Abstract

Background & Aims:

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a clinical syndrome defined by liver failure on preexisting chronic liver disease and is often associated with bacterial infection with high short-term mortality. Experimental models that fully reproduce ACLF and effective pharmacological therapies are lacking.

Methods:

To mimic ACLF conditions, we developed a severe liver injury model by combining chronic injury (chronic carbon tetrachloride [CCl4] injection), acute hepatic insult (injection of a double dose CCl4), and bacterial infection (intraperitoneal injection of bacteria). Serum and liver samples from patients with ACLF or acute drug-induced liver injury (DILI) were used. Liver injury and regeneration were assessed to ascertain for potential benefits of interleukin-22 (IL-22Fc) administration.

Results:

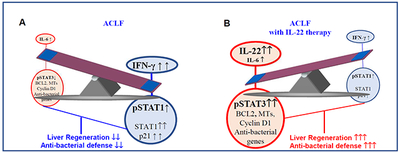

This severe liver injury model developed acute-on-chronic liver injury, bacterial infection, multi-organ injury, and high mortality, recapitulating some features of clinical ACLF. Liver regeneration in this model was severely impaired due to the shift from the activation of pro-regenerative IL-6/STAT3 to anti-regenerative IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway. The impaired IL-6/STAT3 activation was due to Kupffer cell inability to produce IL-6; whereas the enhanced STAT1 activation was due to strong innate immune response and subsequent production of IFN-γ. Compared to DILI patients, ACLF patients had higher levels of IFN-γ but lower liver regeneration. IL-22Fc treatment improved survival of the ACLF mice by reversing the STAT1/STAT3 pathway imbalance and enhancing expression of many anti-bacterial genes in a manner involving the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2.

Conclusions:

Acute-on-chronic liver injury or bacterial infection is associated with impaired liver regeneration due to a shift from the pro-regenerative to anti-regenerative pathways, IL-22Fc therapy reverses this shift and attenuates bacterial infection, thus IL-22Fc may have therapeutic potential for ACLF treatment.

Keywords: ACLF, bacteria, STAT1, STAT3, IL-6, IFN-γ

Graphical Abstract

Lay Summary:

Combination of chronic liver injury, acute hepatic insult, and bacterial infection induce severe liver injury with renal injury and high mortality, recapitulating some features of clinical acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Both fibrosis and bacterial infection contribute to impaired liver regeneration in ACLF. IL-22Fc therapy improves ACLF by reprograming of impaired regenerative pathway and attenuating bacterial infection.

Introduction

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is generally accepted as a clinical syndrome characterized by an acute hepatic insult and rapid deterioration of liver function in patients with pre-existing chronic liver disease in combination with multi-organ failure with high short-term mortality.1–5 The main etiologies of the pre-existing chronic liver disease are alcoholism and chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, while the most frequently documented acute insults that induce acute injury in ACLF include excessive alcohol drinking, HBV activation, drug-induced liver injury (DILI) etc.1–6 Bacterial infections were detected in up to 2/3 ACLF patients and contributed to the poor outcome of ACLF.7–9 Although the poor outcome is closely associated with bacterial infection,7, 8 whether bacterial infection is a consequence of ACLF or a trigger as an acute insult to induce ACLF is still a question of debate.7–9 Collectively, the outcome of ACLF likely depends on two major aspects: the recovery of multi-organ injury and the control of bacterial infection.

Despite several experimental ACLF models being reported,10–14 none of them simulates the whole pathological process of this disease. Several existing ACLF models have been developed via the combination of chronic and acute liver injury.10–14 Chronic injury is most commonly induced by injection of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) or via bile duct ligation surgery; whereas acute injury is induced by injection of D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide (LPS).10–14 Although these models include chronic and acute liver injury resulting in considerable mortality, the mean survival period is very short after the acute insult, which renders its application for preclinical interventional studies. In addition, in these models no viable bacterial infection is present while LPS injection does not fully mimic bacterial infection. In the current study, we developed a mouse model of ACLF by chronically administrating CCl4 (chronic injury) and followed by an acute injection of a higher dose of CCl4 (acute injury) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (K.P.) or cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) (bacterial infection). This model recapitulates the three major stages (chronic and acute liver injury and bacterial infection) of ACLF with an appropriate survival period for subsequent studies. Furthermore, we studied liver regeneration and explored the therapeutic potential of interleukin-22Fc (IL-22Fc) in this model. IL-22Fc is a recombinant fusion protein consisting of two human IL-22 molecules linked to an immunoglobulin constant region (IgG2-Fc) with an extended half-life, and is currently being examined in clinical trials for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis.15

The liver has a great ability to regenerate after loss of tissue or injury, which is controlled by several signaling pathways that are activated by a variety of cytokines and growth factors.16 Among these pathways, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), mainly activated by IL-6 and IL-22, is a major pathway that promotes liver regeneration;16 whereas STAT1, mainly activated by IFN-γ, is a potent inhibitory pathway that blocks liver regeneration.17 The balance of STAT3 and STAT1 activation plays a key role in controlling liver injury and regeneration.18 In the current study, we found the disruption of STAT3 and STAT1 balance in the liver of ACLF mice, causing the impairment of liver regeneration. Treatment with IL-22Fc induced predominant STAT3 activation but inhibited STAT1 activation in the liver of ACLF mice, thereby ameliorating ACLF. IL-22 is produced by immune cells but does not target these cells, instead IL-22 mainly targets epithelial cells due to the restricted expression of IL-22R1 on epithelial cells including hepatocytes.15 IL-22 was initially identified as a hepatoprotective cytokine and was subsequently demonstrated to protect against epithelial cell injury in multiple organs.15 In addition, IL-22 also protects against bacterial infection by stimulating epithelial cells to produce a large number of anti-bacterial proteins.19 A recent study reported that serum IL-22 and IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) were elevated and correlated with disease severity and mortality in ACLF patients,20 but it is not clear whether this elevated IL-22/IL-22BP contributed to ACLF or played a compensative role in protecting against ACLF. Thus, it is important to conduct a pre-clinical study to examine the therapeutic potential of IL-22Fc treatment in our newly established ACLF model. Our results revealed that IL-22Fc not only promoted liver repair but also suppressed bacterial infection. The molecular mechanisms underlying these beneficial functions of IL-22Fc were also investigated in this model and in ACLF patients.

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

Male C57BL/6J mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with CCl4 (0.2 ml/kg, twice a week) for 8 weeks, subsequent injection of a double dose of CCl4 (0.4 ml/kg), followed by i.p. injection with Klebsiella pneumonia (K.P.) strain 43816 (ATCC, Manassas, VA),21 or cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) surgery, as detailed in Supplementary document. Mice were also intravenously treated with IL-22-Fc (0.5 μg/g) (kindly provided by Generon, Shanghai, China)22 or its isotype IgG2 control (0.5 μg/g) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Male hepatocyte-specific Bcl2 transgenic mice (Bcl2Hep-TG) and their littermate controls on a C57BL/6J background were generated as described in Supplementary materials. Mice were housed in polycarbonate cages (4 mice per cage) and maintained in a temperature and light controlled facility (12h:12h light-dark cycle) under standard foold and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the NIAAA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Human samples

Serum samples from ACLF patients (n=40: 20 patients survived, and 20 patients died later) and DILI patients (n=20: 11 acute, 9 recovery), formalin-fixed liver tissues from ACLF patients (n=5) who were subjected to liver transplantation, and DILI patients who underwent liver biopsy for the diagnoses were obtained from the Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The characteristics of these patients are described in the Supplementary Material (Fig. S1, Table S1–6). The protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital, and written informed consents were obtained from the subjects. The explanted liver tissues from alcoholic ACLF patients (n=5) were provided by the Resources for Alcoholic Hepatitis Investigators (1R24AA025017) of the Johns Hopkins University.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± SEM and were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA). To compare values obtained from three or more groups, one-way ANOVA was used, followed by Tukey post-hoc test. The Student t test was performed to compare values obtained from two groups with two-tailed. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for non-parametric variables. Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used for survival comparison. P values calculated and the significance set at of <0.05.

Other methods are described in Supplementary document.

Results

Combinations of chronic, acute liver injury, and bacterial infection to induce ACLF in mice

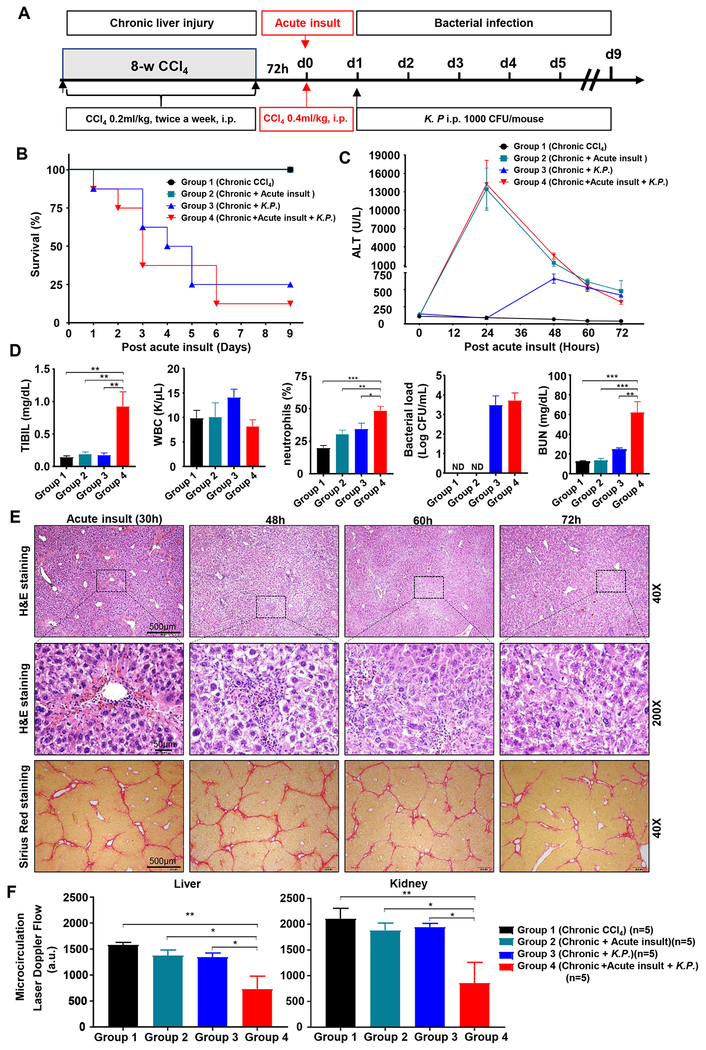

To develop a mouse model of ACLF, we performed the below combination of treatments: 8-week chronic CCl4, an acute injection of a double dose of CCl4 and K.P. bacteria (the reasons for selecting these doses are described in Fig. S2). As illustrated in Fig. 1A–E, chronic CCl4-treated mice were divided into four groups. Among these four groups, the group 4 mice (chronic + acute CCl4 + bacterial infection) had the closest features to ACLF, showing high short-term mortality within 7 days (87.5%), high levels of serum ALT and bilirubin, elevation of circulating neutrophils and viable bacteria load in blood, and severe pathological liver damage including necrosis, inflammation (Fig. 1E) and strong TUNEL staining positivity (Fig. S3A). We also tested this model with longer (16-week) CCl4 treatment and found similar fibrosis and short-term mortality between 8-week and 16-week CCl4 ACLF groups as demonstrated by Sirius staining and quantitating the collagen proportionate area (CPA) and measuring survival rate (Fig. S3B–D).

Figure 1. Characterization of a mouse model of ACLF.

(A) Schematic timeline of the procedures. C57BL/6J mice were treated with 8-week CCl4 to induce chronic liver injury, followed by additional challenges: Group 1, no additional challenges; Group 2, acute insult (a double dose of CCl4 injection); Group 3, Klebsiella pneumoniae (K.P.) infection; Group 4, acute insult and K.P. infection. (B) Survival rates (n=8). (C) Serum ALT levels. (D) Total bilirubin (TBIL), white blood cells, neutrophil percentage, blood bacterial loads, and BUN were measured 72 hours post-acute CCl4 injection. (E) Representative staining images from the group 4. (F) Hepatic and renal blood flow were determined 72 hours post-acute insult. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n=4-8 in panels C-E).

The group 4 mice also had significant extrahepatic organ injury such as kidney injury, a typical characteristic of ACLF,1–6 as demonstrated by elevation of blood urea nitrogen (Fig. 1D) and severe tissue injury (Fig. S4A), reduction of renal microvascular flow (Fig. 1F, Fig. S4B), and marked elevation of lipocalin 2 (a marker for kidney injury) (Fig. S4C). Severe pathological injury included histological signs of vacuolization, brush border loss, and tubular epithelial cell detachment as demonstrated on the PAS and H&E staining. This was also partially present in the fibrosis+CCl4 group without bacterial infection, but to a much lesser extent (Fig. S4A). Finally, the group 4 mice had reduced body temperature (Fig. S4D). The reason why the renal failure only occurs in the group 4 is not clear. We can speculate that acute-on-chronic liver injury strongly impaired anti-bacterial immunity and subsequently enhanced bacterial infection and inflammatory responses in these ACLF mice, thereby causing kidney injury.

We also performed cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) surgery to induce multi-bacterial infections to replace K.P. injection in our ACLF model and found that CLP caused similar pathological process and mortality like K.P. injection as described above (Fig. S5). However, in CLP model, it is hard to accurately control the spillage amount of cecal contents into the peritoneal cavity, and the surgical procedure significantly influences on the outcome of the model. In contrast, a single K.P. injection is easy to handle and the dose of K.P. can be controlled precisely.21 Therefore, we chose a single K.P. injection to introduce bacterial infection in the rest of this study.

Chronic liver fibrosis and/or bacterial infection inhibit acute injury-induced liver regeneration in ACLF mice

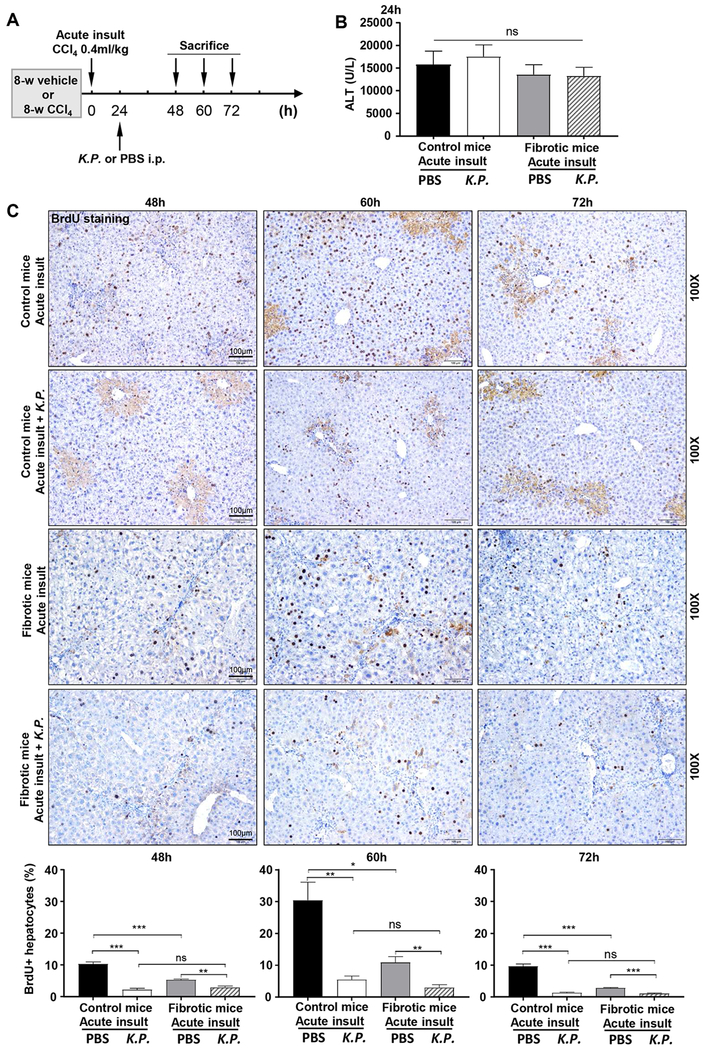

To investigate whether liver regeneration is affected in ACLF, we examined the effects of acute CCl4 on liver regeneration in control or fibrotic mice with or without K.P. infection by measuring BrdU incorporation (Fig. 2A). Acute CCl4 administration induced similar serum ALT elevation in these mice (Fig. 2B). As expected, acute CCl4 induced significantly increased liver regeneration in control mice with peak effects occurring 60 hours post CCl4 injection as demonstrated by elevation of BrdU+ hepatocytes, which was markedly suppressed by fibrosis (chronic CCl4), bacterial (K.P.) infection, or the application of both (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Liver regeneration is inhibited in ACLF mice.

(A) Schematic timeline of CCl4 and K.P. injection in C57BL/6J mice (the group 4 in Figure 1). (B) Serum ALT levels 24 hours post-acute insult (n=5). (C) BrdU was injected 2 hours before sacrifice. Representative BrdU immunostaining images are shown. The percentage of BrdU+ hepatocytes was calculated. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n=5-8 in each group).

Chronic liver fibrosis (without bacterial infection) attenuates acute injury-induced liver regeneration by attenuating the pro-regenerative IL-6/STAT3 but enhancing the anti-regenerative IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway

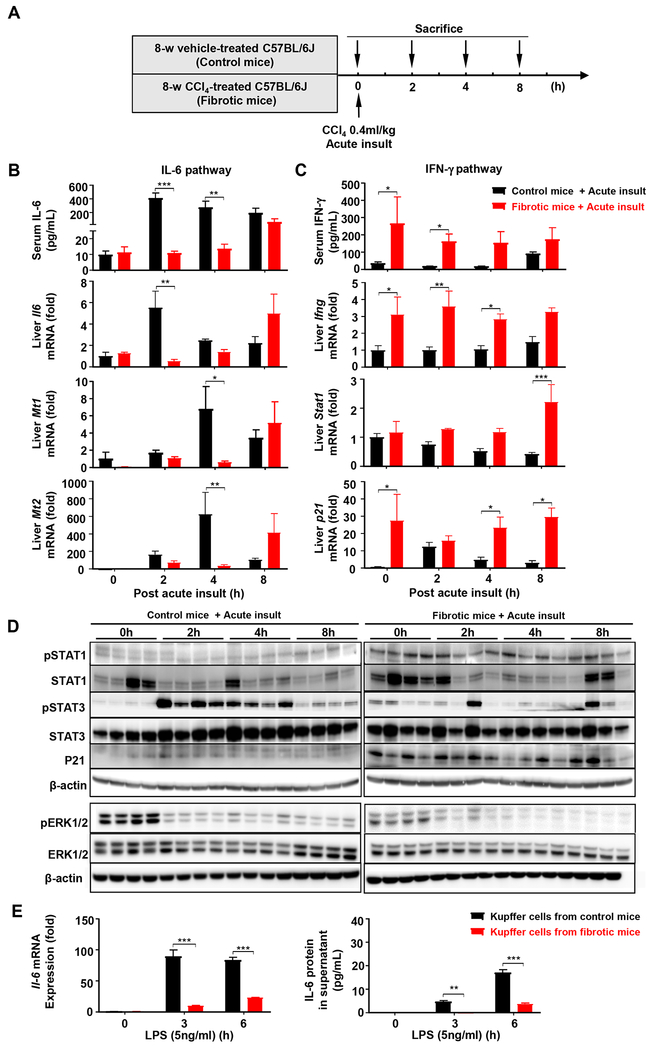

To investigate the mechanisms underlying impaired liver regeneration in fibrotic livers post-acute injury, we measured serum cytokines and found that in control mice, acute liver injury markedly elevated serum IL-6 levels but such elevation was completely blunted in fibrotic livers (Fig. 3A–B, Fig. S6A–B). Serum IFN-γ levels were slightly elevated in control mice after acute liver injury; whereas fibrotic mice had markedly higher basal IFN-γ levels (Fig. 3C). In consistence with alterations of these cytokines, the mRNA expressions of Il6 and its downstream gene metallothionein 1/2 (Mt1/2) in the fibrotic liver were suppressed while the mRNA expressions of Ifng, Stat1 and p21 genes of the IFN-γ pathway were enhanced (Fig. 3B–C). Hepatic expressions of Tnfa, Il10, and Tgfb were also higher in fibrotic versus control livers (Fig. S6C). Western blot analyses revealed that acute liver injury-mediated STAT3 activation (increased pSTAT3) were suppressed while the STAT1 pathway (as demonstrated by elevation of pSTAT1 and p21 proteins) were enhanced in fibrotic versus control mice (Fig. 3D, Fig. S6D). In contrast to STAT activation, ERK1/2 activation was suppressed after acute insult in both control and fibrotic mice with higher basal levels in control versus fibrotic mice (Fig. 3D, Fig. S6D). Interestingly, although hepatic and serum IL6 in the fibrotic mice were elevated at later time point (8 hours post-acute insult) (Fig. 3B), pSTAT3 activation was low in these mice (Fig. 3D). The reason for this disassociation is not clear and may be partially due to higher basal levels of Socs3 (a major inhibitor for pSTAT3) in the fibrotic livers (Fig. S6E).

Figure 3. The IL-6/STAT3 pathway is attenuated while the IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway is enhanced in fibrotic livers post-acute injury.

(A) Schematic timeline of the fibrotic and control mice with a double dose of CCl4 (0.4 ml/kg) (without K.P infection). (B, C) Serum IL-6 and IFN-γ, and relative mRNA expressions of Il-6 and Ifng, and their downstream target genes in the liver were determined. (D) Western blot analyses of IL-6 and IFN-γ downstream signaling pathways. (E) Kupffer cells were isolated from control and fibrotic livers and stimulated with LPS. The IL-6 mRNA and protein (in the supernatant) were measured. Student’s t-test was used for statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n= 3-5 in panel B-E).

Acute liver injury is known to elevate portal LPS, which stimulates Kupffer cells to produce IL-6 and subsequently promotes liver regeneration.16 Here we show that isolated Kupffer cells from the fibrotic livers poorly responded to LPS stimulation in vitro to express IL-6 mRNA and protein compared to those from control mice (Fig. 3E), suggesting that the reduced IL-6 levels in the fibrotic mice after acute CCl4 were due to the impaired IL-6 production by Kupffer cells.

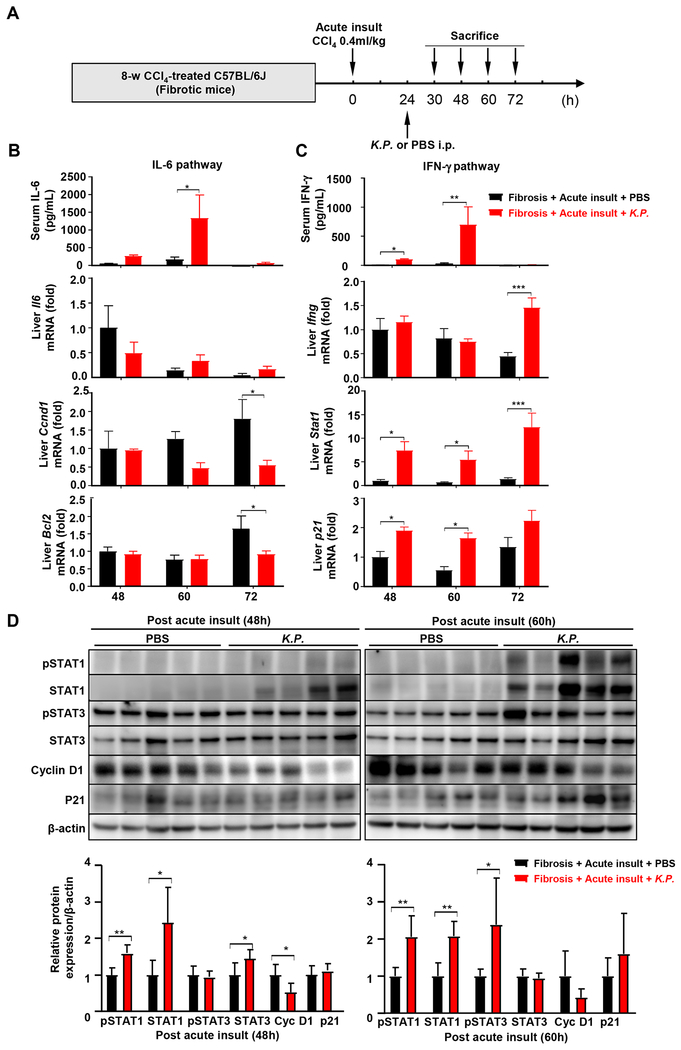

Bacterial infection suppresses acute injury-induced liver regeneration by enhancing the IFN-γ/STAT1 activation

To investigate the effects of bacterial infection on liver regeneration, we measured the serum cytokine profile. Because bacterial infection took time, we collected serum and liver samples at the late time points (48 and 60 hours) post-acute liver injury. As illustrated in Fig. 4A–C and Fig. S7, serum IFN-γ levels in the fibrotic mice with K.P. infection were approximately 8-fold higher than those without K.P. infection. Consistent with these findings, the mRNA expression of Stat1 and p21, the downstream of the IFN-γ pathway, were higher, while Ccnd1 and Bcl2 in the STAT3 pathway were inhibited in mice with bacterial infection. Furthermore, the protein expression of total/pSTAT1 was higher while the expression of cyclin D1 was lower in mice with bacterial infection compared to those without bacterial infection (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, p21, a downstream of STAT1, was not upregulated, which doesn’t seem to correlate with STAT1 upregulation. This may be because it needs time for pSTAT1 induction of p21 mRNA and then p21 protein expression.

Figure 4. The IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway is strongly activated in fibrotic livers post bacterial infection.

(A) Schematic timeline of CCl4 and K.P. injection. (B, C) Serum IL-6 and IFN-γ, and relative mRNA expressions of Il-6 and Ifng, and their downstream target genes in the liver were determined. (D) Liver extracts were subjected to western blot analysis. Relative protein expression was quantitated. Student’s t-test was used for statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n=5 in each group).

Evidence for impaired liver regeneration in ACLF patients due to the dysregulation of IL-6 and IFN-γ

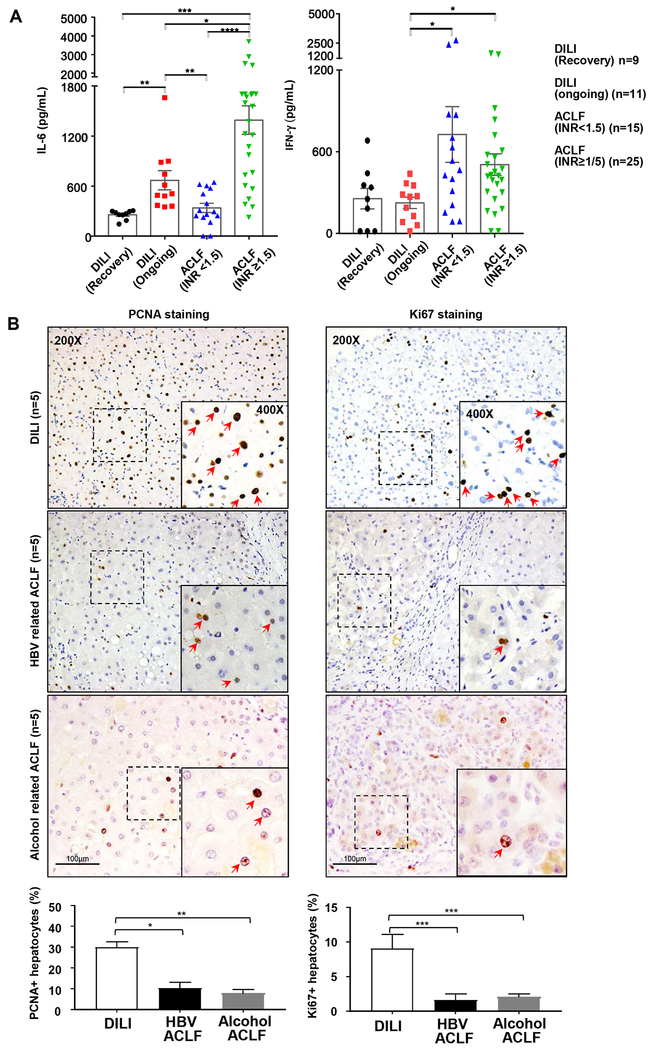

Next we measured serum IL-6 and IFN-γ in two different groups of ACLF patients: one group with prothrombin time, the international normalized ratio (INR)<1.5, which represents the early stage of ACLF, and another group INR≥1.5, which represents the later/end stages. We also choose the patients with ongoing DILI (ALT: 416.00±111.8 IU/L) as positive controls for liver regeneration, and some patients recovered from DILI (ALT: 54.00±5.96 IU/L) as negative controls. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, serum IL-6 levels were higher in the ongoing versus the recovered DILI or INR<1.5 ACLF; whereas the INR≥1.5 ACLF had highest serum IL-6 levels among these groups. Serum IFN-γ levels were elevated in both ACLF groups versus DILI groups, suggesting that the anti-regenerative cytokine IFN-γ is strongly activated in ACLF.

Figure 5. Serum IL-6 and IFN-γ levels, and liver regeneration in DILI and ACLF patients.

(A) Serum IL-6 and IFN-γ in DILI and ACLF patients (INR<1.5 or ≥1.5). (B) Immunohistochemistry staining of cell proliferating biomarker PCNA or Ki67 in DILI, HBV-ACLF and alcohol-ACLF patients. The percentage of PCNA+ or Ki67+ hepatocytes was calculated by randomly counting 10 images (10x) per sample. Kruskal-Wallis test for non-parametric variables was used for panel A, and one-way ANOVA was used for pane B statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

We next examined liver regeneration by performing Ki67 and PCNA staining in patients with end-stage of HBV-related-ACLF or alcohol-related-ACLF from the explanted samples. We also chose 5 biopsied liver samples from DILI patients who had ongoing liver injury as positive controls for liver regeneration. As illustrated in Fig. 5B, a great number of PCNA+ and Ki67+ hepatocytes were detected in ongoing DILI; whereas HBV-ACLF or alcohol-ACLF had a much lower number of PCNA+ and Ki67+ hepatocytes in their explanted livers.

IL-22Fc protein therapy improves liver regeneration and survival in ACLF mice by reprograming of the regenerative pathway

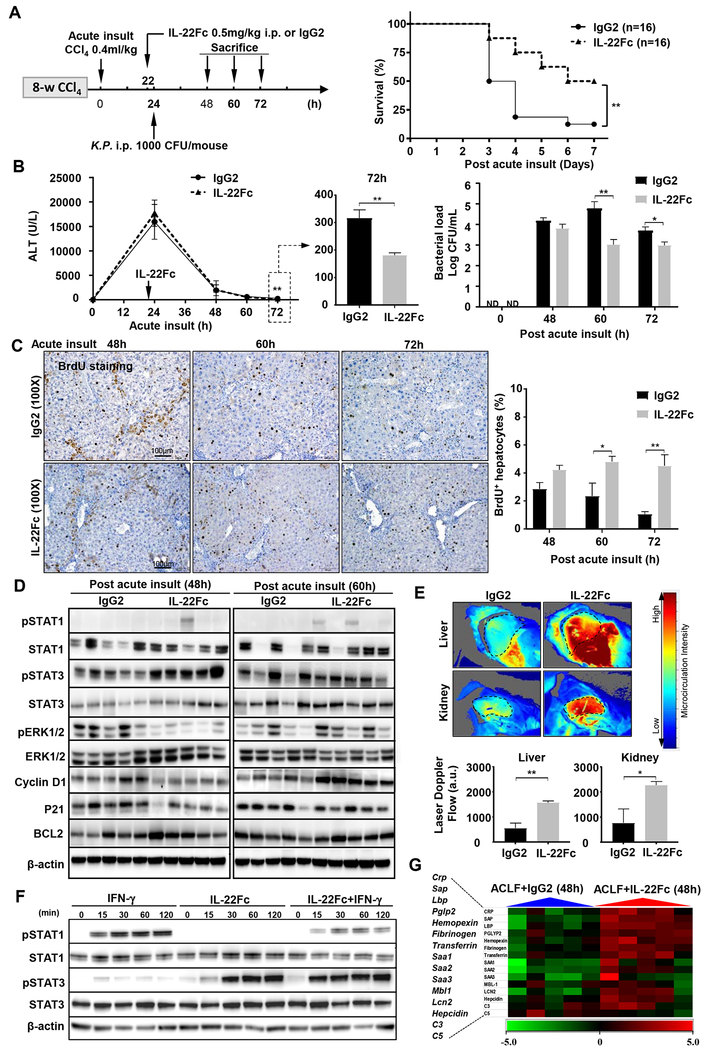

IL-22 is well-known for its hepato-protective, pro-regenerative, and anti-bacterial abilities,15 while ACLF is associated with hepatocyte damage, impaired liver regeneration, and bacterial infection. Theoretically, IL-22 treatment may perfectly cope with these ACLF problems, therefore we performed a pre-clinical study of IL-22Fc treatment in our ACLF model (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. IL-22Fc therapy ameliorates ACLF in mice by reprograming the impaired regeneration pathways and inducing anti-bacterial proteins.

(A) Schematic experiment timeline. Survival rates were determined and Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used for statistical analysis (**P<0.01). (B) Serum ALT and comparison of the ALT levels at 72 hours post-acute insult are shown. Blood bacterial loads are shown in the right. (C) Representative BrdU immunostaining images are shown, the percentage of BrdU+ hepatocytes was calculated. (D) Western blot analysis. (E) Hepatic and renal microcirculation were determined 72 hours post-acute insult with representative images shown on top and quantification graph below. (F) Mouse AML12 hepatocytes were stimulated with IFN-γ, IL-22Fc, or both, followed by western blot analysis. (G) Heat map of the relative hepatic expression of anti-bacterial genes in IL-22Fc and IgG2-treated mice. Student’s t-test was used for statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=8 in each group in panels B-C, n=5 in each group in panels D-E).

IL-22Fc is a recombinant fusion protein with a long half-life. Fig. S8A confirmed that IL-22 remained high (>1000 pg/ml) up to 72 hours post injection, whereas the endogenous IL-22 was below 20 pg/ml in the control group without IL-22Fc treatment. IL-22Fc treatment markedly reduced the mortality rate in ACLF mice compared to the isotype IgG-treatment (because IL-22Fc protein contains IgG2, we used isotype IgG2 as control treatment) (Fig. 6A). IL-22Fc reduced serum ALT 72 hours but not 24 and 48 hours post CCl4 injection, which was probably because IL-22Fc was injected at later time points (Fig. 6B). In addition, IL-22Fc reduced the blood bacterial load (Fig. 6B) and reduced hepatic inflammatory cytokine expressions without affecting circulating WBC (Fig. S8B–C), suggesting that IL-22Fc improves liver inflammation. Moreover, IL-22Fc increased the percentage of BrdU+ hepatocytes (Fig. 6C), which is consistent with the upregulated hepatic pro-regenerative proteins (pSTAT3, STAT3, cyclin D1) but the downregulated anti-regenerative proteins (p21) in IL-22Fc-treated group versus IgG2 group (Fig. 6D, Fig. S8D–E). Interestingly, IL-22Fc downregulated pERK and ERK expression at 48-hour time point (Fig. 6D, Fig. S8D–E). Because activation of pSTAT1/STAT1 and pSTAT3/STAT3 occurred transiently at early time points and declined at late time points, the inter-individual variation of these signals especially in the IgG group (control) in Fig. 6D was likely because both signals were measured at later time points (48 and 60 hours) and declining rates of both signals may be different between mice. Quantitation analyses revealed that cyclin D expression was higher in IL-22Fc vs. IgG2 group at 60-hour time point, which correlated well with its upstream pSTAT3 activation with higher levels in IL-22Fc vs. IgG2 group at early (48-hour) time point (Fig. S8D–E). Finally, IL-22Fc also slightly but significantly increased liver regeneration in mice with acute-on-chronic liver injury without bacterial infection or with chronic liver injury plus bacterial infection (Fig. S9). Collectively, IL-22Fc promotes liver regeneration in ACLF mice via the direct stimulation of liver regeneration and indirect inhibition of bacterial infection.

Furthermore, IL-22Fc improved hepatic and renal microcirculation from ACLF mice (Fig. 6E) and improved kidney functions as demonstrated by reducing serum BUN and renal lipocalin 2 (a marker for kidney injury) (Fig. S10). Finally, combination of antibiotic (imipenem) but not G-CSF-Fc with IL-22Fc further improved the survival of ACLF mice (Fig. S11, S12). Surprisingly, administration of G-CSF-Fc alone did not affect the survival of ACLF mice although such injection elevated circulating leukocytes (Fig. S12) and a few trials have demonstrated beneficial effects of G-CSF for ACLF patients.23, 24 Further larger multicenter trials should be performed to determine the exact effect of G-CSF on ACLF.

The above data suggest that IL-22Fc activates STAT3 but attenuates STAT1 in the liver, which was also confirmed by an in vitro experiment showing that IL-22Fc attenuated IFN-γ-induced STAT1 phosphorylation/activation in mouse hepatocytes (Fig. 6F). Moreover, we also examined hepatic expression of IL-22R and serum IL-22BP, which are known to affect IL-22 signaling.19 As illustrated in Fig. S13, hepatic IL-22R expression was upregulated in chronic CCl4-treated mice, whereas serum IL-22BP levels were comparable between control and ACLF mice. Finally, to examine the mechanisms by which IL-22Fc reduces bacterial load, we examined hepatic expression of many anti-bacterial genes25 and found that most of these genes were upregulated after IL-22Fc treatment (Fig. 6G).

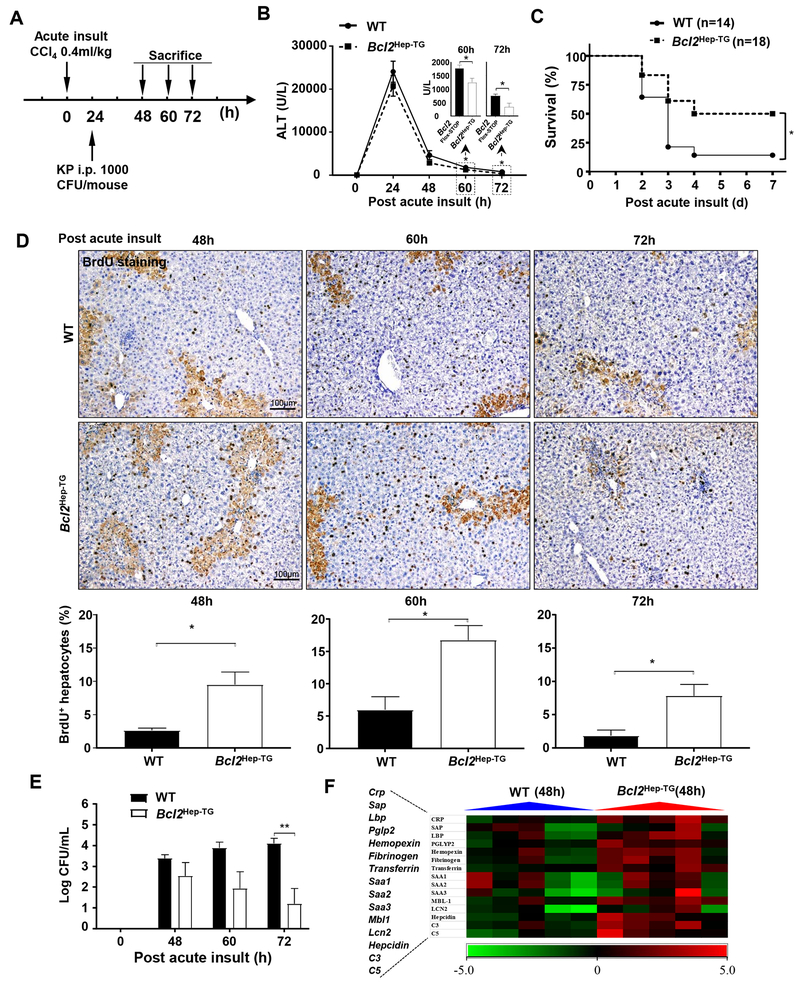

The apoptotic BCL2 protein plays a novel role in attenuating bacterial infection

To examine whether BCL2, a downstream effect of IL-22,15 also affects bacterial infection and its inhibition of liver regeneration, BCL2 transgenic (Bcl2Hep-TG) mice with hepatic BCL2 overexpression (Fig. S14A–B) and WT (Bcl2Flox-STOP) mice were acutely administrated CCl4, followed by K.P. injection (Fig. 7A). Serum ALT levels were lower in Bcl2Hep-TG versus WT mice at later time points (60 and 72 hours) but not early time points (24 and 48 hours) (Fig. 7B), which is probably because BCL2 mainly inhibits apoptosis but may not effectively attenuate necrosis induced by CCl4. Moreover, the survival and the percentage of BrdU+ hepatocytes in Bcl2Hep-TG were greater than those in WT mice post CCl4 injection (Fig. 7C–D), whereas hepatic expression of several inflammatory markers was comparable between these two groups (Fig. S14C). Finally, compared to WT, Bcl2Hep-TG mice had lower blood bacterial load (Fig. 7E), which is agreement with the higher hepatic levels of many anti-bacterial genes in these mice (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7. Bcl2Hep-TG mice have greater survival rate and liver regeneration compared to wild-type (WT) following acute liver injury and bacterial infection.

(A) Schematic diagram of CCl4 and K.P. injection procedures. Bcl2Hep-TG and WT (Bcl2Flox-STOP) mice were injected with a single dose of CCl4 and 24 hours later injection of K.P. (B) Serum ALT. (C) Survival rate was determined and Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used for statistical analysis (*P<0.05). (D) Representative images and quantification of BrdU staining in mice post the acute insult. (E) Bacterial loads in the blood were determined post the acute insult. (F) Heat map of the relative hepatic expression of anti-bacterial genes following acute insult and bacterial infection. Student’s t-test was used for statistical evaluation (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=8 in each group in panels B, D, E).

Discussion

In the present study, we developed a mouse model that recapitulates some features of clinical ACLF. By using this model, we demonstrated that liver regeneration was severely impaired in ACLF mice due to the dysregulation of the IFN-γ/STAT1 and IL-6/STAT3 pathways. This distortion of STAT1/STAT3 balance shifts injured liver from the pro-regenerative pathways to the anti-regenerative pathways, ultimately resulting in impaired liver regeneration. Interestingly, IL-22Fc therapy reprogramed the anti-regenerative into pro-regenerative pathway and ameliorated bacterial infection in ACLF mice.

A novel model to recapitulate some features of ACLF:

Compared to the existing ACLF models,10–14 the ACLF model we developed here includes chronic/acute liver injury, bacterial infection, renal injury, high short-term mortality, simulating the major pathological process of ACLF patients. The first step is the induction of chronic injury by using chronic CCl4 injection, which is also applied in some existing ACLF models.10 For the second and third steps, to our knowledge, we introduced, for the first time, a double dose of the last CCl4 injection and viable bacterial infection, which mimic acute-on-chronic liver injury and bacterial infection in ACLF patients, respectively. The survival period is approximately 5-7 days, which provides enough time for intervention studies. Because bacterial infection occurs in the majority of ACLF patients, our model with bacterial infection is also important for the intervention studies involving anti-bacterial treatment. In addition, our data suggest that a single injection of bacteria (K.P.) is a key step to induce multi-organ failure in this model because without bacterial infection, chronic-plus-acute liver injury did not drive the full course of ACLF in mice.

Liver regeneration is impaired in ACLF mice due to the distortion of STAT1/STAT3 balance:

One of major novel findings in the current study is that acute hepatic injury-induced liver regeneration was markedly suppressed in fibrotic livers, which was further inhibited by bacterial infection. Subsequently, we provided evidence suggesting that the first mechanism responsible for impaired liver regeneration in fibrotic mice was due to the tolerance of Kupffer cells to LPS stimulation and consequent impaired production of IL-6. Another critical mechanism responsible for the impaired liver regeneration in the ACLF model is the elevation of TGF-β and IFN-γ: two major cytokines that are well-known to strongly attenuate liver regeneration.17, 26 Here we demonstrated that fibrotic mice had much higher elevated or basal serum and hepatic TGF-β and IFN-γ than control mice. The elevated TGF-β apparently was due to liver fibrosis with activated hepatic stellate cells that are known to produce high levels of TGF-β, which has been shown to inhibit liver regeneration by inducing cellular senescence.26 IFN-γ is one of the most potent cytokine that strongly induces liver injury and inhibits liver regeneration by activating STAT1 and p21.17 In agreement with elevated IFN-γ, both STAT1 and p21 levels were higher in fibrotic livers versus non-fibrotic livers post-acute CCl4 administration, which likely contributes to the poor liver regeneration of fibrotic livers. Moreover, bacterial infection was found to further elevate serum IFN-γ in our ACLF model due to strong activation of innate immunity.27 Such high levels of IFN-γ likely also contribute to impaired liver regeneration in this ACLF model.

Collectively, in naïve mice, acute liver injury such as CCl4 injection strongly activates the pro-regenerative IL-6/STAT3 pathway to induce liver regeneration; whereas in ACLF mice, liver fibrosis strongly blocked the IL-6/STAT3 pathway; while bacterial infection strongly activates the IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway, thereby attenuating liver regeneration. Thus, ACLF is associated with the shift from the pro-regenerative to anti-regenerative pathway activation, ultimately leading to liver failure.

Evidence for impaired liver regeneration in ACLF patients.

It is more difficult to study liver regeneration in patients due to the heterogeneity of patients. In the current study, we stratified patients into several groups and found patients with ongoing DILI had higher serum IL-6 than patients with the early stages of HBV-ACLF, suggesting that the early stage of HBV-ACLF has impaired IL-6 response. In contrast, serum IL-6 levels were highly elevated in patients with the late stages of HBV-ACLF, which may be because these patients were associated with severe injury/inflammation and/or bacterial infection that caused IL-6 elevation. Interestingly, serum IFN-γ levels were not elevated in DILI patients but were highly elevated in ACLF patients as demonstrated in this study. Previous studies reported that alcohol-ACLF is also associated with elevated IFN-γ.28 In consistent with elevated IFN-γ, patients with HBV- or alcohol-ACLF had lower number of Ki67+ and PCNA+ hepatocytes than those with ongoing DILI, suggesting impaired liver regeneration in these ACLF patients is partly due to elevated IFN-γ.

IL-22Fc ameliorates ACLF by reprograming the regenerative pathway and attenuating bacterial infection.

IL-22Fc treatment markedly improved the survival rate, reduced the bacterial load, promoted liver regeneration, and improved hepatic and renal microcirculation in ACLF mice. One of mechanisms was because IL-22Fc therapy not only enhanced the pro-regenerative STAT3 pathway but also reduced the anti-regenerative STAT1 pathway in ACLF mice, thereby reprograming the anti-regenerative to pro-regenerative pathway. The part of reason responsible for inhibiting STAT1 was due to IL-22 activation STAT3 that is known to attenuate STAT1 activation by inducing SOCS inhibitory proteins.18 The anti-microbial role of IL-22 is exerted by inducing various anti-bacterial genes.19 In agreement with this, we demonstrated that IL-22Fc treatment upregulated hepatic expression of multiple anti-bacterial genes in ACLF mice, contributing to the anti-bacterial effects of IL-22Fc. Interestingly, our data suggest that BCL2, a downstream effector of IL-22 signaling, also partially contributes to the anti-bacterial function as hepatic overexpression of BCL2 reduced bacterial load in our ACLF model. However, how BCL2 contributes to the anti-bacterial function remains obscure. Hepatocytes are known to play an important role in attenuating bacterial infection by producing various anti-bacterial proteins.25 Remarkably, expression of these anti-bacterial genes was much higher in Bcl-2 transgenic mice versus WT mice, therefore, it is plausible to speculate that BCL2 protects against hepatocyte injury and promotes hepatocyte regeneration, thereby enhancing the antibacterial functions of hepatocytes by expressing these anti-bacterial genes.

Therapeutic potential of IL-22Fc for the treatment of ACLF patients.

Despite ACLF patients are associated with elevated IL-22 and IL-22BP (a factor that inhibits IL-22 function20), several lines of evidence suggest that IL-22Fc therapy is still effective for these patients. First, serum IL-22 levels in ACLF patients are approximately 200 pg/ml,20 while administration of pharmacologic doses of IL-22Fc elevated serum IL-22Fc levels up to 700,000 pg/ml,22, 29 which is a thousand-fold higher compared to IL-22 levels in ACLF patients. Second, despite high serum IL-22BP levels,20 healthy individuals responded very well to IL-22Fc injection, as evidenced by marked elevation of acute phase proteins,22 suggesting that endogenous IL-22BP is not enough to block the pharmacologic effects of IL-22Fc. Finally, more importantly, a phase IIb clinical trial revealed that IL-22Fc therapy was safe and improved MELD score in patients with moderate and severe alcoholic hepatitis.29 Collectively, these data support the need for clinical trials to test efficacy of IL-22Fc in ACLF patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Combination of chronic liver injury, acute hepatic insult, and bacterial infection recapitulate some features of clinical ACLF

Chronic liver injury and bacterial infection attenuate liver regeneration in ACLF due to impaired IL-6/STAT3 pathway and enhanced IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway, respectively

IL-22Fc therapy improves ACLF by promoting liver regeneration and attenuating bacterial infection

Acknowledgments

Grant support: The basic research work was performed in and supported by the intramural program of NIAAA, NIH (BG) and the clinical study of ACLF patient liver samples was performed in Shanghai Ruijing Hospital and supported by Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (YW20190002 to QX). Dr. Xiaogang Xiang was supported by a fellowship from Ruijing Hospital during his stay between 2017-2019 at the NIAAA, NIH.

Abbreviations:

- ACLF

acute-on-chronic liver failure

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- BCL2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- CCl4:

carbon tetrachloride

- CLP

cecal ligation and puncture

- DILI

drug-induced liver injury

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IL-22

interleukin-22

- INR

international normalized ratio

- K.P.

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MOF

multiple organ failure

- MT

metallothionein

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCNA

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- RT-qPCR

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RUCAM

Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method

- STAT1

transducer and activator of transcription 1

- STAT3

transducer and activator of transcription 3

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

Reference

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

- [1].Bajaj JS, Moreau R, Kamath PS, Vargas HE, Arroyo V, Reddy KR, et al. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Getting Ready for Prime Time? Hepatology 2018;68:1621–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Arroyo V, Moreau R, Kamath PS, Jalan R, Gines P, Nevens F, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wu T, Li J, Shao L, Xin J, Jiang L, Zhou Q, et al. Development of diagnostic criteria and a prognostic score for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut 2018;67:2181–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sarin SK, Choudhury A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: terminology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13:131–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hernaez R, Sola E, Moreau R, Gines P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: an update. Gut 2017;66:541–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gustot T, Jalan R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol 2019;70:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fernandez J, Acevedo J, Wiest R, Gustot T, Amoros A, Deulofeu C, et al. Bacterial and fungal infections in acute-on-chronic liver failure: prevalence, characteristics and impact on prognosis. Gut 2018;67:1870–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Claria J, Arroyo V, Moreau R. The Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Syndrome, or When the Innate Immune System Goes Astray. J Immunol 2016;197:3755–3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yang L, Wu T, Li J, Li J. Bacterial Infections in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Semin Liver Dis 2018;38:121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li F, Miao L, Sun H, Zhang Y, Bao X, Zhang D. Establishment of a new acute-on-chronic liver failure model. Acta Pharm Sin B 2017;7:326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kuhla A, Eipel C, Abshagen K, Siebert N, Menger MD, Vollmar B. Role of the perforin/granzyme cell death pathway in D-Gal/LPS-induced inflammatory liver injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;296:G1069–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li X, Wang LK, Wang LW, Han XQ, Yang F, Gong ZJ. Blockade of high-mobility group box-1 ameliorates acute on chronic liver failure in rats. Inflamm Res 2013;62:703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Balasubramaniyan V, Dhar DK, Warner AE, Vivien Li WY, Amiri AF, Bright B, et al. Importance of Connexin-43 based gap junction in cirrhosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol 2013;58:1194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tripathi DM, Vilaseca M, Lafoz E, Garcia-Caldero H, Viegas Haute G, Fernandez-Iglesias A, et al. Simvastatin Prevents Progression of Acute on Chronic Liver Failure in Rats With Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1564–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gao B, Xiang X. Interleukin-22 from bench to bedside: a promising drug for epithelial repair. Cell Mol Immunol 2019;16:666–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Michalopoulos GK. Hepatostat: Liver regeneration and normal liver tissue maintenance. Hepatology 2017;65:1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sun R, Gao B. Negative regulation of liver regeneration by innate immunity (natural killer cells/interferon-gamma). Gastroenterology 2004;127:1525–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hong F, Jaruga B, Kim WH, Radaeva S, El-Assal ON, Tian Z, et al. Opposing roles of STAT1 and STAT3 in T cell-mediated hepatitis: regulation by SOCS. J Clin Invest 2002;110:1503–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol 2011;12:383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schwarzkopf K, Ruschenbaum S, Barat S, Cai C, Mucke MM, Fitting D, et al. IL-22 and IL-22-Binding Protein Are Associated With Development of and Mortality From Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:392–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li H, Feng D, Cai Y, Liu Y, Xu M, Xiang X, et al. Hepatocytes and neutrophils cooperatively suppress bacterial infection by differentially regulating lipocalin-2 and neutrophil extracellular traps. Hepatology 2018;68:1604–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tang KY, Lickliter J, Huang ZH, Xian ZS, Chen HY, Huang C, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and biomarkers of F-652, a recombinant human interleukin-22 dimer, in healthy subjects. Cell Mol Immunol 2019;16:473–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Simonetto DA, Shah VH, Kamath PS. Improving survival in ACLF: growing evidence for use of G-CSF. Hepatol Int 2017;11:473–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shasthry SM, Sharma MK, Shasthry V, Pande A, Sarin SK. Efficacy of Granulocyte Colony-stimulating Factor in the Management of Steroid-Nonresponsive Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Hepatology 2019;70:802–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhou Z, Xu MJ, Gao B. Hepatocytes: a key cell type for innate immunity. Cell Mol Immunol 2016;13:301–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bird TG, Muller M, Boulter L, Vincent DF, Ridgway RA, Lopez-Guadamillas E, et al. TGFbeta inhibition restores a regenerative response in acute liver injury by suppressing paracrine senescence. Sci Transl Med 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shtrichman R, Samuel CE. The role of gamma interferon in antimicrobial immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol 2001;4:251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Spahr L, Garcia I, Bresson-Hadni S, Rubbia-Brandt L, Guler R, Olleros M, et al. Circulating concentrations of interleukin-18, interleukin-18 binding protein, and gamma interferon in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Int 2004;24:582–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arab J, Sehrawat T, Simonetto D, Verma V, Feng D, Tang T, et al. An open label, dose escalation study to assess the safety and efficancy of IL-22 agonist F-652 in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2019; on line [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.