Significance

Chemotaxis to microbial metabolites in the GI tract plays a key role in regulating bacterial colonization and pathogenesis. Chemotaxis to indole, one of the prominent GI-tract metabolites, remains poorly understood. In this work, we describe how two major chemoreceptors, Tar and Tsr, mediate opposite responses to indole. The difference in the kinetics of these responses causes an inversion from a repellent to an attractant response over time. Cells migrated toward regions of high indole concentration only if they had previously adapted to indole. Otherwise, they were repelled. Thus, indole has the potential to segregate cells based on their state of adaptation. This bipartite response to indole may shape the development of microbial communities in the GI tract.

Keywords: metabolite, flagella, switching, adaptation, chemoreceptors

Abstract

Bacterial chemotaxis to prominent microbiota metabolites such as indole is important in the formation of microbial communities in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. However, the basis of chemotaxis to indole is poorly understood. Here, we exposed Escherichia coli to a range of indole concentrations and measured the dynamic responses of individual flagellar motors to determine the chemotaxis response. Below 1 mM indole, a repellent-only response was observed. At 1 mM indole and higher, a time-dependent inversion from a repellent to an attractant response was observed. The repellent and attractant responses were mediated by the Tsr and Tar chemoreceptors, respectively. Also, the flagellar motor itself mediated a repellent response independent of the receptors. Chemotaxis assays revealed that receptor-mediated adaptation to indole caused a bipartite response—wild-type cells were attracted to regions of high indole concentration if they had previously adapted to indole but were otherwise repelled. We propose that indole spatially segregates cells based on their state of adaptation to repel invaders while recruiting beneficial resident bacteria to growing microbial communities within the GI tract.

Chemotaxis toward environmental cues regulates the formation of bacterial communities and attachment to host cells (1–4). The environmental cues in response to which motile bacteria migrate include nutrients such as amino acids and sugars, oxygen, pH, and temperature gradients (5–11). Bacteria also respond to neurotransmitters and hormones (12) and to metabolites that regulate bacterial physiology and shape the formation of microbial communities (13–15).

The binding of chemoeffector molecules to the chemoreceptors of Escherichia coli modulates the activity of the receptor-associated kinase CheA. E. coli carry five types of chemoreceptors: Tar, Tsr, Trg, Aer, and Tap, out of which Tar and Tsr are dominant. The activated CheA autophosphorylates using ATP and in turn phosphorylates the chemotaxis response regulator CheY. CheY-P binds to a switch in the flagellar motor to promote clockwise (CW) rotation in an otherwise counterclockwise (CCW)-rotating flagellum. Such motor reversals mediate alternating runs and tumbles, which enable the cell to steer its direction of swimming in response to a chemical gradient (16).

To continue migrating up a chemical gradient (positive chemotaxis) or down a chemical gradient (negative chemotaxis), cells must constantly reset the activity of CheA. This resetting, known as adaptation, involves the covalent modification of the receptors by two enzymes—CheR and CheB. When an attractant binds and CheA activity falls, the slow constitutive activity of a methyltransferase, CheR, leads to higher methylation of the receptor. Methylation increases the activity of CheA until it reaches prestimulus levels. The cells adapt and are ready to respond to higher concentrations of the attractant. When a repellent binds and CheA activity increases, a methylesterase, CheB, becomes phosphorylated. CheB-P rapidly demethylates the receptor to decrease the activity of CheA back to its prestimulus levels. Once again, the cell adapts and is ready to respond to higher concentrations of the repellent.

Among the important metabolites that control chemotactic behavior (17, 18), indole has received wide attention for its role in regulating a broad range of bacterial phenotypes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including motility, stress responses, biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, and virulence (15, 19–22). Indole is a product of tryptophan and is produced by several species that inhabit the GI tract, especially those belonging to the phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria (23). Indole promotes homeostasis in the microbial community of the GI tract by inhibiting virulence and colonization of host cells by several pathogens, including enterohemorrhagic E. coli (24, 25), Salmonella enterica (22, 26), and Vibrio cholerae (27). Indole also promotes phenotypes linked to virulence and colonization in other pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Clostridium difficile (23, 28, 29). These varying effects of indole probably depend on its concentrations, which can fluctuate over a wide range (0.2 to 6.5 mM) in the GI tract (30).

Previous reports suggest that indole induces a chemorepellent response in S. enterica and E. coli (17, 18) and that the response is mediated by the one of the two major chemoreceptors, Tsr (31–33). Yet, strains of E. coli lacking all major chemotaxis genes other than cheY also exhibit a repellent response to indole (34). Other studies suggest that indole induces attractant responses instead (32, 35). Thus, the mechanisms underlying these diverse chemotaxis responses to indole remain poorly understood.

In this work, we explored the mechanisms underlying chemotaxis to indole and observed selective partitioning of E. coli on the basis of their memory of exposure to indole. Our results suggest that indole produced by microbial communities retains resident indole-responsive commensals while preventing invading indole-responsive bacteria from joining the community.

Results

Chemotaxis Response to a Low Concentration of Indole.

We measured the chemotactic response of individual cells by tracking the motor CWbias, namely the fraction of the time that it rotates CW, using tethered-cell assays. Perfusion chambers were employed to stimulate tethered cells with indole. An increase in CWbias upon stimulation is indicative of a chemorepellent response, whereas a decrease in CWbias is indicative of a chemoattractant response (36). A strong and reproducible CW repellent response was observed immediately after stimulating wild-type cells with 20 μM indole. The response precisely adapted to the original value within 30 to 50 s (Fig. 1A). When indole was replaced with motility buffer, it had the opposite effect; the CWbias decreased initially and subsequently adapted to its prestimulus value (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

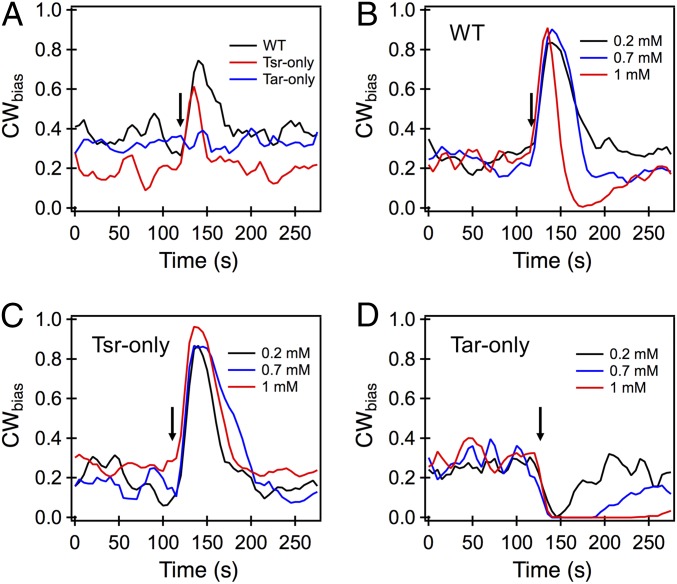

Fig. 1.

(A) Averaged response of tethered cells to 20 μM indole. The arrow indicates the approximate time of exposure to indole. The wild type (black curve) and the tar knockout (red curve) both exhibited a brief increase in CWbias, indicating a repellent response. The response precisely adapted such that the pre- and poststimulus CWbias was similar. The tsr knockout showed no response to the stimulation. (B) The short-time CW repellent response of wild-type cells was evident over the entire range of concentrations tested, as indicated by the increase in CWbias ∼20 to 50 s following stimulation. At longer times (>50 s), an attractant response was evident when cells were treated with 1 mM indole. A similar inversion was observed upon treatment with 2 mM indole (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). (C) A strong repellent response was observed in the case of the Tsr-only mutant over the entire range of indole concentrations tested. The adaptation was precise in each case. (D) Attractant responses were observed in the Tar-only mutant over the 0.2 to 1 mM concentration range. The delay in adaptation to the response increased with indole concentration. All response curves represent an average over n = 11 to 21 cells. The average error was 0.01.

Addition of 20 μM indole to isogenic mutant cells lacking the Tar receptor, which we refer to as Tsr-only because Tsr is their only high-abundance receptor, induced a similar but shorter CW repellent response of only ∼25 s (Fig. 1A). Addition of 20 μM indole to isogenic mutant cells lacking the Tsr receptor, which we refer to as Tar-only, did not evoke either a detectable repellent or attractant response. This result demonstrates that Tsr mediates a repellent response to 20 μM indole and adapts rapidly, presumably through demethylation of Tsr by CheB-P.

Chemotaxis Responses to Higher Concentrations of Indole.

At higher concentrations of indole (200 to 700 μM), wild-type cells continued to exhibit a repellent response that adapted precisely. However, when the cells were treated with 1 mM indole, the repellent response inverted to an attractant response after about 50 s (Fig. 1B). A similar time-dependent inversion was observed at 2 mM indole (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A).

The Tsr-only strain exhibited CW repellent-only responses that adapted precisely to the prestimulus levels with 200 μM to 1 mM indole (Fig. 1C). Again, adaptation presumably occurs via CheB-P–mediated demethylation. The increase in the CWbias was relatively insensitive to indole concentrations. The absence of an inverted response after addition of indole, even at 2 mM (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), suggested that Tar mediates the delayed attractant response that was observed with the wild type. The Tar-only strain exhibited a strong CCW attractant response to 200 μM to 1 mM indole (Fig. 1D), and also to 2 mM indole (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). The absence of the repellent response was consistent with the notion that Tsr mediates the initial repellent response that was observed in the wild type. Adaptation in the Tar-only mutant was slower and presumably occurs via CheR-mediated methylation. The adaptation occurred with increasing delays as the concentration of indole increased, likely because the deviation of CheA activity from its basal value increased with indole levels. This suggests that the attractant response does not saturate even at 1 mM indole.

Overall, the biphasic response of wild-type cells to higher concentrations of indole seems to occur due to the combination of a strong but rapidly adapting repellent response mediated by Tsr and a prolonged, slowly adapting attractant response mediated by Tar. The repellent response masks the attractant response until the cells have adapted via demethylation of Tsr.

Responses to the Removal of Indole.

The replacement of indole with motility buffer (MB) had different effects on the wild-type, Tar-only, and Tsr-only cells. The wild type exhibited attractant-like CCW responses when indole at 20 or 200 μM was replaced with MB (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Removal of 700 μM or higher indole induced rapid repellent responses followed by extended attractant responses that did not adapt over 100 s.

The Tsr-only mutant generally exhibited extended attractant responses upon the removal of indole, with adaptation slow because it requires methylation of Tsr. The removal of 2 mM indole induced a biphasic response, with a brief repellent response followed by a strong attractant response that did not adapt over 100 s. We do not know the cause of this brief repellent response. However, it is unlikely to arise due to demethylation-mediated inversion in Tsr’s repellent response to indole since no attractant response was ever observed in the Tsr-only strain when indole was added.

The Tar-only mutant exhibited repellent responses that adapted to baseline within 50 to 75 s, presumably via CheB-P–mediated demethylation, when ≥200 μM indole was removed. The Tar-only cells did not give a detectable response to the removal of 20 μM indole, just as they gave no detectable response to addition of 20 μM indole. All of these data are consistent with the notion that indole is sensed by Tsr as a repellent and by Tar as an attractant.

Indole Responses Are Not Mediated by Changes in Cytoplasmic pH.

Previous work showed that Tar mediates an attractant response when the intracellular pH is decreased, whereas Tsr mediates a repellent response (37). As indole at high concentrations reportedly permeates the membrane and decreases the cytoplasmic pH (38, 39), we tested whether the biphasic response to indole occurs through the known pH-mediated signaling mechanism. To do this, we expressed a pH-sensitive fluorescent protein in the wild-type strain (Materials and Methods). Cells attached to a glass surface in a perfusion chamber were treated with a mix of 40 mM benzoate and buffer (at pH 6.0), following previous approaches (40, 41), and illuminated at an appropriate excitation wavelength. Benzoate in its protonated form permeates the membrane and equalizes the cytoplasmic and extracellular pH. A strong change in emission intensities was observed when pH 7.0 MB was exchanged with a buffer containing 40 mM benzoate at pH 6.0 (Fig. 2, Left). Yet, repeated cycles of exposure to 2 mM indole failed to elicit a measurable change in emission intensity (Fig. 2, Right). This result suggests that, even upon exposure to the highest indole concentration employed in this work, no change occurred in the cytoplasmic pH, at least within the detection limits of our experimental setup.

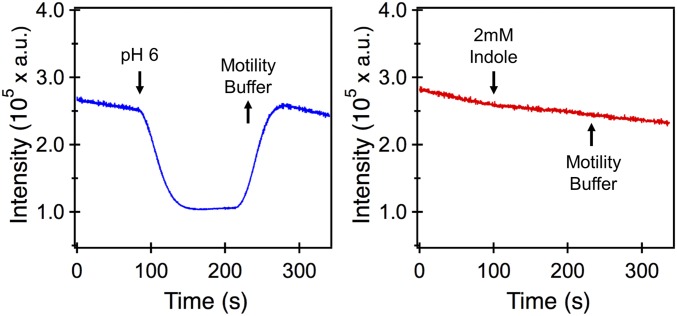

Fig. 2.

(Left) Emission intensities of a pH-sensitive fluorophore that was expressed in the wild-type strain are indicated. The cells were initially exposed to a neutral buffer solution (MB, pH 7.0). At ∼90 s, the buffer was exchanged with an acidic medium (MB, pH 6.0 plus 40 mM benzoate). The acidification of the intracellular environment reduced the emission intensities. The intensities were restored to the prestimulus values when the medium was replaced with MB (pH 7.0) at ∼210 s. (Right) Cells were stimulated with 2 mM indole at ∼90 s. No measurable change in the emission intensities was observed. Removal of indole also did not cause a significant change in intensities. Signals were obtained from ∼100 to 200 cells. a.u., arbitrary units.

Response to Step Increments in Indole Concentrations.

Because the repellent response adapted much more quickly than the attractant response (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that wild-type cells previously adapted to indole would exhibit an attractant-only response upon further stimulation. To test this hypothesis, we repeatedly stimulated the same population of wild-type tethered cells with increasing concentrations of indole (Fig. 3A). Each time the cells were stimulated with indole at ≤700 μM, an immediate repellent response that adapted precisely was observed. Once adapted to 700 μM indole, however, the cells exhibited attractant-only responses when exposed to higher concentrations of indole. The brief Tsr-mediated repellent response that was observed in nonadapted cells (Fig. 1A) was absent in these adapted cells.

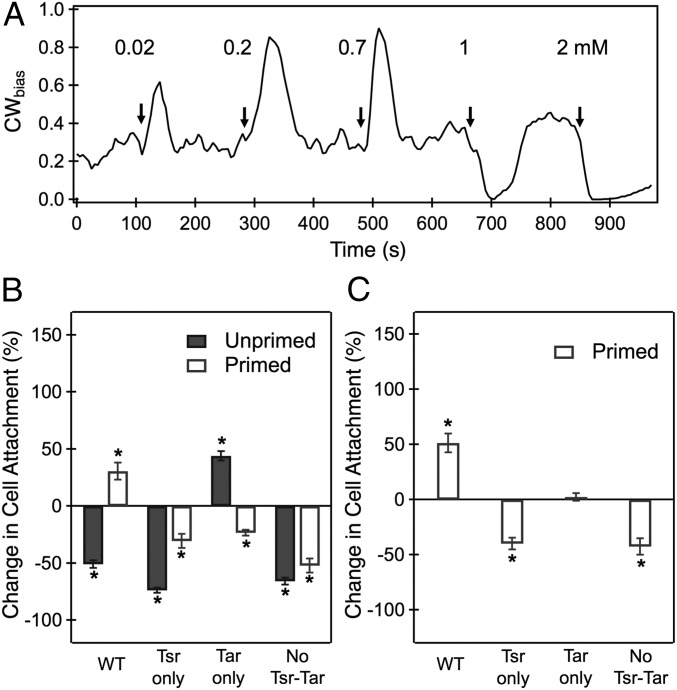

Fig. 3.

(A) Wild-type cells were stimulated with step increments in the concentration of indole at the times indicated by the arrows. Upon adaptation to 0.7 mM indole, attractant-only responses were observed at higher stimulation levels. The average error was 0.07 (n = 11 motors). (B and C) The nature and magnitude of the chemotaxis response in the transwell-based chemotaxis assay are indicated for several strains. The ordinate in B reflects the percentage difference in cell attachment to the agar source containing 2 mM indole relative to the basal attachment. The basal attachment is determined from the number of unprimed cells adhered to agar pads that contain no indole (agar pads and reservoir contain MB only). The basal value depends on chance encounters and attachment of the cells with the polylysine-coated agar surface in the absence of chemical signals, and it has been normalized to 0 for each strain. Positive (negative) attachment values indicate positive (negative) chemotaxis. A +100% value indicates that recruitment to the agar surface is twice that seen through random chance. The ordinate in C reflects the percentage difference in the attachment of primed cells to the agar source containing 2 mM indole relative to the attachment of primed cells in the gradient-less control. The gradient-less control includes agar pads soaked in the same concentration of indole as the cell reservoir (700 μM). Two biological and three technical replicates were carried out for each condition. The mean attachment values were calculated over 4,000 to 10,000 cells. *P < 0.05.

Effect of Adaptation to a Threshold Concentration of Indole on Chemotaxis to Indole-Containing Surfaces.

Because high indole levels (1 mM and above) induced an attractant response in cells that had previously adapted to the threshold level (∼700 μM), we hypothesized that such adapted (primed) cells should respond to indole as an attractant and migrate toward indole-rich substrates. To test this idea, we employed an inverted transwell assay previously developed in our laboratory (42, 43), depicted in SI Appendix, Fig. S2. Agar pads presoaked in 2 mM indole were brought into contact with wild-type cells swimming in a 2-mL reservoir of MB. Agar contact with the reservoir fluid rapidly established an indole gradient in the reservoir. The cells in the reservoir that responded to the gradient either migrated away (negative chemotaxis) or toward (positive chemotaxis) the indole-rich agar pads. The number of cells attached to the poly-l-lysine–coated agar pads was quantitatively determined following 5 min of exposure (Materials and Methods). In the primed case, the 2-mL MB reservoir contained ∼700 μM indole, and the cells were allowed to adapt to it for 30 min prior to being placed in contact with agar. In the unprimed case, the 2-mL MB reservoir contained no indole during the 30-min incubation. The basal attachment expected due to chance encounters of motile cells with the agar surface over 5 min was determined in separate measurements in which no indole was added to the agar or the reservoir. To rule out the possibility that the primed cells attached in greater numbers because of non–chemotaxis-related effects of indole, an additional gradient-less control was included in which primed cells were exposed to agar that contained the same concentration of indole (700 μM).

As shown in Fig. 3B, primed wild-type cells that were exposed to agar pads containing 2 mM indole (positive gradient) attached in higher numbers relative to the basal value (in the absence of indole), indicating an attractant response. Primed wild-type cells exposed to a positive gradient of indole also attached in higher numbers relative to primed wild-type cells that were exposed to uniform indole concentrations (gradient-less control; Fig. 3C). This result confirmed that the increased attachment of the primed cells was due to positive chemotaxis (chemoattraction) toward the indole source. In contrast, the unprimed wild-type cells attached in lower numbers than the basal value, indicating a repellent response to indole. The raw data are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3.

The chemotaxis assays were repeated with mutants lacking Tsr, Tar, or both Tsr and Tar. With the Tsr-only mutant, unprimed as well as primed cells exhibited negative chemotaxis (repellent response), consistent with the results with tethered cells (Fig. 3B). As shown in Fig. 3C, the primed Tsr-only cells exhibited negative chemotaxis relative to the gradient-less control. In the Tar-only mutant, unprimed cells exhibited an attractant response (Fig. 3B), as in the tethered-cell assay. The primed cells appeared to exhibit a weak repellent response, but the result was not significant relative to the corresponding gradient-less control (Fig. 3C). A repellent response was clearly seen in the Δtar Δtsr double mutant, whether the cells were primed or unprimed (Fig. 3B). The response was significant even when compared with the gradient-less control (Fig. 3C). These repellent responses occurred despite the absence of either high-abundance receptor. As will become apparent later, we believe that a part of the repellent response arises from a receptor-independent mechanism rather than a response mediated by the low-abundance receptors Trg, Tap, and Aer.

Is There a Receptor-Independent Response to Indole?

To determine the reason for the repellent response in the Δtsr Δtar strain, we stimulated tethered cells of the double mutant with indole. These cells exhibited a strong repellent response that showed little adaptation over 200 s (Fig. 4A). The small and slow adaptation suggested that kinase (CheA) activity itself was not perturbed significantly and that the majority of the observed repellent response might be receptor-independent.

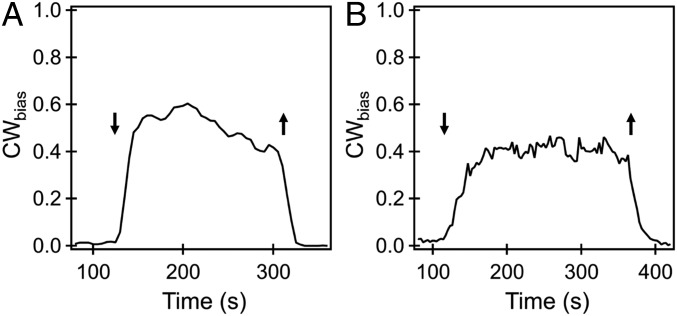

Fig. 4.

(A) Averaged response of a Δtar Δtsr double mutant to 1 mM indole. The entry and exit of indole from the flow cell are indicated by the downward and upward arrows, respectively. A repellent-only response was observed with minimal adaptation. Response curves were averaged over n = 22 cells, and the mean error was 0.01. (B) The averaged CWbias of the CheY-less FliGCW-FliGWT motors that switch is indicated. Stimulation with 2 mM indole at ∼110 s increased the CWbias, and removal of indole restored the bias to prestimulus levels. The curve was averaged over n = 9 cells, and the average error in bias measurements was 0.05.

The flagellar switch consists of the FliM and FliN complexes, to which CheY-P binds, and the FliG ring, which forms the track on which the stators act to rotate the motor (44). We hypothesized that indole permeates the membrane and interacts with the flagellar switch, either directly or indirectly, to promote CW rotation. To test the hypothesis, we generated a ΔcheY strain in which the motors are still capable of switching. Although motors usually rotate only CCW in a ΔcheY strain, they are able to switch in the presence of a few mutant FliGCW subunits in an otherwise wild-type FliG ring (45). These mutant subunits are locked in the CW conformation (46), and they destabilize the FliG ring to allow switching to occur through cooperative interactions when they are present in the right proportion relative to wild-type FliG subunits (45). Mixed FliG motors were generated by expressing the mutant subunits from an IPTG (isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside)-inducible vector (induced with 5 μM IPTG), while the native FliG subunits were expressed from the genomic locus. The ΔcheY cells with mixed FliG motors rotated predominantly CCW, but when stimulated with 2 mM indole they exhibited a strong repellent response that did not adapt over 250 s (Fig. 4B). Tethered cells belonging to a ΔcheY strain that carried wild-type FliG subunits continued to rotate CCW only following the addition of 2 mM indole. Because the absence of CheY cuts all communication between the receptor patch and the flagellar motor, this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that part of the repellent response to high concentrations of indole is receptor-independent.

Discussion

Our experiments quantified the Tsr-mediated repellent response to indole. This is most easily observed in the Tsr-only strain (Fig. 1 A and C). Cells responded strongly to the addition of 20 μM indole (Fig. 1A), and the strength of the response did not increase significantly at concentrations above 200 μM (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). The adaptation times, presumably controlled by CheB-P–mediated Tsr demethylation, were relatively short and similar over the range of indole concentrations tested (∼30 to 50 s).

We also demonstrated that Tar mediates an attractant response to indole, but only at high concentrations. This is best seen in the Tar-only strain that exhibited strong attractant responses to indole at ≥200 μM or higher (Fig. 1D). The time required for adaptation, presumably influenced by the slow Tar methylation by CheR, increased with indole concentration. The CWbias is very sensitive to CheY-P levels (47–49), and it drops to 0 even for small reductions in CheY-P levels. It takes longer for CheY-P levels, and consequently the CWbias, to recover to the basal value when the reduction in CheY-P is more significant. Therefore, the increasing delays in adaptation in Fig. 1D suggest that higher indole levels cause greater reductions in CheY-P levels in the Tar-only strain. Based on this, we conclude that the attractant response to indole requires concentrations of at least 1 mM, and probably higher, to saturate. We also conclude that Tsr has a higher affinity for indole than Tar.

The response of wild-type cells to indole is a combination of the repellent response mediated by Tsr and the attractant response mediated by Tar. At 20 and 200 μM, the wild-type cells sense indole as a repellent through Tsr, and the response adapts quickly (Fig. 1A). At indole concentrations of ≥1 mM (Fig. 1B), the Tsr-mediated repellent response initially masks the Tar-mediated attractant response until the rapid receptor demethylation by CheB-P deactivates CheA adequately for the attractant response to be revealed. The attractant response then adapts slowly due to CheR-mediated methylation of the receptors. Thus, the binding affinities of Tsr and Tar for indole and the asymmetric kinetics of methylation and demethylation play a key role in the biphasic wild-type response.

Tsr-mediated repellent and Tar-mediated attractant responses are known to occur when the cytoplasmic pH decreases. However, experiments with a pH-sensitive fluorescent protein revealed that even at the highest concentration tested (2 mM), indole did not produce a measurable change in cytoplasmic pH (Fig. 2). Thus, sensing of changes in cytoplasmic pH in our study is not involved in the receptor responses to indole. The following two questions remain: How does indole interact with the two receptors, and do the indole-binding sites localize to the same region of the proteins in Tsr and Tar? A previous study reported that E. coli cells devoid of periplasm continued to exhibit repellent responses to indole, which suggests that the soluble periplasmic protein is not involved, at least in repellent sensing by Tsr (50). However, the interpretation is not straightforward, due to the observed motor-mediated effects (Fig. 4B). Another confounding factor is that the strength of the allosteric coupling interactions within the signaling complex arrays in the wild type are unlikely to be preserved in the Tsr-only or Tar-only strains, where one or the other major receptor is lacking (51). Thus, the wild-type response may not be a simple summation of the Tsr-only and Tar-only responses. The mechanisms of indole sensing are the subjects of ongoing investigations.

An important consequence of the rapid adaptation of the repellent response at intermediate indole concentrations and the slow dynamics of the attractant response is that cells preadapted to a threshold concentration of indole exhibit an attractant-only response at higher concentrations. Tethered wild-type cells previously adapted to ∼700 μM indole sense it as an attractant at 1 mM and higher concentrations; the brief repellent responses seen at these concentrations in nonadapted cells (Fig. 1B) are not seen in adapted cells (Fig. 3A). Cells previously adapted to 200 μM or lower concentrations of indole continue to sense it as a repellent. These data suggest that a threshold indole concentration of ∼700 μM bifurcates the cell response depending on its recent exposure to the molecule.

The above argument also suggests that wild-type swimming cells adapted to the threshold indole level (∼700 μM) will be attracted to sources of higher indole concentrations, whereas those not adapted to ∼700 μM indole will be repelled from those sources. This was confirmed by our in vitro attachment assay (Fig. 3 B and C). Wild-type cells not previously exposed to the threshold level (unprimed cells) actively avoided agar plugs soaked in 2 mM indole. However, cells adapted to the threshold level (primed cells) were attracted to those agar plugs. This attraction depended on the presence of the Tar receptor, as primed and unprimed Tsr-only cells actively avoided the plugs. The unprimed Tsr-only cells avoided the plugs more than the primed Tsr-only cells, presumably because they had a larger proportion of indole-free, nonadapted Tsr receptors. The unprimed Tar-only cells were attracted to the indole-soaked agar plugs, but the primed Tar-only cells were not. In the case of the strains lacking both Tar and Tsr, the primed as well as the unprimed cells avoided the indole-soaked agar plugs, and tethered cells of this strain exhibited strong, nonadapting repellent responses to indole (Fig. 4A).

To determine if the repellent response seen in the Δtar Δtsr double mutants was independent of input from chemoreceptors, we measured the responses of tethered cells belonging to a strain that lacked the chemotaxis response regulator CheY and carried a mix of wild-type and CW-locked FliG subunits in its C ring (46, 52). Motors in strains lacking CheY rotate CCW only because the large free energy difference between the CW and CCW conformations of the flagellar switch makes it unlikely that the motor will rotate CW, even for a short time (53). Motors containing both types of FliG subunits exist in a metastable state that can switch, as the CW-locked FliG subunits lower the energy difference between the two rotational states (45). We hypothesized that indole acts on the motor, directly or indirectly, to further reduce the difference in free energy between the two conformations of the switch, thereby increasing the CWbias in a receptor-independent manner. Indeed, upon addition of 2 mM indole to such cells, a strong and nonadapting repellent response was observed (Fig. 4B). It is unclear whether indole interacts directly with the switch complex or through another molecule. However, this finding suggests that indole may act as a chemorepellent even to flagellated bacteria that lack a specific chemoreceptor for sensing it.

The E. coli Tsr and Tar receptors mediate opposite responses to several types of signals, including temperature, pH, leucine, and certain neurotransmitters (9, 11, 12, 30, 45, 54, 55). In the cases of temperature and pH, the result is to bring cells to optimal environments of neutral pH and physiological temperatures. It is intriguing that the different responses to indole may have exactly the opposite effect, partitioning cells into “extreme” environments. Cells that have adapted to the threshold level (∼700 μM) will be attracted to still higher concentrations of the metabolite. In unadapted cells, such as those encountering an indole gradient for the first time, the repellent response will cause cells to swim away from indole-rich regions.

A direct consequence of the above mechanism is that bacteria that produce indole have a higher likelihood of adapting to it, and therefore will be attracted to indole-rich microbial communities. These niches are likely to be those inhabited by other indole-producing bacteria as well. As bacterial species that lack the tryptophanase-encoding tnaA gene do not produce indole, their receptors are unlikely to have adapted to the molecule, and therefore will likely be repelled by indole-rich regions. Bacteria lacking a specific chemoreceptor for indole may also be repelled through a receptor-independent repellent response.

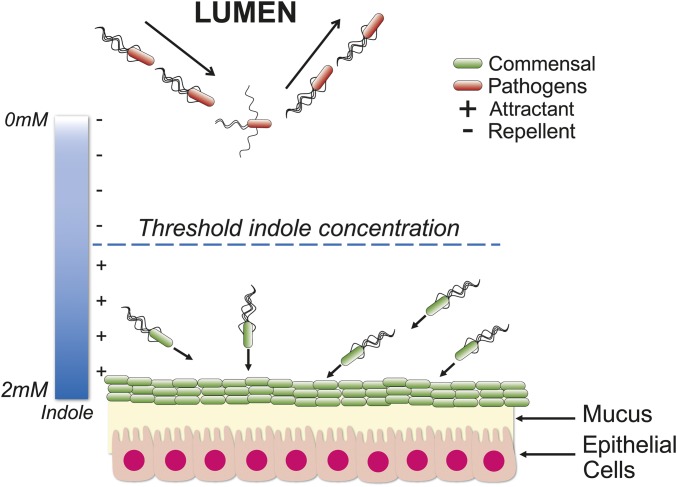

The interplay of repellent and attractant responses to indole may help guide the development of microbial niches in regions such as the GI tract. Indole-producing commensal microbes thrive in proximity to the mucosal interface in the GI tract; the concentrations of indole at these sites of production are expected to be much higher than the threshold level, considering that the diluted bulk concentrations in fecal samples can be as high as 6.5 mM (56). Commensal bacteria adapted to the threshold indole level will likely be retained in existing microbial communities because of attractant chemotaxis—although the precise number of motile species in the gut is unknown, several members of the phyla Firmicutes and Proteobacteria produce flagella (57). Away from the mucosal interface and toward the lumen of the GI tract, where indole levels are lower than the threshold (25), motile bacteria will be repelled by negative chemotaxis (Fig. 5). Thus, foreign ingested bacteria, including invading pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7 and S. enterica, are likely to be prevented by indole from gaining a foothold in the mucosa.

Fig. 5.

Distributional sorting by indole in the GI tract. The indole levels near the mucosal layers are shown as being above the threshold concentration. Primed cells will be attracted to the source, leading to retention of commensal bacteria in existing microbial communities. Away from the source, indole concentrations are shown as being lower than the threshold. Low indole concentrations prevent cells from becoming primed, inducing a repellent response. Unprimed cells will be induced to migrate toward the lumen.

It is likely that the GI-tract microbial communities complement the natural defense mechanisms of the host. They might do so by tuning the production of indole and exploiting the biphasic chemotaxis response to retain resident commensal bacteria and to prevent colonization by invading motile pathogens. If the receptor-independent repellent response is a general property of flagellar motors across bacterial species, motile bacteria lacking indole-specific chemoreceptors may also be discouraged from colonizing the intestinal mucosa. However, there exists a spatially varying mix of different microbial and host metabolite signals within the GI tract, some of which are potent chemoattractants (15, 58). The integrated chemotaxis response to a combination of different GI-tract signals may ultimately determine the efficacy of this defense strategy. Combinatorial studies on integrated signaling and chemotaxis response to a combination of metabolites and metabolic derivatives are needed to provide further insights.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Plasmids.

All strains were derivatives of E. coli RP437 (59) and are listed in Table 1. The two-step λ-red–mediated homologous recombination technique (60) was used to generate scarless, in-frame deletions. The deletions were confirmed via sequencing.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Relevant genotype | Source | |

| Strains | ||

| PL15 | HCB33 (RP437), sticky fliC allele | (63) |

| PL221 | PL15 Δtsr (Δnt 16–1644) Δtar (Δnt 16–1638) | This work |

| PL225 | PL15 Δtsr (Δnt 16–1644) | This work |

| PL278 | PL15 Δtar (Δnt 16–1638) | This work |

| PL14 | PL4 (ΔcheY, sticky fliC) with pTrc99A-fliGCW | (45) |

| CV1 | thr-1(Am) leuB6 his-4 metF159(Am) rpsL136 [thi-1 ara-14 lacY1 mtl-1 xyl-5 eda tonA31 tsx-78] with pCM18 | (30) |

| CV4 | CV1 Δtar | (64) |

| CV5 | CV1 Δtsr thr+ | (64) |

| CV11 | Δtar Δtsr | M.D.M. laboratory |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPL1 | pTrc99A-fliGCW | (35) |

| pCM18 | pTRKL2-PCP25RBSII-gfpmut3*-T0–T1 | (65) |

Cell Culture.

Overnight cultures were grown at 33 °C in tryptone broth (TB) followed by 1:100 dilution in 25 mL fresh TB for day cultures. The cultures were allowed to grow at 33 °C to an OD600 of 0.5. Antibiotics (100 µg/mL erythromycin and 25 µg/mL chloramphenicol) were added to the cultures where appropriate. Arabinose was added to the day cultures in the range of 0.001 to 0.1% (wt/vol) and IPTG was added to a concentration of 100 μM, where appropriate.

Tethered-Cell Assays.

The day cultures were harvested by pelleting cells by centrifugation (1,500 × g, 5 min). Cells were washed 2× in motility buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 67 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 µM methionine, 10 mM sodium lactate, pH 7.0). The final pellet was resuspended in 1 mL MB. Cells were then sheared to truncate flagellar filaments to stubs following previous approaches, and subsequently tethered to coverslips in perfusion chambers with the aid of sticky FliC filaments (61, 62). Cell rotation was recorded on a Nikon microscope (Optiphot 2) with a 20× phase objective at 60 fps and a digital camera (UI-3240LE-M-GL; IDS Imaging Development Systems). Videos of the rotation of the tethered cells were analyzed with custom-written codes in MATLAB (63). The rotation speeds were determined from Gaussian fits to the speed distributions. The CWbias (fraction of the time that the motor rotates CW) was determined as a function of time by employing a moving filter that averaged over 1.5 cell rotations, as done previously (47).

A three-directional valve (Hamilton) was employed to exchange the fluid in the perfusion chambers with MB or MB containing indole. The flow rate (260 μL/min) was controlled by a syringe pump (Fusion 200; Chemyx). Separate calibration experiments were performed with a colored fluid to estimate the average time of entry of chemoeffectors into the perfusion chamber after the initiation of flow.

pH Measurements.

A plasmid encoding a pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein (GFP-mut3*) was introduced into the wild-type RP437 strain. The expression level of GFP was controlled with IPTG (100 μM). An LED illumination source (SOLA SE II 365 light engine; Lumencor) and a standard Nikon GFP cube were employed to excite the fluorophores and to filter the emission. One hundred to 200 cells were excited in the field of view with a 60× water-immersion objective (Nikon Instruments). The emission was collected by a sensitive photomultiplier (H7421-40 SEL; Hamamatsu) after passing through a band-pass emission filter (FF01-542/27; AVR Optics). Custom-written LabVIEW codes were employed to record the photon count over time. For calibration purposes, the emission from the cells was measured for 100 s in MB. Then, the medium was exchanged for one containing 40 mM benzoate/MB at pH 6.

During measurements of the effect of indole on internal pH, the emission from the cells was measured for the first 100 s in MB. Then, MB was replaced with MB containing 2 mM indole while continuing the intensity measurements. The cells were allowed to equilibrate for 3 min before switching back to MB.

In Vitro Chemotaxis and Attachment Assay.

A thin agar layer was poured into individual transwell inserts (Nunc cell-culture inserts) and then soaked overnight in motility buffer or in motility buffer containing 2 mM indole. The agar surface was coated with poly-l-lysine to facilitate stable attachment of the cells. The inserts were then carefully transferred to individual wells in a 24-well plate (Carrier Plate Systems; Thermo Fisher Scientific; 141002) carrying a suspension of GFP-expressing E. coli (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Cells that respond to time-varying chemical gradients established in these reservoirs either migrate toward and attach to the agar pads or are repelled (42, 43). In the primed case, the cell suspension contained 700 μM indole. In the unprimed case, the cell suspension contained no indole. After 5 min, the inserts were carefully removed, gently washed with MB to remove unstuck cells, and then imaged via confocal microscopy. Custom-written MATLAB codes were then employed to count the number of cells adhered to the surface.

Statistical Analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed with the Student’s t test. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data Availability.

All data discussed in this paper are available in the main text and SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Victor Sourjik for discussions. P.P.L. acknowledges support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences United States (R01-GM123085) and the US Department of Defense Army Research Development and Engineering Command Army Research Laboratory (W911NF1810353). Partial support from the Nesbitt Chair endowment to A.J. is also acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.S.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1916974117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chet I., Mitchell R., Ecological aspects of microbial chemotactic behavior. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 30, 221–239 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falke J. J., Bass R. B., Butler S. L., Chervitz S. A., Danielson M. A., The two-component signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis: A molecular view of signal transduction by receptors, kinases, and adaptation enzymes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 457–512 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadhams G. H., Armitage J. P., Making sense of it all: Bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 1024–1037 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matilla M. A., Krell T., The effect of bacterial chemotaxis on host infection and pathogenicity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42, fux052 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler J., Templeton B., The effect of environmental conditions on the motility of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 46, 175–184 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesibov R., Adler J., Chemotaxis toward amino acids in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 112, 315–326 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shioi J., Dang C. V., Taylor B. L., Oxygen as attractant and repellent in bacterial chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 169, 3118–3123 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kihara M., Macnab R. M., Cytoplasmic pH mediates pH taxis and weak-acid repellent taxis of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 145, 1209–1221 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y., Sourjik V., Opposite responses by different chemoreceptors set a tunable preference point in Escherichia coli pH taxis. Mol. Microbiol. 86, 1482–1489 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda K., Imae Y., Shioi J.-I., Oosawa F., Effect of temperature on motility and chemotaxis of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 127, 1039–1046 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulick A., et al. , Mechanism of bidirectional thermotaxis in Escherichia coli. eLife 6, e26607 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopes J. G., Sourjik V., Chemotaxis of Escherichia coli to major hormones and polyamines present in human gut. ISME J. 12, 2736–2747 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeney K. M., Finlay B. B., Enteric pathogen exploitation of the microbiota-generated nutrient environment of the gut. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 92–98 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makki K., Deehan E. C., Walter J., Bäckhed F., The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 23, 705–715 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bansal T., et al. , Differential effects of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and indole on Escherichia coli O157:H7 chemotaxis, colonization, and gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75, 4597–4607 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen S. H., Reader R. W., Kort E. N., Tso W. W., Adler J., Change in direction of flagellar rotation is the basis of the chemotactic response in Escherichia coli. Nature 249, 74–77 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsang N., Macnab R., Koshland D. E. Jr, Common mechanism for repellents and attractants in bacterial chemotaxis. Science 181, 60–63 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tso W. W., Adler J., Negative chemotaxis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 118, 560–576 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domka J., Lee J., Wood T. K., YliH (BssR) and YceP (BssS) regulate Escherichia coli K-12 biofilm formation by influencing cell signaling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2449–2459 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J., Bansal T., Jayaraman A., Bentley W. E., Wood T. K., Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli biofilms are inhibited by 7-hydroxyindole and stimulated by isatin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4100–4109 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J., Attila C., Cirillo S. L., Cirillo J. D., Wood T. K., Indole and 7-hydroxyindole diminish Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Microb. Biotechnol. 2, 75–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikaido E., et al. , Effects of indole on drug resistance and virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium revealed by genome-wide analyses. Gut Pathog. 4, 5 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J. H., Lee J., Indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 426–444 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sridharan G. V., et al. , Prediction and quantification of bioactive microbiota metabolites in the mouse gut. Nat. Commun. 5, 5492 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A., Sperandio V., Indole signaling at the host-microbiota-pathogen interface. MBio 10, e01031-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohli N., et al. , The microbiota metabolite indole inhibits Salmonella virulence: Involvement of the PhoPQ two-component system. PLoS One 13, e0190613 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard M. F., Bina X. R., Bina J. E., Indole inhibits ToxR regulon expression in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 87, e00776-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S.-K., Park H.-Y., Lee J.-H., Anthranilate deteriorates the structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms and antagonizes the biofilm-enhancing indole effect. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2328–2338 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darkoh C., Plants-Paris K., Bishoff D., DuPont H. L., Clostridium difficile modulates the gut microbiota by inducing the production of indole, an interkingdom signaling and antimicrobial molecule. mSystems 4, e00346-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao H., Cremer P. S., Manson M. D., A sensitive, versatile microfluidic assay for bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5449–5454 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Springer M. S., Goy M. F., Adler J., Sensory transduction in Escherichia coli: Two complementary pathways of information processing that involve methylated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 3312–3316 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muskavitch M. A., Kort E. N., Springer M. S., Goy M. F., Adler J., Attraction by repellents: An error in sensory information processing by bacterial mutants. Science 201, 63–65 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkinson J. S., Revello P. T., Sensory adaptation mutants of E. coli. Cell 15, 1221–1230 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montrone M., Oesterhelt D., Marwan W., Phosphorylation-independent bacterial chemoresponses correlate with changes in the cytoplasmic level of fumarate. J. Bacteriol. 178, 6882–6887 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reader R. W., Tso W.-W., Springer M. S., Goy M. F., Adler J., Pleiotropic aspartate taxis and serine taxis mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111, 363–374 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segall J. E., Block S. M., Berg H. C., Temporal comparisons in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 8987–8991 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krikos A., Conley M. P., Boyd A., Berg H. C., Simon M. I., Chimeric chemosensory transducers of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 1326–1330 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chimerel C., Field C. M., Piñero-Fernandez S., Keyser U. F., Summers D. K., Indole prevents Escherichia coli cell division by modulating membrane potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 1590–1594 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zarkan A., et al. , Indole pulse signalling regulates the cytoplasmic pH of E. coli in a memory-like manner. Sci. Rep. 9, 3868 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilks J. C., Slonczewski J. L., pH of the cytoplasm and periplasm of Escherichia coli: Rapid measurement by green fluorescent protein fluorimetry. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5601–5607 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez K. A., II, et al. , Cytoplasmic pH response to acid stress in individual cells of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis observed by fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 3706–3714 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jani S., Seely A. L., Peabody V G. L., Jayaraman A., Manson M. D., Chemotaxis to self-generated AI-2 promotes biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 163, 1778–1790 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jani S., “Visualizing chemoattraction of planktonic cells to a biofilm” in Bacterial Chemosensing, Manson M., Ed. (Methods in Molecular Biology, Humana Press, New York, NY, 2018), vol. 1729, pp. 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berg H. C., The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 19–54 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lele P. P., Berg H. C., Switching of bacterial flagellar motors [corrected] triggered by mutant FliG. Biophys. J. 108, 1275–1280 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minamino T., et al. , Structural insight into the rotational switching mechanism of the bacterial flagellar motor. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000616 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lele P. P., Shrivastava A., Roland T., Berg H. C., Response thresholds in bacterial chemotaxis. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500299 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cluzel P., Surette M., Leibler S., An ultrasensitive bacterial motor revealed by monitoring signaling proteins in single cells. Science 287, 1652–1655 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan J., Branch R. W., Hosu B. G., Berg H. C., Adaptation at the output of the chemotaxis signalling pathway. Nature 484, 233–236 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eisenbach M., Constantinou C., Aloni H., Shinitzky M., Repellents for Escherichia coli operate neither by changing membrane fluidity nor by being sensed by periplasmic receptors during chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 172, 5218–5224 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lai R. Z., et al. , Cooperative signaling among bacterial chemoreceptors. Biochemistry 44, 14298–14307 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Togashi F., Yamaguchi S., Kihara M., Aizawa S. I., Macnab R. M., An extreme clockwise switch bias mutation in fliG of Salmonella typhimurium and its suppression by slow-motile mutations in motA and motB. J. Bacteriol. 179, 2994–3003 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khan S., Macnab R. M., Proton chemical potential, proton electrical potential and bacterial motility. J. Mol. Biol. 138, 599–614 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan S., Spudich J. L., McCray J. A., Trentham D. R., Chemotactic signal integration in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9757–9761 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan S., Trentham D. R., Biphasic excitation by leucine in Escherichia coli chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 186, 588–592 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darkoh C., Chappell C., Gonzales C., Okhuysen P., A rapid and specific method for the detection of indole in complex biological samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 8093–8097 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lozupone C., et al. , Identifying genomic and metabolic features that can underlie early successional and opportunistic lifestyles of human gut symbionts. Genome Res. 22, 1974–1984 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moreira C. G., et al. , Bacterial adrenergic sensors regulate virulence of enteric pathogens in the gut. MBio 7, e00826-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parkinson J. S., Houts S. E., Isolation and behavior of Escherichia coli deletion mutants lacking chemotaxis functions. J. Bacteriol. 151, 106–113 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L., One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scharf B. E., Fahrner K. A., Turner L., Berg H. C., Control of direction of flagellar rotation in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 201–206 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ford K. M., Chawla R., Lele P. P., Biophysical characterization of flagellar motor functions. J. Vis. Exp. (119, e55240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lele P. P., Branch R. W., Nathan V. S., Berg H. C., Mechanism for adaptive remodeling of the bacterial flagellar switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 20018–20022 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hegde M., et al. , Chemotaxis to the quorum-sensing signal AI-2 requires the Tsr chemoreceptor and the periplasmic LsrB AI-2-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 193, 768–773 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hansen M. C., Palmer R. J. Jr, Udsen C., White D. C., Molin S., Assessment of GFP fluorescence in cells of Streptococcus gordonii under conditions of low pH and low oxygen concentration. Microbiology 147, 1383–1391 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data discussed in this paper are available in the main text and SI Appendix.