Significance

The “σ-finger” of bacterial initiation factor σ binds within RNA polymerase active-center cleft and blocks the path of nascent RNA. It has been hypothesized that the σ-finger must be displaced during initial transcription. By determining crystal structures defining successive steps in initial transcription, we demonstrate that the σ-finger is displaced in a stepwise fashion, driven by collision with the RNA 5′-end, as nascent RNA is extended from ∼5 nt to ∼10 nt during initial transcription. We further show that this is true for both the primary σ-factor and alternative σ-factors, and that the nascent RNA length at which displacement occurs is determined by the extent to which the σ-finger penetrates the active center of RNA polymerase.

Keywords: transcription initiation, initial transcription, promoter escape, sigma factor, initiation factor

Abstract

All organisms—bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes—have a transcription initiation factor that contains a structural module that binds within the RNA polymerase (RNAP) active-center cleft and interacts with template-strand single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) in the immediate vicinity of the RNAP active center. This transcription initiation-factor structural module preorganizes template-strand ssDNA to engage the RNAP active center, thereby facilitating binding of initiating nucleotides and enabling transcription initiation from initiating mononucleotides. However, this transcription initiation-factor structural module occupies the path of nascent RNA and thus presumably must be displaced before or during initial transcription. Here, we report four sets of crystal structures of bacterial initially transcribing complexes that demonstrate and define details of stepwise, RNA-extension-driven displacement of the “σ-finger” of the bacterial transcription initiation factor σ. The structures reveal that—for both the primary σ-factor and extracytoplasmic (ECF) σ-factors, and for both 5′-triphosphate RNA and 5′-hydroxy RNA—the “σ-finger” is displaced in stepwise fashion, progressively folding back upon itself, driven by collision with the RNA 5′-end, upon extension of nascent RNA from ∼5 nt to ∼10 nt.

All cellular RNA polymerases (RNAPs)—bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic—require a transcription initiation factor, or a set of transcription initiation factors, to perform promoter-specific transcription initiation (1–4). In all promoter-specific transcription initiation complexes—bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic—a structural module of a transcription initiation factor enters the RNAP active-center cleft and interacts with template-strand single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) close to the RNAP active center (2, 5–27). Deletion of the structural module results in severely impaired transcription activity (6–9, 28, 29). This transcription initiation-factor structural module preorganizes template-strand ssDNA to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center, thereby facilitating binding of initiating nucleotides and enabling primer-independent transcription initiation from initiating mononucleotides (1–9, 11, 12, 16–19, 24, 27–29). However, this transcription initiation-factor structural module occupies the path that will be occupied by nascent RNA during initial transcription and thus presumably must be displaced before or during initial transcription (1–3, 5–12, 17, 18, 28, 30–33).

In bacterial transcription initiation complexes containing the primary σ-factor and most alternative σ-factors, the relevant structural module is the σ-factor “σ-finger” (also referred to as σR3.2, σR3-σR4 linker, or the σR2-σR4 linker) (1, 2, 5–10, 14, 34). In bacterial transcription initiation complexes containing the alternative σ-factor, σ54, the relevant structural module is the σ54 RII.3 region, which is structurally unrelated to the σ-finger (13, 15). In archaeal RNAP-, eukaryotic RNAP-I-, eukaryotic RNAP-II-, and eukaryotic RNAP-III-dependent transcription initiation complexes, the relevant structural modules are the TFB zinc ribbon and CSB, the Rrn7 zinc ribbon and B-reader, the TFIIB zinc ribbon and B-reader, and the Brf1 zinc ribbon, respectively, all of which are structurally related to each other but are structurally unrelated to the bacterial σ-finger and σ54 RII.3 (16–18, 21–27).

It has been apparent for nearly two decades that the relevant structural module must be displaced before or during initial transcription (1–3, 5–12, 17, 18, 28–33). Changes in protein-DNA photo-crosslinking suggestive of displacement have been reported (1), and changes in profiles of abortive initiation and initial-transcription pausing upon mutation of the relevant structural module, have been reported (1, 9, 24, 28, 29, 31–33, 35, 36). However, the displacement has not been observed directly. As a result, it has remained unclear whether the displacement occurs in a single step or in multiple steps, where the displaced residues move, and what drives the displacement.

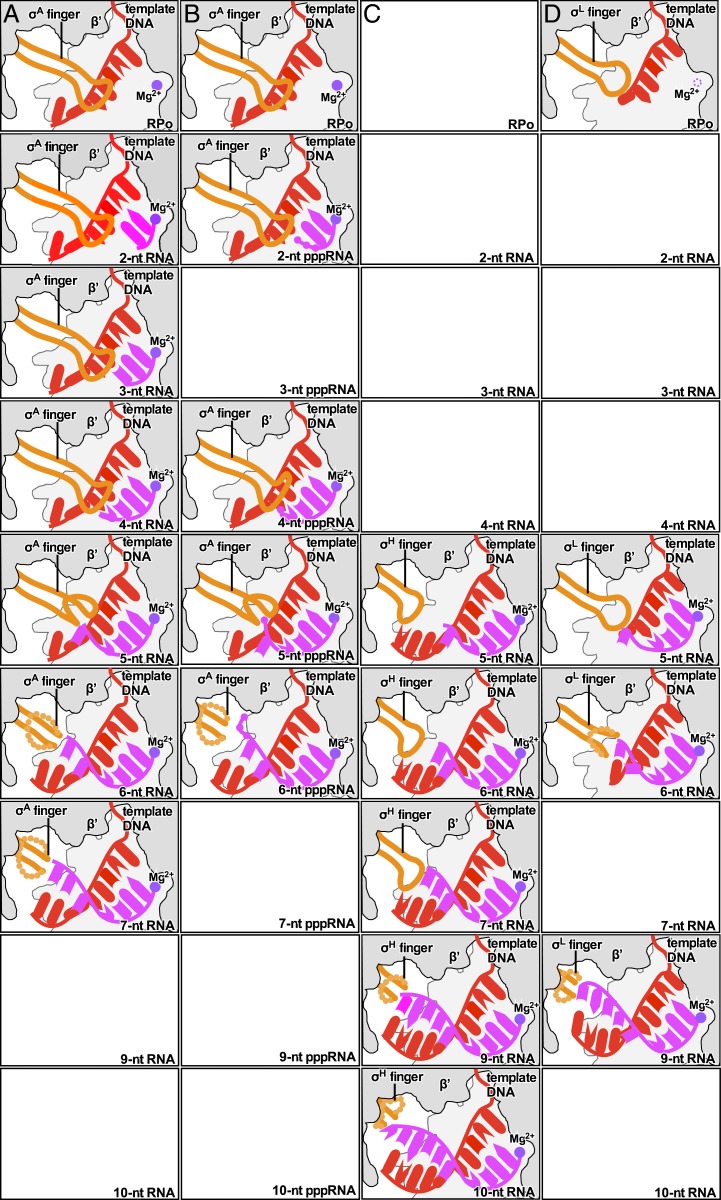

Here, we present four sets of crystal structures of bacterial initially transcribing complexes that demonstrate—and define structural and mechanistic details of—displacement of the σ-finger during initial transcription. The first and second sets are structures of initial transcribing complexes comprising Thermus thermophilus (Tth) RNAP, the Tth primary σ-factor, σA, promoter DNA, and either 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNAs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 nt in length (σA-RPitc2, σA-RPitc3, σA-RPitc4, σA-RPitc5, σA-RPitc6, and σA-RPitc7; Fig. 1) or comprising Tth RNAP, Tth σA, promoter DNA, and 5′-triphosphate-containing RNAs, 2, 4, 5, and 6 nt in length (σA-RPitc2-PPP, σA-RPitc4-PPP, σA-RPitc5-PPP, and σA-RPitc6-PPP; Fig. 2). These sets correspond to, respectively, six successive intermediates in primary σ-factor-dependent, primer-dependent transcription initiation (5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA; ref. 2), and four successive intermediates in primary σ-factor-dependent, primer-independent transcription initiation (5-triphosphate-containing RNA; ref. 2). The third and fourth sets are structures of initial transcribing complexes comprising Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) RNAP, Mtb extracytoplasmic-function (ECF) σ-factor σH, promoter DNA, and 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA oligomers 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10 nt in length (σH-RPitc5, σH-RPitc6, σH-RPitc7, σH-RPitc9, and σH-RPitc10; Fig. 3) and comprising Mtb RNAP, Mtb ECF σ-factor σL, promoter DNA, and 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA oligomers 5, 6, and 9 nt in length (σL-RPitc5, σL-RPitc6, and σL-RPitc9; Fig. 4). These sets correspond to, respectively, five intermediates in alternative σ-factor-dependent transcription initiation with ECF σ-factor σH, and three intermediates in alternative σ-factor-dependent transcription initiation with ECF σ-factor σL. Taken together, the structures establish that—for both the primary σ-factor and ECF σ-factors, and for both 5′-hydroxyl RNA and 5′-triphosphate RNA—the σ-finger is displaced in stepwise fashion, progressively folding back upon itself, driven by collision with the RNA 5′-end, upon extension of nascent RNA from ∼5 nt to ∼10 nt.

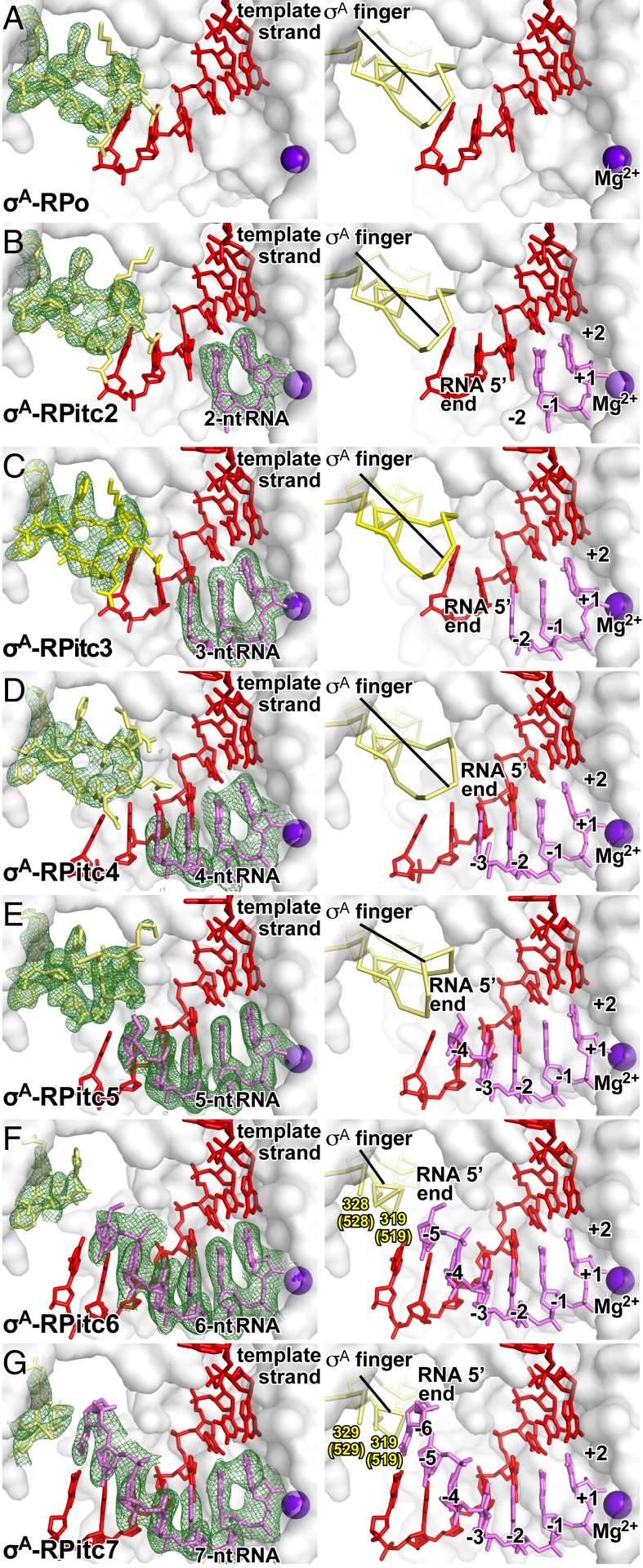

Fig. 1.

Stepwise, RNA-driven displacement of the σ-finger: primary σ-factor, 5′-hydroxyl RNA. Crystal structures of (A) σA-RPo (PDB 4G7H; ref. 5), (B) σA-RPitc2 (PDB 4G7O; ref. 5), (C) σA-RPitc3 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S2), (D) σA-RPitc4 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S2), (E) σA-RPitc5 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S2), (F) σA-RPitc6 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S2), and (G) σA-RPitc7 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S2). Left subpanels, electron-density map and atomic model. Right subpanels, atomic model. Green mesh, simulated-annealing Fo-Fc electron-density map contoured at 2.5 σ; gray surface, RNAP β′ subunit; yellow sticks, σ-finger; red sticks, template-strand DNA; pink sticks, RNA; purple sphere, catalytic Mg2+ ion.

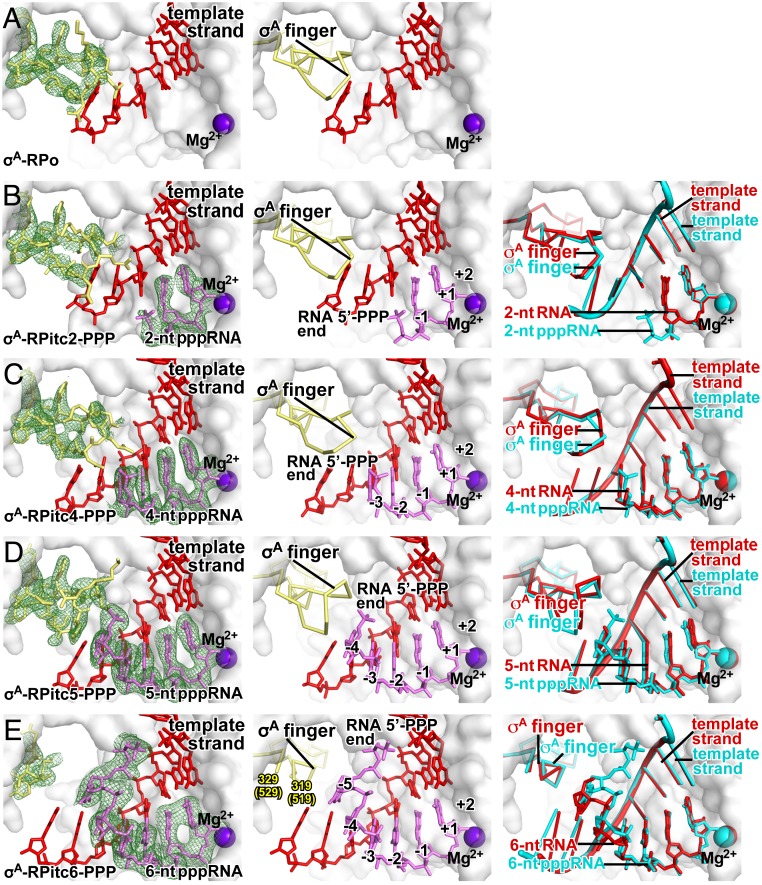

Fig. 2.

Stepwise, RNA-driven displacement of the σ-finger: primary σ-factor, 5′-triphosphate RNA. Crystal structures of (A) σA-RPo (PDB 4G7H; ref. 5), (B) σA-RPitc2-PPP (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S3), (C) σA-RPitc4-PPP (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S3), (D) σA-RPitc5-PPP (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S3), and (E) σA-RPitc6-PPP (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S3). Left subpanels, electron-density map and atomic model (colors and contours as in Fig. 1). Center subpanels, atomic model (colors as in Fig. 1). Right subpanel, superimposition of structures of corresponding complexes with 5′-hydroxyl RNA (cyan and gray) and 5′-triphosphate RNA (red and gray).

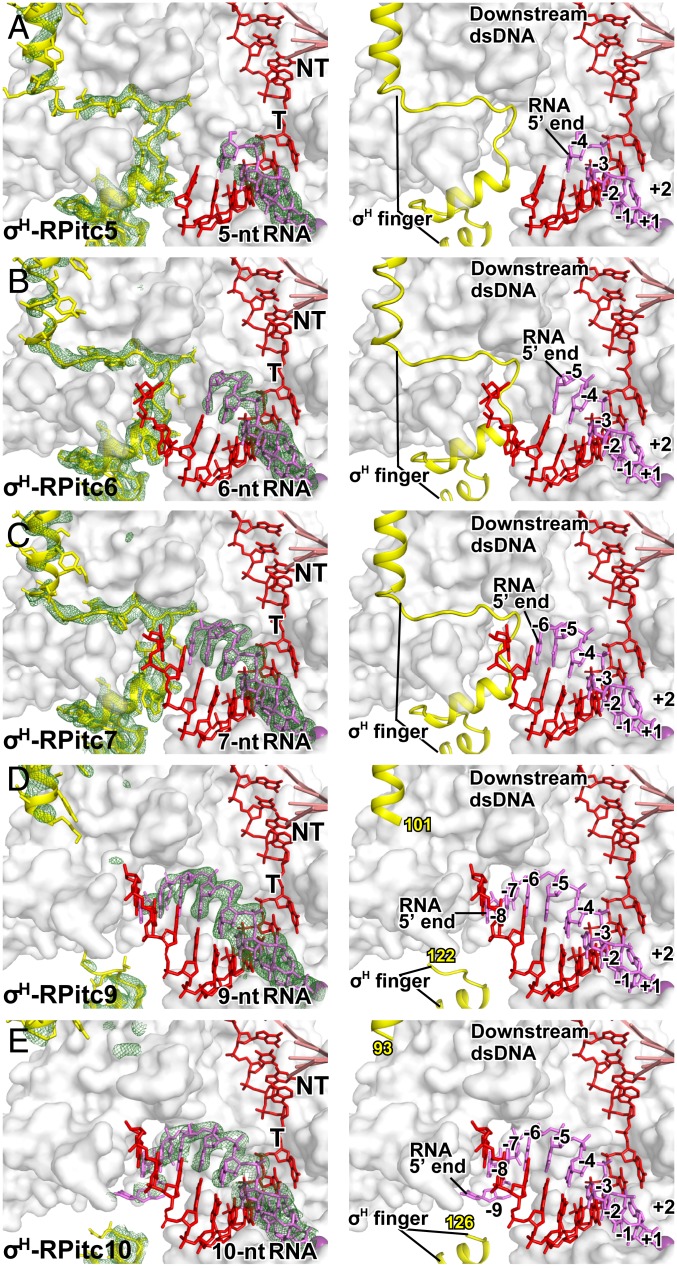

Fig. 3.

Stepwise, RNA-driven displacement of the σ-finger: ECF σ-factor σH. Crystal structures of (A) σH-RPitc5 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S4), (B) σH-RPitc6 (PDB 6JCX; ref. 6), (C) σH-RPitc7 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S4), (D) σH-RPitc9 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S4), and (E) σH-RPitc10 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S4). Colors and contours as in Fig. 1.

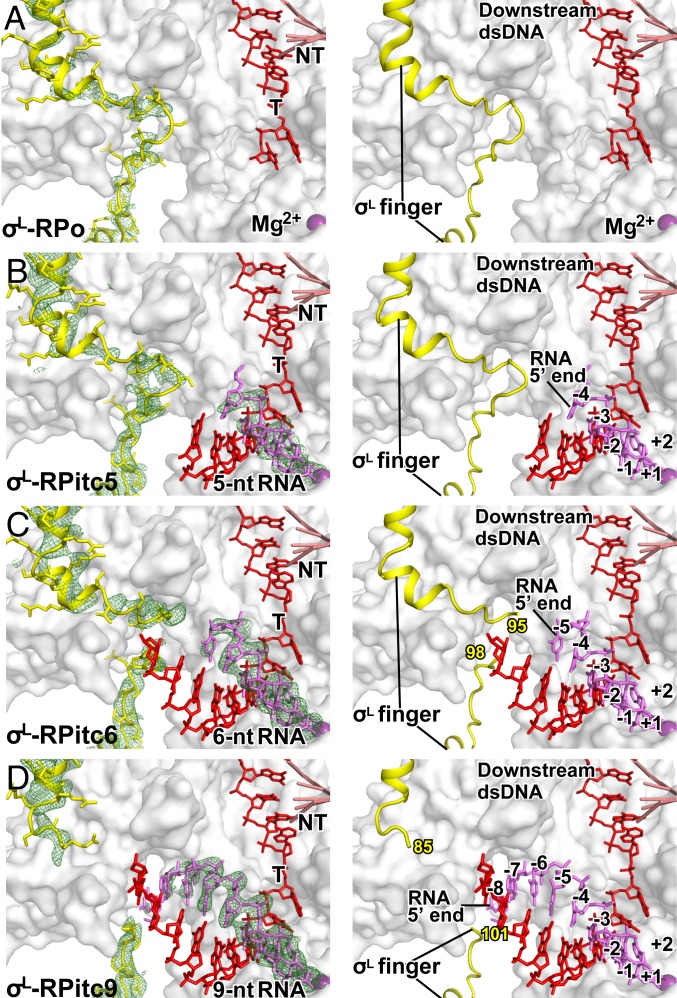

Fig. 4.

Stepwise, RNA-driven displacement of the σ-finger: ECF σ-factor σL. Crystal structures of (A) σL-RPo (PDB 6DVE; ref. 7), (B) σL-RPitc5, (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S5; ref. 7), (C) σL-RPitc6 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S5), and (D) σL-RPitc9 (this work; see SI Appendix, Table S5). Colors and contours as in Fig. 1.

Results

Stepwise, RNA-Driven Displacement of the σ-Finger: Primary σ, 5′-Hydroxyl RNA.

The primary σ-factor, responsible for transcription initiation at most promoters under most conditions, is σA (σ70 in Escherichia coli; ref. 1). The σ-finger of σA (residues 507 to 520; σA residues numbered as in E. coli σ70 here and hereafter) contacts template-strand ssDNA nucleotides at positions −4 to −3 and preorganizes template-strand ssDNA to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center (5, 11, 12). In a crystal structure of an RNAP-promoter open complex containing a derivative of σA that lacks the σ-finger residues that contact template-strand ssDNA, template-strand ssDNA is completely disordered, [Tth (Δ'513'-'519')σA-RPo; see SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S1], graphically confirming the functional role of the σ-finger in preorganizing template-strand ssDNA.

Transcription initiation can proceed through either a primer-dependent pathway or a primer-independent pathway (2). In primer-dependent transcription initiation, which typically occurs and plays an important role during stationary growth phase (37, 38), the initiating entity is a short RNA oligomer, typically a 5′-hydroxyl-containing short RNA oligomer, which yields a nascent RNA product containing a 5′-hydroxyl end.

To define the structural and mechanistic details of displacement of the σ-finger during primary σ-factor-dependent, primer-dependent transcription initiation, we determined crystal structures of initial transcribing complexes comprising Tth RNAP, the Tth primary σ-factor, σA, promoter DNA, and 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNAs 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 nt in length (Tth σA-RPitc3, σA-RPitc4, σA-RPitc5, σA-RPitc6, and σA-RPitc7; Fig. 1 C–G and see SI Appendix, Fig. S1A and Table S2). In each case, the partial transcription bubble in the structure is superimposable on the corresponding parts of the transcription bubbles in published structures of complexes with full transcription bubbles (12, 39, 40). In each case, the crystal structure shows a posttranslocated transcription initiation complex (2), in which the RNA oligomer forms a base-paired RNA-DNA hybrid with template-strand DNA and is positioned such that the RNA 3′ nucleotide is located in the RNAP active-center product site (P site), in an orientation that would allow binding of, and base stacking by, an NTP substrate in the RNAP active-center addition site (A site) (Fig. 1 and see SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Thus, in Tth σA-RPitc3, σA-RPitc4, σA-RPitc5, σA-RPitc6, and σA-RPitc7, the RNA oligomers are base paired with template-strand DNA positions −2 to +1, −3 to +1, −4 to +1, −5 to +1, and −6 to +1, respectively (Fig. 1 C–G). Together with the previously reported crystal structures of Tth σA-RPo and σA-RPitc2 (PDB 4G7H and PDB 4G7O; ref. 5), the new crystal structures constitute a series of structures in which the position of the RNA 5′-end relative to RNAP varies in single-nucleotide increments, and in which the position of RNA 3′-end relative to RNAP remains constant, as in stepwise RNA extension in initial transcription (Fig. 1).

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc3, the σ-finger adopts the same conformation as in the previously reported structures of Tth σA-RPo and σA-RPitc2 (Fig. 1 A–C and ref. 5). Residues D514, D516, S517, and F522 of the σA finger make H-bonded and van der Waals interactions with the template-strand DNA nucleotides at positions −3, −4, and −5, preorganizing the template strand to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C).

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc4, the σ-finger adopts the same conformation as in the structures of Tth σA-RPo, σA-RPitc2, and σA-RPitc3 (Fig. 1 A–D), and residues D514, S517, and F522 of the σA finger again make H-bonded and van der Waals interactions with the template-strand DNA nucleotides at positions −3, −4, and −5, preorganizing the template strand to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). However, in RPitc4, residues D513 and D514 of the σA finger now also make H-bonded and van der Waals interactions with RNA, contacting RNA nucleotides at positions −3 and −4 in a manner that likely stabilizes the RNA-DNA hybrid in σA-RPitc4.

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc5, the σ-finger adopts a different conformation as compared to the structures of Tth σA-RPo, σA-RPitc2, σA-RPitc3, and σA-RPitc4 (Fig. 1 A–E), and this difference in conformation coincides with, and likely is driven by, the movement of the 5′-end of RNA into the position previously occupied by the tip of the σ-finger and resulting steric collision between the RNA and the σ-finger (Fig. 1 D and E). In σA-RPitc5, as compared to in σA-RPo and σA-RPitc2 through σA-RPitc4, the tip of the σA finger—σ-residues 513, 514, and 515—folds back over the rest of the σ-finger, resulting in the displacement, away from the RNAP active center, of the Cα atoms of residues 513, 514, and 515 by 3 Å, 6 Å, and 3 Å, respectively (Fig. 1 D and E). The change in conformation can be best understood as the folding of the loop of the σ-finger β-hairpin back over the strands of the σ-finger β-hairpin (Fig. 1 D and E). In this conformation, the σ-finger makes interactions with the RNA-DNA hybrid, with σ-residues I511 and F522 making van del Waals interactions with template-strand DNA at position −5, and with σ-residues D513 and D516 making H bonds with RNA at position −4.

In the crystal structures of Tth σA-RPitc6 and σA-RPitc7, the σ-finger again adopts different conformations, and the differences in conformation again coincide with, and likely are driven by, movement of the 5′-end of RNA into the positions previously occupied by the tip of the σ-finger and resulting steric collision between the RNA and the σ-finger (Fig. 1 F and G). In the structure of σA-RPitc6, eight residues of the σA finger—σ-residues 520 to 527—exhibit segmental disorder, indicating that this eight-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 1F). In the structure of σA-RPitc7, nine residues of the σA finger—σ-residues 520 to 528—exhibit segmental disorder, indicating that this nine-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 1G). We interpret the changes in conformation from σA-RPitc5 to σA-RPitc6 to σA-RPitc7 as successive further displacements of the loop of the σ-finger β-hairpin—involving displacement of first an eight-residue segment and then a nine-residue segment—back over the strands of the σ-finger β-hairpin, accompanied by increased flexibility of the displaced segments (Fig. 1 E–G).

Taken together, the crystal structures of Tth σA-RPo, σA-RPitc2, σA-RPitc3, σA-RPitc4, σA-RPitc5, σA-RPitc6, and σA-RPitc7 demonstrate that nascent RNA with a 5′-hydroxyl end displaces the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor in a stepwise fashion, starting upon extension of nascent RNA to a length of 5 nt and continuing upon further extension through a length of at least 7 nt (Fig. 1).

Stepwise, RNA-Driven Displacement of the σ-Finger: Primary σ-Factor, 5′-Triphosphate RNA.

As noted above, transcription initiation can proceed through either a primer-dependent pathway or a primer-independent pathway (2). In primer-independent transcription initiation, the initiating entity is a mononucleotide, typically a nucleoside triphosphate (NTP), which yields a nascent RNA product containing a 5′-triphosphate end. As compared to the 5′-hydroxyl end typically generated in primer-dependent initiation, the 5′-triphosphate end typically generated in primer-independent initiation has greater charge (−4 charge vs. 0 charge) and greater steric bulk (∼160 Å3 solvent-accessible volume vs. ∼7 Å3 solvent-accessible volume). In an RNA-extension-driven displacement mechanism, the additional charge and steric bulk in principle could change the length dependence or, even the pathway, of initiation-factor displacement. To assess whether the additional charge and steric bulk in fact change the length dependence or pathway of initiation-factor displacement, we performed an analysis analogous to that in the preceding section, but assessing nascent RNA products containing 5′-triphosphate ends.

We determined crystal structures of initial transcribing complexes comprising Tth RNAP, the Tth primary σ-factor, σA, promoter DNA, and 5′-triphosphate-containing RNAs 2, 4, 5, and 6 nt in length (Tth σA-RPitc2-PPP, σA-RPitc4-PPP, σA-RPitc5-PPP, and σA-RPitc6-PPP; Fig. 2 B–E and see SI Appendix, Fig. S1B and Table S3). In each case, the crystal structure shows a posttranslocated transcription initiation complex, in which the RNA oligomer forms a base-paired RNA-DNA hybrid with template-strand DNA and is positioned such that the RNA 3′-nucleotide is located in the RNAP active-center P site, in an orientation that would allow binding of, and base stacking by, an NTP substrate in the RNAP active-center A site. Thus, in Tth σA-RPitc2-PPP, σA-RPitc4-PPP, σA-RPitc5-PPP, and σA-RPitc6-PPP, the RNA oligomers are base paired with template-strand DNA positions −1 to +1, −3 to +1, −4 to +1, and −5 to +1, respectively (Fig. 2 B–E). Together with the previously reported crystal structure of Tth σA-RPo (PDB 4G7H; refs. 5 and 41), the crystal structures constitute a nearly complete series of structures in which the position of the RNA 5′-end relative to RNAP varies in single-nucleotide increments, and in which the position of the RNA 3′-end relative to RNAP remains constant, as in stepwise RNA extension in initial transcription (Fig. 2). Efforts were made to obtain corresponding crystal structures of complexes containing 5′-triphosphate-containing RNAs 3 nt and 7 nt in length, but these efforts were unsuccessful, instead yielding a structure of a fractionally translocated complex (42, 43) and a structure with a disordered RNA 5′-end, respectively.

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc2-PPP, the σ-finger adopts the same conformation as in the structures of Tth σA-RPo (PDB 4G7H; Fig. 2 A and B). As in RPo, residues D514, D516, S517, and F522 of the σA finger make H-bonded and van der Waals interactions with the template-strand DNA nucleotides at positions−3 and −4 in a manner that preorganizes the template strand to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). The RNAP β-subunit residue R687 (RNAP residues numbered as in E. coli RNAP here and hereafter) makes an H-bonded interaction with the α-phosphate of the RNA 5′-triphosphate; and the template-strand DNA nucleotide at positions −2 makes an H-bonded interaction with the γ-phosphate of the RNA 5′-triphosphate.

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc4-PPP, the σ-finger adopts the same conformation as in the structures of Tth σA-RPo and σA-RPitc2-PPP (Fig. 2 A–C). Essentially as in σA-RPo and σA-RPitc2-PPP, residues D514, I511, and F522 of the σA finger make van der Waals interactions with the template-strand DNA nucleotides at positions −3, −4, and −5 in a manner that preorganizes the template strand to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center (Fig. 2 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C); and, as in the structure of Tth σA-RPitc4, residue D514 of the σA finger makes H-bonded and van der Waals interactions with RNA, contacting RNA nucleotides at positions −2 and −3 in a manner that likely stabilizes the RNA-DNA hybrid. RNAP β-subunit residue R540 makes a salt bridge with the α-phosphate of the RNA 5′-triphosphate, and RNAP β-subunit residue N568 makes an H-bonded interaction with the α-phosphate of the RNA 5′-triphosphate. The β- and γ-phosphates of the RNA 5′-triphosphate are disordered, suggesting that the β- and γ-phosphates do not adopt a defined conformation and do not make defined interactions (Fig. 2A). We point out that Steitz and coworkers have reported close proximity, and likely contact, between the σ-finger and the RNA 5′-end in a low-resolution (∼5.5-Å resolution) crystal structure of an initial transcribing complex containing a 5′-triphosphate-containing 5-nt RNA product in a pretranslocated state (12). The position of the RNA 5′-end in our structure of σA-RPitc4-PPP in a posttranslocated state corresponds to the position of the RNA 5′-end in their structure, and, in our structure, contacts between the σ-finger and the RNA 5′-end are resolved and defined.

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc5-PPP, the σ-finger adopts a conformation that is different from the conformation in the structures of Tth RPo, Tth RPitc2-PPP, and RPitc4-PPP (Fig. 2 A–D) and that is similar to the conformation in the structure of Tth σA-RPitc5 (Figs. 1E and 2D). As described above for the difference in conformation between σA-RPitc4 and σA-RPitc5, the difference in conformation between σA-RPitc4-PPP and σA-RPitc5-PPP coincides with, and likely is driven by, movement of the 5′-end of RNA into the position previously occupied by the tip of the σ-finger and resulting steric collision between the RNA and the σ-finger (Figs. 1 D and E and 2 C and D). The loop of the σ-finger β-hairpin folds back over the strands of the σ-finger β-hairpin (Fig. 2D), and, in this conformation, the σ-finger makes interactions with the RNA-DNA hybrid, with σ-residues I511 and F522 making van del Waals interactions with template-strand DNA at position −5, and with σ-residues D516 making H bonds with RNA at position −4 (Fig. 2D). RNAP β-subunit residue R540 makes a salt bridge with the α-phosphate of the RNA 5′-triphosphate. The β- and γ-phosphates of the RNA 5′-triphosphate are disordered, suggesting that the β- and γ-phosphates do not adopt a defined conformation and do not make defined interactions (Fig. 2C). We note that the negatively charged RNA 5′-triphosphate (−4 charge) is located close to—∼3 Å—the negatively charged tip of the σA finger (−3 charge), and that this proximity between negatively charged groups must result in electrostatic repulsion. This electrostatic repulsion does not manifest itself as a difference in conformation between σA-RPitc5-PPPand Tth σA-RPitc5 (Figs. 1E and 2D), but could manifest itself as a difference in kinetics of RNA extension for 5′-triphosphate-containing nascent RNA products vs. 5′-hydoxyl-containing nascent RNA products, possibly accounting for previously observed differences in abortive-product distributions (2) and differences in susceptibilities to initial-transcription pausing (33) for 5′-triphosphate-containing nascent RNA products vs. 5′-hydoxyl-containing nascent RNA products. We point out that Murakami and coworkers have reported disorder of part of the σ-finger in a crystal structure of an initial transcribing complex containing a 5′-triphosphate-containing 6-nt RNA product in a pretranslocated state (11). The position of the RNA 5′-end in our structure of σA-RPitc5-PPP in a posttranslocated state corresponds to the position of the RNA 5′-end in their structure, but, in our structure, the conformation of the full σ-finger is defined.

In the crystal structure of Tth σA-RPitc6-PPP, the σ-finger adopts a conformation that is even more different from the conformation in the structure of Tth RPitc4-PPP (Fig. 2 C–E) and that is similar to the conformation in the structure of Tth σA-RPitc6 (Figs. 1F and 2E). In the structure of σA-RPitc6-PPP, nine residues of the σA finger—σ-residues 520 to 528—exhibit segmental disorder, indicating that this nine-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 2E). We interpret the successive changes in conformation from σA-RPitc4-PPP to σA-RPitc5-PPP to σA-RPitc6-PPP as successive displacements of the loop of the σ-finger β-hairpin back over the strands of the σ-finger β-hairpin, accompanied by increases in flexibility of the displaced segment (Fig. 2 C–E). In the structure of σA-RPitc6-PPP, RNAP β′-subunit residue K334 makes a salt bridge with the β-phosphate of the RNA 5′-triphosphate. The α- and γ-phosphates of the RNA 5′-triphosphate are ordered but make no interactions with RNAP and σ.

Taken together, the crystal structures of Tth σA-RPo, σA-RPitc2-PPP, σA-RPitc4-PPP, σA-RPitc5-PPP, and σA-RPitc6-PPP demonstrate that nascent RNA with a 5′-triphosphate end—like nascent RNA with a 5′-hydroxyl end—displaces the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor in a stepwise fashion, starting upon extension of nascent RNA to a length of 5 nt and continuing upon further extension through a length of at least 6 nt (Fig. 2).

Stepwise, RNA-Driven Displacement of the σ-Finger: ECF σ-Factor σH.

The largest and most functionally diverse class of alternative σ-factors is the ECF class (1, 44–47). ECF σ-factors consist of a structural module (σ2) that recognizes a promoter −10 element, a structural module (σ4) that recognizes a promoter −35 element, and a σ-finger (σ2-σ4 linker) that enters the RNAP active-center cleft and interacts with template-strand ssDNA (6–8, 48, 49). However, the σ-fingers of ECF σ-factors are only functional analogs—not also structural homologs—of the σ-fingers of primary σ-factors (1, 6). The σ-fingers of ECF σ-factors are typically shorter than, and are unrelated in sequence to, the σ-fingers of primary σ-factors (6–8); their N- and C-terminal segments exhibit structures similar to those of primary σ-factors, but their central loop regions exhibit structures different from those of primary σ-factors (6–8). As a first step to assess whether the difference in σ-finger length and sequence for ECF σ-factors vs. primary σ-factors affects the mechanism of initiation-factor displacement, we have performed an analysis analogous to that in Fig. 1, but assessing ECF σ-factor-dependent, primer-dependent transcription initiation by Mtb RNAP holoenzyme containing the ECF σ-factor σH, which has a σ-finger that reaches substantially less deeply—∼9 Å less deeply—into the RNAP active-center cleft than the σ-finger of a primary σ-factor (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and refs. 6–8).

In previous work, one of our laboratories determined a crystal structure of a posttranslocated-state initial transcribing complex comprising Mtb RNAP, the Mtb ECF σ-factor σH, promoter DNA, and a 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA 6 nt in length (Mtb σH-RPitc6; PDB 6JCX; ref. 6). Here, we determined crystal structures of posttranslocated-state initial transcribing complexes containing 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNAs 5, 7, 9, and 10 nt in length (Mtb σH-RPitc5, σH-RPitc7, σH-RPitc9, and σH-RPitc10; Fig. 3 A and C–E and see SI Appendix, Fig. S1C and Table S4). (We also attempted to determine a crystal structure of the corresponding complex containing a 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA 8 nt in length, but this attempt was unsuccessful, instead yielding a structure of a pretranslocated-state complex.) Together with the published structure of Mtb σH-RPitc6, the structures provide a series of structures in which the position of the RNA 5′-end relative to RNAP varies, and in which the position of RNA 3′-end relative to RNAP remains constant, as in RNA extension in initial transcription (Fig. 3).

In the crystal structures of Mtb σH-RPitc5, σH-RPitc6, and σH-RPitc7, the conformations of the σH finger are essentially identical (Fig. 3 A–C). At least one of residues T106, T110, W112, and Q113 of the σH finger make H-bonded or van der Waals interactions with the template-strand DNA nucleotides at positions −6 and −7, preorganizing the template strand to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center. In σH-RPitc5 and σH-RPitc6, there are no direct contacts between σH finger and the RNA. In σH-RPitc7, there are direct contacts between the σH finger and the RNA 5′-end, with σH finger residues E107, Q108, and T110 contacting RNA nucleotides at positions −6 in a manner that likely stabilizes the RNA-DNA hybrid.

In contrast, in the crystal structures of Mtb σH-RPitc9 and σH-RPitc10, the σH finger adopts different conformations as compared to the structures of Mtb σH-RPitc5, σH-RPitc6, and σH-RPitc7 (Fig. 3 A–E), and the differences in conformation coincide with, and appear to be driven by, the movement of the 5′-end of RNA into the positions previously occupied by the tip of the σ-finger and resulting steric collision between the RNA and the σ-finger (Fig. 3 A–E). In the structure of σH-RPitc9, a segment comprising 20 residues of the σH finger—σH residues 102 to 121—exhibits segmental disorder, indicating that this 20-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 3D). In the structure of σH-RPitc10, a segment comprising 32 residues of the σH finger—σ-residues 94 to 125—exhibits segmental disorder, indicating that this 32-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 3E). Like the changes in conformation of the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor described in the preceding sections, the change in conformation of the σH finger can be understood as the folding of the loop of the σ-finger hairpin back over the strands of the σ-finger hairpin (Fig. 3 A–E). We thus interpret the changes in conformation from σH-RPitc7 to σH-RPitc9 to σH-RPitc10 as successive displacements of the loop of the σ-finger hairpin—involving displacement of first a 20-residue segment and then a 32-residue segment—back over the strands of the σ-finger hairpin, accompanied by increased flexibility of the displaced segments (Fig. 3 A–E).

Taken together, the crystal structures of Mtb σH-RPitc5, σH-RPitc6, σH-RPitc7, σH-RPitc9, and σH-RPitc10 suggest that nascent RNA with a 5′-hydroxyl end displaces the σ-finger of ECF σ-factor σH in a stepwise fashion, starting upon extension of nascent RNA to a length of 8 or 9 nt and continuing upon further extension through a length of at least 10 nt (Fig. 5C). We conclude that the mechanism of initiation-factor displacement for ECF σ-factor σH is fundamentally similar to the mechanism of initiation-factor displacement for the primary σ-factor, and we suggest that the later start of the process with ECF σ-factor σH than with the primary σ-factor—displacement starting at an RNA length of 8 or 9 nt vs. displacement starting at an RNA length of 5 nt—is a consequence of the fact that the σ-finger of σH finger reaches substantially less deeply—∼9 Å less deeply—into the RNAP active-center cleft than the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B)

Fig. 5.

Summary. Schematic illustration of stepwise, RNA-driven displacement of σ-finger with (A) primary σ-factor in primer-dependent transcription initiation (Fig. 1), (B) primary σ-factor in primer-independent transcription initiation (Fig. 2), (C) ECF σ-factor σH (Fig. 3), and (D) ECF σ-factor σL (Fig. 4). Colors as in Fig. 1. Disordered σ-finger segments are shown as dotted orange line and disordered 5′-triphosphate RNA phosphates are omitted.

Stepwise, RNA-Driven Displacement of the σ-Finger: ECF σ-Factor σL.

The σ-fingers of different ECF σ-factors vary in length and sequence (6). As a second step to assess whether the difference in σ-finger length and sequence for ECF σ-factors vs. primary σ-factors affects the mechanism of initiation-factor displacement, we have performed an analysis analogous to that in Fig. 1, but assessing ECF σ-factor-dependent, primer-dependent transcription initiation by Mtb RNAP holoenzyme containing the ECF σ-factor, σL, which has a σ-finger that reaches slightly less deeply—∼5 Å less deeply—into the RNAP active-center cleft than the σ-finger of a primary σ-factor (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C and ref. 7).

In previous work, one of our laboratories determined crystal structures of a transcription initiation complex comprising Mtb RNAP, the Mtb ECF σ-factor σL, and promoter DNA (Mtb σL-RPo; PDB 6DVE; ref. 7) and of a posttranslocated-state initial transcribing complex comprising Mtb RNAP, the Mtb ECF σ-factor σL, promoter DNA, and a 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA 5 nt in length (Mtb σL-RPitc5; PDB 6DVB; ref. 7). Here, we determined a higher-resolution crystal structure of a posttranslocated-state initial transcribing complex having a 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNA 5 nt in length (Mtb σL-RPitc5) and crystal structures of posttranslocated-state initial transcribing complexes containing 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNAs 6 and 9 nt in length (Mtb σL-RPitc6 and σL-RPitc9; Fig. 4 B–D and see SI Appendix, Fig. S1D and Table S5). (We also attempted to determine crystal structures of the corresponding complex containing 5′-hydroxyl-containing RNAs 7 and 8 nt in length, but these attempts were unsuccessful, instead yielding structures of pretranslocated-state complexes.) Together with the published structures of Mtb σL-RPo and σL-RPitc5, the structures provide a series of structures in which the position of the RNA 5′-end relative to RNAP varies, and in which the position of RNA 3′-end relative to RNAP remains constant, as in RNA extension in initial transcription (Fig. 4).

In the crystal structures of Mtb σL-RPo and σL-RPitc5, the conformations of the σL finger are identical (Fig. 4 A and B and ref. 7). In the crystal structure of Mtb σL-RPo, template-strand ssDNA was not resolved (Fig. 4A and ref. 7). In the crystal structure of Mtb σL-RPitc5, residue S96 of the σL finger makes H-bonded interaction with the template-strand DNA nucleotide at position −5, preorganizing the template strand to adopt a helical conformation and to engage the RNAP active center (Fig. 4B and ref. 7).

In contrast, in the crystal structures of Mtb σL-RPitc6 and σL-RPitc9, the σL finger adopts different conformations as compared to the structures of Mtb σL-RPo and σL-RPitc5 (Fig. 4 A–D), and the differences in conformation coincide with, and appear to be driven by, the movement of the 5′-end of RNA into the positions previously occupied by the tip of the σ-finger and resulting steric collision between the RNA and the σ-finger (Fig. 4 A–D). In the structure of σL-RPitc6, 2 residues of the σL finger—σL residues 96 and 97—exhibit segmental disorder, indicating that this 2-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 4C). In the structure of σL-RPitc9, 15 residues of the σL finger—σ-residues 86 to 100—exhibit segmental disorder, indicating that this 15-residue segment is flexible and exists as an ensemble of multiple conformations (Fig. 4D). Like the change in conformation of the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor and the σH finger described in the preceding sections, the change in conformation of the σL finger can be understood as the folding of the loop of the σ-finger hairpin back over the strands of the σ-finger hairpin (Fig. 4 B–D). We thus interpret the changes in conformation from σL-RPitc5 to σL-RPitc6 to σL-RPitc9 as successive displacements of the loop of the σ-finger hairpin—involving displacement of first a 2-residue segment and then a 15-residue segment—back over the strands of the σ-finger hairpin, accompanied by increased flexibility of the displaced segments (Fig. 4 B–D).

Taken together, the crystal structures of Mtb σL-RPo, σL-RPitc5, σL-RPitc6, and σL-RPitc9 suggest that nascent RNA with a 5′-hydroxyl end displaces the σ-finger of ECF σ-factor σL in a stepwise fashion, starting upon extension of nascent RNA to a length of 6 nt and continuing upon further extension through a length of at least 9 nt. We conclude that the mechanism of initiation-factor displacement for ECF σ-factor σL is fundamentally similar to the mechanism of initiation-factor displacement for the primary σ-factor, and we suggest that the slight difference in starting points of the process with σL and the primary σ-factor—displacement starting at an RNA length of 6 nt vs. displacement starting at an RNA length of 5 nt—is a consequence of the fact that the σ-finger of σL reaches slightly less deeply—∼5 Å less deeply—into the RNAP active-center cleft than the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Mechanistic Conclusions.

For both the primary σ-factor and the studied ECF σ-factors, the portion of the σ-finger that interacts with template-strand ssDNA in the RNAP-promoter open complex and is displaced in the RNAP-promoter initial transcribing complex is a segment that contains, at its tip, a loop (Figs. 1–4; summary in Fig. 5). For σA, with both 5′-hydroxyl and 5′-triphosphate nascent RNAs, the first step in displacement of the σ-finger is folding of the loop back on itself (Figs. 1 D and E, 2 C and D, and 5 A and B), and successive steps in displacement, which are associated with successive increases in disorder of the loop, are best interpreted as successive steps of folding of the loop further back on itself (Figs. 1 D–G, 2 C–E, and 5 A and B). For ECF σ-factors, the first and successive steps in displacement of the σ-finger entail successive disorder of the loop at the tip of the σ-finger and likewise are best interpreted as successive folding of the loop back on itself (Figs. 3 C–E, 4 B–D, and 5 C and D). We point out that a protein segment that forms a hairpin loop is particularly well suited for stepwise folding back on itself and thus is particularly well suited for stepwise storage of “stress energy” (Fig. 5). We suggest that such a segment may serve as a “protein spring” that is compressed in stepwise fashion during initial transcription, and that this protein spring may contribute—together with a “DNA spring” entailing DNA scrunching (2, 50, 51)—toward stepwise storage of energy required for subsequent breakage of RNAP-promoter and RNAP-σ interactions in promoter escape.

Our results show that the σ-finger plays different roles during different stages of initial transcription (Fig. 5). In early stages of initial transcription, the σ-finger functions as an RNA mimic, preorganizing template-strand ssDNA, first to engage the RNAP active center to enable binding of the initiating and extending NTPs, and then to stabilize the short RNA-DNA hybrids formed by 2- to 4-nt RNA products. In contrast, in later stages of initial transcription, the σ-finger poses a steric and energetic barrier for RNA extension, and collision of the RNA 5′-end with the σ-finger disrupts interactions of the σ-finger with template-strand ssDNA, drives stepwise displacement of the σ-finger, and potentially drives stepwise compression of a σ-finger protein spring, thereby potentially storing energy for use in subsequent breakage of RNAP-promoter and RNAP-σ interactions in promoter escape.

Although we have analyzed only the primary σ-factor and two ECF alternative σ-factors, we note that other alternative σ-factors also have a structural module that enters the active-center cleft and interact with template ssDNA in a manner that blocks the path of nascent RNA (1, 14). Non-ECF alternative σ-factors other than σ54 typically have a σ-finger closely similar in sequence to the σ-finger of the primary σ-factor (1, 14). We predict that non-ECF alternative σ-factors other than σ54 will exhibit the same, or a closely similar, mechanism of stepwise, RNA-driven displacement as for the primary σ-factor, with displacement starting at the same, or a closely similar, RNA length as for the primary σ-factor (i.e., ∼5 nt RNA in posttranslocated state; ∼6 nt RNA in pretranslocated state). σ54 is structurally unrelated to the primary σ-factor and other alternative σ-factors, but, nevertheless, has a structural module, termed RII.3, that contains a loop that makes analogous interactions with template-strand ssDNA (13, 15). We predict that σ54 will exhibit an analogous mechanism of stepwise, RNA-driven displacement, and, based on structural modeling, we predict that displacement will start at the same, or a similar, RNA length as for the primary σ-factor (i.e., ∼5 nt RNA in posttranslocated state; ∼6 nt RNA in pretranslocated state; see SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–C).

Archaeal-RNAP and eukaryotic RNAP-I, RNAP-II, and RNAP-III transcription initiation complexes also contain structural modules—homologous to each other, but not homologous to the relevant structural modules of bacterial σ-factors—that enter the active-center cleft and interact with template ssDNA in a manner that blocks the path of nascent RNA (TFB zinc ribbon and CSB for archaeal RNAP; Rrn7 zinc ribbon and B reader for RNAP-I; TFIIB zinc ribbon and B reader for RNAP-II; and Brf1 zinc ribbon for RNAP-III) (16–18, 21–27, 30). We predict that these structural modules will exhibit an analogous mechanism of stepwise, RNA-driven displacement, and based on structural modeling, we predict that that displacement will start at a similar, RNA length as for the primary σ-factor (i.e., ∼7 nt RNA in posttranslocated state; ∼8 nt RNA in pretranslocated state; see SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A–C).

Methods

Structure Determination.

The assembly and crystallization of the complexes of Figs. 1 and 2 were performed by Y.Z. at Rutgers University, using procedures as in ref. 5. Crystals were obtained using a reservoir solution of 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 10% (m/v) PEG-4000. Structures were determined by the molecular replacement method.

The assembly and crystallization of the complexes of Fig. 3 were performed by L.L. at Shanghai Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, using procedures as in ref. 6. Crystals were obtained using a reservoir solution of 50 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 80 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 15% PEG-400. Structures were determined by the molecular replacement method.

The assembly and crystallization of the complexes of Fig. 4 were performed by V.M. and W.L. at Rutgers University. Crystals were obtained in a reservoir solution of 100 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.6, 200 mM sodium acetate, and 10% (m/v) PEG-4000. Structures were determined by the molecular replacement method.

Detailed methods are provided in SI Appendix.

Data Availability.

Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under ID codes 6LTS, 6KQD, 6KQE, 6KQF, 6KQG, and 6KQH for Tt σA(ρ'513'-'519')-RPo, Tt σA-RPitc3, Tt σA-RPitc4, Tt σA-RPitc5, Tt σA-RPitc6, and Tt σA-RPitc7, respectively; coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6L74, 6KQL, 6KQM, and 6KQN for Tt σA-RPitc2-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc4-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc5-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc6-PPP, respectively; coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6KON, 6KOO, 6KOP, and 6KOQ for Mtb σH-RPitc5, Mtb σH-RPitc7, Mtb σH-RPitc9, and Mtb σH-RPitc10, respectively; and coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6TYE, 6TYF, and 6TYG for Mtb σL-RPitc5, Mtb σL-RPitc6, and Mtb σL-RPitc9, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Strategic Priority Research Program XDB29020000, the National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 31670067 and 31822001 to Y.Z., the CAS Leading Science Key Research Program grant QYZDB-SSW-SMC005 to Y.Z., and NIH grant GM041376 to R.H.E. We thank the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source, the Brookhaven National Synchrotron Light Source II, the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, and the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance during data collection.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under ID codes 6LTS, 6KQD, 6KQE, 6KQF, 6KQG, and 6KQH for Tt σA(△'513'-'519')-RPo, Tt σA-RPitc3, Tt σA-RPitc4, Tt σA-RPitc5, Tt σA-RPitc6, and Tt σA-RPitc7, respectively; coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6L74, 6KQL, 6KQM, and 6KQN for Tt σA-RPitc2-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc4-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc5-PPP, and Tt σA-RPitc6-PPP, respectively; coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6KON, 6KOO, 6KOP, and 6KOQ for Mtb σH-RPitc5, Mtb σH-RPitc7, Mtb σH-RPitc9, and Mtb σH-RPitc10, respectively; and coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6TYE, 6TYF, and 6TYG for Mtb σL-RPitc5, Mtb σL-RPitc6, and Mtb σL-RPitc9, respectively.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1920747117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Feklístov A., Sharon B. D., Darst S. A., Gross C. A., Bacterial sigma factors: A historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 68, 357–376 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkelman J. T., Nickels B., Ebright R. H., “The transition from transcription initiation to transcription elongation: start-site selection, initial transcription, and promoter escape” in In RNA Polymerase as a Molecular Motor, Landick R. W., Strick T., Eds. (RSC Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramm K., Endesfelder U., Grohmann D., A single-molecule view of archaeal transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 4116–4131 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nogales E., Louder R. K., He Y., Structural insights into the eukaryotic transcription initiation machinery. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 59–83 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y., et al. , Structural basis of transcription initiation. Science 338, 1076–1080 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang C., et al. , Structures and mechanism of transcription initiation by bacterial ECF factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 7094–7104 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin W., et al. , Structural basis of ECF-σ-factor-dependent transcription initiation. Nat. Commun. 10, 710 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L., Fang C., Zhuang N., Wang T., Zhang Y., Structural basis for transcription initiation by bacterial ECF σ factors. Nat. Commun. 10, 1153 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami K. S., Masuda S., Darst S. A., Structural basis of transcription initiation: RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 4 A resolution. Science 296, 1280–1284 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vassylyev D. G., et al. , Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 A resolution. Nature 417, 712–719 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basu R. S., et al. , Structural basis of transcription initiation by bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 24549–24559 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuo Y., Steitz T. A., Crystal structures of the E. coli transcription initiation complexes with a complete bubble. Mol. Cell 58, 534–540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y., et al. , TRANSCRIPTION. Structures of the RNA polymerase-σ54 reveal new and conserved regulatory strategies. Science 349, 882–885 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu B., Zuo Y., Steitz T. A., Structures of E. coli σS-transcription initiation complexes provide new insights into polymerase mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 4051–4056 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glyde R., et al. , Structures of RNA polymerase closed and intermediate complexes reveal mechanisms of DNA opening and transcription initiation. Mol. Cell 67, 106–116.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renfrow M. B., et al. , Transcription factor B contacts promoter DNA near the transcription start site of the archaeal transcription initiation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2825–2831 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kostrewa D., et al. , RNA polymerase II-TFIIB structure and mechanism of transcription initiation. Nature 462, 323–330 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X., Bushnell D. A., Wang D., Calero G., Kornberg R. D., Structure of an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB complex and the transcription initiation mechanism. Science 327, 206–209 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sainsbury S., Niesser J., Cramer P., Structure and function of the initially transcribing RNA polymerase II-TFIIB complex. Nature 493, 437–440 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bick M. J., Malik S., Mustaev A., Darst S. A., TFIIB is only ∼9 Å away from the 5′-end of a trimeric RNA primer in a functional RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex. PLoS One 10, e0119007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Y., et al. , Near-atomic resolution visualization of human transcription promoter opening. Nature 533, 359–365 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plaschka C., et al. , Transcription initiation complex structures elucidate DNA opening. Nature 533, 353–358 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel C., et al. , Structural basis of RNA polymerase I transcription initiation. Cell 169, 120–131.e22 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Y., et al. , Structural mechanism of ATP-independent transcription initiation by RNA polymerase I. eLife 6, e27414 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadian Y., et al. , Structural insights into transcription initiation by yeast RNA polymerase I. EMBO J. 36, 2698–2709 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abascal-Palacios G., Ramsay E. P., Beuron F., Morris E., Vannini A., Structural basis of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation. Nature 553, 301–306 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vorländer M. K., Khatter H., Wetzel R., Hagen W. J. H., Müller C. W., Molecular mechanism of promoter opening by RNA polymerase III. Nature 553, 295–300 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulbachinskiy A., Mustaev A., Region 3.2 of the sigma subunit contributes to the binding of the 3′-initiating nucleotide in the RNA polymerase active center and facilitates promoter clearance during initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18273–18276 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pupov D., Kuzin I., Bass I., Kulbachinskiy A., Distinct functions of the RNA polymerase σ subunit region 3.2 in RNA priming and promoter escape. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 4494–4504 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dexl S., et al. , Displacement of the transcription factor B reader domain during transcription initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 10066–10081 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duchi D., et al. , RNA polymerase pausing during initial transcription. Mol. Cell 63, 939–950 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerner E., et al. , Backtracked and paused transcription initiation intermediate of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6562–E6571 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dulin D., et al. , Pausing controls branching between productive and non-productive pathways during initial transcription in bacteria. Nat. Commun. 9, 1478 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami K. S., X-ray crystal structure of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase σ70 holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 9126–9134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernandez V. J., Hsu L. M., Cashel M., Conserved region 3 of Escherichia coli final sigma70 is implicated in the process of abortive transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18775–18779 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cashel M., Hsu L. M., Hernandez V. J., Changes in conserved region 3 of Escherichia coli sigma 70 reduce abortive transcription and enhance promoter escape. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5539–5547 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldman S. R., et al. , NanoRNAs prime transcription initiation in vivo. Mol. Cell 42, 817–825 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vvedenskaya I. O., et al. , Growth phase-dependent control of transcription start site selection and gene expression by nanoRNAs. Genes Dev. 26, 1498–1507 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae B., Feklistov A., Lass-Napiorkowska A., Landick R., Darst S. A., Structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme open promoter complex. eLife 4, e08504 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng Y., Zhang Y., Ebright R. H., Structural basis of transcription activation. Science 352, 1330–1333 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y., et al. , GE23077 binds to the RNA polymerase ‘i’ and ‘i+1’ sites and prevents the binding of initiating nucleotides. eLife 3, e02450 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo X., et al. , Structural basis for NusA stabilized transcriptional pausing. Mol. Cell 69, 816–827.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang J. Y., et al. , RNA polymerase accommodates a pause RNA hairpin by global conformational rearrangements that prolong pausing. Mol. Cell 69, 802–815.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staroń A., et al. , The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: Classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor protein family. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 557–581 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helmann J. D., The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 46, 47–110 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campagne S., Allain F. H., Vorholt J. A., Extra Cytoplasmic Function sigma factors, recent structural insights into promoter recognition and regulation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 30, 71–78 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sineva E., Savkina M., Ades S. E., Themes and variations in gene regulation by extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 36, 128–137 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lane W. J., Darst S. A., The structural basis for promoter -35 element recognition by the group IV sigma factors. PLoS Biol. 4, e269 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campagne S., Marsh M. E., Capitani G., Vorholt J. A., Allain F. H., Structural basis for -10 promoter element melting by environmentally induced sigma factors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 269–276 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapanidis A. N., et al. , Initial transcription by RNA polymerase proceeds through a DNA-scrunching mechanism. Science 314, 1144–1147 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Revyakin A., Liu C., Ebright R. H., Strick T. R., Abortive initiation and productive initiation by RNA polymerase involve DNA scrunching. Science 314, 1139–1143 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under ID codes 6LTS, 6KQD, 6KQE, 6KQF, 6KQG, and 6KQH for Tt σA(ρ'513'-'519')-RPo, Tt σA-RPitc3, Tt σA-RPitc4, Tt σA-RPitc5, Tt σA-RPitc6, and Tt σA-RPitc7, respectively; coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6L74, 6KQL, 6KQM, and 6KQN for Tt σA-RPitc2-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc4-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc5-PPP, Tt σA-RPitc6-PPP, respectively; coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6KON, 6KOO, 6KOP, and 6KOQ for Mtb σH-RPitc5, Mtb σH-RPitc7, Mtb σH-RPitc9, and Mtb σH-RPitc10, respectively; and coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under ID codes 6TYE, 6TYF, and 6TYG for Mtb σL-RPitc5, Mtb σL-RPitc6, and Mtb σL-RPitc9, respectively.