Abstract

It is increasingly popular for titanium and its alloys to be utilized as the medical implants. However, their bio-inert nature and lack of antibacterial ability limit their applications. In this work, by utilizing plasma immersion ion implantation and deposition (PIII&D) technology, the titanium surface was modified by C/Cu co-implantation. The mechanical property, corrosion resistance, antibacterial ability and cytocompatibility of modified samples were studied. Results indicate that after C/Cu co-implantation, copper nanoparticles were observed on the surface of titanium, and titanium carbide existed on the near surface region of titanium. The modified surface displayed good mechanical property and corrosion resistance. The Cu/C galvanic corrosion existed on the titanium surface implanted by C/Cu dual ions, and release of copper ions can be effectively controlled by the galvanic corrosion effect. Moreover, improved antibacterial performance of titanium surface can be achieved without cytotoxicity.

Keywords: Titanium, Ion implantation, Carbon, Copper, Antibacterial ability

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

C/Cu dual ions were co-implanted into titanium.

-

•

C/Cu-Ti displayed improved mechanical property and corrosion resistance compared to Ti and single ion implanted titanium.

-

•

C/Cu-Ti exhibit better biocompatibility and higher antibacterial activity compared to Ti and single ion implanted titanium.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the number of patients with osteoarthrosis and the demand for artificial joints are growing because of faster aging population [1,2]. It is more popular for titanium and its alloys used as artificial joint materials [[3], [4], [5]]. However, the biological activity of the titanium materials is not ideal to combine with the surrounding tissue in a short time [6,7]. In addition, an oxide passivation film is usually formed on the titanium surface, which may be peeled off and dissolved under the influence of external force and body fluid [8,9]. This may cause toxicity, inflammation, and thrombosis in the body, so the corrosion resistance of titanium needs to be improved. Furthermore, titanium surface lacks antibacterial ability, which may cause postoperative bacterial infection, eventually leading to surgical failure [10]. Thus, it is important to modify titanium surface to improve its biological activity, mechanical property, corrosion resistance and antibacterial ability.

A diamond-like carbon film is an amorphous carbon film with performances similar to those of a diamond film. Owing to good corrosion resistance, wear resistance and biocompatibility, DLC film has been obtained great attention in the field of biomedicine, especially artificial joints for more than 10 years [[11], [12], [13]]. There are various ways to prepare DLC films, including CVD (chemical vapor deposition) [14], PVD (physical vapor deposition) [15], and PIII&D (plasma immersion ion implantation and deposition) [16,17]. Compared to CVD and PVD, PIII&D technology has some unique features. It has the advantages of full-scale implantation, surface reaction, high reactivity of the injected component, and no distinct interface exists between the substrate and the modified layer [18,19]. By using this technology and controlling process parameters, carbon ions can be implanted into titanium and its alloys to form TiC or DLC modified layer on their surfaces to improve mechanical property and corrosion resistance [[20], [21], [22]].

However, the surface of the C-implanted titanium in our previous research cannot inhibit bacterial growth well enough [23]. Amorphous carbon can only interact with those bacteria adhered on its surface, so the interaction between amorphous carbon and bacteria is weak [26,27]. Copper (Cu) is an essential micronutrient which has received increasing attention because of its role in wound healing, angiogenesis and antibacterial activities [24,25]. Cu ions released tend to interact in a wide range with cells or bacteria. Thus, co-implantation of C and Cu into titanium, may produce better antibacterial ability than single Cu implantation, which combined both antibacterial effects of carbon and copper ions.

In this work, titanium surface is modified by C/Cu dual ions implantation using PIII&D technology. Mechanical property, corrosion resistance, antibacterial ability and cytotoxicity of implanted samples are investigated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. C/Cu ions implantation

Commercial pure titanium plates were cut into samples with the sizes of 10 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm and 20 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm , and then those samples were pretreated with mixed acid (HF and HNO3), before being ultra-sonicated with alcohol and ultrapure water in sequence. The samples were placed in a target table of PIII&D vacuum chamber, Carbon target was high-purity graphite rod (99.99%, 10 × 28 mm), and copper target was high-purity copper rod (99.99%, 10 × 28 mm). Vacuum was pulled below 5 × 10−3 Pa, and then carbon and copper implantation or carbon/copper dual ions implantation were conducted for 1 h, and parameters of implantation are displayed in Table 1. Samples with carbon implantation were represented by C–Ti; samples with copper implantation were represented by Cu–Ti, and samples with carbon/copper ions co-implantation were represented by C/Cu–Ti.

Table 1.

Parameters used for C/Cu plasma immersion ions implantation & deposition (PIII&D).

| C–Ti | Cu–Ti | C/Cu–Ti | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implantation voltage (kV) | −30 | −30 | −30 |

| Implantation pulse duration (μs) | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Pulsing frequency (Hz) | 8 | 8 | 8 |

2.2. Surface characterization

A field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; S-4800, Hitachi, Japan) was harnessed to observe surface morphologies of samples. The surface element composition of samples was probed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Physical electronics PHI-5802, PHI, USA), and XPS high-resolution spectrum was used to analyze the chemical states of elements.

2.3. Wettability of surfaces

A contact angle meter (SL200B, Solon, China) was utilized to analyze the wettability of surfaces. 2 μL of ultrapure water was dropped vertically on samples’ surfaces. Then, the contact angle of the droplet was measured.

2.4. Surface zeta potential

A surpass electric analyzer was utilized to detect the zeta potential (ζ) of surface. Two samples with the size of 20 × 10 × 1 mm3 were placed on the stage, and the distance of gap between two parallel samples was adjusted to 100 ± 5 μm to ensure that the electrolyte (0.001 mol/L KCl solution) passed through the gap. HCl and NaOH solutions were added to change pH value of the electrolyte in the range of 5.0–9.0. The current and pressure on the sample’ surface were measured at a certain pH value, and Helmholtz-Smoluchowski formula was adopted to calculate the value of zeta potential (ζ) [28]:

| (1) |

where A and L are the cross-sectional area and length of the electrolyte channel, respectively; η, ε, ε0 are the viscosity of the electrolyte, the dielectric constant and the vacuum dielectric constant respectively; dI/dP is the slope of the flow current versus pressure change.

2.5. Cu2+ release

C/Cu–Ti and Cu–Ti were placed in centrifuge tubes with 10 mL of PBS and these tubes were placed in a 37 °C incubator. An inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) was used to determine the amounts of released copper ions (1, 4, 7, and 14 days).

2.6. Test of electrochemical performance

A CHI760C electrochemical workstation was used to test the corrosion resistance of different samples. The working electrode was a test sample, and a graphite electrode acted as the counter electrode, while a saturated calomel electrode serveed as the reference electrode. The electrolyte used in this test was 0.9 wt% NaCl solution, and the Tafel curve of each sample was measured at room temperature, and the scanning rate was set to 0.01 V/s.

2.7. Hardness of surface

A G200 nano-indenter was harnessed to measure the micro-hardness value of the test sample's surface, meanwhile the hardness was measured by selecting 3 points on each sample.

2.8. Test of antibacterial ability

By using S. aureus (ATCC 25923) and E. coli (ATCC 25922), the antibacterial ability of samples modified through ion implantation was evaluated. After sterilized under light of ultraviolet for 24 h, samples were put into a 24-well plate, and 100 μL of bacterial liquid with a bacterial concentration of 106 cfu/mL was added to each sample's surface. Bacteria on various surfaces were then cultured in a 37 °C incubator for 24 h, before being quickly transferred to centrifuge tubes containing 4 mL of physiological saline, and these tubes were shaken vigorously on a shaker for 30 s to detach the bacteria from the sample. Afterwards, the isolated bacterial suspensions were sequentially diluted 10 times in the sterilized physiological saline, and then 100 μL of the diluted bacterial solutions were uniformly applied to standard agar plates (Nutrient Broth No. 2 (NB) for S. aureus and Luria-Bertani (LB) for E. coli). After cultured for 16 h in a 37 °C incubator, the agar plates were removed from the incubator to count the number of colonies, and the antibacterial rate of the sample was calculated by using the following formula:

| (2) |

K: sample antibacterial rate.

A: Number of colonies in the control sample.

B: Number of colonies in the experimental group.

Besides, an additional sample was added to each culture group to observe the microscopic morphology and number of bacteria under a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

2.9. Cytotoxicity evaluation

Cytotoxicity of each sample was evaluated by using mouse osteoblast cells (MC3T3-E1). The MC3T3-E1 cells with a density of 2 × 104 cells/mL were seeded on the surfaces of samples, and every 3 days the culture solution was changed. After 1, 4, and 7 days, an original culture medium was aspirated, and a fresh culture medium which contained 10% alamarBlue™ was added. At the end of incubation, 100 μL of the medium was pipetted from each well into a black 96-well plate (Nunc, USA). And the intensity of fluorescence was measured in a condition where the wavelengths of excitation and emission were 550 nm and 590 nm, respectively.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Experimental data were statistically analyzed by means of GraphPad Prism software. Differences between experimental variables in different groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multi-group comparison experiments. Each set of variables contained at least three valid values, and the significance difference level was set to p = 0.05. If p < 0.05, a statistically significant difference existed.

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Surface characterization

Fig. 1 shows surface morphologies of samples before and after ions implantation. There was gully-shaped structure formed by mixed acid processing, and the surface morphologies of samples did not have obvious change after ion implantation (Fig. 1a–d). However, through observation from high-magnification images (Fig. 1e–h), both Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti surfaces contained nano-particles, which were formed due to process of Cu-PIII&D [29,30].

Fig. 1.

Morphology of surfaces at low magnification (a-d) and high magnification (e-f).

Atomic percentages of elements in 30 nm depth of samples analyzed though XPS are shown in Table 2. According to this table, carbon and copper ions have been successfully implanted into the modified substrates. Exactly, carbon relative atomic percentages of C–Ti and C/Cu–Ti were about 13.78 at.% and 10.04 at.%, respectively, while the copper relative atomic percentages of Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti were about 11.84 at.% and 13.68 at.%, respectively.

Table 2.

XPS atomic percentages of elements at 30 nm depth of samples.

| Element (at.%) | C–Ti | Cu–Ti | C/Cu–Ti |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1s | 13.78 | – | 10.04 |

| Cu2p | – | 11.84 | 13.68 |

| O1s | 40.35 | 53.88 | 44.12 |

| Ti2p | 45.87 | 34.28 | 32.17 |

C 1s high-resolution XPS on surfaces and at 30 nm depth of C–Ti and C/Cu–Ti are displayed in Fig. 2a–d. As shown from Fig. 2a, there were four fitting peaks in C 1s high-resolution spectrum on surface of the C–Ti, main peak at 284.30 eV corresponded to C 1s binding energy in amorphous carbon [31], and double peaks at 285.70 eV and 281.50 eV corresponded to C 1s binding energy in graphite [32] and titanium carbide, [33] respectively. The peak at 288.00 eV corresponded to C=O chemical bond [34]. Fig. 2c shows C 1s high-resolution spectrum at 30 nm depth of C–Ti sample, and single peak at 281.50 eV corresponded to C 1s binding energy in titanium carbide [33]. C 1s peak on surface of the C/Cu–Ti sample (Fig. 2b) was located at 284.31 eV and 288.00 eV corresponding to C 1s binding energy in amorphous carbon and C=O chemical bond. C 1s high-resolution spectrum (Fig. 2d) of C/Cu-Ti at 30 nm depth was located at 281.50 eV, corresponding to C 1s binding energy in titanium carbide [33]. These results indicate carbon elements existed in C/Cu–Ti and C–Ti as titanium carbide and existed on the surfaces of these two samples in the form of amorphous carbon. XPS high-resolution spectra of Cu 2p from surfaces and inside of Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti at 30 nm depth are exhibited in Fig. 2e–h. There were six fitting peaks in Cu–Ti surface's Cu 2p high-resolution spectrum in Fig. 2e, where double peaks at 952.45 eV and 932.00 eV corresponded to Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 binding energies in metallic Cu, respectively [35,36], double peaks at 954.00 eV and 934.20 eV corresponded to Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 binding energies in copper oxide, respectively [37]. In addition, characteristic peaks occurred at 962.00 and 941.90 eV corresponded to satellite peaks of CuO [[38], [39]].

Fig. 2.

C1s XPS high-resolution spectra gained from C–Ti and C/Cu–Ti surfaces (a and b) and inside at 30 nm depth (c and d); Cu 2p XPS high-resolution spectra gained from Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti surfaces (e and f) and inside at 30 nm depth (g and h).

XPS high-resolution spectrum of Cu 2p gained from the inside of Cu–Ti at 30 nm depth is shown in Fig. 2g, where double peaks were located at 952.45 eV and 932.63 eV, corresponding to Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 binding energies of metallic Cu, respectively [40,41]. The high resolution Cu 2p spectra of C/Cu-Ti on surface is similar to that of Cu-Ti (Fig. 2f). Double peaks (Fig. 2h) of Cu 2p at 30 nm depth were positioned at 952.45 eV and 932.67 eV respectively, which corresponded to Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 binding energies of metallic Cu respectively [41,42]. The above results indicate copper existed on both surface and inside of C/Cu–Ti and C–Ti.

Ti 2p high-resolution XPS on surfaces and inside of different samples are displayed in Fig. 3. As shown from Fig. 3a, there were four fitting peaks in Ti 2p high-resolution spectrum on surface of the C–Ti. Two main peaks located at 458.20 eV and 464.19 eV, corresponding to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies in TiO2, respectively [43,44]. And two peaks at 462.00 eV and 455.90 eV corresponded to Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2 in Ti2O3[45,46], respectively. Fig. 3b shows high-resolution spectrum of Ti 2p at 30nm depth of C-Ti and six peaks can be found. Two main peaks were located at 454.20 eV and 460.20 eV corresponding to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of Ti-C [[47], [48]]. Peaks at 456.10 eV and 461.50 eV corresponded to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of Ti2+ respectively [[49], [50]]. Two peaks located at 457.73 eV and 463.52 eV presented Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of TiO2 respectively [51].

Fig. 3.

XPS high-resolution spectra of Ti 2p obtained from surfaces (a, c and e) and inside of C–Ti, Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti at 30 nm depth (b, d and f).

Ti 2p peaks on surface of Cu–Ti were situated at 458.33 eV and 464.19 eV, corresponding to Ti 2p3/2 [52] and Ti 2p1/2 [44] binding energies of TiO2 (Fig. 3c). There were six peaks in Ti 2p high-resolution spectrum of Cu-Ti at 30 nm depth (Fig. 3d). Two peaks were located at 454.70 eV and 460.20 eV corresponding to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of metallic Ti [[53], [54]]. It has been reported that Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 peaks (about 454 eV and 460 eV) of Ti-C overlapped with those of pure Ti [[55], [56]]. Thus, we resolve these peaks according to specific experiments and C 1s high resolution of samples. Two peaks situated at 458.06 eV and 463.65 eV corresponded to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of TiO2 respectively [57]. The other two peaks which were positioned at 456.52 eV and 462.00 eV corresponded to Ti3+ [58].

Ti 2p high-resolution spectrum on surface of C/Cu–Ti is shown in Fig. 3e. Two peaks located at 458.20 eV and 464.00 eV corresponded to binding energies of Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 in TiO2 [59]. Fig. 3f displays high-resolution spectrum of Ti 2p at 30nm depth of C/Cu-Ti. Two peaks at 454.20 eV and 460.00 eV corresponded to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of Ti-C [48]. Double peaks at 457.73 eV and 463.52 eV corresponded to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies of TiO2 [51]. The other two peaks at 456.10 eV and 461.50 eV corresponded to Ti2+ [[49], [50]].

These results indicate titanium element mainly existed on C–Ti, Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti in the form of TiO2, while it mainly existed as titanium carbide and/or pure titanium at the depth of 30 nm inside C–Ti, Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti.

3.2. Surface wettability

The measured water contact angles of different samples are shown in Fig. 4. Ti, C–Ti, Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti samples’ contact angles were 52.5 ± 4.0°, 46.6 ± 3.6°, 50.7 ± 2.4° and 49.6 ± 1.3° respectively. There is no obvious difference among these groups, indicating that the surface wettability could not be changed by ion implantation.

Fig. 4.

Water contact angles measured from various surfaces.

Fig. 5 displays the release curves of Cu2+ of Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti immersed in PBS for two weeks. It can be seen that as the immersion time extended, Cu2+ concentration was increased. And the amount of copper ions released from C/Cu–Ti was more than that from Cu–Ti.

Fig. 5.

Cu2+ release curves from Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti immersed in PBS for two weeks.

Fig. 6 and Table 3 show curves of polarization and relevant data of samples in physiological saline before and after modification. The corrosion potentials of modified samples (C–Ti, Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti) all showed positive shift (shown by the red arrow), indicating anticorrosion performances of modified samples were improved. Anticorrosion performance of C–Ti was improved due to amorphous carbon formed on surface and TiC inside C–Ti [20,22].

Fig. 6.

Polarization curves of various samples.

Table 3.

Corrosion potentials and currents of various samples.

| Ti | C–Ti | Cu–Ti | C/Cu–Ti | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecorr (V) vs. SCE | −0.489 | −0.247 | −0.239 | −0.213 |

| Icorr (A cm−2) | 2.630 × 10−7 | 7.943 × 10−7 | 3.981 × 10−6 | 3.459 × 10−6 |

After copper ions implantation, copper oxide existed on Cu–Ti. It has been reported that copper oxide had good corrosion resistance [60], thus the corrosion potential of Cu–Ti could be larger than that of Ti surface. The reason why the corrosion resistance of titanium surface can be enhanced by C/Cu co-implantation may be that the standard electrode potential of nano-scale TiO2 film was −0.502 V [61], and the standard electrode potential of Cu is +0.34 V [29], while amorphous carbon with stable chemical properties existed on the surface. The amorphous carbon film has an amorphous metastable structure containing sp2 carbon and sp3 carbon [62]. Amorphous carbon contains a certain amount of free electrons from the sp2 hybrid, so it has conductive property. Owing to low electron affinity and chemical inertness, amorphous carbon is a strong candidate for cathode [63].

According to the corrosion principle of electrochemistry, a C/Cu galvanic corrosion pair could be formed in a liquid environment. Cu would preferentially act as the anode where Cu2+ions were relesed, while C would be the cathode, and the TiO2 layer was the path of electronic transmission. As a result of the above reaction, the Ti substrate was protected and the corrosion resistance was improved.

The specific reactions take below:

| Cu (anode): Cu → Cu2+ + 2e− | (5) |

| C (cathode): 2H+ + 2e− → H2 | (6) |

| O2 + 4H+ + 4e− → 2H2O | (7) |

The surface zeta potential values of various samples are displayed in Fig. 7. As pH value of KCl electrolyte increased, zeta potential of all the samples tended to decrease. When pH value was 7.4, all the surfaces were negatively charged, and the values of Ti, C–Ti, Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti were −76.7 mV, −104.6 mV, −59.6 mV and −50.9 mV, respectively. Zeta potential of C–Ti sample was more negative than that of Ti, which may be related to the existence of amorphous carbon on such simple surface. The combination of carbon atoms in amorphous carbon included both SP3 hybridization and SP2 hybridization of carbon atoms [64]. Therefore, C–Ti surface contained negatively charged free electrons, which may cause the zeta potential of C–Ti surface to be lower than that of Ti surface. Zeta potential value of C/Cu–Ti surface was slightly positive than that of Cu–Ti. The reason may be that more copper ions with positive charges were released from C/Cu–Ti surface at pH 7.4. (The zeta potential values of Ti surface cited data from previous studies [30]).

Fig. 7.

Surface zeta potential values of different samples at various pH values.

Fig. 8 displays nano-hardness curves of the sample surfaces. Surface hardness of samples with ion implantation tended to increase in comparison with pure Ti, especially for C/Cu–Ti and C–Ti samples, which may be caused by high hardness of TiC on their surfaces. Copper implantation could slightly increase the nano-hardness value of Ti surface, possibly because of the existence of interior metallic copper [65].

Fig. 8.

Hardness average values of various samples at the depth from 40 nm to 60 nm.

The curves in nano-hardness of surfaces of the samples with depth are exhibited in Fig. 9. In general, nano-hardness value of C/Cu–Ti was the largest, rising to the peak at 22 nm (about 13 Gpa), before dropping generally to around 9 Gpa at 60 nm. And nano-hardness values of Cu–Ti and C–Ti were larger than that of Ti, so the nano-hardness value of Ti surface could be increased significantly by carbon/copper ions co-implantation, and the result was consistent with the trend showed in Fig. 8. (The nano-hardness data of Ti surface cited data from previous studies [30]).

Fig. 9.

Nano-hardness curves of various samples.

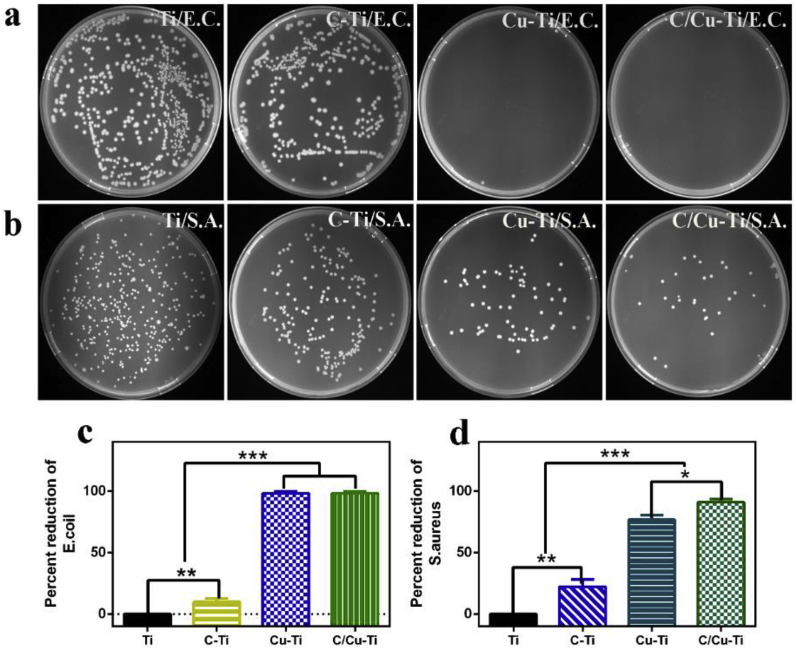

3.3. Antibacterial ability

The antibacterial ability of different samples against E. coli and S. aureus was quantitatively studied through plate counting method. The number of bacterial colonies on C–Ti or Ti was evidently more than that on C/Cu–Ti or Cu–Ti (Fig. 10a and b). According to Fig. 10c and d, inhibition rates to S. aureus and E. coli on surface of C–Ti were about 20% and 10%, respectively, indicating the weak antibacterial ability of C–Ti. This phenomenon would be explained below in conjunction with SEM morphologies of bacteria. The percent reductions of E. coli on both surfaces of Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti were about 100%. On the other hand, antibacterial rate of C/Cu–Ti against S. aureus was about 90%, and that of Cu–Ti was 75%. The results demonstrated that antibacterial properties of C/Cu-Ti were superior to the single Cu ion implantation (Cu–Ti).

Fig. 10.

Images of E. coli and S. aureus colonies on surfaces of different samples: E. coli (a) and S. aureus (b); Percent reductions of bacteria re-cultivated on agar: E. coli (c) and S. aureus (d). (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Fig. 11, Fig. 12 show SEM morphologies of E. coli and S. aureus after 24h cultivation on various surfaces. On pure Ti surface, a large number of E. coli and S. aureus grew well, while the number of bacteria on C–Ti surface was slightly decreased. The adhesion of bacteria on the material surface mainly includes 2 stages: at the first stage, the initial physical and chemical interaction happens; the second stage is the interaction of molecules and bacteria [66]. Among the various interface parameters of materials, surface roughness and chemical composition are considered as two important factors related to the interaction between materials and bacteria. Before and after C-PIII&D modification, the sample's surface morphology did not show obvious change. Therefore, the surface roughness of the sample had negligible effect on bacteria adhesion, and bacteria adhesion was mainly controlled by the chemical composition of sample surface. According to the XPS results, the main component of the surface modified by C-PIII&D was amorphous carbon, which was chemically inert. It weakened the chemical action of the sample and bacteria, thus inhibited bacterial adhesion [26,27]. Secondly, according to Fig. 7, the zeta potential value of C–Ti was lower than that of pure Ti sample at pH 7.4. Since bacterial membrane was negatively charged, C–Ti sample inhibited bacterial adhesion due to a stronger electrostatic repulsion. Therefore, the inhibition of bacterial adhesion by carbon ion implantation samples was considered to be the result of the combination of the larger chemical inertness of the surface carbon film and the negative surface potential. As shown in Fig. 11, compared with Ti and C–Ti, fewer complete bacterial individuals were found on both surfaces of Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti, and most E. coli had been split and dead, which indicated good antibacterial properties of those surfaces against E. coli.

Fig. 11.

SEM morphology of E. coli seeded on different surfaces after incubation for 24 h.

Fig. 12.

SEM morphology of S. aureus seeded on different surfaces after incubation for 24 h.

In Fig. 12, a large number of S. aureus, which grew well and had spherical shape, existed on Ti surface. However, some of the S. aureus with obvious dryness and flatness shape were on Cu–Ti. Moreover, more membranes of S. aureus on C/Cu–Ti were damaged, indicating that C/Cu dual ions implantation showed good antibacterial effect against S. aureus. The results above were consistent with the previous results shown in Fig. 10.

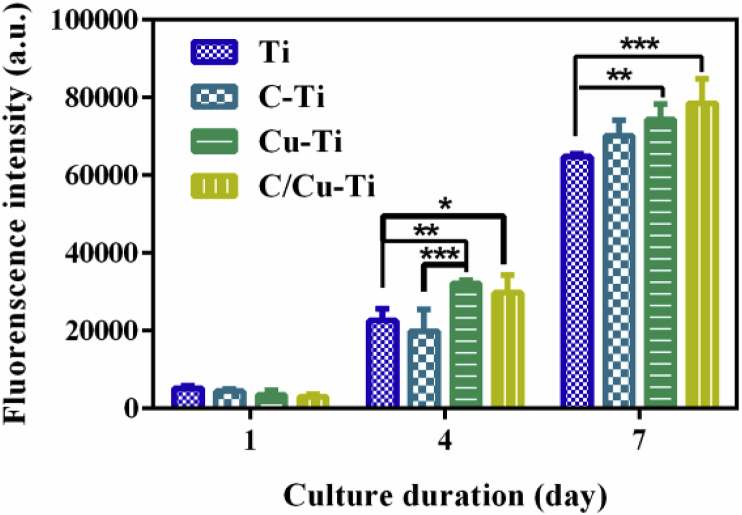

3.4. Cytotoxicity

Fig. 13 exhibits proliferation activity of mouse osteoblast MC3T3-E1 on different sample surfaces. It can be seen that cell activities on Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti were slightly higher than those on Ti and C–Ti, and this can be ascribed to the small amount of released copper ions. In our previous study, we have investigated the dose-response relationship between copper and its biocompatibilities, and the results showed that copper ions can stimulate the proliferation of MC3T3-E1 within the concentration of about 12.34 μM (0.8 ppm) [67]. As shown in Fig. 5, the accumulated concentration of copper ions for Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti is less than 0.2 ppm after 14 days incubation, indicating Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti have good cytocompatibility to MC3T3-E1.

Fig. 13.

Proliferative activity of MC3T3-E1 cultured on various surfaces for several days.

Schematic diagram of possible antibacterial mechanism on the surface of C/Cu co-implanted titanium is shown in Fig. 14. Amorphous carbon with chemical stability existed and the standard electrode potential of titanium dioxide is significantly more negative than that of copper, so Cu phase tends to serve as an anode releasing Cu2+, and amorphous carbon serves as a cathode. As a result, more Cu2+ could be released from the C/Cu–Ti surface than those from Cu–Ti surface. Burghardt et al. revealed that copper ions are not cytotoxic and could effectively kill bacteria, if its concentration is controlled within 10 mg/L [68]. In this experiment, there is less than 10 mg/L Cu2+ released from Cu–Ti and C/Cu–Ti, and more copper ions within the save limitation can thus enter the microenvironment between the sample's surface and bacteria to improve its antibacterial ability.

Fig. 14.

Schematic diagram of possible antibacterial mechanism on titanium surface after C/Cu co-implantation.

Besides, carbon acts as the cathode where a hydrogen evolution reaction and a reduction of dissolved oxygen take place, and these reactions can consume hydrogen ions (protons) in the microenvironment. Proton concentration ladder inside and outside the bacterial cell membrane is then affected [28]. The reduction of proton outside membrane will inevitably affect the process of ATP synthesis where protons transported from the outside of membrane are needed, which may cause bacteria to have insufficient energy and eventually lead to bacterial death [61]. “Synergistic effect” brought by C/Cu dual ions implantation can display good antibacterial effects without causing cytotoxicity.

4. Conclusion

After C/Cu co-implantation, titanium surface mainly contained amorphous carbon and copper-bearing nano-particles, and TiC phase existed in near surface layer. C/Cu ions implantation could improve mechanical properties of Ti surface, which was mainly attributed to the effect of TiC phase. C/Cu ions implanted Ti surface could form Cu/C galvanic corrosion pairs, in which Cu served as anode, and C acted as cathode, thereby protecting the Ti surface and improving anti-corrosion performance of Ti surface. Copper ion release was controlled and resistance of Ti surface to bacteria was effectively improved by effect of galvanic corrosion, and Ti surface was free of cytotoxicity after C/Cu ions were implanted.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1100604), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570973, 31870944 and 51831011), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (19JC1415500), Science Foundation for Youth Scholar of State Key Laboratory of High Performance Ceramics and Superfine Microstructures (SKL201606) are acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Contributor Information

Yuqin Qiao, Email: qiaoyq@mail.sic.ac.cn.

Xuanyong Liu, Email: xyliu@mail.sic.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Hooper G. The ageing population and the increasing demand for joint replacement. N. Z. Med. J. 2013;126(1377):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen Gang, Zhang Ju-Fan, Fang Feng-Zhou. In vitro evaluation of artificial joints: a comprehensive review. Adv. Manuf. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Ji, Wang Ketao, Li Zhongli. Mechanical tests, wear simulation and wear particle analysis of carbon-based nanomultilayer coatings on Ti 6 Al 4 V alloys as hip prostheses. RSC Adv. 2018;8(13):6849–6857. doi: 10.1039/c7ra12080j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Chu P K, Ding C. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications[J]. Mater. Sci. Eng. Rep., 47(3):49-121.

- 5.Ge S.R., Wang Q.L. Investigation on the biotribology of the modified artificial joint materials. J. Med. Biomech. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raphel J., Karlsson J., Galli S. Engineered protein coatings to improve the osseointegration of dental and orthopaedic implants. Biomaterials. 2016;83:269–282. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peddi L., Brow R.K., Brown R.F. Bioactive borate glass coatings for titanium alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008;19(9):3145–3152. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solar R.J., Pollack S.R., Korostoff E. In vitro corrosion testing of titanium surgical implant alloys: an approach to understanding titanium release from implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1979;13(2):217–250. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan J., Leygraf C., Thierry D. Corrosion resistance for biomaterial applications of TiO2 films deposited on titanium and stainless steel by ion-beam-assisted sputtering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997;35(3):309–318. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970605)35:3<309::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J., Li J., Qian S. Antibacterial surface design of titanium-based biomaterials for enhanced bacteria-killing and cell-assisting functions against periprosthetic joint infection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b02803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joska L., Fojt J., Cvrcek L. Properties of titanium-alloyed DLC layers for medical applications. Biomatter. 2014;4(1) doi: 10.4161/biom.29505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen M., Myer B., Rushton N. In Vitro and in vivo investigations into the biocompatibility of Diamond-Like carbon (DLC) coatings for Orthopedic Applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;58(3):319–328. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(2001)58:3<319::aid-jbm1024>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed M.H., Byrne J.A. Effect of surface structure and wettability of DLC and N-DLC thin films on adsorption of glycine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012;258(12):5166–5174. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul R., Gayen R.N., Hussain S. Synthesis and characterization of composite films of silver nanoparticles embedded in DLC matrix prepared by plasma CVD technique. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2009;47(1):10502. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lukaszkowicz K., Sondor J., Balin K. Characteristics of CrAlSiN + DLC coating deposited by lateral rotating cathode arc PVD and PACVD process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014;312:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oka Y., Kirinuki M., Suzuki T. Effect of ion beam implantation on density of DLC prepared by plasma-based ion implantation and deposition. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B. 2006;242(1–2):335–337. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baba K., Hatada R. Preparation and properties of nitrogen and titanium oxide incorporated diamond-like carbon films by plasma source ion implantation. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2001;136(1–3):192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng F., Li Z., Liu X. Synthesis of tantalum thin films on titanium by plasma immersion ion implantation and deposition. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2013;229:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin G., Cao H., Qiao Y. Osteogenic activity and antibacterial effect of zinc ion implanted titanium. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2014;117(9):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y., Wong S.M., Wong H.M. Effects of carbon and nitrogen plasma immersion ion implantation on in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of titanium alloy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5(4):1510–1516. doi: 10.1021/am302961h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poon R., Yeung K., Liu X. Carbon plasma immersion ion implantation of nickel-titanium shape memory alloys. Biomaterials. 2005;26(15):2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sui J.H., Gao Z.Y., Cai W. DLC films fabricated by plasma immersion ion implantation and deposition on the NiTi alloys for improving their corrosion resistance and biocompatibility. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2007;454(16):472–476. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia Chao, Qian Shi, Wang Donghui. Properties of carbon ion implanted biomedical titanium. Acta Metall. Sin. 2017;53(10):1393–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharifahmadian O., Salimijazi H.R., Fathi M.H., Mostaghimi J., Pershin L. Relationship between surface properties and antibacterial behavior of wire arc spray copper coatings. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2013;233:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akhavan O., Ghaderi E. Cu and CuO nanoparticles immobilized by silica thin films as antibacterial materials and photocatalysts. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2010;205(1):219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J., Huang N., Yang P. The effects of amorphous carbon films deposited on polyethylene terephthalate on bacterial adhesion. Biomaterials. 2004;25(16):3163–3170. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J., Pan C.J., Li P. Antibacterial properties of amorphous carbon films deposited on polyethylene terephthalate by C2H2 plasma immersion ion implantation-deposition. J. Funct. Mater. 2004;35(5):563–565. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao H., Liu X., Meng F., Chu P.K. Biological actions of silver nanoparticles embedded in titanium controlled by micro-galvanic effects. Biomaterials. 2011;32:693. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu L., Jin G., Ouyang L. Antibacterial activity, osteogenic and angiogenic behaviors of copper-bearing titanium synthesized by PIII&D. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2016;4(7):1296–1309. doi: 10.1039/c5tb02300a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia Chao, Cai Dingsen, Tan Ji. Synergistic effects of N/Cu dual ions implantation on stimulating antibacterial ability and angiogenic activity of titanium. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018;4:3185–3193. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shakerzadeh M., Teo H.T.Edwin, Tan C.W., Tay B.K. Superhydrophobic carbon nanotube/amorphous carbon nanosphere hybrid film. Diamond and Related Materials. 2009;18(10):1235–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hrbek J. Carbonaceous overlayers on Ru(001) J. Vac. Sci. Technol. Vac. Surface. Films. 1986;4(1):86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ihara H., Kumashiro Y., Itoh A. Some aspects of ESCA spectra of single crystals and thin films of titanium carbide. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1973;12(9):1462–1463. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaillard C., Lepez-Heredia M.A., Legeay G., Layrolle P. Raio Frequency Plasma Treatments on Titanium for Enhancement of Bioactivity. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008;4(6):1953–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schön G. ESCA studies of Cu, Cu2O and CuO. Surf. Sci. 1973;35(1):96–108. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller A.C., Simmons G.W. Copper by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra. 1993;2(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura T., Tomizuka H., Takahashi M. Methods of powder sample mounting and their evaluations in XPS analysis. Hyomen. Kagaku. 1995;16(8):515–520. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jolley J.G., Geesey G.G., Hankins M.R. Auger electron and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic study of the biocorrosion of copper by alginic acid polysaccharide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1989;37(4):469–480. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parmigiani F., Pacchioni G., Illas F. Studies of the Cu-O bond in cupric oxide by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and ab initio electronic structure models. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1992;59(3):255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bird R.J., Swift P. Energy calibration in electron spectroscopy and the re-determination of some reference electron binding energies. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1980;21(3):227–240. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller A.C., Simmons G.W. Copper by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra. 1993;2(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seah M.P., Anthony M.T. Quantitative XPS: the calibration of spectrometer intensity-energy response functions-the establishment of reference procedures and instrument behaviour. Surf. Interface Anal. 1984;6(5):230–241. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dementjev A.P., Ivanova O.P., Vasilyev L.A. Altered layer as sensitive initial chemical state indicator. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. Vac. Surface. Films. 1994;12(2):423–427. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanjines R., Tang H., Berger H. Electronic structure of anatase TiO2 oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 1994;75(6):2945. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonbeau D., Guimon C., Pfister-Guillouzo G. XPS study of thin films of titanium oxysulfides. Surf. Sci. 1991;254(1–3):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan Z.N., Cai R., Jiang S.M., Shao Z.P. Nitrogen- and TiN-modified Li4Ti5O12: one-step synthesis and electrochemical performance optimization. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2012;22:17773–17781. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devia D.M., Parra E.R., Arango P.J. Comparative study of titanium carbide and nitride coatings grown by cathodic vacuum arc technique. Applied Surface Science. 2011;258(3):1164–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leesungbok R., Lee M.H., Oh N., Lee S.W., Kim S.E., Yun Y.P., Kang J.H. Factors influencing osteoblast maturation on microgrooved titanium substrata. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):3804–3815. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prehn E.M., Echols I.J., An H.S., Zhao X.F., Tan Z.Y., Radovic M., Green M.J., Lutkenhaus J.L. pH-Response of polycation/Ti3C2Tx MXene layer-by-layer assemblies for use as resistive sensors. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering. 2020;5:366–375. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye H.Z., Liu X.Y., Hong H.P. Cladding of titanium/hydroxyapatite composites onto Ti6Al4V for load-bearing implant applications. Materials Science and Engineering. 2009;29(6):2036–2044. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yassin J.M., Zelekew O.A., Kuo D.H., Ahmed K.E., Abdullah H. Synthesis of efficient silica supported TiO2/Ag2O heterostructured catalyst with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Applied Surface Science. 2017;410:454–463. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Netterfield R.P., Martin P.J., Pacey C.G. Ion‐assisted deposition of mixed TiO2‐SiO2 films. J. Appl. Phys. 1989;66(4):1805–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rao A.P., Sunandana C.S. Growth and surface morphology of ion-beam sputtered Ti–Ni thin films. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms. 2008;266(8):1517–1521. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding X., Wang G.F., Li J.H., Lv K.G., Zhang W.J., Yang G.Z., Liu X.Y., Jiang X.Q. Surface thermal oxidation on titanium implants to enhance osteogenic activity and in vivo osseointegration. Scientific Reports. 2006;6:31769. doi: 10.1038/srep31769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Green S.M., Grant D.M., Wood J.V. XPS characterisation of surface modified Ni-Ti shape memory alloy. Materials Science and Engineering. 1997;224(1–2):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glaub J.E., Bruke A.R., Brown C.R., Bowling W.C., Kapsch D., Love C.M., Whitaker R.B., Moddeman W.F. Ignition mechanism of the titanium–boron pyrotechnic mixture. Surface and Interface Analysis. 1988;11(6–7):353–358. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gan B.L., Leong K.H., Ibrahim S., Saravanan P. Synthesis of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) triggered Ag/TiO2 photocatalyst for degradation of endocrine disturbing compounds. Applied Surface Science. 2014;319:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samoila F., Tiron V., Velicu I.L., Dobromir M., Demeter A., Ursu C., Sirghi L. Reactive multi-pulse HiPIMS deposition of oxygen-deficient TiOx thin films. Thin Solid Films. 2016;603:255–261. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng J.Y., Wan L., Li J.F., Sun W., Mao Z.Q. Improved optical response and photocatalysis for N-doped titanium oxide (TiO2) films prepared by oxidation of TiN. Applied Surface Science. 2007;253(10):4764–4767. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adeloju B., Duan Y.Y. Corrosion resistance of Cu2O and CuO on copper surfaces in aqueous media. Br. Corrosion J. 1994;29(4):309–314. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jin G., Qin H., Cao H. Synergistic effects of dual Zn/Ag ion implantation in osteogenic activity and antibacterial ability of titanium. Biomaterials. 2014;35(27):7699–7713. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robertson J. Diamond-like amorphous carbon. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2002;37(4-6):129–281. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robertson J. Amorphous carbon cathodes for field emission display. Thin Solid Films. 1997;296(1–2):61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Díaz Javier, Paolicelli G., Ferrer S. Separation of the sp3 and sp2 components in the C1s photoemission spectra of amorphous carbon films. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54(11):8064–8069. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.8064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang S., Ma Z., Liao Z. Study on improved tribological properties by alloying copper to CP-Ti and Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.An Y.H., Friedman R.J. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterial surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998;43(3):338–348. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199823)43:3<338::aid-jbm16>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Kunqiang, Xia Chao, Qiao Yuqin, Liu Xuanyong. Dose-response relationships between copper and its biocompatibility/antibacterial activities. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019;55:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2019.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burghardt I., Lüthen Frank, Prinz C. A dual function of copper in designing regenerative implants. Biomaterials. 2015;44:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]