Abstract

Neonates and immunosuppressed/immunocompromised pediatric patients are at high risk of invasive fungal diseases. Appropriate antifungal selection and optimized dosing are imperative to the successful prevention and treatment of these life-threatening infections. Conventional amphotericin b was the mainstay of antifungal therapy for many decades, but dose-limiting nephrotoxicity and infusion-related adverse events impeded its use. Despite the development of several new antifungal classes and agents in the past 20 years, and their now routine use in at-risk pediatric populations, there are limited data to guide optimal dosing of antifungals in children. This paper reviews the spectra of activity for approved antifungal agents and summarizes the current literature specific to pediatric patients regarding pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data, dosing, and therapeutic drug monitoring.

1. INTRODUCTION

With the development of remarkable advances in life-saving and -prolonging treatments and technologies for premature, immunocompromised, and critically ill infants and children, the number of pediatric patients at-risk for invasive fungal disease (IFD) has increased over time. As a result, more and more children are receiving antifungal agents, either for treatment or prevention of IFD [1, 2]. Over the past few decades, therapeutic options have expanded and there has been a shift away from conventional antifungal drugs (e.g. amphotericin products) towards the use of newer agents, such as triazoles and echinocandins [1]. However, pediatric-specific studies are still needed to confirm the therapeutic targets associated with optimal effectiveness and safety for many of these agents, particularly the newer triazole drugs.

Successful treatment of any infection requires the provision of an antimicrobial agent at a dose that achieves therapeutic concentrations at the site of infection. In cases of IFD, substantial inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetics (triazoles), narrow therapeutic windows (amphotericin products), and limited oral bioavailability (amphotericin products, echinocandins) complicate antifungal selection and dosing decisions. Further challenging dose optimization in pediatrics is the maturation of hepatic and renal clearance mechanisms, which can significantly impact the pharmacokinetics (PK) of drugs in infants and younger children [3]. Ultimately, clinicians need to be cognizant of the myriad of patient- and drug-related factors influencing antifungal PK in pediatric patients.

The goals of this practical review are to describe the spectrum of activity and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) of systemic antifungal agents currently available in children. We will detail dosing recommendations from infancy to adolescence for drugs currently in use and evaluate the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for each. We will focus on pediatric data, but highlight information that can be extrapolated from adults, as needed. Ultimately, we hope that this review will provide clinicians and pharmacists with useful information regarding the current state of antifungal clinical pharmacology in pediatrics.

2. POLYENES

2.1. Spectrum of activity and clinical indications

Amphotericin B (AmB) is the oldest of the systemic antifungal drugs and has long been considered first-line for treatment of IFD due to its potent and broad fungicidal activity. AmB is a polyene macrolide that binds to ergosterol, the principle sterol present in fungal cell membranes, causing membrane disruption, loss of cell contents, and fungal cell death [4]. It is active against most pathogenic yeasts and molds. Among Candida species, however, activity against C. lusitaniae [4] and C. auris is variable [5, 6]. And, while AmB provides the most comprehensive coverage of pathogens from the Mucorales order, increased resistance has been reported with some of the species in this order such as those in the genera of Cunninghamella and Rhizopus [7].

Four AmB products have been produced for clinical use, all of which have identical spectra of activity: AmB deoxycholate (D-AmB), also known as conventional AmB, and three lipid-based formulations - AmB colloidal dispersion (ABCD), AmB lipid complex (ABLC), and liposomal AmB (L-AmB). D-AmB was the first formulation made available for clinical use in the 1950s and served as the cornerstone of antifungal therapy for several decades. Dose-limiting side effects of D-AmB, namely nephrotoxicity and electrolyte disturbances, as well as infusion-related reactions (phlebitis, rigors), were major limitations of D-AmB use and led to the development of lipid formulations in the 1990s. Each of the lipid-based formulations are complexed to lipids in different ways, which protects tissues from direct toxicity of free AmB.

Nephrotoxicity is the major adverse event of all AmB products and a significant deterrent to their use. The lipid-based formulations of AmB have comparable efficacy to D-AmB but improved safety profiles compared to D-AmB [8–10]. In a Cochrane review involving 4 trials and 395 participants, lipid formulations were associated with a significant decrease risk of nephrotoxicity: relative risk 0.47 (95% CI 0.21 – 0.90) [11]. Due to their improved safety, lipid preparations are preferred over D-AmB for prevention and treatment of most IFD in children. D-AmB remains the product of choice, however, for treatment of neonatal candidiasis [12], due to data from observational studies showing decreased mortality with D-AmB compared to lipid formulations [13], as well as cryptococcal meningoencephalitis [14]. Lipid preparations, particularly L-AmB, remain first-line for the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) candidiasis outside of the neonatal period [12], mucormycosis [15], and severe endemic mycoses including pulmonary, disseminated, or CNS blastomycosis [16], osseous coccidioidomycosis [17], and acute pulmonary histoplasmosis [18]. AmB is also an alternative therapy for treatment of invasive aspergillosis (IA) in patients who cannot receive voriconazole [19].

2.2. Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics

Amphotericin B exhibits concentration-dependent fungicidal activity and prolonged suppression of fungal growth after the concentration has fallen below the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the infecting organism [20]. The PK/PD parameter best associated with killing of Candida and Aspergillus species in preclinical studies has been the Cmax/MIC ratio [20, 21]. As a result, fungicidal activity is promoted through the administration of large dosages that achieve optimal peak concentrations at the site of infection. Unfortunately, dose- and infusion-related toxicities preclude the use of overly large AmB dosages in the clinical setting and recommended dosages for all AmB formulations are driven based on tolerability.

Each of the AmB products have unique PK properties (Table 1). Conventional AmB is complexed with deoxycholate, a detergent, to make the drug soluble in water. It quickly disassociates from its carrier after infusion and becomes highly (>95%) protein bound [22]. There is large variability in the PK of D-AmB among children, with an inverse relationship between age and clearance (CL) [23–25]. As a result, serum concentrations of AmB in infants are lower than in older children and adults given comparable D-AmB doses [23, 24]. Peak serum concentrations tend to be around 1.5–3.0 mg/L following administration of a 1 mg/kg dose [26], although there are sizable differences in serum concentrations across pediatric patients [23, 24]. D-AmB has a biphasic plasma concentration profile with an initial half-life of 9–26 hours [23, 24, 27] and a terminal half-life as long as 15 days [22]. The plasma half-life has been reported to increase over the course of therapy, particularly in premature infants [24], suggesting that tissue accumulation may occur with prolonged treatment. AmB is not metabolized to any clinically relevant extent and two-thirds of D-AmB doses are excreted unchanged in the urine and feces [28].

Table 1.

Administration information and pharmacokinetic properties of amphotericin B products.

| Amphotericin B deoxycholate (D-AmB) | Amphotericin B colloidal dispersion, Amphotericin B cholesteryl sulfate complex (ABCD) | Amphotericin B lipid complex (Abelcet®, ABLC) | Liposomal amphotericin B (Ambisome®, L-AMB) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved pediatric indications | Treatment of patients with progressive, potentially life-threatening fungal infections: aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, North American blastomycosis, systemic candidiasis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, zygomycosis (including mucormycosis due to susceptible species of the genera Absidia, Mucor, and Rhizopus), and infections due to related susceptible species of Conidiobolus, Basidiobolus, and sporotrichosis* | Treatment of invasive aspergillosis in patients who have failed D-AmB treatment, or who have renal impairment or experience unacceptable toxicity which precludes treatment with D-AmB in effective doses* | Treatment of invasive fungal infections in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of D-AmB therapy* | Empirical therapy for presumed fungal infection in febrile, neutropenic patients*# Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV infected patients* Treatment of patients with Aspergillus species, Candida species and/or Cryptococcus species infections refractory to D-AmB, or in patients where renal impairment or unacceptable toxicity precludes the use of D-AmB* Treatment of severe systemic and/or deep mycoses# Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis*# |

| Pediatric dosage | 0.25–1.5 mg/kg once daily (1 mg/kg/dose is standard starting dose; max daily dose: 1.5 mg/kg/day)* | 3–4 mg/kg once daily* | 5 mg/kg once daily* | 3 mg/kg once daily (empirical therapy in fever neutropenia)*# 3–5 mg/kg once daily (treatment of systemic fungal infections)*# 5 mg/kg once daily (mucormycosis)*; dosages up to 10 mg/kg can be considered for CNS mucormycosis, balancing risks/benefits[15] 6 mg/kg once daily (cryptococcal meningitis)* |

| Administration | Infuse over 4–6 hours | Initially infuse at 1 mg/kg/hr; may increase rate based on patient tolerability | Infusion rate: 2.5 mg/kg/h | Infuse over 60–120 minutes |

| Mean pharmacokinetic properties | ||||

| Cmax(mg/L) | 2.9 [23] | 2.8a [33] | 2.05b[31] | 46.2c [226] |

| AUC24 (mg*L/h) | 24.1–26.3 [26, 27] | 7.1 [33] | 15.3b[31] | 351c [226] |

| T1/2 (h) | 18.1–26.4 [23, 27] | 31.5 [33] | 395 [32] | 12.6c [226] |

| Vd(L/kg) | 0.4–4.1 [23, 24, 27] | 4.6 [33] | 10.5 [32] | .15 – 1.2c [50, 226] |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 0.2–3.4 [23, 24, 27] | 2.4 [33] | 6.7 [32] neonatesd 3.6 [31] children |

.16 – .34c [50, 226] |

| PK/PD target | Cmax/MICe | Cmax/MICe | Cmax/MICe | Cmax/MICe |

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximal concentration; PK/PD, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics; Vd, volume of distribution.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration labeling.

European Medicines Agency labeling.

Cmax derived from simulations of individual PK parameter predictions among 12 adult and pediatric patients; AUC24, T1/2, Vd and CL estimated in 5 children receiving 7–7.5 mg/kg of ABCD [33].

Mean day 7 value for Cmax and AUC0–24 reported, mean day 42 value for CL reported; 6 children included in study [31].

Cmax, AUC0–24, and T1/2 reported in 13 children administered 5 mg/kg/dose. Ranges for Vd and CL reported includes 39 children administered 2.5–10 mg/kg/dose [226].

Mean estimated CL reported in 28 neonates.

Specific Cmax/MIC ratio associated with optimal efficacy not established.

Lipid formulations of AmB were developed to mitigate toxicities related to D-AmB and facilitate administration of larger dosages. A detailed summary of the different formulations and their properties is beyond the scope of the current review, but can be found elsewhere [9, 29]. Compared with D-AmB, both ABCD and ABLC attain lower peak plasma concentrations, smaller AUCs, larger volumes of distribution (Vd), and shorter terminal half-lives in animal models, likely due to rapid distribution of drug into tissues [30]. These lipid formulations are not well-studied in children, however. Among 3 children with hepatosplenic candidiasis treated with 2.5 mg/kg of ABLC [31], steady-state plasma concentrations were low: mean Cmax 1.7–2.0 mg/L on days 7–42 [31]. In a separate population PK study of 28 neonates treated with ABLC [32], CL was .399 L/h/kg, resulting in similar plasma concentrations to older children and adults. Meanwhile, in a study involving 5 children <13 years of age treated with 7–7.5 mg/kg of ABCD [33], PK parameter estimates were comparable to those in children >13 years and adults receiving the same dosages [33].

Compared to D-AmB, L-AmB has a lower volume of distribution [28], and achieves higher peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) and larger area-under-the-curve (AUC) [30]. At a dosage of 5 mg/kg, mean day 1 AUC0–24 was 351 (+/−445) μg/mL*h among 13 immunocompromised pediatric patients; this contrasts with a mean AUC0–24 of 24.1 μg/mL*h in children treated with 1 mg/kg of D-AmB [26]. Unlike D-AmB, which circulates predominantly as protein bound drug (e.g. biologically inactive drug), L-AmB circulates in 3 forms: unbound, protein-bound, and liposome-associated drug. While total plasma concentrations are high with L-AmB, the majority of drug is sequestered within liposomes [22], resulting in a very low unbound fraction (.005) in plasma [34]. The high fraction of liposome-associated AmB leads to a prolonged circulating half-life and protects individuals from direct toxic effects of free AmB, while providing a depot for delivery of AmB to tissues and fungal targets over an extended period of time [22, 34]. Hence, L-AmB activity is believed to persist long after cessation of therapy.

Complexing AmB into lipids has significant effects on drug distribution to tissues. All formulations of AmB distribute well into the liver and spleen owing to uptake by circulating macrophages [35, 36], but have distinct intrapulmonary disposition patterns [37]. Compared to other formulations, ABLC distributes best to lung tissue in animal models [37], achieving concentrations in lung tissue several-fold that of plasma. The lung tissue:plasma ratio for all other AmB formulations is <1 [37]. Epithelial lung fluid (ELF) concentrations in critically ill adults, however, are comparable among lipid-based AmB products [38]. The impact of the differential distribution of AmB products in lung tissue and ELF on therapeutic outcomes is unknown.

Lipid preparations of AmB were specifically designed to be renoprotective, raising concerns about their effectiveness in the treatment of fungal urinary tract infections. In a study of 30 neonates with invasive candidiasis [32], AmB concentrations in the urine following 2.5–5.0 mg/kg of ABLC were higher than the MIC for most Candida isolates [32]. Despite these findings, clinical failures with lipid AmB formulations have led to continued recommendations against use of these products in the treatment in fungal urinary tract infections [39].

Penetration of AmB products into the CNS is of particular clinical importance. However, there are conflicting recommendations regarding the preferred AmB agent for treatment of various CNS infections, which is largely driven by a paucity of comparative effectiveness studies rather than demonstration of clinical superiority of one agent over another. In the U.S., D-AmB is the preferred initial drug for treatment of CNS candidiasis in infants [12], but D-AmB and L-AmB are given equivalent B-II recommendations in Europe [40]. Meanwhile, D-AmB remains the drug of choice for treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in all ages [14]. However, L-AmB is the preferred agent for treatment of CNS infections in children outside of the neonatal period including CNS candidiasis [12, 40], mucormycosis [15], and histoplasmosis [18]. In a preclinical rabbit model of Candida meningoencephalitis, L-AmB achieved significantly higher brain tissue concentrations than the other AmB products, while CSF concentrations were comparable across all of the products [30]. In this study, D-AmB and L-AmB were equally effective at treating Candida meningoencephalitis and more effective than ABCD or ABLC [30].

2.3. Pediatric Dosing

Each of the four AmB products have unique pharmacological characteristics and the specific dosage differs by agent (Table 1). Despite these differences, dosing is weight-based according to actual body weight for each agent, without a maximum recommended dose [41]. However, a recently published population PK study of L-AmB in morbidly obese adult patients suggests that a fixed dose of 300 or 500 mg may be more appropriate than 3–5 mg/kg for individuals >100kg [42], as CL is not affected by body weight. All of the AmB products are administered once daily regardless of age and, since only small amounts of AmB are excreted in urine and bile, dose adjustments are not required in the setting of renal or hepatic dysfunction. AmB is also not dialyzed and therefore doses of AmB products do not need to be adjusted in patients receiving renal replacement therapy. D-AmB should be avoided, if possible, in the setting of known kidney disease/injury since it is the most nephrotoxic of the formulations.

Standard dosing of D-AmB in neonates and children is 1 mg/kg/dose, but dosages as high as 1.5 mg/kg could be considered in serious or resistant infections. To reduce the likelihood of infusion reactions, D-AmB should always be infused as a slow infusion (over at least 2–6 hours). Some studies have also reported a decreased risk of nephrotoxicity with administration of D-AmB as a continuous infusion [43], although this finding is not universal [44]. While AmB demonstrates concentration-dependent killing, the use of continuous infusions has not been associated with inferior microbiologic or clinical outcomes [44].

Similar to D-AmB, serum concentrations of L-AmB were lower in infants and children than in adults given comparable doses in one report [45]. However, data are conflicting as a more recent study found that L-AmB pharmacokinetics were similar in adult and pediatric patients [46]. Despite the significant inter-patient variability in drug concentrations of L-AmB in children, there is insufficient evidence to support a need for different dosing in pediatric and adult patients. Higher L-AmB dosages should be considered when treating resistant or more serious infections in children, such as CNS infections. A dosage of 6 mg/kg of L-AmB is recommended for treatment of cryptococcal meningitis to ensure adequate CNS penetration [47]. Meanwhile, dosages of 5–10 mg/kg are recommended by European guidelines for treatment of CNS mucormycosis in children [15]. Dosages above 5 mg/kg demonstrate nonlinear PK in children and significantly higher drug exposures are attained with these dosages than at dosages <5 mg/kg [48, 49]. Thus, it is unclear whether there are other indications for which dosages >5 mg/kg should be used. There are insufficient pediatric data to identify specific clinical scenarios in which individualized (i.e. higher or lower) dosages of ABCD and ABLC are warranted.

2.4. Therapeutic drug monitoring – adverse events

TDM is not generally available for AmB for a number of reasons. First, there are no well-established PK/PD targets associated with improved clinical outcomes for any of the AmB products. Although AmB is concentration-dependent and higher Cmax/MIC ratios have been reported in children successfully treated with L-AmB [50], specific targets have not been established to inform dose adjustments for AmB products. Second, while AmB products are associated with nephrotoxicity, toxicodynamic thresholds have also not been specified. Lastly, because the AmB product being used will dictate what type of drug measurement assay should be performed - total drug, protein-bound drug, liposome-associated drug, unbound drug – AmB concentrations are not easily interpretable. For TDM, it is important to be able to accurately identify the active fraction of total drug concentrations (i.e. with L-AmB, both liposome-associated and unbound drug are biologically active). Therefore, assays need to be able to specify different forms of AmB to inform dose adjustments.

Nephrotoxicity and electrolyte wasting are the principal adverse events associated with AmB administration. Nephrotoxicity occurs in 15% to >50% of children treated with D-AmB [51], although nephrotoxicity is less frequent in children compared to adults [51]. AmB-associated nephrotoxicity clinically manifests as increased blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine, as well as electrolyte wasting [52, 53], primarily in the form of potassium wasting. Hypokalemia requiring potassium supplementation occurs in up to 40% of children treated with high-dose L-AmB (>3 mg/kg) therapy [46, 49, 54]. Therefore, close laboratory monitoring and avoidance of other nephrotoxic medications, when possible, is advised in all patients treated with AmB products.

Infusion-related reactions are also encountered with administration of AmB products, particularly when administered as a rapid infusion. Fever, rigors, chills, myalgias, arthralgias, and nausea are common and believed to be due to histamine or cytokine release in response to therapy [55]. Hypotension, hypoxia, and cardiac arrhythmias are much rarer. Among the AmB products, infusion-related toxicities are particularly problematic for ABCD. In one trial [56], infusion-related events occurred in more than half of recipients of ABCD, leading to discouragement of its use in some guidelines [19].

3. AZOLES

3.1. Spectrum of activity and clinical indications

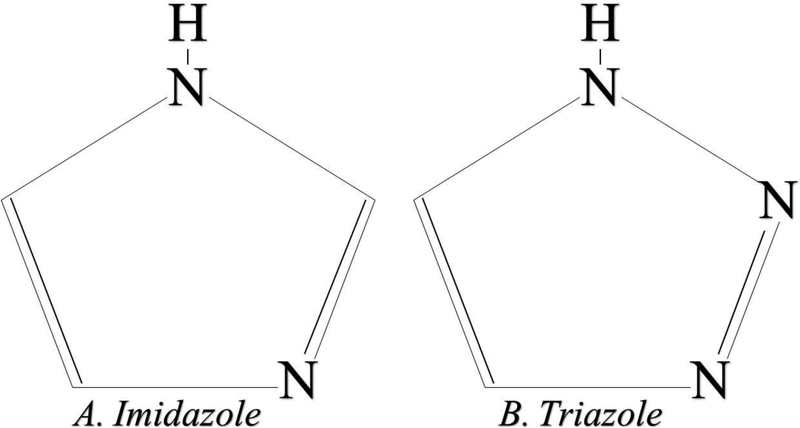

The azole antifungals are classified into two distinct groups, the imidazole and the triazole antifungals. Structurally, the main difference between the two groups is the number of nitrogens in the 5-membered ring (Figure 1), where imidazoles have two non-adjacent nitrogens and triazoles have three nitrogens. However, the mechanism of action for both classes of azole antifungals is to inhibit the cytochrome P450-dependent 14-α-sterol demethylase, which interrupts ergosterol biosynthesis of fungal cell membranes and inhibits cell growth [57].

Figure 1.

Core structure of azole agents.

The clinical indications of imidazoles are mostly limited to topical uses due to their spectrum of activity, adverse effect profile when systemically administered, potency, or solubility [58]. Therefore, imidazoles are frequently administered as topical formulations for the treatment of dermatophytes and vaginal or oral candidiasis (Table 2). Ketoconazole is the only imidazole administered both topically and systemically. However, due to its drug-drug interaction profile, it has fallen out of favor compared to triazole antifungals and is no longer administered systemically in developed countries due to safer alternatives.

Table 2.

Clinical spectrum of azole antifungal agents

| Clotrimazole | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Econazole | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Ketoconazole | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Miconazole | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Tioconazole | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Fluconazole | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Isavuconazole | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Itraconazole | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Posaconazole | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Voriconazole | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Triazole antifungals have improved spectrum of activity compared to imidazoles. Fluconazole was the first triazole developed and has activity against most yeasts and thermally dimorphic fungi (those that present as yeasts in temperatures greater than 37°C), such as Histoplasma spp. and Blastomyces spp. [59]. It is used extensively in neonates for prevention and treatment of invasive candidiasis [60]. Newer triazoles, such as itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole, have extended spectra of activity against invasive filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus spp., but resistance has begun to emerge [61, 62]. The most recently developed second generation triazole, isavuconazole, was developed to overcome resistance that limits efficacy of triazole treatment. However, as detailed below, there are limited studies to establish the clinical role of isavuconazole in children. Clinical indications for triazole antifungals differ by agent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Administration and pharmacokinetic information for triazole agents.

| Available Formulations | IV Solution Oral Tablet Oral Suspension |

Oral Tablet Oral Capsule Oral Solution SUBA capsule |

IV Solution Oral tablet Oral Suspension |

IV Solution Oral Suspensiona Delayed Release Tableta |

IV Solution Oral Capsule |

| Approved Pediatric Age Range | ≥ 6 months old | ≥ 6 months old | ≥ 2 years old | ≥ 13 years old | n/a |

| Approved Pediatric Indications | Cryptococcal infections including meningitis*# Invasive candidiasis*# Oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis*# Prophylaxis of Candida infections in immunocompromised children# or those undergoing bone marrow transplantation* |

Aspergillosis*# Blastomycosis* Cryptococcal infections including meningitis# Dermatophytoses# Histoplasmosis*# Onychomycoses*# Oropharyngeal and vulvovaginal candidiasis# Pityriasis versicolor# Systemic candidiasis# |

Prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in high-risk allogeneic hematopoieticcell transplant recipients# Treatment of: Invasive aspergillosis*# Candidemia and candidiasis*# Scedosporium apiospermum*# Fusarium species*# |

Prophylaxis against invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in high-risk patients*# Treatment of: Invasive aspergillosis# Fusarosis# Chromoblastomycosis# Coccidioidomycosis# Oropharyngeal candidiasis*# |

n/a |

| Pediatric Dosage | Intravenous/Enteral: 25 mg/kg loading dose followed by 12mg/kg/day | 3–5 mg/kg/day either as one dose or divided in two doses [112, 113] | Children & Adolescents <50 kg: Intravenous: 9 mg/kg q12 hours × 1 day, followed by 8 mg/kg IV q12 hours*# Enteral: 9 mg/kg q12 hours (maximum dose 350 mg)*# Adolescents >50 kg: refer to adult dosing*# |

Not fully defined per guidelines; dosing in children >13 years as for adults Adult dosing: Prophylaxis of invasive Asperaillus and Candida infections*#: Intravenous: 300mg IV BID on day 1, then 300mg IV qday Oral suspension: 200mg 3 times daily Delayed-release tablet: 300mg twice daily on day 1, then 300mg once daily Oropharyngeal candidiasis: Oral suspension: 100mg twice a day on day 1, then 100mg daily*; 200mg once daily on day 1, then 100 mg daily# Oropharyngeal candidiasis refractory to itraconazole and/or fluconazole*: Oral suspension: 400 mg twice daily Refractory invasive fungal infections#: Intravenous: 300mg IV BID on day 1, then 300mg once daily# Oral suspension: 200mg four times per day# Delayed-release tablet: 300mg twice daily on day 1, then 300mg once daily |

No currently approved pediatric dosage; 10 mg/kg (maximum 372 mg) dose produces similar exposures compared to that observed in adults [117] Adult dosing: Intravenous/Enteral: Loading Dose: 372 mg isavuconazole sulfate (200 mg isavuconazole) IV/PO q8 hours × 6 doses Maintenance Dose: 372 mg IV/PO qday 12 to 24 hours after the last loading dose |

| Mean pharmacokinetic properties | |||||

| Bioavailability | >90% [227] | 55% [227] | > 90% adults [79, 227] 44–66% children [86, 87] | >98% [227] | 98% [106] |

| Metabolism | Minimal, ~11%, mainly by UGT2B7 [67, 228] | 99% Hepatic Metabolism via CYP3A4 [57] | 98% Hepatic Metabolism via CYP3A4, 2C19, 2C9, & FMO3 [81, 82, 88] | 17–34% Hepatic Metabolism via UGT1A4 [98, 99] | 99% plasma esterases to active metabolite Isovuconazole 99% hepatic metabolism via CYP3A4 [107, 108] |

| Elimination | Parent: 80%−90% Renal elimination [66, 68, 228] | Parent: 3%−18% Biliary elimination <1% Renal elimination unchanged Metabolites: 54% biliary elimination, 35% renal elimination | Parent: <2% Renal elimination Metabolites: >80% Renal Elimination [79] | Parent: 66.3% Hepatic elimination <1% Renal elimination Metabolites: 11% Biliary elimination 13% Renal elimination [98, 99] | Parent: <1% Renal elimination unchanged Metabolites: 45% biliary elimination, 45% renal elimination [106] |

| Protein Binding | 11% [66, 228] | 99% [227] | 58% [57, 79, 227] | >95% [57] | 98%−99% [106, 107] |

| CL (L/h/kg) | 0.008–0.037 [227] | 0.6–0.7 [227] | 0.38–0.58 [86] | 0.5–1.4 [96, 97] | NR |

| Vd (L/kg) | 0.7–2.25 [66, 111, 227] | 5.1–15.5 [227] | 0.81–2.2 [86] | 11.2 [96] | NR |

| Half-life (h) | 16.8–88.6 [66, 111] | 28–104 [227] | 3.1–29.2 [229] | NR | NR |

| PK/PD target(s) | n/a | Trough > 0.5 mg/L | Trough 1–6 mg/L | Prophylaxis trough > 0.7 mg/L Treatment trough > 1 mg/L | Limited exposure-response relationship, so routine TDM is not currently advised |

Abbreviations: Vd, volume of distribution; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring

U.S. Food & Drug Administration labeling

European Medicines Agency labeling

Enteral formulations should be taken with food or acidic beverage

3.2. Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics

The efficacy of azoles is concentration-independent [63], with the primary PD endpoint associated with clinical outcomes after azole administration being the exposure to minimum inhibitory concentration ratio, or AUC0–24/MIC. Azoles also exhibit significant post- antifungal effects [63]. For invasive candidiasis, clinical success is achieved when AUC0–24/MIC of the unbound azole is greater than 25 [64]. This averages out to an azole unbound concentration close to the MIC of 1 over 24 hours [64]. In contrast, for Aspergillus infections, the proposed AUC/MIC endpoint should be between 2 to 11 [64].

Pharmacokinetic profiles for the triazole antifungals vary. Fluconazole is a hydrophilic compound with low protein binding compared to the others other agents. It is well absorbed and its hydrophilicity limits its Vd to a volume similar to that of total body water. It readily passes through the blood brain barrier and has a concentration in cerebrospinal fluid up to 80% of what is observed in the plasma in adults [65]. Fluconazole is bound primarily to α1-acid glycoprotein [66], and undergoes only minimal metabolism (~11%) by UGT2B7 [66, 67]. Overall, fluconazole is eliminated primarily unchanged with 80–90% of parent eliminated in the urine [66, 68].

Itraconazole is a weak base that is highly lipophilic with poor water solubility. There is large variability in bioavailability based on formulation. Capsule formulations require a low gastric pH for dissolution and therefore absorption is appreciably affected by gastric acidity [69, 70]. Coadministration with a H2-receptor antagonist, such as famotidine or rantidine, decreases both the Cmax and AUC0–24 by approximately half [71]. A lower gastric pH, such as after a meal, along with longer gastric emptying time and a higher fat content, doubles the bioavailability compared to the fasted state, and increases the exposure by >160% [72]. Itraconazole has a highly variable PK profile, making it difficult to achieve target concentrations. After oral administration, it has lower accumulation in children <12 years old compared to adults, with the youngest children exhibiting the lowest plasma concentrations, which could be due to maturation in intestinal metabolism or absorption [73, 74]. Another study of itraconazole in children also demonstrated high PK variability and demonstrated a correlation between itraconazole PK and ethnicity and gender [75]. Itraconazole is highly protein bound mostly to albumin and also to red blood cells [76]. Despite this high protein binding, it distributes extensively into tissues due to its lipophilic nature, which is shown by its high Vd and concentrations 2–3 times higher in tissues than plasma [77]. However, it poorly distributes into the CSF, eye fluid, and saliva [77]. It undergoes metabolism by CYP3A4 to 30 different metabolites, with hydroxyl-itraconazole being the primary metabolite that also displays antifungal activity. It has negligible renal elimination of either parent or metabolites, with most elimination into the feces [76].

Voriconazole is a structural analogue to fluconazole, but with a wider spectrum of activity. It was the first triazole to demonstrate superior efficacy and safety compared to D-AmB in the treatment of IA [78], and is now the first-line treatment for IA in both children and adults [19]. In adults, it is well-absorbed with a bioavailability of approximately 96% [79]. Absorption is decreased when administered with food, with a reduction in Cmax and AUC0–24 of up to 60% and 80%, respectively [80]. It is extensively metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 [79, 81, 82]. Almost all of its metabolites, including the main circulating metabolite, voriconazole N-oxide, are renally eliminated [79]. Studies have suggested that polymorphisms in CYP2C19, including poor and ultra-rapid metabolizers, contribute in part to this high variability [83, 84]. The PK of voriconazole in children differs significantly from that in adults. Overall, variability of AUC, Cmax, and clearance ranges from 32% to 175% in adults and children [79, 85]. While bioavailability is high in adults, it is significantly reduced to 44–65% in children [86, 87]. One physiologically-based PK model suggested that first-pass intestinal metabolism could be responsible for the lower bioavailability in pediatric patients [88]. In children, voriconazole has linear PK, which has been attributed to the higher abundance and capacity of hepatic CYP2C19 and FMO3 in children compared to adults, yielding a clearance 3-fold higher in children aged 2–12 years old compared to that of adults [82]. In preclinical studies [89], autoinduction has been observed, a process by which metabolism of the drug increases over time; this has also been reported in clinical cases with declining concentrations over time, as well [90, 91].

Posaconazole was initially derived from itraconazole and is also highly lipophilic. It is available in a delayed-release tablet, oral suspension, and intravenous formulation. Posaconazole’s lipophilicity allows it to distribute extensively into the tissues, conferring a high Vd and a long terminal half-life. But, as with itraconazole, it is highly protein bound to albumin and its penetration into CSF fluid is poor. Posaconazole lipophilicity also contributes to large variability in PK parameters, such as clearance and bioavailability, which can vary between subjects up to 50% and 80%, respectively [92–95]. Two studies demonstrated that the clearance of posaconazole in children 6 months to 13 years old was approximately 0.8 L/h/kg [96, 97], an almost 4-fold increase compared to adults, and variability between subjects was over 60%. Posazonazole undergoes hepatic metabolism by glucuronidation, but only to a small degree, with approximately 17%−34% of the total dose converted to glucurconide metabolites and the rest remaining unchanged as parent compound eliminated primarily through the feces [98, 99]. Despite not requiring the CYP450 pathway for metabolism, posaconazole has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 [100, 101].

Overall, posaconazole absorption is affected by meals for both the suspension and tablet formulations, increasing the bioavailability up to 168% to 290% depending on fat content of the meal [102]; administration with a high fat meal increases the gastric residence time and increases solubility. However, bioavailability is saturable such that increasing the dose decreases the percent absorbed [96]. As a result, bioavailability of posaconazole increases when the total daily dose is divided over multiple doses, with an increase of 2- and 3-fold higher after administration every 12 hours and 6 hours, respectively [93]. There are important differences in the bioavailability of posaconazole between the suspension and delayed-release tablet. In a trial of posaconazole as prophylaxis in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients, trough levels were significantly higher in children receiving tablet than suspension [103]. A recently published nonrandomized trial reported that dosages as high as 18 mg/kg/day divided every 8 hours failed to achieve a therapeutic target of Cave of 500–2000 ng/mL in 90% of children treated with the oral suspension [104]. Similarly, simulations performed in separate study reported that 200 mg in tablet form taken three times per day would result in 72% probability of target attainment (Cmin >1 mg/L) for children 7–12 years of age, while the same dosage in suspension form would achieve this target in roughly 40% [96]. Meanwhile, a recently presented abstract reported that over 90% of children aged 2–17 years old reached Cave of 500 ng/mL when administered a novel powder for oral suspension at 4.5 mg/kg/day [105], although this formulation is not yet commercially available.

Isavuconazole is the active metabolite of the prodrug isavuconazonium sulfate, a water soluble prodrug cleaved and almost entirely cleared by plasma esterases [106]. Isavuconazonium is cleared in 98–99% of adult patients within 1–2 hours after the start of intravenous administration [107, 108]. After oral administration, the prodrug is hydrolyzed in the intestinal lumen with no quantifiable concentration of the prodrug in the plasma, but a high bioavailability of isavuconazole [106]. Isavuconazole, the active moiety, has a long elimination half-life of approximately 56–130 hours once absorbed, and does not reach steady state until day 14 with once-a-day dosing [106, 108]. It is highly protein bound to albumin with a high bioavailability and undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism [108, 109]. Exposure and half-life increase significantly with mild to moderate hepatic impairment, but dosage adjustments are not recommended due to the morbidity associated with invasive fungal diseases. There are no published PK data for children as pediatric trials are ongoing as of this writing.

3.3. Pediatric Dosing

3.3.1. Fluconazole

Fluconazole demonstrates a higher clearance in children compared to adults, with a half-life of 20 hours versus 30 hours, respectively [110]. Vd is much higher in neonates than in older children or adults, which is reasonable given the hydrophilicity of fluconazole and the relative total body water of neonates compared to older populations [110]. For neonates, it is recommended to administer a 25 mg/kg loading dose followed by 12 mg/kg/day to achieve target fluconazole plasma concentrations in invasive candidiasis [110, 111]; there is no such loading dose recommendation for children outside of the neonatal period. Oropharyngeal candidiasis is treated with lower dosages: 6 mg/kg on day 1 followed by 3 mg/kg/dose once daily. Dosing is the same for IV and enteral formulations.

3.3.2. Itraconazole

The current recommendation for itraconazole dosing in children is 3–5 mg/kg/day to maintain a trough concentration of >0.5 mg/L [112]. However, studies have demonstrated that even a 5 mg/kg dose does not reliably produce goal trough concentrations in children [113]. In fact, one study suggested that a dose of 8–10 mg/kg divided over two doses reached target trough concentrations better than the recommended dose of 5 mg/kg/day [114]. Due to the high variability in absorption, and significant differences in bioavailability of oral formulations, TDM is warranted.

3.3.3. Voriconazole

As a result of differences in clearance, recommended dosages of voriconazole are roughly 2-fold higher in children than in adults. Weight-based oral dosing for children >2 years of age is 9 mg/kg twice daily (maximum of 350 mg total). Meanwhile, 8 mg/kg twice daily is utilized as maintenance dosing with the IV formulation. Population PK modeling has suggested that higher dosages (9 mg/kg TID for 3 days) may more rapidly attain therapeutic concentrations than current BID dosing without notable drug accumulation [115], but this dosage has not been fully evaluated. Similarly, optimal dosing has not been established in children <2 years of age, although limited studies suggest that higher doses may be necessary to maintain adequate trough concentrations [116]. Because parenteral voriconazole contains the excipient sulfobutyl ether β-cyclodextrin, which can accumulate in patients with renal impairment, IV voriconazole should be avoided in patients with creatinine clearance < 50 mL/minute.

3.3.4. Posaconazole

To date, posaconazole is only approved for use in children 13 years of age or older. The dosage in this age group is the same as in adults and varies by formulation. Less is known about optimal dosing in younger children. To our knowledge, there are only a few studies aimed to elucidate the PK and determine dosing of posaconazole in children under 13 years of age [96, 104, 105]. In a study by Boonsathorn et al. using TDM data collected via routine clinical care [96], modeling and simulations were performed to evaluate dosing needed to achieve targeted trough concentrations. The authors found low bioavailability of the oral suspension and recommend that children aged 6 months to 6 years receive 200 mg suspension 4 times per day, while children 7 −12 years receive 300 mg suspension 4 times per day [96]. The finding of low serum concentrations in young children treated with oral suspension is consistent with a recent study from Arrieta and colleagues, which reported that oral suspension given at 12–18 mg/kg/day in 2–3 divided doses failed to achieve target of Cave of 500–2500 ng/mL in >90% of children aged 2–17 years [104]; no specific dosing recommendations are given by these authors. Boonsathorn and colleagues also include recommendations about dosing of the delayed-release (“gastro-resistant”) tablet [96], but few PK samples (n=12) were included from subjects taking this formulation, precluding conclusions about optimal dosing of delayed-release tablets in children less than 13 years of age. Meanwhile, data from an open-label, dose-escalation trial of IV and a novel powder for oral suspension (PFS) formulations show that >90% of children 2–17 years of age achieved target Cave > 500 ng/mL at dosing of 4.5–6 mg/kg/day with both IV and PFS formulations [105].

As with adults and older children, there are significant differences in the drug concentrations achieved with the various available posaconazole formulations. As such, dosing will likely differ by formulation when this drug is approved in children under the age of 13 years. Until dosing is better determined, TDM and concentration-dependent dose adjustments may be beneficial if this drug is used in younger children. Similar to voriconazole, the IV formulation of posaconazole contains cyclodextrin, which can accumulate in patients with renal function impairment. Use of the IV formulation should be based on a careful risk/benefit assessment in patients with creatinine clearance below 50 mL/min.

3.3.5. Isavuconazole

The optimal dosage of isavuconazole in children has not been established. However, a recent conference abstract reported that a 10mg/kg IV dose (maximum 372mg) administered to children aged 1–18 years old produced similar exposures to adults [117]. In adults, dosing of the IV and enteral formulations are the same. Because its IV formulation does not contain cyclodextrin, dosages do not need to be adjusted in patients with renal impairment [118], unlike with voriconazole.

3.4. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring – adverse events

Therapeutic drug monitoring is utilized for triazole agents to optimize clinical outcomes and limit adverse effects. Although the AUC/MIC ratio is the best determinant for efficacy, AUC correlates well with trough concentrations for azoles as determined by linear regression [119], and so trough concentrations are most often used for TDM. Low variability in fluconazole PK parameters decreases the utility of TDM for this agent and, therefore, is not routine. However, van der Elst et al. reported that 40% of critically ill pediatric cancer patients exhibit subtherapeutic fluconazole Cmin concentrations (< 11 mg/L) and, therefore, TDM should be considered in this population due to the higher mortality risk for invasive fungal infections [120].

Voriconazole trough concentrations between 1–6 mg/L have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes while minimizing adverse effects [121]. Dose adjustments after TDM improves target attainment in adult patients [122], but frequent TDM may be required in children due to the higher variability in PK observed in this population [123]. Voriconazole levels should be measured every 3–5 days until appropriate concentrations are attained. Additionally, if voriconazole is administered for a prolonged period of time (i.e. >2 months), repeat drug concentrations should be obtained as autoinduction can lead to subtherapeutic concentrations over time [90, 91].

A similar practice is occurring with posaconazole due to the high variability of absorption and CL in children. Goal trough concentrations of ≥0.7 mg/L for prophylaxis and ≥1 mg/L for treatment are recommended [124, 125]. Because of the improved bioavailability of posaconazole tablets, TDM can performed after 3 days, as well as with IV formulation, while steady-state may not be achieved until >7 days with the oral suspension. The TDM targets for itraconazole for both prophylaxis and treatment are >0.5 mg/L [126], and monitoring should occur 5–7 days after initiation of therapy or with dose adjustments. The exposure-response profile has not been fully elucidated for isavuconazole, thus TDM targets have not been established.

It is noteworthy that all of the triazoles demonstrate clinically significant interactions with hepatic CYP enzymes to varying degrees, mostly as inhibitors [127]. This can result in increases in other hepatically metabolized drugs, such as immunosuppressive drugs [128]. Triazole dosages may need to be adjusted when co-administered with other CYP-inducing or -inhibiting medications, and close monitoring of serum levels is important. Isavuconazole has fewer drug-drug interactions than other azoles: in a study of adult HCT recipients, isavuconazole only modestly affected levels of tacrolimus and sirolimus [129].

Hepatotoxicity is the most notable side effect of triazole agents, although the incidence of hepatotoxicity with azoles is similar to that seen with AmB products [130]. Visual disturbance and rash/photosensitivity are unique side effects of voriconazole compared to other azoles, occurring in as many as 45% and 8% of adults, respectively [78, 131]. Furthermore, voriconazole is a known photosensitizing agent and multiple studies have demonstrated that voriconazole exposure produces a higher risk for developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas, even after adjusting for sun exposure [132–134]. Cancer risk has correlated with duration of voriconazole exposure and fairer skin [135]. A more complete list of toxicities can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Drug-drug interactions and notable toxicities for triazole agents.

| Drug-Drug Interactions | Inhibits CYP2C9, 2C19, 3A4 | Inhibits CYP2C9 & 3A4 | Inhibits CYP2C9, 2C19, 3A4 | Inhibits CYP3A4 | Inhibits CYP3A4 |

| Toxicities | Nausea, vomiting Prolonged QTc interval Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrosis Agranulocytosis |

Nausea, vomiting Hypertriglyceridemia Hypokalemia Hepatotoxicity Peripheral neuropathy |

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea Visual disturbances Hepatotoxicity Skin rash, photosensitivity Hallucinations Tachyarrhythmias Prolonged QTc interval |

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea Prolonged QTc interval |

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea Visual disturbances Hepatotoxicity Skin rash, photosensitivity |

4. ECHINOCANDINS

4.1. Spectrum of activity and clinical indications

There are two echinocandin agents currently approved for use in children in the United States and Europe: caspofungin and micafungin. Clinical use of these agents has increased substantially in recent years among hospitalized children in the United States [1]. Anidulafungin, the most recently licensed agent in this class, does not yet have a labeled pediatric indication. All three commercially available echinocandin agents exert activity by inhibiting β(1–3)-glucan synthase activity and preventing synthesis of the fungal cell wall [136, 137]. They demonstrate similar spectra and degree of activity with potent fungicidal activity against yeasts, most notably Candida species [138, 139], as well as fungistatic activity against Aspergillus species [140, 141]. They have little to no activity against Cryptococcus neoformans, Trichosporon species, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [142], nor against species in the Mucorales order [143]. Echinocandin resistance in Candida spp. results from amino acid substitutions in the FKS gene, which confers decreased affinity of glucan synthase to the drugs [144]. Fortunately, echinocandin resistance is uncommon among Candida species [144–147]: C. albicans (0.0%–0.1%), C. parapsilosis (0.0%–0.1%), C. tropicalis (0.5%–0.7%), C. krusei (0.0%–1.7%), and C. glabrata (1.7–3.5%), as reported by the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program from 1997–2006 [146].

Extensive clinical experience and durable antifungal activity has led to the adoption of echinocandins as first-line therapy for invasive candidiasis (IC) in neonates, children and adults by the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases [40] and the Infectious Diseases Society of America [12]. Although there are few pediatric trials, echinocandins have demonstrated comparable effectiveness and safety to amphotericin products for the treatment of IC in infants and children [148–150], as well as empiric treatment of febrile neutropenia in pediatric patients [151]. Most isolates of C. auris (>95%) are susceptible to echinocandins [152], and so they are considered first-line therapy for this emerging, multidrug-resistant pathogen [153], as well. Although echinocandins are active against many Aspergillus species in vitro [142], they are reserved for treatment of refractory cases or as salvage therapy [19].

4.2. Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics

Preclinical studies have determined that echinocandins exhibit time- and concentration-dependent fungal killing of Candida spp. with significant post-antifungal effects (PAFE) [154–157], meaning that fungicidal activity persists even after concentrations have declined. The PD parameter best associated with effectiveness against Candida species is the ratio between the area under the 24-hour concentration-time curve (AUC24) to the MIC ratio (AUC24/MIC) [154–156]. The specific PD targets are generally similar for the 3 agents, but vary by Candida species [156]. In an in vivo study conducted by Andes et al. [156], the PD target for C. albicans (mean fAUC24/MIC of 20.6 +/− 32) was significantly higher than for C. glabrata (mean 7.0 +/− 8.3) and C. parapsilosis (mean 7.6 +/− 7.1) for each agent. Because echinocandins are fungistatic against Aspergillus species, it is difficult to define MICs and instead a minimum effective concentration (MEC) ratio is used to define activity [158], which is the concentration at which hyphae transition to abnormal forms. No specific AUC/MEC ratio has been established as a PD target for clinical care, however.

Echinocandins are large molecules with poor bioavailability [136], and thus far are only available for parenteral administration. The pharmacologic properties of the 3 agents are similar, demonstrating linear pharmacokinetics over a range of clinically relevant dosages [159–161] and distributing well into most tissues [162]. They do not penetrate well into the eye [161, 163, 164] or CSF [161, 165], however, and distribute slowly into urine [166]. There is debate regarding the clinical significance of echinocandins’ poor urine penetration, which differs from their parenchymal penetration into kidney: preclinical studies have found that drug concentrations in kidney are comparable to those found in other organs [161, 162, 167], and that concentrations persist in kidney well after serum concentrations decline [154]. To that end, there have been numerous reports of successful treatment of Candida urinary tract infections with echinocandins [168–171]. Despite this, there are insufficient data to support recommendations for their use in the treatment of urinary tract infections [12, 19], at least as first-line therapy.

Similarly, despite poor CSF penetration, echinocandin concentrations in brain tissue exceed those in CSF [161, 172] and there are case reports of successful treatment of Candida meningitis [173, 174] and of CNS aspergillosis [175]. Preclinical studies, along with population PK analyses, support use of higher dosages of micafungin for treatment of Candida meningoencephalitis in neonates [172, 176, 177]. Based on a dose-dependent penetration into CNS and dose-microbiological response demonstrated in preclinical studies [172], a dosage of 10 mg/kg is recommended by European guidelines for treatment of hematogenous Candida meningoencephalitis in neonates [40]. However, despite the PK data, the Infectious Diseases Society of America continues to recommend echinocandins only for salvage therapy or in cases of toxicity to other agents [12]. Additionally, there are insufficient data to guide the optimal dosing of caspofungin for neonatal meningitis or for any of the echinocandins for treatment of CNS infections outside of the neonatal period.

There are significant differences in the metabolism and elimination of the three agents. Anidulafungin undergoes nonenzymatic chemical degradation [178], while micafungin and caspofungin are subject to hepatic metabolism [179, 180], albeit via different mechanisms. As a result, dosing of micafungin and caspofungin should be adjusted in patients with moderate or severe hepatic dysfunction, while anidulafungin dosing does not. None of the echinocandins undergo significant renal elimination and, thus, dosage adjustments are not needed in patients with renal impairment, including those receiving continuous venovenous hemofiltration or hemodialysis [181–183].

All three agents are highly protein bound (92–99%), predominantly to albumin [166], and have long half-lives in plasma of up to 24–72 hours with attainment of steady-state after several days [136]. Critically ill adult patients with hypoalbuminemia have higher caspofungin clearance and a resultant lower AUC0–24 [184]. This has been hypothesized to be due to the presence of extensive protein binding, in which small reductions in serum albumin lead to a larger free fraction of drug available for elimination. However, decreased protein binding may also result in increased distribution of unbound drug to tissues, improving echinocandins’ effectiveness against tissue-based infections. The impact of serum albumin on echinocandins’ distribution and clearance, and thus dosing, in infants and children is unclear.

4.3. Pediatric Dosing

4.3.1. Micafungin

Children exhibit a nonlinear, inverse relationship between weight and clearance of micafungin [185, 186]. As weight decreases, relatively larger dosages are needed to attain similar exposures to those in heavier patients. As a result, larger weight-based doses of micafungin (per kg) are needed for treatment in infants and smaller children [185]. Data support dosing of micafungin of 2–4 mg/kg once daily for treatment of candidemia in children 4 months and older [185]. Because children above 50 kg achieve similar exposures as adults when receiving a fixed dosage of 100 mg per day, adult dosing is recommended in heavier children [185]. The use of higher dosages (3–5 mg/kg) less often (every 2–3 days or twice weekly) has been evaluated as an approach to prophylaxis in children at-risk for IFD [187–189]. These regimens were found to attain PD targets against susceptible isolates in the majority of children [187–189], but have not been adopted into clinical practice. An in-depth review of intermittent dosing strategies by Lehrnbecher and colleagues has been provided elsewhere [190].

Neonates, on the other hand, require substantially larger dosages (10–15 mg/kg) in order to adequately treat disseminated candidiasis [176], because this disease often involves the CNS (i.e. meningoencephalitis) in this age group [172]. Several small, observational studies of preterm and term neonates and infants have been performed, demonstrating that dosages up to 15 mg/kg/day are well-tolerated in infants [176, 191, 192]. As a result, higher dosages (4–10 mg/kg/day) are endorsed by European guidelines for treatment of invasive candidiasis in neonates, with specific recommendations for use of 10 mg/kg/day when meningoencephalitis is suspected [40]. Despite these reports, the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends that echinocandins only be used in neonates as salvage therapy or in settings in which other agents are not tolerated [12].

4.3.2. Caspofungin

Clearance and volume of distribution of caspofungin are more closely related to body surface area (BSA) than weight alone [193–196]. Dosing scaled to BSA better approximates adult dosing than use of mg/kg dosing for this agent [194]. As a result, BSA-informed dosing of 70 mg/m2 as a loading dose followed by 50 mg/m2 for maintenance is recommended for children ≥3 months of age [193]. BSA dosing is also recommended for neonates and infants less than 3 months: dosages of 25 mg/m2 achieved similar plasma exposure to that of adults receiving standard 50 mg doses in a study of 18 neonates and young infants [197], forming the basis for dosing recommendations in this age group. Caspofungin is the only echinocandin for which dosing adjustments are recommended in patients with hepatic dysfunction. Clearance of caspofungin is not affected by mild liver dysfunction [184, 198, 199], but it is decreased in patients with moderate hepatic impairment, leading to recommendations for use of lower doses in such patients [200].

4.3.3. Anidulafungin

Although anidulafungin is not yet approved in children, PK studies have been performed in pediatric patients across a range of ages [201, 202]. Dosages of 0.75 and 1.5 mg/kg/day achieved comparable AUCs to those achieved with 50 mg and 100 mg doses in adults, respectively [201, 202]. A loading dose of twice the maintenance dose is recommended for adults on day 1 and, presumably, would be advised for children.

4.4. Therapeutic drug monitoring – adverse events

Echinocandins are generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events include infusion reactions and elevation of hepatic transaminases [195, 196, 201–203], which is most often mild. In general, TDM is not performed for echinocandins. Because of the extent of protein binding (>95%), clinical assays that reliably measure free drug concentrations would be necessary to determine the amount of active drug in plasma. TDM may be beneficial when using echinocandins for treatment of organisms with decreased susceptibility to ensure that total plasma concentrations are in line with published studies.

5. OTHER AGENTS

5.1. Flucytosine (5-FC)

Flucytosine, also known as 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC), is one of the oldest antifungal drugs. It inhibits protein and DNA synthesis following conversion from 5-FC to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) within fungal cells [204]. Human cells lack the enzyme to convert 5-FC to 5-FU, although intestinal microbes can convert the drug [205], which can lead to systemic 5-FU levels and possible toxicity. Flucytosine is active in vitro against many yeasts and some molds, but its clinical utility is largely limited to adjunctive therapy for cryptococcal meningitis [14]. Because of the rapid emergence of resistance when used as monotherapy, 5-FC is almost always administered in combination with an AmB product. Flucytosine and AmB provide additive activity against C. neoformans and C. albicans [47, 206]. As a result, co-administration can facilitate the use of lower dosages in the treatment of these organisms than are required when either agent is used alone.

Flucytosine is available in both enteral and parenteral formulations. Because it is highly bioavailable, intravenous administration is generally restricted to critically ill patients who cannot take enteral medications. The standard dosage of 5-FC is 100 mg/kg divided every 6 hours, which is recommended for both children and adults, although higher dosages are sometimes used. Neonates achieve higher serum concentrations than older children [207, 208], therefore 75 mg/kg/day is the typical dose for infants less than 30 days of age. Dose adjustments are also needed in patients with impaired renal function. The PK of 5-FC demonstrates significant inter-individual variability [209] and, because 5-FC exhibits concentration-dependent toxicity, which manifests most frequently as hepatotoxicity (elevated transaminases) and bone marrow suppression (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia) [210], TDM is paramount. Peak (1–3 hours post-dose) serum concentrations >100 mg/L are associated with toxicity [211], thus TDM should be utilized routinely in children treated with 5-FC, with peak concentrations 50–100 mg/L and trough levels 25–50 mg/L considered acceptable [204].

5.2. Terbinafine

Terbinafine is an allylamine drug with broad antifungal activity. It exerts its action by inhibiting the fungal enzyme squalene epoxidase and, ultimately, ergosterol formation [212]. Clinically, terbinafine is most often used to treat tinea capitis or onychomycosis because of excellent penetration into nail, skin, and hair follicles [213]. In clinical trials, terbinafine is noninferior to griseofulvin for treatment of tinea capitis [214]. Terbinafine is highly protein bound (>99%) and accumulates in skin and adipose tissue, leading to a terminal half-life >150 hours in plasma [215]. In addition, the penetration of terbinafine into other pertinent tissues, such as brain, is unknown. As a result, its role as monotherapy for treatment of noncutaneous infections is questionable. Terbinafine has also shown in vitro synergistic activity with azoles against several clinically relevant molds, including Aspergillus species, Fusarium species, Rhizopus species, Scedosporium species, and organisms from the Mucorales order [216]. Therefore, terbinafine may have an adjunctive clinical role in the treatment of refractory or resistant mold infections in immunocompromised children, although there are limited data documenting the clinical utility of this agent for these pathogens.

Terbinafine is FDA-approved for children 4 years and older. It is administered orally as granules (125 mg or 187.5 mg) or as a 250 mg tablet once daily. Children require larger dosages of terbinafine per kg of body weight than adults to achieve the similar systemic exposures [217]. For tinea capitis, a 6-week course of therapy with 125 mg (<25 kg), 187.5 mg (25–35 kg), or 250 mg (>35 kg) once daily is advised [217]. At dosages used for tinea capitis, terbinafine is well-tolerated with anorexia and gastrointestinal disturbance the most often reported adverse events [212, 217].

High-dose regimens (>250 mg) have been utilized in the treatment of refractory mold infections [218]. In a physiologically-based PK model [219], plasma terbinafine concentrations significantly accumulated over the first 7 days of therapy with high-dose regimens. Of the dosing regimens studied, 500 mg twice daily achieved the highest drug concentrations and PD target attainment (Cmax/MIC, AUC/MIC). However, without knowledge of the PD target associated with improved clinical outcomes in the treatment of molds, the optimal dosage for this indication is unknown.

5.3. Griseofulvin

Griseofulvin is a fungistatic antifungal with good activity against organisms that cause dermatophyte infections, such as Microsporum and Trichophyton species [220]. The drug is made soluble through its preparation as microsize and ultramicrosize particles, which increases the surface area of the drug and enhances its absorption. Its bioavailability is further enhanced by ingestion of the drug with a high fat meal or food [221]. Griseofulvin distributes well into skin, nails, hair, liver, and muscle [220], but its clinical utility is limited by its narrow spectrum of activity to the treatment of tinea infections. In a Cochrane review of therapies for tinea capitis [222], griseofulvin was found to be superior to terbinafine in the treatment of Microsporum canis infections but inferior in the treatment of Trichophyton tonsurans. Although carcinogenic in small animals [223], these same toxic effects have not been found in human studies and the drug is generally well-tolerated. It has fewer hepatotoxic effects compared to other agents used to treat dermatophyte infections including ketoconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole, and terbinafine [224].

6. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite the development of newer and safer antifungal agents, management of IFD in children is challenging. Population PK studies have been performed in infants and children, but many of these studies involve a small number of diverse pediatric subjects. Full characterization the effects of clinical factors (i.e. critical illness, obesity, organ dysfunction, age, drug interactions) on the PK of available antifungal agents in all children continues to be elucidated. Ongoing research in this area will be beneficial as the number of children at-risk for IFD expands with time. However, the low overall incidence of IFD makes performance of adequately powered trials challenging. Therefore, well-designed observational studies will continue to be needed to provide comparative effectiveness data on antifungals in children.

IFD seems like the type of infectious process for which personalized medicine would be beneficial: high mortality, limited therapeutic options, variability in drug dosage-exposure relationships. Unfortunately, TDM is not available or feasible for the majority of antifungal agents and, when performed, delayed turnaround in drug levels often impacts the clinical applicability of results. With the availability of Bayesian dose adaptation software programs and continued investigations into dose-concentration-outcome relationships, there is potential for implementation of individualized antifungal dosing to improve outcomes in IFD. But, advances in antifungal TDM are necessary to make results clinically actionable and bring the expanding amount of population PK data to the bedside.

An area not discussed in this review is the role of combination therapy in the treatment of IFD. As has been described elsewhere [178], certain antifungal combinations provide synergistic fungicidal activity in vitro. How well this translates to humans and improves outcomes of IFD is unknown. Duel therapy may be advantageous for some pathogens (i.e. more resistant organisms), infections of sites where drug delivery is impeded, such as the CNS, or in immunocompromised patients, who lack adequate immunity to clear infections once established. Translating research from the lab to the patient is particularly challenging in this area, but is an important avenue for continued investigation.

Finally, since the 1990’s, there has been a welcome expansion in the number of systemically available antifungal agents. This has included three new triazoles, three agents in the novel echinocandin class, and evolution of less toxic lipid formulations of amphotericin. Unfortunately, the immediate availability of these newer agents is often limited to adult patients as pediatric specific PK/PD data are never available at the time of initial drug approval. Clinicians caring for children at risk for or diagnosed with an IFD are placed in the precarious position of relying on older agents with known pediatric PK parameters but potentially conferring greater toxicity versus the option of extrapolating adult PK data of newer agents to off-label use in children. Fortunately, physician advocates and legislators both in the United States and in Europe recognized this delay in or absence of pediatric specific PK/PD data. In the past two decades a series of legislative acts have helped to resolve this knowledge gap; this has been described in detail in previous publications [225]. A collaborative infrastructure between pharmaceutical agencies and the FDA and EMA has improved the number of pediatric specific indications for antifungal agents. However, the time from the adult approval to pediatric approval is still ranging from 7 or 8 years. Furthermore, pediatric indications for certain antifungal agents, such as posaconazole, still remain elusive up to 13 years after the initial adult approval. Additional legislation is needed to shorten this time between adult approval and completion of pediatric specific studies.

Table 5.

Administration information and pharmacokinetic properties of echinocandin agents.

| Caspofungin | Micafungin | Anidulafungin | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available formulations | IV | IV | IV |

| Approved pediatric indications | Empirical therapy for presumed fungal infections in febrile, neutropenic patients*# Treatment of candidemia and the following Candida infections: intraabdominal abscesses, peritonitis and pleural space infections*# Treatment of esophageal candidiasis*# Treatment of invasive aspergillosis in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of other therapies*# |

Treatment of patients with candidemia, acute disseminated candidiasis, Candida peritonitis and abscesses*# Esophageal candidiasis* Prophylaxis of Candida infections in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation*# |

None |

| Pediatric dosage |

<3 months of age: 25 mg/m2 once daily [197] ≥3 months of age*: 70 mg/m2 as loading dose, max: 70 mg, followed by 50 mg/m2 once daily, max 70 mg ≥12 months of age#: 70 mg/m2 as loading dose, max: 70 mg, followed by 50 mg/m2 once daily, max 70 mg |

<4 months of age#: 4–10 mg/kg/day (invasive candidiasis); 10 mg/kg/day recommended for infants with suspected CNS infection [40] ≥4 months of age: 1 mg/kg, max: 50 mg (prophylaxis of Candida infections)*# 2 mg/kg, max: 100 mg (treatment of candidemia, disseminated candidiasis, and Candida peritonitis and abscess)*# 2.5 mg/kg, max 150 mg (treatment of esophageal candidiasis in patients >30 kg)* 3 mg/kg (treatment of esophageal candidiasis in patients ≤30 kg)* |

No labeled dosage for children 1.5 mg/kg once daily achieved similar exposures (AUC) to standard dosages (100 mg once daily) in adults [201, 202] |

| Protein binding (%) | 92–97% | >99% | 99% |

| Mean pharmacokinetic properties | |||

| Cmax(μg/dL) | 8.2 [197] <3 months of age (25 mg/m2 once daily) 15.6 −17.2 [195, 196] >3 months of age (50 mg/m2 once daily) |

16.2 [226] (1 mg/kg) 21.4 [226] (2 mg/kg) 30.4 [226] (3 mg/kg) |

4.2a [202] |

| AUC0–24(μg-h/mL) | 115–130.3 [195, 196] | 52.4 [226] (1 mg/kg) 94.3 [226] (2 mg/kg) 190.5 [226] (3 mg/kg) |

84.3b [202] |

| Half-life (h) | 7.4–11.2 [195, 196] | 11.6–13.3 [187, 226] 8.3 (premature infants [191]) | 22.9 [201] |

| Vd(L/kg) | Not reportedb | 0.28–0.35 [187, 226] 0.43 – 0.62 (premature infants [191, 192]) | 0.54 [201] |

| CLc | 5.67–8.57 [193, 195, 196] | 0.29 – 0.39 [187, 226] 0.65 (premature infants [191, 192]) | 0.015–0.02 [201, 202] |

| PK/PD target(s) | fAUC/MIC: >20 for C. albicans >7 for C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis [156] | fAUC/MIC: >20 for C. albicans >7 for C. glabrata and C parapsilosis [156] | fAUC/MIC: >20 for C. albicans >7 for C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis [156] |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | No | No | No |

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximal concentration; PK/PD, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics; Vd, volume of distribution.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration labeling

European Medicines Agency labeling

Median value reported.

Due to variable distribution, excretion and biotransformation, caspofungin does not freely equilibrate with plasma and true steady-state volume of distribution cannot be readily determined [166].

Units for CL for caspofungin: mL/min/m2; for micafungin: ml/min/kg; for anidulafungin: L/h/kg.

KEY POINTS.

While individualized dosing regimens are optimal, targeted therapy of antifungal agents in children is challenging due to the lack of known pharmacodynamic endpoints for many fungal infections and unavailability of clinical assays.

Prescribers should be attune to the data informing dosing recommendations for antifungal agents and the gaps in the current literature for children.

This review summarizes available data on the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, dosing, and therapeutic drug monitoring of available systemic antifungal agents for treatment and prevention of invasive fungal diseases in children.

Acknowledgments

Compliance with Ethical Standards: KJD is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HD091365 and has received research support from Merck & Co., Inc. and Pfizer, Inc. unrelated to the current work. BTF has received research support from Pfizer, Inc. and Merck Pharmaceuticals unrelated to the current work. BTF also serves as the Chair of a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Astellas. NRZ is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1K99HD096123. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the above supporting agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Downes KJ, Ellis D, Lavigne S, Bryan M, Zaoutis TE, Fisher BT. The use of echinocandins in hospitalized children in the United States. Med Mycol. 2018. September 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad PA, Coffin SE, Leckerman KH, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Pediatric antifungal utilization: new drugs, new trends. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008. December;27(12):1083–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lestner JM, Smith PB, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Benjamin DK Jr., Hope WW. Antifungal agents and therapy for infants and children with invasive fungal infections: a pharmacological perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013. June;75(6):1381–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andes D. Antifungal Agents Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Amphotericin B In: Nightingale CH, Ambrose PG, Drusano GL, Murakawa T, editors. Antimicrobial Pharmacodynamics in Theory and Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhary A, Prakash A, Sharma C, Kordalewska M, Kumar A, Sarma S, et al. A multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009–17) in India: role of the ERG11 and FKS1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018. April 1;73(4):891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash A, Sharma C, Singh A, Kumar Singh P, Kumar A, Hagen F, et al. Evidence of genotypic diversity among Candida auris isolates by multilocus sequence typing, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and amplified fragment length polymorphism. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2016. March;22(3):277 e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitale RG, de Hoog GS, Schwarz P, Dannaoui E, Deng S, Machouart M, et al. Antifungal susceptibility and phylogeny of opportunistic members of the order mucorales. J Clin Microbiol. 2012. January;50(1):66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman RD, Koren G. Amphotericin B nephrotoxicity in children. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2004. July;26(7):421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamill RJ. Amphotericin B formulations: a comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs. 2013. June;73(9):919–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botero Aguirre JP, Restrepo Hamid AM. Amphotericin B deoxycholate versus liposomal amphotericin B: effects on kidney function. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015. November 23(11):CD010481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blyth CC, Hale K, Palasanthiran P, O’Brien T, Bennett MH. Antifungal therapy in infants and children with proven, probable or suspected invasive fungal infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. February 17(2):CD006343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016. February 15;62(4):e1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ascher SB, Smith PB, Watt K, Benjamin DK, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Clark RH, et al. Antifungal therapy and outcomes in infants with invasive Candida infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012. May;31(5):439–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010. February 1;50(3):291–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Chakrabarti A, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2014. April;20 Suppl 3:5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, Bradsher RW, Pappas PG, Threlkeld MG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008. June 15;46(12):1801–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, Catanzaro A, Geertsma F, Hoover SE, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016. September 15;63(6):e112–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]