Abstract

Rationale: Chemodynamic therapy (CDT) based on the Fe(II)-mediated Fenton reaction is an emerging tumor treatment strategy. However, the catalytic efficiency in tumors is crucially limited by Fe(II). Herein, an endogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation and photothermal synergistically enhanced CDT strategy based on ellagic acid-Fe-bovine serum albumin (EA-Fe@BSA) nanoparticles (NPs) was developed for colon tumor inhibition. On the one hand, the Fe(III) with low catalytic activity in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs could be rapidly reduced to the highly active Fe(II) by the abundant H2S in colon cancer tissues. Thus, a rapid Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion system was established, wherein highly active Fe(II) ions were continuously regenerated to improve the CDT efficiency. On the other hand, the photothermal effect of EA-Fe@BSA NPs also accelerated the production of hydroxyl radicals (•OH), thereby synergistically enhancing the CDT performance and improving the therapeutic efficacy.

Methods: The endogenous H2S accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion and PTT enhanced CDT were investigated by characterization of the Fe valence state and detection of •OH. T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was tested both in vitro and in vivo. The biocompatibility of NPs were examined via MTT assay, hemolysis analysis and routine blood measurements. The enhanced CDT was investigated in HCT116 colon cancer cells by Calcein-AM/PI staining and MTT assay, and tumor inhibition was demonstrated in HCT116 tumor bearing mice.

Results: In this work, EA-Fe@BSA NPs were constructed as a CDT theranostic reagent. The H2S accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion was confirmed, more degradation of MB and generation of •OH demonstrated the enhanced CDT in vitro. EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibited good T1-weighted MRI performance. More importantly, it displayed strong near-infrared (NIR) absorption and excellent photothermal efficiency, further promotes the production of •OH. Hence, the efficacy of CDT was enhanced, and the tumor growth was inhibited efficiently.

Conclusion: All results demonstrate that this strategy based on endogenous H2S promoted Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation together with PTT acceleration permits efficient Fenton-reaction- mediated CDT both in vitro and in vivo, which holds great potential for effective colon cancer theranostics.

Keywords: endogenous H2S, Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation, photothermal therapy, chemodynamic therapy, colon cancer treatment

Introduction

Colon cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide. Its early symptoms are not obvious, but systemic symptoms such as anemia and weight loss occur in the terminal stage 1,2. Both its morbidity and mortality are very high. By far the most common clinical diagnosis and treatment strategies for colon cancer are colonoscopy, surgery, and radiation therapy. However, there are huge risks of recurrence and metastasis, accompanied by great pain. Hence, it is imperative to develop more effective minimally invasive approaches for diagnosing and treating colon cancer. Interestingly, it is well known that the enzyme cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) can produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and is selectively up-regulates in colon cancer cells, thus, the concentration of H2S in colon cancer tissues (0.3-3.4 mmol L-1) is considerably higher than that in non-tumor tissues 3-7. Taking advantage of this property, in our previous work, we designed Cu2O nanoparticles (NPs) for colon cancer theranostics, which could react with H2S to afford CuS with high absorption in the near-infrared (NIR) region for photothermal therapy (PTT). Nevertheless, the concentrations of Cu2O and H2S required for good treatment effects were both extremely high, which hindered its further application 8. Thus, it is crucial to explore more effective approaches and develop novel intelligent agents for the treatment of colon cancer.

An emerging strategy in recent years is chemodynamic therapy (CDT), in which endogenous H2O2 is converted to hydroxyl radicals (•OH) via metal-ion-catalyzed Fenton or Fenton-like reactions at the tumor site 9. The •OH (E(•OH/H2O) = 2.80 V) is highly toxic and a more oxidizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) than H2O2 (E(H2O2/H2O) = 1.78 V), therefore causing harmful oxidative damage to tumors 10-15. The efficiency of CDT is dependent on the H2O2 concentration, pH, and metal catalyst, and substantial efforts have been devoted to designing CDT nanotheranostic agents with high catalytic performance, in which the Fe(II)-initiated Fenton reaction has been the most widely applied. In the Fe(II)-catalyzed system, Fe(II) catalyzes the conversion of H2O2 to •OH and is itself converted to Fe(III), which subsequently mediate Fe(III)-catalyzed Fenton-like reactions with lower catalytic activity. Meanwhile, the rate of Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation is slow (0.002-0.01 M-1 s-1), which greatly limits the rate of the Fenton reaction and thus hinders the further application of CDT 16-22. To date, several strategies have been proposed for enhancing CDT performance, including thermal acceleration, PTT enhancement, valence state conversion, and self-supplied H2O2 23-30. For Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion, one of the most common approaches is introducing a reducing agent or semiconductor to Fe materials to catalyze the regeneration of Fe(II), but this strategy often requires light excitation, additional reagents, or complex protocols 31-33. Thus, it is pressing to propose a facile method for Fe(III)/Fe(II) rapid conversion. Another strategy to enhance CDT performance is increasing the temperature at the tumor site. PTT, in which the absorbed NIR laser energy generates local thermal effects for tumor treatment, has attracted considerable attention owing to its low cost, minimal invasiveness, and tumor specificity 34-37. Importantly, the heating effect of PTT could accelerate the production of •OH, thus enhancing the CDT efficiency and providing more effective treatment 38-41. Therefore, the development of a CDT reagent with high catalytic activity based on Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion and PTT would be of great value.

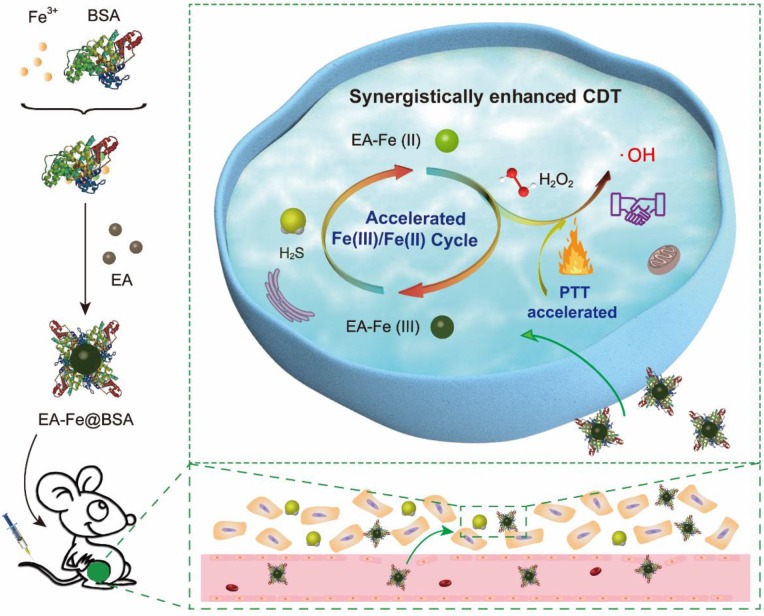

As a proof of concept, ultra-small ellagic acid-Fe-bovine serum albumin (EA-Fe@BSA) NPs were constructed as a CDT reagent to demonstrate the Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion and PTT enhanced CDT. The EA-Fe@BSA NPs with good biocompatibility was prepared via a simple assembly of natural polyphenol, Fe(III) and albumin for endogenous H2S and PTT accelerated CDT efficacy (Scheme 1). The key feature of this approach is acceleration of the Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation to regenerate highly active Fe(II) via the strong reducing ability of endogenous H2S in colon cancer tissues. Following the intravenous injection of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs into mice and their internalization by colon cancer tumors, the Fe(III) with low catalytic activity in the synthesized EA-Fe@BSA NPs was rapidly reduced to the active Fe(II) by the abundant endogenous H2S, thereby providing a rapid Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation system for improved CDT. Furthermore, the obtained EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibited strong NIR absorption and excellent thermal effects, thereby synergistically improving the CDT efficiency. Moreover, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs showed obvious T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) both in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating their potential application in colon tumor diagnosis and treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that endogenous H2S has been utilized as a reducing agent to promote CDT efficacy for colon cancer treatment. Therefore, the developed strategy is expected to prove valuable for colon cancer treatment, which was confirmed by prominent tumor inhibition in HCT116 colon cancer tumor-bearing mice.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs and endogenous H2S accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion and PTT synergistically enhanced CDT.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of EA-Fe@BSA NPs

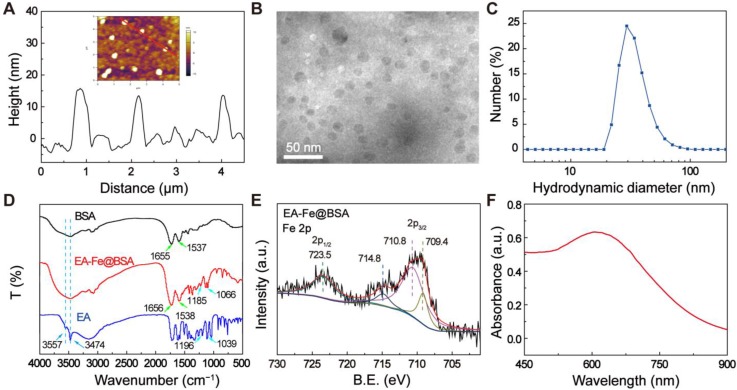

The EA-Fe@BSA NPs were synthesized at room temperature as follows. Aqueous FeCl3 solution was added to BSA solution, followed by the addition of EA under stirring to form a dark blue solution. The EA-Fe@BSA NPs were isolated by ultrafiltration centrifugation. The size and morphology of the as-synthesized NPs were characterized via atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Figure 1A). The prepared NPs exhibited a monodisperse spherical morphology with an average diameter of 14.41 ± 0.08 nm (Figure S1). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) further confirmed that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs (Figure 1B) were monodisperse spheres with a diameter of 13.84 ± 2.53 nm (Figure S2), in accordance with the AFM results. In addition, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs displayed an average hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 29.2 nm (Figure 1C). The hydrodynamic diameter was slightly larger than the diameter measured by AFM and TEM, which was attributed to the hydration shells and strongly hydrophilic BSA. More importantly, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibit excellent dispersibility and stability in different medium including water, PBS and plasma (Figure S3 and S4).

Figure 1.

Characterization of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs: (A) 3D AFM height profile, (B) TEM image, (C) hydrodynamic diameter profile, (D) FT-IR spectra of BSA, EA, and the EA-Fe@BSA NPs, (E) XPS spectra and fitted curves, (F) absorbance spectrum.

The composition, structural characteristics, and valence of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs were investigated via Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and UV-vis absorption spectroscopy. The bands at 1656 cm-1 (amide I band vibrations) and 1538 cm-1 (amide II band vibrations) observed in the FT-IR spectrum of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs confirmed the presence of BSA. In addition, the slight shift relative to pure BSA of FT-IR spectrum and the fluorescence quenching observed in the fluorescence spectrum further indicated the coordination between Fe and BSA (Figure 1D and S5). In addition, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibited characteristic bands (1185 and 1066 cm-1) similar to those of pure EA (1196 and 1039 cm-1) corresponding to ester C-O stretching, demonstrating the presence of EA. However, the infrared bands displayed a slight shift, indicating the interaction of the EA with the Fe ions. Moreover, the OH stretching bands of pure EA at 3557 and 3474 cm-1 were not observed for the EA-Fe@BSA NPs, demonstrating the successful chelation of the Fe ions by the catechol moieties of EA in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs 42. The valence state of the Fe in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs was further analyzed via XPS. As shown in Figure 1E and S6, peaks corresponding to Fe 2p1/2 (723.5 eV) and Fe 2p3/2 (709.4, 710.8, and 714.8 eV) were observed. The peak at 709.4 eV could be attributed to Fe(II), whereas those at 710.8 and 714.8 eV could be attributed to Fe(III); the peak area ratio of Fe(III)/Fe(II) is about 5.5: 1. These results indicate that the Fe in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs existed in a mixed valence state consisting of both Fe(III) and Fe(II), where Fe(III) was the predominant species 43,44. In addition, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibited strong absorption throughout the visible and NIR region compared with EA and BSA alone (Figure S7), and the characteristic absorption peak at 609 nm may be attributable to the d-d electronic transition of the EA-Fe complex (Figure 1F) 45. These results indicated the potential of the NPs as a photothermal agent for cancer treatment. All of the above results indicated the successful synthesis of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs.

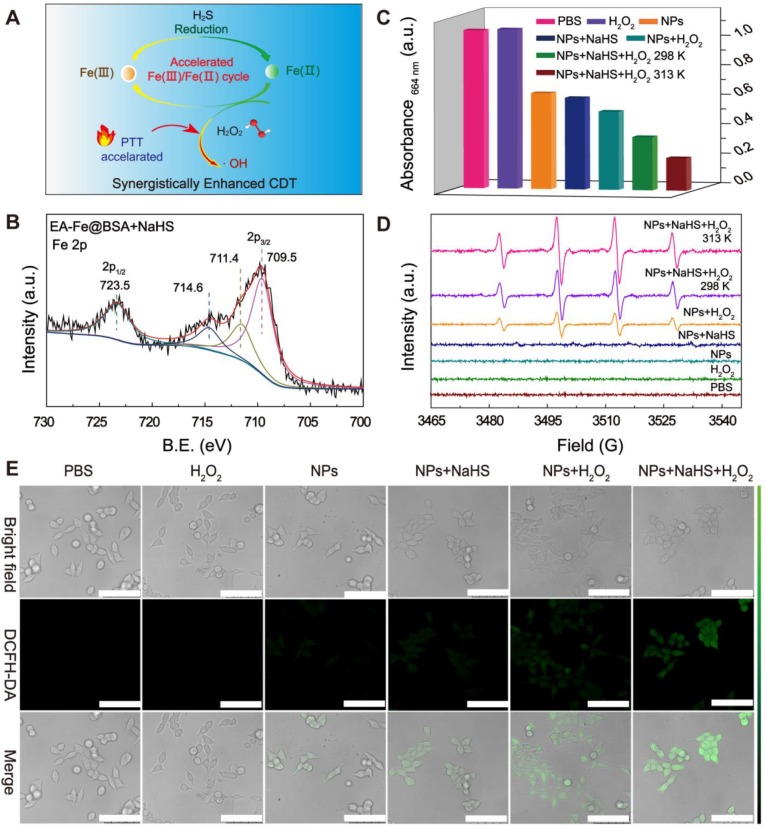

Enhanced CDT Performance In Vitro

The proposed mechanistic process of Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs is as follows. After entering the H2S-rich colon cancer tumor environment, the Fe(III) with low catalytic activity were rapidly reduced by H2S to the more active Fe(II), thereby realizing a rapid Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation system for improved CDT performance. Moreover, the thermal effect led to the generation of more •OH and further improved the CDT performance (Figure 2A). Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) was selected to simulate endogenous H2S to investigate the H2S-enhanced CDT performance in vitro. The valence state of the Fe after the addition of NaHS to the EA-Fe@BSA NPs was analyzed via XPS. As shown in Figure 2B, peaks corresponding to Fe 2p1/2 (723.5 eV) and Fe 2p3/2 (709.5, 711.4, and 714.6 eV) appeared. The peak at 709.5 eV could be attributed to Fe(II), whereas those at 711.4 and 714.6 eV could be ascribed to Fe(III). The peak areas clearly indicated that Fe(II) was the more dominant species, the peak area ratio of Fe(III)/Fe(II) is about 0.5: 1, indicating the reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) by NaHS 46,47. To further confirm the conversion of Fe(III) to Fe(II), 1,10-phenanthroline, which is commonly used as an indicator of Fe(II), was added and the absorbance was detected at 511 nm. As shown in Figure S8, NaHS solution was added to solutions of FeCl3 or EA-Fe@BSA, respectively, followed by the addition of 1,10-phenanthroline. The addition of NaHS led to a significant increase in the absorption peak at 511 nm, indicating the reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) by NaHS, which is similar to that of the other reductive substance, such as GSH (Figure S9) 48. More importantly, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs still exhibit good stability after adding the NaHS (Figure S10). Subsequently, methylene blue (MB) was used to evaluate the generation of •OH. Seven experiments were performed under different conditions (A1: PBS, A2: H2O2, A3: NPs, A4: NPs + NaHS, A5: NPs + H2O2, A6: NPs + NaHS + H2O2 at 298 K, and A7: NPs + NaHS + H2O2 at 313 K), in which these reagents were added to the same concentration of MB solution and reacted for 30 min prior to measuring the absorbance of the solution after centrifugation (Figure S11). The A1 and A2 samples were used as controls. As illustrated in Figure 2C, the MB absorption peak at 664 nm was reduced by approximately 39% in the A3 and A4 samples, which was attributed to adsorption of the MB on the surface of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. The MB absorbance was reduced by approximately 49% in the A5 sample, which was ascribed to the production of •OH by the EA-Fe@BSA NPs in the presence of H2O2. The MB absorbance was reduced by approximately 66% in the A6 sample owing to reduction of the Fe(III) with low catalytic activity in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs to high active Fe(II) by NaHS. It is worth noting that the MB absorbance was reduced by approximately 80% in the A7 sample, which was ascribed to a combination of the reduction of the Fe(III) in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs to Fe(II) by NaHS and the accelerated production of •OH due to the higher temperature. In the conventional Fenton reaction, Fe(II) is oxidized to Fe(III) with the concomitant generation of •OH from H2O2, while the rate of Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation is very slow (0.002-0.01 M-1 s-1), which limits the efficiency of CDT 20. The addition of NaHS and increased temperature solved this problem well, facilitating the Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation and thereby accelerating the CDT.

Figure 2.

Enhanced CDT performance in vitro. (A) Mechanism of H2S accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation to enhance CDT. (B) XPS spectra and fitted curves of EA-Fe@BSA NPs after NaHS addition. (C) MB absorbance values at 664 nm under different conditions, indicating the production of •OH. (D) ESR spectra for •OH detection. (E). Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of HCT116 colon cancer cells stained with DCFH-DA under various conditions (A1: PBS, A2: H2O2, A3: NPs, A4: NPs + NaHS, A5: NPs + H2O2, A6: NPs + NaHS + H2O2 at 298 K, and A7: NPs + NaHS + H2O2 at 313 K; scale bars = 75 μm).

To further explore the CDT performance of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs, the generation of •OH was examined by electron spin resonance (ESR) under seven different sets of conditions. 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), which could capture •OH and exhibit a characteristic four-line 1:2:2:1 spectrum in ESR, was used as a capture agent. As shown in Figure 2D, the characteristic four-line pattern was not observed in the spectra of the A1-A4 samples. In contrast, the four-line pattern was clearly observed in the presence of both EA-Fe@BSA NPs and H2O2 (A5 sample), as the NPs reacted with H2O2 to produce •OH. As expected, a stronger pattern was observed in the presence of NPs, NaHS, and H2O2 (A6 sample), in accordance with the results of the MB discoloration experiment, confirming that NaHS accelerated the transformation of Fe(III)/Fe(II) and therefore the production of •OH. To our delight, upon increasing the temperature (A7 sample), more •OH was detected, further demonstrating the acceleration of the Fenton reaction due to thermal effects and providing the foundation for the subsequent PTT enhancement of CDT.

To evaluate the enhanced CDT performance at the cellular level, 2ʹ,7ʹ-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), which dyes ROS to afford green fluorescence, was used as a staining agent to reveal the production of •OH in the presence of H2O2. As illustrated in Figure 2E, no green fluorescence was observed in the A1 and A2 samples, while only weak fluorescence was observed in the A3 and A4 samples owing to the presence of a small amount of H2O2 in the interstitial cells that reacted with the NPs to generate •OH. This fluorescence was slightly stronger in the A4 sample than in the A3 sample, which was attributed to the NaHS-mediated reduction of the Fe(III)) in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs to Fe(II). In the A5 and A6 samples, the fluorescence was significantly enhanced compared with the samples lacking H2O2, because the addition of exogenous H2O2 increased the Fenton reaction efficacy. Furthermore, the A6 sample exhibited the strongest fluorescence, which was consistent with the results of the MB decolorization experiment and ESR spectra. Owing to a large amount of •OH generated by the NaHS and thermal effects, the cells were almost completely killed in the A7 sample and could not be photographed by confocal laser scanning microscope. All of these results demonstrate that the Fe(III) with low catalytic activity was rapidly reduced by NaHS to the highly active Fe(II) species, resulting in a rapid Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation system for improving the Fenton reaction, combined with thermally enhanced CDT to generate a large amount of •OH, indicating promising performance as an enhanced CDT system for treating colon cancer in vivo.

Photothermal and MRI Performance

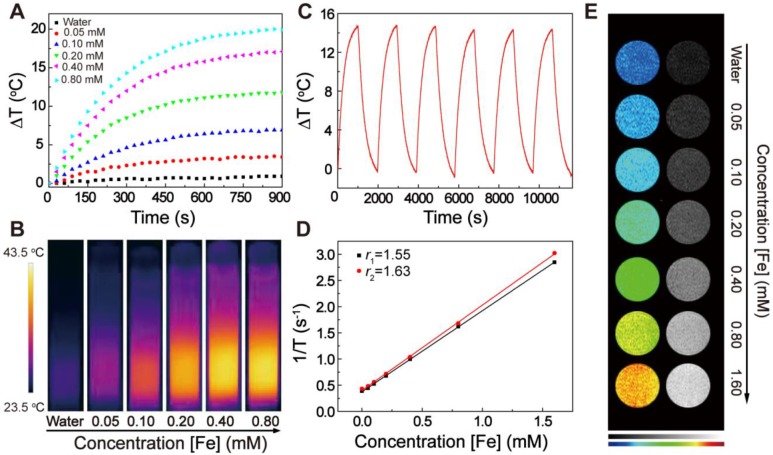

The photothermal properties of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs resulting from their strong NIR absorption were examined. Solutions containing various Fe concentrations of the NPs (0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40, or 0.80 mM) were irradiated with an 808 nm (1 W/cm2) laser for 15 min and the temperature was monitored. As shown in Figure 3A, the solution temperature increased with increasing Fe concentration of the NPs, indicating a concentration-dependent photothermal effect. The corresponding thermal images also revealed that the thermal effect of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs increased with increasing concentration (Figure 3B), clearly demonstrating that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs possess excellent photothermal properties and can rapidly convert NIR light into thermal energy. The temperate change of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs under the irradiation of the laser with different power density further demonstrated that the 1 W/cm2 is the better choose for therapy in our system (Figure S12). Furthermore, the NPs still displayed a good heating effect and morphology after six cycles of heating and cooling, confirming their good photothermal stability (Figure 3C and S13). The photothermal conversion efficiency of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs before and after reaction with NaHS was calculated to be approximately 31.9% and 31.2% (Figure S14), which is similar to previously reported values for Fe-polyphenol-based PTT agents 42. In addition, to examine the influence of H2S, the photothermal properties of the NPs after the addition of NaHS as an exogenous H2S source were also measured under the same conditions. No significant changes in the photothermal curves or NIR thermal images were observed (Figure S15 and S16), demonstrating the good stability of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs as a PTT agent for cancer treatment.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the photothermal and MRI performance of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. (A) Photothermal heating curves of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs at various Fe concentrations (0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40, and 0.80 mM) under irradiation with an 808 nm laser (1 W/cm2). (B) NIR thermal images corresponding to (A). (C) Photothermal cycle measurement for the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. (D) Relaxation rates (r1 and r2) of solutions of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs at 0.5 T. (E) T1-weighted images corresponding to (D).

Fe-polyphenol complexes have also been reported to display good MRI performance 49, indicating the possible additional application of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs as an MRI contrast agent. The longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times were measured for various Fe concentrations of NPs (0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40, 0.80, or 1.60 mM) and the relaxation rate of the NPs was calculated. As shown in Figure 3D, the longitudinal relaxation rate r1 was 1.55 mM-1 s-1 and the transverse relaxation rate r2 was 1.63 mM-1 s-1 50, and consequently r2/r1 = 1.05 < 3, indicating that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs could serve as a T1-weighted contrast agent. T1-weighted MRI measurements confirmed this possibility. The imaging brightness clearly increased with increasing concentration of EA-Fe@BSA NPs, and the color of the T1-weighted images ranged from dark blue (pure water) to orange (Figure 3E). On the basis of these results, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs not only exhibit enhanced CDT effects but also act as a good photothermal agent and a T1-weighted MRI contrast agent for MRI-guided cancer treatment.

Biocompatibility

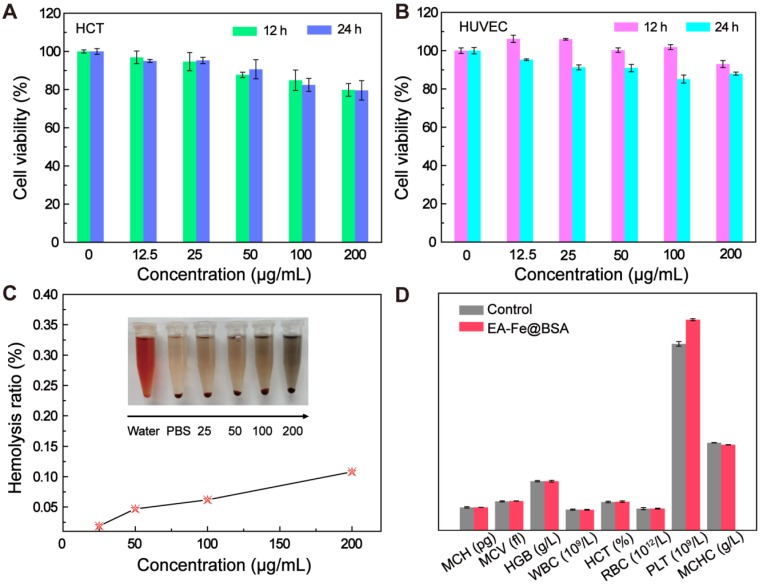

Good biocompatibility is essential for the biological application of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs in vivo. Therefore, the cytotoxicity of the NPs toward HCT116 cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), the hemolysis of red blood cells (RBCs), and routine blood measurements were used to evaluate the biocompatibility prior to in vivo experiments. Various concentrations of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs (0, 12.5, 50.0, 100.0, or 200.0 μg mL-1) were added to colon cancer cells and incubated for 12 or 24 h, after which the viability of the cells was counted using a microplate reader. As shown in Figure 4A, the cell viability decreased with increasing NPs concentration, but the survival rate remained above 80%. The toxicity of the NPs toward HUVECs was studied in a similar manner, and the cell survival rate was also in excess of 80%, indicating the good biocompatibility of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs (Figure 4B). A hemolysis assay was also performed for RBCs incubated with the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. The photograph of the blood supernatant dissolved in water was dark red (positive control), whereas transparent in PBS (negative control). No major hemolysis was observed even when the maximum concentration of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs was dispersed in PBS solution. The hemolysis ratio increased slightly with increasing NP concentration (Figure 4C and S17) but remained less than 5% even at the maximum concentration, further demonstrating the good biocompatibility of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs and establishing a robust foundation for subsequent biological applications. To investigate whether the EA-Fe@BSA NPs had effects on other tissues in vivo, routine blood tests were performed after intravenous injection of the NPs. Three normal nude mice were taken as the control group, and routine blood indices, including the red blood cell count (RBC, 1012/L), white blood cell count (WBC, 109/L), average red blood cell hemoglobin (MCH, pg), mean red blood cell volume (MCV, fl), hemoglobin (HGB, g/L), red blood cell specific volume (HCT, %), platelet count (PLT, 109/L), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC, g/L) were measured. As illustrated in Figure 4D, no significant difference was observed between the control and treated groups for most of the indices. The PLT of the NPs group was higher than that of the normal group, but it was still within the normal range 26. respectively, which are both within the normal range. From the above results, it can be concluded that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs displayed good biocompatibility and low toxicity and were suitable for in vivo experiments.

Figure 4.

Biocompatibility of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. Cell viability tests toward (A) HCT116 cells and (B) HUVECs after incubation with various concentrations of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs for 12 and 24 h. (C) Hemolysis assays for PBS, water, and various concentrations of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. (D) Routine blood tests for normal mice and mice treated with the EA-Fe@BSA NPs (n = 3).

In Vivo MRI

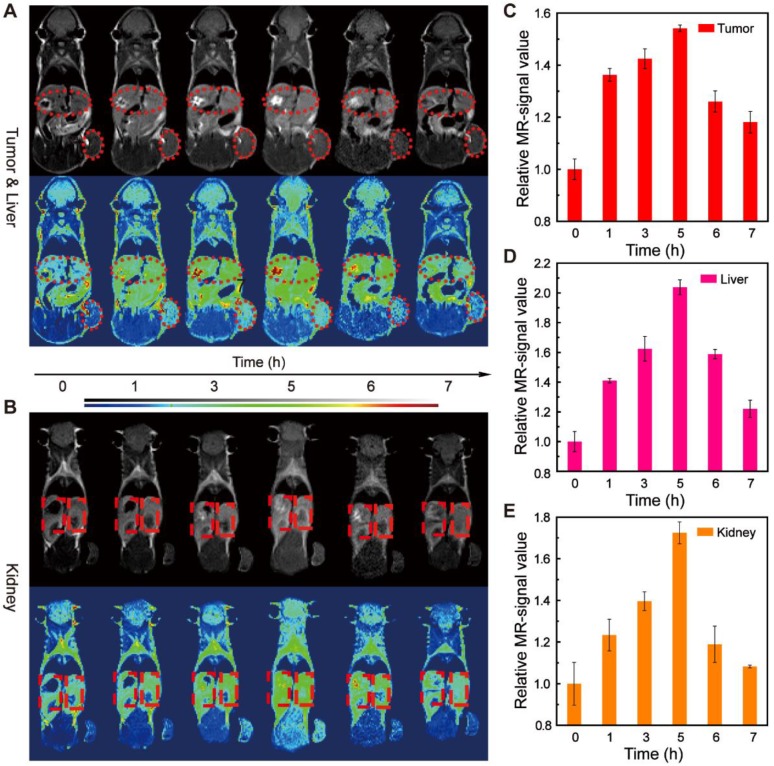

Inspired by the good T1-weighted MRI results in vitro, we further explored the imaging performance of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs in vivo. Background images of colon cancer bearing mice were first acquired, and then the mice were intravenously injected with 3.5 mM Fe concentrations of NPs (20 mg/kg body weight) and images were collected at 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7 h after injection. As shown in Figure 5A, the tumor site became brighter and then darkened over time, and the brightest signal was observed after 5 h. The increased signal was ascribed to the accumulation of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs at the tumor site, where the NPs reached a maximum concentration after 5 h further demonstrate by the biodistribution of EA-Fe@BSA NPs in main organs (Figure S18). Subsequently, the NPs were metabolized and the signal at the tumor site became weaker. Similarly, the signals from the liver and kidneys first became brighter and then gradually darkened over time, and the brightest signal was again observed after 5 h (Figure 5A and 5B). The MRI signal intensity statistics for the tumor site were consistent with the imaging results, indicating that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs had good T1-weighted imaging performance for tumors (Figure 5C). The relative MRI signal intensities for the liver and kidneys exhibited a consistent trend over time (Figure 5D and 5E), revealing that the NPs underwent some degree of retention in the liver and kidneys. These results suggest that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs can be used as an effective T1-weighted MRI contrast agent for tumor-specific diagnosis.

Figure 5.

MRI images of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs in vivo. (A) MRI images of the tumor (indicated with small ellipses) and liver (indicated with large ellipses). (B) MRI images of the kidney (indicated with rectangles). (C-E) Corresponding MRI signal intensities for the images shown in (A, B).

Enhanced CDT Therapy In Vivo

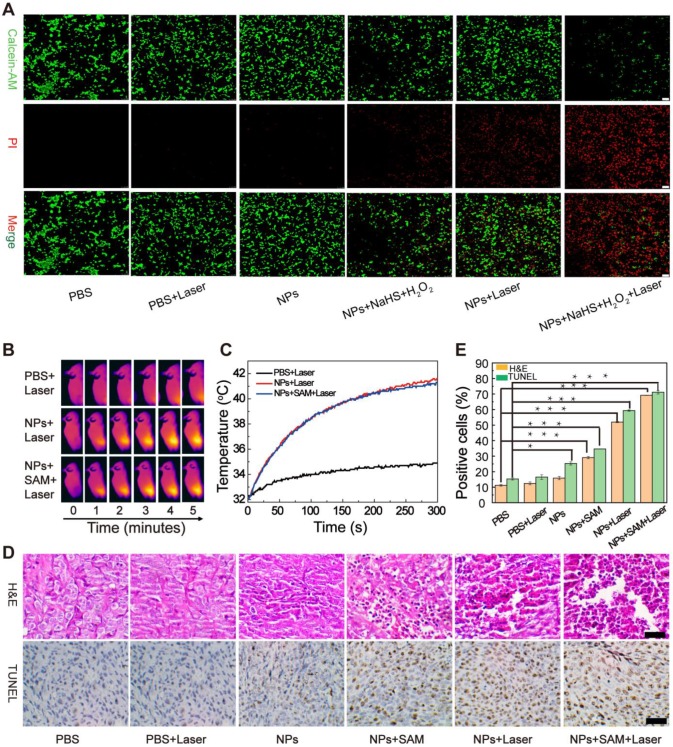

The EA-Fe@BSA NPs displayed good enhanced CDT and PTT performance in vitro, their applicability to tumor treatment still needed to be confirmed in vivo. The enhanced CDT effect was firstly investigated in cells by Calcein-AM/PI staining (Figure 6A). HCT116 cells exhibiting time dependence on NPs uptake (Figure S19) were randomly assigned to six groups: PBS, PBS + Laser, NPs, NPs + NaHS + H2O2, NPs + Laser and NPs + NaHS + H2O2 + Laser. Obviously, the strong green fluorescence was observed in the control group (PBS, PBS + Laser), bits of dead cells were stained by PI in the NPs group. In contrast, significant green fluorescence diminished and red fluorescence intensified in the NPs + NaHS + H2O2, and NPs + Laser group, and most dead cells were appeared in NPs + NaHS + H2O2 + Laser group due to a large amount of •OH generated by the NaHS and thermal effects. The cell viability in each group are further confirmed by the MTT assay, which the NPs + NaHS + H2O2 + Laser group exhibit the lowest cell survival rate (Figure S20). Moreover, ROS-induced apoptosis process was explored by fluorescent probe 5, 5′, 6, 6′-tetrachloro-1, 1′, 3, 3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanine iodide (JC-1). Obvious JC-1 monomer with green fluorescence appeared in the NPs + NaHS + H2O2 + Laser group and significant decrease of the ratio of red/green fluorescence demonstrated the depolarization of mitochondrial membrane and the occurrence of apoptosis (Figure S21 and S22) 51,52.

Figure 6.

Enhanced CDT therapy using the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. (A) The Calcein-AM/PI staining of HCT116 colon cancer cells under different conditions. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Thermal imaging of HCT116 tumor bearing mice injected with PBS, EA-Fe@BSA NPs, or EA-Fe@BSA+SAM NPs under laser irradiation. (C) Corresponding temperature increase of the tumor site in (B). (D) H&E (top) and TUNEL (bottom) staining of tumor sections from various groups of mice (B1: PBS, B2: PBS + laser, B3: NPs, B4: NPs + SAM, B5: NPs + laser, and B6: NPs + SAM + laser). Scale bar = 50 μm. (E) Proportion of necrosis area and TUNEL-positive cells for the different groups (n = 5, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05).

Inspired by this, the enhanced CDT effect were further validated in vivo. HCT116 tumor-bearing mice were divided into three groups (PBS, NPs, and NPs + S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)) for intravenous injection with PBS or the NPs. The PBS group was used as the control group, and the NPs and NPs + SAM groups were used as the experimental groups. For the NPs + SAM group, the H2S promoter SAM which was used to promote the mice to generated more H2S by the body was intraperitoneally injected into the mice 24 h prior to the injection of the NPs, which was further to demonstrate that the H2S can accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion to enhance the treatment effect. As the in vivo MRI results had revealed the highest concentration of NPs in the tumor after 5 h, the three groups were subjected to 808 nm laser irradiation 5 h after injection, and photothermal images were recorded at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 min during irradiation (Figure 6B). For the animals in the control group, the temperature of the tumor site increased by approximately 2 °C, whereas that for the animals in the experimental groups increased by approximately 10 °C (Figure 6C), demonstrating that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs afforded a measurable photothermal heating effect in mice. It is worth noting that no difference was observed between the two experimental groups and the temperature of the tumor site for both groups increased to approximately 41 °C, which is a relatively safe temperature that could reduce the adverse effects of heat treatment on normal tissues. More importantly, H2S did not interfere with the PTT effect of the NPs, which is beneficial for synergistically enhancing CDT performance using PTT. Next, the influence of enhanced CDT on the tumors was evaluated at the histological level. Tissue sections of the tumor sites were excised from various groups of mice (B1: PBS (control), B2: PBS + laser (laser control), B3: NPs (for CDT), B4: NPs + SAM (for H2S-enhanced CDT), B5: NPs + laser (for PTT-enhanced CDT), and B6: NPs + SAM + laser (for synergistically enhanced CDT)) and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining (Figure 6D). Almost no cellular damage was observed in the B1 and B2 groups, while a weak CDT effect was observed for the B3 group. In contrast, owing to the high concentration of H2S induced by the S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) and valence conversion, the B4 group displayed an enhanced CDT effect in the colon tumor cells. The morphology of the tumor cells was destroyed and the nucleus was no longer in the cells. In the B5 group, obvious cell necrosis was observed owing to the PTT-enhanced CDT. A more prominent killing effect was observed in the B6 group, demonstrating outstanding enhanced CDT efficiency upon H2S and PTT acceleration. Quantitative analysis of the TUNEL-stained sections revealed that the proportions of TUNEL-positive cells for the B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, and B6 groups were 15.31%, 16.56%, 25.27%, 34.65%, 59.38%, and 71.18%, respectively (Figure 6E). Compared with the B1 and B2 groups, the intrinsic CDT efficiency in the B3 group was very low. Excitingly, a higher cell mortality rate occurred upon increasing the H2S concentration and in combination with PTT-promoted CDT, further validating the efficiency of the enhanced CDT approach. The above analysis revealed that the synergistically enhanced CDT group displayed the best treatment effects for colon tumors, indicating great potential for colon cancer therapy in vivo.

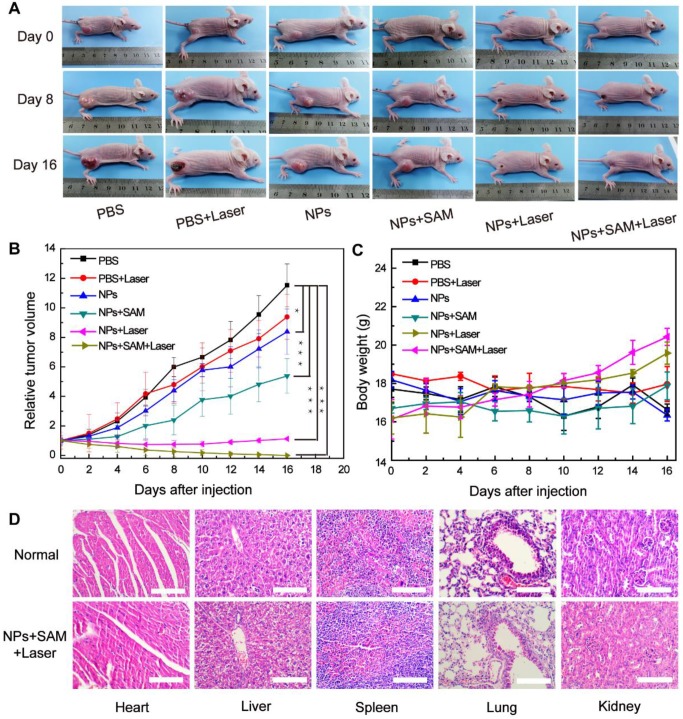

The enhanced CDT effects of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs for colon tumor ablation were further explored by examining photographs of the tumor-bearing mice, tumor volume, and body weight over 16 days. As shown in Figure 7A, the tumor growth rate in the B3 group was lower than that in the B1 and B2 groups, which was attributed to the weak CDT effect in the B3 group. The tumor growth rate in the B4 group was also lower than that in the B3 group, owing to the administration of the H2S accelerant; more H2S was produced in the tumor site of the mice, leading to greater reduction of the Fe(III) in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs to Fe(II) and promoting the CDT efficiency. Unfortunately, tumor growth was still not completely inhibited under these conditions. In the B5 group, the tumors were inhibited in the first week, but a certain degree of recurrence occurred after 10 d in the vicinity of the original tumor. Remarkably, in the B6 group, the tumors were completely cured after 16 d. These results demonstrate that the synergistically enhanced CDT can effectively treat colon cancer tumors in mice. This finding was also supported by the relative tumor volume statistics for the various groups of mice. As shown in Figure 7B, the tumor growth rate increased rapidly in the B1, B2, and B3 groups, while the tumor volume was inhibited to a certain extent in the B4 group owing to the H2S-enhanced CDT effect of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. Compared with the B5 group, the tumors in the B6 group were more greatly suppressed and completely cured after 16 d, demonstrating the superior tumor inhibition effect of the synergistically enhanced CDT for colon cancer treatment. Even though the H2S-enhanced CDT still cannot inhibit the tumor alone, the synergy of H2S-enhanced CDT and photothermal-enhanced CDT can remove the tumor completely. Thus, the contribution of H2S-enhanced CDT can further lower the requirement of laser density or irradiation time for photothermal therapy to reducing the damage to normal tissues, which can be used to guide the design of treatment plans in the future. The body weight changes for each group of mice were tracked every 2 d. As shown in Figure 7C, the body weight remained stable for all of the groups, indicating that the EA-Fe@BSA NPs and the overall treatment method induced no toxic side effects in mice. Combined with the in vivo treatment results, the results demonstrate that enhanced CDT and PTT alone failed to inhibit the tumors, whereas the synergistically enhanced CDT completely cured colon cancer in mice. To visually compare the therapeutic effects for the different groups, the tumors were excised after 16 d of treatment. As shown in Figure S23, the tumor size clearly decreased with the gradually enhanced CDT effects and the tumors had completely disappeared for the B6 group. In addition, there was no significant difference in the H&E staining sections of the main organs between the normal and cured mice (Figure 7D), which further proved the biosafety of the NPs in vivo and good treatment effect. All of the above data demonstrate that the CDT performance of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs was synergistically enhanced by endogenous H2S and PTT, and the combination of enhanced CDT and PTT based on a single agent is expected to be a more efficient therapeutic strategy for colon cancer.

Figure 7.

Treatment results for mice in the various groups (B1: PBS, B2: PBS + laser, B3: NPs, B4: NPs + SAM, B5: NPs + laser, and B6: NPs + SAM + laser). (A) Photographs of tumor-bearing mice on days 0, 8, and 16 of during follow-up treatment for 16 d. (B) Relative tumor volume (n = 5, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05). (C) Body weight. (D) H&E staining of the main organs of normal and cured mice. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Experimental

Materials

Iron(III) chloride hexahydrate was supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). BSA was purchased from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA). Ellagic acid (96%) was obtained from Aladdin Industrial Corporation (Shanghai, China). All reagents were used without further purification.

Synthesis of EA-Fe@BSA NPs

BSA (66.6 mg) was dissolved in deionized water (9 mL) under magnetic stirring. Then, 108 μL of aqueous FeCl3 solution (0.1 g mL-1) was added. After stirring at room temperature for 30 min, an ethanolic solution of EA (1002 μL, 10 mg mL-1) was added dropwise. After stirring overnight, the solution turned dark blue. The EA-Fe@BSA NPs were collected by ultrafiltration centrifugation and washed several times with water.

Characterization

AFM and TEM (JEM-2010F, JEOL) were used to measure the sizes and morphologies of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. The hydrated particle size of the NPs was determined using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS. The surface ion valency and composition of the NPs were measured by XPS (Axis 165, Kratos). Fluorescence spectra were recorded using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Cary Eclipse, Agilent). NIR absorption spectra were measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (DU 730, Beckman Coulter). FT-IR spectra were obtained using a FT-IR spectrophotometer (Nicolet Avatar 370, Thermo).

Biocompatibility

MTT assays were used to evaluate the toxicity of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs toward HUVECs and HCT116 colon cancer cells. First, 100 μL aliquots of cells (105 mL-1) were plated on a 96-well plate. After incubation for 12 h, a series of RPMI 1640 medium containing the EA-Fe@BSA NPs (10, 25, 50, 100, 200 μg mL-1) was added to the well plate. After incubation for 12 h or 24 h, the supernatant in all wells was aspirated, MTT solution was then added to each well and allowed to stand in the incubator for another 4 h. The supernatant was then discarded, rinsed twice with PBS, followed by adding dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Finally, the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (Varioskan Flash, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RBCs were collected from normal BALB/c nude mice (Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences) for hemolysis experiments to assess the biocompatibility of the NPs. First, the RBCs (0.4 mL) were added to 1 mL of water as a positive control. A second sample of RBCs was added to PBS as a negative control. Samples of RBCs were also added to PBS containing various concentrations of the NPs (25, 50, 100, or 200 μg mL-1). After allowing the samples to stand for 1 h, they were centrifuged at a low speed and the absorbance of the supernatant at 576 nm was measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer. The percent hemolysis was then calculated using the formula:

| (At-Anc)/(Apc-Anc)×100%, |

where Apc, At, and Anc represent the absorbances of the positive control, NP sample, and negative control at 576 nm, respectively.

Routine blood experiments were performed to further assess the toxicity of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs to mice. Blood samples were collected from three normal BALB/c nude mice and three treated mice for routine blood analysis.

In Vitro and In Vivo MRI Performance

The in vitro transverse relaxation rate, longitudinal relaxation rate, and MRI were measured on a 0.5 T MRI instrument, and various Fe concentrations of EA-Fe@BSA NPs (0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40, 0.80, and 1.60 mM) were added to centrifuge tubes for MRI scanning. The in vitro T1-weighted MRI parameters included an echo time (TE) of 0.04 ms, a spectrometer frequency offset of the first channel (SFO1) of 18.538 MHz, a repetition time (TR) of 200 ms, a slice width of 4 mm.

In vivo T1-weighted MRI was conducted on a 0.5 T MRI instrument (MiniMR-60, Niumag), BALB/c nude mice inoculated with HCT116 cells (Shanghai Experimental Animal Center) were used in the experiments. Coronal scanning was performed before and after the injection of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs (1, 3, 5, 6, and 7 h). The dosage of EA-Fe@BSA NPs was 100 μL (3.5 mM). The in vivo T1-weighted MRI parameters included a field of view of 80 × 80 mm, a TR of 340 ms, a TE of 18.125 ms, a slice thickness of 3 mm.

In Vitro and In Vivo Photothermal Performance

To evaluate the photothermal performance in vitro, a thermal imaging camera (A300, FLIR) was used to measure the temperature change for pure water and various concentrations of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs. To evaluate the photothermal stability of the NPs, the sample was subjected to laser irradiation (808 nm laser, 1 W cm-2) for 15 min followed by a cooling down period of 15 min, and this cycle was repeated six times. The photothermal conversion efficiency was calculated according to our previous report 53.

To evaluate the photothermal performance in vivo, 100 μL (3.5 mM) of the NPs or PBS were separately injected into HCT116 tumor bearing mice through the tail vein. After 5 h, the tumor sites were irradiated with an 808 nm laser (1 W cm-2) for 5 min and the temperature change was recorded by thermography.

Enhanced CDT Performance In Vitro

The CDT performance was assessed using the levels of •OH. The MB colorimetric method was used to monitor the generation of •OH under various conditions, and H2S was simulated using NaHS. The experiment involved seven samples (A1: PBS, A2: H2O2, A3: NPs, A4: NPs + NaHS, A5: NPs + H2O2, A6: NPs + NaHS + H2O2 at 298 K, and A7: NPs + NaHS + H2O2 at 313 K). The concentrations of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs, NaHS, and H2O2 were 0.2 mM, 3 mM, and 100 μM, respectively. A1-A6 samples were stored at 298 K for 30 min and A7 samples were stored at 313 K for 30 min, then subjected to ultrafiltration centrifugation; the NPs were left in the ultrafiltration tube following centrifugation and absorbance of the filtrate was measured.

The •OH produced in the different samples was further measured via X-band ESR spectroscopy using DMPO as a capture agent for •OH. DMPO solution (100 μL, 100 mM) was added to each sample and the resulting mixture was transferred to a quartz capillary for measurement of the ESR spectra (E500-10/12, Bruker).

To evaluate the CDT performance in cells, DCFH-DA was used as a fluorescence indicator and the intracellular ROS production was measured via confocal laser scanning imaging. First, HCT116 cells seeded in specific culture dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 12 h under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Next, they were incubated with the various samples (A1-A7; 100 μg/mL NPs, 3 mM NaHS, and 100 μM H2O2) for 5 h, washed twice with PBS, and then dyed with DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 30 min. After washing with PBS, the fluorescence was detected via confocal laser scanning microscopy (TCS SP5, Leica, Germany).

For Calcein-AM/PI staining, HCT116 cells were seeded in glass based dishes and incubated at 37 °C for 12 h under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Next, they were incubated with the various samples (PBS, PBS + Laser, NPs, NPs + NaHS + H2O2, NPs + Laser, NPs + NaHS + H2O2 + Laser; 100 μg/mL NPs, 3 mM NaHS, and 100 μM H2O2) for 5 h. For groups requiring laser irradiation, the cells were irradiated by 808 nm laser for 5 min (1 W/cm2), and then dyed with calcein-AM and PI solution for 25 min. After washing with PBS, the fluorescence was detected via confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Enhanced CDT Performance In Vivo

HCT116 tumor bearing mice (enrich in H2S) were divided into six groups (B1: PBS, B2: PBS + laser, B3: NPs, B4: NPs + SAM, B5: NPs + laser, and B6: NPs + SAM + laser) with six mice per group. SAM is a common inducer that can improve CBS enzymatic activity, leading to increased H2S concentrations. First, the animals in the B4 and B6 groups were injected with SAM, and 24 h later the animals in the B1 and B2 groups were injected with 100 μL PBS while those in the B3, B4, B5, and B6 groups were injected with 100 μL (3.5 mM) Fe concentrations of NPs. After a further 5 h, the animals in the B2, B5, and B6 groups were subjected to irradiation with an 808 nm laser (1 W cm-2) for 5 min. Subsequently, the tumors were excised from one mouse in each group for H&E and TUNEL staining. Finally, the body weight and tumor volume (tumor width2 × tumor length/2) of the remaining mice in each group were monitored for 16d.

Conclusion

In summary, ultra-small EA-Fe@BSA NPs with good biocompatibility were synthesized via the simple assembly of a natural polyphenol, Fe(III) and albumin for enhanced CDT. In vitro enhanced CDT results revealed that a significant amount of •OH was detected upon the addition of NaHS and increasing the temperature. The Fe(III) with low catalytic activity was rapidly reduced to Fe(II) by the abundant H2S, providing a rapid Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion system to improve the regeneration of Fe(II). Importantly, the EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibited strong NIR absorption and excellent photothermal conversion efficiency both in vitro and in vivo, which is beneficial for tumor inhibition by PTT-enhanced CDT. Moreover, the low r2:r1 ratio (1.05) and good MRI performance of the as-obtained EA-Fe@BSA NPs indicated great promise as a T1-weighted MRI diagnostic reagent. Tumor ablation experiment results demonstrated that endogenous H2S and PTT could synergistically enhance the CDT efficiency, significantly suppressing and curing tumors in mice. After injection of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs into mice and their transportation to the unique microenvironment of colon cancer tumors, the NPs not only underwent Fe(III) reduction to Fe(II) by endogenous H2S, thereby expediting the Fe(III)/Fe(II) transformation for CDT enhancement based on the Fenton reaction, but also mediated PTT effects under NIR irradiation to generate more •OH, thereby realizing synergistically enhanced CDT. This synergistically enhanced CDT strategy, which exploits endogenous reducing substances in tumor cells, provides a promising paradigm for colon cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 91959105 and 21671135), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (17QA1402600), Shanghai Talent Development Fund (2018082), Shanghai Sailing Program (19YF1436200), Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Green Energy Chemical Engineering (18DZ2254200), and International Joint Laboratory on Resource Chemistry (IJLRC).

Abbreviations

- CDT

chemodynamic therapy

- H2S

endogenous hydrogen sulfide

- EA-Fe@BSA

ellagic acid-Fe-bovine serum albumin

- NIR

near-infrared

- •OH

hydroxyl radicals

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CBS

cystathionine-β-synthase

- PTT

photothermal therapy

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- FT-IR

fourier-transform infrared

- XPS

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

- NaHS

Sodium hydrosulfide

- ESR

electron spin resonance

- DMPO

5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide

- DCFH-DA

2ʹ,7ʹ-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- SAM

S-adenosyl-l-methionine

References

- 1.Conde J, Oliva N, Zhang Y, Artzi N. Local triple-combination therapy results in tumour regression and prevents recurrence in a colon cancer model. Nat mater. 2016;15:1128–38. doi: 10.1038/nmat4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao B, Viennois E, Chen Q, Wang L, Han MK, Zhang Y. et al. Silencing of intestinal glycoprotein CD98 by orally targeted nanoparticles enhances chemosensitization of colon cancer. ACS Nano. 2018;12:5253–65. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao X, Ding L, Xie ZZ, Yang Y, Whiteman M, Moore PK. et al. A review of hydrogen sulfide synthesis, metabolism, and measurement: is modulation of hydrogen sulfide a novel therapeutic for cancer? Antioxid Redox Sign. 2018;31:1–38. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Zhu C, Yang Z, Chen J, He Y, Jiao Y. et al. A ratiometric fluorescent probe for rapid detection of hydrogen sulfide in mitochondria. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:1688–91. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szabó C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2007;6:917–35. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo C, Coletta C, Chao C, Módis K, Szczesny B, Papapetropoulos A. et al. Tumor-derived hydrogen sulfide, produced by cystathionine-β-synthase, stimulates bioenergetics, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2013;110:12474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306241110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu YC, Wang XJ, Yu L, Chan FKL, Cheng ASL, Yu J. et al. Hydrogen sulfide lowers proliferation and induces protective autophagy in colon epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An L, Wang X, Rui X, Lin J, Yang H, Tian Q. et al. The in situ sulfidation of Cu2O by endogenous H2S for colon cancer theranostics. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:15782–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201810082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Zhang H, Zhang M, Zhao P, Song R, Gong T. et al. Amorphous Fe-based nanoagents for self-enhanced chemodynamic therapy by re-establishing tumor acidosis. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30:1908365. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Wang D, Zhang S, Cheng Y, Yang F, Xing Y. et al. Biodegradable biomimic copper/manganese silicate nanospheres for chemodynamic/ photodynamic synergistic therapy with simultaneous glutathione depletion and hypoxia relief. ACS Nano. 2019;13:4267–77. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma Pa, Xiao H, Yu C, Liu J, Cheng Z, Song H. et al. Enhanced cisplatin chemotherapy by iron oxide nanocarrier-mediated generation of highly toxic reactive oxygen species. Nano Lett. 2017;17:928–37. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Yin W, Ke W, Chen W, He C, Ge Z. Multifunctional polymeric micelles with amplified fenton reaction for tumor ablation. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:1990–8. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C, Bu W, Ni D, Zhang S, Li Q, Yao Z. et al. Synthesis of iron nanometallic glasses and their application in cancer therapy by a localized fenton reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:2101–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang A, Pan S, Zhang Y, Chang J, Cheng J, Huang Z. et al. Carbon-gold hybrid nanoprobes for real-time imaging, photothermal/photodynamic and nanozyme oxidative therapy. Theranostics. 2019;9:3443–58. doi: 10.7150/thno.33266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Lin J, Wang T, Chen X, Huang P. Recent advances in photoacoustic imaging for deep-tissue biomedical applications. Theranostics. 2016;6:2394–413. doi: 10.7150/thno.16715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon B, Han E, Yang W, Cho W, Yoo W, Hwang J. et al. Nano-fenton reactors as a new class of oxidative stress amplifying anticancer therapeutic agents. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:5887–97. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin LS, Song J, Song L, Ke K, Liu Y, Zhou Z. et al. Simultaneous fenton-like ion delivery and glutathione depletion by MnO2-based nanoagent to enhance chemodynamic therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:4902–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Liu Y, Wang J, Wei T, Dai Z. Mild hyperthermia-enhanced enzyme-mediated tumor cell chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:23065–71. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b08257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papatheodorou P, Carette JE, Bell GW, Schwan C, Guttenberg G, Brummelkamp TR. et al. Lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor (LSR) is the host receptor for the binary toxin clostridium difficile transferase (CDT) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16422–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109772108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwan C, Kruppke AS, Nölke T, Schumacher L, Koch-Nolte F, Kudryashev M. et al. Clostridium difficile toxin CDT hijacks microtubule organization and reroutes vesicle traffic to increase pathogen adherence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2313–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311589111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Z, Zhang H, Liu Y, Ni D, Zhang H, Zhang J. et al. Antiferromagnetic pyrite as the tumor microenvironment-mediated nanoplatform for self-enhanced tumor imaging and therapy. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1701683. doi: 10.1002/adma.201701683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Wan SS, Li CX, Xu L, Cheng H, Zhang XZ. An adenosine triphosphate-responsive autocatalytic fenton nanoparticle for tumor ablation with self-supplied H2O2 and acceleration of Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion. Nano Lett. 2018;18:7609–18. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Wang X, Liu Y, Liu H, Gao F, Lan C. et al. pH-responsive catalytic mesocrystals for chemodynamic therapy via ultrasound-assisted Fenton reaction. Chem Eng J. 2019;369:394–402. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Q, Luo Y, Du W, Liu Z, Zhang S, Yang J. et al. Clearable theranostic platform with a pH-independent chemodynamic therapy enhancement strategy for synergetic photothermal tumor therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:18133–44. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b02905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin LS, Huang T, Song J, Ou XY, Wang Z, Deng H. et al. Synthesis of copper peroxide nanodots for H2O2 self-supplying chemodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:9937–45. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu P, Wang Y, An L, Tian Q, Lin J, Yang S. Ultrasmall WO3-x@γ-poly-l-glutamic acid nanoparticles as a photoacoustic imaging and effective photothermal-enhanced chemodynamic therapy agent for cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:38833–44. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b15678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Z, Wang W, Li C, Zhang Y, Yu T, Wu R. et al. Reactive oxygen species-activatable liposomes regulating hypoxic tumor microenvironment for synergistic photo/chemodynamic therapies. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;0:1905013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Z, Feng L, Chao Y, Hao Y, Chen M, Gong F. et al. Amplification of tumor oxidative stresses with liposomal Fenton catalyst and glutathione inhibitor for enhanced cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nano Lett. 2019;19:805–15. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong Z, Yang Z, Hao Y, Feng L. Fabrication of H2O2-driven nanoreactors for innovative cancer treatments. Nanoscale. 2019;11:16164–86. doi: 10.1039/c9nr04418c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang Z, Liu Y, He M, Bu W. Chemodynamic therapy: tumour microenvironment-mediated fenton and fenton-like reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58:946–56. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou X, Huang X, Ai Z, Zhao J, Zhang L. Ascorbic acid/Fe@Fe2O3: A highly efficient combined fenton reagent to remove organic contaminants. J Hazard Mater. 2016;310:170–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou X, Huang X, Ai Z, Zhao J, Zhang L. Ascorbic acid induced atrazine degradation. J Hazard Mater. 2017;327:71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y, Jiang Y, Xiao Z, Shen Y, Huang L, Xu X. et al. Three birds with one stone: A ferric pyrophosphate based nanoagent for synergetic NIR-triggered photo/chemodynamic therapy with glutathione depletion. Chem Eng J. 2020;380:122369. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Chong Y, Liu X, Fu H, Yu C, Huang J. et al. Multifunctional nanotheranostic gold nanocages for photoacoustic imaging guided radio/ photodynamic/photothermal synergistic therapy. Acta Biomater. 2019;84:328–38. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Zhang C, Gong S, Li X, Yu M, Qian C. et al. A nanoscale photothermal agent based on a metal-organic coordination polymer as a drug-loading framework for effective combination therapy. Acta Biomater. 2019;94:435–46. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao D, Zhang B, Liu Y, Hu D, Sheng Z, Zhang X. et al. Molecular engineering of near-infrared light-responsive BODIPY-based nanoparticles with enhanced photothermal and photoacoustic efficiencies for cancer theranostics. Theranostics. 2019;9:5315–31. doi: 10.7150/thno.34418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Huang P, Lin J. Plasmonic gold nanovesicles for biomedical applications. Small. 2019;3:1800394. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu F, Lin L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Sheng S, Xu C. et al. A tumor- microenvironment-activated nanozyme-mediated theranostic nanoreactor for imaging-guided combined tumor therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;0:1902885. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Zhao J, Chen Z, Zhang F, Wang Q, Guo W. et al. Construct of MoSe2/Bi2Se3 nanoheterostructure: multimodal CT/PT imaging-guided PTT/PDT/chemotherapy for cancer treating. Biomaterials. 2019;217:119282. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie Z, Liang S, Cai X, Ding B, Huang S, Hou Z. et al. O2-Cu/ZIF-8@Ce6/ZIF-8@F127 composite as a tumor microenvironment-responsive nanoplatform with enhanced photo-/chemodynamic antitumor efficacy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:31671–80. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b10685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou W, Guan H, Sun K, Xing Y, Zhang J. FeOOH/polypyrrole nanocomposites with an islands-in-sea structure toward combined photothermal/chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2019;2:2708–14. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao G, Wu H, Feng R, Wang D, Xu P, Jiang P. et al. Novel metal polyphenol framework for MR imaging-guided photothermal therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:3295–304. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b16222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding B, Shao S, Jiang F, Dang P, Sun C, Huang S. et al. MnO2-disguised upconversion hybrid nanocomposite: An ideal architecture for tumor microenvironment-triggered UCL/MR bioimaging and enhanced chemodynamic therapy. Chem Mater. 2019;31:2651–60. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu Y, Lv T, Ma Y, Xu J, Zhang Y, Hou Y. et al. Nanoscale coordination polymers for synergistic NO and chemodynamic therapy of liver cancer. Nano Lett. 2019;19:2731–8. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng J, Cheng M, Wang Y, Wen L, Chen L, Li Z. et al. pH-responsive Fe(III)-gallic acid nanoparticles for in vivo photoacoustic-imaging-guided photothermal therapy. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2016;5:772–80. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong S, Xu J, Jia T, Xu M, Zhong C, Yang G. et al. Upconversion-mediated ZnFe2O4 nanoplatform for NIR-enhanced chemodynamic and photodynamic therapy. Chem sci. 2019;10:4259–71. doi: 10.1039/c9sc00387h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao P, Tang Z, Chen X, He Z, He X, Zhang M. et al. Ferrous-cysteine-phosphotungstate nanoagent with neutral pH fenton reaction activity for enhanced cancer chemodynamic therapy. Mater Horiz. 2019;6:369–74. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nie X, Xia L, Wang HL, Chen G, Wu B, Zeng TY. et al. Photothermal therapy nanomaterials boosting transformation of Fe(III) into Fe(II) in tumor cells for highly improving chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:31735–42. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b11291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An L, Yan C, Mu X, Tao C, Tian Q, Lin J. et al. Paclitaxel-induced ultrasmall gallic acid-Fe@BSA self-assembly with enhanced MRI performance and tumor accumulation for cancer theranostics. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:28483–93. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b10625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dai Y, Xiao H, Liu J, Yuan Q, Ma Pa, Yang D. et al. In vivo multimodality imaging and cancer therapy by near-infrared light-triggered trans-platinum pro-drug-conjugated upconverison nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18920–9. doi: 10.1021/ja410028q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu P, Wu T, Fan W, Chen L, Liu Y, Ni D. et al. Near infrared-assisted Fenton reaction for tumor-specific and mitochondrial DNA-targeted photochemotherapy. Biomaterials. 2017;141:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang T, Zhang H, Liu H, Yuan Q, Ren F, Han Y. et al. Boosting H2O2-guided chemodynamic therapy of cancer by enhancing reaction kinetics through versatile biomimetic Fenton nanocatalysts and the second near-infrared light irradiation. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;3:1906128. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian Q, Jiang F, Zou R, Liu Q, Chen Z, Zhu M. et al. Hydrophilic Cu9S5 nanocrystals: A photothermal agent with a 25.7% heat conversion efficiency for photothermal ablation of cancer cells in vivo. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9761–71. doi: 10.1021/nn203293t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.