Boomsma D. I., Groen-Blokhuis M., Ilonen J., Franke L., Hirschhorn J. N., Pers T. H., Liang L., Huang J., Hocher B., Knip M., Saw S.-M., Holloway J. W., Melén E., Grant S. F. A., Feenstra B., Lowe W. L., Widén E., Sergeyev E., Grallert H., Custovic A., Jacobsson B., Jarvelin M.-R., Atalay M., Koppelman G. H., Pennell C. E., Niinikoski H., Dedoussis G. V., Mccarthy M. I., Frayling T. M., Sunyer J., Timpson N. J., Rivadeneira F., Bønnelykke K., Jaddoe V. W. V.; Early Growth Genetics (EGG) Consortium , A novel common variant in DCST2 is associated with length in early life and height in adulthood. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 1155–1168 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin X., Xu L., Xia C., Zhu W., Sun W., Liu Z., Qiu Y., Zhu Z., Genetic variant of GPR126 gene is functionally associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in chinese population. Spine 42, E1098–E1103 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravenscroft G., Nolent F., Rajagopalan S., Meireles A. M., Paavola K. J., Gaillard D., Alanio E., Buckland M., Arbuckle S., Krivanek M., Maluenda J., Pannell S., Gooding R., Ong R. W., Allcock R. J., Carvalho E. D. F., Carvalho M. D. F., Kok F., Talbot W. S., Melki J., Laing N. G., Mutations of GPR126 are responsible for severe arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 955–961 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitagaki J., Miyauchi S., Asano Y., Imai A., Kawai S., Michikami I., Yamashita M., Yamada S., Kitamura M., Murakami S., A putative association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in GPR126 with aggressive periodontitis in a Japanese population. PLOS ONE 11, e0160765 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karner C. M., Long F., Solnica-Krezel L., Monk K. R., Gray R. S., Gpr126/Adgrg6 deletion in cartilage models idiopathic scoliosis and pectus excavatum in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 4365–4373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez C., Iyer M., Low I., Gpr126 is critical for Schwann cell function during peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Neurosci. 37, 3106–3108 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patra C., van Amerongen M. J., Ghosh S., Ricciardi F., Sajjad A., Novoyatleva T., Mogha A., Monk K. R., Mühlfeld C., Engel F. B., Organ-specific function of adhesion G protein-coupled receptor GPR126 is domain-dependent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 16898–16903 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geng F.-S., Abbas L., Baxendale S., Holdsworth C. J., Swanson A. G., Slanchev K., Hammerschmidt M., Topczewski J., Whitfield T. T., Semicircular canal morphogenesis in the zebrafish inner ear requires the function of gpr126 (lauscher), an adhesion class G protein-coupled receptor gene. Development 140, 4362–4374 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamann J., Aust G., Araç D., Engel F. B., Formstone C., Fredriksson R., Hall R. A., Harty B. L., Kirchhoff C., Knapp B., Krishnan A., Liebscher I., Lin H.-H., Martinelli D. C., Monk K. R., Peeters M. C., Piao X., Prömel S., Schöneberg T., Schwartz T. W., Singer K., Stacey M., Ushkaryov Y. A., Vallon M., Wolfrum U., Wright M. W., Xu L., Langenhan T., Schiöth H. B., International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCIV. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 67, 338–367 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paavola K. J., Sidik H., Zuchero J. B., Eckart M., Talbot W. S., Type IV collagen is an activating ligand for the adhesion G protein-coupled receptor GPR126. Sci. Signal. 7, ra76 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen S. C., Luo R., Liebscher I., Giera S., Jeong S.-j., Mogha A., Ghidinelli M., Feltri M. L., Schöneberg T., Piao X., Monk K. R., The adhesion GPCR GPR126 has distinct, domain-dependent functions in Schwann cell development mediated by interaction with Laminin-211. Neuron 85, 755–769 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Küffer A., Lakkaraju A. K. K., Mogha A., Petersen S. C., Airich K., Doucerain C., Marpakwar R., Bakirci P., Senatore A., Monnard A., Schiavi C., Nuvolone M., Grosshans B., Hornemann S., Bassilana F., Monk K. R., Aguzzi A., The prion protein is an agonistic ligand of the G protein-coupled receptor Adgrg6. Nature 536, 464–468 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebscher I., Schön J., Petersen S. C., Fischer L., Auerbach N., Demberg L. M., Mogha A., Cöster M., Simon K.-U., Rothemund S., Monk K. R., Schöneberg T., A tethered agonist within the ectodomain activates the adhesion G protein-coupled receptors GPR126 and GPR133. Cell Rep. 9, 2018–2026 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glenn T. D., Talbot W. S., Analysis of Gpr126 function defines distinct mechanisms controlling the initiation and maturation of myelin. Development 140, 3167–3175 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui H., Wang Y., Huang H., Yu W., Bai M., Zhang L., Bryan B. A., Wang Y., Luo J., Li D., Ma Y., Liu M., GPR126 protein regulates developmental and pathological angiogenesis through modulation of VEGFR2 receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34871–34885 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mogha A., Benesh A. E., Patra C., Engel F. B., Schöneberg T., Liebscher I., Monk K. R., Gpr126 functions in Schwann cells to control differentiation and myelination via G-protein activation. J. Neurosci. 33, 17976–17985 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J.-M., Choi J. S., Kim Y.-H., Jin S. H., Lim S., Jang H.-J., Kim K.-T., Ryu S. H., Suh P.-G., An activator of the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway promotes osteogenesis from human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 228, 617–626 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen B., Lin T., Yang X., Li Y., Xie D., Cui H., Intermittent parathyroid hormone (1-34) application regulates cAMP-response element binding protein activity to promote the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stromal cells, via the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 11, 2399–2406 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneshiro S., Ebina K., Shi K., Higuchi C., Hirao M., Okamoto M., Koizumi K., Morimoto T., Yoshikawa H., Hashimoto J., IL-6 negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation through the SHP2/MEK2 and SHP2/Akt2 pathways in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 32, 378–392 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Q., Zhou X. K., Huang D. Q., Ji Y. C., Kang F. W., IL-6 enhances osteocyte-mediated osteoclastogenesis by promoting JAK2 and RANKL activity in vitro. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 41, 1360–1369 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao J., Li X., Zhang Y., Wang H., Endochondral ossification in hindlimbs during Bufo gargarizans metamorphosis: A model of studying skeletal development in vertebrates. Dev. Dynam. 247, 1121–1134 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L., Zhang J., Akimenko M.-A., Inhibition of mmp13a during zebrafish fin regeneration disrupts fin growth, osteoblasts differentiation, and Laminin organization. Dev. Dynam. 249, 187–198 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uehara N., Kukita A., Kyumoto-Nakamura Y., Yamaza T., Yasuda H., Kukita T., Osteoblast-derived Laminin-332 is a novel negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis in bone microenvironments. Lab. Invest. 97, 1235–1244 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Z., Xi Y., Lai K., Wang Y., Wang H., Yang G., Laminin-521 promotes rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell sheet formation on light-induced cell sheet technology. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 9474573 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beaufils C., Farlay D., Machuca-Gayet I., Fassier A., Zenker M., Freychet C., Bonnelye E., Bertholet-Thomas A., Ranchin B., Bacchetta J., Skeletal impairment in Pierson syndrome: Is there a role for lamininβ2 in bone physiology? Bone 106, 187–193 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viale-Bouroncle S., Gosau M., Morsczeck C., Laminin regulates the osteogenic differentiation of dental follicle cells via integrin-α2/-β1 and the activation of the FAK/ERK signaling pathway. Cell Tissue Res. 357, 345–354 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ríos-Hoyo A., Gutiérrez-Salmeán G., New dietary supplements for obesity: What we currently know. Curr. Obes. Rep. 5, 262–270 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.García-Morales V., Luaces-Regueira M., Campos-Toimil M., The cAMP effectors PKA and Epac activate endothelial NO synthase through PI3K/Akt pathway in human endothelial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 145, 94–101 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang P., Zhu F., Konstantopoulos K., Prostaglandin E2 induces interleukin-6 expression in human chondrocytes via cAMP/protein kinase A- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent NF-κB activation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C1445–C1456 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Benedetti F., Rucci N., Fattore A. D., Peruzzi B., Paro R., Longo M., Vivarelli M., Muratori F., Berni S., Ballanti P., Ferrari S., Teti A., Impaired skeletal development in interleukin-6-transgenic mice: A model for the impact of chronic inflammation on the growing skeletal system. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 3551–3563 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans A. N., Liu Y., MacGregor R., Huang V., Aguilera G., Regulation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone transcription by elevated glucocorticoids. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 1796–1807 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komori T., Glucocorticoid signaling and bone biology. Horm. Metab. Res. 48, 755–763 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park H. W., Tse S., Yang W., Kelly H. W., Kaste S. C., Pui C.-H., Relling M. V., Tantisira K. G., A genetic factor associated with low final bone mineral density in children after a long-term glucocorticoids treatment. Pharmacogenomics J. 17, 180–185 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang K., Wang M., Li Y., Li C., Tang S., Qu X., Feng N., Wu Y., The PERK-EIF2α-ATF4 signaling branch regulates osteoblast differentiation and proliferation by PTH. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 316, E590–E604 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwata A., Kanayama M., Oha F., Hashimoto T., Iwasaki N., Effect of teriparatide (rh-PTH 1-34) versus bisphosphonate on the healing of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: A retrospective comparative study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 18, 148 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu R., Wang Q., Han Y., Li J., Yang X.-J., Miao D., Parathyroid hormone administration improves bone marrow microenvironment and partially rescues haematopoietic defects in Bmi1-null mice. PLOS ONE 9, e93864 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balani D. H., Ono N., Kronenberg H. M., Parathyroid hormone regulates fates of murine osteoblast precursors in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 3327–3338 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/12/eaaz0368/DC1

Fig. S1. Strategy of targeting the Gpr126flox allele.

Fig. S2. The expression of Gpr126 in different bone cells and genotyping.

Fig. S3. Body length and embryonic bone formation in Lysm-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl and Col2-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl was not different compared to their control littermates.

Fig. S4. Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblast lineage (Osx-Cre) had little effect on osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast activity in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. S5. Deletion of Gpr126 in osteoblast lineage (Osx-Cre) had little effect on chondrocyte differentiation and hypertrophy.

Fig. S6. The expression of COLIV and Laminin-211 in osteoblast, osteoclast, and chondrocyte cells.

Fig. S7. Laminin-211 was not an activating ligand of Gpr126 to regulate osteoblast differentiation and mineralization under static conditions.

Fig. S8. The selective Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor KYA1797K had little effect on COLIV-induced osteoblast differentiation and mineralization.

Fig. S9. Administration of FSK had little effect on the body length, femur bone length, bone mass, and bone strength of Osx-Cre;Gpr126fl/fl mice.

Fig. S10. The expression of IL-6 was increased in chondrocytes treated by FSK.