Abstract

Plants are associated with hundreds of thousands of microbes that are present outside on the surfaces or colonizing inside plant organs, such as leaves and roots. Plant-associated microbiota plays a vital role in regulating various biological processes and affects a wide range of traits involved in plant growth and development, as well as plant responses to adverse environmental conditions. An increasing number of studies have illustrated the important role of microbiota in crop plant growth and environmental stress resistance, which overall assists agricultural sustainability. Beneficial bacteria and fungi have been isolated and applied, which show potential applications in the improvement of agricultural technologies, as well as plant growth promotion and stress resistance, which all lead to enhanced crop yields. The symbioses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, rhizobia and Frankia species with their host plants have been intensively studied to provide mechanistic insights into the mutual beneficial relationship of plant–microbe interactions. With the advances in second generation sequencing and omic technologies, a number of important mechanisms underlying plant–microbe interactions have been unraveled. However, the associations of microbes with their host plants are more complicated than expected, and many questions remain without proper answers. These include the influence of microbiota on the allelochemical effect caused by one plant upon another via the production of chemical compounds, or how the monoculture of crops influences their rhizosphere microbial community and diversity, which in turn affects the crop growth and responses to environmental stresses. In this review, first, we systematically illustrate the impacts of beneficial microbiota, particularly beneficial bacteria and fungi on crop plant growth and development and, then, discuss the correlations between the beneficial microbiota and their host plants. Finally, we provide some perspectives for future studies on plant–microbe interactions.

Keywords: endosphere, microbiota, phyllosphere, plant–microbe interaction, rhizosphere

1. Introduction

A microbiota comprises all microbes, including viruses, bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi that are present in a special environment, which is usually investigated together with its host and surrounding environment such as plant, animal gut, and soil, whereas a microbiome includes all the living microorganisms (viruses, bacteria, archaea, and lower and higher eukaryotes), their genomic sequences, and the environmental conditions surrounding the entire habitat [1,2,3]. Microbes are highly diverse and abundantly present in the Earth’s ecosystem, and can survive in extreme environments [1,2]. Microbes are closely associated with their living environment, and environmental changes can alter different microbial species [1,4,5]. Thus, different crop plant species can selectively assemble various microbes in their rhizosphere, phyllosphere, and endosphere [6,7]. Studies have revealed that the microbiota associated with plants is crucial in determining plant performance and health, because certain beneficial microbes improve plant growth and resistance to stresses [8,9,10,11,12].

Crop plants which are cultivated on a large scale in fields for human consumption, livestock feeding, profits, or as raw materials for industrial products are often referred to as agronomic crops [13,14]. With the industrialization and development of human society, improvement of plant productivity and product quality in a natural environment remains a concern. The technologies for crop cultivation have also changed with the use of machines, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides, and thus the composition of microbiota associated with plants has been affected [12,15,16]. Increasing evidence has shown that plant-associated microbiota plays important roles in plant growth and development and is able to provide protection for plants against invading pathogens and various abiotic stresses [17,18]. Moreover, studies have proven that different assemblies of microbiota occur in association with different members of the plant kingdom [19,20,21]. One recent report revealed that the nitrogen (N) absorptions by both the rice (Oryza sativa) indica and japonica species are associated with the NRT1.1B gene, encoding a rice nitrate transporter and sensor, which is responsible for root-associated microbiota composition and N usage in field-grown rice [22]. Community structures of rhizomicrobiomes associated with four traditional Chinese medicinal herbs (Mentha haplocalyx, Perilla frutescens, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, and Astragalus membranaceus) presented significantly different bacterial and fungal communities after culturing in the same soil and air conditions [20].

The advance of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has presented and promoted an effective method for studying the plant–microbe interactions by facilitating the investigations of whole plant-associated microbial communities [23,24,25]. Numerous research groups have focused on studies of microbial communities using the advanced sequencing technologies. For instance, using NGS technologies, Perez-Jaramillo et al. reported a link between the rhizosphere microbiota compositions of domesticated and wild common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) with their genotypic and root phenotypic traits [26], while Shenton et al. performed a study to examine the effects of O. rufipogon (wild rice) and O. sativa (cultivated rice) on the rhizosphere bacterial community compositions [27].

Studies have reported that certain species of bacteria and fungi are closely associated with their host plants [28,29]. Various genera of beneficial microbes associated with crop plants have been studied for their symbiotic formation with the host plants in recent years [30,31]. Previous reports have detailed the importance of microbiota on their host plants; however, only a few reviews have been available on this important topic in a systemic manner [17,18,32]. Thus, in this review, we have made an effort to systemically illustrate the latest research advances of beneficial microbiota associated with crop plants and make suggestions for the research trends on the plant and microbiota relationships.

2. Beneficial Microorganisms for Crop Plants

2.1. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria

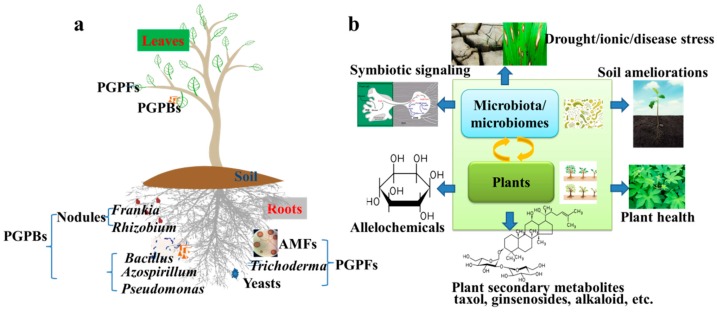

Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPBs) occupy a large proportion of plant microbes and are able to promote plant growth under various environmental conditions in different ways. PGPBs such as beneficial plant-symbiotic bacteria, including rhizobia and Frankia spp., form a symbiotic structure in plant roots [30,31] (Figure 1a). The host plants of rhizobia and Frankia spp. are leguminous and non-leguminous plants (e.g., actinorhizal plants), respectively [30]. The symbiosis of rhizobia with legumes is a host-specific association [33], and the rhizobia from each genus are well known to nodulate a specific host legume to generate nodules that fix atmospheric nitrogen (N2) [33]. Among the rhizobia, the Rhizobium spp. are often associated with chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and common bean, whereas the Bradyrhizobium spp. are largely found to nodulate cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) and soybean (Glycine max) plants [34]. For instance, B. japonicum fixes the N2 to promote plant growth, and thus improves soybean production and reduces the fertilizer requirement in the fields [35]. Rhizobium-legume association is used as a biofertilizer in several countries due to the effective of N2 fixation of rhizobia [36]. It is well known that inoculation of rhizobia also helps to save the N source for cereal production, thus, reducing the application of N fertilizers which in turn conserves the environment [31,37,38,39,40]. Interestingly, Wu et al. indicated that inoculation of rice with one species of rhizobia, Sinorhizobium meliloti, helped rice growth by elevating the expression of genes that function to enhance cell expansion and accelerate cell division [41]. Furthermore, another study revealed that the alliance of arbuscular mycorrhizal (Glomus mosseae) and rhizobial (R. leguminosarum) symbioses alleviated damage to clover (Trifolium repens) by root hemiparasitic Pedicularis species [42].

Figure 1.

(a) Beneficial microbes and microbiota for crop plants. Beneficial microbiota assembles in rhizosphere, phyllosphere, and endosphere. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMFs), Frankia spp. and Rhizobium spp. act as symbionts for plant roots; (b) Future research trends of microbiota and microbiomes associated with crop plants. PGPBs, plant growth-promoting bacteria; PGPFs, plant growth-promoting fungi.

The N2-fixing Frankia, one genus belonging to the actinobacteria group, form the actinorhizal nodules with actinorhizal plants, and promote the growth and abiotic resistance for several woody plants, such as Alnus rubra, Hippophae tibetana, Elaeagnus angustifolia, and Casuarina glauca [30,43,44,45,46]. Root nodule formation in plants by Frankia spp. is a host plant-specific process, and the Frankia spp. can be clustered into three clusters that include some identified species, namely (1) Frankia alni, F. casuarinae, and F. torreyi; (2) F. coriariae and F. datiscae; and (3) F. elaeagni and F. irregularis, which represent the associated Alnus, Dryas and Elaeagnus hosts, respectively [47,48,49]. Ngom et al. determined that the Frankia spp. in Cluster 1 can also promote the growth of Casuarina glauca through symbiosis [50]. Several reports revealed that Alnus, Hippophae, and Elaeagnus plants can resist drought and salt stress with the help of specific Frankia strains [51,52]. On the basis of the results of genome analyses, Frankia strains possess some shared or specific genes for promoting plant growth, as well as genes related to N2 fixation [49]. Further studies are required to understand the underlying mechanisms, as well as the clustering of the Frankia species based on their specific symbiotic relationship with the host plants [52,53,54].

Other types of PGPBs, either residing in the rhizosphere or phyllosphere or endosphere, can also promote plant growth and stress resistance [5]. These PGPBs have some beneficial traits, such as the ability to produce indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase and siderophores, as well as to solubilize phosphate [55,56,57]. Furthermore, some PGPBs also compete with certain pathogenic bacteria or fungi for nutrients or niches, and thus inhibit the spread of pathogens and reduce damage to plants [58]. Some PGPB species of Bacillus and Pseudomonas genera have been studied for their potential applications in sustainable agriculture development [59,60,61]. For instance, PGPBs belonging to Bacillus and Pseudomonas, as well as Azospirillum and Azotobacter genera were shown to improve alkaloid contents in the medicinal plant Withania somnifera in a two-consecutive-year experiment [62], while P. putida and P. fluorescens were proven to improve tropane alkaloid production in Hyoscyamus niger plants under water scarcity [63]. In this context, Maggini et al. proposed Echinacea purpurea as a new model plant to study crosstalk between medicinal plants and bacterial endophytes, with the aim to discover bioactive compounds [64]. Their suggestion was made based on the finding that the secondary metabolite levels in non-infected and infected plants were different, indicating that the bacterial infection modulated the biosyntheses of several secondary metabolites [64]. Additionally, the transcript levels of a gene involved in the alkamide metabolic pathway were higher in the roots of infected E. purpurea than in that of the non-infected control [64]. Several secondary metabolites produced by PGPBs can also be used to control pathogens and salinity [60,65]. Several studies have also reported that PGPBs lead to induced systemic resistance (ISR) in plants, which helps the plants to resist the pathogens [66,67,68] (Figure 1b).

2.2. Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi

Plant growth-promoting fungi (PGPFs) have gained immense attention as biofertilizers due to their role in maintaining plant quality and quantity and their environment-friendly relationship [69] (Figure 1a). Advancements in the development of PGPFs for crop cultivation have been achieved in Salvia miltiorrhiza, grapevine (Vitis vinifera), and lettuce (Lactuca sativa) [69,70,71,72]. For instance, Trichoderma spp., Ganoderma spp., and yeasts (Saccharomyces spp.) have been used as PGPFs in several studies under both normal growth and environmental stress conditions [70,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. For example, Jaroszuk-Scisel et al. reported that a Trichoderma strain, isolated from a healthy rye (Secale cereale) rhizosphere with the ability to produce auxin, gibberellins, and ACC deaminase in vitro, and to inhibit the growth of Fusarium spp., could colonize the roots of wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings and enhance stem growth [73]. Another study revealed that T. asperellum could induce peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase, as well as the cell wall degrading enzymes chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase in lettuce plants to defend the infected plants against the leaf spot disease [70]. Several isolated killer yeast S. cerevisiae strains were shown to serve as PGPFs for controlling Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in grape planting [80]. Cell wall isolated from yeast (Rhodosporidium paludigenum) could induce disease resistance against Penicillium expansum in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) fruits by inducing the activities of defense-associated enzymes such as β-1,3-glucanase and chitinase, and by upregulating expression of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes in plants [75].

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMFs), equal to the term ”Glomeromycota” at the fungal phylum level, can benefit plants as PGPFs during nutrient absorption and stress resistance by acting as symbionts to their hosts [81,82] (Figure 1a). Being one group of obligate endomycorrhizas that has occurred for nearly 400 million years, AMFs also play a key role in liverworts (Marchantiophyta), hornworts (Ceratophyllum demersum) and lycophytes by helping them adapt to the land during the early years [83]. Spagnoletti et al. reported that AMFs promote soybean production by helping soybean plants resist arsenic (As) contaminated soils [82], while Cely et al. indicated that inoculation of Rhizophagus clarus increased the soybean production under field conditions [84]. Moreover, AMFs improved rice production by reducing the total content of As, and improving the nitrogen/carbon (N:C) ratio in rice grains [85,86]. Furthermore, one study reported that selenium (Se) × AMF interactions promoted both soybean and forage grass (Urochloa decumbens) for Se absorption, which improved the quality of the two plants used as animal feed [87]. Rhizoglomus intraradices, one model species of AMFs, help rice, soybean, ginseng (Panax ginseng), and other crops resist drought and cold stresses and promote nutrient absorption [10,88,89]. R. intraradices also promoted rice plants to resist blast disease (caused by Magnaporthe oryzae spores), and the transcriptome data revealed that R. intraradices-inoculated rice plants exhibited significantly higher expression levels of genes related to the auxin and salicylic acid signaling pathways than the noninoculated rice plants in response to M. oryzae [11].

2.3. Biocontrol Agents

The biocontrol agents (BCAs), including various beneficial AMFs, PGPBs, and PGPFs have been investigated by several scientists in the last 30 years [11,90,91,92,93]. For example, various species of Pseudomonas, Saccharomyces, Streptomyces, and Trichoderma genera are the most effective BCAs that help plants acquire nutrients and control the plant pathogens [71,91,94]. These species possess a number of antagonistic mechanisms, including competition for nutrients and space with pathogenic fungi or bacteria, producing antifungal and bacterial compounds for resisting pathogenic fungi and bacteria, and direct parasitism [71,91,94]. In addition, these microbes can trigger plant resistance by strengthening the cell wall and enhancing the physiological and biochemical responses of plants to stresses [95].

3. Why Plants Need Beneficial Microbiota

As discussed above, a myriad of microbes populated on plant surfaces or inside the plants can considerably affect plant growth, nutrient uptake, and resistance to environmental stresses [11,90,91,92,93]. Therefore, gaining deep insights into the mechanisms underlying the evolution, compositions, and functions of plant microbiomes would open new avenues to enhance crop health and yield, ensuring global food security [96]. Wei et al. proposed a framework for plant breeding, which would enable plants to obtain economically novel phenotypes by altering plants’ genomic information along with plant-associated microbiota [97]. In the breeding strategy of plants, microbes are considered to be one of the direct targets subjected to selection for achieving a desirable plant phenotype [97].

Bai et al. reported different bacterial communities in the rhizophere and phyllosphere [98]. Roots secrete some organic C and N sources into the rhizosphere, which help in enrichment and assembly of the soil microbes in the rhizosphere [99,100,101]. A number of studies have revealed that the correlation between microbiota and related metabolic pathways in plants mutually affects the growth and responses of plants to environmental stresses [21,102,103]. Considering various compounds secreted by different plants, a different rhizosphere microbiota is associated with a different plant species to support their performance and stress resistance [20,104,105]. The beneficial microbiota, containing AMFs, PGPBs, and PGPFs, also affects the metabolism of various substances in plants [10,106,107]. This mutual relationship between microbiota and plants effectively supports plant performance and resistance to adverse environmental conditions [8,9,10,11] (Figure 1b).

Soil represents an extremely rich microbial reservoir on the Earth [108]. Soil is the origin of the rhizosphere microbiota, and a driver of microbial community formation [109,110]. The diversity and abundance of a microbiota in soil are about (1~10) × 109 CFU bacteria/g soil and (1~10) × 105 colony-forming unit (CFU) fungi/g soil in normal soils [111,112]. Rhizosphere is the soil surrounding the plant roots within 2 to 5 mm, in which numerous microbes assemble [25,113,114]. The rhizosphere of the crop plants acts as the major ecological environment for establishment of plant–microbe interactions. The mutual interactions involve colonization of numerous microbes growing in the inner parts or on the surface of roots, and the microbiota result in associative, symbiotic, and even parasitic collaborations among the plants and the associated microflora [115,116]. Soil, as the natural medium for bacteria and fungi, provides C and N sources needed by these microbes [117,118]; however, these C and N sources are normally provided by plants, further illustrating the mutual relationship between plants and microbes. Furthermore, the soil characteristics differ due to the flora grown on it, the microbes in the soil, and soil management by humans [19,20,119].

Whereas the use of chemicals, such as insecticides, herbicides and pesticides, hampers the quality of plant products, and thus adversely affects human health [120,121], extracts and metabolites of PGPBs and PGPFs effectively protect plants from various biotic and abiotic adversities [60,77,122]. Thus, if the microbiota containing PGPBs and PGPFs is effectively used, the problems regarding crop production could be solved in an efficient and environment-friendly manner. Endophytic microbiota residing inside the roots, stems, and leaves of plants help to maintain plant health and help plants resist adverse conditions [123]. It has been reported that plants selectively construct the community of their endophytic microbiota, which helps in upregulating expression levels of stress resistance-related genes in plants [123].

In addition, plants need soil microbiota for degrading their residues [124]. Plant residues are abundantly found in the soil [124,125]. Although chemical or physical methods can help degrade the residues, the natural degradation is carried out by soil microbes [125]. The microbiota assembles and is enriched in the plant residues and further degrades them into macro- or micromolecules, which can serve as soil organic matter [125]. For instance, the utilization of plant residues and enrichment of soil microbiota could improve the organic matter content and composition of the soils in northeast China [126,127]. Improved soil organic matter properties protect the soil from destruction and maintain its nutrient content, which would make the soil more suitable for crop production [128,129]. In addition, when plants are grown under biotic or abiotic stress conditions, such as in pathogenic fungi-contaminated, heavy metal-contaminated, or alkaline soils, the plant-associated microbiota helps them resist stresses by mediating plant abscisic acid (ABA) levels, plant jasmonic acid (JA) levels, or Bradford reactive soil protein protection [11,130,131].

4. Influences of the Community Compositions of Rhizosphere, Phyllosphere, and Endosphere Microbiota on Growth and Performance of Crop Plants

A few advances have been made to illustrate the diversity and community structure of the microbes associated with crop plants, and their relationship with the changes in plant metabolites and gene expression [21,102,132]. Community compositions of the rhizosphere, phyllosphere, or endosphere microbiota associated with plants indicate the health or nutrient conditions of the plants [21,115,116,133,134]. On the one hand, the highly enriched pathogenic fungi in the rhizosphere indicate stress conditions that can adversely affect the growth of crop plants [10,135]. On the other hand, the beneficial rhizospheric microbes improve plant growth, nutrient absorption, and development based on the mechanisms, such as organic matter mineralization, disease containment against soil-borne pathogens, N2 fixation, potassium (K) and phosphate solubilization, and IAA and ACC deaminase production [115,116]. Thus, the soil/plant/microbial relationship must be appropriately maintained for sustainable agricultural practices [115,116]. Phyllospheric microbes, consisting of mostly bacteria and fungi, can act as (i) beneficial mutualists that improve plant growth and resistance to environmental stresses; (ii) commensals that use the leaf habitat for their own growth, development, and reproduction; or (iii) antagonistic pathogens [136,137,138] (Figure 1a). A study of 14 phylogenetically diverse plant species grown under controlled greenhouse conditions showed high presentation of Bacillus and Stenotrophomonas genera in their phyllosphere microbial communities, which showed antagonistic potential toward Botrytis cinerea [134], a foliar pathogen that causes gray mold disease in more than 200 dicot crop plants [139].

Endophytic bacteria and fungi, inhabiting within the plant tissues, play crucial roles in plant growth, fitness, development and protection without causing any evident damage to the host plants [140,141]. These endophytic bacteria and fungi reside on intercellular spaces in the plants for a certain period of their life cycle, and obtain carbohydrates, amino acids, and inorganic nutrients from their hosts [142]. Some endophytic bacteria or fungi also produce IAA, soluble phosphate, and siderophores, which can promote the host plant growth [143]. For instance, Borah et al. studied the endophytic microbes of cultivated rice (O. sativa) and wild rice (O. rufipogon) plants and reported their diversity in terms of their functional characteristics related to multiple traits associated with promotion of plant growth and development [144]. Murphy et al. screened fungal endophytes from wild barley (Hordeum murinum) for testing the beneficial and promoting traits in cultivated barley (H. vulgare) and found that some fungi could promote the growth of cultivated barley [145].

Furthermore, a few studies have reported that both artificial management of plant growth environment and conditions, and plant domestication affect the community structure of rhizosphere and endosphere microbiomes [27,119,146,147]. Wild plant species preserve more diversity in associated microbiota for their survival against stress resistance than the domesticated crops. A recent study reported that common wild rice (O. rufipogon) grown in wildland of lower soil nutrients showed higher rhizobacterial diversity than the cultivated rice grown under cultivated field conditions with higher soil nutrient [28]. Martín-Robles et al. discussed the impacts of domestication on the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses of 14 crop species under different available phosphorus conditions, and reported that in response to increased available phosphorus, domestication decreased the AMF colonization in domesticated plants as compared with their wild progenitors [148]. Thus, more studies revealing the influence of plant domestication on the compositions of microbiomes are warranted, and the rhizosphere microbiota in wild and cultivated species grown in the field conditions are essentially required to study the correlation of microbiota and host plants.

A plant can release various chemical compounds into the environment that impose either direct or indirect allelochemical effect on another plant [149] (Figure 1b). In addition, studies have revealed that the production of allelochemicals by plants significantly alters the structure of associated microbiomes [150,151,152]. However, the influence of microbiota on the allelochemical production in plants remains unclear. Moreover, the relationships of specific allelochemicals with a particular microbiota remain unillustrated. A recent study by Li et al. concluded that replantation of Sanqi ginseng (P. notoginseng) is not recommended mainly due to the accumulation of soil-borne pathogens and allelochemicals (e.g., ginsenosides) [153]. Li et al. also demonstrated that reductive soil disinfestation approach could effectively alleviate the replantation failure of Sanqi ginseng with allelochemical degradation and pathogen suppression [153] (Table 1). However, the reason behind the continuous cropping obstacle on the community compositions of microbiomes remains the task of future research.

Table 1.

Several representative applications of microbes in crop plants. ACC, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid; AMFs, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; JA, jasmonic acid; ABA, abscisic acid; PGPBs, plant growth-promoting bacteria; PGPFs, plant growth-promoting fungi.

| Research Aspects | Microbes/ Microbiomes |

Beneficial Traits | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizobia/ Frankia in colonization with host plants | Rhizobia/ Frankia spp. |

Rhizobium spp. promoted the growth of rice seedlings and solubilized silicate; | [160] |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum helped soybean in resisting arsenic contamination in soil | [161] | ||

| Frankia casuarinae CcI3 formed nodules and promoted the growth of Casuarina equisetifolia | [163] | ||

| Positive effects of mutualistic symbioses with fungi on stress resistance | AMFs | Rhizoglomus intraradices reduced the relative abundance of pathogenic fungi in plant soil | [10] |

| AMFs promote rice and wheat in resisting drought | [158,159] | ||

| PGPB/PGPF applications in improving plant growth, productivity, and resistance | PGPBs | Productions of IAA, ACC deaminases, JA and ABA | [55,56,57] |

| PGPFs | Trichoderma spp. and yeasts help plant in resisting diseases | [70,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] | |

| Allelochemical effects/soil ameliorations | Microbiomes in soil | Reductive soil disinfestation can reduce the allelochemical effect in soil. | [153] |

| Soil amendments associated with changes in the compositions of soil microbiomes | [19,119] | ||

| Effects of microbiota on the production of secondary metabolites in plants | PGPBs/AMFs/Paraconiothyr-ium | AMFs improve the content of gesenosides in P. ginseng planting | [10] |

| Endophytic fungi Paraconiothyrium spp. in Taxus chinensis can produce taxol | [171,172,173] | ||

| Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Pseudomonas and Bacillus improved the alkaloid content in Withania somnifera | [62] | ||

| P. putida and P. fluorescens were proved to improve tropane alkaloid production of Hyoscyamus niger under water deficit stress | [63] |

5. Applications of Individual Microbes for Improvement of Crop Performance and Soil Ameliorations

Various beneficial microorganisms have been commercialized [154]; however, their efficacy has not always been consistent in terms of benefiting crop plants in fields. Nevertheless, combining beneficial microbes for application to crop plants has been shown to be more effective in improving plant performance. The PGPBs and PGPFs have been applied in agricultural practices for 30 years. For instance, applications of the AMFs have been known to improve the yield of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and soybean, as well as soybean resistance to the Macrophomina phaseolina pathogen and stress associated with As [82,84]. AMFs also promote N transfer from soil to plants as indicated by a study of Tian et al., in carrot (Daucus carota) [155]. The authors also reported that R. intraradices-mediated N transfer successively induced the expression of N metabolism-related genes in the intraradical and extraradical mycelia, as well as in the host plants [155]. The interactive effects of the AMF R. irregularis and the PGPB P. putida synergistically improved the growth and defence of the wheat host plants against pathogens [156]. With the global warming, drought has been one of the major limiting conditions for crop production [157]. Studies have shown that AMFs enhanced rice and wheat in resisting drought by improving the plant physiological index [158,159]. Application of PGPBs such as Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Pseudomonas, and Bacillus species improved the alkaloid contents in two medicinal plants W. somnifera and H. niger under limited water conditions [62,63]. With regards to the endosymbiotic PGPBs, Chandrakala et al. screened and isolated one Rhizobium species from rice rhizosphere, which could solubilize silicate and promote plant growth potential of the rice plants [160]. B. japonicum has been shown to help soybean to resist a high content of As in the soil [161], whereas S. fredii could effectively nodulate numerous different legumes, thereby promoting growth of the host plants [162]. Vemulapally et al. screened and isolated Frankia spp. from the nodules of Casuarina spp., one of which (F. casuarinae CcI3 strain) could form nodules in roots of C. equisetifolia seedlings after its inoculation to the plants and promote plant growth [163]. Forchetti et al. demonstrated that certain bacterial species can produce JA and ABA [4]. However, whether the contents of these hormones in plants can be influenced directly by the associated microbes remains unclear. Nevertheless, hormone-producing bacteria or fungi are not always beneficial; for example, Gibberella fujikuroi can produce gibberellin and cause rice bakanae disease [164] (Table 1). Thus, studies on the mutual effects of microbes and host plants on hormone metabolism in both plants and microbes in the context of plant and microbiota relationships have been novel and interesting, and thus this topic would deserve more attention from the research community.

Microbe-mediated remediation of environmental contaminants requires more research for heavy metal-polluted soils and saline-sodic soils (Figure 1b). With the industrialization, environmental contaminants, such as heavy metal, household garbage, and excessive N and phosphate in the soil or water, have seriously affected the quality of humans’ and plants’ life. Mitigation of heavy metal contamination in soil by fungal bioremediation has proceeded for several years [165,166], and studies for exploring heavy metal-polluted soils for agriculture by cultivating stress-tolerant plants with the help of microbes are also in process [167]. Cornejo et al. revealed that AMFs assisted Oenothera picensis in resisting copper stress and helped the bioremediation of copper-polluted soil [130]. Saline-sodic soils have been studied for several years to improve their soil characteristics for crop cultivation with higher productivity [19,119]. Chemical and biological ameliorations of saline-sodic soils are the most effective ways; however, both methods affect the compositions of soil microbiomes. For example, Luo et al. revealed that ameliorations of saline-sodic soils by using chemicals or plant planting affected the soil microbiota [19,168], while Shi et al. found various responses of microbial communities and enzyme activities to various chemical and biological amendments in the saline-alkaline soils [119] (Table 1). Research on plant-associated microbiota to improve the soil characteristics is further warranted to facilitate microbiota applications in different aspects of agriculture and life, and more studies considering microbiota applications along with plant cultivation for soil ameliorations are required.

As discussed earlier, beneficial microbes can also improve the useful secondary metabolites in medicinal plants, demonstrating the wide application potential of microbes and microbiota to various types of crops. Application of a microbial consortium of various PBGBs, including Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Pseudomonas, and Bacillus spp., improved the levels of alkaloids, which have pharmacological properties [62,63], in W. somnifera and H. niger [62,63]. Furthermore, Huang et al. advocated S. miltiorrhiza, which is a herb widely used in traditional Chinese medicine, as a model species for investigating how different microbes can interact with medicinal plants to alter the production of phytochemical compounds [169]. Additionally, it is well known that Taxus chinensis can produce taxol, an anticancer metabolite [170], and its endophytic fungi Paraconiothyrium spp. can also produce the same anticancer metabolite [171,172,173]. However, it is not clear whether the content of taxol in T. chinensis could be improved by its endophytic fungi, as well as the relationship of T. chinensis and associated microbiota in terms of metabolite production has also not yet been determined. Thus, the effect of microbiota on the metabolic pathways of their host plant deserves more studies in future (Figure 1b).

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Microbiota plays important roles in plant growth, development, productivity, and resistance to environmental stresses. An increasing body of research has been focusing on the associations and relationships between microbiota and host plants. Although some progresses have been made in recent years, applications of microbes and microbiota to improve crop productivity still require more research. Both theoretical research and applied research of microbes and microbiota in connection with plants remain a major task for the scientific community. In the future, AMFs, PGPBs, and PGPF should be applied and utilized more effectively in agriculture. The signaling pathways of AMFs, and rhizobia and Frankia spp. with their host plants have been studied for a long time but are still under debate in plant science. Various genes in microbes related to hormones such as strigolactones and nutrient uptake similar to nitrogen uptake should be studied to uncover the mutual connection with the host plants.

In the future, microbiota research using both basic and applied research approaches in connection with crop plants should be focused on the following: (1) Mutualistic symbioses of the fungal and bacterial microbes with the host plants; (2) plant diseases caused by the environmental microbiota; (3) mechanistic studies and explorations of PGPBs and PGPFs for the improvement of plant growth, productivity and resistance, and yield quality; (4) allelochemical effects between plants and microbiota; and (5) mechanisms underlying the degradation of plant residues by the microbiota for acceleration of practical use in this field. Future research on plant and microbiota associations and relationships could play an essential role in ensuring food security in response to global climate change.

Acknowledgments

Thanks Dr. Eiko E Kuramae and Pr. Johannes A. van Veen (Netherlands Institute of Ecology NIOO-KNAW, Department of Microbial Ecology) for their constructive suggestions to improve our article.

Abbreviations

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| AMFs | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| BCAs | biocontrol agents |

| PGPBs | plant growth-promoting bacteria |

| PGPFs | Plant growth-promoting fungi |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| IAA | indole-3-acetic acid |

Author Contributions

All authors are involved in the writing of this review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financially supported by the Special Foundation for Basic Research Program in Wild China of CAS (XDA23070500), the Special Foundation for State Major Basic Research Program of China (2016YFC0501202), the Special Foundation for Basic Research Program in Soil of CAS (XDB15030103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41571255, 41701332, 41920104008), the Key Research Program of CAS (KFZD-SW-112), Cooperative Project between CAS and Jilin Province of China (2019SYHZ0039), the Science and Technology Development Project of Changchun City of China (18DY019), and the Science and Technology Development Project of Jilin Province of China (20180519002JH, 20190303070SF).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gibbons S.M., Gilbert J.A. Microbial diversity—Exploration of natural ecosystems and microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015;35:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedrós-Alió C., Manrubia S. The vast unknown microbial biosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:6585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606105113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesi J.R., Ravel J. The vocabulary of microbiome research: A proposal. Microbiome. 2015;3:31. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forchetti G., Masciarelli O., Alemano S., Alvarez D., Abdala G. Endophytic bacteria in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.): isolation, characterization, and production of jasmonates and abscisic acid in culture medium. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2007;76:1145–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orozco-Mosqueda M.d.C., Rocha-Granados M.d.C., Glick B.R., Santoyo G. Microbiome engineering to improve biocontrol and plant growth-promoting mechanisms. Microbiol. Res. 2018;208:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick C.R., Copeland J., Wang P.W., Guttman D.S., Kotanen P.M., Johnson M.T.J. Assembly and ecological function of the root microbiome across angiosperm plant species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:1157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717617115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zgadzaj R., Garrido-Oter R., Jensen D.B., Koprivova A., Schulze-Lefert P., Radutoiu S. Root nodule symbiosis in Lotus japonicus drives the establishment of distinctive rhizosphere, root, and nodule bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:7996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616564113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferentinos K.P. Deep learning models for plant disease detection and diagnosis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018;145:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2018.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nejat N., Rookes J., Mantri N.L., Cahill D.M. Plant-pathogen interactions: Toward development of next-generation disease-resistant plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017;37:229–237. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2015.1134437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian L., Shi S., Ma L., Zhou X., Luo S., Zhang J., Lu B., Tian C. The effect of Glomus intraradices on the physiological properties of Panax ginseng and on rhizospheric microbial diversity. J. Ginseng Res. 2019;43:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian L., Chang C., Ma L., Nasir F., Zhang J., Li W., Tran L.S.P., Tian C. Comparative study of the mycorrhizal root transcriptomes of wild and cultivated rice in response to the pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae. Rice. 2019;12:35. doi: 10.1186/s12284-019-0287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaparro J.M., Sheflin A.M., Manter D.K., Vivanco J.M. Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2012;48:489–499. doi: 10.1007/s00374-012-0691-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fageria N.K. In: The Use of Nutrients in Crop Plants. Fageria N.K., editor. CRC Press; New York, NY, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrt C.S., Munns R., Burton R.A., Gilliham M., Wege S. Root cell wall solutions for crop plants in saline soils. Plant Sci. 2018;269:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt P., Nailwal T.K. Chapter 11—Crop Improvement through Microbial Technology: A Step toward Sustainable Agriculture. In: Prasad R., Gill S.S., Tuteja N., editors. Crop Improvement through Microbial Biotechnology. Elsevier; New Delhi, India: 2018. pp. 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altieri M.A., Nicholls C.I., Montalba R. Technological approaches to sustainable agriculture at a crossroads: an agroecological perspective. Sustainability. 2017;9:349. doi: 10.3390/su9030349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller D.B., Vogel C., Bai Y., Vorholt J.A. The plant microbiota: systems-level insights and perspectives. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016;50:211–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-034952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain S.S., Mehnaz S., Siddique K.H.M. Harnessing the Plant Microbiome for Improved Abiotic Stress Tolerance. In: Egamberdieva D., Ahmad P., editors. Plant Microbiome: Stress Response. Springer; Singapore: 2018. pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo S., Tian L., Chang C., Wang S., Zhang J., Zhou X., Li X., Tran L.S.P., Tian C. Grass and maize vegetation systems restore saline-sodic soils in the Songnen Plain of northeast China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018;29:1107–1119. doi: 10.1002/ldr.2895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi S., Tian L., Ma L., Tian C. Community structure of rhizomicrobiomes in four medicinal herbs and its implication on growth management. Microbiology. 2018;87:425–436. doi: 10.1134/S0026261718030098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi S., Tian L., Nasir F., Li X., Li W., Tran L.S.P., Tian C. Impact of domestication on the evolution of rhizomicrobiome of rice in response to the presence of Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;132:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J., Liu Y.X., Zhang N., Hu B., Jin T., Xu H., Qin Y., Yan P., Zhang X., Guo X., et al. NRT1.1B is associated with root microbiota composition and nitrogen use in field-grown rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:676–684. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlaeppi K., Bulgarelli D. The plant microbiome at work. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014;28:212–217. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-14-0334-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasir F., Tian L., Shi S., Chang C., Ma L., Gao Y., Tian C. Strigolactones positively regulate defense against Magnaporthe oryzae in rice (Oryza sativa) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019;142:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian L., Shi S., Ma L., Tran L.S.P., Tian C. Community structures of the rhizomicrobiomes of cultivated and wild soybeans in their continuous cropping. Microbiol. Res. 2020;232:126390. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2019.126390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Jaramillo J.E., Carrion V.J., Bosse M., Ferrao L.F.V., de Hollander M., Garcia A.A.F., Ramirez C.A., Mendes R., Raaijmakers J.M. Linking rhizosphere microbiome composition of wild and domesticated Phaseolus vulgaris to genotypic and root phenotypic traits. ISME J. 2017;11:2244–2257. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shenton M., Iwamoto C., Kurata N., Ikeo K. Effect of wild and cultivated rice genotypes on rhizosphere bacterial community composition. Rice. 2016;9:42–53. doi: 10.1186/s12284-016-0111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian L., Zhou X., Ma L., Xu S., Nasir F., Tian C. Root-associated bacterial diversities of Oryza rufipogon and Oryza sativa and their influencing environmental factors. Arch. Microbiol. 2017;199:563–571. doi: 10.1007/s00203-016-1325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeoh Y.K., Dennis P.G., Paungfoo-Lonhienne C., Weber L., Brackin R., Ragan M.A., Schmidt S., Hugenholtz P. Evolutionary conservation of a core root microbiome across plant phyla along a tropical soil chronosequence. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:215. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cissoko M., Hocher V., Gherbi H., Gully D., Carré-Mlouka A., Sane S., Pignoly S., Champion A., Ngom M., Pujic P., et al. Actinorhizal signaling molecules: Frankia root hair deforming factor shares properties with NIN inducing factor. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1494. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole P., Ramachandran V., Terpolilli J. Rhizobia: from saprophytes to endosymbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:291–303. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Escudero-Martinez C., Bulgarelli D. Tracing the evolutionary routes of plant–microbiota interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019;49:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batista L., Irisarri P., Rebuffo M., Cuitiño M.J., Sanjuán J., Monza J. Nodulation competitiveness as a requisite for improved rhizobial inoculants of Trifolium pratense. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2015;51:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00374-014-0946-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koskey G., Mburu S.W., Kimiti J.M., Ombori O., Maingi J.M., Njeru E.M. Genetic characterization and diversity of Rhizobium isolated from root nodules of mid-altitude climbing bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:968. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronner E., Franke A.C., Vanlauwe B., Dianda M., Edeh E., Ukem B., Bala A., van Heerwaarden J., Giller K.E. Understanding variability in soybean yield and response to P-fertilizer and rhizobium inoculants on farmers’ fields in northern Nigeria. Field Crop Res. 2016;186:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mia M.B., Shamsuddin Z. Rhizobium as a crop enhancer and biofertilizer for increased cereal production. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:6001–6009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crespo-Rivas J.C., Navarro-Gomez P., Alias-Villegas C., Shi J., Zhen T., Niu Y., Cuellar V., Moreno J., Cubo T., Vinardell J.M., et al. Sinorhizobium fredii HH103 RirA is required for oxidative stress resistance and efficient symbiosis with soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:787. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao J., Zhang N., Liu H., Wang H., Zhong Z., Zhu J. Soil commensal rhizobia promote Rhizobium etli nodulation efficiency through CinR-mediated quorum sensing. Arch. Microbiol. 2018;200:685–694. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siczek A., Lipiec J. Impact of faba bean-seed rhizobial inoculation on microbial activity in the rhizosphere soil during growing season. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:784. doi: 10.3390/ijms17050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozturk A., Caglar O., Sahin F. Yield response of wheat and barley to inoculation of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria at various levels of nitrogen fertilization. J. Plant Nut. Soil Sci. 2003;166:262–266. doi: 10.1002/jpln.200390038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Q., Peng X., Yang M., Zhang W., Dazzo F.B., Uphoff N., Jing Y., Shen S. Rhizobia promote the growth of rice shoots by targeting cell signaling, division and expansion. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018;97:507–523. doi: 10.1007/s11103-018-0756-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sui X.L., Zhang T., Tian Y.Q., Xue R.J., Li A.R. A neglected alliance in battles against parasitic plants: arbuscular mycorrhizal and rhizobial symbioses alleviate damage to a legume host by root hemiparasitic Pedicularis species. New Phytol. 2019;221:470–481. doi: 10.1111/nph.15379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Nguyen T., Pawlowski K. Frankia and Actinorhizal Plants: Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. In: Mehnaz S., editor. Rhizotrophs: Plant Growth Promotion to Bioremediation. Springer; Singapore: 2017. pp. 237–261. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berry A.M., McIntyre L., McCully M.E. Fine structure of root hair infection leading to nodulation in the Frankia–Alnus symbiosis. Can. J. Bot. 1986;64:292–305. doi: 10.1139/b86-043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian C., He X., Zhong Y., Chen J. Effects of VA mycorrhizae and Frankia dual inoculation on growth and nitrogen fixation of Hippophae tibetana. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002;170:307–312. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00781-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gtari M., Brusetti L., Skander G., Mora D., Boudabous A., Daffonchio D. Isolation of Elaeagnus-compatible Frankia from soils collected in Tunisia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006;234:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samant S., Dawson J.O., Hahn D. Growth responses of introduced Frankia strains to edaphic factors. Plant Soil. 2016;400:123–132. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2720-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolters D.J., Van Dijk C., Zoetendal E.G., Akkermans A.D.L. Phylogenetic characterization of ineffective Frankia in Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. nodules from wetland soil inoculants. Mol. Ecol. 1997;6:971–981. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nouioui I., Cortés-albayay C., Carro L., Castro J.F., Gtari M., Ghodhbane-Gtari F., Klenk H.P., Tisa L.S., Sangal V., Goodfellow M. Genomic insights into plant-growth-promoting potentialities of the genus Frankia. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ngom M., Diagne N., Laplaze L., Champion A., Sy M.O. Symbiotic ability of diverse Frankia strains on Casuarina glauca plants in hydroponic conditions. Symbiosis. 2016;70:79–86. doi: 10.1007/s13199-015-0366-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J.T., Tsai S.M. The nitrogen-fixing Frankia significantly increases growth, uprooting resistance and root tensile strength of Alnus formosana. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2018;17:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ngom M., Oshone R., Diagne N., Cissoko M., Svistoonoff S., Tisa L.S., Laplaze L., Sy M.O., Champion A. Tolerance to environmental stress by the nitrogen-fixing actinobacterium Frankia and its role in actinorhizal plants adaptation. Symbiosis. 2016;70:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s13199-016-0396-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rey T., Dumas B. Plenty is no plague: Streptomyces symbiosis with crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Numan M., Bashir S., Khan Y., Mumtaz R., Shinwari Z.K., Khan A.L., Khan A., Al-Harrasi A. Plant growth promoting bacteria as an alternative strategy for salt tolerance in plants: A review. Microbiol. Res. 2018;209:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Misra S., Dixit V.K., Khan M.H., Kumar Mishra S., Dviwedi G., Yadav S., Lehri A., Singh Chauhan P. Exploitation of agro-climatic environment for selection of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase producing salt tolerant indigenous plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiol. Res. 2017;205:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patil N., Inchanalkar M., Desai D., Landge V., Bhole B.D. Screening of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase producing multifunctional plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from onion (Allium cepa) rhizosphere. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2016;5:118–127. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2016.510.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jogaiah S., Kurjogi M., Govind S.R., Huntrike S.S., Basappa V.A., Tran L.S.P. Isolation and evaluation of proteolytic actinomycete isolates as novel inducers of pearl millet downy mildew disease protection. Sci. Rep. UK. 2016;6:30789. doi: 10.1038/srep30789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hassan M.K., McInroy J.A., Kloepper J.W. The interactions of rhizodeposits with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in the rhizosphere: A review. Agriculture. 2019;9:142. doi: 10.3390/agriculture9070142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santoyo G., Orozco-Mosqueda M.d.C., Govindappa M. Mechanisms of biocontrol and plant growth-promoting activity in soil bacterial species of Bacillus and Pseudomonas: A review. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2012;22:855–872. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2012.694413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang Y., Ran C., Chen L., Yin W., Liu Y., Chen C., Gao J. Purification and characterization of a novel antifungal flagellin protein from endophyte Bacillus methylotrophicus NJ13 against Ilyonectria robusta. Microorganisms. 2019;7:605. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maiyappan S., Amalraj E., Santhosh A., Peter A. Isolation, evaluation and formulation of selected microbial consortia for sustainable agriculture. J. Biofertil. Biopestic. 2010;2:2. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rajasekar S., Elango R. Effect of microbial consortium on plant growth and improvement of alkaloid content in Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) Curr. Bot. 2011;2:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghorbanpour M., Hatami M., Khavazi K. Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on antioxidant enzyme activities and tropane alkaloid production of Hyoscyamus niger under water deficit stress. Turkish J. Biol. 2013;37:350–360. doi: 10.3906/biy-1209-12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maggini V., Mengoni A., Bogani P., Firenzuoli F., Fani R. Promoting model systems of microbiota–medicinal plant interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mishra J., Fatima T., Arora N.K. Role of Secondary Metabolites from Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria in Combating Salinity Stress. In: Egamberdieva D., Ahmad P., editors. Plant Microbiome: Stress Response. Springer; Singapore: 2018. pp. 127–163. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kannojia P., Choudhary K.K., Srivastava A.K., Singh A.K. Chapter Four—PGPR Bioelicitors: Induced Systemic Resistance (isr) and Proteomic Perspective on Biocontrol. In: Singh A.K., Kumar A., Singh P.K., editors. PGPR Amelioration in Sustainable Agriculture. Woodhead Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2019. pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Narendra Babu A., Jogaiah S., Ito S.I., Kestur Nagaraj A., Tran L.S.P. Improvement of growth, fruit weight and early blight disease protection of tomato plants by rhizosphere bacteria is correlated with their beneficial traits and induced biosynthesis of antioxidant peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase. Plant Sci. 2015;231:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berger B., Brock A.K., Ruppel S. Nitrogen supply influences plant growth and transcriptional responses induced by Enterobacter radicincitans in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Soil. 2013;370:641–652. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1633-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou L., Tang K., Guo S. The plant growth-promoting fungus (PGPF) Alternaria sp. A13 markedly enhances Salvia miltiorrhiza root growth and active ingredient accumulation under greenhouse and field conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:270. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baiyee B., Ito S.I., Sunpapao A. Trichoderma asperellum T1 mediated antifungal activity and induced defense response against leaf spot fungi in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019;106:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2018.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.El-Sharkawy H.H.A., Abo-El-Wafa T.S.A., Ibrahim S.A.A. Biological control agents improve the productivity and induce the resistance against downy mildew of grapevine. J. Plant Pathol. 2018;100:33–42. doi: 10.1007/s42161-018-0007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.El-Sharkawy H.H.A., Rashad Y.M., Ibrahim S.A. Biocontrol of stem rust disease of wheat using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma spp. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018;103:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2018.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jaroszuk-Scisel J., Tyskiewicz R., Nowak A., Ozimek E., Majewska M., Hanaka A., Tyskiewicz K., Pawlik A., Janusz G. Phytohormones (auxin, gibberellin) and ACC deaminase in vitro synthesized by the mycoparasitic Trichoderma DEMTkZ3A0 strain and changes in the level of auxin and plant resistance markers in wheat seedlings inoculated with this strain conidia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:4923. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pretscher J., Fischkal T., Branscheidt S., Jäger L., Kahl S., Schlander M., Thines E., Claus H. Yeasts from different habitats and their potential as biocontrol agents. Fermentation. 2018;4:31. doi: 10.3390/fermentation4020031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun C., Lin M., Fu D., Yang J., Huang Y., Zheng X., Yu T. Yeast cell wall induces disease resistance against Penicillium expansum in pear fruit and the possible mechanisms involved. Food Chem. 2018;241:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang S., Xu B., Gan Y. Seed treatment with Trichoderma longibrachiatum T6 promotes wheat seedling growth under NaCl stress through activating the enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant defense systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3729. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdelrahman M., Abdel-Motaal F., El-Sayed M., Jogaiah S., Shigyo M., Ito S.I., Tran L.S.P. Dissection of Trichoderma longibrachiatum-induced defense in onion (Allium cepa L.) against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepa by target metabolite profiling. Plant Sci. 2016;246:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jogaiah S., Abdelrahman M., Tran L.S.P., Shin-ichi I. Characterization of rhizosphere fungi that mediate resistance in tomato against bacterial wilt disease. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:3829–3842. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jogaiah S., Shetty H.S., Ito S.I., Tran L.S.P. Enhancement of downy mildew disease resistance in pearl millet by the G_app7 bioactive compound produced by Ganoderma applanatum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;105:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu Z., Du S., Ren Y., Liu Y. Biocontrol ability of killer yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) isolated from wine against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides on grape. J. Basic Microb. 2018;58:60–67. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201700264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stürmer S.L., Bever J.D., Morton J.B. Biogeography of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota): a phylogenetic perspective on species distribution patterns. Mycorrhiza. 2018;28:587–603. doi: 10.1007/s00572-018-0864-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spagnoletti F., Carmona M., Gómez N.E.T., Chiocchio V., Lavado R.S. Arbuscular mycorrhiza reduces the negative effects of M. phaseolina on soybean plants in arsenic-contaminated soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017;121:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.MacLean A.M., Bravo A., Harrison M.J. Plant signaling and metabolic pathways enabling arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell. 2017;29:2319–2335. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cely M.V.T., de Oliveira A.G., de Freitas V.F., de Luca M.B., Barazetti A.R., dos Santos I.M.O., Gionco B., Garcia G.V., Prete C.E.C., Andrade G. Inoculant of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Rhizophagus clarus) increase yield of soybean and cotton under field conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:720. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li H., Chen X.W., Wong M.H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reduced the ratios of inorganic/organic arsenic in rice grains. Chemosphere. 2016;145:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang X., Wang L., Ma F., Yang J., Su M. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation on carbon and nitrogen distribution and grain yield and nutritional quality in rice (Oryza sativa L.) J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017;97:2919–2925. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bamberg S.M., Ramos S.J., Carneiro M.A.C., Siqueira J.O. Effects of selenium (Se) application and arbuscular mycorrhizal (AMF) inoculation on soybean (‘Glycine max’) and forage grass (‘Urochloa decumbens’) development in oxisol. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2019;13:380. doi: 10.21475/ajcs.19.13.03.p1245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu Z., Li Y., Ma L., Wei H., Zhang J., He X., Tian C. Coordinated regulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and soybean MAPK pathway genes improved mycorrhizal soybean drought tolerance. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014;28:408–419. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-14-0251-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jafari M., Yari M., Ghabooli M., Sepehri M., Ghasemi E., Jonker A. Inoculation and co-inoculation of alfalfa seedlings with root growth promoting microorganisms (Piriformospora indica, Glomus intraradices and Sinorhizobium meliloti) affect molecular structures, nutrient profiles and availability of hay for ruminants. Anim. Nutr. 2018;4:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gramisci B.R., Lutz M.C., Lopes C.A., Sangorrín M.P. Enhancing the efficacy of yeast biocontrol agents against postharvest pathogens through nutrient profiling and the use of other additives. Biol. Control. 2018;121:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chandra S., Singh B.K. Trichoderma spp.: As potential bio-control agents (BCAs) against fungal plant pathogens. Indian J. Life Sci. 2016;5:105. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elsen A., Gervacio D., Swennen R., De Waele D. AMF-induced biocontrol against plant parasitic nematodes in Musa sp.: A systemic effect. Mycorrhiza. 2008;18:251–256. doi: 10.1007/s00572-008-0173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Han J., Sun L., Dong X., Cai Z., Sun X., Yang H., Wang Y., Song W. Characterization of a novel plant growth-promoting bacteria strain Delftia tsuruhatensis HR4 both as a diazotroph and a potential biocontrol agent against various plant pathogens. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;28:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cabot C., Bosch R., Martos S., Poschenrieder C., Perelló A. Salinity is a prevailing factor for amelioration of wheat blast by biocontrol agents. Biol. Control. 2018;125:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Siahmoshteh F., Siciliano I., Banani H., Hamidi-Esfahani Z., Razzaghi-Abyaneh M., Gullino M.L., Spadaro D. Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens in the control of Aspergillus parasiticus growth and aflatoxins production on pistachio. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017;254:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xie K., Guo L., Bai Y., Liu W., Yan J., Bucher M. Microbiomics and plant health: an interdisciplinary and international workshop on the plant microbiome. Mol. Plant. 2019;12:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wei Z., Jousset A. Plant breeding goes microbial. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:555–558. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bai Y., Müller D.B., Srinivas G., Garrido-Oter R., Potthoff E., Rott M., Dombrowski N., Münch P.C., Spaepen S., Remus-Emsermann M., et al. Functional overlap of the Arabidopsis leaf and root microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:364–369. doi: 10.1038/nature16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knee E.M., Gong F.C., Gao M., Teplitski M., Jones A.R., Foxworthy A., Mort A.J., Bauer W.D. Root mucilage from pea and its utilization by rhizosphere bacteria as a sole carbon source. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:775–784. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jones D.L., Nguyen C., Finlay R.D. Carbon flow in the rhizosphere: carbon trading at the soil–root interface. Plant Soil. 2009;321:5–33. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-9925-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rudrappa T., Czymmek K.J., Paré P.W., Bais H.P. Root-secreted malic acid recruits beneficial soil bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1547. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.127613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tian L., Shi S., Ma L., Nasir F., Li X., Tran L.S.P., Tian C. Co-evolutionary associations between root-associated microbiomes and root transcriptomes in wild and cultivated rice varieties. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;128:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ha S., Vankova R., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K., Tran L.S.P. Cytokinins: metabolism and function in plant adaptation to environmental stresses. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jalali J., Gaudin P., Capiaux H., Ammar E., Lebeau T. Isolation and screening of indigenous bacteria from phosphogypsum-contaminated soils for their potential in promoting plant growth and trace elements mobilization. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;260:110063. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Goswami D., Thakker J.N., Dhandhukia P.C. Portraying mechanics of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016;2:1127500. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2015.1127500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.French K.E. Engineering mycorrhizal symbioses to alter plant metabolism and improve crop health. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1403. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ezawa T., Saito K. How do arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi handle phosphate? New insight into fine-tuning of phosphate metabolism. New Phytol. 2018;220:1116–1121. doi: 10.1111/nph.15187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gans J., Wolinsky M., Dunbar J. Computational improvements reveal great bacterial diversity and high metal toxicity in soil. Science. 2005;309:1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1112665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Berg G., Smalla K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;68:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lundberg D.S., Lebeis S.L., Paredes S.H., Yourstone S., Gehring J., Malfatti S., Tremblay J., Engelbrektson A., Kunin V., Rio T.G.d., et al. Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature. 2012;488:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Basha S.J., Basavarajappa R., Shimalli G., Babalad H. Soil microbial dynamics and enzyme activities as influenced by organic and inorganic nutrient management in vertisols under aerobic rice cultivation. J. Environ. Biol. 2017;38:131. doi: 10.22438/jeb/38/1/MS-205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li R., Tao R., Ling N., Chu G. Chemical, organic and bio-fertilizer management practices effect on soil physicochemical property and antagonistic bacteria abundance of a cotton field: implications for soil biological quality. Soil Tillage Res. 2017;167:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2016.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang X., Tang C., Severi J., Butterly C.R., Baldock J.A. Rhizosphere priming effect on soil organic carbon decomposition under plant species differing in soil acidification and root exudation. New Phytol. 2016;211:864–873. doi: 10.1111/nph.13966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ma X., Zarebanadkouki M., Kuzyakov Y., Blagodatskaya E., Pausch J., Razavi B.S. Spatial patterns of enzyme activities in the rhizosphere: Effects of root hairs and root radius. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018;118:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Meena V.S., Meena S.K., Verma J.P., Kumar A., Aeron A., Mishra P.K., Bisht J.K., Pattanayak A., Naveed M., Dotaniya M.L. Plant beneficial rhizospheric microorganism (PBRM) strategies to improve nutrients use efficiency: A review. Ecol. Eng. 2017;107:8–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.06.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang X., Zhang R., Gao J., Wang X., Fan F., Ma X., Yin H., Zhang C., Feng K., Deng Y. Thirty-one years of rice-rice-green manure rotations shape the rhizosphere microbial community and enrich beneficial bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017;104:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Simon J., Dannenmann M., Pena R., Gessler A., Rennenberg H. Nitrogen nutrition of beech forests in a changing climate: Importance of plant-soil-microbe water, carbon, and nitrogen interactions. Plant Soil. 2017;418:89–114. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3293-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hestrin R., Hammer E.C., Mueller C.W., Lehmann J. Synergies between mycorrhizal fungi and soil microbial communities increase plant nitrogen acquisition. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:233. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0481-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shi S., Tian L., Nasir F., Bahadur A., Batool A., Luo S., Yang F., Wang Z., Tian C. Response of microbial communities and enzyme activities to amendments in saline-alkaline soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019;135:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kim K.H., Kabir E., Jahan S.A. Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;575:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gomiero T. Food quality assessment in organic vs. conventional agricultural produce: Findings and issues. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018;123:714–728. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tian L., Shi S., Ji L., Nasir F., Ma L., Tian C. Effect of the biocontrol bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens on the rhizosphere in ginseng plantings. Int. Microbiol. 2018;21:153–162. doi: 10.1007/s10123-018-0015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Siciliano S.D., Fortin N., Mihoc A., Wisse G., Labelle S., Beaumier D., Ouellette D., Roy R., Whyte L.G., Banks M.K., et al. Selection of specific endophytic bacterial genotypes by plants in response to soil contamination. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2001;67:2469–2475. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2469-2475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Banfield C.C., Pausch J., Kuzyakov Y., Dippold M.A. Microbial processing of plant residues in the subsoil –The role of biopores. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018;125:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.De León-Lorenzana A.S., Delgado-Balbuena L., Domínguez-Mendoza C.A., Navarro-Noya Y.E., Luna-Guido M., Dendooven L. Soil salinity controls relative abundance of specific bacterial groups involved in the decomposition of maize plant residues. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018;6:51. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lian T., Wang G., Yu Z., Li Y., Liu X., Jin J. Carbon input from 13C-labelled soybean residues in particulate organic carbon fractions in a Mollisol. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2016;52:331–339. doi: 10.1007/s00374-015-1080-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yang X., Meng J., Lan Y., Chen W., Yang T., Yuan J., Liu S., Han J. Effects of maize stover and its biochar on soil CO2 emissions and labile organic carbon fractions in Northeast China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017;240:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2017.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kantola I.B., Masters M.D., DeLucia E.H. Soil particulate organic matter increases under perennial bioenergy crop agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017;113:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Crews T., Rumsey B. What agriculture can learn from native ecosystems in building soil organic matter: A review. Sustainability. 2017;9:578. doi: 10.3390/su9040578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cornejo P., Meier S., García S., Ferrol N., Durán P., Borie F., Seguel A. Contribution of inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to the bioremediation of a copper contaminated soil using Oenothera picensis. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nut. 2017;17:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhou C., Li F., Xie Y., Zhu L., Xiao X., Ma Z., Wang J. Involvement of abscisic acid in microbe-induced saline-alkaline resistance in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017;12:e1367465. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2017.1367465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Musilova L., Ridl J., Polivkova M., Macek T., Uhlik O. Effects of secondary plant metabolites on microbial populations: changes in community structure and metabolic activity in contaminated environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1205. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hardoim P.R., van Overbeek L.S., Elsas J.D. Properties of bacterial endophytes and their proposed role in plant growth. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ortega R.A., Mahnert A., Berg C., Müller H., Berg G. The plant is crucial: specific composition and function of the phyllosphere microbiome of indoor ornamentals. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016;92:173. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liu D., Sun H., Ma H. Deciphering microbiome related to rusty roots of Panax ginseng and evaluation of antagonists against pathogenic Ilyonectria. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1350. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Stone B.W., Weingarten E.A., Jackson C.R. The role of the phyllosphere microbiome in plant health and function. Annu. Plant Rev. Online. 2018;6:533–556. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Vacher C., Hampe A., Porté A.J., Sauer U., Compant S., Morris C.E. The phyllosphere: microbial jungle at the plant–climate interface. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016;47:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-121415-032238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bringel F., Couée I. Pivotal roles of phyllosphere microorganisms at the interface between plant functioning and atmospheric trace gas dynamics. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:486. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.AbuQamar S., Moustafa K., Tran L.S. Mechanisms and strategies of plant defense against Botrytis cinerea. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017;37:262–274. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2016.1271767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Farrar K., Bryant D., Cope-Selby N. Understanding and engineering beneficial plant–microbe interactions: plant growth promotion in energy crops. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12:1193–1206. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Truyens S., Weyens N., Cuypers A., Vangronsveld J. Bacterial seed endophytes: genera, vertical transmission and interaction with plants. Env. Microbiol. Rep. 2015;7:40–50. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bacon C.W., Hinton D.M. Plant-Associated Bacteria. Gnanamanickam SS. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2006. Bacterial endophytes: The Endophytic Niche, Its Occupants, and Its Utility; pp. 155–194. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhao Y., Xiong Z., Wu G., Bai W., Zhu Z., Gao Y., Parmar S., Sharma V.K., Li H. Fungal endophytic communities of two wild rosa varieties with different powdery mildew susceptibilities. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2462. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Borah M., Das S., Baruah H., Boro R.C., Barooah M. Diversity of culturable endophytic bacteria from wild and cultivated rice showed potential plant growth promoting activities. bioRxiv. 2018 doi: 10.1101/310797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Murphy B.R., Hodkinson T.R., Doohan F.M. Endophytic Cladosporium strains from a crop wild relative increase grain yield in barley. Biol. Environ. 2018;118:147–156. doi: 10.3318/bioe.2018.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sawers R.J.H., Ramirez-Flores M.R., Olalde-Portugal V., Paszkowski U. The impact of domestication and crop improvement on arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in cereals: Insights from genetics and genomics. New Phytol. 2018;220:1135–1140. doi: 10.1111/nph.15152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Majeed A., Muhammad Z., Ahmad H. Plant growth promoting bacteria: role in soil improvement, abiotic and biotic stress management of crops. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;37:1599–1609. doi: 10.1007/s00299-018-2341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Martín-Robles N., Lehmann A., Seco E., Aroca R., Rillig M.C., Milla R. Impacts of domestication on the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis of 27 crop species. New Phytol. 2018;218:322–334. doi: 10.1111/nph.14962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Chiapusio G., Sánchez A.M., Reigosa M.J., González L., Pellissier F. Do germination indices adequately reflect allelochemical effects on the germination process? J. Chem. Ecol. 1997;23:2445–2453. doi: 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000006658.27633.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Vivanco J.M., Bais H.P., Stermitz F.R., Thelen G.C., Callaway R.M. Biogeographical variation in community response to root allelochemistry: novel weapons and exotic invasion. Ecol. Lett. 2004;7:285–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00576.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Niro E., Marzaioli R., De Crescenzo S., D’Abrosca B., Castaldi S., Esposito A., Fiorentino A., Rutigliano F.A. Effects of the allelochemical coumarin on plants and soil microbial community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016;95:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]