Abstract

The emergence of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is of global concern and might have emerged from RNA recombination among existing coronaviruses. CoV spike (S) protein which is crucial for receptor binding, membrane fusion via conformational changes, internalization of the virus, host tissue tropism and comprises crucial targets for vaccine development, remain largely uncharacterized. Therefore, the present study has been planned to determine the sequence variation, structural and antigenic divergence of S glycoprotein which may be helpful for the management of 2019-nCoV infection. The sequences of spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV and SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) were used for the comparison. The sequence variations were determined using EMBOSS Needle pairwise sequence alignment tools. The variation in glycosylation sites was predicted by NetNGlyc 1.0 and validated by N-GlyDE server. Antigenicity was predicted by NetCTL 1.2 and validated by IEDB Analysis Resource server. The structural divergence was determined by using SuperPose Version 1.0 based on cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Our data suggests that 2019-nCoV is newly spilled coronavirus into humans in China is closely related to SARS-CoV, which has only 12.8% of difference with SARS-CoV in S protein and has 83.9% similarity in minimal receptor-binding domain with SARS-CoV. Addition of a novel glycosylation sites were observed in 2019-nCoV. In addition, antigenic analysis proposes that great antigenic differences exist between both the viral strains, but some of the epitopes were found to be similar between both the S proteins. In spite of the variation in S protein amino acid composition, we found no significant difference in their structures. Collectively, for the first time our results exhibit the emergence of human 2019-nCoV is closely related to predecessor SARS-CoV and provide the evidence that 2019-nCoV uses various novel glycosylation sites as SARS-CoV and may have a potential to become pandemic owing its antigenic discrepancy. Further, demonstration of novel Cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes may impart opportunities for the development of peptide based vaccine for the prevention of 2019-nCoV.

Keywords: Coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, SARS-CoV, S glycoprotein, Glycosylation, Antigenicity, Structural divergence, COVID-19

Introduction

Coronaviruses are the large family of viruses that belongs to Coronaviridae family. On the basis of genomic structures and phylogenetic relationship, the subfamily Coronavirinae comprises of four genera Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus [1]. The transmission of alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses are limited to mammals and causes respiratory illness in humans such as SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), whereas the gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses infect birds as well as infect mammals [2]. Coronaviruses have the largest RNA genome of 26–32 kilobases (kb) with positive sense. The genome encodes four major structural proteins including spike (S), nucleocapsid (N), membrane (M) and envelope (E) which required to make complete virus particle [3]. Upon entry into host cells, the viral genome translates into two large precursor polyproteins namely as pp1a and pp1ab which get processed into 16 mature nonstructural proteins (nsp1-nsp16) by ORF 1a-encoded viral proteinases, 3C-like proteinases (3CLpro) and papain-like proteinase (PLpro). These nonstructural proteins (nsps) perform crucial function during viral RNA replication and transcription [4]. RNA recombination without proof-reading mechanism among the existing coronaviruses is mostly responsible for the evolution and emergence of novel coronaviruses [5]. The frequency of recombination has been proposed to be higher in the S gene which codes for viral spike (S) glycoprotein.

On 21st January 2020, Chinese authorities have confirmed around 200 human cases and three deaths due to the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) from Wuhan City, China. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 11th February 2020, a total of 43,103 cases have been confirmed with 1018 deaths with case fatality rate of 2.36%. Around 42,708 cases and 1017 deaths were reported from China alone. In addition to China, other South-East Asian countries including Singapore, Thailand, Republic of Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia, Vietnam, India, Philippines, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Cambodia have reported cases of 2019-nCoV. Moreover, countries like United Arab Emirates, Germany, France, United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Russia, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, USA, Canada and Australia have also reported with 2019-nCoV cases [6]. However, the route of transmission of 2019-nCoV has not been yet identified. The average age of the patients reported with 2019-nCoV infection is 56 years where more than 50% of the cases are from men. Health care professionals and hospitalized patients are at the highest risk for the 2019-nCoV transmission. Patients were mainly reported with pneumonia like symptoms as fever, fatigue, dry cough, lymphopenia, elevated level of lactate dehydrogenase and prolonged prothrombin time. In addition, patients had difficulty in breathing where chest radiographs showing bilateral patchy shadows, or ground glass opacity in all patients including invasive pneumonic infiltrates in few cases [7, 8].

The 2019-nCoV in China is suspected to emerge from closely related predecessors SARS-CoV and may spread further especially due to ongoing yearly migration and worldwide travelling. To characterize the virus and its genetic material, bronchoalveolar lavage was performed in few patients and the collected fluid samples or cultured viruses were used for next-generation sequencing. All the samples have been found to be closely related to bat SARS-like Betacoronavirus [9]. The sequenced virus “Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolates Wuhan-Hu-1” of 29,875 bp ss-RNA with the accession number of MN908947 is available on NCBI database [10]. The length of the 2019-nCoV encoded proteins were found to be almost similar among 2019-nCoV and bat SARS-like coronaviruses. However, a notable difference was found in the longer spike protein of 2019-nCoV when compared with the bat SARS-like coronaviruses and SARS-CoV [9].

The infection of coronavirus is initiated via the interaction of viral envelope with host cellular membrane [11]. The internalization of virus also depends upon the potential glycosylation sites present on viral glycoprotein. Viral envelope comprises of three proteins where spike (S) and membrane (M) are the two major glycoproteins and envelope (E) is the non-glycosylated protein. The M protein comprises of short N-terminal glycosylated ectodomain with three transmembrane domains (TM) and a long C-terminal CT domain [12]. The M and E proteins are required for virus morphogenesis, assembly and budding. S glycoprotein is a type 1 fusion viral protein that comprises of two heptad repeat regions known as HR-C and HR-N which forms the coiled-coil structures surrounded by protein ectodomain [13]. S protein cleaved into two subunits S1 and S2 where S1 comprises of minimal receptor-binding domain (270–510) that helps in receptor binding and S2 facilitates membrane fusion [14]. S protein is crucial for receptor binding, membrane fusion, internalization of the virus, tissue tropism and host range and therefore is the crucial targets for vaccine development [15]. Therefore, in the present study we analyzed the S glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV considering its importance for virus attachment to the host cell receptor and compared it with its predecessor reference SARS-CoV strain for sequence variation, glycosylation pattern, structural and antigenic divergence for a better understanding of viral pathogenesis and antigenicity.

Materials and methods

Sequences used in the study

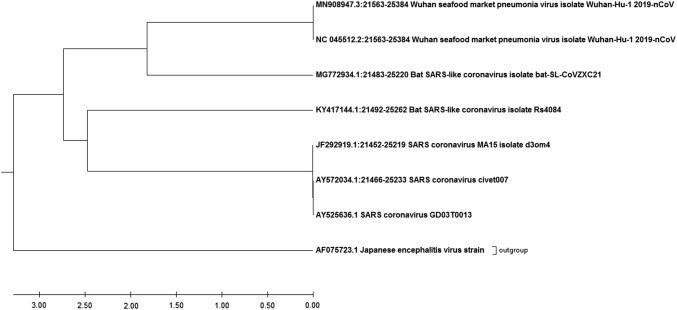

For comparison between spike gene (S) of current circulating novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and its predecessors, we have used Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolate Wuhan-Hu-1 2019-nCoV (MN908947.3), Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolate Wuhan-Hu-1 2019-nCoV (NC_045512.2), Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZXC21 (MG772934.1), Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate Rs4084 (KY417144.1), SARS coronavirus MA15 isolate d3om4 (JF292919.1), SARS coronavirus civet007 (AY572034.1) SARS coronavirus GD03T0013 (AY525636.1), where as Japanese encephalitis virus (AF075723.1) was considered as an outlier. For phylogenetic analysis, these sequences were used and tree was generated by Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis (MEGA) X software [16] and tree was generated by UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) method which is a simple agglomerative hierarchical clustering method [17].

For further comparison between S glycoprotein of current circulating 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV, we have used Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus (2019-nCoV; submitted to NCBI by Wu F et al., 17 Jan 2020) with accession number QHD43416.1 and SARS coronavirus GD03T0013 (SARS-CoV; submitted to NCBI by Song H D et al., 22 Dec 2003) with accession number AY525636.1 [18].

Variation in sequences

For analyzing the variation among the spike glycoprotein sequences, we have aligned the complete spike glycoprotein sequences of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV. Standard single-letter abbreviations for the amino acids were used. The collinear sequences were aligned by online use of Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). This data was validated further by alignment using EMBOSS Needle pairwise sequence alignment tools with EBLOSUM62 matrix, Gap penalty of 10 and extended penalty of 0.5 [19]. Mismatches and gaps were identified as (); small positive scores were identified as (.); scores > 1 were identified as (:) and identities were identified as (I). In addition, we have specifically analyzed the sequence variation in the minimal receptor-binding domain (270–510) of S glycoproteins.

Differences in glycosylation pattern

To determine the differences in the viral attachment sites of spike glycoproteins to the host cell surface, a glycosylation sites of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins were determined by NetNGlyc 1.0 software (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/) [20]. In addition, the glycosylation sites were validated by another software N-GlyDE (https://bioapp.iis.sinica.edu.tw/Nglyde/help.html) [21].

Antigenic variation

The antigenic variation among the spike glycoproteins of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV were determined using NetCTL 1.2 server (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetCTL/) [22]. The server predicts the peptide MHC class I binding; proteasomal C terminal cleavage and transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) protein transport efficiency. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes of these two spike glycoproteins were determined separately and results were compared for the epitopes with score > 0.7. The CTL epitopes were validated by another software MHC-I Binding Predictions from IEDB Analysis Resource (https://tools.iedb.org/mhci/) [23].

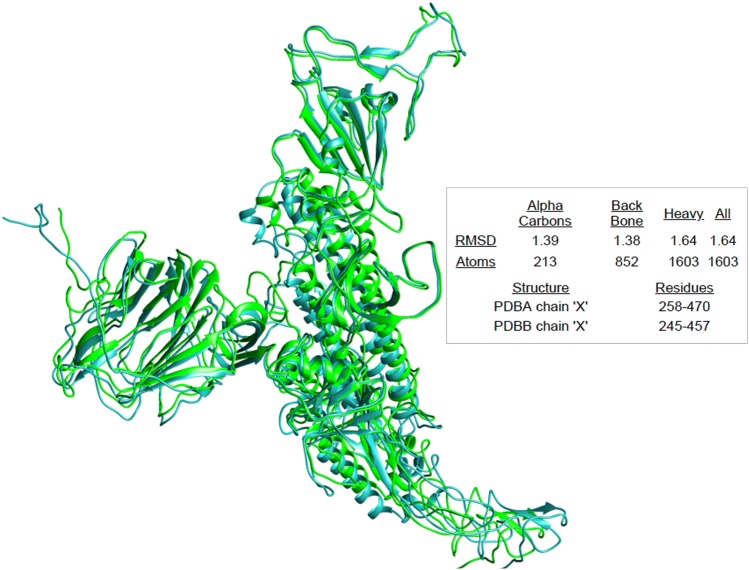

Structural divergence

To determine the structural divergence, the protein homology modeling was performed by using the spike glycoprotein sequences of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV using HHPred server (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/tools/hhpred) [24]. The generated models for S glycoproteins of 2019-nCoV (PDBA) and SARS-CoV (PDBB) were based on cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein (PDB ID 6ACC). The generated models were superimposed to determine the structural divergence using SuperPose Version 1.0 (https://wishart.biology.ualberta.ca/SuperPose/), which calculates the protein superposition using a modified quaternion approach. Deviation between the structural divergences was calculated according to the local and global RMSD values [25].

Results

Phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignment

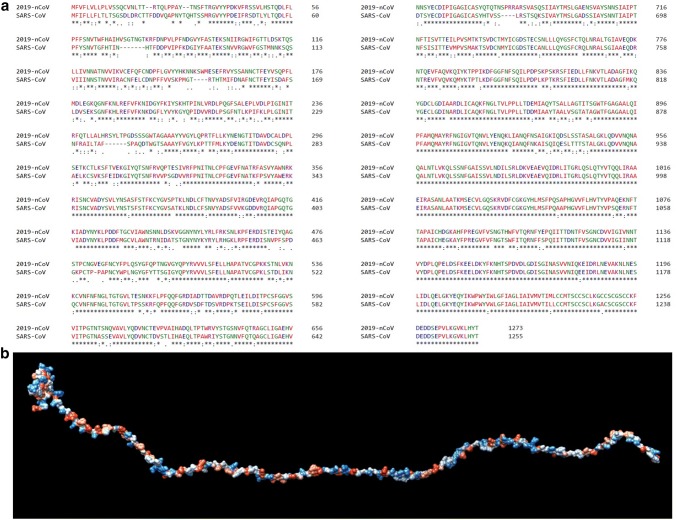

Our phylogenetic analysis exhibits that a 2019-nCoV is closely related with Bat SARS-like coronavirus. However, both 2019-nCoV and Bat SARS-like coronavirus emerged from the SARS coronavirus (Fig. 1). Suggesting that 2019-nCoV is newly spilled coronavirus into humans in China is closely related to SARS-CoV. Further, complete sequence alignment data suggested that spike glycoprotein sequences of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV exhibits 76.2% identity, 87.2% similarity and 2% Gaps (Fig. 2a). This data suggests that spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV exhibits higher sequence similarity with 12.8% of difference with SARS-CoV. Additionally, we looked into the sequence variation of minimal receptor-binding domain (RBD) from 270 to 510 amino acids which are required for its interaction with cellular receptors. We have found that spike glycoproteins exhibits 73.3% identity, 83.9% similarity and 0.4% Gaps, suggesting 16.1% difference and the tertiary structure of minimal RBD has been shown in Fig. 2b. The significant variation in minimal RBD of S-glycoprotein suggests that 2019-nCoV may have alteration in virus binding capacity and infectivity into the host cell receptor.

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny of 2019-nCoV. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by molecular evolutionary genetic analysis (MEGA) software based on the spike gene sequences, showing the evolutionary relationship of 2019-nCoV with predecessors strains of SARS-coronaviruses. The phylogenetic analysis showing that 2019-nCoV is closely related with Bat SARS-like coronavirus. However, both 2019-nCoV and Bat SARS-like coronavirus emerged from the SARS coronavirus. The accession number of the sequences used for the phylogenetic analysis is represented at the tip of the branches, where Japanese encephalitis virus has been used as the outgroup

Fig. 2.

Sequence variation of spike glycoprotein. a The complete amino acid sequences of spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV are shown as described earlier. Standard single-letter abbreviations for the amino acids were used. The collinear sequences were aligned by online use of Clustal Omega. Amino acid alignment exhibits non-conservative substitutions (“.”), conservative substitutions (“:”) and semi-conservative substitutions (“.”). Conserved regions are represented as (“”). There are 76.2% identity, 87.2% similarity and 2% Gaps in 1273 positions. b The tertiary structure of minimal RBD (residues 270–510)

Variation in glycosylation pattern of spike glycoproteins

The potential glycosylation sites among both the spike glycoproteins were compared and presented in Table 1. As compared with the SARS-CoV, we have found that spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV exhibits novel glycosylation sites such as NGTK, NFTI, NLTT, and NTSN that may be the results of sequence variation. In addition, we have also found that the 2019-nCoV spike glycoprotein exhibits common glycosylation sites that were also present in SARS-CoV such as NITN, NGTI, NITN, NFSQ, NESL, NCTF and NNTV (Table 1). Our glycosylation data suggests that the 2019-nCoV may interacts with host receptor using novel glycosylation sites that may affect the internalization process and associated pathogenesis.

Table 1.

Comparison of N-glycosylation sites between spike glycoproteins of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV strains

| N-glycosylation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-nCoV | SARS-CoV | ||||||||||

| Position (NetNGlyc 1.0) agreement result | Position (N-GlyDE) | Sites | Potential | Jury agreement | N-Glyc Result | Position (NetNGlyc 1.0) agreement result | Position (N-GlyDE) | Sites | Potential | Jury agreement | N-Glyc Result |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | 29 | 29 | NYTQ | 0.7751 | (9/9) | +++ |

| 61 | 61 | NVTW | 0.7820 | (9/9) | +++ | 65 | 65 | NVTG | 0.8091 | (9/9) | +++ |

| 234 | 234 | NITR | 0.7613 | (9/9) | +++ | 227 | 227 | NITN | 0.7518 | (9/9) | +++ |

| 74 | 74 | NGTK | 0.7192 | (9/9) | ++ | 119 | 119 | NSTN | 0.7039 | (9/9) | ++ |

| 282 | 282 | NGTI | 0.7378 | (9/9) | ++ | 269 | 269 | NGTI | 0.6910 | (9/9) | ++ |

| 616 | 616 | NCTE | 0.7163 | (9/9) | ++ | 318 | 318 | NITN | 0.6413 | (9/9) | ++ |

| 717 | 717 | NFTI | 0.6426 | (9/9) | ++ | 602 | 602 | NCTD | 0.6916 | (9/9) | ++ |

| 1194 | 1194 | NESL | 0.6791 | (9/9) | ++ | 783 | 783 | NFSQ | 0.6260 | (9/9) | ++ |

| 17 | 17 | NLTT | 0.6606 | (8/9) | + | 1176 | 1176 | NESL | 0.6794 | (9/9) | ++ |

| 122 | 122 | NATN | 0.6781 | (8/9) | + | 73 | 73 | NHTF | 0.5303 | (4/9) | + |

| 149 | 149 | NKSW | 0.6318 | (7/9) | + | 109 | 109 | NKSQ | 0.6080 | (7/9) | + |

| 165 | 165 | NCTF | 0.6220 | (8/9) | + | 158 | 158 | NCTF | 0.5808 | (7/9) | + |

| 331 | 331 | NITN | 0.5970 | (7/9) | + | 330 | 330 | NATK | 0.6063 | (8/9) | + |

| 343 | 343 | NATR | 0.5671 | (8/9) | + | 357 | 357 | NSTS | 0.6836 | (8/9) | + |

| 603 | 603 | NTSN | 0.5783 | (6/9) | + | 589 | 589 | NASS | 0.5777 | (6/9) | + |

| 801 | 801 | NFSQ | 0.6146 | (8/9) | + | 699 | 699 | NFSI | 0.5356 | (7/9) | + |

| 1098 | 1098 | NGTH | 0.5496 | (5/9) | + | 1080 | 1080 | NGTS | 0.5806 | (7/9) | + |

| 1134 | 1134 | NNTV | 0.5800 | (6/9) | + | 1116 | 1116 | NNTV | 0.5107 | (5/9) | + |

The table shows a comparison of predicted N-glycosylation sites in Spike glycoprotein of Wuhan-Hu-1–2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and SARS coronavirus-2003 (SARS-CoV) strains. N-glycosylation potential (0.5) was taken as cutoff. The N-glycosylation sites were determined by NetNGlyc 1.0 [20] and validated by N-GlyDE server [21]

*Italics indicates the differences between N-glycosylation sites between the two Spike glycoproteins

Antigenic variation in spike glycoproteins

The antigenic variation in both spike glycoproteins of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV were compared to determine the antigenicity. We have found that most of the CTL epitopes are novel from the SARS-CoV. However, six epitopes RISNCVADY, CVADYSVLY, RSFIEDLLF, RVDFCGKGY, MTSCCSCLK and VLKGVKLHY were found to be identical (represented in italics) in both the spike glycoproteins (Table 2). In addition, some of the epitopes were identified with change in single amino acid (represented in italics*). The antigenicity data suggested that the 2019-nCoV exhibits few antigenic similarities with SARS coronavirus that might be associated with the similar antigenic response and therefore can be considered as the one of preventive strategies based on S glycoprotein peptide based vaccine designed for SARS-CoV. In addition, the novel epitopes may be used to design newer effective vaccines.

Table 2.

Comparison of antigenicity between spike glycoproteins of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV strains

| Antigenicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-nCoV | SARS-CoV | ||||

| Peptides (IEDB) | Peptides (NetCTL 1.2) | Position (start) | Peptides (IEDB) | Peptides (NetCTL 1.2) | Position (start) |

| NSFTRGVYY | NSFTRGVYY | 30 | FDDVQAPNY | FDDVQAPNY | 22 |

| STQDLFLPF | STQDLFLPF | 50 | HTSSMRGVY | HTSSMRGVY | 33 |

| VLPFNDGVY | VLPFNDGVY | 83 | TSSMRGVYY | TSSMRGVYY | 34 |

| CNDPFLGVY | CNDPFLGVY | 136 | EIFRSDTLY | EIFRSDTLY | 45 |

| WMESEFRVY | WMESEFRVY | 152 | RSDTLYLTQ | RSDTLYLTQ | 48 |

| YSSANNCTF | YSSANNCTF | 160 | LTQDLFLPF | LTQDLFLPF | 54 |

| SANNCTFEY | SANNCTFEY | 162 | TQDLFLPFY | TQDLFLPFY | 55 |

| FVFKNIDGY | FVFKNIDGY | 192 | VIPFKDGIY | VIPFKDGIY | 80 |

| NIDGYFKIY | NIDGYFKIY | 196 | HTMIFDNAF | HTMIFDNAF | 149 |

| WTAGAAAYY | WTAGAAAYY | 258 | NAFNCTFEY | NAFNCTFEY | 155 |

| GAAAYYVGY | GAAAYYVGY | 261 | ISDAFSLDV | ISDAFSLDV | 164 |

| ITDAVDCAL | ITDAVDCAL | 285 | FKNKDGFLY | FKNKDGFLY | 187 |

| LSETKCTLK | LSETKCTLK | 296 | NKDGFLYVY | NKDGFLYVY | 189 |

| NATRFASVY | NATRFASVY | 343 | GTSAAAYFV | GTSAAAYFV | 246 |

| RISNCVADY | RISNCVADY | 357 | SAAAYFVGY | SAAAYFVGY | 248 |

| CVADYSVLY | CVADYSVLY | 361 | NATKFPSVY | NATKFPSVY | 330 |

| NSASFSTFK | NSASFSTFK | 370 | RISNCVADY | RISNCVADY | 344 |

| ASFSTFKCY | ASFSTFKCY | 372 | CVADYSVLY | CVADYSVLY | 348 |

| FTNVYADSF | FTNVYADSF | 392 | TSFSTFKCY | TSFSTFKCY | 359 |

| VGGNYNYLY | VGGNYNYLY | 445 | FSNVYADSF | FSNVYADSF | 379 |

| ERDISTEIY | ERDISTEIY | 465 | ATSTGNYNY | ATSTGNYNY | 430 |

| TSNQVAVLY | TSNQVAVLY | 604 | STGNYNYKY | STGNYNYKY | 432 |

| YQDVNCTEV | YQDVNCTEV | 612 | CTPPAPNCY | CTPPAPNCY | 467 |

| QLTPTWRVY | QLTPTWRVY | 628 | FYTTSGIGY | FYTTSGIGY | 483 |

| AEHVNNSY | AEHVNNSY | 653 | TSGIGYQPY | TSGIGYQPY | 486 |

| VASQSIIAY | VASQSIIAY | 687 | FTDSVRDPK | FTDSVRDPK | 558 |

| KTSVDCTMY* | KTSVDCTMY* | 733 | ASSEVAVLY | ASSEVAVLY | 590 |

| STECSNLLL* | STECSNLLL* | 746 | SSEVAVLYQ | SSEVAVLYQ | 591 |

| ECSNLLLQY* | ECSNLLLQY* | 748 | CTDVSTLIH | CTDVSTLIH | 603 |

| RSFIEDLLF | RSFIEDLLF | 815 | QLTPAWRIY | QLTPAWRIY | 614 |

| LTDEMIAQY* | LTDEMIAQY* | 865 | GAEHVDTSY | GAEHVDTSY | 638 |

| GTITSGWTF | GTITSGWTF | 880 | TSQKSIVAY | TSQKSIVAY | 669 |

| RVDFCGKGY | RVDFCGKGY | 1039 | LGADSSIAY | LGADSSIAY | 681 |

| FVSNGTHWF | FVSNGTHWF | 1095 | KTSVDCNMY* | KTSVDCNMY* | 715 |

| VSNGTHWFV | VSNGTHWFV | 1096 | STECANLLL* | STECANLLL* | 728 |

| MTSCCSCLK | MTSCCSCLK | 1237 | ECANLLLQY* | ECANLLLQY* | 730 |

| VLKGVKLHY | VLKGVKLHY | 1264 | RSFIEDLLF | RSFIEDLLF | 797 |

| – | – | – | LTDDMIAAY* | LTDDMIAAY* | 847 |

| – | – | – | GTATAGWTF | GTATAGWTF | 862 |

| – | – | – | TTSTALGKL | TTSTALGKL | 922 |

| – | – | – | RVDFCGKGY | RVDFCGKGY | 1021 |

| – | – | – | MTSCCSCLK | MTSCCSCLK | 1219 |

| – | – | – | VLKGVKLHY | VLKGVKLHY | 1246 |

The table shows a comparison of predicted CTL epitopes in Spike glycoprotein of Wuhan-Hu-1-2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and SARS coronavirus-2003(SARS-CoV) strains. Epitopes were generated by NetCTL 1.2 [22] and validated by IEDB Analysis Resource server [23] where scores > 1.25 shows highest sensitivity and specificity towards MHC class I. Italics indicates the identical CTL epitopes

*Italics showing common epitopes with one amino acid change between the two spike glycoproteins

Structural divergence in spike glycoproteins

The overall difference of 12.8% in S glycoprotein sequences and 23.6% difference in the minimal receptor-binding domain influenced us to look for the structural divergence in spike glycoproteins of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV. The generated models were compared for the structural divergence. We have found that two glycoproteins exhibits 1.38 local RMSD value in Angstrom (Fig. 3) which showed that in spite of 12.8% variation in the sequences there was an insignificant structural divergence among the spike glycoproteins. This results suggests that the attachment inhibitors designed for SARS-CoV may be used as the current choice of therapy for 2019-nCoV.

Fig. 3.

Structural divergence of spike glycoprotein. The PDB structures of spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV (PDBA) and SARS-CoV (PDBB) were based on cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein (PDB ID 6ACC). Models were superimposed using SuperPose which was visualized by Chimera where green color showing the S glycoprotein of SARS coronavirus and cyan color represents the S glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV. The analysis suggests that both the structures exhibits insignificant divergence with 1.39 A° deviation

Discussion

The outbreak of 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China has raised alarm due to its associated global risk. The management of 2019-nCoV human infections depends on characteristics of the virus, including the transmission capability, the severity of resulting infection, and availability of vaccines or medicines to control the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Coronaviruses are zoonotic in nature that means they transmit from animals to humans [26]. However, the exact source of 2019-nCoV has not been yet identified. The evolution of 2019-nCoV may be the result of RNA recombination among the viruses as previously reported in the case of SZ3 strain of SARS-CoV which arose from the recombination of existing Rf4092 and WIV16 bat strains. Likewise, the WIV16 bat strains generated likely from the two other prevalent bat SARS-CoV strains [27]. The most frequent breakpoint for recombination exist in the S gene of coronavirus that encodes for spike (S) protein which comprises of minimal-binding domain and orf8 upstream that encodes an accessory protein [28]. Considering the prevalence and large genetic diversity of existing coronaviruses, their close proximity and frequent recombination has expected the emergence of novel variants. Our phylogenetic analysis revealed that a 2019-nCoV arises from the predecessors strains of SARS-coronaviruses.

In the present study, we have shown the sequence divergence, differences and similarity in the glycosylation sites and antigenic variation in spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV and compared with the SARS-CoV strain. Our amino acid sequence alignment data suggests a significant variation of 12.8%. In addition, we have found 23.6% difference in minimal receptor-binding domain of S glycoprotein. The significant variation in minimal receptor-binding domain of S-glycoprotein suggests that 2019-nCoV may have alteration in virus binding capacity and infectivity into the host cell receptor [29].

We have found novel glycosylation sites in the spike glycoprotein of 2019-nCoV suggesting that virus may utilize different glycosylation to interact with its receptors. We have also found that the glycosylation sites in minimal receptor-binding domain exhibits similar sites to other coronaviruses [30]. While comparing the antigenic sites, we have found that 2019-nCoV exhibits novel CTL epitopes that may results in distinct antigenic response as compared to SARS coronavirus. These novel CTL epitopes may impart opportunities for the development of peptide based vaccine for the prevention of 2019-nCoV. However, some of the epitopes were found to be similar in both the glycoproteins, suggesting that SARS-associated peptide based vaccine might be used for the prevention of 2019-nCoV in the current scenario. In this regard we have found one of the CTL epitope RVDFCGKGY has been used to design peptide based vaccine for SARS-CoV and was found to be effective in various animal models [31]. Furthermore, we have found insignificant structural divergence between two glycoproteins which suggests that the attachment inhibitors designed for SARS-CoV may be used as the current choice of therapy for 2019-nCoV.

Variation in amino acid sequences and distinctive antigenicity of 2019-nCoV suggests that although the current virus infection is not severe, it has a potential to become pandemic. Moreover, we identified an insignificant structural divergence in the spike glycoproteins that suggests that although the virus has changed its sequence its structure remains the same. The data also suggests the scope of coronavirus specific attachment inhibitors as the choice of therapy in the current pandemic situation.

Conclusions

Collectively, for the first time our results exhibit the emergence of human 2019-nCoV is closely related to predecessor SARS-CoV. Consequently, it should be renamed as SARS-CoV-2 and owing it's pandemic potential it should be declared as a public health emergency of international concern at the earliest. Foremost our data provide the evidence that 2019-nCoV uses various novel glycosylation sites as SARS-CoV and may have a potential to become pandemic owing its antigenic discrepancy. Further, demonstration of novel CTL epitopes may impart opportunities for the development of peptide based vaccine for the prevention of 2019-nCoV. Additionally our revelation of similar antigenic sites in both 2019-nCoV and SARS coronavirus, suggests the scope of SARS-associated peptide based vaccine for the prevention of 2019-nCoV. The similarity in the spike glycoprotein structures suggests the use of coronavirus specific attachment inhibitors as the current choice of therapy for 2019-nCoV.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Vice Chancellor, King George’s Medical University (KGMU), Lucknow, India for the encouragement for this work. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Funding

None.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Swatantra Kumar and Shailendra K. Saxena have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic Coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forni D, Cagliani R, Clerici M, Sironi M. Molecular evolution of human Coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25(1):35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narayanan K, Ramirez SI, Lokugamage KG, Makino S. Coronavirus nonstructural protein 1: common and distinct functions in the regulation of host and viral gene expression. Virus Res. 2015;202:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji W, Wang W, Zhao X, Zai J, Li X. Homologous recombination within the spike glycoprotein of the newly identified Coronavirus may boost cross-species transmission from snake to human. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report—22. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200211-sitrep-22-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=fb6d49b1_2. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

- 7.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen Y M, Wang W, Hu Y, et al. A novel Coronavirus associated with a respiratory disease in Wuhan of Hubei province, China. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_045512.2. Accessed 23 Jan 2020.

- 11.Schoeman D, Fielding BC. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J. 2019;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ujike M, Taguchi F. Incorporation of spike and membrane glycoproteins into coronavirus virions. Viruses. 2015;7(4):1700–1725. doi: 10.3390/v7041700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tripet B, Howard MW, Jobling M, Holmes RK, Holmes KV, Hodges RS. Structural characterization of the SARS-coronavirus spike S fusion protein core. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(20):20836–20849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babcock GJ, Esshaki DJ, Thomas WD, Jr, Ambrosino DM. Amino acids 270 to 510 of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein are required for interaction with receptor. J Virol. 2004;78(9):4552–4560. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4552-4560.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song W, Gui M, Wang X, Xiang Y. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14(8):e1007236. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall BG, Barlow M. Phylogenetic analysis as a tool in molecular epidemiology of infectious diseases. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(3):157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song HD, Tu CC, Zhang GW, Wang SY, Zheng K, Lei LC, et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(7):2430–2435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409608102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madeira F, Park YM, Lee J, Buso N, Gur T, Madhusoodanan N, et al. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W636–W641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta R, Jung E, Brunak S. Prediction of N-glycosylation sites in human proteins; 2004. https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/.

- 21.Pitti T, Chen CT, Lin HN, Choong WK, Hsu WL, Sung TY. N-GlyDE: a two-stage N-linked glycosylation site prediction incorporating gapped dipeptides and pattern-based encoding. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15975. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52341-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M. Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y, Ponomarenko J, Zhu Z, Tamang D, Wang P, Greenbaum J, et al. Immune epitope database analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W525–W530. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Söding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W244–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maiti R, Van Domselaar GH, Zhang H, Wishart DS. SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W590–594. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee A, Kulcsar K, Misra V, Frieman M, Mossman K. Bats and coronaviruses. Viruses. 2019;11(1):41. doi: 10.3390/v11010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu B, Zeng LP, Yang XL, Ge XY, Zhang W, Li B, Xie JZ, Shen XR, Zhang YZ, Wang N, Luo DS, Zheng XS, Wang MN, Daszak P, Wang LF, Cui J, Shi ZL. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related Coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS Coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(11):e1006698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham RL, Baric RS. Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. J Virol. 2010;84(7):3134–3146. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oostra M, de Haan CA, Rottier PJ. The 29-nucleotide deletion present in human but not in animal severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronaviruses disrupts the functional expression of open reading frame 8. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13876–13888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01631-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsons LM, Bouwman KM, Azurmendi H, de Vries RP, Cipollo JF, Verheije MH. Glycosylation of the viral attachment protein of avian Coronavirus is essential for host cell and receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(19):7797–7809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choy WY, Lin SG, Chan PK, Tam JS, Lo YM, Chu IM, et al. Synthetic peptide studies on the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus spike glycoprotein: perspective for SARS vaccine development. Clin Chem. 2004;50(6):1036–1042. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.029801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]