Abstract

Millions of individuals worldwide suffer from impaired vision, a condition with multiple origins that often impinge upon the light sensing cells of the retina, the photoreceptors, affecting their integrity. The molecular components contributing to this integrity are however not yet fully understood. Here we have asked whether Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 1 (SFRP1) may be one of such factors. SFRP1 has a context-dependent function as modulator of Wnt signalling or of the proteolytic activity of A Disintegrin And Metalloproteases (ADAM) 10, a main regulator of neural cell-cell communication. We report that in Sfrp1−/− mice, the outer limiting membrane (OLM) is discontinuous and the photoreceptors disorganized and more prone to light-induced damage. Sfrp1 loss significantly enhances the effect of the Rpe65Leu450Leu genetic variant -present in the mouse genetic background- which confers sensitivity to light-induced stress. These alterations worsen with age, affect visual function and are associated to an increased proteolysis of Protocadherin 21 (PCDH21), localized at the photoreceptor outer segment, and N-cadherin, an OLM component. We thus propose that SFRP1 contributes to photoreceptor fitness with a mechanism that involves the maintenance of OLM integrity. These conclusions are discussed in view of the broader implication of SFRP1 in neurodegeneration and aging.

Subject terms: Cellular neuroscience, Retinal diseases

Introduction

Photoreceptors are specialized neurons localized in the outermost layer of the retina, which are responsible for converting light information into electrical activity. There are two types of photoreceptors: cones that mediate vision in bright light (photopic vision), and rods that support vision in dim light (scotopic vision). Each photoreceptor develops a highly modified cilium, the outer segment (OS), composed of a stack of membranes that contains light-sensing visual pigments and other photo-transduction proteins connected to the photoreceptor cell body by the inner segment (IS). The organization, polarity and function of these specialized structures is assured at the proximal side by the presence of the outer limiting membrane (OLM), composed of a series of adherens junctions between the initial portion of the IS and the neighbouring Müller glial end-feet. At the distal side, instead, the OSs are in contact with the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a monolayer of cells that daily phagocyte the OS abutting portion and provides metabolic support to the photoreceptors1. Thus, the physiology of photoreceptors is critically dependent, among others, on their interaction with adjacent non-neuronal cell types. Environmental, age-related and genetic defects disrupting these interactions lead to the progressive death of photoreceptors and thereby to the progressive loss of sight, often followed by total blindness2. Indeed, loss of OLM integrity is commonly observed in different forms of retinal dystrophies, including Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP)2, a collection of monogenic disorders characterized by a tremendous genetic heterogeneity3. Furthermore, RP causative genes include those coding proteins enriched at the OS and OLM, such as PCDH21 or Crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1)4–6 and even metalloproteases, such as ADAM97, known to cleave different cell adhesion molecules8,9. The molecular components that maintain photoreceptors’ interaction with the nearby tissues, thereby contributing to their integrity, are however not yet fully understood. The identification of such mechanisms may be instrumental in designing strategies for slowing down the progression of photoreceptors’ degeneration and perhaps explain the observed inter-individual variability of photoreceptor degeneration even among relatives carrying identical mutations or risk alleles10 in the case of genetic disorders.

We have recently shown that elevated levels of Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein (SFRP) 1- a secreted protein with the dual function of modulating Wnt signalling11 and regulating the enzymatic activity of the α-sheddase ADAM1012- contributes to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease13. Consistent with the notion that ADAM10 cleaves a large number of substrates -including the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and proteins involved in neuroinflammation and synaptic plasticity14,15-, high levels of SFRP1 prevent ADAM10-mediated non-amyloidogenic processing of APP13 and favour neuroinflammation16. Sfrp1 and its homologues Sfrp2 and Sfrp5 have been implicated in different aspects of eye and retinal development17–23. Furthermore, SFRP1 has been found to be expressed in the adult retina, mostly localized to the photoreceptor layer24, in contrast to what observed in the brain, in which SFRP1 expression is minimal in homeostatic conditions13,25. SFRPs genes are an unlikely primary cause of RP in humans26; however, their expression is notably increased and ectopically distributed in the retinas of patients with RP24,27. These observations, together with the notion that variation of SFRP expression has been noted in a variety of other pathological conditions28, made us ask whether SFRP1 may be involved in maintaining photoreceptors’ integrity.

Here we report that SFRP1 helps maintaining photoreceptor’s integrity. In its absence, photoreceptors of young and mature mice show subtle morphological alterations of the OS associated with discontinuities of the OLM and an increased proteolytical processing of two of its components: N-cadherin and PCDH21. Furthermore, Sfrp1 absence significantly increases the sensitivity of the photoreceptors to light-induced damage in the presence of the sensitizing Rpe65Leu450Leu gene variant, present in the genetic background of the mice.

Results

Young adult Sfrp1−/− retinas show subtle defects in cone photoreceptor organization

The final goal of our study was to determine whether SFRP1 is part of the molecular machinery that maintains photoreceptors’ integrity. We reasoned that, if this is the case, mice lacking SFRP1 activity (Sfrp1−/−) should have a different susceptibility than their wild type (wt) counterparts to light-induced damage, taken as a frequently used experimental paradigm to study photoreceptor degeneration29. Sfrp1 does not seem to be required for mouse retinal development 18,30,31. However, there are somewhat controversial reports on its adult retinal localization32,33 and, to our knowledge, no specific information on its possible function in adult retinal homeostasis. We addressed these issues first.

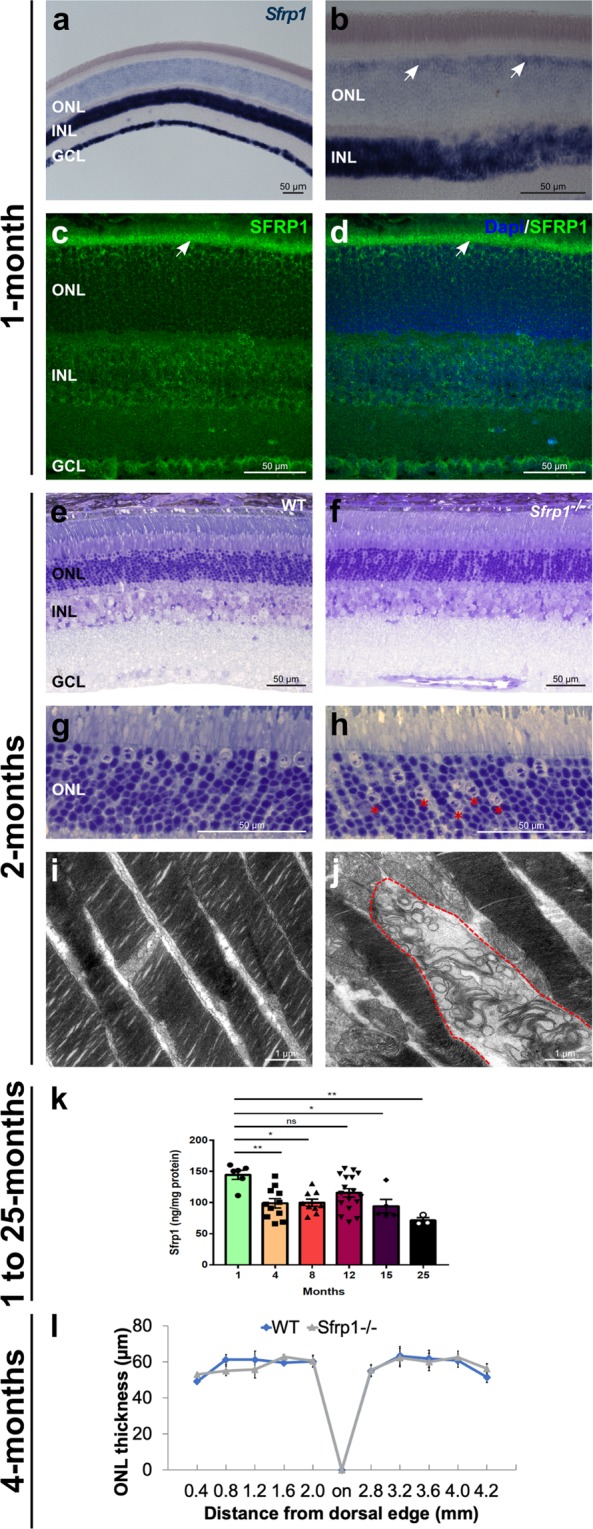

To clarify Sfrp1 distribution, we hybridized sections of 1 month-old mouse eyes with a specific probe. Our results supported the report by Liu et al.32. High levels of Sfrp1 were localized to the inner nuclear (INL) and ganglion cell (GCL) layers. Lower levels were also found in the outer nuclear (or photoreceptor) layer (ONL; Fig. 1a), with a more abundant distribution in a subset of cells located at the outermost region (Fig. 1b, white arrows), in which the cell bodies of cone photoreceptors are found34. Immunostaining with specific antibodies confirmed a similar layered distribution of the protein that, according to its secreted and dispersible nature18,35, was notably accumulated at the OLM/OS region (Fig. 1c,d). ELISA determination of SFRP1 content in retinal extracts from mice of age comprised between 1 and 25 months showed that its levels significantly decreased with age (Fig. 1k). In situ hybridization analysis did not detect the expression of the closely related Sfrp2 in the adult mouse retina as described for humans27, whereas Sfrp5 reporter expression was localized only in few sparse retinal cells and in the retinal pigmented epithelium (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

SFRP1 is expressed in the retina and required for photoreceptor fitness. (a–d) Frontal cryostat sections from 1 month-old wt animals hybridized (a,b), or immunostained (c,d) for SFRP1 and counterstained with DAPI. (d) The white arrows in (b) indicate the increased signal in the outermost region of the ONL. Note Sfrp1 accumulation in the OLM (arrows in c,d). (e–h) Semi-thin frontal sections from 2 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas stained with toluidine blue. Note the abnormal localization of cone nuclei in the mutant retina (red asterisks in h). (i,j) TEM analysis of the OS. Note that in the mutants, but not in wt, the stacks of membranes of the OS are disorganized (area enclosed in dotted line in (j). (k) ELISA analysis of SFRP1 levels in total protein extracts from 1 to 25 months-old retinas from wt mice. Note the significant decrease of SFRP1 content as the animals age; One-way ANOVA, with post hoc Bonferroni analysis; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (l) The graph shows the ONL thickness in 4 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas (measures were taken in cryostat frontal sections of the eye at the level of the optic disk). No significant differences were detected between wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas (Mann-Withney U test). Abbreviations: GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; on: optic nerve; ONL: outer nuclear layer.

To determine if the activity of SFRP1 is required for the organization of the adult retina, we compared the retinal morphology of 2 months-old Sfrp1−/− and wt mice using toluidine blue stained semi-thin sections. No appreciable gross differences were detected between the two genotypes and the thickness of the ONL layer was comparable in both the dorsal and ventral quadrants (Fig. 1e,f), even in 4 months-old mice (Fig. 1l; n = 3 mice/genotype, Mann-Whitney U test). In mice, cone cell bodies are mostly arranged in a single row below the OLM with nuclei characterized by the presence of 1–3 irregular clumps of heterochromatin. Rods instead occupy all the ONL rows with more densely stained nuclei and a single large central clump of heterochromatin34. This arrangement was easily recognizable in wt retinas observed at higher magnification (Fig. 1g), with 86.1% (±0.2) of the cones localized to the first or second row of the ONL, whereas the remaining 13.9% (±2.9) were found in other rows (n = 3 mice). In Sfrp1−/− retinas instead, cone nuclei were abnormally distributed (Fig. 1h, red asterisks) and only 51.1% (±6.2) of the cone cell bodies were found in the first two rows. The remaining 48.9% (±3.1) were distributed in other rows, with a significant cone increase in deeper rows (n = 3 mice; Chi-square test, p < 0.001). Nonetheless, the total number of cones was not significantly different between wt (291 ± 8, in nerve head sections, n = 3) and Sfrp1−/− mice (336 ± 13.5, n = 3; Mann-Whitney U test), at least in young adults. Nevertheless, ultra-structural analysis revealed occasional degenerative signs in the OS of the mutants, which were never observed in wt (Fig. 1i,j).

Sfrp1−/− mice were bred in a mixed C57BL/6 ×129 background. Previous studies have warned that C57BL/6 N sub-strain carries a single nucleotide deletion in the Crumb homologs 1 (Crb1) gene, which causes a retinal phenotype that may override that of other genes of interest36. Our animals were bread in the C57BL/6 J sub-strain, reported to carry a wt allele36. Nevertheless, and to confirm that the observed defects were bona fide associated to the loss of Sfrp1 function, we sequenced the Crb1 gene in the Sfrp1−/− line. No Crb1 mutations were found in all the analysed samples of our colony (not shown).

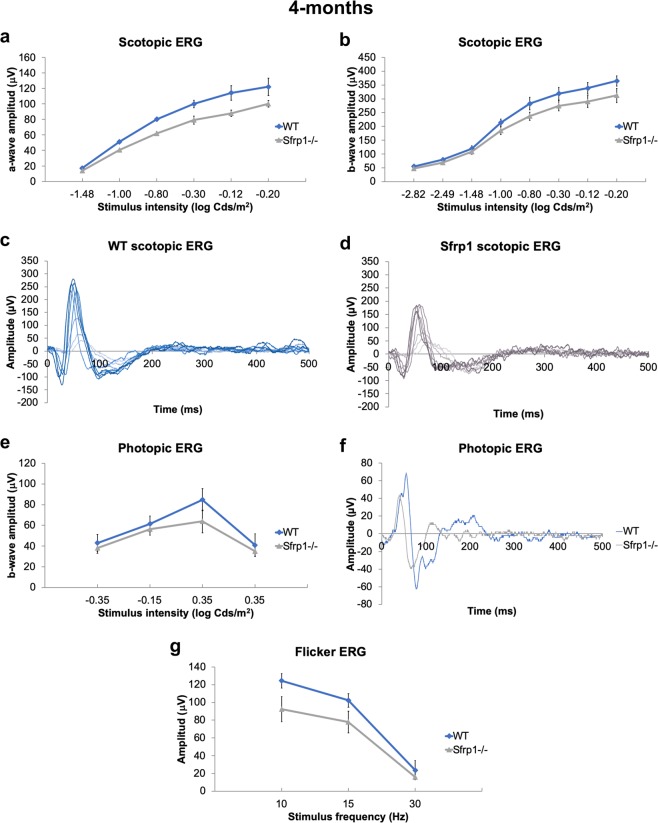

Once excluded the possible contribution of a defective Crb1 allele, we next asked if the subtle defects observed in Sfrp1−/− retinas had an impact on photo-transduction or synaptic transmission between photoreceptors and bipolar cells. To this end, we compared the electrical responses of groups of 4-months old wt and Sfrp1−/− mice (n = 12 per genotype) to light stimuli of increasing intensity and under increasing frequency. ERGs were recorded under scotopic (Fig. 2a–d) and photopic (Fig. 2e–g) conditions to evaluate rod/rod bipolar cells and cone/cone bipolar function, respectively. Mutant mice showed a small but statistically non-significant (Mann-Whitney U test) decrease of photoreceptor (a-wave, see Fig. S2) scotopic (Fig. 2c,d) and photopic (Fig. 1f) response at higher intensities and a tendency towards a lower response under flicker stimuli of low frequency (Fig. 2g).

Figure 2.

Sfrp1−/− mice have a slightly reduced visual function. (a–d) The graphs and traces of representative recordings show the a- and b-wave amplitude (µV; defined in Fig. S2) of the scotopic ERG (rods, a–d) and the b-wave amplitude of photopic ERG (cones, e,f) from 4 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− animals to flash light stimuli of increasing brightness (cd/m2). (e) The graph shows the amplitude response (µV) to flicker stimuli of increasing frequencies (Hz). No significant changes were detected (Mann-Whitney U test) but mutant mice show a reduced response.

Together these data suggest that SFRP1 contributes to maintain retinal organization but its absence has negligible effects on young adults.

Retinal disorganization and visual performance of Sfrp1−/− retinas worsen with age

Photoreceptors disorganization, decreased OS length and scotopic responses together with reduced synaptic density and loss of melanin granules are among the alterations found in the aging mammalian retinas37–39. The retinal phenotype of the young adult Sfrp1−/− mice shared some of these features, suggesting that the observed features could worsen with time.

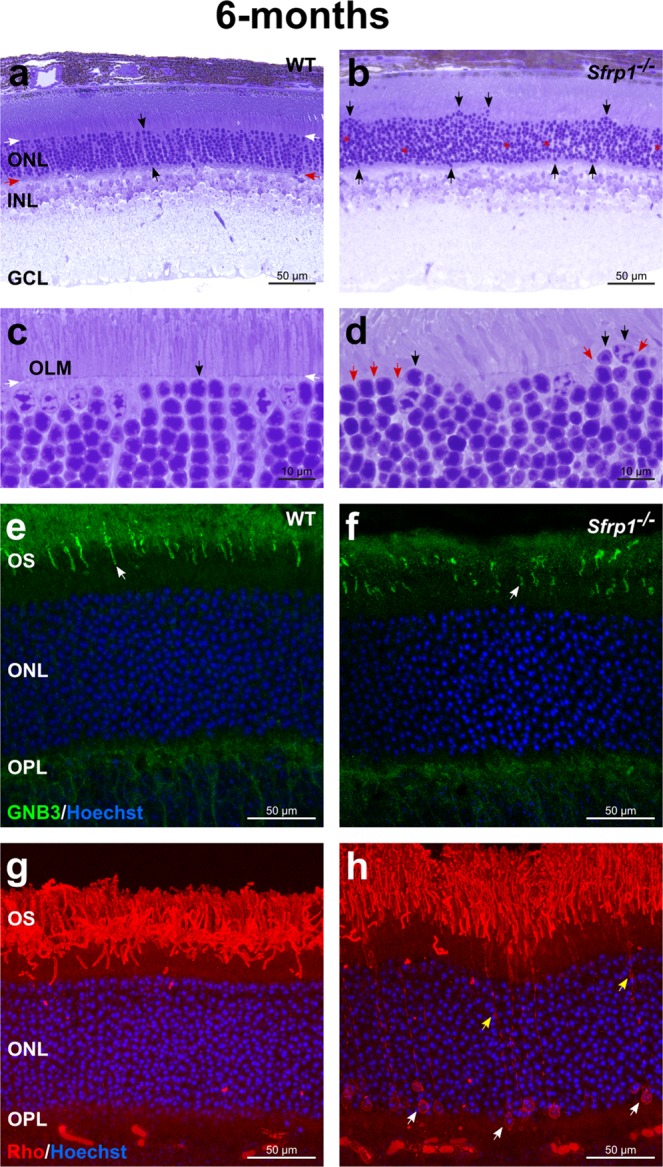

To address this possibility gross retinal morphology of 6 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− mice was analysed, finding no considerable macroscopic differences. However, the well-aligned columnar organization of the photoreceptors observed in wt was lost in the Sfrp1−/− retinas and, cone photoreceptor nuclei were distributed throughout the width of the ONL (Fig. 3a,b), as we observed in young mice. Many photoreceptors’ nuclei were also misplaced past the OLM that normally overlays the ONL (n = 6, Fig. 3c,d). Retinal immunostaining with the Transducin/GNB3 and rhodopsin (Rho), markers of the OS of cones and rods, respectively, confirmed subtle photoreceptors’ alterations. Transducin/GNB3 staining was particularly reduced and fragmented in the mutant retinas (n = 3 mice for each age, Fig. 3e,f), reflecting a small but significant reduction of the number of cone nuclei counted in toluidine blue stained sections (wt, 231.6 ± 12 vs. Sfrp1−/− 149 ± 26.7, in retinal nerve head sections; n = 3 and 5 mice, Mann Whitney U test, p = 0.025). In wt mice, Rho normally localises to the OS (Fig. 3g), but in the Sfrp1−/− retinas labelling was also observed in the cell bodies of a number of cells (Fig. 3h). Although ONL cell density was an obstacle for precise evaluation of the proportion of affected rods, cells with abnormal Rho distribution were consistently observed in both eyes of all the analysed animals (n = 3 mice for each age analysed, i.e., 6 and 8 month).

Figure 3.

Morphological alterations of Sfrp1−/− retinas become more evident with age. (a–d) Semi-thin plastic frontal sections from 6 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas stained with toluidine blue. Black arrows in a,c indicate an organized column of photoreceptors, whereas white and red arrows indicate the outer and inner limit of the ONL. In b and d black and red arrows point to misplaced photoreceptor nuclei and discontinuous OLM respectively. (e–h) Frontal cryostat sections from 6 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas immunostained with anti GNB3 (cones) or Rho (rods) antibodies and counterstained with Hoechst. White arrows in e,f point to the OS. Yellow and white arrows in h indicate accumulation of Rho in rod processes and cell bodies respectively. Abbreviations. GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; on: optic nerve; ONL: outer nuclear layer.

The presence of Rho in the cell bodies reflects cell intrinsic or OLM disturbances40. Indeed, the OLM seals off the photoreceptor inner and outer segments from the rest of the cell, thereby limiting the diffusion of the photo-transduction cascade components41. This notion together with the displacement of the photoreceptor nuclei (Fig. 3c,d), similar to that observed upon pharmacological disruption of the OLM 42,43, suggested the existence of OLM alterations in the mutants. The intermittent breakage of the OLM already apparent in histological sections (red arrows in Fig. 3d) was confirmed by ultrastructural analysis (n = 3). The well-organized arrangement of zonula adherens junctional complexes between the plasma membranes of the photoreceptor ISs and the apical processes of Müller glia that compose the OLM was readily visible in wt retinas (Fig. 4a). This arrangement was no longer present in those regions of the Sfrp1−/− retinas in which photoreceptors’ nuclei were displaced bearing signs of degeneration in both the cell body (Fig. 4b) and OS. Defective outer segments were more abundant than those observed at 2 months of age (Fig. 1j) and mostly localized in the central retina as determined by quantification in semi-thin sections (Fig. 4c,d; 5 ± 1 in wt and 25 ± 3 in Sfrp1−/− nerve head sections, n = 3, Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.043). In Sfrp1−/− retinas, RPE cells presented less and smaller melanosomes (Fig. 4e,f) and synaptic contacts between photoreceptors and bipolar interneurons were also altered, with an abnormal accumulation of synaptic vesicles (Fig. 4h) and the degeneration of pre and post- synaptic terminals (red arrows in Fig. 4i,j). None of these defects were observed in wt retinas (Fig. 4g) but have been reported in aging retinas37–39.

Figure 4.

OLM is disrupted in the retina of Sfrp1−/− mice in association with an impoverishment of visual function. (a,b; e–j) TEM analysis of the retina from 6 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− mice. Images show the OLM (a,b), RPE (e,f) and photoreceptor-bipolar cells synapses (g–j). White arrows in a,b point to adherens junctions between Müller glial cell end-feet (red asterisks) and photoreceptors (black asterisks). White arrows in e,f point to melanosomes. Red arrows in i,j indicate synaptic terminal disorganization. (c,d) Semi-thin frontal sections from 6 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas stained with toluidine blue. Note the abnormal presence of degenerating outer segments in the mutant retina (red arrows in d). (k,l) The graphs show the ERG recordings of rods and rod bipolar cells (scotopic, k,l) and cone –pathway (photopic, m) response to light of 9 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− animals. (n) The graph represents the activity of photoreceptors from 4 and 9 months-old Sfrp1−/− mice. Note that activity is expressed as a percentage of wt age-matched animals. Only 9 months-old Sfrp1 mice showed a significantly reduced activity relative to their control. (o) Semi-thin frontal sections from 10 months-old Sfrp1−/− retina stained with toluidine blue. Note the continuous presence of degenerating (red arrows) and enlarged OS with evident breakage of the OLM (white arrows); (p) The graphs represent the thickness of the ONL in 12 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas showing a significant reduction in the mutants more evident in central regions. Mann-Whitney U test; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Abbreviations. bc: bipolar cell; hc: horizontal cell; r ribbon; sv: synaptic vesicles.

Recording of ERGs responses (Fig. S2) under scotopic (Fig. 4k,l) and photopic (Fig. 4m,n) conditions in 9 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− mice showed that the above described morphological defects of Sfrp1−/− mice were associated with a poorer performance of rods as compared to wt mice (Fig. 4k; n = 5 per genotype, Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.035). Direct comparison of the photopic responses of 4 and 9 months-old Sfrp1−/− mice indicated a progressive deterioration with aging (Fig. 4n; Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.033).

Morphological analysis of 12 months-old mice showed worsening of photoreceptor damage with enlarged and degenerated OS and an evident breakage of the OLM (Fig. 4o). Overall, the thickness of ONL was significantly reduced (20% on average) across the almost entire dorso-ventral axis of the retinas as compared to age-matched wt (Fig. 4p; n = 5 per genotype, Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05).

Together these data indicate that Sfrp1 loss causes a slow but progressive deterioration of the retinal integrity associated with decrease of visual function.

The proteolysis of OLM and OS components is increased in Sfrp1−/− retinas

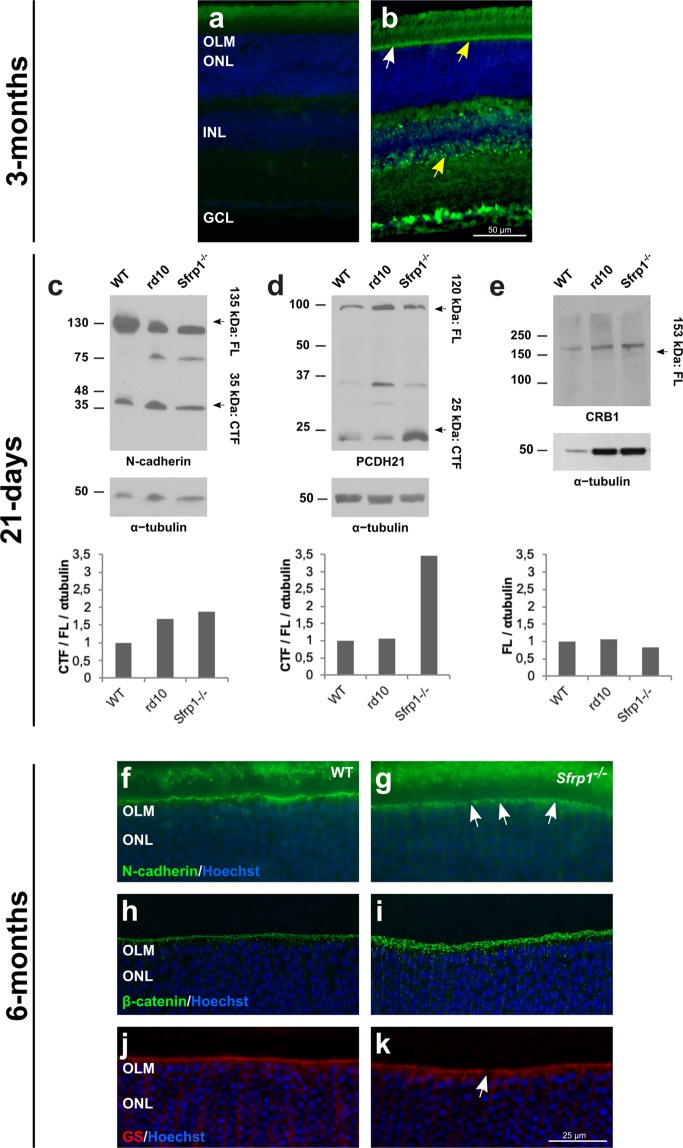

The region of the OLM is enriched in cell adhesion molecules, such as N-cadherin found at the adherens junctions44 and protocadherin PCDH21, located at the base of the OS45. Other transmembrane molecules are, for example, CRB2 and CRB1, found at the subapical region (right above the adherens junctions) of the photoreceptors and/or Müller glial cells as part of a large protein complex6,46. As already mentioned, a tight adhesion between IS of the photoreceptors and the end feet of the Müller cells is critical for photoreceptor integrity and retinal organization47. Furthermore, variation of the human CRB1 and CRB2 genes are responsible of retinal dystrophies such as RP48 and inactivation of their murine homologues disrupts the OLM and causes photoreceptor loss49. We thus reasoned that the retinal phenotype of the adult Sfrp1−/− mice could be mechanistically linked to poor Müller/photoreceptor cell adhesion, which, in turn, would be responsible of photoreceptor alterations. This mechanism is based on the notion that SFRP1 acts as a negative modulator of ADAM1012,13,22,25, which proteolytically removes the ectodomains (ectodomain shedding) of a large number membrane proteins8, including cell adhesion molecules such as Cadherins and proto-Cadherins14,50,51, thereby controlling cell-cell interactions8,51. Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that abnormal proteolytical processing of OS components influences photoreceptor degeneration52. Furthermore, different ADAM proteins, including ADAM10, have been found expressed in different retinal layers and cell types, comprising Müller cells53,54. We confirmed this distribution with immunohistochemical analysis of ADAM10 localization. In 3 months-old retinas ADAM10 was specifically found in ganglion cells, in the INL (presumably in Müller glial cells based on position) and in the OLM (Fig. 5a,b). Thus and given that SFRP1 is particularly abundant in the OLM/OS region (Fig. 1c,d), we hypothesized that, in SFRP1 absence, components of the OLM could be proteolyzed more efficiently.

Figure 5.

Proteolysis of OLM and OS proteins is increased in Sfrp1−/− retinas leading to an abnormal protein distribution. a, b) Frontal cryostat sections from 3 months-old wt retinas immunostained with secondary antibodies only (a) or with anti-ADAM10 (b). Sections are counterstained with Hoechst. Note the specific immune signal in the OLM (arrows) and in the INL where Müller glial cells are located (yellow arrows). (c–e) Western blot analysis of N-cadherin, PCDH21 and CRB1 content in total protein extracts from three weeks-old wt, Sfrp1−/− and rd10 retinas, as indicated in the panels. For N-cadherin and PCDH21, membranes were probed with antibodies recognizing the respective C-terminal fragments (CTF). Graphs at the bottom of each panel indicate the rate of CTF proteolysis for N-cadherin (c) and PCDH21 (d), calculated as CTF/FL, or the CRB1 levels (e). Plotted values are normalized to α-tubulin. (f–k) Frontal cryostat sections from 6 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− retinas immunostained with antibodies against N-cadherin, β-catenin, and GS as indicated in the panels. Sections are counterstained with Hoechst. White arrows in g, k indicate the gaps in the OLM. Scale bar calibration in k applies to all panels. Abbreviations: CTF: C-terminal fragment; FL: full length; OLM: outer limiting membrane; ONL: outer nuclear layer.

We therefore tested if an enhanced proteolytical processing of N-cadherin and/or PCDH21 could explain the retinal alterations of Sfrp1−/− mice. To this end, we analysed using Western blot the proportion of proteolyzed versus full-length protein levels of N-cadherin and PCDH21 in wt, Sfrp1−/− and rd10 mice. These mice, carrying a missense mutation in the rod specific Pde6b, are a widely used model of fast photoreceptor degeneration55 and thus appeared useful to assess mechanistic specificity. Proteolytical processing of full-length N-cadherin (135 kD) results in the generation of a C-terminal intracellular peptide of 35 kDa51, whereas the 120 kDa full length PCDH21 is cleaved in two fragments of 95 (N-terminal) and 25 (C-terminal) kDa52. Antibodies against the C-terminal portion of either N-Cadherin or PCDH21 were probed against retinal extracts of 3 weeks-old mice. At this stage, the majority of photoreceptors in rd10 mice are still alive, allowing for comparison. Sfrp1−/− retinal extracts contained an increased proportion of the C-terminal fragments of both N-cadherin and PCDH21 when compared to those detected in wt (Figs. 5c,d; S3, about 2- and 3.5-fold, respectively). N-cadherin but not PCDH21 proteolysis was also observed in rd10 retinas (Figs. 5c,d; S3). Comparable and unprocessed levels of CRB1 were present in the 3 genotypes (Figs. 5e; S3), supporting processing specificity. Furthermore, the signal of immunostaining for N-cadherin and β-catenin -which functionally interacts with cadherins at the adherens junctions56- appeared discontinuous and spread along the Müller glial processes in the Sfrp1−/− retinas (Fig. 5g,i) but as a continuous line in wt retinas (Fig. 5f,h). Staining of Müller glial cells with anti-Glutamine Synthetase (GS) confirmed the discontinuous arrangement of their apical end-feet in the mutants but not in the wt retinas (Fig. 5j,k).

Altogether these data indicate that SFRP1 indirectly regulates photoreceptors/Müller glia interaction, which is, in turn, essential for retinal integrity and optimal function.

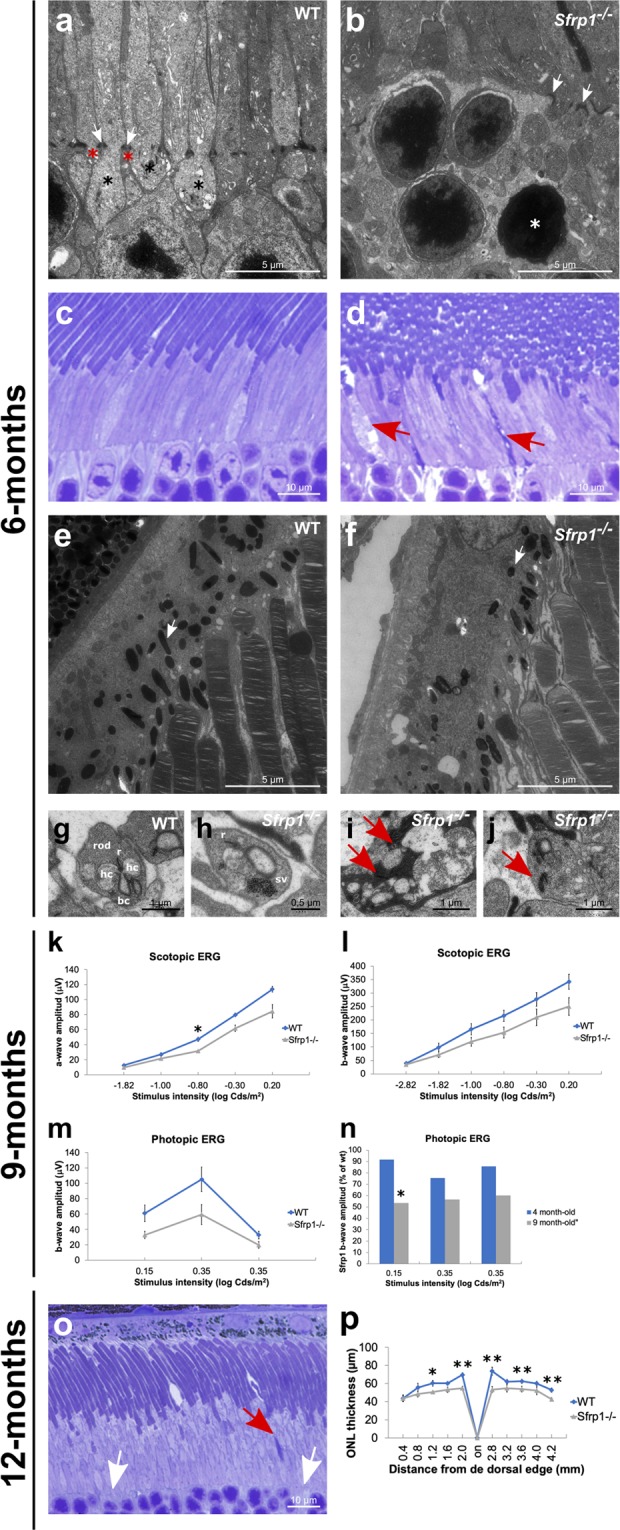

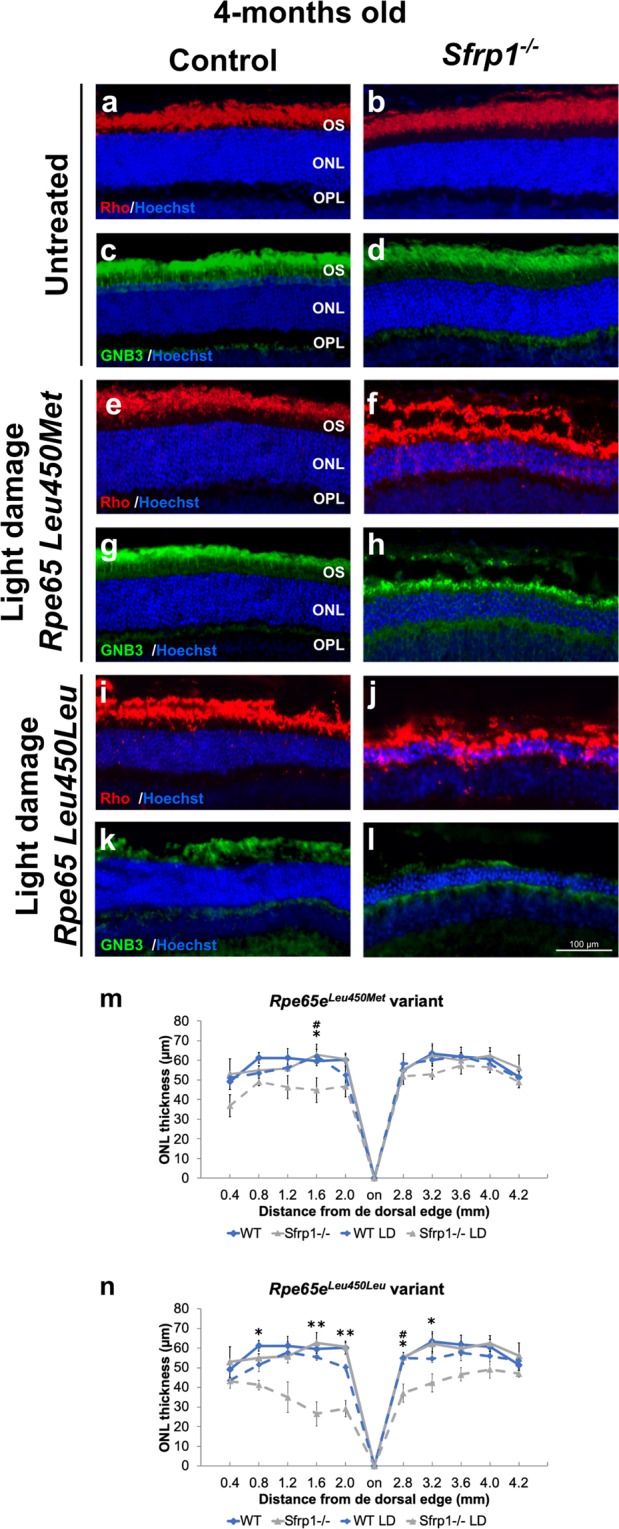

Sfrp1 bestows resistance to the photoreceptors upon light induced damage

If SFRP1 maintains photoreceptor integrity, in its absence photoreceptors should be more sensitive to a neurodegenerative stimulus. Exposure to high intensity light is an experimental paradigm widely used to induce a rhodopsin mediated stereotypic photoreceptor apoptosis29, to which cones are less susceptible57,58. The degree of response however varies according to the pigmentation and genetic background of the animals29. Most prominently, a Leu450Met variation in the RPE-specific Rpe65 gene, found in the C57BL/6 and 129 mouse strains59, confers resistance to light damage. Given the genetic background of the Sfrp1−/− mice, we sequenced the Rpe65 gene in our colony, finding the presence the Rpe65Leu450Met variant mostly in heterozygosis. To clearly separate the contribution of the two alleles we generated Rpe65Leu450Leu;Sfrp1−/− and Rpe65eLeu450Met;Sfrp1−/− animals and their respective controls.

We thereafter exposed 4 months-old wt and Sfrp1−/− mice carrying the two Rpe65 variants to a 15.000 lux light source for 8 h and analysed the extend of photoreceptors’ loss by immunohistochemical analysis 7 days after treatment. Under these conditions and compared to untreated animals (the two Rpe65 variant were undistinguishable), the retinas of Rpe65eLeu450Met;Sfrp+/+ mice were only slightly affected. The morphology and thickness of their ONL as well as the immunolabelling for rod (Rho) and cones (GNB3) markers were comparable to that of untreated animals (Fig. 6a,c,e,g,m). Given the absence of the resistance allele, the photoreceptors of Rpe65eLeu450Leu;Sfrp+/+ mice instead presented signs of disorganization and the ONL was slightly thinner in central regions as compared to untreated mice (Fig. 6a,c,i,k,n). By contrast, the retinas of Rpe65eLeu450Met;Sfrp1−/− and, to a larger extend, those of Rpe65Leu450Leu;Sfrp1−/− mice were visibly affected by light damage. There was a centralhigh to peripherallow loss of both rod and cones photoreceptors with abnormal localisation of Rho in the cell bodies (Fig. 6b,d,f,h,j,l,n). Cone loss appeared proportionally more significant than that of rods in mice carrying the Rpe65Leu450Leu vs the Rpe65eLeu450Met variant (compare Fig. 6f,h with j,l; Kruskal Wallis with post hoc Dunn, p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Sfrp1−/− retinas are more prone to light-induced damage even in the presence of the Rpe65Leu450Met protective variant. (a–l) Frontal cryostat sections from 4 months-old control and Sfrp1−/− retinas carrying the Rpe65Leu450Leu or the protective Rpe65eLeu450Met variants before and 7 days after light induced-damage (light conditions: 15000 lux of cool white fluorescent light for 8 hrs). Sections were immunostained with antibodies against Rho (rods, red) or GNB3 (cones, green) and counterstained with Hoechst. (m,n) The graphs represent the ONL thickness (measures were taken in cryostat frontal sections of the eye at the level of the optic disk) in the different conditions. Kruskal Wallis with post hoc Dunn. *Indicates significant differences between Sfrp1−/− untreated and light-damage mice. #Indicates significant difference between Sfrp1−/− and wt animals exposed to light damage. No significant differences were found between wt untreated and light-damage mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Scale bar in l applies to all panels. Abbreviations: ONL: outer nuclear layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer; OS outer segment.

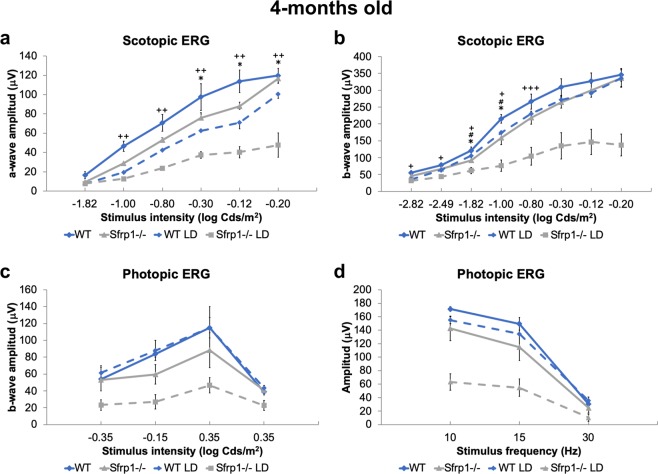

Comparative recording of ERGs responses from Rpe65eLeu450Leu;Sfrp+/+ and Rpe65eLeu450Leu;Sfrp1−/− 4 months-old mice exposed or not to light damage extended this analysis. Untreated mice lacking Sfrp1 presented a slightly reduced rod (scotopic) and cone (photopic) response to light flashes compared to Sfrp1+/+ (Fig. 7a–d). Consistently the reduced loss of photoreceptors observed in Rpe65eLeu450Leu;Sfrp+/+ after damage (Fig. 6i,k), both scotopic and photopic responses were only slightly and non-significantly reduced in these animals (Fig. 7a–d). High intensity light exposure instead strongly reduced the rod and cone response of Rpe65eLeu450Leu;Sfrp1−/− mice (Fig. 7a–d).

Figure 7.

Loss of SFRP1 reduces the ERG response after light-induced damage in the Rpe65Leu450Leu variant. (a,d) The graphs show the a- and b-wave amplitude (µV) of the scotopic (rods and rod bipolar cells, a,b) and photopic (cones and cone bipolar cells, c, d) ERG response from 4 months-old WT and Sfrp1−/− animals to flash light stimuli of increasing brightness (cd/m2). Kruskal Wallis with post hoc Dunn. *indicates significant difference between Sfrp1−/− untreated and light-damage mice. #indicates significant difference between Sfrp1−/− and wt animals exposed to light damage. +Indicates significant differences between Sfrp1−/− and wt untreated mice. No significant differences were found between untreated and light-damage wt mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: ONL: outer nuclear layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer; OS outer segment.

All in all, these data indicate that SFRP1 activity critically supports photoreceptor integrity and function upon a neurodegenerative stimulus.

Discussion

Photoreceptors’ degeneration has devastating consequences on visual perception. So far lost photoreceptors cannot be effectively replaced but, in many cases, restraining their alterations would be sufficient to enable a normal life in affected individuals60. This may be particularly important for cones because they are activated by day-light or artificial illumination and thus enable sufficient vision in current society. The identification of the mechanisms that contributes to the integrity of photoreceptors (cones in particular) may thus help designing protective/therapeutic strategies to guarantee sufficient visual percetion. In this study, we have identified SFRP1 as a component of the machinery that maintains photoreceptors’ organization and integrity, conferring them some protection against light induced damage. Our data point to a mechanism in which SFRP1 would favour the tight cellular adhesions underlying the OLM, which, in turn, is essential for photoreceptors’ function and fitness.

In absence of Sfrp1, cones are the first photoreceptors to show abnormalities with misplaced cell bodies and occasional OS de-compaction detected since young adult stages and light-damage susceptibility. This is somewhat unusual because cones have been shown to be more resistant to this type of damage57. This unusual behaviour might reflect a particular dependence of cones on the interaction with the surround tissues60. Indeed, a number of genes responsible of cone dystrophies encodes proteins involved in cell adhesion4,7,61. Furthermore, overexpression studies in the embryonic chick retina indicate that Sfrp1 promotes cone generation19, although Sfrp1−/− eyes show no developmental defects18,30,31. This may be because the related Sfrp2 and Sfrp5 compensate Sfrp1 function during development12,18,32,62. In the adult mouse retina, Sfrp2 and Sfrp5 mRNAs are absent or poorly expressed (Fig. S1), allowing to uncover a specific SFRP1 activity in the retina. We have observed that the initially subtle cone alterations worsen with time, and are followed by the appearance of rods’ defects and visual function impoverishment. The emergence of these defects have been also observed in aged retinas63,64, in which, according to our data, SFRP1 content is progressively decreasing.

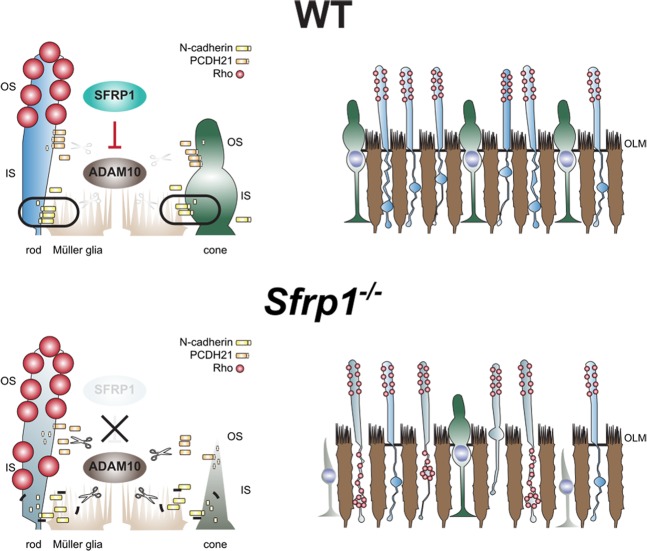

SFRP proteins have been initially discovered and described as apoptosis-related proteins65. We cannot fully discard that retinal SFRP1 may in part have such an activity. However, whereas SFRP2 and SFRP5 have anti-apoptotic functions65,66, SFRP1 over-expression increases cell sensitivity to pro-apoptotic stimuli65, making the defects observed in Sfrp1−/− retina hardly interpretable through an apoptotic mechanism. Inhibition of Wnt signalling, a SFRP1 function observed in many different contexts11, is also unlikely in the adult retina, because photoreceptors are significantly less vulnerable to light-induced damage upon Wnt signalling activation67, which is the opposite of what we observe in Sfrp1−/− mice. The Sfrp1−/− retinal phenotype can instead be best explained considering the inhibitory function that SFRP1 exerts on the metalloprotease ADAM1012,13. In a speculative model (Fig. 8), we envisage that SFRP1, produced by photoreceptors and possibly Müller glial cells, down-regulates ADAM10 activity at the OLM, thereby maintaining the required tight adhesion between the end-feet of Müller cells and the IS of the photoreceptors. In its absence, the increased proteolysis of the OLM and OS components loosen the OLM, progressively impairing photoreceptors’ anchorage. The OLM confers mechanical strength to the retina and limits the diffusion of components of the photo-transduction cascade. Its loosening sets the conditions for loss of photoreceptors’ fitness, making the cells more sensitive to light, and possibly, other types of stress (Fig. 8). This tentative model is supported by the appropriate localization of the required molecular machinery -ADAM10, SFRP1 and different cell adhesion molecules- within the retina44,45,53,54. Indeed, our data shows that both proteins localize in the OLM and regions of the INL compatible with Müller glial cell localization. We have previously shown that SFRP1 physically interacts with ADAM10 in both the retina and the telencephalon12,13, down-modulating the proteolysis of different ADAM10 substrates12,13,22,25. Consistent with this notion, here we have observed an increased shedding of N-cadherin and PCDH21 in the Sfrp1−/− retinas. Increased proteolysis of these molecules seems to weaken cell-cell interactions50,51 and thus may well explain the intermittent breakage of the OLM in the Sfrp1−/− retinas, with the consequent disorganization of the ONL and rhodopsin distribution. The latter defect is considered both a consequence and a further cause of rod degenerative signs, including the decompaction of the OS disc membrane stacks68, as we observed in the Sfrp1−/− mutants.

Figure 8.

Proposed model for the defects observed in the Sfrp1−/− mice. See the discussion for details. Abbreviations: IN: inner segment; OLM: outer limiting membrane; OS: outer segment. (EC author ‘s drawing).

In further support for our findings, missense mutations in PCDH21 have been identified in patients affected by autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy4,61, suggesting that this protocadherin might be particularly relevant for cone survival. Indeed, its targeted disruption in mice causes OS fragmentation followed by a relatively mild decrease of the ERG response and photoreceptors’ loss52, somewhat resembling the Sfrp1−/− retinal phenotype. However, the precise relationship between PCDH21 shedding and photoreceptor degeneration might not be so straightforward. Analysis of PCDH21 shedding in mice that lack peripherin (rds−/−), a structural OS protein, revealed higher levels of protein expression and a decreased proteolysis52 and we show that in rd10 mice PCDH21 proteolysis was similar to wt. The reasons for these differences likely reflect the primary genetic causes of photoreceptors degeneration in rd10 and rds mice: PCDH21 and peripherin have structural functions whereas rd10 mice carry a mutation in a component of the rod phototransduction cascade55. Changes in cell adhesion might thus be a consequence rather a cause in rd10 mice.

Our study highlights a specific role of Sfrp1 in the adult retina. We have interpreted these findings in light of the idea that SFRP1 acts as an endogenous inhibitor of ADAM10 in other contexts12,13,22,25. Our findings however are in apparent contradiction with the observation that in the brain SFRP1 expression increases with aging69 and is upregulated in individual affected by Alzheimer’s disease13, whereas it is barely detectable in the cortex of young and healthy individuals. We believe that this apparent discrepancy is linked to differential distribution of the protein in homeostatic conditions and the drastic alterations that occur during neurodegenerative events. In Alzheimer’s disease, activated glial cells (particularly astrocytes) produce SFRP1, leading to increased levels of toxic products of APP processing13, which further sustain chronic inflammation16. In the adult retina, both neurons and likely Müller glial cells produce SFRP1, which is localized at the OLM with a putative homeostatic function over ADAM10. Its loss of function leads to subtle and slow alterations that are not associated with glial cell reactivity. Drastic photoreceptors’ degeneration, leads instead to neuroinflammation70–72. We expect that in this condition Sfrp1 expression would be also up-regulated in reactive retinal glia, explaining the reported elevated expression and ectopic distribution of SFRP1 in RP24,27. We also expect that neuroinflammatory functions of SFRP116 would override its homeostatic role, although testing whether this is the case is not straightforward. SFRP1 expression is under strong epigenetic regulation28, which may further tune SFRP1 protective or offensive role in the retina.

In conclusion, we show that Sfrp1 contribute to adult retinal homeostasis maintaining the integrity of the OLM. The phenotype observed in Sfrp1 null mice suggest the possibility that the age-related decrease of retinal fitness and visual performance might involve a progressive down-regulation of Sfrp1 expression. Furthermore, differential SFRP1 expression among individuals may represent one of the many possible causes of the low genotype-phenotype correlation observed among individuals suffering of retinal dystrophies.

Methods

Animals

Sfrp1tm1Aksh (Sfrp1−/− mice, thereafter) and Sfrp5tm1Aksh mice were generated as described30,73, were kindly provided by Dr. A. Shimono (TransGenic Inc. Chuo, Kobe, Japan) and maintained in a mixed C57BL/6 ×129 genetic background (B6;129). Mutant mice were compared with wild type (wt) littermates. All animals were housed and bred at the CBMSO animal facility in a 12 h light/dark cycle and treated according to European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC) regulating animal research. All procedures were approved by the Bioethics Subcommittee of Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC, Madrid, Spain) and the Comunidad de Madrid under the following protocol approval number (PROEX 100/15; RD 53/2013).

Genotyping for Rpe65 and Crb1 variants

To determine which are the Crb1 and Rpe65 gene variants present in the genome of the mouse line used in this study, tail genomic DNA was isolated from Sfrp1−/− mice and their wt littermates according to standard protocols and genotyped as described36,59. To determine the sequence of Crb1 and Rpe65 we used the following primer pairs: Crb1 Fw, 5′-GGTGACCAATCTGTTGACAATCC-3′; Rv, 5′-GCCCCATTTG CACACTGATGAC-3′36; Rpe65; Fw, 5′-CTGACAAGCTCTGTAAG-3′; Rv, 5′-CATTACCATCAT CTTCTTCCA-3′36,59. Amplified fragments were sequenced (Secugen S.L., Madrid) and analysed using CLC Sequence Viewer 6 (Qiagen).

In situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IH)

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and perfused intracardially with 4% PFA in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Alternatively, animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and eyes were enucleated and fixed by immersion in 4% PFA in PB for 2 h. The anterior segment of the eye was removed and the eyecups were cryoprotected by equilibration in 15–30% sucrose gradation in PB, embedded in 7.5% gelatine/15% sucrose solution, frozen and sectioned at 16 µm. Sections were processed for in situ hybridization (ISH) as described22 using a DIG-labelled anti-sense riboprobe for Sfrp1, Sfrp2 and Adam10. When processed for immunohistochemistry (IH), the sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature (RT) in a solution containing 1% BSA, 0.1% gelatine and 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. Primary antibodies were the following: rabbit anti-SFRP1(1:500), rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes, 1:1000); rabbit anti-ADAM10 (1:500, Abcam); mouse anti-Rhodopsin K16-155C74 (kindly provided by Dr. P. Hargrave, 1:100), rabbit anti-Guanine Nucleotide Binding protein (G protein Beta 3 subunit, GNB3; Abcam; 1:1000), rabbit anti-β-catenin (Abcam, 1:1000), mouse anti-N-cadherin (Invitrogen; 1:500), mouse anti-Glutamine Synthetase (GS; Millipore, 1:1000). Sections were washed and incubated with the appropriate Alexa-Fluor 488 or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, 1:1000) at RT for 90 min. After washing, the tissue was counterstained with Hoechst (Sigma), mounted in Mowiol and analysed with light (Leica DM500) or confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 710). Confocal images were acquired with identical settings. Figures display representative images. Every staining was performed in a minimum of 3 control and 3 mutant mice, obtaining equivalent results. Retina thickness was measured using Hoechst stained cryostat sections at 400 to 1800 µm from the optic nerve head at intervals of 200 µm. Mean ± SEM thickness was calculated and plotted using Excel software. Mann-Whitney U test was applied for comparison between wt and mutant animals.

ELISA

To quantify the amount of SFRP1 protein, retinas from WT mice were isolated and lysed in RIPA buffer. SFRP1 protein levels were determined using a specific capture ELISA as detailed in13.

Transmission electron microscopy

Eyes were fixed by immersion in 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% PFA in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. Samples were treated with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated and embedded in Epon 812. Semi-thin sections (0.7 μm) were stained with toluidine blue and observed by light microscopy (Leica DM500), whereas ultrathin sections were analysed by electron microscopy (Zeiss EM900). Distributions of cone nuclei were measured in central retina semi-thin sections of 3 wt or mutant mice at (2 or 6 months old) and statistics was calculated and plotted using Excel software. Mann-Whitney U test was applied for comparison between wt and mutant animals. At least 3 wt or mutant mice were analysed using electron microscopy. Figures display representative images.

Western blot analysis

Isolated retinal tissue including the RPE was incubated in 2 mM CaCl2 at room temperature for 30 min and then in buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, complete protease inhibitor cocktail and PMSF (Roche), as previously described52. Total proteins (50 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Membranes were immersed in a solution of 5% non-fat milk and 0.1% Tween 20 in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS) for 2 h and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies used were: rabbit antiserum against the C-terminal domain of PCDH21 (a kind gift of Dr. A. Rattner; 1:10.000), mouse monoclonal antibody generated against the C-terminal domain of N-cadherin (Invitrogen; 1:500); anti-CRB1 (a kind gift of Dr. J. Wijnholds, 1:500), and mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, 1:10.000), used as a loading control. The membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit or mouse antibodies followed by ECL Advanced Western Blotting Detection Kit (Amersham). The immune-reactive bands were quantified by densitometry and the amount of proteolyzed fragment was estimated as the ratio of C-terminal fragment (CTF)/full length (FL)/α-tubulin band values. Western blots were repeated at least 3 times obtaining similar results.

Light-induced retinal damage

The pupils from 4 and 9 months-old mice were dilated by topical administration of 1% tropicamide (Alcón cusí) 30 min before light exposure and by a second administration after the first 4 h of exposure. The light exposure device consisted of cages with reflective interiors, in which freely moving animals were exposed, at the same time of the day, to 15000 lux of cool white fluorescent light for 8 h. Control animals were sacrificed before light exposure, whereas experimental animals were sacrificed 7 days after completed light exposure.

Electroretinography (ERG)

Mice were dark-adapted overnight. All procedures were performed under dim red light following the ISCEV guidelines75. Animals were anesthetized by intra-peritoneal injection of ketamine (95 mg/Kg) and xylazine (5 mg/Kg). The body temperature was maintained with an electric heating pad. The pupils were dilated by topical administration of 1% tropicamide as above. A drop of 2% methylcellulose was then placed between the cornea and the silver electrode to maintain conductivity. VisioSystem Veterinary set up (SIEM Bio-Médicale) was used to deliver flash stimuli, as well as to amplify, filter and analyse photoreceptor responses. Rod responses (Scotopic ERG) were determined using stimulation intensities ranging from −2.8 to −0.2 log Cd s/m2. Cone responses (Photopic ERG) were registered after 10 min adaptation to a 3 Cd/m2 background light using stimulation intensities ranging from −0.35 to 0.35 log Cd s/m2 and after 10 min adaptation to a 30.3 Cd/m2 background light using a stimulation intensity of 0.35 log Cd s/m2. Rods may respond even in photopic conditions76,77. We thus tested cone response also by flicker ERG using different frequencies that allow discriminating cone from rod response. Indeed, rods only respond to low frequency stimuli (5–15 Hz) whereas cones can respond to both low and high frequencies (5–35 Hz)76,77. Flicker ERG was performed with a stimulation intensity of 0.5 log Cd s/m2 at frequencies of 10, 20 and 30 Hz, after 10 min adaptation to a 30.3 Cd/m2 background light. ERGs were recorded in 4 months old mice, 5 wt and 6 mutant mice homozygotes for the protective Rpe65Leu450Met gene variant, in 5 wt and 5 mutant mice heterozygotes for the protective Rpe65Leu450Met gene variant and in 2 wt and 3 mutant mice without protective gene variant. ERGs were also recorded in 9 months old mice, 5 wt and 5 mutant mice homozygotes for the protective Rpe65Leu450Met gene variant. Mean ± SEM values were calculated and plotted using Excel software. Mann-Whitney U test was applied for comparison between wt and mutant mice whereas Kruskal Wallis with post hoc Dunn was applied in the case of light-damaged experiments.

Ethics approval

Animals were housed and treated according to European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC) regulating animal research. All procedures were approved by the Bioethics Subcommittee of Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC, Madrid, Spain) and the Comunidad de Madrid under the following protocol approval number (PROEX 100/15; RD 53/2013).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank O. Herreras (Cajal Institute, CSIC) and E. Martín (Universidad de Albacete) for advice and support in the initial ERG studies. Supported by grants from Fundaluce, Fundación ONCE, Retina España and from the Spanish MINECO (BFU2010-16031; BFU2013-43213-P; BFU2016-75412-R with FEDER support). A CBMSO Institutional grant from the Fundación Ramon Areces is also acknowledged. EC and AS were supported by the CIBERER and JRC and GP are recipient of FPI fellowships (BES-2011-047189; BES-2017-080318). AV is supported by a JAE-Intro fellowship from the CSIC. We also acknowledge support of the publication fee by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).

Author contributions

E.C. and F.M. designed the experiments, performed and analysed experiments and contributed to manuscript preparation. J.R.C. participated in immunohistochemical and E.R.G. studies. C.L. performed and analysed EM studies. G.P., A.V. and R.S. performed ELISA studies. M.J.B. and A.S. genotyped animals and performed biochemical analysis. P.E. participated in experimental design, result discussion and manuscript preparation. P.B. conceived the study, contributed to experimental design and interpretation and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Elsa Cisneros and Fabiana di Marco.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-61970-8.

References

- 1.Letelier J, Bovolenta P, Martinez-Morales JR. The pigmented epithelium, a bright partner against photoreceptor degeneration. J. Neurogenet. 2017;31:203–215. doi: 10.1080/01677063.2017.1395876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wert KJ, Lin JH, Tsang SH. General pathophysiology in retinal degeneration. Dev. Ophthalmol. 2014;53:33–43. doi: 10.1159/000357294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.https://sph.uth.edu/Retnet/.

- 4.Ostergaard E, Batbayli M, Duno M, Vilhelmsen K, Rosenberg T. Mutations in PCDH21 cause autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:665–669. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivolta C, Sharon D, DeAngelis MM, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa and allied diseases: numerous diseases, genes, and inheritance patterns. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1219–1227. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.10.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alves CH, Pellissier LP, Wijnholds J. The CRB1 and adherens junction complex proteins in retinal development and maintenance. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2014;40:35–52. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parry DA, et al. Loss of the metalloprotease ADAM9 leads to cone-rod dystrophy in humans and retinal degeneration in mice. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtenthaler, S.F., Lemberg, M.K. & Fluhrer, R. Proteolytic ectodomain shedding of membrane proteins in mammals-hardware, concepts, and recent developments. EMBO J37 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Oria VO, Lopatta P, Schilling O. The pleiotropic roles of ADAM9 in the biology of solid tumors. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018;75:2291–2301. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2796-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacione LR, Szego MJ, Ikeda S, Nishina PM, McInnes RR. Progress toward understanding the genetic and biochemical mechanisms of inherited photoreceptor degenerations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;26:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bovolenta P, Esteve P, Ruiz JM, Cisneros E, Lopez-Rios J. Beyond Wnt inhibition: new functions of secreted Frizzled-related proteins in development and disease. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:737–746. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteve P, et al. SFRPs act as negative modulators of ADAM10 to regulate retinal neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:562–569. doi: 10.1038/nn.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteve P, et al. Elevated levels of Secreted-Frizzled-Related-Protein 1 contribute to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:1258–1268. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn, P.H. et al. Systematic substrate identification indicates a central role for the metalloprotease ADAM10 in axon targeting and synapse function. Elife5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Saftig P, Lichtenthaler SF. The alpha secretase ADAM10: A metalloprotease with multiple functions in the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015;135:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rueda-Carrasco, J.M. et al. Astrocyte-derived SFRP1 shapes microglial response during neuroinflammation. Submitted (2020).

- 17.Esteve P, Lopez-Rios J, Bovolenta P. SFRP1 is required for the proper establishment of the eye field in the medaka fish. Mechanisms Dev. 2004;121:687–701. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esteve P, et al. Secreted frizzled-related proteins are required for Wnt/beta-catenin signalling activation in the vertebrate optic cup. Dev. 2011;138:4179–4184. doi: 10.1242/dev.065839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteve P, Trousse F, Rodriguez J, Bovolenta P. SFRP1 modulates retina cell differentiation through a beta-catenin-independent mechanism. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2471–2481. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holly VL, Widen SA, Famulski JK, Waskiewicz AJ. Sfrp1a and Sfrp5 function as positive regulators of Wnt and BMP signaling during early retinal development. Dev. Biol. 2014;388:192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez-Rios J, Esteve P, Ruiz JM, Bovolenta P. The Netrin-related domain of Sfrp1 interacts with Wnt ligands and antagonizes their activity in the anterior neural plate. Neural Dev. 2008;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcos S, et al. Secreted frizzled related proteins modulate pathfinding and fasciculation of mouse retina ganglion cell axons by direct and indirect mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:4729–4740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3304-13.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama Y, et al. Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 are not involved in Wnt/beta-catenin signal silencing during lens induction but are required for maintenance of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in lens epithelial cells. Dev. Biol. 2013;384:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones SE, Jomary C, Grist J, Stewart HJ, Neal MJ. Modulated expression of secreted frizzled-related proteins in human retinal degeneration. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3963–3967. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200012180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esteve P, Crespo I, Kaimakis P, Sandonis A, Bovolenta P. Sfrp1 Modulates Cell-signaling Events Underlying Telencephalic Patterning, Growth and Differentiation. Cereb. Cortex. 2019;29:1059–1074. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Hoyos M, et al. Evaluation of SFRP1 as a candidate for human retinal dystrophies. Mol. Vis. 2004;10:426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones SE, Jomary C, Grist J, Stewart HJ, Neal MJ. Altered expression of secreted frizzled-related protein-2 in retinitis pigmentosa retinas. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:1297–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esteve P, Bovolenta P. The advantages and disadvantages of sfrp1 and sfrp2 expression in pathological events. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2010;221:11–17. doi: 10.1620/tjem.221.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenzel A, Grimm C, Samardzija M, Reme CE. Molecular mechanisms of light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis and neuroprotection for retinal degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2005;24:275–306. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satoh W, Gotoh T, Tsunematsu Y, Aizawa S, Shimono A. Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 regulate anteroposterior axis elongation and somite segmentation during mouse embryogenesis. Dev. 2006;133:989–999. doi: 10.1242/dev.02274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trevant B, et al. Expression of secreted frizzled related protein 1, a Wnt antagonist, in brain, kidney, and skeleton is dispensable for normal embryonic development. J. Cell Physiol. 2008;217:113–126. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Wallace VA. Characterization of Wnt signaling components and activation of the Wnt canonical pathway in the murine retina. Dev. Dyn. 2003;227:323–334. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rattner A, et al. A family of secreted proteins contains homology to the cysteine-rich ligand-binding domain of frizzled receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM. Rods and cones in the mouse retina. I. Structural analysis using light and electron microscopy. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979;188:245–262. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mii Y, Taira M. Secreted Frizzled-related proteins enhance the diffusion of Wnt ligands and expand their signalling range. Dev. 2009;136:4083–4088. doi: 10.1242/dev.032524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattapallil MJ, et al. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:2921–2927. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonilha VL. Age and disease-related structural changes in the retinal pigment epithelium. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2008;2:413–424. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolesnikov AV, Fan J, Crouch RK, Kefalov VJ. Age-related deterioration of rod vision in mice. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:11222–11231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4239-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samuel MA, Zhang Y, Meister M, Sanes JR. Age-related alterations in neurons of the mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:16033–16044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3580-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollingsworth TJ, Gross AK. Defective trafficking of rhodopsin and its role in retinal degenerations. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012;293:1–44. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394304-0.00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Omri S, et al. The outer limiting membrane (OLM) revisited: clinical implications. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2010;4:183–195. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishikawa Y, Mine S. Aminoadipic acid toxic effects on retinal glial cells. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 1983;27:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rich KA, Figueroa SL, Zhan Y, Blanks JC. Effects of Muller cell disruption on mouse photoreceptor cell development. Exp. Eye Res. 1995;61:235–248. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(05)80043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsunaga M, Hatta K, Takeichi M. Role of N-cadherin cell adhesion molecules in the histogenesis of neural retina. Neuron. 1988;1:289–295. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rattner A, et al. A photoreceptor-specific cadherin is essential for the structural integrity of the outer segment and for photoreceptor survival. Neuron. 2001;32:775–786. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alves C. Henrique, Boon Nanda, Mulder Aat A., Koster Abraham J., Jost Carolina R., Wijnholds Jan. CRB2 Loss in Rod Photoreceptors Is Associated with Progressive Loss of Retinal Contrast Sensitivity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(17):4069. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West EL, et al. Pharmacological disruption of the outer limiting membrane leads to increased retinal integration of transplanted photoreceptor precursors. Exp. Eye Res. 2008;86:601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richard M, et al. Towards understanding CRUMBS function in retinal dystrophies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R235–243. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quinn PM, et al. Loss of CRB2 in Muller glial cells modifies a CRB1-associated retinitis pigmentosa phenotype into a Leber congenital amaurosis phenotype. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019;28:105–123. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouillot S, et al. Protocadherin-12 cleavage is a regulated process mediated by ADAM10 protein: evidence of shedding up-regulation in pre-eclampsia. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:15195–15204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reiss K, et al. ADAM10 cleavage of N-cadherin and regulation of cell-cell adhesion and beta-catenin nuclear signalling. Embo J. 2005;24:742–752. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rattner A, Chen J, Nathans J. Proteolytic shedding of the extracellular domain of photoreceptor cadherin. Implications for outer segment assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42202–42210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan X, Lin J, Rolfs A, Luo J. Differential expression of the ADAMs in developing chicken retina. Dev. Growth Differ. 2011;53:726–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toonen JA, Ronchetti A, Sidjanin DJ. A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase10 (ADAM10) Regulates NOTCH Signaling during Early Retinal Development. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Won J, et al. Mouse model resources for vision research. J. Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:391384. doi: 10.1155/2011/391384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris TJ, Peifer M. Decisions, decisions: beta-catenin chooses between adhesion and transcription. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okano K, et al. Retinal cone and rod photoreceptor cells exhibit differential susceptibility to light-induced damage. J. Neurochem. 2012;121:146–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samardzija M, et al. Light stress affects cones and horizontal cells via rhodopsin-mediated mechanisms. Exp. Eye Res. 2019;186:107719. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wenzel A, Reme CE, Williams TP, Hafezi F, Grimm C. The Rpe65 Leu450Met variation increases retinal resistance against light-induced degeneration by slowing rhodopsin regeneration. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:53–58. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00053.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bovolenta P, Cisneros E. Retinitis pigmentosa: cone photoreceptors starving to death. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nn0109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henderson RH, et al. Biallelic mutation of protocadherin-21 (PCDH21) causes retinal degeneration in humans. Mol. Vis. 2010;16:46–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang JT, et al. Cloning and characterization of a secreted frizzled-related protein that is expressed by the retinal pigment epithelium. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:575–583. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nadal-Nicolas FM, Vidal-Sanz M, Agudo-Barriuso M. The senescent vision: dysfunction or neuronal loss? Aging. 2018;11:15–17. doi: 10.18632/aging.101734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salvi SM, Akhtar S, Currie Z. Ageing changes in the eye. Postgrad. Med. J. 2006;82:581–587. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.040857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melkonyan HS, et al. SARPs: a family of secreted apoptosis-related proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13636–13641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz JM, Rodriguez J, Bovolenta P. Growth and differentiation of the retina and the optic tectum in the medaka fish requires olSfrp5. Dev. Neurobiol. 2009;69:617–632. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Braunger BM, et al. Constitutive overexpression of Norrin activates Wnt/beta-catenin and endothelin-2 signaling to protect photoreceptors from light damage. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013;50:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao J, et al. Progressive photoreceptor degeneration, outer segment dysplasia, and rhodopsin mislocalization in mice with targeted disruption of the retinitis pigmentosa-1 (Rp1) gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5698–5703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042122399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Folke J, Pakkenberg B, Brudek T. Impaired Wnt Signaling in the Prefrontal Cortex of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019;56:873–891. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng B, et al. Suppression of microglial activation is neuroprotective in a mouse model of human retinitis pigmentosa. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:8139–8150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5200-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ronning KE, Karlen SJ, Miller EB, Burns ME. Molecular profiling of resident and infiltrating mononuclear phagocytes during rapid adult retinal degeneration using single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4858. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rutar M, Natoli R, Chia RX, Valter K, Provis JM. Chemokine-mediated inflammation in the degenerating retina is coordinated by Muller cells, activated microglia, and retinal pigment epithelium. J. Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:8. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0224-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Satoh W, Matsuyama M, Takemura H, Aizawa S, Shimono A. Sfrp1, Sfrp2, and Sfrp5 regulate the Wnt/beta-catenin and the planar cell polarity pathways during early trunk formation in mouse. Genes. 2008;46:92–103. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adamus G, et al. Anti-rhodopsin monoclonal antibodies of defined specificity: characterization and application. Vis. Res. 1991;31:17–31. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90069-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Robson AG, et al. ISCEV guide to visual electrodiagnostic procedures. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2018;136:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10633-017-9621-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dai X, et al. The frequency-response electroretinogram distinguishes cone and abnormal rod function in rd12 mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rubin GR, Kraft TW. Flicker assessment of rod and cone function in a model of retinal degeneration. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2007;115:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s10633-007-9066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article