Abstract

Ikaros is a DNA-binding protein that regulates gene expression and functions as a tumor suppressor in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). The full cohort of Ikaros target genes have yet to be identified. Here, we demonstrate that Ikaros directly regulates expression of the small GTPase, Rab20. Using ChIP-seq and qChIP we assessed Ikaros binding and the epigenetic signature at the RAB20 promoter. Expression of Ikaros, CK2, and RAB20 was determined by qRT-PCR. Overexpression of Ikaros was achieved by retroviral transduction, whereas shRNA was used to knockdown Ikaros and CK2. Regulation of transcription from the RAB20 promoter was analyzed by luciferase reporter assay. The results showed that Ikaros binds the RAB20 promoter in B-ALL. Gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments demonstrated that Ikaros represses RAB20 transcription via chromatin remodeling. Phosphorylation by CK2 kinase reduces Ikaros’ affinity toward the RAB20 promoter and abolishes its ability to repress RAB20 transcription. Dephosphorylation by PP1 phosphatase enhances both Ikaros’ DNA-binding affinity toward the RAB20 promoter and RAB20 repression. In conclusion, the results demonstrated opposing effects of CK2 and PP1 on expression of Rab20 via control of Ikaros’ activity as a transcriptional regulator. A novel regulatory signaling network in B-cell leukemia that involves CK2, PP1, Ikaros, and Rab20 is identified.

Keywords: Ikaros, CK2, PP1, RAB20, B-ALL

1. Introduction

IKZF1 encodes the 519 amino acid DNA-binding, zinc-finger protein, Ikaros [1,2,3,4]. Ikaros plays a crucial role in regulating normal lymphopoiesis [3,5,6,7] and functions as a tumor suppressor [8]. Germline mutations or deletions that compromise Ikaros activity are associated with the development of B-cell leukemia [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], T-cell leukemia, lymphoma [8,17], and primary immunodeficiency [18,19]. Ikaros was shown to regulate myeloid cell proliferation [20,21,22,23,24] and somatic Ikaros alterations are associated with myeloproliferative disorders [25,26,27,28]. Somatic deletion of a single Ikaros allele is associated with pediatric leukemias with resistance to treatment, high relapse rate, and poor prognosis [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Ikaros mediates its tumor suppressive effects through sequence-specific DNA binding and recruitment of histone remodeling complexes such as NuRD, via direct binding to Mi-2 [37,38,39,40]. Ikaros also directly interacts with and recruits HDAC1 and HDAC2 to the promoters of its target genes [38,41]. These data suggest that Ikaros exerts its tumor suppressive effect through chromatin remodeling at the regulatory elements of its gene targets [42,43,44].

In addition to genetic inactivation, Ikaros activity can be regulated by post-translational phosphorylation and SUMOylation [45,46]. The effect of Ikaros phosphorylation by pro-oncogenic casein kinase II (CK2) has been extensively studied [45]. CK2 is a pleotropic serine/threonine kinase that is overexpressed in multiple cancers including leukemia [47,48]. Studies showed that CK2 directly phosphorylates multiple residues throughout the Ikaros protein [49]. Functional experiments using phosphomimetic and phosphoresistant Ikaros mutants showed that phosphorylation at CK2 phosphosites severely reduces Ikaros’ ability to bind DNA and, thus, in functional inactivation of the Ikaros protein [49]. Pharmacological inhibition of CK2 with small molecule CK2 inhibitors restores Ikaros’ DNA-binding ability along with its tumor suppressor activity and causes leukemia cell cytotoxicity in high-risk patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [50]. This discovery highlighted CK2 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for high-risk pediatric leukemia [51,52,53].

Ikaros directly interacts with protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) via a PP1-consensus binding site at Ikaros’ C-terminal end [54]. PP1 is a serine/threonine phosphatase that regulates cell division and cell metabolism [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Ikaros is dephosphorylated by PP1, which reverses the effect of CK2-mediated phosphorylation [54,63]. Mutations at Ikaros’ PP1-interaction site, as well as pharmacological inhibition of PP1, result in Ikaros hyperphosphorylation, severely reduced Ikaros DNA-binding ability, and the loss of Ikaros’ pericentromeric localization. Ikaros’ inability to interact with PP1 also results in increased degradation of Ikaros via the ubiquitin pathway [54]. These data suggest that the balance between CK2 and PP1 plays a crucial role in regulating Ikaros activity and that a perturbation of this balance results in impaired Ikaros function [64,65].

Identification of the genes whose transcription and overall expression are directly regulated by Ikaros provided insights into Ikaros’ function as a regulator of hematopoiesis and a tumor suppressor [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. These studies uncovered an Ikaros regulatory network that controls normal hematopoiesis and malignant transformation [74,75,76,77,78]. Here, we report that Ikaros regulates the expression of the small GTPase Rab20 in leukemia, and that CK2 and PP1 regulate Ikaros’ ability to repress RAB20 transcription. The results suggested that Ikaros exerts its tumor suppressor activity by regulating RAB20 expression and demonstrate the role of CK2 and PP1 in regulating the Rab20 signaling pathway.

2. Results

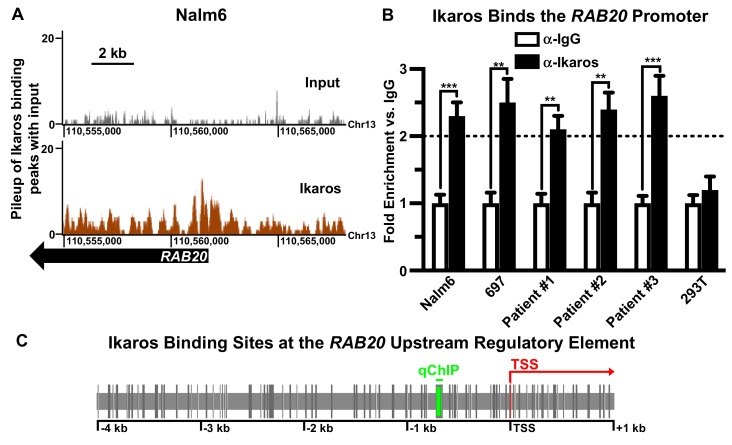

2.1. Ikaros Binds to the RAB20 Promoter in B-ALL Cells

Determination of global, genome-wide Ikaros DNA occupancy was performed using chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with next generation sequencing (ChIP-seq). This was performed in the human B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) cell line Nalm6. Analysis of ChIP-seq data identified 5788 prospective target genes regulated by Ikaros in Nalm6 cells [50], including a strong Ikaros binding peak at the promoter sequence of the RAB20 gene (Figure 1A). RAB20 was selected for further analysis for several reasons: (1) Analysis of Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter by ChIP-seq revealed a strong peak, with the center of the peak located in very close proximity (−104 bp) to the transcriptional start site (TSS) of the RAB20 gene. This suggests that Ikaros binding likely regulates transcription of RAB20; (2) Rab20 most likely has oncogenic activity in colorectal cancer [79,80,81], and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [82,83]. Ikaros functions as a tumor suppressor in these malignancies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,81,84]. (3) Rab20 function is associated with increased immune response [85,86,87] and in immune activation of macrophages [88,89]. Ikaros functions as a suppressor of TCR signaling and in macrophages [90,91,92,93]. (4) The potential role of Ikaros in regulating GTPase signaling is unknown and, in general, the mechanisms that regulate transcription of Rab GTPase genes are not well studied; and (5) although Rab20 was suggested to act as an oncogene in various malignancies [79,80,82,94,95,96], its role in B-ALL is unknown. Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter suggests a possible role of Rab20 in B-ALL. Demonstrating the involvement of the CK2–Ikaros axis in regulating RAB20 expression would represent a new class of genes, GTPases, regulated by Ikaros and provide insight into the cross-talk of signaling pathways in leukemia. Ikaros binding to the promoter of RAB20 was further confirmed by quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) in human B-ALL cell lines and primary B-ALL cells (Figure 1B, panels 1–5). Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter was not detected in 293T cells, which do not express Ikaros (Figure 1B, panel 6). A metanalysis of previous ChIP-seq data in patient-derived human pre-B ALL xenograft LAX2 cells, identified strong Ikaros binding at the RAB20 promoter (Figure S1). A metanalysis of a publicly available B-ALL gene expression dataset identified an inverse correlation between IKZF1 and RAB20 expression that was statistically significant (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Ikaros binding in the RAB20 URE. (A) ChIP-seq signal map for Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter in the Nalm6 B-ALL cell line. (B) qChIP analysis of Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter in human B-ALL cell lines, primary human B-ALL cells, and Ikaros-null HEK293T cells. The graphed data is the mean ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments. (C) Schematic diagram of Ikaros consensus binding motifs (–GGGA– and –GGAA–) in the human RAB20 upstream regulatory element (grey vertical lines). The green line marks the site that was analyzed by qChIP and the TSS is marked by the red arrow.

The RAB20 gene encodes the Rab20 small GTPase, a protein shown to be involved in regulating cellular proliferation, cell metabolism, and inflammation. DNA sequence analysis of the RAB20 promoter identified a strong Ikaros consensus binding site located in close proximity to the transcriptional start site of RAB20 and within the Ikaros peak detected by ChIP-seq. The RAB20 promoter contains a large number of core Ikaros consensus DNA binding sequences (–GGGA– or –GGAA–) in close proximity to each other (Figure 1C). Since Ikaros binds with higher affinity to DNA sequences that contain two core consensus Ikaros binding sites within 40 bp, these data indicated that the RAB20 promoter has several high-affinity Ikaros binding sites. This suggests that Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter has strong functional significance in cellular metabolism.

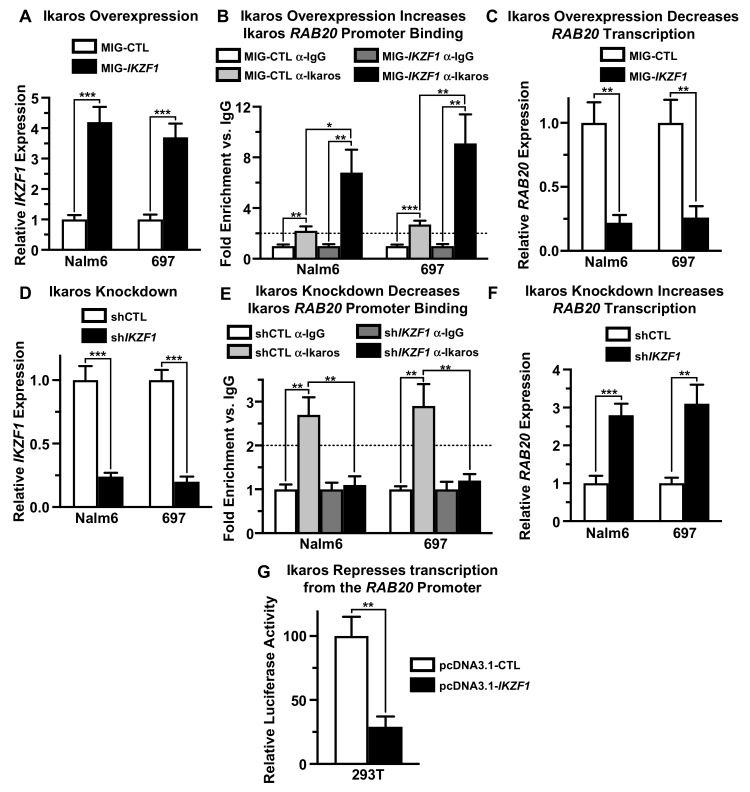

2.2. Ikaros Represses Transcription of the RAB20 Gene

To establish the functional significance of Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter, we evaluated the effect of Ikaros overexpression and knockdown on RAB20 expression in the human B-ALL cell lines Nalm6 and 697. Overexpression of Ikaros in Nalm6 and 697 cells was achieved by retroviral transduction, using retrovirus that co-expresses Ikaros and green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a marker. Transduction with a retrovirus that does not contain the Ikaros gene was used as a negative control. Quantitative PCR analysis (qPCR) showed that retroviral Ikaros transduction results in increased Ikaros expression compared to the negative control in both Nalm6 and 697 cells (Figure 2A). Increased Ikaros expression was associated with increased Ikaros binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene by qChIP compared with the negative control (Figure 2B). Increased Ikaros binding to the RAB20 gene was associated with strong transcriptional repression of RAB20 per qPCR compared with the negative control (Figure 2C). These data suggest that Ikaros transcriptionally represses the RAB20 gene.

Figure 2.

Ikaros represses RAB20 transcription. (A) Human B-ALL cell lines were transduced with empty vector (MIG-CTL) or Ikaros (MIG-IKZF1) and relative IKZF1 expression was determined by qRT-PCR. (B) qChIP was used to determine Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter after Ikaros overexpression. (C) Ikaros overexpression resulted in a decrease in RAB20 expression as determined by qRT-PCR. (D) Human B-ALL cell lines were transduced with scrambled shRNA (shCTL) and shRNA targeting IKZF1 (shIKZF1) and relative Ikaros expression determined using qRT-PCR. (E) qChIP was used to determine Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter after Ikaros knockdown. (F) Ikaros knockdown resulted in an increase in RAB20 expression as determined by qRT-PCR. (G) The effect of Ikaros on transcription from the URE of human RAB20 using a luciferase reporter assay following transfection with control vector (pcDNA3.1-CTL) or human Ikaros (pcDNA3.1-IKZF1). The graphed data are the mean ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments.

Ikaros loss-of-function was achieved using Ikaros shRNA. Ikaros knock-down with shRNA resulted in reduced Ikaros expression in Nalm6 and 697 cells compared with negative controls (Figure 2D). Reduced Ikaros expression was associated with diminished Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter, as evidenced by qChIP (Figure 2E). Loss of Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter was associated with increased expression of RAB20 in both Nalm6 and 697 B-ALL cells (Figure 2F). Together with data from experiments described in Figure 2A–C, these results demonstrated that Ikaros negatively regulates expression of RAB20 in B-ALL cells by acting as a transcriptional repressor at the RAB20 promoter.

We tested whether Ikaros can directly repress transcription of the RAB20 gene using the luciferase reporter assay. 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmid expressing the luciferase gene under control of the RAB20 promoter along with the Ikaros-expressing plasmid or the empty vector (negative control). Luciferase expression was determined using the luciferase reporter assay. The results showed that co-transfection with Ikaros significantly reduces transcription from the RAB20 promoter compared with the negative control (Figure 2G). These results demonstrated that Ikaros can repress transcription by directly binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene.

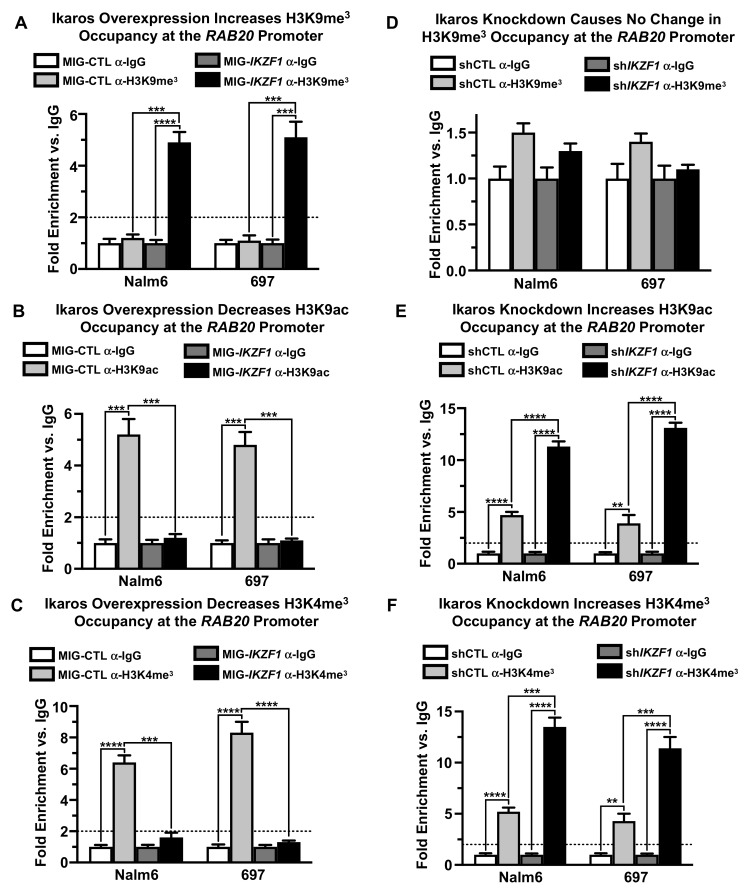

2.3. Ikaros Represses RAB20 Transcription via Chromatin Remodeling

Next, we sought to determine the mechanism through which Ikaros represses transcription of RAB20 in B-ALL. One of the main mechanisms through which Ikaros represses its target genes involves chromatin remodeling and the formation of facultative heterochromatin [97]. We determined how Ikaros gain-of-function and loss-of-function affect the chromatin signature at the RAB20 promoter in Nalm6 and 697 cells.

H3K9ac and H3K4me3 are the epigenetic markers of open and active chromatin, whereas H3K9me3 is a marker of closed and repressive chromatin. We found that overexpression of Ikaros by retroviral transduction results in enrichment in H3K9me3 histone modification markers at the promoter of the RAB20 gene in both Nalm6 and 697 cells compared with the negative control (Figure 3A). This was also associated with a loss of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 markers at the RAB20 promoter (Figure 3B,C). Ikaros knockdown with shRNA resulted in an absence of the H3K9me3 marker (Figure 3D) at the promoter of the RAB20 gene along with increased H3K9ac and H3K4me3 markers (Figure 3E,F) at the RAB20 promoter.

Figure 3.

Ikaros increases the occupancy of closed chromatin markers at the RAB20 promoter. (A–C) qChIP was used to determine relative H3K9me3, H3K9ac, and H3K4me3 occupancy at the RAB20 promoter after Ikaros overexpression (MIG-IKZF1) compared with the control (MIG-CTL). (D–F) qChIP was used to determine relative H3K9me3, H3K9ac, and H3K4me3 occupancy at the RAB20 promoter after Ikaros knockdown (shIKZF1) compared with a scrambled control (shCTL). The graphed data are the mean ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments.

Additional analyses showed no enrichment of HDAC1 histone deacetylase at the RAB20 promoter and that alterations of Ikaros expression do not affect HDAC1 occupancy around the RAB20 transcriptional start site (data not shown). These results suggested that HDAC1 is not involved in the regulation of RAB20 transcription.

Overall, these results suggested that Ikaros represses transcription of the RAB20 gene by inducing the formation of repressive chromatin at the RAB20 promoter via an HDAC1-independent mechanism.

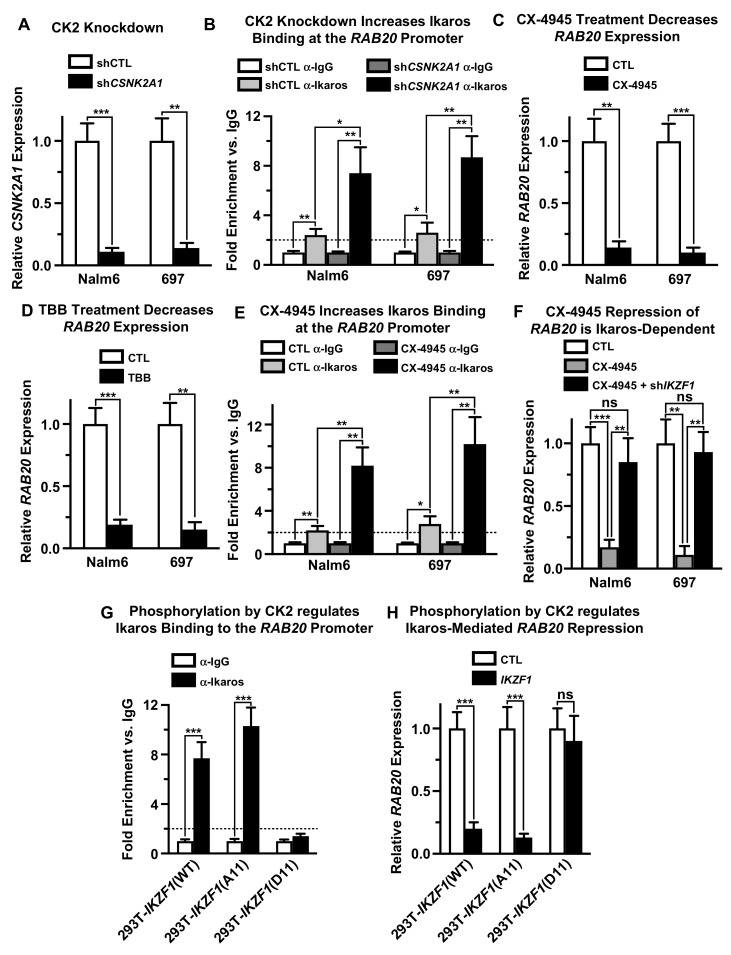

2.4. Casein Kinase II (CK2) Regulates Ikaros’ Ability to Repress RAB20 Transcription

Casein kinase II (CK2) directly phosphorylates Ikaros at multiple evolutionarily-conserved serine and threonine residues and that phosphorylation by CK2 can regulate Ikaros’ DNA-binding affinity and its ability to function as a transcriptional regulator of its target genes [49]. We tested whether CK2 regulates Ikaros’ function as a transcriptional repressor of RAB20. Molecular inhibition of CK2 by knock-down with shRNA directed against the CK2 α catalytic subunit (CSNK2A1), resulted in reduced expression of CK2 (Figure 4A). This was associated with increased Ikaros binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene in both Nalm6 and 697 cells, as evidenced by qChIP (Figure 4B), and with profoundly reduced transcription of RAB20 in both cell lines (Figure 4C). Pharmacological inhibition of CK2 using its specific inhibitor, CX-4945, as well as with a structurally-different CK2 inhibitor, TBB, also resulted in a strong negative effect on RAB20 transcription in both B-ALL cell lines (Figure 4D). Treatment with CX-4945 resulted in increased Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter, as evidenced by the qChIP assay (Figure 4E). These data showed that CK2 inhibition negatively regulates RAB20 transcription and suggested that the mechanism of CK2-mediated repression of RAB20 involves transcriptional repression by Ikaros, along with the increased DNA binding of Ikaros to the promoter of the RAB20 gene.

Figure 4.

CK2 regulates Ikaros’ ability to repress RAB20 transcription. (A) Human B-ALL cell lines were transduced with scrambled shRNA (shCTL) and shRNA targeting CK2α (shCSNK2A1) and relative CSNK2A1 expression was determined using qRT-PCR. (B) qChIP was used to analyze Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter after CK2α knockdown (shCSNK2A1). (C,D) Human B-ALL cell lines were treated with pharmacological CK2 inhibitors CX-4945 and TBB, and RAB20 expression was analyzed using qRT-PCR. (E) qChIP was used to analyze Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter after treatment with CX-4945. (F) Human B-ALL cell lines were treated with CK2 inhibitor CX-4945 and transduced with shRNA targeting Ikaros (shIKZF1) and RAB20 expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (G) HEK293T cells were transduced with wild-type Ikaros (IKZF1-(WT)), Ikaros with phosphoresistant alanine mutations at CK2 phosphosites (IKZF1-(A11)), and Ikaros with phosphomimetic aspartate mutations at CK2 phosphosites (IKZF1-(D11)). qChIP was used to determine Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter. (H) qRT-PCR was used to determine RAB20 expression in HEK293T cells transduced with wild-type Ikaros (IKZF1-(WT)) and Ikaros phosphoresistant IKZF1-(A11) and phosphomimetic IKZF1-(D11) mutants at CK2 phosphosites. The graphed data are the mean ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments.

CK2 phosphorylates many proteins. We tested whether Ikaros activity is essential for CK2-mediated repression of RAB20 in human B-ALL cells. The results showed that knock-down of Ikaros with shRNA, abolishes CK2-induced transcriptional repression of the RAB20 gene in both Nalm6 and 697 cells (Figure 4F). These results demonstrated that negative regulation of RAB20 expression by CK2 inhibition occurs via Ikaros transcriptional repression activity and, thus, Ikaros activity is critical for CK2-mediated regulation of RAB20 transcription.

Next, we tested whether phosphorylation of the known CK2 phosphosites on the Ikaros protein regulates its ability to repress transcription of the RAB20 gene. For these experiments, we used Ikaros phosphomimetic and phosphoresistant mutants that were previously described [49]. The Ikaros phosphomimetic mutant (IKZF1-D11) has 11 serine or threonine residues that are known to be phosphorylated in vivo by CK2, mutated into aspartate. In contrast, the Ikaros phosphoresistant mutant (IKZF1-A11) has the same 11 serine of threonine residues mutated into alanine. 293T cells that do not express endogenous Ikaros were transfected with wild-type Ikaros or with Ikaros phosphomimetic or phosphoresistant mutants and the DNA binding of Ikaros proteins to the promoter of the endogenous RAB20 gene and the effect of each protein on RAB20 transcription was analyzed by qChIP and qRT-PCR, respectively. The results showed that both wild-type Ikaros (IKZF1-WT) and its phosphoresistant mutant (IKZF1-A11) bind to the RAB20 promoter with high affinity in 293T cells, although the DNA-binding affinity of IKZF1-A11 appears to be somewhat stronger compared to that of the wild-type Ikaros (Figure 4G). However, the Ikaros phosphomimetic mutant (IKZF1-D11) bound poorly to the promoter of the RAB20 gene in 293T cells as measured by qChIP (Figure 4G). Both wild-type and the phosphoresistant Ikaros mutant (IKZF1-A11) resulted in repression of RAB20 gene transcription in 293T cells, whereas the Ikaros phosphomimetic mutant (IKZF1-D11) had no effect on the expression of the RAB20 genes, as measured by qRT-PCR (Figure 4H). These data demonstrated that CK2 regulates Ikaros’ ability to bind to the promoter of the RAB20 gene and transcriptionally repress its expression by directly phosphorylating Ikaros proteins on one or several serine/threonine residues. These results thus establish that RAB20 transcription is regulated by the CK2–Ikaros signaling axis.

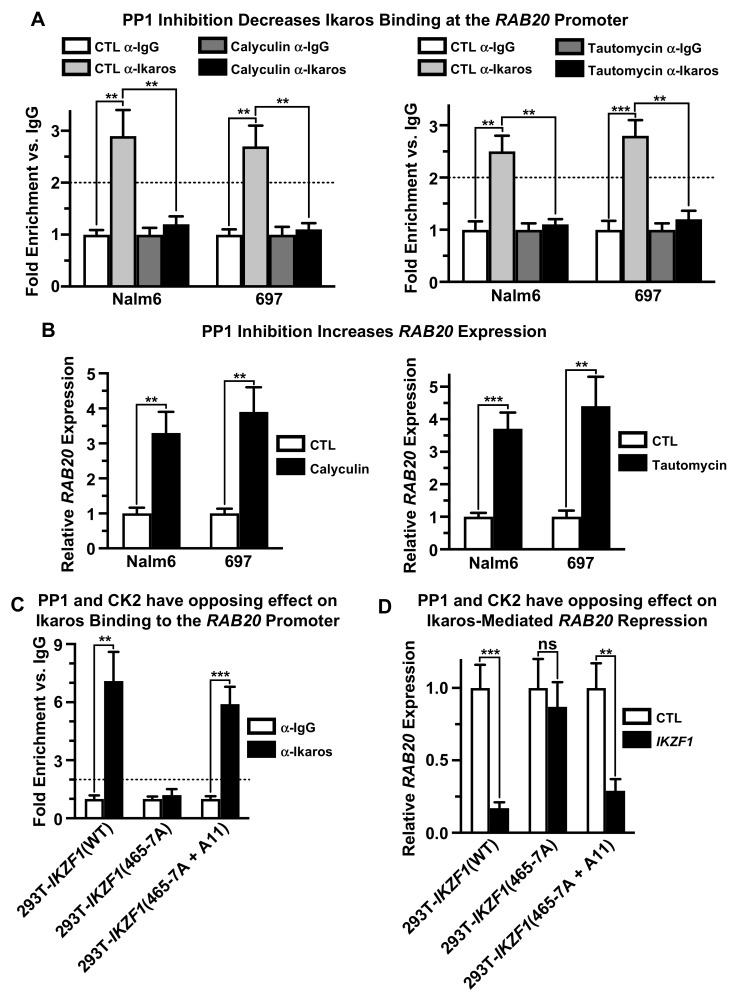

2.5. Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) Regulates Ikaros’ Function as Repressor of RAB20 Transcription

We tested the effect of phosphatases on Ikaros’ ability to repress transcription of the RAB20 gene. Treatment of both Nalm6 and 697 cells with a strong inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), calyculin, results in the loss of Ikaros binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene as measured by qChIP (Figure 5A, left panel). A similar effect was achieved when Nalm6 and 697 cells were treated with tautomycin, which is a highly selective inhibitor of PP1 (Figure 5A, right panel). Treatment with both calyculin and tautomycin resulted in increased transcription of the RAB20 gene in both Nalm6 and 697 cells, as measured by qRT-PCR (Figure 5B). These data showed that dephosphorylation of Ikaros is essential for its function as a transcriptional repressor of the RAB20 gene in B-ALL cells.

Figure 5.

PP1 regulates repression of RAB20 by Ikaros. (A) Human B-ALL cell lines were treated with pharmacological PP1 inhibitors calyculin and tautomycin. qChIP was used to determine Ikaros occupancy at the RAB20 promoter. (B) RAB20 expression was analyzed using qRT-PCR after PP1 inhibition with calyculin and tautomycin. (C) HEK293T cells were transduced with wild-type Ikaros (IKZF1(WT)), Ikaros with the mutated PP1 binding-site (IKZF1(565-7A)), and Ikaros with the PP1 binding-site mutated and phosphoresistant alanine mutations at CK2 phosphosites (IKZF1(465-7A + A11)). qChIP was used to determine Ikaros binding at the RAB20 promoter. (D) qRT-PCR was used to determine RAB20 expression in HEK293T cells transduced with wild-type Ikaros (IKZF1-(WT)) and mutated Ikaros (IKZF1-(465-7A) and IKZF1-(465-7A + A11)). The graphed data are the mean ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments.

Ikaros is a substrate for PP1. The Ikaros protein contains a consensus binding site for PP1, which is essential for Ikaros-PP1 interaction and for dephosphorylation of Ikaros by PP1 [54]. Since the treatment of B-ALL cells with a specific PP1 inhibitor, tautomycin, strongly affects Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter and repression of RAB20 transcription, we tested whether the interaction between Ikaros and PP1 affects the ability of Ikaros to repress RAB20. The wild-type Ikaros or the Ikaros mutant that contains alanine point mutations at amino acids 465 and 467 that disrupt Ikaros–PP1 interactions (IKZF1-465-7A) was transfected into 293T cells, and the effect of the Ikaros–PP1 interaction on Ikaros’ function in regulating RAB20 expression was analyzed. The results showed that inhibition of PP1 interaction with Ikaros (IKZF1-465-7A) results in the loss of Ikaros binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene compared to the wild type Ikaros, as measured by qChIP (Figure 5C panels 1 and 2). Unlike wild-type Ikaros, the IKZF1-465-7A mutant had no effect on RAB20 transcription (Figure 5D, panels 1 and 2). These data showed that PP1 regulates RAB20 expression, and that the direct interaction of Ikaros with PP1 is essential for Ikaros binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene and for repression of RAB20.

We tested whether dephosphorylation of the CK2 phosphosites on the Ikaros protein is critical for the effect of PP1 on RAB20 expression. The effect of an Ikaros mutant that is unable to interact with PP1 but which also has phosphoresistant mutations at CK2 phosphosites (IKZF1-465-7A+A11) was evaluated for its effect on RAB20 transcription. The results showed that phosphoresistant mutations at CK2 phosphosites restored the DNA-binding ability of the Ikaros mutant that did not interact with PP1 (Figure 5C, panel 3) as well as Ikaros’ function as a transcriptional repressor of the RAB20 gene (Figure 5D, panel 3). Together, these results demonstrated that direct dephosphorylation of CK2 phosphosites on Ikaros by PP1 is essential for Ikaros binding to the promoter of the RAB20 gene and its transcriptional repression. These data demonstrated that regulation of RAB20 transcription by Ikaros is regulated in opposing ways by CK2 and PP1.

3. Discussion

Ikaros’ role in hematopoiesis, immune response, and tumor suppression depends on its ability to regulate expression of its target genes. The gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments presented above demonstrated that Ikaros regulates expression of the RAB20 gene in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). Ikaros regulates RAB20 transcription both directly, as evidenced by the luciferase reporter assay, and via chromatin remodeling by inducing the formation of heterochromatin at the RAB20 promoter, characterized by the H3K9me3 repressive marker.

Rab20 belongs to the Rab family of over 60 small GTPase genes [98]. Proteins encoded by these genes are critical for regulating membrane trafficking [99] and vesicular transport in all cells in eukaryotes [100,101]. Numerous reports demonstrated the important role of the Rab20 protein in immune response [85,86,87]. Rab20 is highly expressed in macrophages, where it plays a role in phagosome biology [102,103] and regulation of endosomal morphology [88]. Expression of Rab20 in macrophages is positively regulated by the NF-κB pathway following mycoplasma infection [89], as well as by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) treatment [88], suggesting the role of Rab20 in immune activation of macrophages. Deregulation of RAB20 expression was associated with various types of human malignancies: RAB20 overexpression was pronounced in pancreatic cancer cell lines and in primary pancreatic carcinoma [94], in exocrine pancreatic carcinoma, and in preneoplastic pancreatic tissue compared with normal pancreatic cells [94]. RAB20 amplifications were strongly correlated with the presence of high-grade dysplastic colorectal adenomas, and aberrations of Rab20 were associated with high-risk colorectal adenomas [79]. Amplification of Rab20 was strongly correlated with adenoma recurrence and the presence of colorectal carcinomas [79], whereas overexpression of RAB20 was associated with colorectal carcinoma liver metastases [80]. Deregulation and a potential oncogenic role for Rab20 was reported in triple negative breast cancer [95] and in bladder cancer [96]. The potential role of Rab20 in leukemia is not well studied, although overexpression of RAB20 was observed in myelodysplastic syndrome [82]. Since Ikaros’ role in macrophage function [104,105,106], colorectal cancer [81], and MDS [83] was described previously, the data presented here suggested that Ikaros activity in these conditions might be mediated via regulation of RAB20 transcription. Ikaros’ role in regulating GTPases was previously unexplored, but the data presented here demonstrated the involvement of the CK2-Ikaros axis in regulating expression of the Rab20 GTPase in B-ALL. These data provide new insights into the cross-talk of signaling pathways in leukemia.

Ikaros is phosphorylated at multiple amino acids [107]. Phosphorylation was reported to regulate Ikaros’ DNA-binding affinity, which is essential for its function as a transcriptional regulator [107,108]. CK2 phosphorylates Ikaros at evolutionarily-conserved serine/threonine residues, and thus directly regulates Ikaros’ ability to bind promoters of its target genes, to localize to pericentromeric heterochromatin, and to function as a regulator of gene expression [64,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,109,110]. Increased expression of CK2 was associated with various types of leukemia as well as with other human malignancies. Overexpression of CK2 in leukemia results in reduced Ikaros DNA-binding affinity, and its function as a transcriptional regulator and tumor suppressor; thus, loss of Ikaros function due to CK2 overexpression has a leukemogenic effect [65,111]. The data presented in this manuscript demonstrate that CK2 is a critical regulator of Ikaros’ ability to bind the RAB20 promoter and control RAB20 transcription. Both molecular and pharmacological inhibition of CK2 as well as phosphoresistant mutations at CK2 phosphosites in the Ikaros protein enhanced Ikaros binding to the RAB20 promoter and transcriptional repression of Rab20. These results suggested that the CK2 signaling pathway can affect membrane trafficking in leukemia cells through regulation of Rab20 expression via Ikaros.

Protein phosphatase 1 can function as a tumor suppressor in human malignancies [58,59,60,61]. PP1 was reported to directly bind the PP1 consensus binding site at the C-terminal end of the Ikaros protein. The role of PP1 in the control of Ikaros function in regulating gene expression has not been extensively studied, and the transcription of only one gene, terminal deoxynucleotidetransferase (TdT), was reported to be regulated by PP1 via Ikaros dephosphorylation [63]. Dephosphorylation of Ikaros by PP1 increases Ikaros’ DNA-binding affinity, its protein stability, and its ability to function as a transcriptional regulator [54]. The presented data using mutant Ikaros that is unable to interact with PP1 showed that PP1 is a critical regulator of Ikaros’ ability to control RAB20 transcription and that PP1 directly counteracts CK2 effects on RAB20 transcription. Thus, the presented data demonstrate the opposing effects of CK2 and PP1 on Rab20 function via control of Ikaros activity as a regulator of Rab20 expression (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Model of proposed regulation of Rab20 expression by Ikaros, CK2, and PP1α. Ikaros represses RAB20 transcription. PP1α stimulates Ikaros activity resulting in decreased RAB20 transcription. CK2 inhibits Ikaros activity resulting in increased Rab20 expression.

In summary, the results presented in this manuscript identify a novel regulatory network in leukemia that involves CK2, PP1, Ikaros and the small GTPase Rab20. The data revealed an intersection of CK2 kinase and PP1 phosphatase signaling via phosphorylation and/or dephosphorylation of the Ikaros tumor suppressor and show that CK2 and PP1 signal transduction pathways have opposing effects on the expression of the Rab20 small GTPase. The results presented here provide novel insights into signaling networks that regulate tumor suppression in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells and Cell Culture

Nalm6 and 697 B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ), respectively. Primary B-ALL leukemia cells were obtained from Loma Linda University (Loma Linda, CA, USA). These samples were taken from patients and de-identified by stripping them of all direct patient identifiers. Their use was approved by the institutional review boards at Loma Linda University and the Penn State College of Medicine. All of the cell lines and patient samples used in this study expressed wild-type IKZF1. Nalm6 and 697 cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Corning) supplemented with 0.03% L-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) (RPMI 1640–10). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 overnight. Primary leukemia cell lines were briefly cultured (1 day) in the same conditions prior to in vitro experimentation.

4.2. Metanalyses

Ikaros binding at the RAB20 promoter in patient-derived human pre-B ALL xenograft cells, LAX2, was determined by analyzing genome-wide Ikaros ChIP-seq data made previously available by H. Schjerven and M. Muschen on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under access number GSE58825 [112]. The GEO contributing authors noted that LAX2 expresses wild-type, full-length Ikaros. The correlation between IKZF1 and RAB20 expression in patients with B-ALL was determined by analyzing gene expression datasets made publicly available by ML den Boer and JM Boer on the Gene Expression Omnibus under access number GSE87070 [113].

4.3. Reagents

4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBB) (Sigma), CX-4945 (MedChem Express), calyculin A (CalBiochem), and tautomycin (EMD Millipore) were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma) to create stock solutions. Control cell lines were dosed with a volume of DMSO equivalent to the volume received by the cells treated with the highest concentration of drug.

4.4. CaPO4 Transfection and 293T Gene Expression

Lenti-X 293T cells (Clontech) were grown in DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 4.5% glucose, 0.06% L-glutamine, 0.01% sodium pyruvate, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) (DMEM–10). 293T cells were trypsinized with 1.0 mL of 0.25% trypsin (Corning) at 90% confluency and 2.0 × 106 cells were resuspended in 9.0 mL of DMEM-10, plated in a 10 cm tissue culture dish, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 overnight. For one 10 cm dish of 293T cells, 20 μg of transfection-grade pcDNA3.1 expression plasmid (prepared using the Macherey–Nagel Nucleobond Xtra Maxi kit) was diluted with 100 μL of freshly-prepared, sterile-filtered 2.0 M CaCl2 (Sigma). This mixture was then diluted to 500 μL with sterile, DNase-free water. We added 500 μL of 0.22 μm filtered 2× Hepes-buffered saline, pH 7.05, dropwise to the DNA-CaCl2 suspension with constant agitation. This suspension was incubated at room temperature for 10 min before being added dropwise to the plated Lenti-X 293T cells, which were returned to the cell culture incubator. After 24 h, the transfection media was aspirated and the cells were supplied with 10 mL of fresh DMEM-10. 293T cells were then grown for an additional 48 h before harvesting total RNA or formaldehyde crosslinking for chromatin immunoprecipitation.

4.5. Expression Plasmids

The construction of the expression plasmids used in this study were described previously: pcDNA3.1-IKZF1(WT), pcDNA3.1-IKZF1(A11), and pcDNA3.1-IKZF1(D11) in [49]; pcDNA3.1-IKZF1(465-7A) and pcDNA3.1-IKZF1(465-7A + A11) in [54]; and pMIG-CTL & pMIG-IKZF1(WT) in [114].

4.6. Luciferase Reporter Assay

The luciferase reporter assay experiment was performed as previously described [115]. The pROM-RAB20 vector was purchased from Switchgear Genomics (S719730) and incorporated the RAB20 promoter from bases –847 to +59 relative to the RAB20 transcription start site (TSS).

4.7. Retroviral Transduction

Retroviruses were produced by transient transfection in amphotropic packaging 293 cell lines as described previously [49] using pMIG-CTL or pMIG-IKZF1(WT). Nalm6 and 697 cell lines were plated in 24-well plates at 4 × 105 cells/well and suspended in retroviral supernatants with 10 μg/mL polybrene and centrifuged at 1000× g at 37 °C for 2 h. The cells were then suspended in fresh RPMI 1640–10 and cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 3 days. The GFP+ cells were then sorted using a FACS Aria SORP (Becton Dickinson) instrument in the Penn State College of Medicine’s Flow Cytometry Core. Sorted cells were further cultured using the above conditions.

4.8. Ikaros and CK2 shRNA Knockdown

Ikaros (IKZF1) and CSNK2A1 (CK2α) knockdown in Nalm6 and 697 cells was accomplished using pGP-V-RS shRNA plasmids (Origene) and a neon electroporation system (ThermoFisher Scientific) as described previously [115]. Knockdown of Ikaros and CK2α was confirmed using qRT-PCR.

4.9. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA isolation, cDNA generation, and qPCR conditions were previously described [115]. The following primers were used in this study: 18s RNA: GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT (sense) and CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG (antisense); RAB20: CGCCAAGACCGGCTACAAT (sense) and GGCACCACCAGGTCAAAGAG (antisense); CSNK2A1 (CK2α): AGCGATGGGAACGCTTTG (sense) and AAGGCCTCAGGGCTGACAA (antisense); and IKZF1: GGCGCGGTGCTCCTCCT (sense) and TCCGACACGCCCTACGACA (antisense).

4.10. qChIP

qChIP assays for Ikaros binding in B-ALL cell lines were previously described [116]. qChIP assays for H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K9ac histone markers were performed according to the same protocol as Ikaros qChIP except using 1 × 107 cells and 1–5 μg of antibody for the histone modification markers. The qChIP primers used to link immunoprecipitated DNA to the RAB20 promoter were: AGCGCCCCCATCTCTAATCT (sense) and AATGAGCGTCTGCGGAACTC (antisense).

4.11. ChIP-Seq Experiments

ChIP-seq assays for Ikaros binding in Nalm6 cells were performed as previously described [115]. Alignment of Ikaros binding peaks with the human genome was performed by the Genome Sciences Facility at the Penn State College of Medicine. ChIP-seq data are accessible on Gene Expression Omnibus using access number GSE44218.

4.12. Antibodies

The antibodies used to immunoprecipitate and detect the C terminus of Ikaros (Ikaros-CTS) have been described previously [117]. The antibodies used for chromatin immunoprecipitation for epigenetic changes were as follows: anti-rabbit IgG (ab46540, Abcam), anti-H3K4me3 (ab8580, Abcam), anti-H3K9me3 (ab8898, Abcam), and anti-H3K9ac (ab4441, Abcam).

4.13. Statistics

P-value summaries were as follows: P > 0.05 (ns); P ≤ 0.05 (*); P < 0.01 (**); P < 0.001 (***); P < 0.0001 (****). Statistics were performed in GraphPad Prism 8. A two-tailed, unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used for Figure 2G. The statistical analyses on all other panels were determined using multiple two-tailed t-tests. Statistical significance was determined using the Holm–Sidak method with α = 0.05. Each row (representing a cell line or primary cell) was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. The number of t-tests per analysis varied based on the number of cell lines or primary cells analyzed per graph. Statistical analysis was not performed on qChIP values where the signal was less than two-fold greater than the background (α-IgG) level as binding below this level was deemed biologically insignificant. This threshold is denoted by a dotted line on all graphs containing qChIP data where permitted by the range of the y axis.

Abbreviations

| B-ALL | B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| ChIP-seq | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and Sequencing |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| PDX | Patient-Derived Xenograft |

| qChIP | Quantitative Chromatin Immunoprecipitation |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TSS | Transcription Start Site |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/5/1718/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.P., C.S. and S.D.; Formal analysis, J.L.P. and S.D.; Funding acquisition, J.L.P., C.G. and S.D.; Investigation, J.L.P., C.S. and Y.D.; Methodology, C.S. and S.D.; Project administration, C.S. and S.D.; Resources, P.K.D., Y.B., J.W.S., D.D. and A.S.; Supervision, C.S., C.G. and S.D.; Validation, J.L.P., C.S. and Y.D.; Visualization, J.L.P. and S.D.; Writing—original draft, J.L.P. and S.D.; Writing—review & editing, J.L.P. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, grant numbers CA213912 (Sinisa Dovat), CA209829 (Sinisa Dovat) and CA221109 (Jonathon L Payne); the Four Diamonds Fund (Sinisa Dovat); a Hyundai Hope on Wheels Scholar Hope Grant (Sinisa Dovat); and a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Scholar Grant (Chandrika Gowda).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Georgopoulos K., Moore D.D., Derfler B. Ikaros, an early lymphoid-specific transcription factor and a putative mediator for T cell commitment. Science. 1992;258:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1439790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo K., Landau N.R., Smale S.T. LyF-1, a transcriptional regulator that interactswith a novel class of promoters for lymphocyte-specific genes. Mollecular Cellular Biology. 1991;11:5229–5243. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molnár A., Georgopoulos K. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of functionally diverse zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994;14:8292–8303. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.12.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahm K., Ernst P., Lo K., Kim G.S., Turck C., Smale S.T. The lymphoid transcription factor LyF-1 is encoded by specific, alternatively spliced mRNAs derived from the Ikaros gene. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994;14:7111–7123. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.11.7111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Georgopoulos K., Bigby M., Wang J.H., Molnar A., Wu P., Winandy S., Sharpe A. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J.H., Nichogiannopoulou A., Wu L., Sun L., Sharpe A.H., Bigby M., Georgopoulos K. Selective defects in the development of the fetal and adult lymphoid system in mice with an Ikaros null mutation. Immunity. 1996;5:537–549. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigvardsson M. Molecular Regulation of Differentiation in Early B-Lymphocyte Development. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1928. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winandy S., Wu P., Georgopoulos K. A dominant mutation in the Ikaros gene leads to rapid development of leukemia and lymphoma. Cell. 1995;83:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullighan C.G., Goorha S., Radtke I., Miller C.B., Coustan-Smith E., Dalton J.D., Girtman K., Mathew S., Ma J., Pounds S.B., et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullighan C., Downing J. Ikaros and acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:847–849. doi: 10.1080/10428190801947500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullighan C.G., Miller C.B., Radtke I., Phillips L.A., Dalton J., Ma J., White D., Hughes T.P., Le Beau M.M., Pui C.H., et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuiper R.P., Schoenmakers E.F., van Reijmersdal S.V., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., van Kessel A.G., van Leeuwen F.N., Hoogerbrugge P.M. High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia. 2007;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iacobucci I., Lonetti A., Cilloni D., Messa F., Ferrari A., Zuntini R., Ferrari S., Ottaviani E., Arruga F., Paolini S., et al. Identification of different Ikaros cDNA transcripts in Philadelphia-positive adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia by a high-throughput capillary electrophoresis sizing method. Haematologica. 2008;93:1814–1821. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iacobucci I., Storlazzi C.T., Cilloni D., Lonetti A., Ottaviani E., Soverini S., Astolfi A., Chiaretti S., Vitale A., Messa F., et al. Identification and molecular characterization of recurrent genomic deletions on 7p12 in the IKZF1 gene in a large cohort of BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients: on behalf of Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto Acute Leukemia Working Party (GIMEMA AL WP) Blood. 2009;114:2159–2167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coccaro N., Anelli L., Zagaria A., Specchia G., Albano F. Next-Generation Sequencing in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2929. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mata-Rocha M., Rangel-Lopez A., Jimenez-Hernandez E., Morales-Castillo B.A., Gonzalez-Torres C., Gaytan-Cervantes J., Alvarez-Olmos E., Nunez-Enriquez J.C., Fajardo-Gutierrez A., Martin-Trejo J.A., et al. Identification and Characterization of Novel Fusion Genes with Potential Clinical Applications in Mexican Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2394. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J., Ding L., Holmfeldt L., Wu G., Heatley S.L., Payne-Turner D., Easton J., Chen X., Wang J., Rusch M., et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman F.D., Gurel Z., Al-Zubeidi D., Fried A.J., Icardi M., Song C., Dovat S. Congenital pancytopenia and absence of B lymphocytes in a neonate with a mutation in the Ikaros gene. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:591–597. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida N., Sakaguchi H., Muramatsu H., Okuno Y., Song C., Dovat S., Shimada A., Ozeki M., Ohnishi H., Teramoto T., et al. Germline IKAROS mutation associated with primary immunodeficiency that progressed to T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31:1221–1223. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Rooij J.D., Beuling E., van den Heuvel-Eibrink M.M., Obulkasim A., Baruchel A., Trka J., Reinhardt D., Sonneveld E., Gibson B.E., Pieters R., et al. Recurrent deletions of IKZF1 in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100:1151–1159. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.124321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theocharides A.P., Dobson S.M., Laurenti E., Notta F., Voisin V., Cheng P.Y., Yuan J.S., Guidos C.J., Minden M.D., Mullighan C.G., et al. Dominant-negative Ikaros cooperates with BCR-ABL1 to induce human acute myeloid leukemia in xenografts. Leukemia. 2015;29:177–187. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unnikrishnan A., Guan Y.F., Huang Y., Beck D., Thoms J.A., Peirs S., Knezevic K., Ma S., de Walle I.V., de Jong I., et al. A quantitative proteomics approach identifies ETV6 and IKZF1 as new regulators of an ERG-driven transcriptional network. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:10644–10661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Sligte N.E., Krumbholz M., Pastorczak A., Scheijen B., Tauer J.T., Nowasz C., Sonneveld E., de Bock G.H., Meeuwsen-de Boer T.G., van Reijmersdal S., et al. DNA copy number alterations mark disease progression in paediatric chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2014;166:250–253. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosseler M., Marani V., Broukou A., Lequeux A., Kaoma T., Schlesser V., Francois J.H., Palissot V., Berchem G.J., Aouali N., et al. Inhibition of HIF1alpha-Dependent Upregulation of Phospho-l-Plastin Resensitizes Multiple Myeloma Cells to Frontline Therapy. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2018:19. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L., Howarth A., Clark R.E. Ikaros transcripts Ik6/10 and levels of full-length transcript are critical for chronic myeloid leukaemia blast crisis transformation. Leukemia. 2014;28:1745–1747. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yagi T., Hibi S., Takanashi M., Kano G., Tabata Y., Imamura T., Inaba T., Morimoto A., Todo S., Imashuku S. High frequency of Ikaros isoform 6 expression in acute myelomonocytic and monocytic leukemias: implications for up-regulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-XL in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2002;99:1350–1355. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.4.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tefferi A. Novel mutations and their functional and clinical relevance in myeloproliferative neoplasms: JAK2, MPL, TET2, ASXL1, CBL, IDH and IKZF1. Leukemia. 2010;24:1128–1138. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bavaro L., Martelli M., Cavo M., Soverini S. Mechanisms of Disease Progression and Resistance to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: An Update. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:6141. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullighan C.G., Su X., Zhang J., Radtke I., Phillips L.A., Miller C.B., Ma J., Liu W., Cheng C., Schulman B.A., et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J. Med. 2009;360:470–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harvey R.C., Mullighan C.G., Chen I.M., Wharton W., Mikhail F.M., Carroll A.J., Kang H., Liu W., Dobbin K.K., Smith M.A., et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 is associated with mutation of JAK kinases, alteration of IKZF1, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and a poor outcome in pediatric B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:5312–5321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey R.C., Mullighan C.G., Wang X., Dobbin K.K., Davidson G.S., Bedrick E.J., Chen I.M., Atlas S.R., Kang H., Ar K., et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. 2010;116:4874–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuiper R.P., Waanders E., van der Velden V.H., van Reijmersdal S.V., Venkatachalam R., Scheijen B., Sonneveld E., van Dongen J.J., Veerman A.J., van Leeuwen F.N., et al. IKZF1 deletions predict relapse in uniformly treated pediatric precursor B-ALL. Leukemia. 2010;24:1258–1264. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van der Veer A., Waanders E., Pieters R., Willemse M.E., Van Reijmersdal S.V., Russell L.J., Harrison C.J., Evans W.E., van der Velden V.H., Hoogerbrugge P.M., et al. Independent prognostic value of BCR-ABL1-like signature and IKZF1 deletion, but not high CRLF2 expression, in children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood. 2013;122:2622–2629. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-462358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marke R., Havinga J., Cloos J., Demkes M., Poelmans G., Yuniati L., van Ingen Schenau D., Sonneveld E., Waanders E., Pieters R., et al. Tumor suppressor IKZF1 mediates glucocorticoid resistance in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:1599–1603. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinelli G., Iacobucci I., Soverini S., Piccaluga P.P., Cilloni D., Pane F. New mechanisms of resistance in Philadelphia chromosome acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2009;2:297–303. doi: 10.1586/ehm.09.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinelli G., Iacobucci I., Storlazzi C.T., Vignetti M., Paoloni F., Cilloni D., Soverini S., Vitale A., Chiaretti S., Cimino G., et al. IKZF1 (Ikaros) deletions in BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are associated with short disease-free survival and high rate of cumulative incidence of relapse: a GIMEMA AL WP report. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:5202–5207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J., Sif S., Jones B., Jackson A., Koipally J., Heller E., Winandy S., Viel A., Sawyer A., Ikeda T., et al. Ikaros DNA-binding proteins direct formation of chromatin remodeling complexes in lymphocytes. Immunity. 1999;10:345–355. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koipally J., Kim J., Jones B., Jackson A., Avitahl N., Winandy S., Trevisan M., Nichogiannopoulou A., Kelley C., Georgopoulos K. Ikaros chromatin remodeling complexes in the control of differentiation of the hemo-lymphoid system. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant. Biol. 1999;64:79–86. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su R.C., Brown K.E., Saaber S., Fisher A.G., Merkenschlager M., Smale S.T. Dynamic assembly of silent chromatin during thymocyte maturation. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:502–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sridharan R., Smale S.T. Predominant interaction of both Ikaros and Helios with the NuRD complex in immature thymocytes. J. Biol Chem. 2007;282:30227–30238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koipally J., Renold A., Kim J., Georgopoulos K. Repression by Ikaros and Aiolos is mediated through histone deacetylase complexes. Embo J. 1999;18:3090–3100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgopoulos K. Haematopoietic cell-fate decisions, chromatin regulation and ikaros. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown K.E., Guest S.S., Smale S.T., Hahm K., Merkenschlager M., Fisher A.G. Association of transcriptionally silent genes with Ikaros complexes at centromeric heterochromatin. Cell. 1997;91:845–854. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J.H., Ebersole T., Kouprina N., Noskov V.N., Ohzeki J., Masumoto H., Mravinac B., Sullivan B.A., Pavlicek A., Dovat S., et al. Human gamma-satellite DNA maintains open chromatin structure and protects a transgene from epigenetic silencing. Genome Res. 2009;19:533–544. doi: 10.1101/gr.086496.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez-del Arco P., Maki K., Georgopoulos K. Phosphorylation controls Ikaros’s ability to negatively regulate the G(1)-S transition. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:2797–2807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2797-2807.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomez-del Arco P., Koipally J., Georgopoulos K. Ikaros SUMOylation: switching out of repression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:2688–2697. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2688-2697.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomes A.M., Soares M.V., Ribeiro P., Caldas J., Povoa V., Martins L.R., Melao A., Serra-Caetano A., de Sousa A.B., Lacerda J.F., et al. Adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells display decreased PTEN activity and constitutive hyperactivation of PI3K/Akt pathway despite high PTEN protein levels. Haematologica. 2014;99:1062–1068. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.096438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evangelisti C., Chiarini F., McCubrey J.A., Martelli A.M. Therapeutic Targeting of mTOR in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: An Update. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1878. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gurel Z., Ronni T., Ho S., Kuchar J., Payne K.J., Turk C.W., Dovat S. Recruitment of ikaros to pericentromeric heterochromatin is regulated by phosphorylation. J. Biol Chem. 2008;283:8291–8300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song C., Gowda C., Pan X., Ding Y., Tong Y., Tan B.H., Wang H., Muthusami S., Ge Z., Sachdev M., et al. Targeting casein kinase II restores Ikaros tumor suppressor activity and demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in high-risk leukemia. Blood. 2015;126:1813–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-651505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gowda C., Sachdev M., Muthusami S., Kapadia M., Petrovic-Dovat L., Hartman M., Ding Y., Song C., Payne J.L., Tan B.H., et al. Casein Kinase II (CK2) as a Therapeutic Target for Hematological Malignancies. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:95–107. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161006154311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gowda C., Soliman M., Kapadia M., Ding Y., Payne K., Dovat S. Casein Kinase II (CK2), Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 (GSK-3) and Ikaros mediated regulation of leukemia. Adv. Biol Regul. 2017;65:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gowda C., Song C., Kapadia M., Payne J.L., Hu T., Ding Y., Dovat S. Regulation of cellular proliferation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia by Casein Kinase II (CK2) and Ikaros. Adv. Biol Regul. 2017;63:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Popescu M., Gurel Z., Ronni T., Song C., Hung K.Y., Payne K.J., Dovat S. Ikaros stability and pericentromeric localization are regulated by protein phosphatase 1. J. Biol Chem. 2009;284:13869–13880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900209200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mumby M.C., Walter G. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases: structure, regulation, and functions in cell growth. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:673–699. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao S., Lee E.Y. Targeting of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase-1 to the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8318–8324. doi: 10.1021/bi962814r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Armstrong C.G., Doherty M.J., Cohen P.T. Identification of the separate domains in the hepatic glycogen-targeting subunit of protein phosphatase 1 that interact with phosphorylase a, glycogen and protein phosphatase 1. (Pt 3)Biochem J. 1998;336:699–704. doi: 10.1042/bj3360699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen P.T. Protein phosphatase 1--targeted in many directions. (Pt 2)J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:241–256. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ceulemans H., Bollen M. Functional diversity of protein phosphatase-1, a cellular economizer and reset button. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1–39. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X., Liu B., Li N., Li H., Qiu J., Zhang Y., Cao X. IPP5, a novel protein inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1, promotes G1/S progression in a Thr-40-dependent manner. J. Biol Chem. 2008;283:12076–12084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferreira M., Beullens M., Bollen M., Van Eynde A. Functions and therapeutic potential of protein phosphatase 1: Insights from mouse genetics. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019;1866:16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gil R.S., Vagnarelli P. Protein phosphatases in chromatin structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019;1866:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang H., Song C., Gurel Z., Song N., Ma J., Ouyang H., Lai L., Payne K.J., Dovat S. Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) and Casein Kinase II (CK2) regulate Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in thymocytes and T-cell leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:2230–2235. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song C., Li Z., Erbe A.K., Savic A., Dovat S. Regulation of Ikaros function by casein kinase 2 and protein phosphatase 1. World J. Biol Chem. 2011;2:126–131. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v2.i6.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dovat S., Song C., Payne K.J., Li Z. Ikaros, CK2 kinase, and the road to leukemia. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2011;356:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0964-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ge Z., Gu Y., Xiao L., Han Q., Li J., Chen B., Yu J., Kawasawa Y.I., Payne K.J., Dovat S., et al. Co-existence of IL7R high and SH2B3 low expression distinguishes a novel high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia with Ikaros dysfunction. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46014–46027. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ge Z., Gu Y., Zhao G., Li J., Chen B., Han Q., Guo X., Liu J., Li H., Yu M.D., et al. High CRLF2 expression associates with IKZF1 dysfunction in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia without CRLF2 rearrangement. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49722–49732. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ge Z., Guo X., Li J., Hartman M., Kawasawa Y.I., Dovat S., Song C. Clinical significance of high c-MYC and low MYCBP2 expression and their association with Ikaros dysfunction in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42300–42311. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ge Z., Han Q., Gu Y., Ge Q., Ma J., Sloane J., Gao G., Payne K.J., Szekely L., Song C., et al. Aberrant ARID5B expression and its association with Ikaros dysfunction in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogenesis. 2018;7:84. doi: 10.1038/s41389-018-0095-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ge Z., Li M., Zhao G., Xiao L., Gu Y., Zhou X., Yu M.D., Li J., Dovat S., Song C. Novel dynamin 2 mutations in adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:2746–2751. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ge Z., Song E.J., Kawasawa Y.I., Li J., Dovat S., Song C. WDR5 high expression and its effect on tumorigenesis in leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37740–37754. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ge Z., Zhou X., Gu Y., Han Q., Li J., Chen B., Ge Q., Dovat E., Payne J.L., Sun T., et al. Ikaros regulation of the BCL6/BACH2 axis and its clinical relevance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2017;8:8022–8034. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dovat S. Ikaros in hematopoiesis and leukemia. World J. Biol Chem. 2011;2:105–107. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v2.i6.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang H., Ouyang H., Lai L., Petrovic-Dovat L., Stankov K., Bogdanovic G., Dovat S. Pathogenesis and regulation of cellular proliferation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia—the role of Ikaros. J. BUON. 2014;19:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ronni T., Payne K.J., Ho S., Bradley M.N., Dorsam G., Dovat S. Human Ikaros function in activated T cells is regulated by coordinated expression of its largest isoforms. J. Biol Chem. 2007;282:2538–2547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Payne K.J., Dovat S. Ikaros and tumor suppression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Crit Rev. Oncog. 2011;16:3–12. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.v16.i1-2.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ding Y., Zhang B., Payne J.L., Song C., Ge Z., Gowda C., Iyer S., Dhanyamraju P.K., Dorsam G., Reeves M.E., et al. Ikaros tumor suppressor function includes induction of active enhancers and super-enhancers along with pioneering activity. Leukemia. 2019;33:2720–2731. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0474-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Han Q., Ma J., Gu Y., Song H., Kapadia M., Kawasawa Y.I., Dovat S., Song C., Ge Z. RAG1 high expression associated with IKZF1 dysfunction in adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Cancer. 2019;10:3842–3850. doi: 10.7150/jca.33989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Habermann J.K., Brucker C.A., Freitag-Wolf S., Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Kruger S., Barenboim L., Downing T., Bruch H.P., Auer G., Roblick U.J., et al. Genomic instability and oncogene amplifications in colorectal adenomas predict recurrence and synchronous carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2011;24:542–555. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Simoneau E., Chicoine J., Negi S., Salman A., Lazaris A., Hassanain M., Beauchemin N., Petrillo S., Valenti D., Amre R., et al. Next generation sequencing of progressive colorectal liver metastases after portal vein embolization. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2017;34:351–361. doi: 10.1007/s10585-017-9855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Javierre B.M., Rodriguez-Ubreva J., Al-Shahrour F., Corominas M., Grana O., Ciudad L., Agirre X., Pisano D.G., Valencia A., Roman-Gomez J., et al. Long-range epigenetic silencing associates with deregulation of Ikaros targets in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011;9:1139–1151. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pellagatti A., Esoof N., Watkins F., Langford C.F., Vetrie D., Campbell L.J., Fidler C., Cavenagh J.D., Eagleton H., Gordon P., et al. Gene expression profiling in the myelodysplastic syndromes using cDNA microarray technology. Br. J. Haematol. 2004;125:576–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Crescenzi B., La Starza R., Romoli S., Beacci D., Matteucci C., Barba G., Aventin A., Marynen P., Ciolli S., Nozzoli C., et al. Submicroscopic deletions in 5q- associated malignancies. Haematologica. 2004;89:281–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kakinuma S., Kodama Y., Amasaki Y., Yi S., Tokairin Y., Arai M., Nishimura M., Monobe M., Kojima S., Shimada Y. Ikaros is a mutational target for lymphomagenesis in Mlh1-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2007;26:2945–2949. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liang Y., Lin S., Zou L., Zhou H., Zhang J., Su B., Wan Y. Expression profiling of Rab GTPases reveals the involvement of Rab20 and Rab32 in acute brain inflammation in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2012;527:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pei G., Bronietzki M., Gutierrez M.G. Immune regulation of Rab proteins expression and intracellular transport. J. Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:41–50. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Torri A., Beretta O., Ranghetti A., Granucci F., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Foti M. Gene expression profiles identify inflammatory signatures in dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9404. doi: 10.1371/annotation/53736770-ad30-4c6b-8279-d344a1232cc6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pei G., Schnettger L., Bronietzki M., Repnik U., Griffiths G., Gutierrez M.G. Interferon-gamma-inducible Rab20 regulates endosomal morphology and EGFR degradation in macrophages. Mol. Biol Cell. 2015;26:3061–3070. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gutierrez M.G., Mishra B.B., Jordao L., Elliott E., Anes E., Griffiths G. NF-kappa B activation controls phagolysosome fusion-mediated killing of mycobacteria by macrophages. J. Immunol. 2008;181:2651–2663. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cho S.J., Huh J.E., Song J., Rhee D.K., Pyo S. Ikaros negatively regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in macrophages: involvement of Ikaros phosphorylation by casein kinase 2. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:3290–3303. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dumortier A., Kirstetter P., Kastner P., Chan S. Ikaros regulates neutrophil differentiation. Blood. 2003;101:2219–2226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nakayama H., Ishimaru F., Katayama Y., Nakase K., Sezaki N., Takenaka K., Shinagawa K., Ikeda K., Niiya K., Harada M. Ikaros expression in human hematopoietic lineages. Exp. Hematol. 2000;28:1232–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Winandy S., Wu L., Wang J.H., Georgopoulos K. Pre-T cell receptor (TCR) and TCR-controlled checkpoints in T cell differentiation are set by Ikaros. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1039–1048. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Amillet J.M., Ferbus D., Real F.X., Antony C., Muleris M., Gress T.M., Goubin G. Characterization of human Rab20 overexpressed in exocrine pancreatic carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2006;37:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Turner N., Lambros M.B., Horlings H.M., Pearson A., Sharpe R., Natrajan R., Geyer F.C., van Kouwenhove M., Kreike B., Mackay A., et al. Integrative molecular profiling of triple negative breast cancers identifies amplicon drivers and potential therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2010;29:2013–2023. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ho J.R., Chapeaublanc E., Kirkwood L., Nicolle R., Benhamou S., Lebret T., Allory Y., Southgate J., Radvanyi F., Goud B. Deregulation of Rab and Rab effector genes in bladder cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Song C., Pan X., Ge Z., Gowda C., Ding Y., Li H., Li Z., Yochum G., Muschen M., Li Q., et al. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression by Ikaros, HDAC1 and Casein Kinase II in leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:1436–1440. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stenmark H., Olkkonen V.M. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol. 2001:2. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-5-reviews3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fukuda M. Regulation of secretory vesicle traffic by Rab small GTPases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2801–2813. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zerial M., McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gutierrez M.G. Functional role(s) of phagosomal Rab GTPases. Small GTPases. 2013;4:148–158. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.25604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pei G., Repnik U., Griffiths G., Gutierrez M.G. Identification of an immune-regulated phagosomal Rab cascade in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:2071–2082. doi: 10.1242/jcs.144923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sung M.H., Li N., Lao Q., Gottschalk R.A., Hager G.L., Fraser I.D. Switching of the relative dominance between feedback mechanisms in lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB signaling. Sci Signal. 2014:7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Oh K.S., Gottschalk R.A., Lounsbury N.W., Sun J., Dorrington M.G., Baek S., Sun G., Wang Z., Krauss K.S., Milner J.D., et al. Dual Roles for Ikaros in Regulation of Macrophage Chromatin State and Inflammatory Gene Expression. J. Immunol. 2018;201:757–771. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Navasa N., Martin-Ruiz I., Atondo E., Sutherland J.D., Angel Pascual-Itoiz M., Carreras-Gonzalez A., Izadi H., Tomas-Cortazar J., Ayaz F., Martin-Martin N., et al. Ikaros mediates the DNA methylation-independent silencing of MCJ/DNAJC15 gene expression in macrophages. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14692. doi: 10.1038/srep14692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dovat S., Ronni T., Russell D., Ferrini R., Cobb B.S., Smale S.T. A common mechanism for mitotic inactivation of C2H2 zinc finger DNA-binding domains. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2985–2990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1040502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li Z., Song C., Ouyang H., Lai L., Payne K.J., Dovat S. Cell cycle-specific function of Ikaros in human leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:69–76. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ge Z., Gu Y., Han Q., Sloane J., Ge Q., Gao G., Ma J., Song H., Hu J., Chen B., et al. Plant homeodomain finger protein 2 as a novel IKAROS target in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Epigenomics. 2018;10:59–69. doi: 10.2217/epi-2017-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ge Z., Gu Y., Han Q., Zhao G., Li M., Li J., Chen B., Sun T., Dovat S., Gale R.P., et al. Targeting High Dynamin-2 (DNM2) Expression by Restoring Ikaros Function in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38004. doi: 10.1038/srep38004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gowda C.S., Song C., Ding Y., Kapadia M., Dovat S. Protein signaling and regulation of gene transcription in leukemia: role of the Casein Kinase II-Ikaros axis. J. Investig Med. 2016;64:735–739. doi: 10.1136/jim-2016-000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schjerven H., Ayongaba E.F., Aghajanirefah A., McLaughlin J., Cheng D., Geng H., Boyd J.R., Eggesbo L.M., Lindeman I., Heath J.L., et al. Genetic analysis of Ikaros target genes and tumor suppressor function in BCR-ABL1(+) pre-B ALL. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:793–814. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Polak R., Bierings M.B., van der Leije C.S., Sanders M.A., Roovers O., Marchante J.R.M., Boer J.M., Cornelissen J.J., Pieters R., den Boer M.L., et al. Autophagy inhibition as a potential future targeted therapy for ETV6-RUNX1-driven B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104:738–748. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.193631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cobb B.S., Morales-Alcelay S., Kleiger G., Brown K.E., Fisher A.G., Smale S.T. Targeting of Ikaros to pericentromeric heterochromatin by direct DNA binding. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2146–2160. doi: 10.1101/gad.816400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang H., Song C., Ding Y., Pan X., Ge Z., Tan B.H., Gowda C., Sachdev M., Muthusami S., Ouyang H., et al. Transcriptional Regulation of JARID1B/KDM5B Histone Demethylase by Ikaros, Histone Deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), and Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) in B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Biol Chem. 2016;291:4004–4018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.679332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fujiwara T., O’Geen H., Keles S., Blahnik K., Linnemann A.K., Kang Y.A., Choi K., Farnham P.J., Bresnick E.H. Discovering hematopoietic mechanisms through genome-wide analysis of GATA factor chromatin occupancy. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:667–681. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hahm K., Cobb B.S., McCarty A.S., Brown K.E., Klug C.A., Lee R., Akashi K., Weissman I.L., Fisher A.G., Smale S.T. Helios, a T cell-restricted Ikaros family member that quantitatively associates with Ikaros at centromeric heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 1998;12:782–796. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.