Significance

HIF-1 and CITED2 bind TAZ1 with similar affinity but different binding posture. CITED2 is an efficient competitor of HIF-1 and acts as a negative feedback regulator that attenuates HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Here we clarified the underlying mechanisms and the detailed processes of the competition and displacement between HIF-1 and CITED2, which is important for exploring “hypersensitive regulatory switch” in the cell. We show the dominant position of forming TAZ1–CITED2 complex from both thermodynamics and kinetics, in good agreement with experimental results. Main binding states can be recognized from the free energy landscape and the binding status of the conventional LPQ/EL motif. Switching between the bound LPQL and LPEL motifs is the crucial step of displacement between HIF-1 and CITED2.

Keywords: intrinsically disordered proteins, competitive binding, energy landscape, molecular dynamics

Abstract

The TAZ1 domain of CREB binding protein is crucial for transcriptional regulation and recognizes multiple targets. The interactions between TAZ1 and its specific targets are related to the cellular hypoxic negative feedback regulation. Previous experiments reported that one of the TAZ1 targets, CITED2, is an efficient competitor of another target, HIF-1. Here, by developing the structure-based models of TAZ1 complexes, we have uncovered the underlying mechanisms of the competitions between the two intrinsic disordered proteins (IDPs) HIF-1 and CITED2 binding to TAZ1. Our results support the experimental hypothesis on the competition mechanisms and the apparent affinity. Furthermore, the simulations locate the dominant position of forming TAZ1–CITED2 complex in both thermodynamics and kinetics. For thermodynamics, TAZ1–CITED2 is the lowest basin located on the free energy surface of binding in the ternary system. For kinetics, the results suggest that CITED2 binds to TAZ1 faster than HIF-1. In addition, the analysis of contact map and values is important for guiding further experimental studies to understand the biomolecular functions of IDPs.

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) (1–3) behave as disordered/unstructured forms at physiological conditions in isolated states, but sometimes undergo conformational changes to folded form upon binding to the partners (4, 5). Such a binding–coupled–folding scenario has significantly refreshed our understanding of the protein structure–function paradigm. Generally, IDPs are widely involved in many critical physiological processes, such as transcription and translation regulation, cellular signal transduction, protein phosphorylation, and molecular assembles (6, 7).

The transcriptional adaptor zinc-binding 1 (TAZ1) is a domain of CREB binding protein (CBP), which mediates interactions with a series of IDPs and plays an important role in the transcriptional regulation (8). One of its binding partners, the -subunit of the transcription factor (hypoxia inducible factor) HIF-1 (HIF-1), can interact with TAZ1 through its intrinsically disordered C-terminal transactivation domain under hypoxia conditions while it is hydroxylated under normoxic conditions (9–13). The interactions between TAZ1 and HIF-1 are related to the transcriptional regulation of genes that are crucial for cell survival (10, 11, 14). Another binding partner, CITED2, expression of which is directly induced by HIF-1, competes for TAZ1 binding with HIF-1 through its own disordered transactivation domain, inhibits the activity of the HIF-1, and thereby attenuates the cellular response to low tissue oxygen concentration (9, 15–17). CITED2 acts as a negative feedback regulator of HIF-1 and occupies a different but partially overlapped binding site from that of HIF-1. Intriguingly, both of the two ligands of TAZ1, HIF-1 and CITED2, have a conserved LP(Q/E)L region (LPQL in HIF-1; LPEL in CITED2) that is essential for negative feedback regulation (10, 11, 15, 16). These LPQL and LPEL domains bind with the same place on the TAZ1 surface at bound state (Fig. 1).

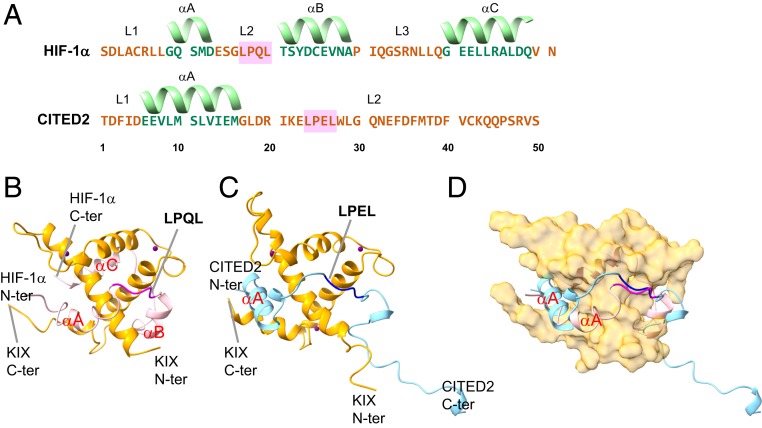

Fig. 1.

The sequences (A) and binding postures (B–D) of HIF-1 (51 a.a., corresponding to 776 to 826 in 1L8C) and CITED2 (50 a.a., corresponding to 220 to 269 in 1R8U). HIF-1 includes three main alpha helices, A (783 to 788), B (796 to 804), and C (815 to 824), and three main loop regions, L1 (776 to 782), L2 (789 to 795), and L3 (805 to 814). LPQL motif (792 to 795) is included in the L2 region. CITED2 has only one helix, A (225 to 235), and two main loop regions, L1 (220 to 224) and L2 (236 to 269). LPEL motif (243 to 246) is included in the L2 region. The complex structures (TAZ1–HIF-1 in B, TAZ1–CITED2 in C) are extracted from the NMR structures 1L8C and 1R8U. Their superimposed structure is illustrated in D. A, LPQL of HIF-1, and , LPEL of CITED2, share the same binding surface of TAZ1. The alpha helices of HIF-1 and CITED2 are labeled both in the sequences and in the complex figures. The essential conserved motifs are emphasized with pink boxes (in the sequences) and with magenta and dark blue cartoons (in the complex figures).

This competition between HIF-1 and CITED2 can be considered as a “hypersensitive regulatory switch” which is dependent on the folding and binding properties of these IDPs and probably exemplifies a common strategy used by the cell to respond rapidly to environmental signals (17). Understanding the underlying mechanism of the competitive binding between HIF-1 and CITED2 will be crucial for studying the protein switches in cell. Although the structures of both TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complexes have been deposited to Protein Data Bank (PDB) (10, 15), little is known about how binding affinity or binding mechanism will be influenced if two ligands coexist. Both HIF-1 and CITED2 bind to TAZ1 with the same high affinity ( nM) (17). In addition, HIF-1 and CITED2 utilize partially overlapped binding sites to form complexes with TAZ1 (10, 11, 15, 16), suggesting that HIF-1 and CITED2 are binding competitors to TAZ1. In 2017, the NMR experiments of Wright et al. (17) observed that TAZ1–CITED2 complex is dominant in the TAZ1:HIF-1:CITED2 solvation with 1:1:1 molar ratio. Although HIF-1 and CITED2 cannot bind to TAZ1 simultaneously, they suggest the formation of a transient ternary complex when CITED2 displaces HIF-1 by occupying the LPQ/EL site. The fluorescence anisotropy competition experiments found that CITED2 exhibits an apparent of 0.2 0.1 nM to TAZ1–HIF-1 complex, while HIF-1 displaces TAZ1-bound CITED2 with a much higher apparent (0.9 0.1 M) (17). These experimental results indicate that CITED2 is extremely effective in displacing HIF-1 from the TAZ1–HIF-1 complex.

The possible mechanism for displacement of HIF-1 from its complex with TAZ1 by CITED2 (17) was proposed to be that CITED2 binds to TAZ1–HIF-1 complex through its N-terminal region, displacing the dynamical and weakly interacting helix of HIF-1, then competing through an intramolecular process for binding to the LP(Q/E)L site. However, it is challenging to prove such a replacing mechanism experimentally. Although molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a good way to investigate the protein systems and give atomic structural information, it is still extremely time-consuming to discover the whole binding/folding mechanism with large conformational changes for conventional MD approaches (18, 19). Recently, the structure-based model (SBM) with two-basin (20–22)/multibasin (23–26) has been developed and successfully applied for the systems with large conformational changes. In our previous work, we have explored the complex association processes and uncovered the binding and folding mechanism as well as the key interactions with SBM and MD simulations (20, 22, 25–29). Here in this study, we developed the binary models of both TAZ1–HIF-1 binding and TAZ1–CITED2 binding as well as the ternary model of TAZ1–HIF-1–CITED2 binding to unveil the mechanism of the replacing processes (including HIF-1 replacing the TAZ1-bound CITED2 as well as CITED2 replacing the TAZ1-bound HIF-1). Our studies quantified the free energy surface of the overall competition processes and further suggest that it is easier to form TAZ1–CITED2 complex than TAZ1–HIF-1 complex in thermodynamics or kinetics, in line with the experimental findings. This study has potential implications for the underlying details and mechanisms of transcription regulations by TAZ1.

Results and Discussion

Binding Free Energy Surface of the Binary Association Processes.

We used a weighted SBM of TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complexes according to the NMR structures 1L8C (10) and 1R8U (15), respectively. The contact map of the weighted SBM was collected based on the 20 configurations in the PDB, taking into account the NMR structural flexibility. The parameters of the model were calibrated carefully in order to be consistent with the experimental measurements. In detail, the strengths of intrachain interactions of HIF-1 and CITED2 were tuned according to the experimental helical content at unbound state. It was reported that both HIF-1 (776 to 826) and CITED2 (220 to 269) behaved as a random coil at unbound state (10, 15); thus the helical contents of isolated HIF-1 and CITED2 were set to be below 10% in our simulations. Then the strengths of interchain interactions between TAZ1 and HIF-1 as well as between TAZ1 and CITED2 were adapted according to the experimental dissociation constant [ of about 10 nM for both TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 (17)]. In our binary model (TAZ1 binding with one ligand protein), both TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complexes have similar affinities with the experiments (corresponding to about −6.15 and −6.05 kT binding free energies, respectively). The experimental and the simulated of the single ligand binding to TAZ1 (binary system) process are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The experimental (as well as apparent ), the simulated binding energy (the energy difference between the final bound state and the initial unbound state, ) of the different systems

| Process | UB to HB | UB to CB |

| Binary system | ||

| Experimental (nM) | 10 | 10 |

| Simulated (nM) | 8.35 | 10.2 |

| Simulated (kT) | –6.15 | –6.05 |

| Ternary system | ||

| Experimental apparent (nM) | 900 | 0.2 |

| Simulated (nM) | 40.5 | 0.0118 |

| Simulated G (kT) | –5.36 | –9.43 |

The experimental Kd values are extracted from the ref. 17. Note that the experimental apparent Kd are not equal to the simulated Kd due to the difference in the methods for calculating Kd. The method of obtaining the simulated Kd is described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

After performing replica exchange MD (REMD) simulations for sufficient sampling with 28 replicas ranging from about 0.52 to 1.86 (simulation temperature in reduced unit; room/experimental temperature is about 1.04) on both TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complexes, The weighted histogram analysis method algorithm (30, 31) was applied to the REMD trajectories to collect statistics and to obtain the free energy distributions as well as other characteristics at the experimental temperature. Firstly, the binding free energy profile was quantified by projecting the free energy onto the fraction of intermolecular native contacts (), which can be considered as the reaction coordinate of binding. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1, TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 have similar binding affinity (), which agrees with the experimental measured . However, the binding barrier (the energy difference between the unbound state and the transition state (TS), ) of TAZ1–HIF-1 is significantly higher than that of TAZ1–CITED2 ( [TAZ1–HIF-1] is about two times [TAZ1–CITED2]). The thermodynamic results suggest that, when binding to TAZ1, the kinetic binding rate of HIF-1 should be lower than that of CITED2, although the similar binding stabilities are established.

IDPs are typically enriched in charged residues. Previous studies have indicated that the nonnative electrostatic interactions between IDP and the target protein can act as a “steering force” for binding, and increasing these nonnative electrostatic interactions can accelerate the binding rate (29). Moreover, it has been suggested that the distribution of the oppositely charged residues can influence the folding (32) and the assembling properties of IDPs in liquid droplet (33). Here in this study, HIF-1 is −5 charged with eight negative charged residues and three positive charged residues; CITED2 is −7, charged with 11 negative charged residues and four positive charged residues. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S2, CITED2 is charge-concentrated and HIF-1 is a bit charge-scrambled. For CITED2 sequence, N terminus and A helix only have negative charged and neutral residues. At TS, most nonnative electrostatic interactions are located in this region (see the analysis of contact map below; see Fig. 5). As a result, the differences in both number and distributions of the charged residues in HIF-1 and CITED2 may lead to the different binding barriers/rates.

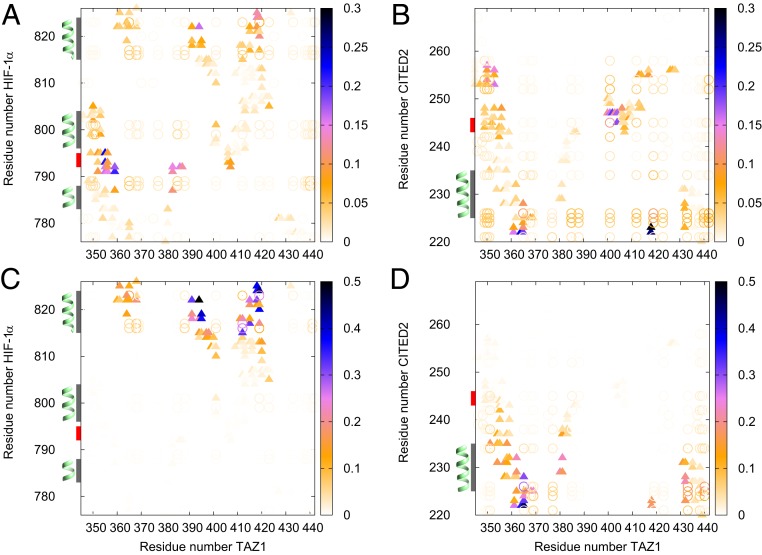

Fig. 5.

The probability of the interactions between TAZ1 (residues 345 to 439, as well as three ) and HIF-1 (residues 776 to 826) or between TAZ1 and CITED2 (residues 220 to 269) at the TS of the binding process () in the binary system, UH (A) and UC (B) processes, as well as at the same binding place in the ternary system, CIH (C) and HIC (D) pathways. helices of HIF-1 and CITED2 sequences are colored in gray, and LPQL/LPEL motif is colored in red, on the y axis. Native contacts are shown as triangles, and nonnative electrostatic interactions are shown as circles. For nonnative electrostatic contacts, a contact is considered formed if the distance between the two residues with opposite charge is lower than 10.0 Å.

The flexible binding or binding–coupled–folding behavior can be illustrated by the free energy surface along , and along , helical content (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). is the fraction of intramolecular native contacts, which acts as folding reaction coordinates. Upon binding, and the helical content of HIF-1 change from 0.30 to 0.75 and 0 to 35% (bottom of the basins of unbound and bound states), respectively. But the changes of the and helical content of CITED2 during binding are not as remarkably large as that of HIF-1; they alter from 0.24 to 0.42 and from 0 to 17%, respectively. In addition, it is obvious that, at the TSs, the and helical content of HIF-1 or CITED2 are similar to that at the unbound state, but are different from that at the bound state. This accords with the induced-fit binding mechanism.

We can study the allosteric effect on TAZ1 between the HIF-1 bound state and the CITED2 bound state. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4, binding of different ligands on TAZ1 can influence the flexibility of C terminus of 1, 2, and 3, as well as the loop regions of TAZ1. These results suggest the role of allosteric regulation in the conformation of TAZ1 during the replacing process of different ligands, which is consistent with the findings in ref. 17.

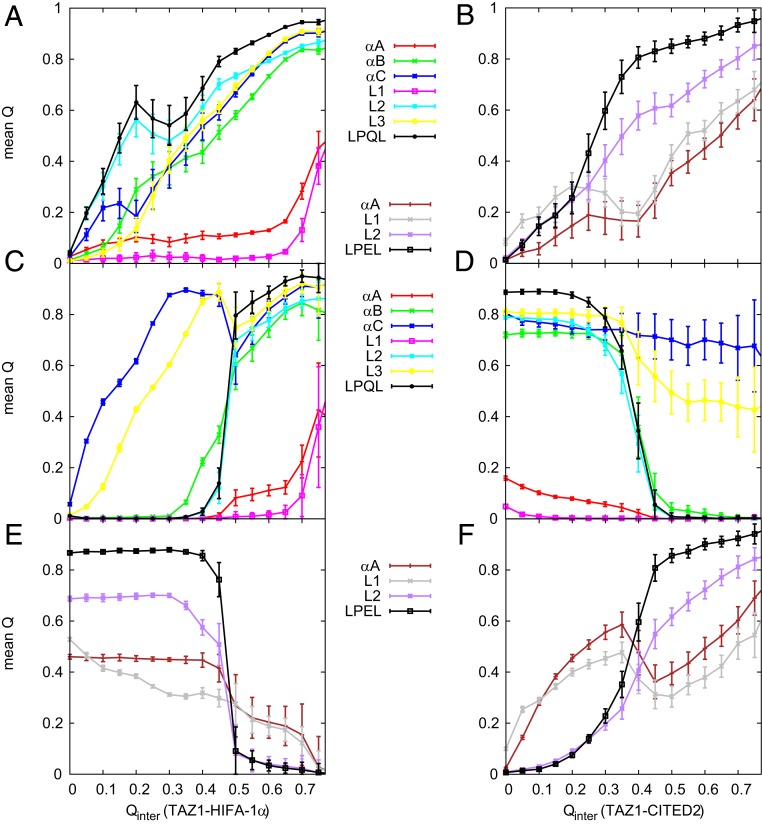

Thermodynamic Mechanism of Ternary TAZ1–HIF-1–CITED2 Complex.

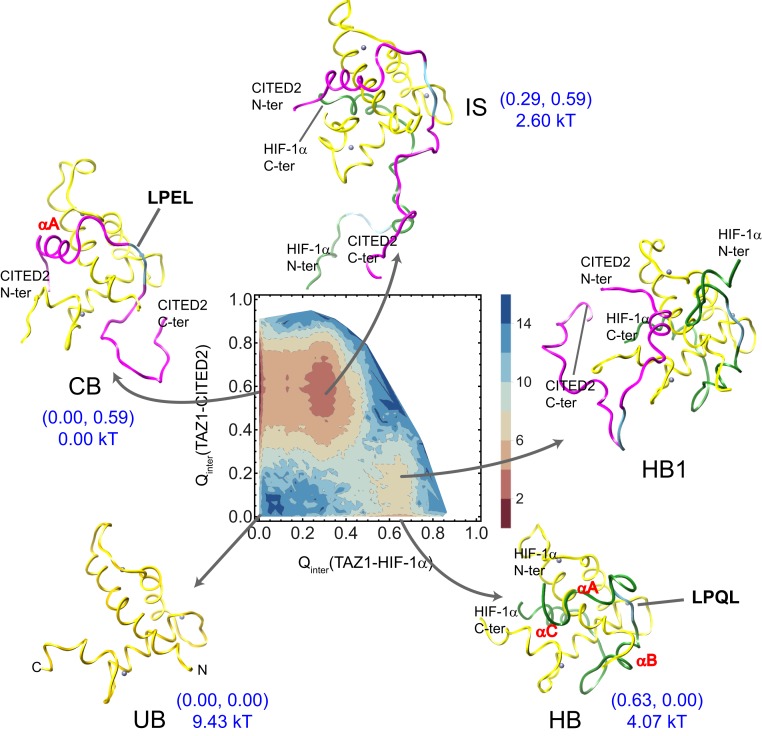

After obtaining the tuned TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 models, we constructed the ternary TAZ1–HIF-1–CITED2 model by putting HIF-1 and CITED2 together with TAZ1 into the same simulation sphere. REMD simulations with 28 replicas ranging from 0.52 to 1.86 temperature (in reduced unit) were performed on ternary TAZ1–HIF-1–CITED2 complex, with both HIF-1 and CITED2 unbound as the initial state. Firstly, the free energy at experimental temperature was obtained and projected on the binding reaction coordinates of both TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 ( [TAZ1–HIF-1] and [TAZ1–CITED2]). As shown in Fig. 2, three main lower basins and other smaller basins can be recognized on the free energy landscape at experimental temperature. The lowest basin corresponds to CITED2 bound state (CB state, 0.00 kT), which indicates that TAZ1–CITED2 is the dominant state of all. This is consistent with the NMR results of ref. 17. HIF-1 bound basin (HB state) is about 4.07 kT higher than CB state, which is another bound state. Because the LPQL region of HIF-1 and the LPEL region of CITED2 share the same binding site on the surface of TAZ1, HIF-1 and CITED2 cannot fully bind with TAZ1 at the same time. The IS state (intermediate state), with HIF-1 partly bound and LPEL of CITED2 occupying the binding site, is the main intermediate state between HB and CB states and is about 2.60 kT less stable than the CB state. The C helix and C terminus of HIF-1 bind with one side of TAZ1, while A helix and LPEL motif of CITED2 bind with the other side of TAZ1 at the IS state. The other states, including the both unbound state (UB state, about 9.43 kT higher than CB state) and the HB1 state near HB state (with part of HIF-1 bound, more than 6 kT higher than CB state), have much higher free energy values than the CB state. The HB1 state has a few configurations with similar free energy values and with A of CITED2 bound ( [TAZ1–HIF-1] being about 0.63 and [TAZ1–CITED2] being about 0.2). Unlike IS state, the HB1 has LPQL bound in the binding site, while LPEL is not bound.

Fig. 2.

The free energy surface at experimental temperature as a function of (TAZ1–HIF-1) and (TAZ1–CITED2) in the ternary system, as well as the main states on the free energy surface (HB1 is not a basin on free energy surface but is an area near HB state with part of CITED2 bound). The values of the reaction coordinates (two values) as well as the free energy at these main states are labeled in this figure. TAZ1 is shown in yellow ribbons (the bound ions are shown with purple spheres), HIF-1 is shown in green ribbons, and CITED2 is shown in magenta ribbons. The LPQL and LPEL motifs are colored in blue. The free energy unit is kT (k is Boltzmann constant).

These states found on the free energy surface of TAZ1 complexed with HIF-1 and CITED2 are consistent with that proposed in the schematic mechanism for displacement of HIF-1 from its complex with TAZ1 by CITED2 (17). Experimentally, Berlow et al. (17) designed a truncated HIF-1 peptide (796 to 826) in the absence of the A region and LPQL motif as well as a truncated CITED2 peptide (216 to 242) in the absence of the LPEL motif. They subsequently performed the NMR experiments. The binding of this truncated CITED2 to the preformed TAZ1–HIF-1 complex was relatively weak, and the affinity of the truncated HIF-1 and the preformed TAZ1–CITED2 complex was even weaker. Therefore, they proposed a hypothetical model of the replacing process between TAZ1-bound HIF-1 and TAZ1-bound CITED2. That is CITED2 binding to TAZ1–HIF-1 through its N-terminal region, displacing the A helix of HIF-1, then competing through an intramolecular process for binding to the LP(Q/E)L site. Here we confirmed this mechanism from MD simulations. This further provides comprehensive understanding of the replacing process of HIF-1 by CITED2, which can be divided into three steps (Fig. 2). In the first step, A helix of CITED2 anchors TAZ1 while only N terminus and A helix of HIF-1 begin to unbind (from HB state to HB1 state); then the LPEL motif of CITED2 initiates the occupancy of the LP(Q/E)L site of TAZ1 and HIF-1 binds to TAZ1 only with the C helix (from HB1 state to IS state); C helix of HIF-1 unbinds from TAZ1 completely in the last step. The second step, where LPEL motif replaces the prebound LPQL motif, is the rate-limited step of the whole process. Beyond the consistency between experiments and simulations, we, interestingly, observed some appealing evidence which is critical in complementing the replacing mechanism to experimental hypothesis. In our model, when the N-terminal A and LPEL motif of CITED2 occupy the binding site of TAZ1–HIF-1 complex, only C-terminal C helix of HIF-1 binds with TAZ1 (as shown in Fig. 2, the IS state). In Berlow’s model, B helix of HIF-1 still binds with TAZ1 at this state. This may be due to the truncated HIF-1 being with B and C, instead of being only with C as designed by the experiments. Including B helix in the truncated HIF-1 may decrease the affinity between truncated HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complex.

In addition, it is worth noting that, although TAZ1–HIF-1 complex and TAZ1–CITED2 complex have similar binding affinity of the binary system in both experiment and theory, the TAZ1–HIF-1 state (HB) and TAZ1–CITED2 state (CB) have different free energy values in the ternary system. The free energy results suggest that CITED2 has more opportunity to bind to TAZ1 than does HIF-1 in the ternary system (Table 1). The binding barrier data discussed above (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) indicate that the binding rate of CITED2 associated with TAZ1 is higher than that of HIF-1 associated with TAZ1, suggesting that CITED2 may bind to TAZ1 before HIF-1 in the ternary system. Moreover, in the ternary system, the binding free energy of HIF-1 in the ternary system (−5.36 kT; Table 1) is higher than that in the binary system (−6.15 kT); the binding free energy of CITED2 in the ternary system (−9.43 kT) is lower than that in the binary system (−6.05 kT). These results suggest that the binding affinity of CITED2 to TAZ1 is much higher than that of HIF-1 to TAZ1 in the ternary system. The ratio of TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 (about 3,432-fold) in simulation is similar to that of the apparent TAZ1–HIF-1 and the apparent TAZ1–CITED2 (4,500-fold) inferred in the experiments (Table 1; it should be noted that the simulated is not equal to the experimental apparent because of the different calculating method). As we all know, the affinity is influenced by both binding (on) rate and unbinding (off) rate. In the ternary system, the binding barriers of HIF-1 and CITED2 (about 1 kT to 2 kT) are similar to those in the binary system. However, the unbinding barrier of CITED2 in the ternary system is around 10 kT, which is about 3 kT higher than that in the binary system. The unbinding barrier of HIF-1 in the ternary system is similar to that in the binary system. Consequently, the unbinding step plays a dominant role in determining the main state of the ternary system.

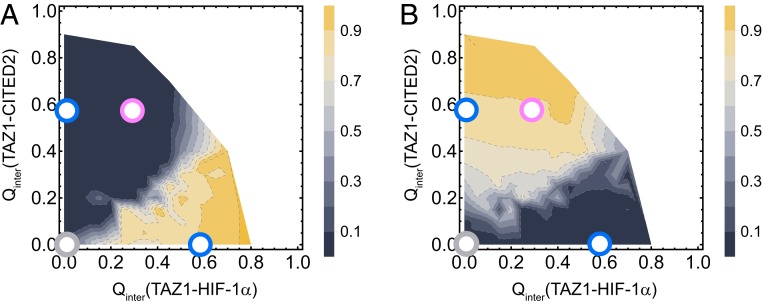

We then calculated the distribution of the helical content and on both binding coordinates in order to show the conformational changes of HIF-1 and CITED2 during binding. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5, HB and HB1 states have similar (HIF-1) and helical content of HIF-1, which is much higher than that of CB and IS states. Likewise, the (CITED2) and helical content of CITED2 decrease from CB and IS states to the HB and HB1 states. Similar behavior can also be found in LPQL and LPEL motifs. As shown in Fig. 3, LPQL/LPEL leaves the binding site when the other ligand almost fully binds to TAZ1. In the direct binding process (from UB to HB/CB state), LPQL/LPEL occupies the binding site during the early part of the binding process (after TS). In the replacement process (from CB to HB or from HB to CB state via IS state), the switch of LPQL and LPEL motifs occurs between the IS state and the HB state. Therefore, the bound of LPQL or LPEL motifs represents the location of the TS (or rate-limited step). We can simply distinguish the four main states by using the LPQL or LPEL motifs. This suggests that the LPQL/LPEL motif is important for binding or replacing processes of TAZ1.

Fig. 3.

Mean between TAZ1 and LPQL of HIF-1 (A) and between TAZ1 and LPEL of CITED2 (B) as a function of (TAZ1–HIF-1) and (TAZ1–CITED2) in the ternary system. The locations of UB, single-ligand-bound (HB or CB), and IS states are shown as gray, blue, and pink circles, respectively.

Kinetics of Different Binding/Replacing Pathways.

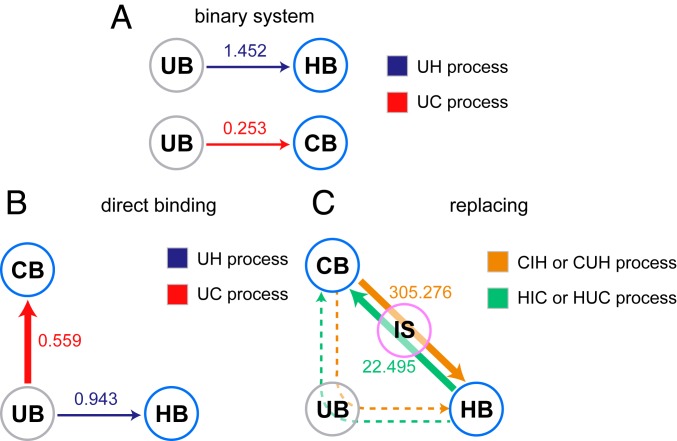

In the binary system, HIF-1 and CITED2 can bind to TAZ1 separately (from UB to HB [UH] or from UB to CB [UC]; Fig. 4A). As shown in the free energy profile in Fig. 2, there are four main states (UB, HB, CB, and IS) in the ternary binding system. From the UB state, TAZ1 can bind to HIF-1 or CITED2 to reach HB or CB state via the direct binding process (UH or UC; Fig. 4B). HIF-1 can replace the TAZ1-bound CITED2 to reach HB state via IS state or UB state (CIH or CUH replacing process). On the other hand, CITED2 can replace the TAZ1-bound HIF-1 to reach CB state via IS state or UB state (HIC or HUC replacing process; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Binding processes in the binary system (A) as well as direct binding (starting from UB state) (B) and replacing (starting from HB or CB state) (C) processes in the ternary system. The probability of each binding or replacing process in the ternary system (B and C) is illustrated with the width of the arrow. The binding time (mean , in units of ) of each process is labeled on the arrow. Note that this simulation binding time is not equal but is expected to be correlated to the real time due to the usage of the coarse-grained model at the residue level in this study.

Aiming to explore the details in the binding processes of the two ligands to TAZ1, we performed kinetic simulations with different initial states at the experimental temperature. Firstly, for the binding processes in the binary system, the binding time of HIF-1 (1.452 ) is much higher than that of CITED2 (0.253 ). In the ternary system, the existence of the second ligand can accelerate the binding of HIF-1 but slow down the binding rate of CITED2 (Fig. 4B). CITED2 still binds to TAZ1 faster than does HIF-1, which is consistent with the analyses above. Aiming to obtain the binding probability for the two different ligands, 200 individual kinetic simulations started with varying both unbound (both HIF-1 and CITED2 isolated in one sphere) configurations were performed. This ternary system reaches CB state first (UB to CB state, denoted as UC pathway) in 173 of the 200 runs, and reaches HB state first (UB to HB state, denoted as UH pathway) in the other 27 of the 200 runs.

We then investigated the replacing process in the ternary system. Two hundred kinetic runs started with varying TAZ1–CITED2 configurations (CB state) and 200 kinetic runs started with varying TAZ1–HIF-1 configurations (HB state) were performed. The mean (mean first passage time of binding, binding time) of the replacement of CITED2 by HIF-1 is 305.276 , which is much higher than that of the replacement of HIF-1 by CITED2 (22.495 , as listed in Table 2). There are two different pathways of the replacing process; one is via the IS state (denoted as CIH or HIC pathway), and the other is via the UB state (denoted as CUH or HUC pathway). The kinetic results suggest that none of these runs pass through the UB state (CUH or HUC; dashed lines in Fig. 4C), which means that the pathways via the IS state (CIH/HIC) are more favorable than those via the UB state (CUH/HUC). Moreover, an exceptionally longer time (nearly 100-fold) is required for the process of replacement (CIH/CUH or HIC/HUC) than for the direct binding process (UH or UC), because the exiting process of the first binding ligand is time-consuming. The barrier of the exiting process of the first binding ligand in CIH or HIC process is about 4 kT to 8 kT, which is much higher than that of the direct binding process (UH or UC, about 1 kT to 2 kT). We have mentioned above that the rate-limited step of replacing process is the switch of LPQL/LPEL motif. As a result, the rate-limited step corresponds to the step from HB to IS in the HIC pathway and the step from IS to HB in the CIH pathway.

Table 2.

Kinetic binding time (mean first passage time of binding, mean , in units of ) of different binding processes

| mean | ||

| Process | UB to HB | UB to CB |

| Binary system | ||

| Binding | 1.452 | 0.253 |

| Ternary system | ||

| Direct binding | 0.943 | 0.559 |

| Replacing | 305.276 | 22.495 |

Two hundred kinetic runs were performed with each starting state (UB, HB, or CB). Note that this is the binding time from the simulations, which is not equal to but expected to be correlated to the real time due to the usage of the coarse-grained model at the residue level in this study.

The contact maps between TAZ1 and HIF-1 and between TAZ1 and CITED2 at the TS of the binding processes in the binary system as well as at the same binding place (with the same ) in the ternary system are illustrated in Fig. 5 to show which part is important for the initial binding process. Because there are no runs via CUH and HUC pathways in our simulations, here, for the ternary system, we analyze the interchain contact maps of CIH and HIC (replacing) pathways. As shown in Fig. 5 A and B, in the binary system, LPQL motif (residues 792 to 795 in 1L8C, highlighted in red in Fig. 5 A and C) and C terminus of HIF-1 have strong interactions with TAZ1; N terminus and LPEL motif (residues 243 to 246 in 1R8U, highlighted in red in Fig. 5 B and D) of CITED2 are crucial for the initial binding to TAZ1. Additionally, there are abundant nonnative electrostatic interactions formed in TSs, implying that TS is highly nonspecific. In contrast, at the same binding place of the ternary system (Fig. 5 C and D), only C terminus of HIF-1 and N terminus of CITED2 are important for the TS. The interactions between LPQL/LPEL motif and TAZ1 are relatively weak or vanish. And the nonnative electrostatic interactions are highly oriented. Therefore, the LPQL/LPEL motif may take different roles in the direct binding and replacing pathways.

Binding Order and Value Analysis.

We then divided HIF-1 and CITED2 into several parts for analysis (illustrated in Fig. 1) and calculated the evolution of the interactions between these parts and TAZ1 in different pathways. As shown in Fig. 6, different pathways have different interacting regions and orders. In the binary system, for HIF-1 binding, the L2 region (including LPQL motif) and C helix reach TAZ1 first (Fig. 6A), followed by the B helix and L3 region. The N-terminal A helix and L1 regions of HIF-1 bind to TAZ1 last. In addition, Fig. 6A indicates that between the N terminus of HIF-1 (including A and L1) is lower than 0.2 at the basin of bound state ( (TAZ1–HIF-1), about 0.63). This suggests that the N terminus of HIF-1 does not bind to TAZ1 tightly at bound state. We then calculated the within the different parts of the ligand. It is clear in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A that HIF-1 folds as it binds to TAZ1, except for part of the A helix of HIF-1. At unbound state, the folding level of C is higher than that of A and B. In addition, nonnative electrostatic interactions play an important role at the initial binding stage (0, no native interactions at this stage), which is favorable for guiding IDP to find its target. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B, the number of nonnative electrostatic interactions between TAZ1 and CITED2 is about twofold of that between TAZ1 and HIF-1 at the initial stage of the binary binding. The results agree with the above analysis of the binding barriers and kinetic rates.

Fig. 6.

The mean between different parts of ligand (HIF-1 or CITED2) and TAZ1 as a function of binding in the binary system, UH (A) and UC (B), and in the ternary system, CIH (C and E) and HIC (D and F). A, C, and D show the curves of HIF-1; B, E, and F show the curves of CITED2. SE values of data are shown.

The situation is a bit different in the HIF-1 replacing process in the ternary system (CIH pathway). As illustrated in Fig. 6C, because of the existence of CITED2, A, B, L1, and L2 (including the LPQL motif) of HIF-1 begin to bind to TAZ1 until the LPEL motif of CITED2 is away from the binding site. The C terminus of HIF-1 (including the C and L3) binds to TAZ1 first. In contrast, the existence of CITED2 causes the folding of B of HIF-1 later and C earlier in the CIH pathway than that without the prebound CITED2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and C). And this does not have a significant effect on the folding of A of HIF-1. However, the existence of CITED2 will not influence the level of nonnative electrostatic interactions between TAZ1 and HIF-1, and the nonnative electrostatic interactions between the two IDP ligands are not significant (SI Appendix, Fig. S7C).

For the CITED2 binding process in the binary system, it seems that the L1 region of the N terminus of CITED2 binds to TAZ1 first in the UC process (Fig. 6B), followed by the other parts. And the CITED2 folds gradually as binding to TAZ1 (shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). However, in the CITED2 replacing process in the ternary system (HIC pathway), A and L1 of CITED2 get in touch with TAZ1 first, while the C terminus, L2 region (including the LPEL motif), occupies the binding site until HIF-1 leaves the TAZ1. The existence of HIF-1 causes the folding of A earlier in the HIC pathway than that without the prebound HIF-1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6F). Moreover, in the ternary system, the C terminus (including the C and L3) of HIF-1 is the last part away from TAZ1 (HIC pathway), which is also the first part that binds to TAZ1 (CIH pathway); the N terminus (including the A and L1) of CITED2 leaves TAZ1 last (CIH pathway), which is the first part that binds to TAZ1 (HIC pathway). Besides, compared to the CITED2 binding in the binary system, the existence of HIF-1 decreases the level of nonnative electrostatic interactions between TAZ1 and CITED2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 B and D). It is obvious that the prebound HIF-1 has nonnative electrostatic interactions with CITED2 at the rate-limited step of HIC pathway (switch of LPQL/LPEL motif).

Aiming to find out the crucial residues in the binding process, we calculated the value of different binding pathways. For HIF-1 binding in the binary system (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B), most values of HIF-1 are lower than 0.2, except for Gly791, Leu792, and Gln824. The residues with relatively high values locate on the A, LPQL motif, and the C terminus of HIF-1, while, for the HIF-1 replacing process in the ternary system (CIH pathway; SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A and B), the values of A and LPQL motif decrease and the values of the C terminus increase when compared with the HIF-1 binding process without the prebound CITED2. These results agree with the analysis of contact map and distribution above. For both CITED2 binding and replacing in the binary and ternary systems (SI Appendix, Figs. S8 C and D and S9 C and D), the N terminus of CITED2 has higher values than other parts of CITED2. The existence of the prebound HIF-1 will lead to higher values on N terminus of CITED2.

Some experimental values of HIF-1 are labeled in SI Appendix, Fig. S8B. Most simulated values at these residue locations are lower than 0.2, in agreement with the experimental values. The experimental results demonstrate that native hydrophobic binding interactions have not been created yet at the rate-limiting TS for binding between TAZ1 and HIF-1, which is consistent with our findings that the ligand changes its conformation and folds after the TS. However, the mutation V825A (red dot in SI Appendix, Fig. S8B) has a much higher experimental value (0.34) than the simulated one (0.12). We have noticed that both and are negative (34), which means that this mutation will stabilize both the TS and the bound state. But, in the theoretical method of value calculation, we assume that the mutation will break the interactions between this residue and the others (35). And the theoretical value calculation will be sensitive for the residue sites with high values and accurate for the value results driven by native contacts. Perhaps this can explain the difference between these two values.

Conclusions

The TAZ1 domain of CBP is reported to be associated with two different IDP targets that share parts of the binding site respectively. It has been found that, in the solution of TAZ1 with two different targets HIF-1 and CITED2, TAZ1 prefers to form a complex with CITED2 rather than HIF-1. Aiming to determine the underlying mechanism of the competitive binding between HIF-1 and CITED2, we performed coarse-grained MD (CGMD) simulations by developing the SBM of TAZ1, HIF-1, and CITED2 systems. Several main states (UB, HB, CB, and IS) and a substate HB1 can be quantified on the free energy surface of the ternary system (TAZ1, HIF-1, and CITED2). The simulated mechanism is consistent with the previous experimental hypothesis about the replacing process and the apparent affinity. The results suggest the dominant position of forming TAZ1–CITED2 complex in the ternary system in both thermodynamics and kinetics. For the replacing processes, exiting the prebound ligand is time-consuming, and the switch of the LPQL/LPEL motif that occupies in the binding site is the rate-limited step. In addition, the analysis about the interchain and intrachain contacts between TAZ1 and the target shows the different binding order of each domain in binding and replacing processes with (ternary system) or without (binary system) the prebound ligand. In the replacing process with the prebound CITED2 (CIH pathway), the crucial LPQL and B domain of HIF-1 access their binding site after the intermediate state, which is different from that in the binding process of HIF-1 without the prebound CITED2. In the HIC pathway, the LPEL motif and the C terminus of CITED2 begin to bind TAZ1 after the LPQL motif of HIF-1 leaves TAZ1, different from the direct binding process of CITED2 without the prebound HIF-1. Besides, the presence or absence of the prebound ligand will also change the distribution of the values.

The interactions among the three molecules, TAZ1, HIF-1, and CITED2, are related to the cellular transcriptional and hypoxic negative feedback regulations. Our explorations of the competitions of the two IDP ligands binding to TAZ1 establish a connection between the simulation and experimental results with a more detailed description of “hypersensitive regulatory switch” at the molecular level, which is significant for the research of underlying biological functions of IDPs.

Methods

NMR structures 1L8C (10) and 1R8U (15) were used for preparing the initial models of TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complexes. Full-length HIF-1 and CITED2 are 51 and 50 amino-acid (a.a.) proteins (776 to 826 and 220 to 269), respectively. The initial coarse-grained SBM of TAZ1–HIF-1 and TAZ1–CITED2 complexes was generated using the SMOG (a versatile software package for generating structure-based models) on-line toolkit (35–38). There are three ions linked with TAZ1 with coordination bonds, modeled by one bead with two positive charges (+2e) for each ion. In the present work, the weighted contact map was built with all 20 configurations in each NMR structure. Each native contact was identified by the CSU algorithm (39). The weighted coefficient (for intermolecular contacts and the contacts within HIF-1/CITED2) is the frequency of occurrence in all of the configurations, similar to the method in our previous studies (25). All simulations were performed with Gromacs 4.5.5 (40). The CGMD simulations used Langevin equation with constant friction coefficient . The cutoff length for nonbonded interactions was set to 3.0 nm. To enhance the sampling of binding events, a strong harmonic potential was added if the distance between the center of mass of TAZ1 and HIF-1 or between the center of mass of TAZ1 and CITED2 is >6 nm (41). The detailed steps and settings are provided in SI Appendix.

Data Availability.

The relevant raw data can be found in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/db9pm/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Wright and Rebecca Berlow for helpful discussions and comments. W.-T.C. thanks Network and Computing Center, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Science, and Computing Center of Jilin Province for computational support. W.-T.C. thanks the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 21603217 and 21721003, and Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grant 2016YFA0203200.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The relevant raw data can be found in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/db9pm/).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1915333117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wright P. E., Dyson H. J., Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol. 293, 321–331 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunker A. K., et al. , Intrinsically disordered protein. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 19, 26–59 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uversky V. N., Natively unfolded proteins: A point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 11, 739–756 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 54–60 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 197–208 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin A. C., et al. , Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415, 141–147 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho Y., et al. , Systematic identification of protein complexes in saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415, 180–183 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright P. E., Dyson H. J., Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 18–29 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharya S., et al. , Functional role of p35srj, a novel p300/CBP binding protein, during transactivation by HIF-1. Genes Dev. 13, 64–75 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dames S. A., Martinez-Yamout M., De Guzman R. N., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., Structural basis for Hif-1/CBP recognition in the cellular hypoxic response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5271–5276 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman S. J., et al. , Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5367–5372 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lando D., Peet D. J., Whelan D. A., Gorman J. J., Whitelaw M. L., Asparagine hydroxylation of the hif transactivation domain: A hypoxic switch. Science 295, 858–861 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohn K. W., et al. , Properties of switch-like bioregulatory networks studied by simulation of the hypoxia response control system. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3042–3052 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arany Z., et al. , An essential role for p300/CBP in the cellular response to hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12969–12973 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Guzman R. N., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., Interaction of the TAZ1 domain of the CREB-binding protein with the activation domain of CITED2: Regulation by competition between intrinsically unstructured ligands for non-identical binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3042–3049 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman S. J., et al. , Structural basis for negative regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by CITED2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 10, 504–512 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berlow R. B., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., Hypersensitive termination of the hypoxic response by a disordered protein switch. Nature 543, 447–451 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W., Wang J., Zhang J., Takada S., Wang W., Overcoming the bottleneck of the enzymatic cycle by steric frustration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 238102 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W., Wang J., Zhang J., Wang W., Molecular simulations of metal-coupled protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 30, 25–31 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu X., Gan L., Wang E., Wang J., Quantifying the topography of the intrinsic energy landscape of flexible biomolecular recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2342–E2351 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo S., Li W., Takada S., Allosteric conformational change cascade in cytoplasmic dynein revealed by structure-based molecular simulations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005748 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu W. T., Wang J., Quantifying the intrinsic conformation energy landscape topography of proteins with large-scale open–closed transition. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 1015–1022 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okazaki K., Koga N., Takada S., Onuchic J. N., Wolynes P. G., Multiple-basin energy landscapes for large-amplitude conformational motions of proteins: Structure-based molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11844–11849 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W., Wang W., Takada S., Energy landscape views for interplays among folding, binding, and allostery of calmodulin domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 10550–10555 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu W. T., Chu X., Wang J., Binding mechanism and dynamic conformational change of C subunit of PKA with different pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7959–E7968 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y., Tang C., Wang E., Wang J., Exploration of multi-state conformational dynamics and underlying global functional landscape of maltose binding protein. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002471 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu X., et al. , Importance of electrostatic interactions in the association of intrinsically disordered histone chaperone Chz1 and histone H2A.Z-H2B. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002608 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu X., et al. , Dynamic conformational change regulates the protein-DNA recognition: An investigation on binding of a Y-family polymerase to its target DNA. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003804 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu W. T., Clarke J., Shammas S. L., Wang J., Role of non-native electrostatic interactions in the coupled folding and binding of PUMA with Mcl-1. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005468 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S., Rosenberg J. M., Bouzida D., Swendsen R. H., Kollman P. A., The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 1011–1021 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S., Rosenberg J. M., Bouzida D., Swendsen R. H., Kollman P. A., Multidimensional free-energy calculations using the weighted histogram analysis method. J. Comput. Chem. 16, 1339–1350 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das R. K., Pappu R. V., Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13392–13397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y., Formankay J. D., Chan H. S., Sequence-specific polyampholyte phase separation in membraneless organelles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 178101 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindström I., Andersson E., Dogan J., The transition state structure for binding between TAZ1 of CBP and the disordered Hif-1 CAD. Sci. Rep. 8, 7872 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clementi C., Nymeyer H., Onuchic J. N., Topological and energetic factors: What determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en-route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 298, 937–953 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noel J. K., Whitford P. C., Sanbonmatsu K. Y., Onuchic J. N., SMOG@ctbp: Simplified deployment of structure-based models in GROMACS. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W657–W661 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noel J. K., Whitford P. C., Onuchic J. N., The shadow map: A general contact definition for capturing the dynamics of biomolecular folding and function. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 8692–8702 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lammert H., Schug A., Onuchic J. N., Robustness and generalization of structure-based models for protein folding and function. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 77, 881–891 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobolev V., Sorokine A., Prilusky J., Abola E. E., Edelman M., Automated analysis of interatomic contacts in proteins. Bioinformatics 15, 327–332 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hess B., Kutzner C., Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tribello G. A., Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Camilloni C., Bussi G., PLUMED 2: New feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604–613 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The relevant raw data can be found in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/db9pm/).