Abstract

Amyloid β (Aβ) oligomers may be a real culprit in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD); therefore, the elimination of these toxic oligomers may be of great significance for AD therapy. Autophagy is the catabolic process by which lysosomes degrade cytosolic components, and heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein (Hsc70) binds to proteins with their KFERQ-like motifs [also known as chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) motifs] and carries them to lysosomes through CMA or late endosomes through endosomal microautophagy (eMI) for degradation. In this study, our strategy is to make the pathological Aβ become one selective and suitable substrate for CMA and eMI (termed as Hsc70-based autophagy) by tagging its oligomers with multiple CMA motifs. First, we design and synthesize Aβ oligomer binding peptides with three CMA motifs. Second, we determine that the peptide can help Aβ oligomers enter endosomes and lysosomes, which can be further enhanced by ketone. More importantly, we find that the peptide can dramatically reduce Aβ oligomers in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) cortical neurons derived from AD patient fibroblasts and protect primary cultured cortical neurons against the Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity. In conclusion, we demonstrate that the peptide targeting Hsc70-based autophagy can effectively eliminate Aβ oligomers and have superior neuroprotective activity.

Keywords: Aβ oligomers, Alzheimer’s disease, Chaperone-mediated autophagy, Hsc70

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, is a devastating disease impacting more than 50 million people [1]. No effective medications can prevent or treat this disease, in part because the mechanisms underlying the AD pathogenesis and etiology are not fully understood [2]. Among all AD-associated hypotheses, the amyloid cascade hypothesis is one leading and prevailing theory to interpret AD from its initiation to progressive memory loss and frank dementia [3]. The original amyloid cascade hypothesis does not fully explain many aspects of AD pathology and symptoms; for example, relatively weak correlations between fibrillar plaque density and severity of dementia are found in AD patients [4]. The core of the updated hypothesis is that Aβ oligomers are the essential molecular entities of dementia by causing synapse and neuron loss [5]. Most of the proposed mechanisms driving the complex phenotype of AD, such as cholinergic dysfunction, inflammation, excitotoxicity, reactive oxygen species, and ApoE4, are associated with Aβ oligomers [6,7]. More importantly, the elimination of Aβ oligomers can reverse pathological and behavioral changes in several animal models of AD [8,9]; therefore, strategies to enhance the removal of these toxic oligomers may be of great significance for the AD therapy.

Autophagy, the catabolic process by which lysosomes degrade cytosolic components, has the three subtypes: macroautophagy (MA), microautophagy (MI), and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) [10]. CMA, a unique kind of selective autophagy in lysosomes, maintains cellular homeostasis by performing catabolic lysis of excess or unnecessary soluble cytosolic proteins and can be activated in response to a variety of stress conditions to restore cellular homeostasis [10]. Hsc70 recognizes CMA substrates that contain a consensus motif related to KFERQ. Once Hsc70 binds the substrate, it docks on the lysosomal membrane via a receptor known as the lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP2A). The substrate then is unfolded and translocated into the lumen for degradation [11]. Notably, Hsc70 also can serve as a chaperone for endosomal microautophagy (eMI), where Hsc70 still binds the KFERQ-like motif in a substrate protein and then interacts directly with phosphatidylserine (PS) moieties of the endosomal membrane and is internalized along with the substrate in an ESCRT-dependent manner [12]. Therefore, we term CMA and eMI as “Hsc70-based autophagy”. Hsc70-based autophagy is vital for cells since it can potentially control the homeostasis of nearly 40% of cytosolic proteins [12]. Being different from CMA, eMI may degrade oligomerized or aggregated proteins because unfolding is not necessary for the transportation of endosomal membranes [12].

CMA has been linked to several proteins known to be involved in AD pathogenesis. CMA appears to modulate amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing, tau metabolism, and calcineurin 1 (a protein overexpressed in AD) regulation [11]. Although APP contains several KFERQ motifs, it is not a suitable substrate for CMA, and Aβ is not a suitable substrate for CMA, either [13]. Based on the CMA process, two groups have established a peptide targeting a specific protein with one or several CMA motifs by non-covalent interaction between the peptide and the targeted protein for degradation through CMA [14,15]. In this study, we employ several interacting ideas to target and eliminate Aβ oligomers through the Hsc70-based autophagy directly.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Peptides and their preparations

All highly purified peptides were synthesized from Peptide 2 (Chantilly, VA). Amyloid oligomers and fibers were prepared following our previously published methods with a little modification [16]. Aβ42 was dissolved to 1 mM in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP); HFIP was evaporated, and the dry peptide was resuspended in DMSO to 5 mM. To get Aβ oligomers, the peptide was dissolved in F12 media to a final concentration of 100 μM and incubated at 4 °C for 24 h. To get Aβ fibers, the peptide was dissolved in 10 mM HCl to a final concentration of 100 μM and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C.

2.2. iPSC neuron and primary cultured cortical neuron cultures

Human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs; passage ≤35) were derived from three AD and three non-AD fibroblasts and cultured as previously described [17]. Using our established protocol, we effectively differentiated hiPSCs into forebrain-specific neural progenitors (hNPCs) and further differentiated these hNPCs into MAP2 positive neurons and then cultured them in various plates at the indicated periods. Culture of primary cortical neurons from Long Evans rats at embryonic day 18 was carried out as described previously [16,18]. Briefly, cortical neurons were digested with trypsin and plated on poly-l-lysine-coated plates with neurobasal medium containing 2% B27 and 0.5 mM glutamine. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University.

2.3. Isolation of late endosomes and lysosomes

Late endosomes and lysosomes were isolated using centrifugation in Percoll gradients and highly purified lysosomes were purified as previously described [19]. Briefly, 19% Optiprep fraction was loaded on the iodixanol gradient and ultracentrifuged at 150,000 × g for 4 h. The intactness of the lysosomes was evaluated by Neutral Red reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

2.4. Lysosome binding and uptake assays

Freshly isolated late endosomes and lysosomes or purified lysosomes were co-incubated with in vitro Aβ oligomers in modified MOPS buffer (with an additional 10 mM ATP and 5 μg/ml Hsc70 peptide) for 20 min at 37 °C. In uptake assay, treatment with proteinase K in MOPS buffer after incubation was necessary [19]. Lysosome pellets were subjected to Dot blot or Western blot after washed four times with cold PBS and centrifuged at 21,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C.

2.5. ELISA for Aβ42

After incubation with peptides or vehicle for 48 h, conditioned media were collected and used for measurement of secreted Aβ42 with Human Aβ42 ELISA Kit (Cat. No. KHB3441; Invitrogen) following the procedure provided by the manufacturer.

2.6. WST-1 assay

Primary cultured cortical neurons were plated in 96- well plates at the density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well and cultured for 12 days, then treated with Aβ oligomers in presence of various concentrations of P3 and AIP for 48 h. Cortical neurons with indicated treatments were incubated with 10 μl of WST-1 solution for 2 h in 96 well plates. The cell viability was measured at 450 nm and 600 nm in a microplate reader.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were shown as means ± SEM, and comparisons were made by unpaired two-tailed t-test for two groups and the one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-doc analysis for multiple groups. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Design specific HSC70-based autophagy peptides for Aβ oligomers

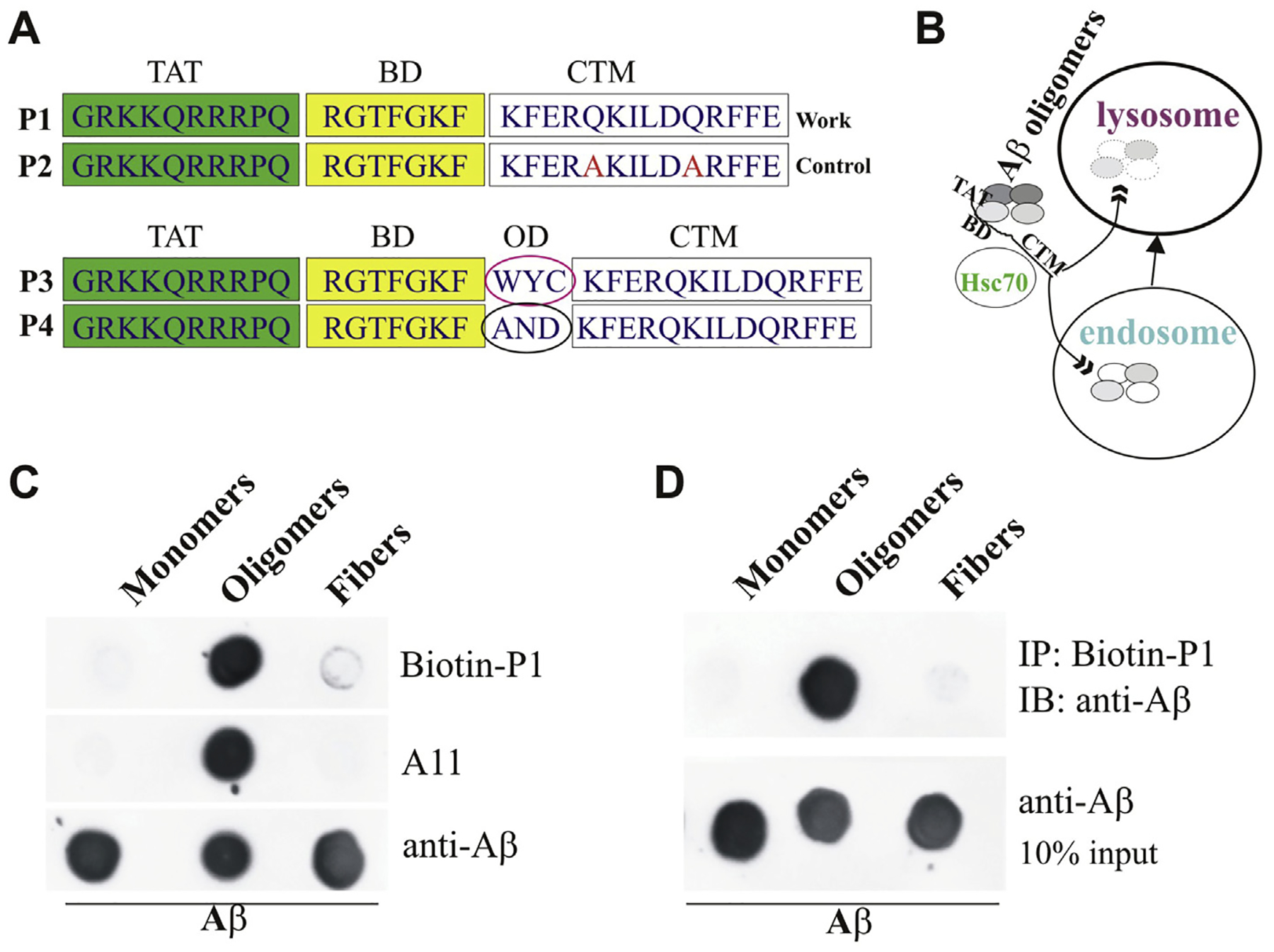

The adaptor peptide-based CMA strategy has been used to knock down α-synuclein or other several proteins successfully [14,15]. Hsc70-based autophagy is a type of autophagy that is specific for proteins containing the CMA-targeting motif (CTM). Previous studies with KFERQ-containing fusion proteins demonstrated that the attachment of CTMs is necessary to make non-CMA substrates amenable to CMA [14]. Thus, to utilize Hsc70-based autophagy as our degradation pathway to eliminate Aβ oligomers, we designed a targeting peptide consisting of three domains: a cell membrane–penetrating domain that allows the peptide to bypass the plasma membrane following peripheral delivery and the blood-brain barrier, an oligomer-binding domain that specifically binds to Aβ oligomers, and the three-CTM domain that targets the peptide-oligomer pair for degradation through the Hsc70-based autophagy proteolytic machinery. In this study, we chose the TAT amino acid sequence as the cell membrane-penetrating domain [14], an Aβ oligomer-interacting peptide sequence (RGTFEGKF, AIP) from the literature [20] as the oligomer-binding domain, and the three CTMs from RNase A, Hsc70, and hemoglobin [20], and the above peptide with mutant CTMs was synthesized as the corresponding control (Top panel, Fig. 1A). Hsc70 prefers to bind the oxidized CMA substrate proteins, which promotes the degradation of these proteins through the CMA pathway [11]. Based on this, we add three readily oxidized amino acids Tryptophan (W), Tyrosine (Y), and Cysteine (C) into the above targeting peptide sequences, while three hard oxidized amino acids Alanine (A), Asparagine (N), and Aspartic acid (D) were inserted into the corresponding peptide as control [21] (Bottom panel, Fig. 1A). We abbreviated these peptides as P1 to P4 from the top to bottom of Fig. 1A. AD-associated factors cause much oxidative stress. We predicted that the AD environment would oxidize the peptides with the three readily oxidized amino acids and that Hsc70 will more readily recognize their targeted oligomers for degradation. We proposed that the novel peptides would bring Aβ oligomers into endosomes and lysosomes for degradation (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Interacting peptide sequence to Aβ oligomers and proposed its mechanisms of action.

A. Three domains of the peptides: TAT, BD (Binding domain), and CTM (Top panel). The peptides with three readily or hard oxidized amino acids (OD, oxidized domain) (Bottom panel). B. Proposed mechanism of action of novel peptides: the novel peptides bind to Aβ oligomers, the peptide-oligomer complexes may be recognized by Hsc70, and Hsc70 brings Aβ oligomers into endosomes and lysosomes in cells for degradation. C. Determination of novel peptide with different formats of Ab: 0.5 μg of soluble Aβ42 monomers, oligomers, and fibrils was applied to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with biotin-P1, anti-oligomer A11 (AHB0052, Invitrogen), and anti-Aβ antibody (Cat. 8243, Cell signaling). D. Novel peptide specifically pulls down Aβ42 oligomers: 5 μg of soluble Aβ42 monomers, oligomers, and fibrils were incubated with Biotin-P1 for 30 min and then pulled down with the Streptavidin magnetic beads. The pellets were for dot assay probed with the anti-Aβ antibody.

Before testing the hypothesis, we identified the specificity and affinity of our novel peptides. First, we used biotinylated peptide P1 for the dot blot assay. P1 can recognize oligomers but not monomers and fibers of Aβ (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, because biotin binds to streptavidin, the biotinylated peptide P1 can be used to determine their binding oligomers using streptavidin beads. Therefore, we incubated the biotinylated P1 with Pierce™ Streptavidin Magnetic Beads. Using the streptavidin bead-biotin-P1 complexes, we pulled monomers, oligomers, and fibers of Aβ and recognized them using one general Aβ antibody. We confirmed that P1 binds explicitly to Aβ oligomers (Fig. 1D).

3.2. Novel peptides promote Aβ oligomers into endosomes and lysosomes

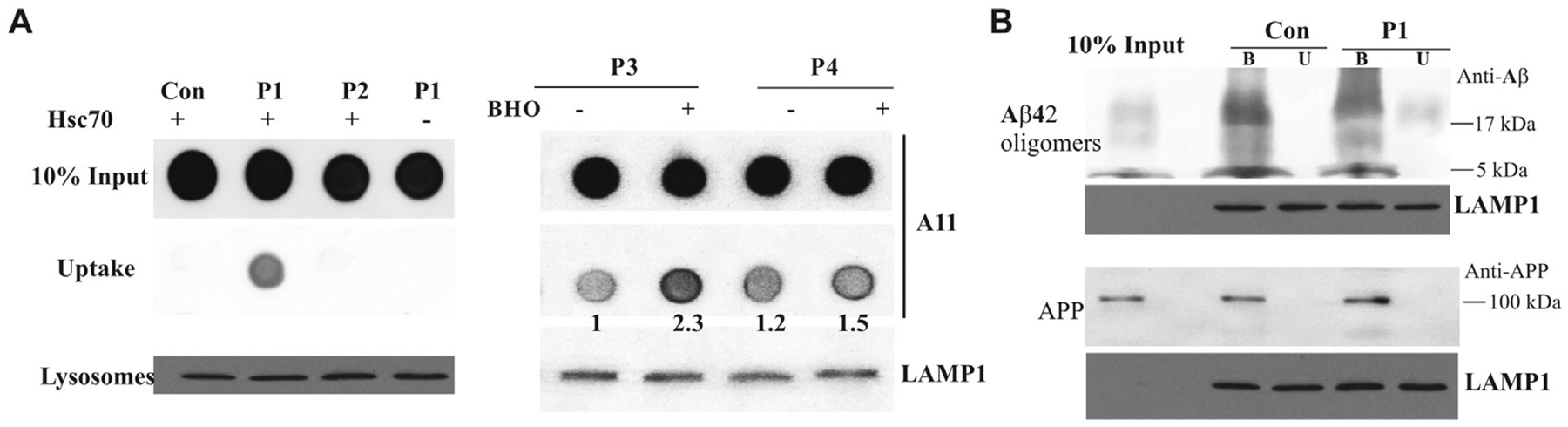

To evaluate the process of Hsc70-based autophagy, we isolated the mixture of late endosomes and lysosomes according to accepted methods [19,22], we prepared the mixture of late endosomes and lysosomes isolated from HEK293 cells for the uptake assay for Hsc70-based autophagy. We hypothesized that our novel peptides make Aβ oligomers from non-suitable to suitable substrates by tagging three Hsc70-recognized motifs. We first tested the effects of P1 and P2 on the uptake of Aβ oligomers. P1, but not P2, brought Aβ oligomers into endosomes/lysosomes in an Hsc70-dependent manner (Left panel, Fig. 2A). Oxidative stress can induce the constitutive activation of CMA, and oxidized CMA substrates are more efficiently internalized into lysosomes [11]. Interestingly, ketones can increase the CMA substrate rate of proteolysis through inducing moderate oxidation of substrates. Ketone bodies consist of three compounds: β-hydroxybutyrate (BHO), acetoacetate, and acetone [23]. We used BHO to treat P3 and P4 for 30 min and then used them for the uptake analysis. We found that BHO further increased P3, but not P4, mediating the uptake of Aβ oligomers, indicating that such a modification further promotes the uptake of Aβ oligomers into endosomes/lysosomes (Right panel, Fig. 2A). For the selectivity assay, we found that P1 can only bring Aβ oligomers but not its monomer or APP into highly purified lysosomes (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Peptides P1 and P3 bring Aβ oligomers into endosomes/lysosomes.

A. Aβ oligomers were prepared for the uptake assay and incubated with indicated novel peptides with/out Hsc70. The matrix of endosomes/lysosomes was collected for the dot blot assay with the antibody A11 (Left panel). Aβ oligomers were prepared for uptake assay and incubated with indicated novel peptides with/out BHO. The matrix of endosomes/lysosomes was collected for the dot blot assay with the antibody A11 (Right panel). B. Aβ oligomers and APP were prepared for purified lysosome binding and uptake assays with/out P1, and then collected for Western blot assay with anti-Aβ and Anti-APP antibodies. The letters B and U stand for binding and uptake assay, respectively. LAMP1 serves as controls for all uptake and binding assays.

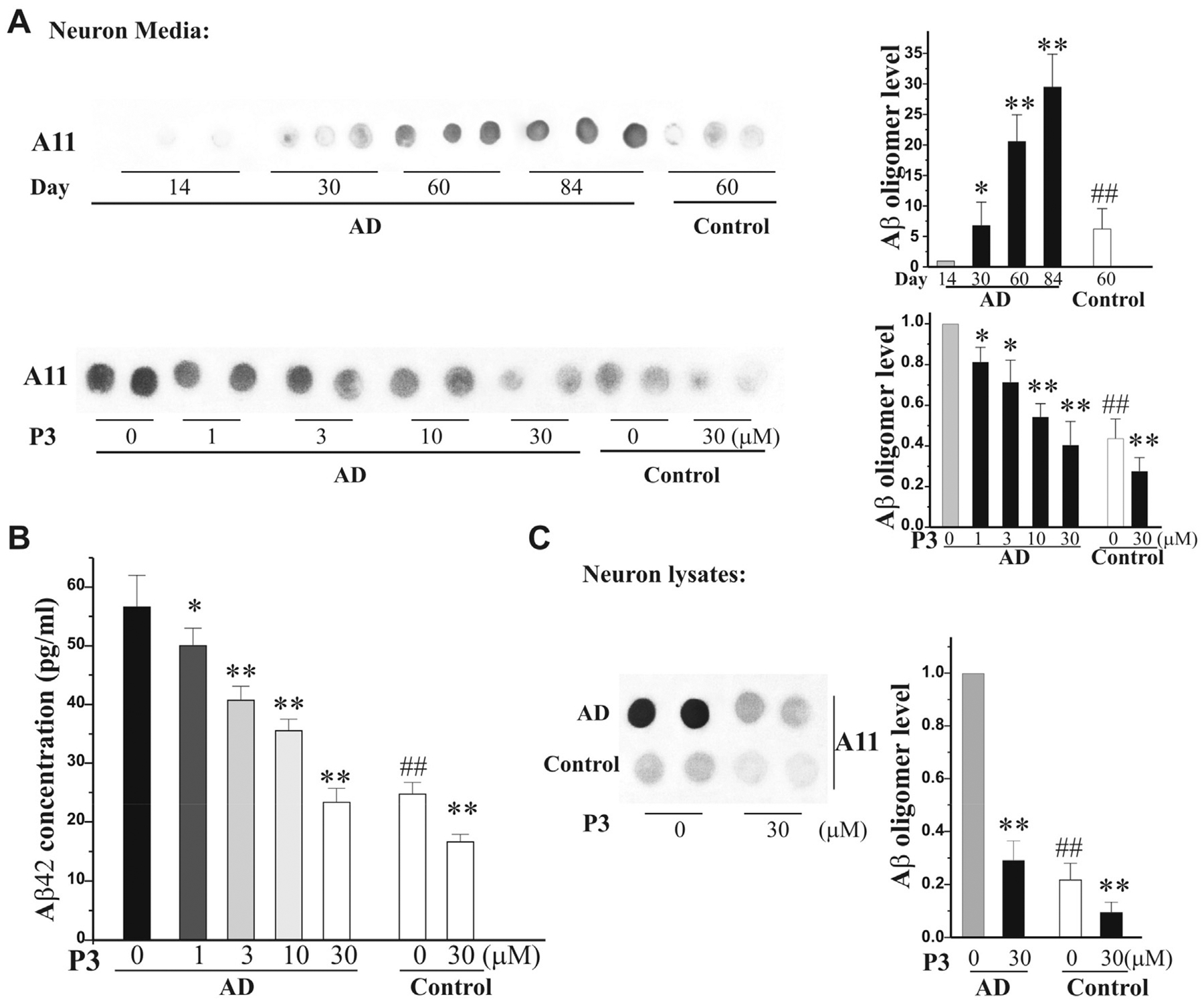

3.3. Novel peptide P3 reduces Aβ oligomers in iPSC neurons derived from AD patients

The lack of experimental access to live human brain cells has long hindered our ability to study complex neurodegenerative disorders. The breakthrough in the study of human diseases over the last decade has emerged from the development of technology to reprogram somatic cells into pluripotent cells, named induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), providing a renewable source of previously inaccessible human cell types. iPSC technology offers an unprecedented more opportunity to recapitulate the development of human diseases [17]. Significant progress has been made in developing methodologies for the targeted differentiation of human iPSCs (hiPSCs) from AD into several cell types in the nervous system, including cortical neurons and astrocytes. Studies show that neurons derived from patient-specific iPSCs recapitulate specific disease phenotypes, respond to drug treatments, and are valuable in mechanistic studies of complex human diseases at the cellular level [17]. We have successively established iPSC technology and induced the differentiation of hiPSCs from AD patient fibroblasts into cortical neurons. Compared with the corresponding controls, the conditioned media were collected from the hiPSC neurons from AD for the Aβ oligomer dot blot assay. The results show a time-dependent increase of Aβ oligomers from 14 to 84 at days in vitro (DIV). At 60 DIV, the neurons were treated with P3 at 1, 3, 10, and 30 μM for 24 h. The cell media and lysates were collected for the Aβ oligomer dot blot assay, and the media were collected for Aβ42 ELISA assays. We found that P3 reduced Aβ oligomers (Fig. 3A) and Aβ42 (Fig. 3B) in the media in a concentration-dependent manner in iPSC cortical neurons and Aβ oligomers in the cell lysates in the presence of 30 μM P3 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Peptide P3 reduces Aβ oligomers in hiPSC neurons.

A. P3 reduces Aβ oligomers in the media of AD iPSC neurons: Aβ oligomers increase in the media of AD iPSC neurons following culture at day 14–84. At day 60, the AD iPSC neurons were treated with P3 (1–30 μM) and the control iPSC neurons were treated with P3 (30 μM). The conditioned media (10 μl = 2 μl × 5 per dot) were collected for dot blot assay with A11 antibody. Left panels showed the quantification of Aβ oligomers relative to indicated groups (n = 3 of three independent experiments). B. The media were collected for the Aβ42 ELISA assay. C. The neuron lysates (6 mg per dot) were collected at the above same condition in the presence of P3 at 30 μM for dot blot assay. Left panel showed the quantification of Aβ oligomers relative to indicated groups (n = 3 of three independent experiments). All data in A to C were expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs its corresponding control (without P3); ##P < 0.01 vs the AD iPSC neuron group.

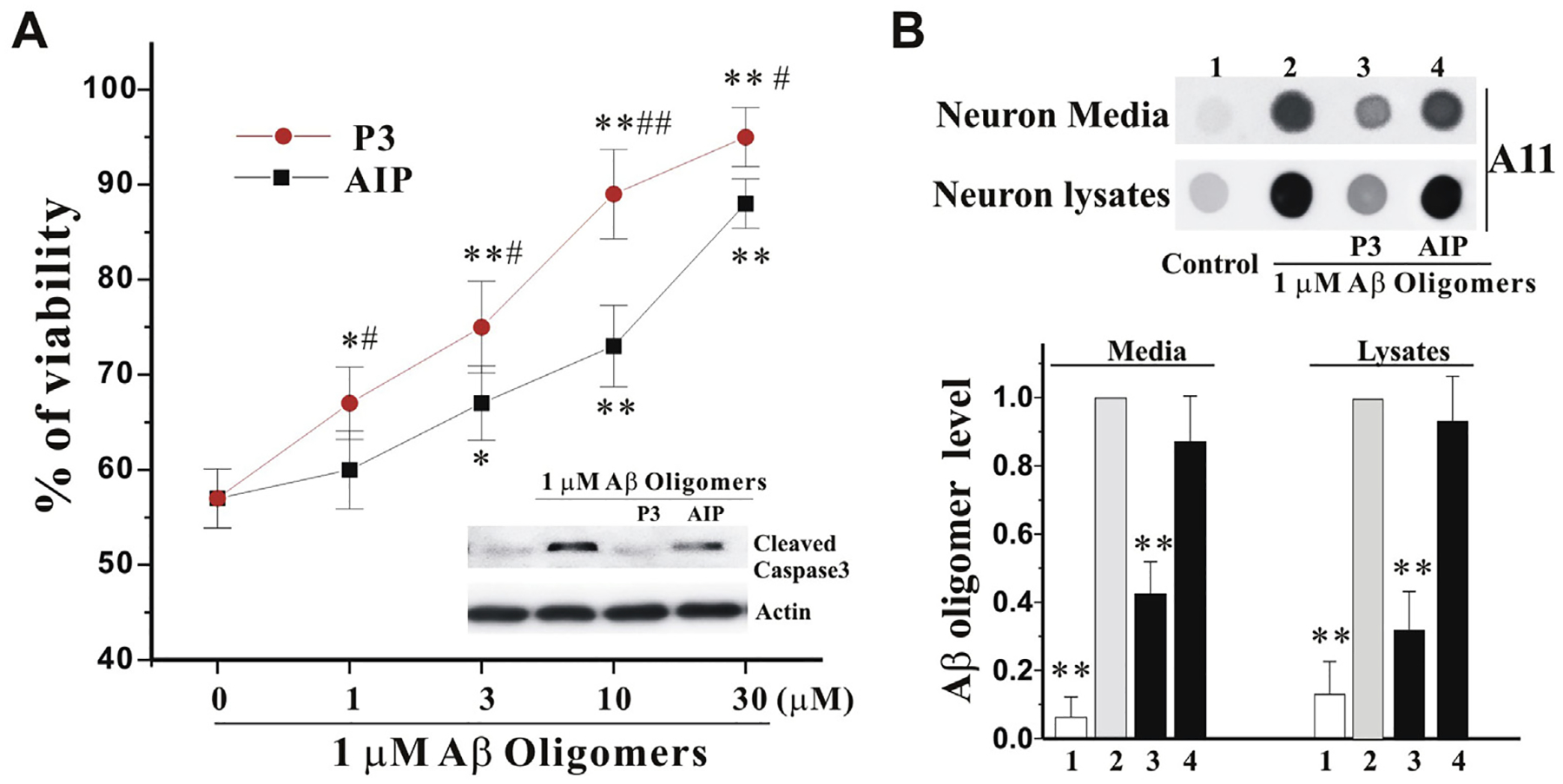

3.4. Novel peptide P3 protects cortical neurons from Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity

The previous study has shown that the AIP (RGTFEGKF) has neuroprotective activity against Aβ42 peptides in both SH-SY5Y and primary hippocampal neurons [20]. To determine whether our novel peptide P3 has neuroprotective activity, we employed our well-established Aβ oligomer model in primary cultured cortical neurons. At 12 DIV, the neurons were exposed to 1 μM Aβ oligomers for 4 h and then treated with P3 and AIP at indicated concentrations for 44 h more. The WST1 assay showed that both P3 and AIP rescued the neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers in a concentration-dependent manner and reduced the level of cleaved caspase 3 in presence of P3 and AIP at 30 μM, and P3 is more effective than AIP (Fig. 4A). More interestingly, P3, but AIP, dramatically reduced Aβ oligomers in both conditioned media and cell lysates (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Peptide P3 protects neurons from neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers.

A. Primary cultured cortical neurons were treated with 6-h pre-incubated Aβ oligomers (1 μM), in the presence of indicated increase concentrations of P3 and AIP for 42 h. The viability (%) was measured by WST1 and expressed as mean ± SEM, normalized to vehicle-treated neurons. N = 6, *p < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs AIP at the same concentration. The neuron lysates were collected from the above samples in the presence of both P3 and AIP at 30 mM for Western blot with cleaved caspase 3 antibody (Inset). B. The neurons were treated as the above in the presence of both P3 and AIP at 30 μM for 42 h. The neuron media (6 μl = 2 μl × 3 per dot) and lysates (4 μg per dot) were collected for dot blot assay with anti-A11 antibody (Top panel). Bottom panel showed the quantification of Aβ oligomers relative to Aβ oligomers alone group (n = 3 of independent experiments). All values are means ± SEM (**P < 0.01 vs the Aβ oligomers alone group).

4. Discussion

A successful development of highly effective approaches to halt the progression of AD relies on our understanding of the fundamental pathogenic mechanisms that trigger the relentless neuronal deterioration in the disease [2]. Although the exact mechanisms of AD are still unclear, accumulating evidence shows that Aβ oligomers play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of AD, and may be the principal causative factors of AD [2]. Numerous clinical trials based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis have been launched and failed one after another, but Biogen is pursuing a regulatory approval for aducanumab because this antibody targeting amyloid in the Phase III EMERGE trial has met its primary endpoint, showing a significant decrease in clinical decline [6]. Despite this promising, the antibody-based therapy needs to be modified because a) accumulated proteins cause AD while antibodies may further increase the burden of protein degradation systems which may have been damaged in AD [24], b) antibodies are too large to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and cellular membranes, while antibody depletion of targeted proteins may only shift the equilibrium between the intracellular and extracellular pools [25]; and c) antibodies only neutralize the proteins, but cannot effectively enhance the degradation of these proteins, which may cause secondary impairments [26].

In this study, we have demonstrated that our small peptide can reduce Aβ oligomers possibly via Hsc70-based autophagy. First, we apply several interacting ideas to design and modify the peptide: 1) selecting and identifying one specific Aβ oligomer-binding sequence [20], 2) linking it with TAT and the three CTMs [14], 3) adding three readily-oxidized amino acids into the sequence [11,21], and 4) incubating it with BHO to mildly oxidize the peptide [23]. The peptide with such profiles may efficiently bring Aβ oligomers into the lumen of endosomes and lysosomes. One challenge is whether oligomers with the peptide can pass through endosomes and lysosomes because the previous study showed that only unfolded proteins can pass through the lysosomal membrane [27]. We addressed this issue from the two ways: 1) based on the CMA process, two groups have established a peptide targeting a specific protein by interaction for degradation through CMA, indicating that CMA can accept the dimers of protein monomers and their interacting peptides (proteins) and unfolded proteins may be not necessary for CMA-based degradation [14,15]; and 2) eMI can use folded proteins, protein oligomers, and even protein fibers as its substrates for degradation [12]. We predicted that Aβ oligomers can be brought into late endosomes even though they are not recruited into lysosomes through CMA. Interestingly, our findings have demonstrated that our novel peptide can bring the oligomers into the mixture of endosomes and lysosomes or even highly purified lysosomes. This will expand the mechanistic knowledge of CMA. Indeed, Cuervo’s group also updated several points in CMA. Previous studies emphasized the role of CMA in protein quality control and only considered abnormal or damaged proteins with the CMA motif as the main CMA substrates. Increasing evidence shows that protein damage is not a requirement for CMA targeting. In other words, properly folded and fully functional proteins can become CMA substrates under specific conditions [28]. These remind us to constantly question old dogma for autophagy.

More importantly, we have found that our novel peptide can dramatically reduce Aβ oligomers in both media and cell lysates of iPSC neurons derived from AD patients and protect primary cultured cortical neurons from Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity possibly by directly neutralizing Aβ oligomers and promoting degradation of Aβ oligomers because our peptide P3 has a higher effects than its original peptide AIP [20]. Although underlying mechanisms are under investigation and the novel peptide effects urgently need to be confirmed in AD animal models, we have provided an alternative way to regulate Hsc70-based autophagy by directly manipulating potential substrates (Aβ oligomers) but not Hsc70 and LAMP2A. This is, for the first-time, proof-of-concept evidence that Hsc70-based autophagy can be used to degrade oligomers of proteins; therefore, the study may generate not only a new powerful tool for basic research, but also a mean of facilitating the development of effective therapeutics. By targeting Hsc70-based autophagy, we expect that the novel agent will represent highly promising drug candidate that marks significant progress in the fight against AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [AG058866 (WL), NS095269 (ZM) and NS107505 (ZM and ZW)] and the Department of Defense [W81XWH1910353 (ZW)].

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Zendehbad AS, Noroozian M, Shakiba A, Kargar A, Davoudkhani M, Validation of Iranian Smell Identification Test for screening of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult (2020) 1–6, 10.1080/23279095.2019.1710508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Selkoe DJ, Hardy J, The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years, EMBO Mol. Med 8 (2016) 595–608, 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Luo J, Warmlander SK, Graslund A, Abrahams JP, Cross-interactions between the alzheimer disease amyloid-beta peptide and other amyloid proteins: a further aspect of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, J. Biol. Chem 291 (2016) 16485–16493, 10.1074/jbc.R116.714576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Sarmiento J, Troncoso J, Jackson GR, Kayed R, Identification of oligomers at early stages of tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease, FASEB J 26 (2012) 1946–1959, 10.1096/fj.11-199851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT, The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer’s disease, Neuron 82 (2014) 756–771, 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Selkoe DJ, Alzheimer disease and aducanumab: adjusting our approach, Nat. Rev. Neurol (2019), 10.1038/s41582-019-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hashimoto T, Serrano-Pozo A, Hori Y, Adams KW, Takeda S, Banerji AO, Mitani A, Joyner D, Thyssen DH, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Spires-Jones TL, Finn MB, Holtzman DM, Hyman BT, Apolipoprotein E, especially apolipoprotein E4, increases the oligomerization of amyloid beta peptide, J. Neurosci 32 (2012) 15181–15192, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1542-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shankar GM, Walsh DM, Alzheimer’s disease: synaptic dysfunction and Abeta, Mol. Neurodegener 4 (2009) 48, 10.1186/1750-1326-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tai HC, Serrano-Pozo A, Hashimoto T, Frosch MP, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT, The synaptic accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau oligomers in Alzheimer disease is associated with dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, Am. J. Pathol 181 (2012) 1426–1435, 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li W, Yang Q, Mao Z, Chaperone-mediated autophagy: machinery, regulation and biological consequences, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 68 (2011) 749–763, 10.1007/s00018-010-0565-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li W, Nie T, Xu H, Yang J, Yang Q, Mao Z, Chaperone-mediated autophagy: advances from bench to bedside, Neurobiol. Dis (2018), 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tekirdag KA, Cuervo AM, Chaperone-mediated autophagy and endosomal microautophagy: joint by a chaperone, J. Biol. Chem (2017), 10.1074/jbc.R117.818237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Park JS, Kim DH, Yoon SY, Regulation of amyloid precursor protein processing by its KFERQ motif, BMB Rep. 49 (2016) 337–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fan X, Jin WY, Lu J, Wang J, Wang YT, Rapid and reversible knockdown of endogenous proteins by peptide-directed lysosomal degradation, Nat. Neurosci 17 (2014) 471–480, 10.1038/nn.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bauer PO, Goswami A, Wong HK, Okuno M, Kurosawa M, Yamada M, Miyazaki H, Matsumoto G, Kino Y, Nagai Y, Nukina N, Harnessing chaperone-mediated autophagy for the selective degradation of mutant huntingtin protein, Nat. Biotechnol 28 (2010) 256–263, 10.1038/nbt.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fu H, Li W, Lao Y, Luo J, Lee NT, Kan KK, Tsang HW, Tsim KW, Pang Y, Li Z, Chang DC, Li M, Han Y, Bis(7)-tacrine attenuates beta amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis by regulating L-type calcium channels, J. Neurochem 98 (2006) 1400–1410, 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wen Z, Nguyen HN, Guo Z, Lalli MA, Wang X, Su Y, Kim NS, Yoon KJ, Shin J, Zhang C, Makri G, Nauen D, Yu H, Guzman E, Chiang CH, Yoritomo N, Kaibuchi K, Zou J, Christian KM, Cheng L, Ross CA, Margolis RL, Chen G, Kosik KS, Song H, Ming GL, Synaptic dysregulation in a human iPS cell model of mental disorders, Nature 515 (2014) 414–418, 10.1038/nature13716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yang Q, Li W, She H, Dou J, Duong DM, Du Y, Yang SH, Seyfried NT, Fu H, Gao G, Mao Z, Stress induces p38 MAPK-mediated phosphorylation and inhibition of Drosha-dependent cell survival, Mol. Cell 57 (2015) 721–734, 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li W, Zhu J, Dou J, She H, Tao K, Xu H, Yang Q, Mao Z, Phosphorylation of LAMP2A by p38 MAPK couples ER stress to chaperone-mediated autophagy, Nat. Commun 8 (2017) 1763, 10.1038/s41467-017-01609-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barucker C, Bittner HJ, Chang PK, Cameron S, Hancock MA, Liebsch F, Hossain S, Harmeier A, Shaw H, Charron FM, Gensler M, Dembny P, Zhuang W, Schmitz D, Rabe JP, Rao Y, Lurz R, Hildebrand PW, McKinney RA, Multhaup G, Abeta42-oligomer Interacting Peptide (AIP) neutralizes toxic amyloid-beta42 species and protects synaptic structure and function, Sci. Rep 5 (2015) 15410, 10.1038/srep15410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Berlett BS, Stadtman ER, Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress, J. Biol. Chem 272 (1997) 20313–20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tjelle TE, Brech A, Juvet LK, Griffiths G, Berg T, Isolation and characterization of early endosomes, late endosomes and terminal lysosomes: their role in protein degradation, J. Cell Sci 109 (Pt 12) (1996) 2905–2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Finn PF, Dice JF, Ketone bodies stimulate chaperone-mediated autophagy, J. Biol. Chem 280 (2005) 25864–25870, 10.1074/jbc.M502456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Steele JW, Fan E, Kelahmetoglu Y, Tian Y, Bustos V, Modulation of autophagy as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease, Postdoc J 1 (2013) 21–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].van Dyck CH, Anti-Amyloid-beta monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease: pitfalls and promise, Biol. Psychiatr 83 (2018) 311–319, 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Panza F, Lozupone M, Dibello V, Greco A, Daniele A, Seripa D, Logroscino G, Imbimbo BP, Are antibodies directed against amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomers the last call for the Abeta hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease? Immunotherapy 11 (2019) 3–6, 10.2217/imt-2018-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tekirdag K, Cuervo AM, Chaperone-mediated autophagy and endosomal microautophagy: joint by a chaperone, J. Biol. Chem 293 (2018) 5414–5424, 10.1074/jbc.R117.818237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kaushik S, Cuervo AM, The coming of age of chaperone-mediated autophagy, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 19 (2018) 365–381, 10.1038/s41580-018-0001-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]