Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is a relevant topic nowadays, representing one of the main causes of infection-related mortality and morbidity at a global level. This phenomenon is worrisome and represents an area of interest for both clinical practice and fundamental research. One important mechanism whereby bacteria acquire resistance to antibiotics and evade the immune system is by forming biofilms. It is estimated that ~80% of the bacteria producing chronic infections can form biofilms. During the process of biofilm formation microorganisms have the ability to communicate with each other through quorum sensing. Quorum sensing regulates the metabolic activity of planktonic cells, and it can induce microbial biofilm formation and increased virulence. In this review we describe the biofilm formation process, quorum sensing, quorum quenching, several key infectious bacteria producing biofilm, methods of prevention and their challenges and limitations. Although progress has been made in the prevention and treatment of biofilm-driven infections, new strategies are required and have to be further developed.

Keywords: Biofilm formation, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, quorum sensing, biofilm prevention.

SUMMARY

1. Introduction

2. Biofilm-producing bacteria

2.1 Staphylococcus aureus

2.2 Pseudomonas aeruginosa

2.3 Other bacteria

3. Biofilm development, quorum sensing and quorum quenching

4. Prevention of biofilm formation

5. Challenges and Limitations

6. Conclusion

1. Introduction

Bacterial biofilm is produced by ~80% of bacteria responsible for chronic infections and it is an important virulence mechanism, inducing resistance to antimicrobials and evasion from the host’s immune system1. The bacteria producing biofilm comprise a diverse group of organisms, including both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, aerobic and anaerobic, motile and non-motile, just to name a few.

Biofilm has a remarkable complexity and three-dimensional organization2 and forms when biofilm-producing bacteria in an aqueous environment adhere to solid surfaces and produce a network of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), adopting a “multicellular lifestyle”3. These substances include but are not limited to: proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, DNA and form a protective matrix around bacteria, supporting their integrity and survival4. The microorganisms occupy about 10-30% of the biofilm volume. Approximately 97% of the biofilm is water, which is responsible for the flow of nutrients required for bacterial survival within the biofilmsl5,6. Some types of microorganisms first form aggregates of planktonic/free cells in an aqueous environment, as a first step inbiofilm formation7.

Biofilm is a useful adaptation of micro-organisms, enabling them to survive in certain environments4. Generally, microorganisms inside the biofilm are more difficult to eradicate than when present as single cells. This resilience is primarily due to the tolerance mediated by the biofilm-related extracellular network, metabolic dormancy and other potential mechanisms. Genetic factors do not play a major role in this type of resistance, although the close proximity of the cells may also facilitate the transfer of resistance genes8.

Both Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa can be very difficult to eradicate when forming biofilms. Biofilm formation has significant implications and it is a serious problem in a few different fields, including healthcare/clinical care and food industry. In the hospital setting, there are specific bacteria, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and many others which colonize tissue from patients with chronic diseases, implants and/or catheters4. Most device-associated infections are due to microbial biofilm formation. In the food industry, the biofilm and the biofilm-producing bacteria can alter the food quality and compromise food safety. The biofilm can be found inside food recipients such as vats, mixing tanks or utensils used in food preparation9.

Current biofilm control strategies employed in both hospitals and food industry (e.g., cleaning, disinfection, surface preconditioning) are efficient to some extent. However, they are still far from the desired effect and control4, and biofilm-driven infections commonly recur. New strategies for targeting biofilms are thus required. One such strategy is the targeting of the quorum sensing system, which disrupts cell-to-cell communication, conjugation, nutrient acquisition and even motility and production of certain metabolites4.

2. Biofilm-producing bacteria and infections

Based on the National Institute of Health (NIH)’s statistics, biofilm formation is present in about 65% of all bacterial infections and approximately 80% of all chronic infections (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of bacterial species involved in biofilm formation and their biological effects.

| Bacterial strain | Gram stain | Types of infections | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Gram-positive | Chronic biofilm infections, right valve endocarditis, chronic wound infection, lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis | 10-12 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Gram-positive | Endocarditis, catheter-related infection, joint prosthesis infection | 13-15 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Gram-positive | Lung infections, bacterial meningitis, acute or chronic otitis media | 16 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Gram-positive | Co-culture interactions with Pseudomonas, Vibrio strains, listeriosis, contamination of food products | 17,18 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | Gram-negative | Opportunistic infections in patients with blood cancer | 19 |

| Escherichia coli | Gram-negative | Hemolytic uremic syndrome, acute diarrheic syndrome, urinary tract infections | 20 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Gram-negative | Bacteremia, liver abscess, urinary tract infections | 21 |

| Pseudomonas putida | Gram-negative | Urinary tract infection | 22,23 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Gram-negative | Osteomyelitis, ventilator-associated pneumonia, lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, opportunistic infections in neutropenic patients, nosocomial infections | 10 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Gram-negative | Bioremediation, biocontrol- Pythium, Fusarium, antimicrobial properties – production of mupirocin | 17,24-26 |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum | Gram-negative | Biocontrol properties – Pythium | 27 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Gram-positive | Prevention of Salmonella infection | 22,28 |

| Lactococcus lactis | Gram-positive | Antimicrobial properties in the human gastro-intestinal tract | 29 |

Evaluation of the device-related infections resulted in several estimates, including 40% for ventricular-assist devices, 2% for joint prostheses, 4% for mechanical heart valves and 6% for ventricular shunts. Moreover, bacterial colonization of the indwelling devices was associated with infections in 4% of the cases when pacemakers and defibrillators were utilized, but also in 2% of breast implant cases30-32.

Infective valve endocarditis is an infection of the heart which usually occurs as the result of the adherence of bacteria to the endothelium. The most common germs involved in infective endocarditis arestaphylococci and streptococci, members of the HACEK group,Gram-negative bacteria but fungal strains have also been described33. Seeding of the endothelium generally occurs from colonization or infection of different tracts, for example the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tract34, or through direct crossing of the skin barrier either due to wounds or through injecting drug use.

Other types of biofilm-driven infections include chronic wounds, diabetic foot infections, or pulmonary infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, to name only a few.

2.1 Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive coccus that causes infections in certain conditions and is also part of the normal flora of the human body, such as the skin or the nasal mucosa.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is in top two typical hospital-acquired infections in the USA35.

Recently, a staphylococcal aggressiveness score has been defined, based on the presence of three main characteristics: tetrad formation, aggregative adherence and resistance to methicillin. While higher scores are associated with fulminant infection, lower scores are seen in biofilm-drive and relapse-prone infections36.

2.2 Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative rod, facultatively anaerobe, present in a wide range of environments, including a part of the normal human flora, such as the gut flora. It commonly presents resistance towards multiple antibiotics, such as cephalosporins and, potentially, carbapenems, leading to extremely drug-resistant (XDR) infections, where the association of colistin to the antimicrobial regimen generally including a carbapenem such as meropenem may lead to synergic activity37. However, colistin has been associated with neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa’s potential of forming biofilm on medical device surfaces makes it a frequent agent of ventilator-associated pneumonia, or of other device-related infections, for example catheter-associated urinary tract infections38.

2.3 Other bacteria

Many types of bacteria can produce biofilms, and some can also be involved in hospital-acquired infections. Examples include Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Clostridioides difficile and Enterococcus spp38. Other examples of biofilm forming bacteria are presented in Table 1.

3. Biofilm development, quorum sensing and quorum quenching

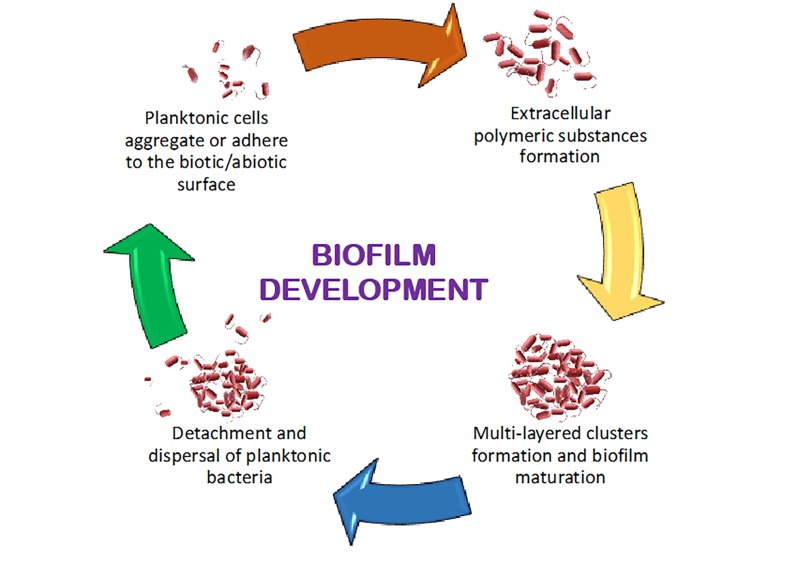

Formation of the biofilm comprises several steps, namely, the attachment, cell-to-cell adhesion, expansion maturation and dispersal (Figure 1)4. Bacterial multiplication leads to the development of microcolonies, which become encapsulated in a layer of hydrogel, that functions as a boundary between the microbial community and the external environment. Table 2 indicates the main characteristics of the biofilm formation phases. Within the bacterial community, cells communicate with each other through quorum sensing (QS) systems, communication based on chemical signal. The role of communication is to modulate cellular functions, population density-based pathogenesis, nutrient acquisition, transfer of genetic material between the cells, motility and synthesis of secondary metabolites. The biofilm matures in parallel with the accumulation of extracellular polymeric substances. The final step involves the detachment of bacterial strains from the microcolonies, potentially leading to the formation of a new biofilm colony in a distinct location38.

Figure 1. Biofilm Development.

Table 2. Particularities of biofilm formation phases.

| Phase | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Adhesion of planktonic cells | Biofilms generally start by the adhesion of microbial cells to a biotic or abiotic surface. Biotic surfaces may include endothelial lesions, necrotic tissues, mucosae, etc., while abiotic surfaces may include indwelling devices: vascular catheters, urinary catheters; prostheses, surfaces from the clinical environment39. This surface adhesion, or primary attachment, can be active or passive depending on microbial factors such as motility, or expression of adhesins. Planktonic strains can move to a specific site and either adhere to an existing lesion/surface, or directly induce tissue necrosis, thereby favoring their subsequent adhesion. Cellular physiology changes, affecting surface membrane proteins. Removal of irreversibly attached cells is difficult as it requires use of specific enzymes, surfactants, sanitizers. Microbial adhesion is also influenced by the physicochemical properties of the biotic or abiotic surface. Bacteria behave as hydrophobic particles presenting negative charge, but this varies with growth phase40. While biofilms have classically been defined as surface-associated microbial cells, a revised definition of biofilms states that the essential characteristic of biofilms is actually inter-bacterial aggregation, which can also be independent of surface adhesion41. |

| Formation of an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix | Genes responsible for adhesion and matrix assembly are activated when stimulated by factors including population density and nutrient limitation. The EPS matrix is composed of a mixture of biopolymers. The matrix produced in broth culture is not similar to the one produced when strains are attached to a surface, and biofilms also differ between in vivo and in vitro conditions. EPS can also be produced by planktonic cells resulting in enhanced attachment42. |

| Accumulation of multi-layered clusters of microbial cells | Microcolony development is the result of simultaneous bacterial aggregation and growth. The tulip biofilm arrangement was established as a discrete model, using confocal laser microscopy43. This discrete model indicates that cells in the outer biofilm layers display active metabolism, while cells deeper inside the biofilm downregulate their metabolism and enter a dormant, persistent state. |

| Biofilm maturation | During biofilm maturation, canals are created in the biofilm structure. These will allow gradient-based passage of nutrients and signaling molecules, favoring organized agglomeration and differentiation of cells based on their metabolic state42. |

| Detachment and dispersal of planktonic bacteria | Following maturation, biofilms become thicker, developing an anaerobic environment on the interior, while external layers may begin separating. Detachment and dispersal can also occur when there is a nutritional imbalance. For instance, low carbon availability increases EPS synthesis44. Detached cells or clusters of cells can travel as septic emboli, and may colonize new sites, then generating infection with potentially new biofilm formation. |

Organic extracellular molecules are produced by the microbial strains within the biofilms and released as both soluble (soluble microbial products (SMPs)) and insoluble materials (organic extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)) in the extracellular media45,46.These substances originate from the substrate metabolism, being microbial byproducts and waste, but also cellular residual content from damaged cells. Insoluble materials or EPS are polysaccharides, extracellular DNA (eDNA) and/or proteins secreted by strains during the establishment and life of biofilms. Yet, most often the difference between the secreted molecules and those composing the microbial biofilm in not obvious6,47,48.

As biofilms have captured the attention of the scientific community, this extensive research field demands new data management and deeper analysis methodologies. The Minimum Information About a Biofilm Experiment (MIABiE) initiative (http://www.miabie.org), brings together an international group of experts, working on the development of guidelines to document bacterial biofilms investigations, as well as the standardization of the current nomenclature, the development and improvement of oriented computational resources and toolsfor deep-understanding, as well as for targeted biofilm research49,50.

Quorum Sensing

Gram-positive bacteria use oligopeptides as signaling molecules to form biofilms, using QS for intraspecies communication. The QS system is a paramount target for the treatment of biofilm associated infections51. There are at least three main types of QS systems to be distinguished: the acyl homoserine lactone QS system (AHL) in Gram-negative bacteria, the autoinducing peptide (AIP) QS system in Gram-positive bacteria and the autoinducer-2 (AI-2) system in both Gram-negative and -positive bacteria52.

Homoserine lactones are a class of important cellular signaling molecules involved in QS and acyl homoserine lactone-dependent QS system is used primarily by Gram-negative bacteria. The AHL molecules have in common the homoserine lactone ring, although they vary in length and substitutes. Remarkably, AHLs are synthesized by a specific cognate AHL synthetase. Interestingly, an increased concentration of AHL was correlated to a significant bacterial growth53.

AIPs are signal molecules secreted by membrane transporters and synthesized by Gram-positive bacteria. As the environmental concentration of AIPs increases, these AIPs bind to the histidine kinase sensor, which phosphorylates, and as a consequence alters target gene expression. In Staphylococcus aureus quorum sensing signals are stringently regulated by the accessory gene regulator or agr which is associated with AIPs secretion. These genes are responsible for the production of numerous toxins and degradable exoenzymes.

As part of their cooperation and communication, microorganisms have the ability to sense and translate the signals from distinct strains in AI-2 or autoinducer-2 interspecific signals, catalyzed by LuxS synthase. Moreover, LuxS is involved in the activation of the methylation cycle, being demonstrated to control the expressions of hundreds of genes associated with the microbial processes of surface adhesion, detachment, and toxin production54.

4. Prevention of biofilm formation

Both in healthcare and the food industry, the main strategy to tackle bacterial biofilms is to prevent their development. In order to do this, there are several ways (e.g., cleaning, sterilization) of preventing bacteria from reaching or proliferating in critical locations. In many cases, especially in food processing, sterility of the environment is not entirely possible and is not cost-effective. Measured taken involve thermal, chemical or mechanical strategies for bacterial biofilm prevention.

However, even with the best existing prevention measures adopted, biofilm may form and biofilm-producing bacteria could potentially be a problem. Thus, efficient diagnosis and treatment of biofilm-related infections is important in clinical settings. Several recommendations and guidelines exist and we recommend the summary presented Kamaruzzaman NF et al38. For example, the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases provides guidelines for the diagnosis of these infections, which implies both laboratory and clinical diagnosis methods55.

5. Challenges and Limitations

Despite important advances in our current knowledge on biofilm-producing bacteria and the organization and function of the biofilm itself, significant research remains to be performed. This is in part due to the prior focus on the investigation of planktonic bacteria, not on the biofilm formation4. Together with this adaptation of the research focus, new methods (imagistic or molecular) are now available and under development for the investigation of biofilms and their components. Moreover, in silico methods may be a good solution in solving medical or technological challenges related to biofilm formation, prevention or treatment. Such methods comprise the biofilm consortia metabolic models, designed for the prediction of biofilm formation stages based on the components and their concentration or the molecular docking software for designing and predicting the efficiency of new drugs56,57.

New prevention and treatment strategies have to be further developed. Table 3 summarizes the main mechanisms of resistance to antibiotics. The ability of biofilm-forming bacteria to adapt to the human environment is also related to immune system evasion. Bacteria from the biofilm can avoid recognition by immune system and avoid phagocytosis. Biofilm can obscure recognition of bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides, lipoproteins and nucleic acids. Neutrophils migrate towards the biofilm produced by bacteria, such as S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. However, decreased phagocytosis and bacterial cell killing is observed upon this migration. Interestingly, the glycolipids implicated in quorum sensing by P. aeruginosa can induce necrosis of neutrophils and disruption of this process by using quorum sensing inhibitors promotes phagocytosis. Thus, new biofilm targeting treatments addressing evasion from the immune system can be developed38.

Table 3. Mechanism of biofilm-mediated antimicrobial resistance.

| Resistance mechanism | Characteristics | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Glycocalyx | The capsule can be found in Gram-positive as well as in Gram-negative bacteria, being an integral part of the biofilm. The contribution to the maturation step is possible due to electrostatic and hydrogen bonds established between the matrix and the abiotic surface. Its composition in glycoprotein and polysaccharides varies with biofilm development, supporting pathogens to survive in adverse conditions. The antibiotic bacterial resistance and different units of antimicrobials are supported by the glycocalyx. The external layer acquires antimicrobial compounds, serving as well as adherent for exoenzymes and protecting against antibacterial activity by providing a substrate for biocides degradation. | 6,59 |

| Enzyme-mediated resistance | Enzymatic reduction of ionic particles mediates the transformation of toxic into nontoxic molecules. The existence of heavy metals, such as cadmium, nickel, silver, zinc, copper, cobalt, induces a large diversity of resistant phenotypes. | 60 |

| Metabolism and growth rate heterogeneity | Bacterial metabolic activity and growth rate are influenced by the heterogeneities in nutrients and the variable oxygen concentration within biofilms, having strong influence on the quantity of both metabolic substrates and products, especially at the peripheral area, where microbial proliferation is supported. Limited metabolic activity inside the biofilm results in slowly growing strains inside the matrix. The changes in cell growth cycle affect the enzymatic process inside biofilms, influencing both metabolic and growth rate variations. Moreover, microbial communities increase the level of antibiotic resistance by expressing certain genes under anaerobic conditions. | 61,62 |

| Cellular persistence | Persistent strains are responsible for the infections’ chronicity as they become tolerant to antibacterial agents. Biofilms contain persistent cells, which elicit multidrug tolerance. The glycocalyx improves the ability to protect the immune system, as they re-induce growth of bacterial biofilm and compete for the antibiotic targets and for multidrug resistance (MDR) protein synthesis. | 63-65 |

| Metabolic state | Nutrients’ limited availability affects the composition and modifies the prokaryotic envelope. After being exposed to inhibitory concentration of bactericidal agents, the resistant cell population shows phenotypic adaptation. Treating biofilms with antimicrobial agents conducts to loss of their respiratory activity. | 66,67 |

| Genetic profile | The multiple antibiotic resistance also known as mar operons are general regulators involved in control of various genes' expression in E. coli, supporting the MDR phenotype. Stress response cells show increased resistance to a damaging factor within hours of exposure. Diverse regulatory genes, for instance oxyR and soxR, were demonstrated to determine intracellular redox potential and activation of stress response when bacterial strains are exposed to molecular oxidizers. | 68,69 |

| Quorum sensing (QS) | QS influences the heterogeneous structure, as in convenient nutrient supply and suitable environment, the phenotype is essential in the cell migration process. QS deficiency was associated with thinner microbial biofilm development and, as a consequence, lower EPS production. | 70,71 |

| Stress response | The stress response acts as a preventive factor for cell damage more than repair. Starvation, decreased or increased temperature, high osmolality and low pH are seen as causes of stress induction. Altered gene expression due to the stress response in immobilized strains result in increased resistance to biocides. | 72-74 |

| External membrane structure | While most antibacterial agents must penetrate bacterial cells to target a specific site, modification of cellular membrane may control antibiotic resistance. The lipopolysaccharide layer prevents hydrophilic antimicrobials from entering through the outer membrane while the external membrane proteins reject hydrophobic molecules. | 75,76 |

| Efflux systems | Efflux pumps facilitate bacterial survival under extreme environmental conditions by exerting both intrinsic and acquired resistance to different antimicrobials, from the same or different families. Consequently, the overproduction of efflux pumps determines multidrug resistance, when combined with similar resistance mechanisms, for example antibiotic inactivation or target adjustment. The efflux pumps are seen as a major player in the MDR of Gram-negative bacteria because of the deep understanding of efflux pumps mechanisms which could provide drug discovery platforms in targeted bacterial pathogens. | 77-81 |

An important limitation in biofilm prevention, treatment and investigation is its physiological heterogeneity. Although individual cells can be isolated and investigated from the biofilm, the spatial relation, structure and properties are not preserved50. Thus, it is imperative to use techniques which preserve the spatial relationships between cells. The characteristics and physiology of bacterial cells from the biofilm can significantly differ based on their localization within the biofilm. This is not only important in investigation of the biofilm, e.g., -omic profiling resulting in average results for a diverse biofilm population but can also contribute to biofilm resistance to preventive and treatment measures50.

However, although many of the biofilms are regarded as harmful to humans, biofilms can also play a useful role, contributing for example to the genetic and natural diversity through cell to cell interactions within the biofilm, of protecting different organisms (e.g., marine algae) against pathogens58.

Control of the formation of biofilms that have negative effects on human health remains a challenge, with few treatment options clinically available.

6. Conclusion

Biofilms enable bacteria to survive in specific environments, confer resistance or tolerance to treatment and the capacity to evade the host immune system. They represent a challenge in prevention and treatment of infections. Biofilms also confer to bacteria the property to resist standard cleaning procedures in the food industry. Thus, it is important to better understand how it can be prevented and managed and to develop effective targeted therapies.

Investigation of biofilm’s complex 3D structure, function, development, maturation and all characteristics of involved cells (proteomic, genomic data) is required for a better understanding of these processes. Attacking the biofilm should take into consideration not only targeting the bacteria inside the biofilm but also its extracellular components. Drug design, delivery and in silico methods can be used to predict or measure the efficacy of anti-microbial drugs when biofilm is present.

New anti-biofilm strategies are required and have to be further developed. These new treatments have to present high specificity, low toxicity on normal eukaryotic cells and host microbiota and be efficient in treating infection caused by the biofilm-causing organisms.

KEY POINTS

◊ Approximately 80% of the bacteria producing chronic infections can form biofilms, inducing resistance to antibiotics and immune system evasion

◊ Quorum sensing regulates the metabolic activity of planktonic cells, and it can induce microbial biofilm formation and increased virulence

◊ New strategies are required in order to target the biofilm and biofilm-producing bacteria

Acknowledgments

This review was developed in support of the Bachelor thesis “Pyrazole-benzimidazole derivatives with inhibitory activity on bacterial biofilm and cytotoxic assessment” of Ms. Veronica Georgiana Preda at the University of Bucharest (supervised by Dr. Christina Marie Zălaru) in partnership with the Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania (supervised by Dr. Oana Săndulescu). We thank University of Bucharest for support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

National Institute of Health (NIH); soluble microbial products (SMPs); Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS); Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella (HACEK); extremely-drug resistant (XDR); methiciling-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; quorum sensing (QS); Minimum Information About a Biofilm Experiment (MIABiE); environmental DNA (eDNA).

DISCOVERIES is a peer-reviewed, open access, online, multidisciplinary and integrative journal, publishing high impact and innovative manuscripts from all areas related to MEDICINE, BIOLOGY and CHEMISTRY

References

- 1.Targeting microbial biofilms: current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Koo Hyun, Allan Raymond N., Howlin Robert P., Stoodley Paul, Hall-Stoodley Luanne. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2017;15(12):740-755. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The biogeography of polymicrobial infection. Stacy Apollo, McNally Luke, Darch Sophie E., Brown Sam P., Whiteley Marvin. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2015;14(2):93-105. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacterial solutions to multicellularity: a tale of biofilms, filaments and fruiting bodies. Claessen Dennis, Rozen Daniel E., Kuipers Oscar P., Søgaard-Andersen Lotte, van Wezel Gilles P. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2014;12(2):115-124. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Weapons to Fight Old Enemies: Novel Strategies for the (Bio)control of Bacterial Biofilms in the Food Industry. Coughlan Laura M., Cotter Paul D., Hill Colin, Alvarez-Ordóñez Avelino. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dispersing biofilms with engineered enzymatic bacteriophage. Lu T. K., Collins J. J. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(27):11197-11202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704624104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The biofilm matrix – an immobilized but dynamic microbial environment. Sutherland I. Trends in Microbiology. 2001;9(5):222-227. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaping the Growth Behaviour of Biofilms Initiated from Bacterial Aggregates. Melaugh Gavin, Hutchison Jaime, Kragh Kasper Nørskov, Irie Yasuhiko, Roberts Aled, Bjarnsholt Thomas, Diggle Stephen P., Gordon Vernita D., Allen Rosalind J. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0149683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Flemming Hans-Curt, Wingender Jost, Szewzyk Ulrich, Steinberg Peter, Rice Scott A., Kjelleberg Staffan. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2016;14(9):563-575. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Stewart Philip S, William Costerton J. The Lancet. 2001;358(9276):135-138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modulation of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilm: an in vitro study with new coumarin derivatives. Das Tapas, Das Manash C., Das Antu, Bhowmik Sukhen, Sandhu Padmani, Akhter Yusuf, Bhattacharjee Surajit, De Utpal Ch. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2018;34(11) doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevention and treatment ofStaphylococcus aureusbiofilms. Bhattacharya Mohini, Wozniak Daniel J, Stoodley Paul, Hall-Stoodley Luanne. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2015;13(12):1499-1516. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1100533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staphylococcus aureusbiofilm: a complex developmental organism. Moormeier Derek E., Bayles Kenneth W. Molecular Microbiology. 2017;104(3):365-376. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Native valve staphylococcus epidermidis endocarditis: report of seven cases and review of the literature. Arber Nadir, Militianu Arie, Ben-Yehuda Arie, Krivoy Norberto, Plnkhas Jack, Sidi Yechezkel. The American Journal of Medicine. 1991;90(6):758-762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.In-host evolution of Staphylococcus epidermidis in a pacemaker-associated endocarditis resulting in increased antibiotic tolerance. Dengler Haunreiter Vanina, Boumasmoud Mathilde, Häffner Nicola, Wipfli Dennis, Leimer Nadja, Rachmühl Carole, Kühnert Denise, Achermann Yvonne, Zbinden Reinhard, Benussi Stefano, Vulin Clement, Zinkernagel Annelies S. Nature Communications. 2019;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deciphering Genomic Virulence Traits of a Staphylococcus epidermidis Strain Causing Native-Valve Endocarditis. Fournier P.-E., Gouriet F., Gimenez G., Robert C., Raoult D. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013;51(5):1617-1621. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02820-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary tract infection in pedeatrics. Pougnet Richard, Sapin Jeanne, De Parscau Loïc, Pougnet Laurence. Annales de biologie clinique. 2017;75(3):348-350. doi: 10.1684/abc.2017.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Listeria monocytogenes Impact on Mature or Old Pseudomonas fluorescens Biofilms During Growth at 4 and 20°C. Puga Carmen H., Orgaz Belen, SanJose Carmen. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella spp. in Seafood Products Using Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction. Zarei Mehdi, Maktabi Siavash, Ghorbanpour Masoud. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2012;9(2):108-112. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.OUTBREAK OF BURKHOLDERIA CEPACIA INFECTION: A SYSTEMATIC STUDY IN A HEMATOLOGY-ONCOLOGY UNIT OF A TERTIARY CARE HOSPITAL FROM EASTERN INDIA. Baul Shuvra Neel, De Rajib, MANDAL PRAKAS KUMAR, Roy Swagnik, Dolai Tuphan Kanti, Chakrabarti Prantar. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2018;10(1):e2018051. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2018.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Identificación de Escherichia coli enteropatógena en niños con síndrome diarreico agudo del Estado Sucre, Venezuela. Michelli Elvia, Millán Adriana, Rodulfo Hectorina, Michelli Mirian, Luiggi Jesús, Carreño Numirin, De Donato Marcos. Biomédica. 2016;36 doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v36i0.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infection Complicated by Endophthalmitis, Perinephric Abscess, and Ecthyma Gangrenosum. STOTKA JENNIFER L., RUPP MARK E. Southern Medical Journal. 1991;84(6):790-792. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199106000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nosocomial Pseudomonas putida Bacteremia: High Rates of Carbapenem Resistance and Mortality. Kim SE, Park SH, Park HB, Park KH, Kim SH, Jung SI, Shin JH, Jang HC, Kang SJ. Chonnam Med J. 2012;48(2):91–95. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2012.48.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PSEUDOMONAS SPECIES CAUSING URINARY TRACT INFECTION AND ITS ANTIBIOGRAM AT A TERTIARY CARE HOSPITAL. Kl Shobha, L Ramachandra, Rao Amita Shobha, Km Anand, S Gowrish Rao. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2017;10(11):50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biocontrol of Pythium in the pea rhizosphere by antifungal metabolite producing and non-producing Pseudomonas strains. Naseby D.C., Way J.A., Bainton N.J., Lynch J.M. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2001;90(3):421-429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Investigating the formulation of alginate- gelatin encapsulated Pseudomonas fluorescens (VUPF5 and T17-4 strains) for controlling Fusarium solani on potato. Pour Mojde Moradi, Saberi-Riseh Roohallah, Mohammadinejad Reza, Hosseini Ahmad. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019;133:603-613. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antimicrobial properties of Pseudomonas strains producing the antibiotic mupirocin. Matthijs Sandra, Vander Wauven Corinne, Cornu Bertrand, Ye Lumeng, Cornelis Pierre, Thomas Christopher M., Ongena Marc. Research in Microbiology. 2014;165(8):695-704. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Effect of Seed Treatment with Rhizobium leguminosarum on Pythium Damping-off, Seedling Height, Root Nodulation, Root Biomass, Shoot Biomass, and Seed Yield of Pea and Lentil. Huang H. C., Erickson R. S. Journal of Phytopathology. 2007;155(1):31-37. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Probiotic bacteria prevent Salmonella – induced suppression of lymphoproliferation in mice by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Wagner R. Doug, Johnson Shemedia J. BMC Microbiology. 2017;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-0990-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A review on Lactococcus lactis: from food to factory. Song Adelene Ai-Lian, In Lionel L. A., Lim Swee Hua Erin, Rahim Raha Abdul. Microbial Cell Factories. 2017;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0669-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. Jamal Muhsin, Ahmad Wisal, Andleeb Saadia, Jalil Fazal, Imran Muhammad, Nawaz Muhammad Asif, Hussain Tahir, Ali Muhammad, Rafiq Muhammad, Kamil Muhammad Atif. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2018;81(1):7-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Consequences of Biofilm Dispersal on the Host. Fleming Derek, Rumbaugh Kendra. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treatment of Infections Associated with Surgical Implants. Darouiche Rabih O. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(14):1422-1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fungal Endocarditis: Evidence in the World Literature, 1965-1995. Ellis M. E., Al-Abdely H., Sandridge A., Greer W., Ventura W. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32(1):50-62. doi: 10.1086/317550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biofilms: Survival Mechanisms of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. Donlan R. M., Costerton J. W. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2002;15(2):167-193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hospitalizations and Deaths Caused by Methicillin-ResistantStaphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999–2005. Klein Eili, Smith David L., Laxminarayan Ramanan. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(12):1840-1846. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comparative evaluation of aggressiveness traits in staphylococcal strains from severe infections versus nasopharyngeal carriage. Săndulescu Oana, Bleotu Coralia, Matei Lilia, Streinu-Cercel Anca, Oprea Mihaela, Drăgulescu Elena Carmina, Chifiriuc Mariana Carmen, Rafila Alexandru, Pirici Daniel, Tălăpan Daniela, Dorobăţ Olga Mihaela, Neguţ Alina Cristina, Oţelea Dan, Berciu Ioana, Ion Daniela Adriana, Codiţă Irina, Calistru Petre Iacob, Streinu-Cercel Adrian. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2017;102:45-53. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colistin in the management of severe infections with multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacilli. Streinu-Cercel Adrian. GERMS. 2014;4(1):7-8. doi: 10.11599/germs.2014.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Targeting the Bacterial Protective Armour; Challenges and Novel Strategies in the Treatment of Microbial Biofilm. Kamaruzzaman Nor, Tan Li, Mat Yazid Khairun, Saeed Shamsaldeen, Hamdan Ruhil, Choong Siew, Wong Weng, Chivu Alexandru, Gibson Amanda. Materials. 2018;11(9):1705. doi: 10.3390/ma11091705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Managing sticky situations – anti-biofilm agents. Săndulescu Oana. GERMS. 2016;6(2):49-49. doi: 10.11599/germs.2016.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Processes of bioadhesion on stainless steel surfaces and cleanability: A review with special reference to the food industry. Boulané‐Petermann Laurence. Biofouling. 1996;10(4):275-300. doi: 10.1080/08927019609386287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The in vivo biofilm. Bjarnsholt Thomas, Alhede Maria, Alhede Morten, Eickhardt-Sørensen Steffen R, Moser Claus, Kühl Michael. Trends in Microbiology. 2013;21(9):466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biofilm Formation and Control in Food Processing Facilities. Chmielewski R.A.N., Frank J.F. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2003;2(1):22-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heterogeneity in biofilms. Wimpenny Julian, Manz Werner, Szewzyk Ulrich. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2000;24(5):661-671. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Effect of Nutrients on Biofilm Formation by Listeria monocytogenes on Stainless Steel. KIM KWANG Y., FRANK JOSEPH F. Journal of Food Protection. 1995;58(1):24-28. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soluble microbial products formation in anaerobic chemostats in the presence of toxic compounds. Aquino S.F., Stuckey D.C. Water Research. 2004;38(2):255-266. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Integrated model of the production of soluble microbial products (SMP) and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in anaerobic chemostats during transient conditions. Aquino Sérgio F., Stuckey David C. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2008;38(2):138-146. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Role of eDNA on the Adhesion Forces betweenStreptococcus mutansand Substratum Surfaces: Influence of Ionic Strength and Substratum Hydrophobicity. Das Theerthankar, Sharma Prashant K., Krom Bastiaan P., van der Mei Henny C., Busscher Henk J. Langmuir. 2011;27(16):10113-10118. doi: 10.1021/la202013m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Exopolysaccharides in biofilms, flocs and related structures. Sutherland I. W. Water Science and Technology. 2001;43(6):77-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minimum information about a biofilm experiment (MIABiE): standards for reporting experiments and data on sessile microbial communities living at interfaces. Lourenço Anália, Coenye Tom, Goeres Darla M., Donelli Gianfranco, Azevedo Andreia S., Ceri Howard, Coelho Filipa L., Flemming Hans-Curt, Juhna Talis, Lopes Susana P., Oliveira Rosário, Oliver Antonio, Shirtliff Mark E., Sousa Ana M., Stoodley Paul, Pereira Maria Olivia, Azevedo Nuno F. Pathogens and Disease. 2014;70(3):250-256. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Critical review on biofilm methods. Azeredo Joana, Azevedo Nuno F., Briandet Romain, Cerca Nuno, Coenye Tom, Costa Ana Rita, Desvaux Mickaël, Di Bonaventura Giovanni, Hébraud Michel, Jaglic Zoran, Kačániová Miroslava, Knøchel Susanne, Lourenço Anália, Mergulhão Filipe, Meyer Rikke Louise, Nychas George, Simões Manuel, Tresse Odile, Sternberg Claus. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2016;43(3):313-351. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1208146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baicalein Inhibits Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation and the Quorum Sensing System In Vitro. Chen Yan, Liu Tangjuan, Wang Ke, Hou Changchun, Cai Shuangqi, Huang Yingying, Du Zhongye, Huang Hong, Kong Jinliang, Chen Yiqiang. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0153468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quorum Sensing Inhibitors as Anti-Biofilm Agents. Brackman Gilles, Coenye Tom. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2014;21(1):5-11. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140905114627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quorum sensing: How bacteria can coordinate activity and synchronize their response to external signals? Li Zhi, Nair Satish K. Protein Science. 2012;21(10):1403-1417. doi: 10.1002/pro.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quorum Sensing: A Prospective Therapeutic Target for Bacterial Diseases. Jiang Qian, Chen Jiashun, Yang Chengbo, Yin Yulong, Yao Kang. BioMed Research International. 2019;2019:1-15. doi: 10.1155/2019/2015978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ESCMID∗ guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of biofilm infections 2014. Høiby N., Bjarnsholt T., Moser C., Bassi G.L., Coenye T., Donelli G., Hall-Stoodley L., Holá V., Imbert C., Kirketerp-Møller K., Lebeaux D., Oliver A., Ullmann A.J., Williams C. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2015;21:S1-S25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.In Silico Analysis of the Quorum Sensing Metagenome in Environmental Biofilm Samples. Barriuso Jorge, Martínez María J. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prediction of Biofilm Inhibiting Peptides: An In silico Approach. Gupta Sudheer, Sharma Ashok K., Jaiswal Shubham K., Sharma Vineet K. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The Second Skin: Ecological Role of Epibiotic Biofilms on Marine Organisms. Wahl Martin, Goecke Franz, Labes Antje, Dobretsov Sergey, Weinberger Florian. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Potential effect of cationic liposomes on interactions with oral bacterial cells and biofilms. Sugano Marika, Morisaki Hirobumi, Negishi Yoichi, Endo-Takahashi Yoko, Kuwata Hirotaka, Miyazaki Takashi, Yamamoto Matsuo. Journal of Liposome Research. 2015:1-7. doi: 10.3109/08982104.2015.1063648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plasmid-mediated formaldehyde resistance in Escherichia coli: characterization of resistance gene. Kümmerle N, Feucht H H, Kaulfers P M. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1996;40(10):2276-2279. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spatial Variations in Growth Rate within Klebsiella pneumoniae Colonies and Biofilm. Wentland E.J., Stewart P.S., Huang C.-T., McFeters G.A. Biotechnology Progress. 1996;12(3):316-321. doi: 10.1021/bp9600243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diffusion in Biofilms. Stewart P. S. Journal of Bacteriology. 2003;185(5):1485-1491. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1485-1491.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Persister cells and the riddle of biofilm survival. Lewis K. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2005;70(2):267-274. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Lewis Kim. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2006;5(1):48-56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bacterial Walls, Peptidoglycan Hydrolases, Autolysins, and Autolysis. SHOCKMAN G.D., DANEO-MOORE L., KARIYAMA R., MASSIDDA O. Microbial Drug Resistance. 1996;2(1):95-98. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Farr S B, Kogoma T. Microbiological Reviews. 1991;55(4):561-585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.An evaluation of the potential of the multiple antibiotic resistance operon (mar) and the multidrug efflux pump acrAB to moderate resistance towards ciprofloxacin in Escherichia coli biofilms. Maira-Litran T., Allison D. G., Gilbert P. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2000;45(6):789-795. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Look who's talking: communication and quorum sensing in the bacterial world. Williams Paul, Winzer Klaus, Chan Weng C, Cámara Miguel. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;362(1483):1119-1134. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quorum sensing in streptococcal biofilm formation. Suntharalingam Prashanth, Cvitkovitch Dennis G. Trends in Microbiology. 2005;13(1):3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase genes and mediates biofilm susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide. Hassett Daniel J., Ma Ju-Fang, Elkins James G., McDermott Timothy R., Ochsner Urs A., West Susan E. H., Huang Ching-Tsan, Fredericks Jessie, Burnett Scott, Stewart Philip S., McFeters Gordon, Passador Luciano, Iglewski Barbara H. Molecular Microbiology. 1999;34(5):1082-1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Effects of quorum-sensing deficiency on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Shih P.-C. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2002;49(2):309-314. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gene expression and protein levels of the stationary phase sigma factor, RpoS, in continuously-fed Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Xu Karen D., Franklin Michael J., Park Chul-Ho, McFeters Gordon A., Stewart Philip S. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2001;199(1):67-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Unexplored reservoirs of pathogenic bacteria: protozoa and biofilms. Brown M. Trends in Microbiology. 1999;7(1):46-50. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Drenkard Eliana. Microbes and Infection. 2003;5(13):1213-1219. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Transport across the outer membrane porin of mycolic acid containing actinomycetales: Nocardia farcinica. Singh Pratik Raj, Bajaj Harsha, Benz Roland, Winterhalter Mathias, Mahendran Kozhinjampara R. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2015;1848(2):654-661. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Resistance ofPseudomonas aeruginosato isothiazolone. Brözel V.S., Cloete T.E. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1994;76(6):576-582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Why are bacteria refractory to antimicrobials? Hogan D. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2002;5(5):472-477. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: roles of integrons, efflux pumps, phosphoglucomutase (SpgM), and melanin and biofilm formation. Liaw S.-J., Lee Y.-L., Hsueh P.-R. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2010;35(2):126-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Membrane Permeability and Regulation of Drug “Influx and Efflux” in Enterobacterial Pathogens. Davin-Regli Anne, Bolla Jean-Michel, James Chloe, Lavigne Jean-Philippe, Chevalier Jacqueline, Garnotel Eric, Molitor Alexander, Pages Jean-Marie. Current Drug Targets. 2008;9(9):750-759. doi: 10.2174/138945008785747824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strategies for bypassing the membrane barrier in multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Bolla Jean-Michel, Alibert-Franco Sandrine, Handzlik Jadwiga, Chevalier Jacqueline, Mahamoud Abdallah, Boyer Gérard, Kieć-Kononowicz Katarzyna, Pagès Jean-Marie. FEBS Letters. 2011;585(11):1682-1690. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Expression Patterns and Contribution to Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. De Kievit T. R., Parkins M. D., Gillis R. J., Srikumar R., Ceri H., Poole K., Iglewski B. H., Storey D. G. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2001;45(6):1761-1770. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1761-1770.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]