Abstract

Exposure to fluoride (F) or arsenite (As) through contaminated drinking water has been associated with chronic nephrotoxicity in humans. Autophagy is a regulated mechanism ubiquitous for the body in a toxic environment with F and As, but the underlying mechanisms of autophagy in the single or combined nephrotoxicity of F and As is unclear. In the present study, we established a rat model of prenatal and postnatal exposure to F and As with the aim of investigating the mechanism underlying nephrotoxicity of these pollutants in offspring. Rats were randomly divided into four groups that received NaF (100 mg/L), NaAsO2 (50 mg/L), or NaF (100 mg/L) with NaAsO2 (50 mg/L) in drinking water or clean water during pregnancy and lactation; after weaning, pups were exposed to the same treatment as their mothers until puberty. The results revealed that F and As exposure (alone or combined) led to significant increases of arsenic and fluoride levels in blood and bone, respectively. In this context, F and/or As disrupted histopathology and ultrastructure in the kidney, and also altered creatinine (CRE), urea nitrogen (BUN) and Uric acid (UA) levels. Intriguingly, F and/or As uptake induced the formation of autophagosomes in kidney tissue and resulted in the upregulation of genes encoding autophagy-related proteins. Collectively, these results suggest that nephrotoxicity of F and As for offspring exposed to the pollutants from in utero to puberty is associated with deregulation of autophagy and there is an antagonism between F and As in the toxicity autophagy process.

Keywords: fluoride, arsenite, autophagy, nephrotoxicity

Introduction

Inorganic arsenic (As3+, hereafter As) and fluoride (F− hereafter F) are recognized as the most dangerous inorganic contaminants of drinking water, which have become a serious public health concern because of their toxicity to humans and animals(Brahman et al. 2014; Chakraborti et al. 2016). F and As pollution has been detected in groundwater in many parts of China, especially in semi-arid areas of northern China, including Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Ningxia (Wen et al. 2013).

Evidence has revealed that F-polluted drinking water causes negative effects on teeth and bones but can also damage soft tissues, including nephrotoxicity, vascular toxicity, immune responses, even chronic kidney damage(Chattopadhyay et al. 2011; Dharmaratne 2019; Dong et al. 2015; Jimenez-Cordova et al. 2018; Ma et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2018b). The kidneys are the major organs most susceptible to As and other metallic elements exposure, which is associated with renal dysfunction and structural damage, ultimately causing chronic nephrotoxicity and even cancer(Cheng et al. 2017a; Chu et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2016; Saint-Jacques et al. 2018). However, although the nephrotoxicity of F or As has been confirmed, the underlying combined toxicity still needs to be clarified.

A survey conducted in India indicated that 6 million children suffered from fluorosis and arseniasis (Chakraborti et al. 2016). Therefore, F and As exposure from early in life (in utero and childhood), as specific life stages, may be more sensitive to F and As in the environment than ordinary adults(Das et al. 2018). It has been suggested that in prenatal and early life periods, humans are more susceptible to toxic effects of As and prenatal arsenic exposure can affect the growth and morbidity of infant and child(Bolt and Hengstler 2018; Ettinger et al. 2017; Gliga et al. 2018; Nelson-Mora et al. 2018). Epidemiological surveys in Mexico revealed that exposure to As in early life resulted in As accumulation in the body, as evidenced by high As levels in children’s urine (above 50 μg/L)(Mendez-Gomez et al. 2008), and the other investigations speculate that early exposure to As may result in genotoxicity, lung dysfunction, and kidney injury (Cardenas-Gonzalez et al. 2016; Ettinger et al. 2017; Recio-Vega et al. 2015). In addition, F posed a significant risk of dental fluorosis in infants and children(Samal et al. 2015)and was closely associated with kidney damage in childhood(Khandare et al. 2017; Xiong et al. 2007). However, although some studies investigated toxic effects of F and As exposure from the early life (in utero and childhood), the effects of combined F and As exposure and its underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be clarified.

Autophagy, as a regulated mechanism ubiquitous in eukaryotic cells, can destroy damaged or excessive proteins, thus supporting cellular homeostasis and regulating cell responses to environmental stresses and adverse conditions, including exposure to pollutants(Chen et al. 2011; Chiarelli and Roccheri 2012; Rocha et al. 2011). Previous studies indicate that autophagy is involved in the damage of the rat reproductive system due to F exposure from the early life to young adulthood(Zhang et al. 2016) and that it is induced by As, which stimulates autophagy-related signaling pathways in the developing mouse brain(Chiarelli and Roccheri 2012; Manthari et al. 2018). A previous study revealed that aberrant regulation of autophagy was linked to cell death in the kidney and was involved in acute kidney injury, development of polycystic kidney syndrome, and chronic renal disease(Chu et al. 2018; Havasi and Dong 2016). Intriguingly, autophagy is a well-studied mechanism, can be regulated through the mitochondrial oxidative stress and its downstream pathway(Cai et al. 2018; Gong et al. 2019; Song et al. 2017; Yamashita and Kanki 2017). Meanwhile, our previous study has also been revealed that exposure to high-dose As and/or F inhibited the activity of antioxidant enzymes and increased the generation of malondialdehyde, moreover, As and/or F exposure caused extensive swelling of mitochondria on kidney ultrastructure (Tian et al. 2019). Therefore, combined the literatures with our available results, we speculated and hypothesized that the autophagy may play a role in the nephrotoxicity of F and As.

Increasing investigations have shown that co-exposure of F and As has become a common global health problem. An investigation conducted in Mexico that revealed a possible interaction between F and As and its related health risks deserves immediate attention(Gonzalez-Horta et al. 2015). In a toxicity study of bone, it was found that there is an interaction between F and As(Zeng et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2014). Some studies in animal and cell models showed that the antagonism between F and As weakens toxic effects of each substance(Flora et al. 2011; Ma et al. 2017), whereas others found that F and As co-exposure potentiated developmental toxicity compared to F and As alone(Jiang et al. 2014; Rocha et al. 2011). Still others found no interaction between F and As(Mittal et al. 2018; Sarkozi et al. 2015). Interestingly, our previous studies were the first to confirm the interaction between F and As about the changes of oxidative stress in nephrotoxicity by variance analysis(Tian et al. 2019). However, the underlying interaction of nephrotoxicity mechanisms between F and As remain to be clarified.

In the present study, we tested this hypothesis by establishing a rat model in which offspring were subjected to sub-chronic treatment with high-dose F, As, or their combination, from early life (in utero and childhood) to puberty, and investigated the status of kidney tissue, distribution of autophagosomes, and changes in the expression of autophagy-related genes. In this context, we then analyzed and answered the question of whether there is an antagonism between F and As.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Sodium fluoride (NaF) and sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animals and treatment

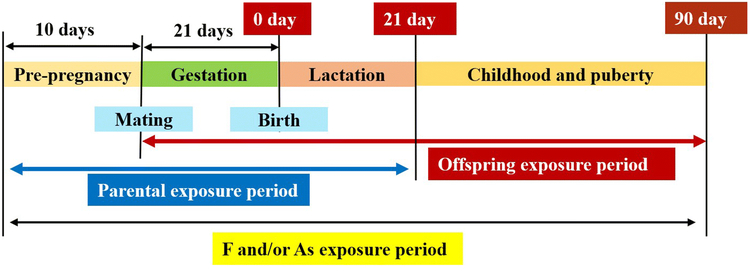

Healthy adult Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g) were provided and kept in a suitable environment in the Laboratory Animal Center of Shanxi Medical University (Taiyuan, China). Eight female rats and four male rats kept separately were randomly divided into four groups: control receiving sterile water, and exposure groups receiving 100 mgL NaF (F group), 50 mg/L NaAsO2 (As group), or 100 mg/L NaF and 50 mg/L NaAsO2 (F+As group) in drinking water. The dosages were chosen based on a previous study of combined toxicity of F and As in rat offspring(Tian et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2017). After 10 days of exposure, female and male rats from respective groups were put together for mating at the 2:1 male to female ratio. Once the establishment of a vaginal plug indicating successful mating and day 0 of pregnancy was confirmed, females were separated from males. Pregnant rats were provided free access to drinking water from the first day of pregnancy to the 21st day after giving birth. Rat pups were exposed to As/F through parental lactation during the 21-day period; then, six normal male offspring were randomly selected from each group and subjected to the same As/F treatment as their mothers until postnatal day 90 (Fig. 1). The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanxi Medical University.

Fig. 1.

Schedule of rat offspring exposure to F, As, or their combination

Detection of As accumulation in blood

50 μL of the blood sample were aspirated into an Erlenmeyer flask, then 5 mL of mixed acid and heat were added on a hot plate, until digestion to obtain colorless crystals. After digestion, 1 mL of the mixture solution of sulfocarbamide and ascorbic acid was added the digested sample, then dissolved in deionized water and made up to reach a total volume of 10 mL. Finally, the concentration in diluted samples were determined by an atomic fluorescence spectrometer (AFS-9700, Beijing Haiguang, China). Detection of As accumulation in rat blood through this method has been reported previously(Jing et al. 2012).

Detection of F accumulation in bone

The configuration of the fluorine standard solution is: 1×10−1 mol/L, 1×10−2 mol/L, 1×10−3 mol/L, 1×10−4 mol/L, 1×10−5 mol/L. The fluoride standard solutions were mixed with total ion strength adjustment buffer (TIS AB II) in a 1:1 ratio (v/v) for quantification. The potential value was measured by a fluoride ion selective electrode method, and a fluoride standard curve was drawn.

An appropriate amount (25 mg) of the femur was placed in a mortar and dried at 105°C for 4 hours, and the dry bone was weighed. The dry bone was placed in a muffle furnace for 5 hours, the ashes were collected and weighed, and the weight ratio coefficient “a” of the ashes/dry bone was calculated. Weigh the right amount of ashes and mark them as "w". In order to stabilize the samples for fluoride assessment, 5 mL of HCl 0.25M was added to the femoral ashes (w) of the samples. Then, the bone samples were mixed with 12.5 mL total ion strength adjustment buffer (TISAB II) and made up to 25 mL with ultrapure water. Finally, the potential value was determined by fluoride ion selective electrode method, and the concentration (A) of fluoride ion was calculated by the standard curve(Linhares et al. 2018). The fluoride content of the bone was assessed as follows:

Histopathological examination

Histopathological analysis was done to assess the extent of kidney damage(Yan et al. 2019). The fresh kidneys were cut, washed, and quickly fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then embedded in paraffin. They were then sliced, spread, dried, dewaxed, stained, placed in a neutral resin, and allowed to dry naturally. Finally, the rat kidney tissue stained slides were observed using the Olympus BX53 optical microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Ultrastructure of the kidney

Kidneys were extracted, washed with physiological saline, cut into 1-mm3 pieces, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 hours at 4°C, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol embedded in epoxy resin, trimmed, sectioned, and stained as described previously(Yan et al. 2015). Sections were observed and photographed under a JEM-1011 transmission electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Biochemical analysis

Whole blood was collected and allowed to stand for 2 hours before centrifugation at 5000 RPM for 10 minutes to separate serum, which was then used to measure creatinine (CRE) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) with test kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). The results were expressed as μmol/L CER and μmol/L BUN.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from kidney tissue using the RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Dalian, China) and assessed for concentration and purity by absorbance at 260 nm/280 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara). Each qPCR was performed in a volume of 20 μL including 10 μL of SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Takara), 0.8 μL of each primer (10 μM), 6.4 μL of double-distilled water, and 2 μL of cDNA in a real-time PCR detection system (Line Gene 9660; Bori, Hangzhou, China) at the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. Primers were designed according to mRNA sequences retrieved from PubMed and synthesized by Takara (Table 1). Relative mRNA expression of each gene was determined by the 2−ΔΔCt method as described previously(Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for quantitative real-time PCR

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Accession no. | Primer length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beclin1-F | GAAACTGGACACGAGCTTCAAGA | NM_001034117.1 | 23 |

| Beclin1-R | ACCATCCTGGCGAGTTTCAATA | 22 | |

| Lc3-F | AGCTCTGAAGGCAACAGCAACA | NM_022867.2 | 22 |

| Lc3-R | GCTCCATGCAGGTAGCAGGAA | 21 | |

| p62-F | AAGCTGCCCTGTACCCACATC | NM_175843.4 | 21 |

| p62-R | ACCCATGGACAGCATCTGAGAG | 22 | |

| Actb-F | GGAGATT ACT GCCCT GGCTCCTA | NM_031144.2 | 23 |

| Actb-R | GACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTGCTG | 24 |

Western blotting analysis

Kidneys were extracted from three rats in each treatment group, and 30 mg of kidney tissue was treated with RIPA lysis buffer containing proteinase inhibitors. The homogenization was carried out with ultrasonic crusher (CCT-3300, Chengdu, China) and centrifuged. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA assay, and 50 μg of total protein was separated by SDS-PAGE in 10% gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST), and then incubated with primary antibodies against β-actin Lc3, Beclin1 and p62 (diluted 1:1,000; CST, USA) overnight at 4°C. After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:4,000) for 1 hour at room temperature, the membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline/0.1% Tween-20 and signals were detected using an ECL luminescence reagent and observed using an electrophoresis gel imaging and analysis system (G:Box Chemi XX9; Syngene, London, UK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). All data were expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed for differences between groups by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); P < 0.05 was considered significant. Variance analysis was used to detect the interaction between two factors; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

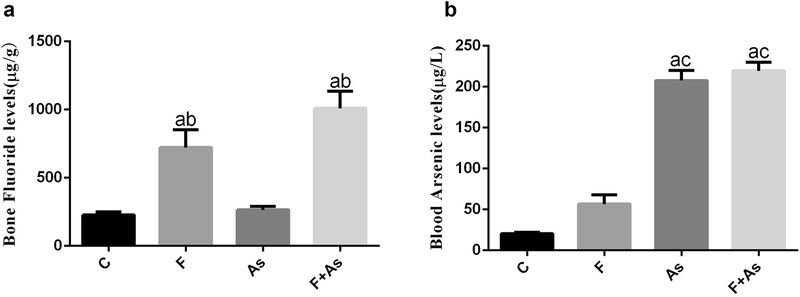

The bone fluoride levels and blood arsenic levels in rat offspring.

As- and F-exposure, alone or combined, led to significant increase of arsenic and fluoride levels in blood and bone, respectively. The levels of fluoride in the F group and the combined group was significantly higher than that in the control group and the As group (Fig 2a). The levels of arsenic in the As group and the combined group was significantly higher than that in the control group and the F group (Fig 2b).

Fig. 2.

F and As levels in blood or bone, respectively. The data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 6); a, P < 0.01 vs control; b, P < 0.01 vs As; c, P < 0.01 vs F.

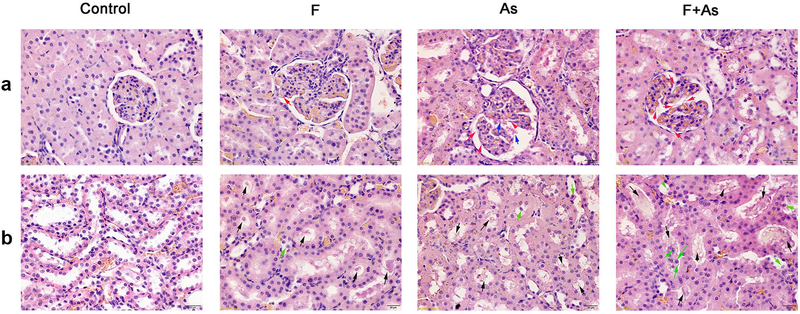

The histopathology in the kidney of rat offspring

As shown in Fig. 3a, in the control group, the glomerular was regular and clear, and the basement membrane was evenly distributed and had normal thickness. However, in the treatment groups, the glomerular basement membrane was irregular thickened. In addition, broken red blood cells were found in the vascular lumen in the arsenic group. As shown in Fig. 3b, compared with the control group, kidney tubular epithelial cells were swollen, granular and vacuolar. In addition, the epithelial cells of the renal tubules shed into the lumen, and there were cell fragments in the treatment groups.

Fig. 3.

Histopathological changes in the kidney caused by exposure to F, As, or their combination. Magnification, ×400; a Histopathological change of glomerular, red arrows indicated irregular thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, blue arrows indicated broken red blood cells in the vascular cavity; b Histopathological change of kidney tubule, black arrows indicated kidney tubular epithelial vacuolar degeneration and cell debris, green arrows indicated kidney tubular epithelial cells fall off into the lumen.

The ultrastructure in the kidney of rat offspring

In the control group, the glomerular basement membrane was evenly distributed and had normal thickness; the distribution of podocytes and foot processes was regular and clear. In rats treated with F alone, some foot processes were fused and swollen, and the basement membrane was thickened, whereas in those treated with As, thickening of the basement membrane was observed in a larger area, podocyte foot processes were swollen and their fusion extended. In the F and As group, the pore size of the endothelial fenestrae was increased, and extensive endothelial fenestrae are disrupted and scattered to the lumen (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Ultrastructural changes in the kidney caused by exposure to F, As, or their combination. a Glomerular ultrastructure. Magnification, ×6000; End, BM, P and FP indicate endothelium, basement membrane, podocytes and foot process fusion, respectively. b Ultrastructure of proximal tubular epithelial cells. Magnification, ×12000; M, PMP indicate mitochondria, plasma membrane pleats

Regular plasma membrane pleats and mitochondria were observed in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells of the control group. In all treatment groups, plasma membrane pleats of renal tubular epithelial cells were sparse and the mitochondria disordered. The most severe effects were revealed in the As group, where cavitations inside the mitochondria, partial rupture of the cristae, and even vacuoles were observed (Fig. 4b).

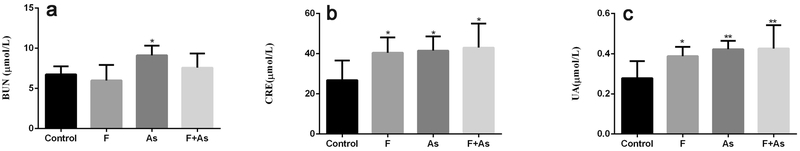

The serum CRE, BUN and UA levels in offspring

Renal function was evaluated by testing serum CRE, BUN and UA levels. BUN levels were markedly increased by As alone, whereas F alone and combination of F and As also tended to upregulate CRE, but the change was not statistically significant (Fig. 5a). The results indicated that CRE and UA levels were significantly higher in all toxin-exposed groups compared to those in the control group (Fig. 5b-c).

Fig. 5.

Effects of F, As, or their combination on serum BUN (a), CRE (b) and UA(c) in rat offspring. The data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 6); *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs control.

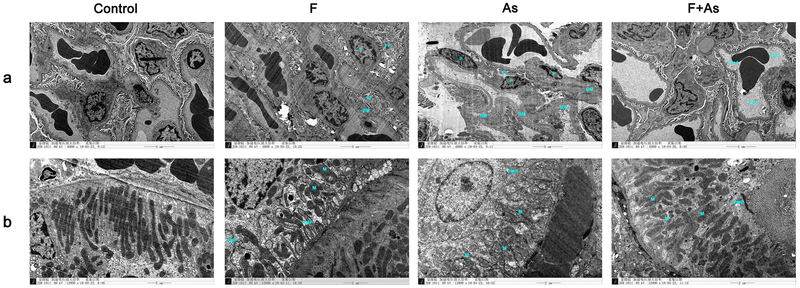

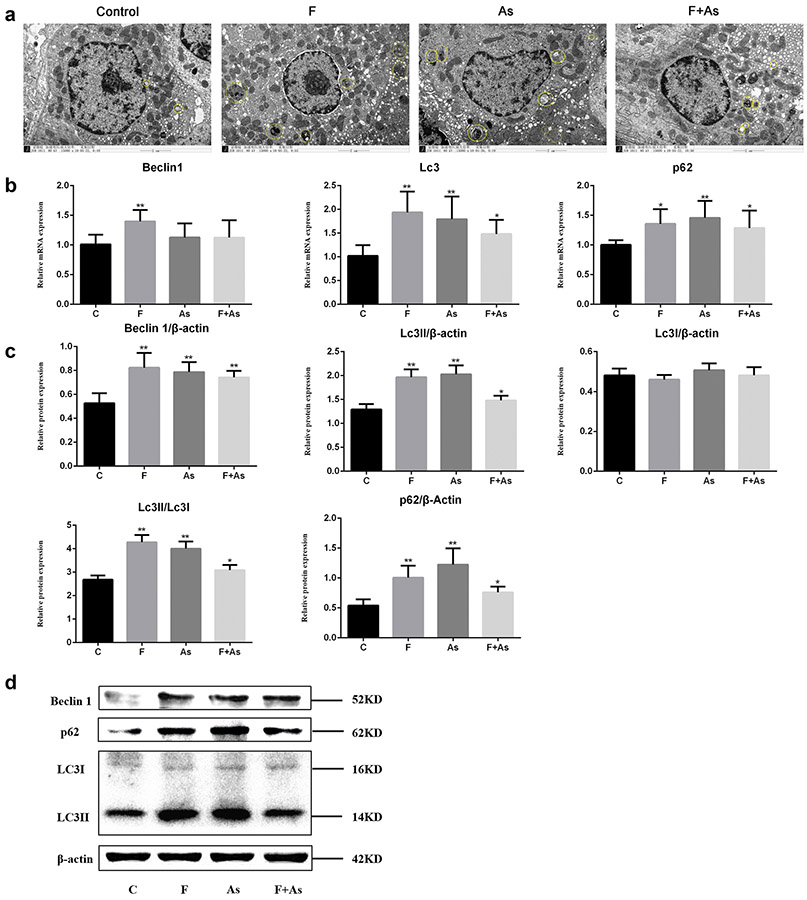

The distribution of autophagosomes and the expression of autophagy-related genes in the kidney of rat offspring

In each group, autophagosomes were concentrated around the nucleus of renal tubular epithelial cells. We observed vesicular structures surrounded by the bilayer membrane, which included proteins; visually discernible organelles were lysosomes and mitochondria. As shown in the micrographs, the highest number of autophagosomes were observed in the As or F group. The number of autophagosomes in each group within the field of view was: 2 in the control group, 6 in the F group, 8 in the As group, and 5 in the combined group (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

a Distribution of autophagosomes in kidney cells of rat offspring exposed to F, As, or their combination. Autophagosomes in the control group and groups treated with F, As, or F+As are circled. Magnification, ×15000; The yellow circles indicate autophagosomes. b The mRNA expression of genes coding for Lc3, Beclin 1, and p62 was analyzed by qPCR. c The protein expression of genes coding for Lc3, Beclin 1, and p62 was analyzed by Western blotting. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6); *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs control

To further investigate the role of autophagy in the toxicity of F and As for the kidney, we evaluated their effects on mRNA expression of the Beclin1, Lc3, and p62 genes encoding autophagy-related proteins Beclin1, Lc3, and p62, respectively. The results indicated that in all toxin-exposed groups, the expression of these genes was higher than in the control group. Thus, mRNA levels of all analyzed genes were significantly increased in F-treated rats, and those of Lc3 and p62 genes were significantly increased in As-treated rats compared to control rats. Interestingly, in the F+As group, only genes Lc3 and p62 were significantly upregulated (Fig. 6b).

In this context, we have evaluated the protein expression levels of Beclin1, Lc3II/ Lc3I, and p62 to determine the effect of F and As on kidney autophagy. As shown in Fig. 6c-d, compared with the control group, the Beclin1, Lc3II/ Lc3I, and p62 protein levels were significantly increased in all toxin-exposed groups.

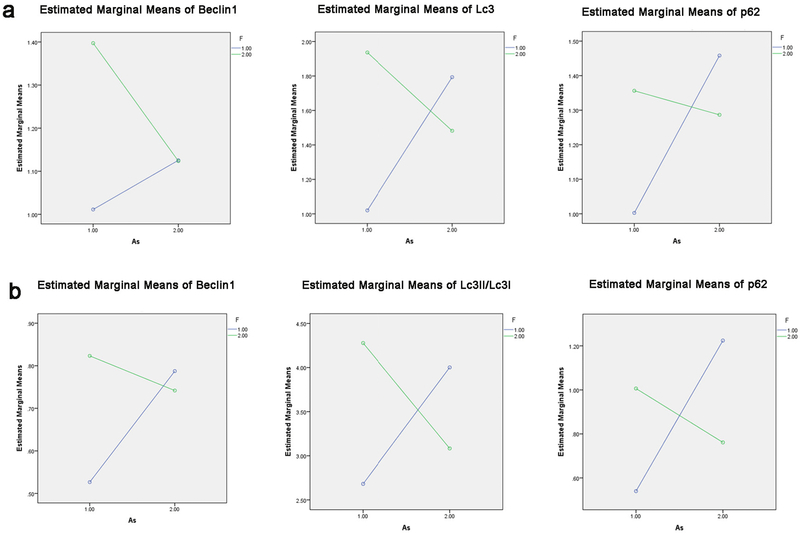

The joint action of F and As exposure on the toxicity of kidney autophagy-related genes.

Variance analysis results of the autophagy-related gene experiment showed an interaction between F and As. In Fig.7a, the mRNA results of Beclin1(F= 4.372; P=0.050), Lc3(F=16.168; P=0.001), and p62(F=7.062; P=0.015) genes showed that F and As exposure may produce a joint action on the toxicity of kidney autophagy-related genes. Consistent with mRNA expression, protein expression of Beclin1(F=21.828; P=0.000), Lc3II/Lc3I (F=142.078; P=0.000), and p62(F=38.501; P=0.000) also showed an interaction between F and As (Fig.7b). The mRNA and protein expressions of autophagy related genes (Beclin1, Lc3II/Lc3I, and p62) all showed interaction between F and As by variance analysis , and this further results showed that the sum of gene expressions in the single group was higher than that in the combined group, moreover, there are the antagonism between F and As.

Fig. 7.

a Interaction between F and As on the mRNA experiment of Lc3, Beclin 1, and p62. b Interaction between F and As on the protein experiment of Lc3, Beclin 1, and p62.

Discussion

Long-term exposure to excessive F or As concentrations through contaminated drinking groundwater is a threat to the physical development and health of young children(Smith et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2017). A survey conducted in Chile indicated that early-life (in utero and childhood) environmental exposure to As in drinking water increased the mortality rate in young adults(Smith et al. 2012). These findings indicate children (with early-life environmental exposure to F and As) may be more sensitive to F and As exposure in the environment than ordinary adults(Das et al. 2018). Therefore, to better mimic the hazards of early-life (in utero and childhood) environmental exposure to F and As, we have established an animal model that are exposed to these pollutants since gestation and through the neonatal period to puberty. Remarkably, our findings showed that F and As exposure alone or combined led to significant increase of arsenic and fluoride levels in blood an d bone, respectively, confirming the successful establishment of animal models.

The kidney is the main organ that excretes toxic substances of F and As, which can promote chronic nephrotoxicity by damaging renal tubules, decreasing glomerular filtration rate, and causing renal dysfunction(Cheng et al. 2017a; Khandare et al. 2017; Wen et al. 2013). In this context, we used our model of long-term sub-chronic F and As exposure from day 0 of gestation until day 90 post-delivery to clarify the pathogenic outcomes of F/As-contaminated water intake in the kidney. As expected, our results indicate that F and As exposure caused ultrastructural changes of glomeruli and renal proximal convoluted epithelial cells; the effect of As alone was the most severe. Consistent with these observations, F and As alone or in combination increased serum levels of CRE and UA, moreover, BUN was significantly increased in the As group. Thus, sub-chronic exposure to F and As starting from early embryogenesis to puberty can cause kidney damage in offspring.

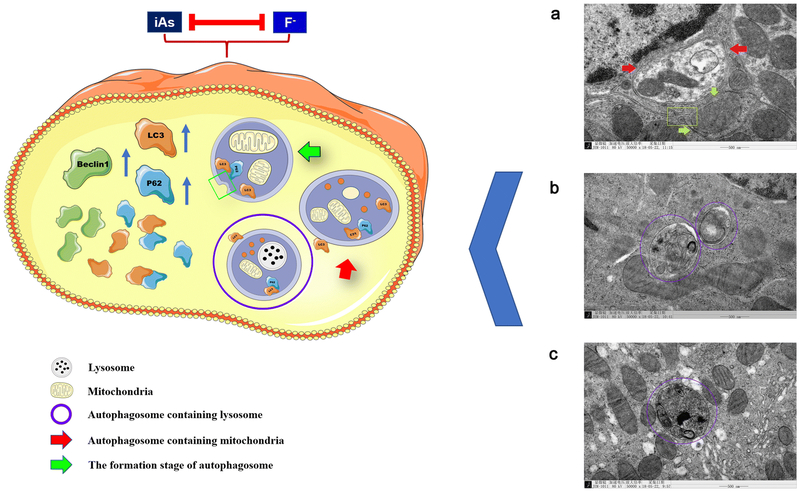

The main novel finding of the current study is the involvement of autophagy in the nephrotoxicity of F and As. Autophagy is a catabolic process providing delivery and degradation of cytoplasmic material (proteins, organelles and macromolecular complexes) in lysosomes, which is accompanied by the formation, maturation and fusion of autophagosomes(Liu et al. 2017). Interestingly, we clearly observed the started formation of autophagosome that the double-layered phagophore that try to wrap around the mitochondria are closing in Fig 8a. We also observed the maturation of autophagosome, such as the formation of autolysosome in Fig 8b-c. Remarkably, we observed that the numbers of autophagosomes in renal tubular epithelial cells were increased in all treated offspring compared to control, but were the highest in the F and As groups. Autophagy is also tightly regulated by various factors in throughout the autophagic flux, such as the genes of Beclin1, Lc3 and p62. (Yu et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018). Beclin1 is critical for the early stages of autophagy as it regulates other autophagy-related factors and activates downstream gene transcription(Cheng et al. 2017b). Microtubule-associated protein Lc3 is essential for the formation of autophagosomes, and its expression is an indicator of the autophagosome number in the cell(Park et al. 2016). Our results demonstrated that sustained sub-chronic treatment with F and/or As significantly upregulated expression of the Beclin1-encoding gene in offspring kidneys, suggesting that F and As affect the occurrence of early autophagy. In this context, we found a significant increase in Lc3 expression in response to F or As exposure, which was consistent with the distribution of autophagosomes in the micrographs. Therefore, we speculate that F and As affect autophagosome formation. Downstream of autophagosome formation, autophagy receptor p62 binds to Lc3 promoting autophagosome degradation, and p62 accumulation indicates the inhibition of autophagosome turnover(Park et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2018a). In this text, F and As alone and combination upregulated the expression of the p62-encoding gene, suggesting that these toxicants may block the downstream autophagic flow by inhibiting the degradation of autophagosomes.

Fig. 8.

Model of F and As induced kidney injury. Deregulation of autophagy is involved in kidney toxicity of fluoride and arsenic exposure during gestation to puberty in rat offspring.

To date, the literature has not strongly supported that the interaction between F and As and its related health risks requires immediate attention. Our previous results show the existence of an interaction relationship between As and F on oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation (Ma et al. 2017; Ma et al. 2012; Tian et al. 2019). In this context, the mRNA and qualitative and quantitative protein expression of autophagy-related genes showed an antagonism between F and As, interestingly, it is the first time to confirm the relationship between F and As on autophagy by variance analysis. Collectively, these data indicate an antagonism between F and As effects on autophagy of nephrotoxicity exposed to the F/As combination; however, interaction between F and As should be validated in further studies.

In summary, our study evaluated, for the first time, the role of autophagy in nephrotoxicity of sub-chronic exposure to high-dose F, As, or their combination from early life (in utero and childhood) to puberty. In addition, we made an innovative discovery that the toxicants induced autophagosome formation while inhibiting their degradation in kidney tissue. Our results indicate that F, and especially As alone, produced stronger effects on renal autophagy than their combination, suggesting a cross-talk between the respective molecular pathways (Fig. 8). Overall, our findings provide new insight into the role of autophagy in the nephrotoxicity of F and As in offspring, which should contribute to understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms for future prevention and treatment of endemic diseases caused by these pollutants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773405), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2016M600199), the Program for the Outstanding Innovative Teams of Higher Learning Institutions of Shanxi, the Outstanding Youth Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (201701D211008), the Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (2017-058), and the PhD Start-up Fund of Shanxi Medical University (BS03201647). X.R. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (ES022629).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Bolt HM, Hengstler JG (2018) Contemporary trends in toxicological research on arsenic. Archives of toxicology 92(11):3251–3253 doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2311-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahman KD, Kazi TG, Baig JA, Afridi HI, Khan A, Arain SS, Arain MB (2014) Fluoride and arsenic exposure through water and grain crops in Nagarparkar, Pakistan. Chemosphere 100:182–9 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, She M, Xu M, Chen H, Li J, Chen X, Zheng D, Liu J, Chen S, Zhu J, Xu X, Li R, Li J, Chen S, Yang X, Li H (2018) GLP-1 treatment protects endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced autophagy and endothelial dysfunction. International journal of biological sciences 14(12):1696–1708 doi: 10.7150/ijbs.27774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas-Gonzalez M, Osorio-Yanez C, Gaspar-Ramirez O, Pavkovic M, Ochoa-Martinez A, Lopez-Ventura D, Medeiros M, Barbier OC, Perez-Maldonado IN, Sabbisetti VS, Bonventre JV, Vaidya VS (2016) Environmental exposure to arsenic and chromium in children is associated with kidney injury molecule-1. Environmental research 150:653–662 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti D, Rahman MM, Chatterjee A, Das D, Das B, Nayak B, Pal A, Chowdhury UK, Ahmed S, Biswas BK, Sengupta MK, Lodh D, Samanta G, Chakraborty S, Roy MM, Dutta RN, Saha KC, Mukherjee SC, Pati S, Kar PB (2016) Fate of over 480 million inhabitants living in arsenic and fluoride endemic Indian districts: Magnitude, health, socio-economic effects and mitigation approaches. Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology : organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements (GMS) 38:33–45 doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay A, Podder S, Agarwal S, Bhattacharya S (2011) Fluoride-induced histopathology and synthesis of stress protein in liver and kidney of mice. Archives of toxicology 85(4):327–35 doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0588-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Graziano JH, Parvez F, Liu M, Slavkovich V, Kalra T, Argos M, Islam T, Ahmed A, Rakibuz-Zaman M, Hasan R, Sarwar G, Levy D, van Geen A, Ahsan H (2011) Arsenic exposure from drinking water and mortality from cardiovascular disease in Bangladesh: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 342:d2431 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YY, Huang NC, Chang YT, Sung JM, Shen KH, Tsai CC, Guo HR (2017a) Associations between arsenic in drinking water and the progression of chronic kidney disease: A nationwide study in Taiwan. Journal of hazardous materials 321:432–439 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Zhu Q, Dee R, Opheim Z, Mack CP, Cyr DM, Taylor JM (2017b) Focal Adhesion Kinase-mediated Phosphorylation of Beclin1 Protein Suppresses Cardiomyocyte Autophagy and Initiates Hypertrophic Growth. The Journal of biological chemistry 292(6):2065–2079 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.758268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarelli R, Roccheri MC (2012) Heavy metals and metalloids as autophagy inducing agents: focus on cadmium and arsenic. Cells 1(3):597–616 doi: 10.3390/cells1030597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BX, Fan RF, Lin SQ, Yang DB, Wang ZY, Wang L (2018) Interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in lead(II)-induced cytotoxicity of primary rat proximal tubular cells. Journal of inorganic biochemistry 182:184–193 doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das N, Das A, Sarma KP, Kumar M (2018) Provenance, prevalence and health perspective of co-occurrences of arsenic, fluoride and uranium in the aquifers of the Brahmaputra River floodplain. Chemosphere 194:755–772 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmaratne RW (2019) Exploring the role of excess fluoride in chronic kidney disease: A review. Human & experimental toxicology 38(3):269–279 doi: 10.1177/0960327118814161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YT, Wang Y, Wei N, Zhang QF, Guan ZZ (2015) Deficit in learning and memory of rats with chronic fluorosis correlates with the decreased expressions of M1 and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Archives of toxicology 89(11):1981–91 doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1408-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger AS, Arbuckle TE, Fisher M, Liang CL, Davis K, Cirtiu CM, Belanger P, LeBlanc A, Fraser WD (2017) Arsenic levels among pregnant women and newborns in Canada: Results from the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) cohort. Environmental research 153:8–16 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora SJ, Pachauri V, Mittal M, Kumar D (2011) Interactive effect of arsenic and fluoride on cardio-respiratory disorders in male rats: possible role of reactive oxygen species. Biometals : an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine 24(4):615–28 doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9412-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliga AR, Engstrom K, Kippler M, Skroder H, Ahmed S, Vahter M, Raqib R, Broberg K (2018) Prenatal arsenic exposure is associated with increased plasma IGFBP3 concentrations in 9-year-old children partly via changes in DNA methylation. Archives of toxicology 92(8):2487–2500 doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2239-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong ZG, Wang XY, Wang JH, Fan RF, Wang L (2019) Trehalose prevents cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity by blocking Nrf2 pathway, restoring autophagy and inhibiting apoptosis. Journal of inorganic biochemistry 192:62–71 doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Horta C, Ballinas-Casarrubias L, Sanchez-Ramirez B, Ishida MC, Barrera-Hernandez A, Gutierrez-Torres D, Zacarias OL, Saunders RJ, Drobna Z, Mendez MA, Garcia-Vargas G, Loomis D, Styblo M, Del Razo LM (2015) A concurrent exposure to arsenic and fluoride from drinking water in Chihuahua, Mexico. International journal of environmental research and public health 12(5):4587–601 doi: 10.3390/ijerph120504587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havasi A, Dong Z (2016) Autophagy and Tubular Cell Death in the Kidney. Seminars in nephrology 36(3):174–88 doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Su J, Yao S, Zhang Y, Cao F, Wang F, Wang H, Li J, Xi S (2014) Fluoride and arsenic exposure impairs learning and memory and decreases mGluR5 expression in the hippocampus and cortex in rats. PloS one 9(4):e96041 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Cordova MI, Cardenas-Gonzalez M, Aguilar-Madrid G, Sanchez-Pena LC, Barrera-Hernandez A, Dominguez-Guerrero IA, Gonzalez-Horta C, Barbier OC, Del Razo LM (2018) Evaluation of kidney injury biomarkers in an adult Mexican population environmentally exposed to fluoride and low arsenic levels. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 352:97–106 doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing J, Zheng G, Liu M, Shen X, Zhao F, Wang J, Zhang J, Huang G, Dai P, Chen Y, Chen J, Luo W (2012) Changes in the synaptic structure of hippocampal neurons and impairment of spatial memory in a rat model caused by chronic arsenite exposure. Neurotoxicology 33(5):1230–8 doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandare AL, Gourineni SR, Validandi V (2017) Dental fluorosis, nutritional status, kidney damage, and thyroid function along with bone metabolic indicators in school-going children living in fluoride-affected hilly areas of Doda district, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Environmental monitoring and assessment 189(11):579 doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-6288-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhares D, Camarinho R, Garcia PV, Rodrigues ADS (2018) Mus musculus bone fluoride concentration as a useful biomarker for risk assessment of skeletal fluorosis in volcanic areas. Chemosphere 205:540–544 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wang XY, Zhou XP, Liu ZP, Song XB, Wang ZY, Wang L (2017) Cadmium disrupts autophagic flux by inhibiting cytosolic Ca(2+)-dependent autophagosome-lysosome fusion in primary rat proximal tubular cells. Toxicology 383:13–23 doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Wang ZK, Wang ZY, Yang DB, Liu ZP, Wang L (2016) Mitochondrial permeability transition and its regulatory components are implicated in apoptosis of primary cultures of rat proximal tubular cells exposed to lead. Archives of toxicology 90(5):1193–209 doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1547-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 25(4):402–8 doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Ma Z, Yin S, Yan X, Wang J (2017) Arsenic and fluoride induce apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Chemosphere 167:454–461 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Niu R, Sun Z, Wang J, Luo G, Zhang J, Wang J (2012) Inflammatory responses induced by fluoride and arsenic at toxic concentration in rabbit aorta. Archives of toxicology 86(6):849–56 doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0803-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthari RK, Tikka C, Ommati MM, Niu R, Sun Z, Wang J, Zhang J (2018) Arsenic-Induced Autophagy in the Developing Mouse Cerebellum: Involvement of the Blood-Brain Barrier's Tight-Junction Proteins and the PI3K-Akt-mTOR Signaling Pathway. 66(32):8602–8614 doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Gomez J, Garcia-Vargas GG, Lopez-Carrillo L, Calderon-Aranda ES, Gomez A, Vera E, Valverde M, Cebrian ME, Rojas E (2008) Genotoxic effects of environmental exposure to arsenic and lead on children in region Lagunera, Mexico. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1140:358–67 doi: 10.1196/annals.1454.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Chatterjee S, Flora SJS (2018) Combination therapy with vitamin C and DMSA for arsenic-fluoride co-exposure in rats. Metallomics : integrated biometal science 10(9):1291–1306 doi: 10.1039/c8mt00192h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Mora J, Escobar ML, Rodriguez-Duran L, Massieu L, Montiel T, Rodriguez VM, Hernandez-Mercado K, Gonsebatt ME (2018) Gestational exposure to inorganic arsenic (iAs3+) alters glutamate disposition in the mouse hippocampus and ionotropic glutamate receptor expression leading to memory impairment. 92(3):1037–1048 doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-2111-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Choi J, Biering SB, Dominici E, Williams LE, Hwang S (2016) Targeting by AutophaGy proteins (TAG): Targeting of IFNG-inducible GTPases to membranes by the LC3 conjugation system of autophagy. Autophagy 12(7):1153–67 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1178447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio-Vega R, Gonzalez-Cortes T, Olivas-Calderon E, Lantz RC, Gandolfi AJ, Gonzalez-De Alba C (2015) In utero and early childhood exposure to arsenic decreases lung function in children. Journal of applied toxicology : JAT 35(4):358–66 doi: 10.1002/jat.3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha RA, Gimeno-Alcaniz JV, Martin-Ibanez R, Canals JM, Velez D, Devesa V (2011) Arsenic and fluoride induce neural progenitor cell apoptosis. Toxicology letters 203(3):237–44 doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Jacques N, Brown P, Nauta L, Boxall J, Parker L, Dummer TJB (2018) Estimating the risk of bladder and kidney cancer from exposure to low-levels of arsenic in drinking water, Nova Scotia, Canada. Environment international 110:95–104 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samal AC, Bhattacharya P, Mallick A, Ali MM, Pyne J, Santra SC (2015) A study to investigate fluoride contamination and fluoride exposure dose assessment in lateritic zones of West Bengal, India. Environmental science and pollution research international 22(8):6220–9 doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3817-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkozi K, Horvath E, Vezer T, Papp A, Paulik E (2015) Behavioral and general effects of subacute oral arsenic exposure in rats with and without fluoride. International journal of environmental health research 25(4):418–31 doi: 10.1080/09603123.2014.958138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AH, Marshall G, Liaw J, Yuan Y, Ferreccio C, Steinmaus C (2012) Mortality in young adults following in utero and childhood exposure to arsenic in drinking water. Environmental health perspectives 120(11):1527–31 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song XB, Liu G, Liu F, Yan ZG, Wang ZY, Liu ZP, Wang L (2017) Autophagy blockade and lysosomal membrane permeabilization contribute to lead-induced nephrotoxicity in primary rat proximal tubular cells. Cell death & disease 8(6):e2863 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Feng J, Dong N, Lyu Y, Wei C, Li B, Ma Y, Xie J, Qiu Y, Song G, Ren X, Yan X (2019) Subchronic exposure to arsenite and fluoride from gestation to puberty induces oxidative stress and disrupts ultrastructure in the kidneys of rat offspring. The Science of the total environment 686:1229–1237 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen D, Zhang F, Zhang E, Wang C, Han S, Zheng Y (2013) Arsenic, fluoride and iodine in groundwater of China. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 135:1–21 doi: 10.1016/j.gexplo.2013.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Liu J, He W, Xia T, He P, Chen X, Yang K, Wang A (2007) Dose-effect relationship between drinking water fluoride levels and damage to liver and kidney functions in children. Environmental research 103(1):112–6 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita SI, Kanki T (2017) How autophagy eats large mitochondria: Autophagosome formation coupled with mitochondrial fragmentation. Autophagy 13(5):980–981 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1291113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Dong N, Hao X, Xing Y, Tian X, Feng J, Xie J, Lv Y, Wei C, Gao Y, Qiu Y, Wang T (2019) Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals the Role of the Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway in Fluoride-Induced Cardiotoxicity. 67(17):5033–5042 doi: 10.1021/acsjafc.9b00312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Hao X, Nie Q, Feng C, Wang H, Sun Z, Niu R, Wang J (2015) Effects of fluoride on the ultrastructure and expression of Type I collagen in rat hard tissue. Chemosphere 128:36–41 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Chen Y, Tooze SA (2018) Autophagy pathway: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. 14(2):207–215 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1378838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Xu Y, Yu X, Yang J, Hong F, Zhang A (2019) Silencing GSK3beta instead of DKK1 can inhibit osteogenic differentiation caused by co-exposure to fluoride and arsenic. Bone 123:196–203 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng QB, Xu YY, Yu X, Yang J, Hong F, Zhang AH (2014) Arsenic may be involved in fluoride-induced bone toxicity through PTH/PKA/AP1 signaling pathway. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 37(1):228–33 doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Niu Q, Gao H, Ma R, Lei R, Zhang C, Xia T, Li P, Xu C, Wang C, Chen J, Dong L, Zhao Q, Wang A (2016) Excessive apoptosis and defective autophagy contribute to developmental testicular toxicity induced by fluoride. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987) 212:97–104 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.01.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YY, Yang M, Bao JF, Gu LJ, Yu HL, Yuan WJ (2018) Phosphate stimulates myotube atrophy through autophagy activation: evidence of hyperphosphatemia contributing to skeletal muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. BMC nephrology 19(1):45 doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-0836-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Li Y, Gao Y, Yuan M, Manthari RK, Wang J, Wang J (2018a) TGF-beta1 acts as mediator in fluoride-induced autophagy in the mouse osteoblast cells. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 115:26–33 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.02.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang J, Manthari RK, Wang J (2018b) Fluoride induces apoptosis and autophagy through the IL-17 signaling pathway in mice hepatocytes. Archives of toxicology 92(11):3277–3289 doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2305-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YP, Xi SH, Li MY, Ding TT, Liu N, Cao FY, Zeng Y, Liu XJ, Tong JW, Jiang SF (2017) Fluoride and arsenic exposure affects spatial memory and activates the ERK/CREB signaling pathway in offspring rats. Neurotoxicology 59:56–64 doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.