Abstract

Background

For a long time pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) has been the most common form of conservative (non‐surgical) treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Weighted vaginal cones can be used to help women to train their pelvic floor muscles. Cones are inserted into the vagina and the pelvic floor is contracted to prevent them from slipping out.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to determine the effectiveness of vaginal cones in the management of female urinary stress incontinence (SUI).

We wished to test the following comparisons in the management of stress incontinence: 1. vaginal cones versus no treatment; 2. vaginal cones versus other conservative therapies, such as PFMT and electrostimulation; 3. combining vaginal cones and another conservative therapy versus another conservative therapy alone or cones alone; 4. vaginal cones versus non‐conservative methods, for example surgery or injectables.

Secondary issues which were considered included whether: 1. it takes less time to teach women to use cones than it does to teach the pelvic floor exercise; 2. self‐taught use is effective; 3. the change in weight of the heaviest cone that can be retained is related to the level of improvement; 4. subgroups of women for whom cone use may be particularly effective can be identified.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register (searched 19 September 2012), MEDLINE (January 1966 to March 2013), EMBASE (January 1988 to March 2013) and reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing weighted vaginal cones with alternative treatments or no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed studies for inclusion and trial quality. Data were extracted by one reviewer and cross‐checked by the other. Study authors were contacted for extra information.

Main results

We included 23 trials involving 1806 women, of whom 717 received cones. All of the trials were small, and in many the quality was hard to judge. Outcome measures differed between trials, making the results difficult to combine. Some trials reported high drop‐out rates with both cone and comparison treatments. Seven trials were published only as abstracts.

Cones were better than no active treatment (rate ratio (RR) for failure to cure incontinence 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 to 0.94). There was little evidence of difference for a subjective cure between cones and PFMT (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.13), or between cones and electrostimulation (RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.87), but the confidence intervals were wide. There was not enough evidence to show that cones plus PFMT was different to either cones alone or PFMT alone. Only seven trials used a quality of life measures and no study looked at economic outcomes.

Seven of the trials recruited women with symptoms of incontinence, while the others required women with urodynamic stress incontinence, apart from one where the inclusion criteria were uncertain.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides some evidence that weighted vaginal cones are better than no active treatment in women with SUI and may be of similar effectiveness to PFMT and electrostimulation. This conclusion must remain tentative until larger, high‐quality trials, that use comparable and relevant outcomes, are completed. Cones could be offered as one treatment option, if women find them acceptable.

Plain language summary

Vaginal weights for training the pelvic floor muscles to treat urinary incontinence in women

Leaking urine when coughing, sneezing, or exercising (stress urinary incontinence) is a common problem for women. This is especially so after giving birth, when about one woman in three will leak urine. Training of the pelvic floor muscles is the most common form of treatment for this problem. One way that women can train these muscles is by inserting cone‐shaped weights into the vagina, and then contracting the pelvic floor muscles to stop the weights from slipping out again.

Twenty‐three small trials, involving 1806 women, were found. The results of these trials consistently showed that the use of vaginal weights is better than having no treatment. When vaginal weights were compared to other treatments, such as pelvic floor muscle training without the weights, and electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor, no clear differences between the treatments were evident. This may have been because the numbers of participants in the trials were small, and larger numbers may be required for any differences in the effectiveness of treatments to become clear.

Some women find vaginal weights unpleasant or difficult to use, so this treatment may not be useful for all women.

Many women with stress urinary incontinence will not be cured by these treatments, and so it is important for trials to assess quality of life during and after treatment, but few of these trials did. Most of the trials were of fairly short duration, so it is difficult to say what happens to women with stress urinary incontinence in the longer term.

Background

Description of the condition

The classic symptom of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is an involuntary loss of urine during physical exertion (e.g. coughing, laughing, sneezing, and exercise) (Abrams 1989). There are a variety of predisposing factors for SUI, which include pregnancy and vaginal delivery (Wilson 1996), obesity (Bump 1992a; Wilson 1996), and cigarette smoking (Bump 1992b). The strong causal link between childbearing and SUI means that it is a common problem in adult women with reported prevalences of 17% to 45% (Jolleys 1988).

The impact of incontinence on quality of life can be considerable for sufferers, with many reporting effects on their social, domestic, physical, occupational and leisure activities (Wyman 1990). Apart from the personal and social cost to sufferers, the direct and indirect healthcare costs are substantial (Hu 1990).

Normally the bladder and urethra are supported within the pelvic cavity by ligamentous and fascial attachments, and the levator ani (a pelvic floor muscle) (Morley 1995). Descent of the bladder and urethra have been observed in stress incontinent women (Hanzal 1993), and it is believed that this hypermobility results from a lack of ligamentous and fascial support. In addition, denervation injuries of the levator ani during vaginal delivery may contribute to changes in position of the bladder and urethra, and a reduction in the sphincteric function about the urethra, as the muscle that keeps the bladder closed is weakened (Smith 1989a; Smith 1989b; Snooks 1984).

Description of the intervention

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is the mainstay of conservative (non‐surgical) treatment for stress incontinence. This is based on the premise that identification or strength training, or both, of the pelvic floor muscles will counteract weakness by increasing support for the urethra and bladder, and improve the muscle's sphincteric action around the urethra. It has been shown that women with mild or moderate SUI may improve their ability to hold urine significantly simply by learning how to control the pelvic floor muscle strength that they already have (Miller 1996). Such improvement usually occurs much more quickly (one week) than the time needed to build up pelvic floor muscle strength (months).

Some women, however, have trouble identifying their pelvic floor muscles, and compliance with PFMT is variable (Kegel 1951; Lagro‐Janssen 1994; Walters 1992). In addition, incorrect pelvic floor muscle contractions can make the incontinence worse (Bump 1991). For these reasons, there have been attempts to make it easier for women to train their pelvic floor muscles. One of these methods is to use a set of graded weighted vaginal cones (Peattie 1988b; Plevnik 1985). Theoretically, when a cone is placed in the vagina the pelvic floor muscles need to be contracted to prevent the cone slipping out.

Women are instructed to insert the heaviest cone they can retain while standing and moving around and coughing in an upright position, and, when successful with this, they are asked to try with the next heaviest cone. Generally the instructions are to carry the cone for two sessions of 15 minutes per day, for one month or more.

How the intervention might work

The perceived advantages of the cones over traditional methods of training the pelvic floor muscles include: 1. the exercise is individualised for each woman; 2. less time is needed to teach women to use the cones than to teach pelvic floor muscle training; 3. it doesn't take much time to insert and remove cones; 4. usually only one consultation is needed; 5. the cones provide a form of biofeedback as the sensation of one slipping out induces a pelvic floor muscle contraction which may both strengthen muscles and help to synchronize muscle contraction with increases in abdominal pressure (Deindl 1995); 6. the graded increases in cone weight represent improvement in muscle strength and motivates women to continue; 7. the use of vaginal cones can be self‐taught, and they can be used without supervision and vaginal examination (Wise 1993); 8. cones can be used in self‐instruction of conventional PFMT (Peattie 1988b).

There are, however, theoretical problems with cones. It may not be the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles only that keeps the cones in place (Bø 1995). The vagina is not a vertical cylinder, so natural pelvic tilt may help to retain cones, and, indeed, the transverse lie of some cones has been confirmed radiographically (Hahn 1996). Cones may still train the pelvic floor muscles, but the actual force that needs to be balanced by a pelvic floor muscle contraction will depend upon the angle of an individual's vagina. Thus the weight of cone that is able to be retained may not be a good measurement of pelvic floor muscle strength. Holding a cone in place may well not generate multiple contractions of the pelvic floor muscles, and thus may not be the best option for increasing their strength. Also, physically it is not possible for some women to use cones ‐ for reasons such as having a narrowed, scarred vagina. Their effectiveness is likely to vary depending on, for example, motivation and initial pelvic floor muscle strength (with those having low strength having the most to gain) as well as individual acceptability of the method.

Why it is important to do this review

At the moment there is uncertainty about the best way of treating SUI, so there is a need for systematic reviews examining different treatments. This is one of several reviews looking at conservative treatment for the condition. Others look at pelvic floor muscle training (Dumoulin 2010; Hay‐Smith 2011; Herderschee 2011), and there is a protocol (ongoing review) that will investigate electrostimulation (Gameiro 2012).

Objectives

The objective of this review is to determine the effectiveness of vaginal cones in the management of female urinary stress incontinence (SUI).

We wished to test the following comparisons in the management of stress incontinence: 1. vaginal cones versus no treatment; 2. vaginal cones versus other conservative therapies, such as PFMT and electrostimulation; 3. combining vaginal cones and another conservative therapy versus another conservative therapy alone or cones alone; 4. vaginal cones versus non‐conservative methods, for example surgery or injectables.

Secondary issues which were considered included whether: 1. it takes less time to teach women to use cones than it does to teach the pelvic floor exercise; 2. self‐taught use is effective; 3. the change in weight of the heaviest cone that can be retained is related to the level of improvement; 4. subgroups of women for whom cone use may be particularly effective can be identified.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Women whose predominant complaint is stress urinary incontinence (SUI), diagnosed either by symptom classification or urodynamics.

Types of interventions

One arm of the study must have included the use of weighted vaginal cones following a standardised (within trial) protocol.

Comparators could include other conservative treatments such as pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) or electrostimulation, or surgery, injectables etc.

Types of outcome measures

1. Patient symptoms ‐ perception of cure and improvement of urinary incontinence; number of incontinent episodes in 24 hours. 2. Quality of life measures ‐ general health status (e.g. SF36), severity of incontinence, psychosocial measures, impact of incontinence. 3. Physical measures ‐ change in weight of cone retained, perineometry or other measures of pelvic floor muscle strength, pad tests with measured leakage, ultrasound or radiographic measures of bladder neck descent and mobility. 4. Health economics ‐ cost of interventions, resource implications of differences in outcome, formal economic analysis (e.g. cost effectiveness, cost utility), teaching time.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed for the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Group's Specialised Register of controlled trials, which is described under the Incontinence Group's module in The Cochrane Library. The register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, CINAHL, and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Date of the most recent search of the Specialised Register for this review: 19 September 2012.

The trials in the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The terms used to search the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are given below:

({DESIGN.CCT*} OR {DESIGN.RCT*}) AND {INTVENT.PHYS.CONES}

(All searches were of the keyword field of Reference Manager 12, Thomson Reuters).

For this review additional searches were performed by one of the review authors. These are detailed below.

The following search terms were used in both MEDLINE (January 1966 to March 2013) and EMBASE (January 1988 to March 2013): vaginal and (cones or weights or balls), in both titles and abstracts.

A search for trial authors was also performed in both MEDLINE (January 1966 to Present) and EMBASE (January 1988 to Present) to locate extra reports for included trials. We last performed these searches in February 2013. Extra reports were found for both the Pieber and Cammu trials (Cammu 1998; Pieber 1995).

Searching other resources

The reference lists of relevant articles were searched for other possible relevant trials.

We did not impose any language or other restrictions on the articles that were found.

Data collection and analysis

Any differences of opinion related to study inclusion, methodological quality or data extraction were resolved by discussion with a third party.

Selection of studies

We assessed titles and abstracts of trials identified by the search. We recovered full‐text versions for those considered potentially eligible, and at least two review authors checked eligibility. We excluded trials that were not randomised or quasi‐randomised trials for incontinent patients. Excluded trials are listed, with reasons for their exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Data were abstracted by the lead author and cross‐checked by the co‐author(s). In instances where data might have been collected but not reported, further clarification was sought from the authors of the trials. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Higgins 2011). The pad tests used in the different studies varied dramatically from a 30‐second stress test to a 24‐hour test. In order that these could be combined, the different tests were dichotomised into improvement/no improvement, sometimes requiring the help of authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both review authors independently assessed reports of trials under consideration for inclusion in the review for their methodological quality and appropriateness, without prior consideration of their results. The review authors made an independent assessment of methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration 'Risk of bias' tool, which includes quality of random allocation and concealment, description of dropouts and withdrawals, analysis by intention‐to‐treat, and 'blinding' during treatment and at outcome assessment.

Measures of treatment effect

Rate ratios (RR) were used for dichotomous data and mean differences (MD) for continuous data. 'Leakage episodes' is a count data outcome with a low mean, thus the data are likely to be positively skewed, but, despite this, means and standard deviations were used where possible.

Unit of analysis issues

No unit of analysis issues were found. Cross‐over trials are unlikely to be conducted, but cluster randomised trials might be possible, for example in aged care.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors requesting data when data, such as standard deviations, were missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed by means of visual inspection of the forest plot, the test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

There were too few studies to make funnel plots clearly interpretable, or to place any reliance on small sample bias statistics.

Data synthesis

Data were combined when possible, using rate ratios (RR) for dichotomous data and mean differences (MD) for continuous data. A fixed‐effect analysis was used to calculate the pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Trial data were sub‐grouped by type of incontinence ‐ either genuine stress incontinence based on a urodynamic diagnosis, or stress incontinence based upon a symptom classification. Other subgroup analyses, e.g. for type of electrostimulation, were not possible due to the small number of trials in each comparison.

Sensitivity analysis

It was not possible to conduct potential sensitivity analyses for methodological quality due to the small number of trials in each comparison.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

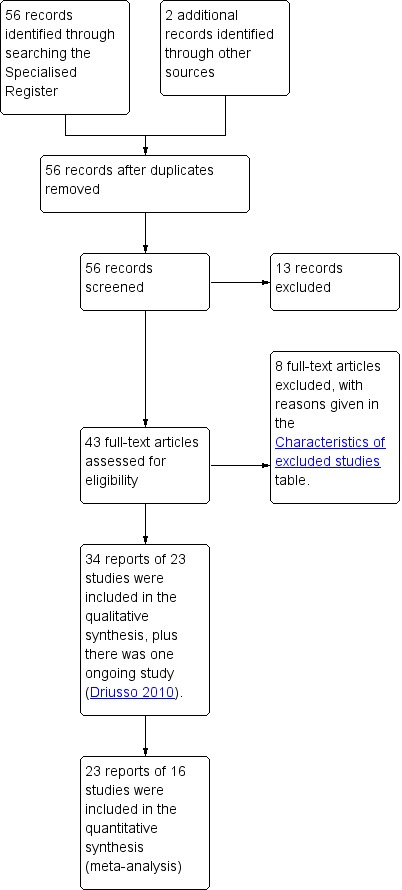

This update, performed in 2013, found six extra trials to add to this review (Arvonen 2002; Castro 2008; Gameiro 2010; Harvey 2006; Pereira 2012; Santos 2009), in addition to the one added in 2007 (Williams 2006), and one ongoing trial (Driusso 2010). This means that we identified a total of 23 trials that compared the use of vaginal cones with a comparison group. A further five studies were excluded (see below). The literature assessment process is documented with a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Included studies

In total, twenty‐three trials were included in this review. Seven of these were reported only as abstracts from conferences (Bourcier 1994; Burton 1993; Haken 1991; Harvey 2006; Peattie 1988a; Terry 1996; Wise 1993), so reported limited results and details of the methods. One of the trials was still in progress when the abstract was written, so did not report complete results, and no further report has been identified (Peattie 1988a). Extra, unpublished information was provided by the authors for five trials (Arvonen 2001; Bø 1999; Peattie 1988a; Williams 2006; Wilson 1998).

Details of cone protocols

Most of the cones groups in the trials used the same protocol, which was, after the initial training, to hold the cone in place for two sessions of 15 minutes per day. All but one of the trials that did not use this particular protocol used very similar ones:

Laycock 1993 used two times per day for 10 minutes each;

Laycock 2001 used one time per day for 10 minutes;

Pieber 1995 used one time per day for 15 minutes;

Arvonen 2001 and Arvonen 2002 asked women to exercise while holding the weighted balls two times a day and to carry the weight for one session of 15 minutes.

One trial was quite different (Seo 2004): it used a different type of cone, varied the weight by asking that the degree of reclining was varied, and instructed women to contract the pelvic floor muscles around the cone. So, with the exception of the Seo trial, the cones treatments were relatively homogeneous.

Types of cones

The cone treatments used differed in the number of different weights available and the shape of the cones. Some of the trials used sets of cones with different numbers of weights:

seven used nine weights (Castro 2008; Laycock 1993; Olah 1990; Peattie 1988a; Santos 2009; Williams 2006; Wilson 1998);

seven used five weights (Cammu 1998; Delneri 2000; Haken 1991; Gameiro 2010; Pereira 2012; Pieber 1995; Wise 1993);

one had three weights (Bø 1999);

and one trial used only one weight (Terry 1996).

One trial added a variable amount of weights to the cone (Laycock 2001).

Two other trials used balls instead of cones (Arvonen 2001; Arvonen 2002), with two weights used at a time, one when static and one when moving around: weights were increased halfway through treatment. Three trials used cones with an unknown number of weights (Bourcier 1994; Burton 1993; Harvey 2006). One trial used a single weight of cone, but in a sitting position, with the angle to which the back was reclined directly related to the weakness of the pelvic floor (Seo 2004). Most cones were conical at one end, but two trials used cylinders with rounded ends (Bø 1999; Terry 1996), one used a cone with a waist that was gripped by the pelvic floor (Seo 2004), and two others used weighted balls (Arvonen 2001; Arvonen 2002).

Comparator interventions

The comparison groups used a wide range of treatments. These have been grouped for the purposes of this review, so that all PFMT treatments were treated alike, as were the electrostimulation treatments. Electrostimulation is electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor, which is carried out in a wide variety of ways and is the subject of another Cochrane review that is in preparation (Gameiro 2012).

The authors of another Cochrane systematic review on pelvic floor muscle training found that low intensity training was not as effective as higher intensity training, but there were few other differences, including no evidence of extra benefit from biofeedback (feedback of biological information while undergoing treatment) (Hay‐Smith 2006). In all the trials included in this review, the PFMT regimes would be considered as being of higher intensity. Other reviews may show whether combining different electrostimulation treatments is appropriate or not.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures that were used varied between trials. Many of the prespecified outcomes were reported by only one trial. Sometimes continuous outcomes were reported as differences from baseline, and sometimes the final values were presented. Standard deviations were often missing.

Subjective outcomes were worded and grouped differently, and urinary diaries were collected for different lengths of time with different measures reported. There were many different types of pad test. Two trials used both a short pad test and a 24‐hour pad test (Bø 1999; Williams 2006). Only the results from the short pad test were used in the formal comparisons, as this was more similar to the other pad tests used.

While perineometry (measurement of the strength of voluntary muscle contractions in the perineum) was usually measured in cm of water, the devices used were different and of unknown comparability. One trial used mm of mercury (Seo 2004).

The time at which the outcome was measured relative to the start and end of treatment was another characteristic that varied widely between trials. This is important because it is likely that some decrease in effectiveness will occur after the end of treatment.

One trial presented means as pad test results with no indication of the variation present (Terry 1996). As this was not comparable with the results of other trials these data have been omitted from the formal comparisons. This trial compared cones with electrostimulation plus PFMT, which is one of the less useful comparisons for practitioners, as electrostimulation and PFMT are seldom combined as they were in this trial.

Types of participants and types of incontinence

One trial recruited pre‐menopausal women (Pieber 1995), and one post‐menopausal women (Pereira 2012), while another recruited women at three months postpartum (Wilson 1998).

Most trials recruited women with urodynamically‐proven genuine stress incontinence with few other inclusion or exclusion criteria. In seven trials, symptoms of stress incontinence were sufficient for women to be included (Arvonen 2001; Arvonen 2002; Gameiro 2010; Laycock 2001; Olah 1990; Pereira 2012; Wilson 1998), but in one study it was unclear what inclusion criteria had been used (Seo 2004).

Excluded studies

Eight trials were excluded from the review for a variety of reasons. Two of them examined the use of cones for primary prevention, and had recruited women who were not incontinent and thus did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review (Jonasson 1989; Norton 1990). One, when translated, was deemed not to be a randomised trial (Salinas Casado 1999); another randomised women with urgency rather than stress incontinence (Lentz 1994); one did not randomise women to cone therapy (Williams 2005); and one assigned women to groups on the basis of geographic proximity to a hospital, so was not a randomised trial (Parkkinen 2004). In this update two trials were added to those excluded, one was a systematic review (Ferreira 2011), and one a trial of a resistance device to train the pelvic muscles (Delgado 2010).

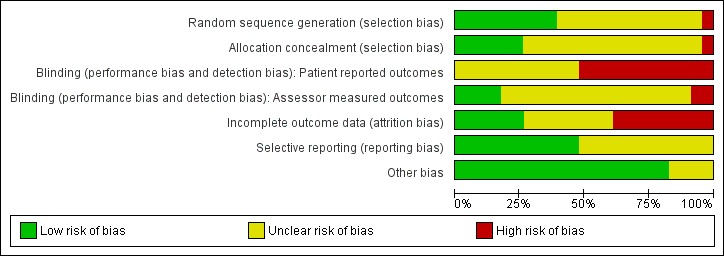

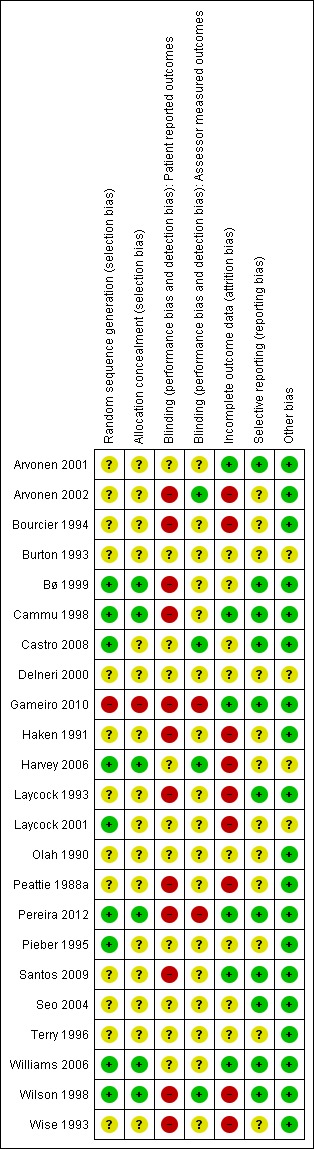

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of the included trials is presented in Figure 2; and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Due to the brevity of the reporting it was particularly difficult to assess the quality of the seven trials that were published in abstract form only (Bourcier 1994; Burton 1993; Haken 1991; Harvey 2006; Peattie 1988a; Terry 1996; Wise 1993).

Allocation

Only five of the 23 included trials reported blinded group allocation (Bø 1999; Harvey 2006; Pereira 2012; Williams 2006; Wilson 1998); the other eighteen did not give enough information to allow this to be assessed, and one appeared to be a quasi‐randomised trial that used alternation (Gameiro 2010).

Blinding

With physical therapies such as cones it is impossible to blind the participants to the treatment they are getting.

Much of the assessment was done by means of questionnaires completed by participants. Only two trials reported that blinded assessors were used for other measures (Bø 1999; Wilson 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

All trials analysed women in the group to which they had been assigned. However, some trials had a high proportion of withdrawals, for many of whom there were no outcome data. Two trials reported treatment‐related dropout (Cammu 1998; Wilson 1998), with the Cammu trial having many more dropouts in the cones group than the comparison group, while Wilson had a high proportion of dropouts in all three treatment groups, and a moderately high proportion of dropouts in the control group.

Selective reporting

While there is the usual incomplete reporting of, especially, continuous outcomes, there is no evidence that there were outcomes that were measured but remained unreported. Many of the studies made no mention of having recorded urinary (or bladder) diaries, which is the usual way of measuring the number of urine leakages, so would be considered an important outcome for women included in these trials.

Other potential sources of bias

The trials were small, so were more susceptible to outliers, and publication bias. Only two trials randomised more than 60 women to treatment with cones (n = 74, 36 cones alone and 38 PFMT plus cones, Wilson 1998; and n = 80, Williams 2006). The other cones groups ranged in size from 10 to 60.

Effects of interventions

1. Cones versus controls

Five trials compared cones with control treatment, which was defined as no active management aimed at exercising the pelvic floor (Bø 1999; Castro 2008; Pereira 2012; Williams 2006; Wilson 1998). In none of these trials was the control arm a no treatment arm.

In one, the women in the control group were offered the use of a vaginal device, the Continence Guard (Coloplast AG), and about half of them used this (Bø 1999).

In another, the controls were asked to continue with their "normal" postnatal PFMT regime (Wilson 1998).

In three trials the controls received a leaflet explaining the pelvic floor and describing pelvic floor muscle exercises (Castro 2008; Pereira 2012; Williams 2006)

In two there was extra contact with a nurse (Castro 2008; Williams 2006).

The populations of women recruited into these trials were different:

Bø, Castro and Williams recruited women with urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence (Bø 1999; Castro 2008; Williams 2006);

while Pereira and Wilson recruited women with symptoms of incontinence three months postpartum (Pereira 2012; Wilson 1998).

There was little overlap in the outcome measures collected.

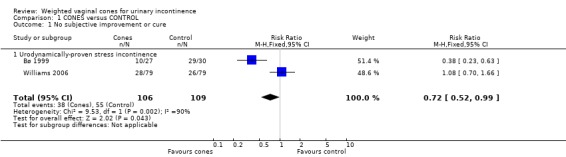

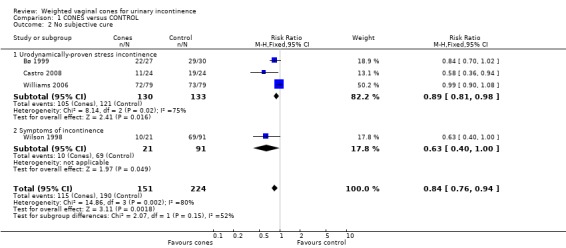

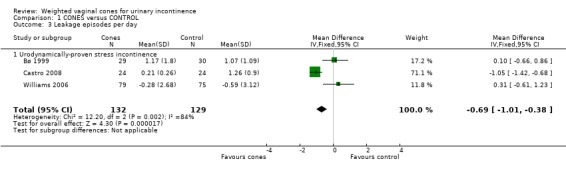

Treatments with cones were better than control treatments in the subjective reporting of cure or improvement (risk ratio of failure to cure or improve (RR) 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 0.99) (Analysis 1.1), and lack of cure (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.94) (Analysis 1.2). For one of the included trials (Bø 1999), the numbers with "mild or no problem" were used to imply "cure or improvement". There was a small improvement in leakage episodes (mean difference 0.69, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.01) (Analysis 1.3), but there were no statistically significant differences for pad test, or pelvic floor muscle strength, and the confidence intervals were generally wide.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CONES versus CONTROL, Outcome 1 No subjective improvement or cure.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CONES versus CONTROL, Outcome 2 No subjective cure.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CONES versus CONTROL, Outcome 3 Leakage episodes per day.

In addition to the prespecified outcomes, Bø reported that cones were better than control for the leakage index (Bø 1999). There were no statistically significant differences on the 24‐hour pad test, the social activity index, whether participants wanted further treatment, or whether the incontinence was problematic. Pereira reported that cones were better on two domains of the Kings Health Questionnaire (Pereira 2012), and Castro reported improved quality of life using the Urinary Incontinence Quality of Life scale (I‐QoL) (Castro 2008).

2. Cones versus PFMT

Thirteen trials compared cones with PFMT (Arvonen 2001; Arvonen 2002; Bø 1999; Cammu 1998; Castro 2008; Gameiro 2010; Haken 1991; Harvey 2006; Laycock 2001; Peattie 1988a; Pereira 2012; Williams 2006; Wilson 1998). There was limited overlap with the outcome measures, and all the regimens of PFMT were different.

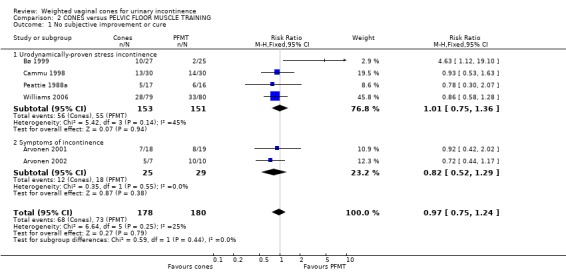

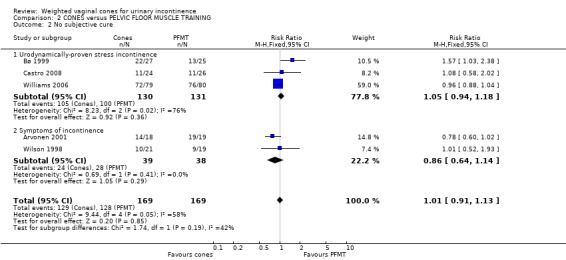

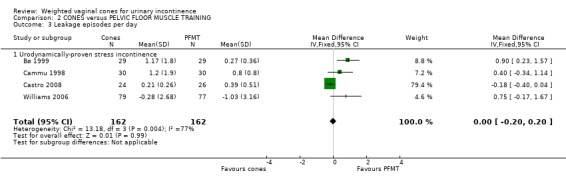

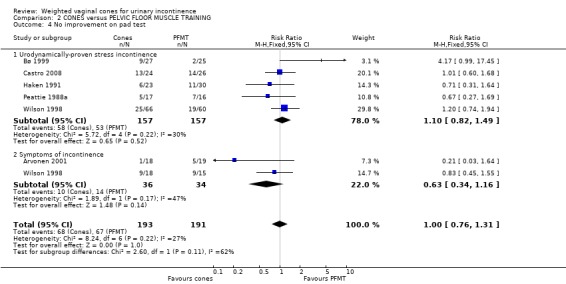

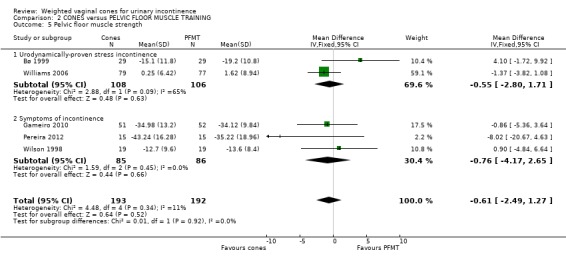

There were no statistically significant differences in subjective improvement or cure (reported in six trials) (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.24) (Analysis 2.1); subjective cure (reported in five trials) (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.13) (Analysis 2.2); leakage episodes per day (reported in four trials) (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.20) (Analysis 2.3); no improvement in pad test (reported in six trials) (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.31) (Analysis 2.4); or in pelvic floor muscle strength (reported in five trials) (mean difference (MD) ‐0.61, 95% CI ‐2.49 to 1.27) (Analysis 2.5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 1 No subjective improvement or cure.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 2 No subjective cure.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 3 Leakage episodes per day.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 4 No improvement on pad test.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 5 Pelvic floor muscle strength.

In addition to the prespecified outcomes:

Arvonen reported a difference in median grams of leakage in favour of vaginal balls, and no statistically significant difference in pelvic floor muscle strength (Arvonen 2001);

Bø reported that cones were worse than PFMT for the leakage index, and more of the cones group wanted further treatment, but there were no statistically significant differences on the other extra outcomes (24‐hour pad test, social activity index, and whether the incontinence was problematic) (Bø 1999);

Cammu found no statistically significant differences between cones and PFMT for pads per week, visual analogue scales (VAS) for incontinence and distress, or whether patients requested surgery after the treatment period (Cammu 1998);

Laycock found no statistically significant differences in quality of life assessed using the King's Health Questionnaire, pad usage, wet episodes or muscle contractibility, but standard deviations were not reported, so these data could not be added to the formal comparisons (Laycock 2001);

Peattie found no statistically significant difference in the proportion referred to surgery at the end of treatment (Peattie 1988a);

Castro reported no difference in I‐QoL scores (P value 0.65, Castro 2008);

Harvey reported no statistically significant difference in either the Urinary Distress Inventory (UDI‐6) or I‐QoL (Harvey 2006);

Pereira reported no statistically significant differences in three domains of the Kings Health Questionnaire.

3. Cones versus electrostimulation

Six trials compared cones with electrostimulation (Bø 1999; Castro 2008; Delneri 2000; Olah 1990; Santos 2009; Wise 1993). The electrostimulation regimens were quite different from each other. Olah taught women in both arms of the trial to contract their pelvic floor muscles and encouraged them to do this regularly (Olah 1990).

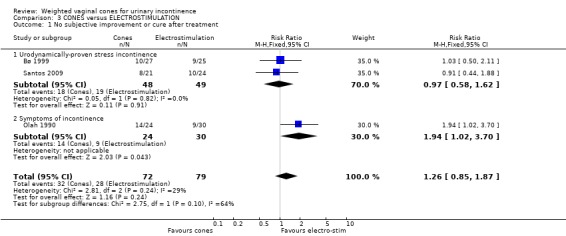

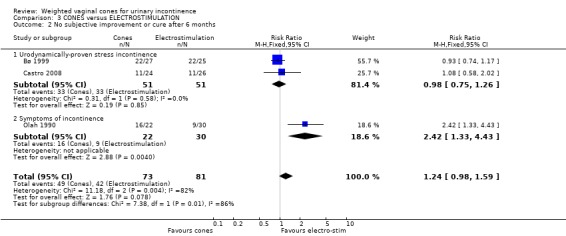

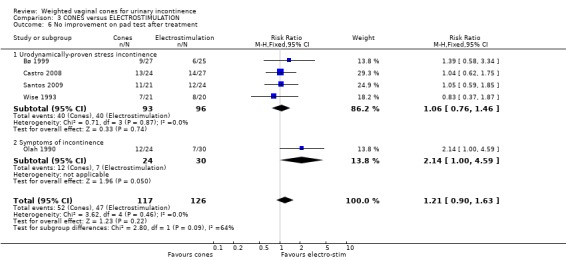

No statistically significant differences emerged between cones and electrostimulation in respect of the prespecified outcome measures, improvement (RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.87) (Analysis 3.1); subjective cure (measured in three trials) (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.59) (Analysis 3.2); improvement in pad test (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.63) (Analysis 3.6); leakage of urine, or pelvic floor muscle strength. Again, confidence intervals were generally wide, so the results were consistent both with cones being better than electrostimulation and with cones being worse than electrostimulation.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 1 No subjective improvement or cure after treatment.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 2 No subjective improvement or cure after 6 months.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 6 No improvement on pad test after treatment.

In addition, Bø found no statistically significant differences between electrostimulation and cones on all the extra outcomes used: the social activity index, the 24‐hour pad test, the leakage index, the proportion of participants wanting further treatment, and those rating their incontinence as unproblematic (Bø 1999). Delneri found no statistically significant difference in a VAS recording overall discomfort (Delneri 2000).

4. Cones plus PFMT versus PFMT

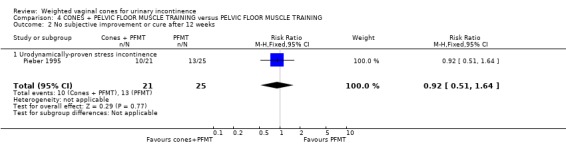

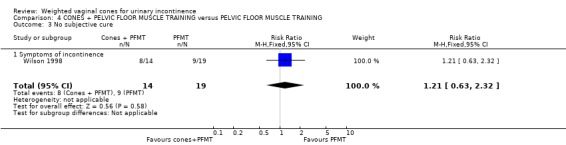

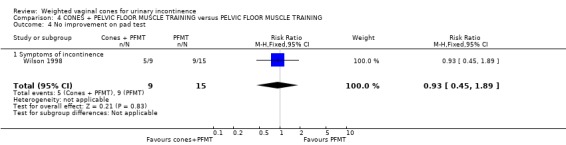

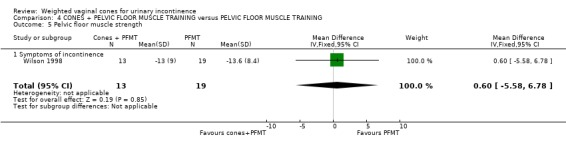

Cones plus PFMT were compared to PFMT alone in two trials (Pieber 1995; Wilson 1998). None of the outcomes used in these two trials overlapped. No statistically significant differences were detected in outcome measures in either trial, and confidence intervals were all wide. In addition to the prespecified outcomes, Pieber found no statistically significant differences in urodynamic parameters (Pieber 1995).

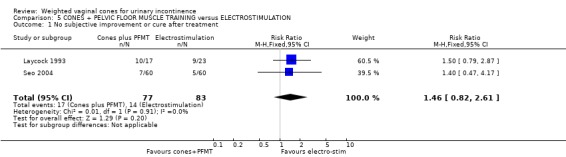

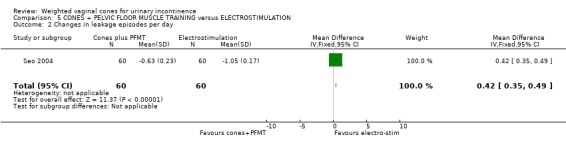

5. Cones plus PFMT versus electrostimulation

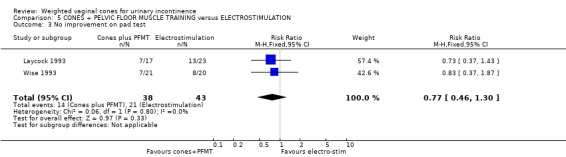

Three trials compared cones plus PFMT with electrostimulation (Laycock 1993; Seo 2004; Wise 1993). Improvement on the pad test was the only common outcome (used in two trials). There was no statistically significant difference in this respect (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.30) (Analysis 5.3), nor in any other outcome.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 3 No improvement on pad test.

Seo found no statistically significant differences between groups for pad tests, maximal vaginal pressure, maximal urethral close pressure, duration of pelvic floor muscle contractions, daytime frequency, amount of urine leakage, difficulty in doing exercises due to incontinence, sexual life, daily life, avoiding places, difficulty in personal relationships, or quality of life (Seo 2004).

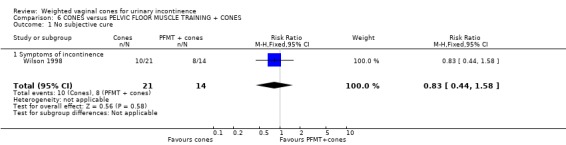

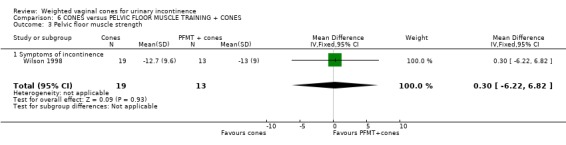

6. Cones versus cones plus PFMT

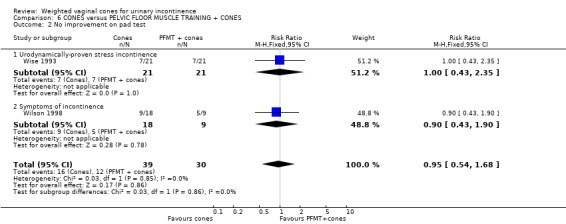

Cones alone were compared with cones plus PFMT in two trials (Wilson 1998; Wise 1993). Neither of these trials identified any statistically significant differences between the groups, but all confidence intervals were wide. The only outcome the two trials had in common was improvement on pad testing (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.68) (Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING + CONES, Outcome 2 No improvement on pad test.

7. Cones versus PFMT plus electrostimulation

In a comparison of cones versus PFMT plus electrostimulation, Terry reported no statistically significant difference in pad tests at six weeks or six months, and no statistically significant differences in the proportions willing to continue treatment (Terry 1996).

8. Cones versus non‐conservative treatments

There were no trials that addressed this comparison.

9. Different methods of using cones

One trial compared active versus passive use of cones (Burton 1993). For passive use, the cones were simply held in the vagina, but for active use the women carried out a standard series of activities while holding the cones. There were no statistically significant benefits of the active treatment. The only outcome reported that could be used was no leakage after coughing with active compared to passive treatment, a RR of 0.72 (95% CI 0.36 to 1.42) (21/30 (70%) versus 18/31 (58%)).

10. Other considerations

i. Other comparisons

One trial compared PFMT plus cones with electrostimulation plus PFMT with biofeedback (Bourcier 1994). It was difficult to classify this trial into any of the above comparisons. There were no statistically significant differences reported between the two treatments.

ii. Quality of life

Seven trials reported on quality of life (Burton 1993; Castro 2008; Harvey 2006; Laycock 2001; Pereira 2012; Santos 2009; Seo 2004), and, even though the same questionnaire was used in three trials (Castro 2008; Harvey 2006; Santos 2009), no standard deviations for the scores were reported, so they could not be combined. Four trials in this 2013 update reported similar improvements in the quality of life scores in all of the treatment groups (cones, electrostimulation, pelvic floor muscle training) when compared to the controls (Castro 2008; Harvey 2006; Pereira 2012; Santos 2009). There were no reported differences between these differing interventions and the quality of life improvements. For the other trials, Seo used a five‐point Likert scale (Seo 2004), and Bø reported a social activity index which may be related to quality of life (Bø 1999). Bø and Burton both reported a leakage index (Bø 1999; Burton 1993). Wilson also reported measures of sexual satisfaction, which did not differ significantly between treatment groups (Wilson 1998).

iii. Economic measures

No trial reported economic measures. One trial reported teaching time and found no statistically significant difference between teaching the use of cones and the teaching of PFMT (Wilson 1998). Peattie assigned shorter teaching times to the cones group and found no statistically significant difference between it and the PFMT group (Peattie 1988a), while Wise simply gave verbal instruction in the use of cones (Wise 1993).

iv. Method of instruction

Most trials taught the use of the cones and how to do a pelvic floor muscle contraction but Wise gave only verbal instruction (Wise 1993). The results in this trial did not differ from those in which the women received more comprehensive instruction.

v. Sensitivity analysis

It was decided that no sensitivity analyses were possible to explore the effects of methodological quality due to the uniformity of the quality and the lack of similar, combinable, outcomes in most of the trials.

vi. Acceptability of treatment/dropouts

One‐hundred and fifty‐nine of the 717 women (22%, range 0 to 72%) treated with cones withdrew or dropped out during treatment. For treatment with cones only, the number of dropouts was 94 out of 482 women (20%, range 0 to 47% with one study 72%). Treatment with cones plus PFMT resulted in 65 out of 175 women dropping out of treatment (37%, range 24% to 63%). In the comparison treatments the numbers of dropouts were 34 out of 209 (16%) for the control treatments, 82 out of 383 (21%) for the PFMT only treatments and 20 out of 135 (15%) for those receiving electrostimulation. In addition, Terry 1996 had 19 out of 30 (63%) of women drop out of treatment with PFMT and electrostimulation. Few trials examined the reasons for women dropping out of treatment, but those that did gave reasons that included motivation problems, unpleasantness, aesthetic dislike, discomfort, bleeding, and vaginal prolapse. None of these seemed to be predominant.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The limited evidence available suggests that cones benefit women with stress urinary incontinence compared to no active treatment. Cones appear to be similar to both PFMT and electrostimulation in its various forms. Using cones in conjunction with PFMT appeared to produce no extra benefit, and the results were statistically compatible with both better, and worse, performance.

As a result of few trials addressing each comparison, combined with the small size of the trials, there are wide confidence intervals around many of the results. To put this another way, for most of the comparisons the data are compatible both with cones being clearly worse or clearly better than the comparison treatment, so the place of cones in the treatment of SUI cannot be determined accurately with the data currently available to us.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The protocols for treatment with cones were relatively standard, but the number of different weights of cones used, as well as the differences between two successive cone weights, varied among the trials. Most trials used five or more cones with weight differences of 12.5 g or less. One trial used three cones with weight differences of 20 g and 30 g (Bø 1999). Some of the cones were of a different shape to the others (Arvonen 2001; Arvonen 2002; Bø 1999; Seo 2004; Terry 1996), and three trials used a shorter duration of treatment (Laycock 1993; Laycock 2001; Pieber 1995). Arvonen used weighted balls, with the same two weights for all women, but used different weights for different exercises (Arvonen 2001; Arvonen 2002). The weights were increased halfway through the treatment. While these differences could theoretically affect the treatment, there were no trials comparing treatment with different types of cone so no direct comparisons could be made. A comparison across trials did not show any obvious differences.

The treatments within the comparison groups varied widely, to the extent that there is some doubt about the validity of combining them. The PFMT regimes required different numbers of daily contractions; some women were instructed to do fast and slow contractions while some were not; there were different training times; and different amounts of contact with a therapist. Some trials provided limited details of the regimens. There is some experimental evidence that certain PFMT regimens are better than others (Hay‐Smith 2006). The intensity of PFMT may have been greater in some trials, such as Bø 1999. This may have affected the relative performance of the interventions, but the data were too few to test for interaction between treatment effect and subgroups of trials. Electrostimulation also varied, with differences in location of stimulation (internal or external), the electrical frequencies used, and the length of each treatment. Internal stimulation was carried out daily at home (Bø 1999; Wise 1993), or in the clinic (Delneri 2000), whereas external stimulation was delivered at the clinic several times a week (Laycock 1993; Olah 1990; Seo 2004). Again, these differences could alter the effectiveness of electrostimulation, but it was not possible to address this issue in this review.

There was no direct comparison of different ways of teaching the use of the cones. It might be possible to use cones successfully without much in the way of teaching. Wise gave only verbal instruction, similar to those written on the instructions that come with the cones, and achieved results that did not differ from those in trials with more teaching time (Wise 1993). There was also no significant effect from teaching active versus passive use of the cones (Burton 1993).

Quality of the evidence

All trials were small with the largest randomising only 80 women to the use of cones (Williams 2006).

Many of the trials had considerable numbers of withdrawals, in spite of efforts to include all participants in the analysis. Some of the trials commented on the drop‐out rate of women from the groups using cones. Some mentioned that few women wanted to continue with them after the treatment period, although others did wish to do so. The drop‐out rate was roughly similar in most of the groups within each trial, with only one trial having a markedly higher rate in the cones group compared to the comparison group (Cammu 1998). In some cases, for physical reasons, treatment with cones may be difficult, and some women appear to find them unpleasant to use.

The interpretation is hindered by problems with the trials. Usually the reporting was poor, with much crucial information missing. Seven of the 23 included trials were reported as abstracts only, and one of these reported only preliminary results. Unpublished information was available for just four of the trials (Arvonen 2001; Bø 1999; Peattie 1988a; Wilson 1998).

Many different outcome measures were reported, which made it difficult to combine results. Often the trials ‐ especially those reported only as abstracts ‐ did not present results for all the outcomes measured. Particular difficulty was encountered with the results of pad testing. Just about every pad test was different, ranging from very short, at 30 seconds, to 24 hours, with variation in conditions such as the fullness of the bladder at the start of the test. Variation in pad testing is a common problem in incontinence research and hinders comparison of treatments (Soroka 2002). The results were also presented differently, with some trials using grams of leakage, some presenting difference pre to post treatment, and some just presenting improvement. The results in grams of leakage were highly skewed, which caused the mean to be a poor measure to use. Pad testing itself is also a fairly unreliable outcome measure, as it has low repeatability. As a result of these problems it was decided to use simple improvement on the pad test as the common outcome, where this was possible. This is not very satisfactory as it does not use much of the information available. Pad testing is discussed further elsewhere (Ryhammer 1999).

The use of pelvic floor muscle strength as an outcome measure is also subject to difficulties, as it is a surrogate outcome of questionable reliability, and its correlation with continence or change in continence is unknown. Different techniques of measuring may give different results. This outcome is included in this review because, if weighted cones do improve continence it is likely to be because they train and strengthen the pelvic floor. Data were sufficiently alike in the two trials that reported this outcome to allow the results to be combined to provide a weighted mean difference. However, there were no significant differences between any of the comparisons which provided these data.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There was some evidence that vaginal cones may be better than no active treatment in women with stress incontinence, with limited evidence that they are similar to other conservative treatments. The 23 trials included in this review reported that between 0% and 72% (average 22%) of women stopped using cones early. These drop‐out rates were similar to those for electrostimulation or pelvic floor muscle training. Cones remain an option that may appeal to some: if conservative therapy is contemplated, then cones could be offered as one option for training the pelvic floor muscles, in the hope that one type of training is acceptable.

Implications for research.

The place of cones in the physical treatment of stress incontinence is yet to be decided. This review has not been able to rule out that there may be clinically significant differences between different conservative methods of treating stress incontinence. Larger, well conducted trials need to be carried out. These should have a standard, minimum set of outcomes that are easy to report and combine with other trials. These outcomes should include: a subjective report of cure or improvement measured on a five‐point scale; a standardised pad test, reported as improvement on the test or improvement by more than a given amount as well as grams of leakage; quality of life measures; economic outcomes; and possibly a test of pelvic floor muscle strength. These should be measured after a suitable duration of treatment (at least long enough to be able to affect muscle that has been damaged in some way) and some time after that to see if any changes persist. The purpose of treatment is to provide long‐term continence, so outcomes should be measured at least at six months, and preferably one year, after treatment. Prior to randomisation, it may be worthwhile having a run‐in period of treatment with cones for both the cones and comparison group(s) to establish which methods are acceptable.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 May 2013 | New search has been performed | Six new trials added |

| 14 May 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Six new trials added |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 7 November 2007 | New search has been performed | Updated Issue 1, 2008 McGrouther et al has been removed from the pending studies as it has now been published as Williams 2006 and is included. Williams 2005 is excluded as it does not report on cone therapy. Jill Mantle is no longer an author as she has now retired completely. |

| 8 February 2006 | New search has been performed | Updated Issue 2, 2006 The third update of the review (Dec 2005) includes the following: The authorship has changed. Stan Plevnik is no longer an author. Nicola Dean has been added to the authors. One extra study has been added to the excluded studies list (Parkkinen 2004), and one to the included studies (Seo 2004). This has not changed the conclusions at all. |

| 14 August 2003 | New search has been performed | Issue 4 2003 Search updated July 2003: no new eligible studies found. |

| 14 November 2002 | New search has been performed | Updated Issue 1, 2002 This updated review includes the results of five extra studies, three new ones (Arvonen 2001; Delneri 2000; Laycock 2001) and two abstracts from conference proceedings that have only been identified since the review was first written (Bourcier 1994; Burton 1993). These studies did not change the conclusions for several reasons. Some evaluated new comparisons, most were small, and inadequate reporting meant that some outcomes could not be used. |

| 30 August 2001 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Stan Plevnik for his co‐authorship of the first two versions of this review, and Jill Mantle for her co‐authorship on the first three versions of the review.

Thanks to Jean Hay‐Smith for useful discussions on the form of the review and comments on the draft review. We would like to thank Tiina Arvonen, Kari Bø and Alison Peattie for the provision of unpublished data.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CONES versus CONTROL.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No subjective improvement or cure | 2 | 215 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.52, 0.99] |

| 1.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 2 | 215 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.52, 0.99] |

| 2 No subjective cure | 4 | 375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.76, 0.94] |

| 2.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 3 | 263 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.81, 0.98] |

| 2.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.40, 1.00] |

| 3 Leakage episodes per day | 3 | 261 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.69 [‐1.01, ‐0.38] |

| 3.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 3 | 261 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.69 [‐1.01, ‐0.38] |

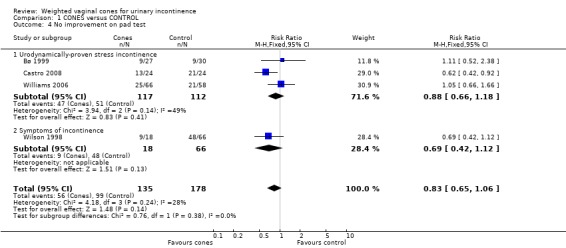

| 4 No improvement on pad test | 4 | 313 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.65, 1.06] |

| 4.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 3 | 229 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.66, 1.18] |

| 4.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.42, 1.12] |

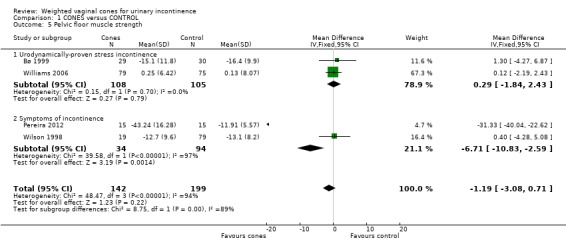

| 5 Pelvic floor muscle strength | 4 | 341 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.19 [‐3.08, 0.71] |

| 5.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 2 | 213 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [‐1.84, 2.43] |

| 5.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 2 | 128 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.71 [‐10.83, ‐2.59] |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CONES versus CONTROL, Outcome 4 No improvement on pad test.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CONES versus CONTROL, Outcome 5 Pelvic floor muscle strength.

Comparison 2. CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No subjective improvement or cure | 6 | 358 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.75, 1.24] |

| 1.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 4 | 304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.75, 1.36] |

| 1.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 2 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.52, 1.29] |

| 2 No subjective cure | 5 | 338 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.91, 1.13] |

| 2.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 3 | 261 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.94, 1.18] |

| 2.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 2 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.64, 1.14] |

| 3 Leakage episodes per day | 4 | 324 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.20, 0.20] |

| 3.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 4 | 324 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.20, 0.20] |

| 4 No improvement on pad test | 6 | 384 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.76, 1.31] |

| 4.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 5 | 314 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.82, 1.49] |

| 4.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 2 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.34, 1.16] |

| 5 Pelvic floor muscle strength | 5 | 385 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.61 [‐2.49, 1.27] |

| 5.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 2 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.55 [‐2.80, 1.71] |

| 5.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 3 | 171 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.76 [‐4.17, 2.65] |

Comparison 3. CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No subjective improvement or cure after treatment | 3 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.85, 1.87] |

| 1.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 2 | 97 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.58, 1.62] |

| 1.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.94 [1.02, 3.70] |

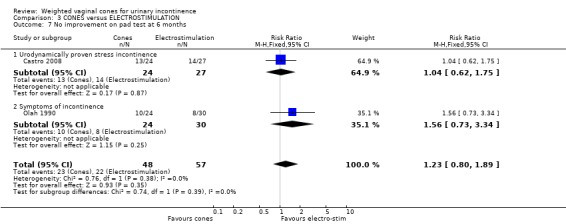

| 2 No subjective improvement or cure after 6 months | 3 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.98, 1.59] |

| 2.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 2 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.75, 1.26] |

| 2.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.42 [1.33, 4.43] |

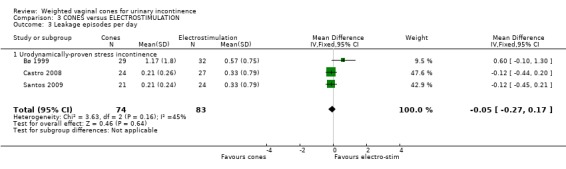

| 3 Leakage episodes per day | 3 | 157 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.27, 0.17] |

| 3.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 3 | 157 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.27, 0.17] |

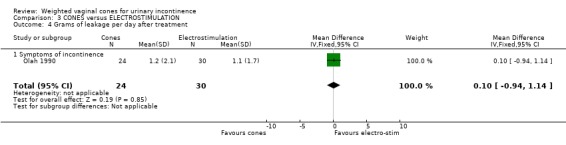

| 4 Grams of leakage per day after treatment | 1 | 54 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.94, 1.14] |

| 4.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 54 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.94, 1.14] |

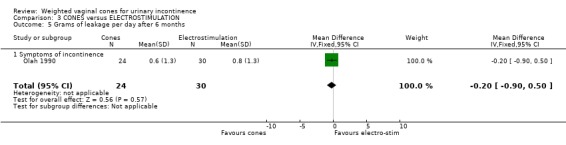

| 5 Grams of leakage per day after 6 months | 1 | 54 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.90, 0.50] |

| 5.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 54 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.90, 0.50] |

| 6 No improvement on pad test after treatment | 5 | 243 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.90, 1.63] |

| 6.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 4 | 189 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.76, 1.46] |

| 6.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.00, 4.59] |

| 7 No improvement on pad test at 6 months | 2 | 105 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.80, 1.89] |

| 7.1 Urodynamically proven stress incontinence | 1 | 51 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.62, 1.75] |

| 7.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.73, 3.34] |

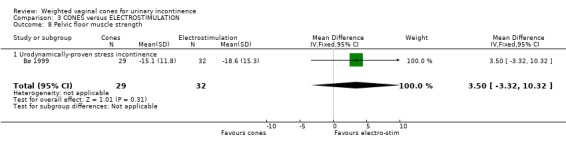

| 8 Pelvic floor muscle strength | 1 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.50 [‐3.32, 10.32] |

| 8.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 1 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.50 [‐3.32, 10.32] |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 3 Leakage episodes per day.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 4 Grams of leakage per day after treatment.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 5 Grams of leakage per day after 6 months.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 7 No improvement on pad test at 6 months.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CONES versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 8 Pelvic floor muscle strength.

Comparison 4. CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

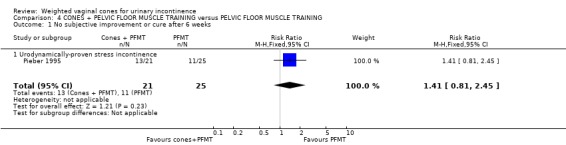

| 1 No subjective improvement or cure after 6 weeks | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.81, 2.45] |

| 1.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.81, 2.45] |

| 2 No subjective improvement or cure after 12 weeks | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.51, 1.64] |

| 2.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.51, 1.64] |

| 3 No subjective cure | 1 | 33 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.63, 2.32] |

| 3.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 33 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.63, 2.32] |

| 4 No improvement on pad test | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.45, 1.89] |

| 4.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.45, 1.89] |

| 5 Pelvic floor muscle strength | 1 | 32 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [‐5.58, 6.78] |

| 5.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 32 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [‐5.58, 6.78] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 1 No subjective improvement or cure after 6 weeks.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 2 No subjective improvement or cure after 12 weeks.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 3 No subjective cure.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 4 No improvement on pad test.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING, Outcome 5 Pelvic floor muscle strength.

Comparison 5. CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus ELECTROSTIMULATION.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No subjective improvement or cure after treatment | 2 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.82, 2.61] |

| 2 Changes in leakage episodes per day | 1 | 120 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.35, 0.49] |

| 3 No improvement on pad test | 2 | 81 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.46, 1.30] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 1 No subjective improvement or cure after treatment.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 CONES + PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING versus ELECTROSTIMULATION, Outcome 2 Changes in leakage episodes per day.

Comparison 6. CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING + CONES.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No subjective cure | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.44, 1.58] |

| 1.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.44, 1.58] |

| 2 No improvement on pad test | 2 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.54, 1.68] |

| 2.1 Urodynamically‐proven stress incontinence | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.43, 2.35] |

| 2.2 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.43, 1.90] |

| 3 Pelvic floor muscle strength | 1 | 32 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐6.22, 6.82] |

| 3.1 Symptoms of incontinence | 1 | 32 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐6.22, 6.82] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING + CONES, Outcome 1 No subjective cure.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CONES versus PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING + CONES, Outcome 3 Pelvic floor muscle strength.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arvonen 2001.

| Methods | 2‐armed RCT. Method of group allocation: not stated. Whether assessor blinded to group allocation: not stated. Duration of treatment was 4 months, final results measured at the end of treatment | |

| Participants | 40 women with symptoms of stress incontinence, age < 65 y, and an understanding of spoken Swedish. Median (range) age was 49 y (32‐64 y) in the vaginal ball group, and 47 y (28‐65 y) in the PFMT group. Parity, BMI, duration of symptoms and score on the Sense of Coherence scale were well matched at randomisation | |

| Interventions | 1. Weighted vaginal balls (n = 20): starting with a ball weighing 65 g, PFMs were squeezed maximally for 20 s, then relaxed for 20 s, with this repeated 10 times. This was done twice daily. In addition, the 50 g ball was retained while moving for 15 min daily. After 2 months the balls were replaced by ones weighing 100 g and 80 g 2. PFMT (n = 20): 10 maximum PFM squeezes while sitting (5‐s squeeze, then 5‐s break) with a short break after 5 squeezes. Repeated while standing. Whole sequence repeated twice daily. In addition, a 3‐s submaximal squeeze followed by a 3‐s rest was repeated 15 times once a day | |

| Outcomes | Short provocation (60 seconds with standard exercises) pad test with a standard 300 ml in bladder Vaginal strength measured by digital palpation. Subjective score on a 4‐point scale (good/fully recovered, improved, no change, worse) | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 2/20 in the vaginal balls group, and 1/20 in the PFMT group. Balls made by Vagitrim, Ipex Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The women were randomized into two groups . . ." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patient reported outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Assessor measured outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome reported on all who were randomised |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No urinary diaries kept |

| Other bias | Low risk | No reason to suspect this |

Arvonen 2002.

| Methods | 2‐armed parallel RCT. Method of group allocation: not clear. Treatment for 4 months | |

| Participants | 24 female participants with stress incontinence. Inclusion criteria were leakage of 1‐12 g, age 30‐65 y and able to understand spoken Swedish. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, cysto/rectocele, prolapse, ongoing vaginal infection and medication affecting urinary tract function. Women had a mean age of 42 y (range 30‐57 y), a mean BMI of 24 (range 19–33), mean number of pregnancies was 2 (range 1–8) and mean duration of symptoms was 6 y (range 1–18 y). | |

| Interventions | The participants visited the clinics 3 times for assessments and twice for learning the training. All participants were instructed in pelvic floor anatomy and function, and their ability to contract their PFM properly was checked on the first visit. Both groups received verbal information and a written programme from a physiotherapist. The group training with vaginal balls also received a set of vaginal balls 1. PFMT (10 completed the study). 10 contractions 4 times a day performed in both sitting and standing positions. Each contraction supposed to last for 5 s followed by 5 s relaxation. In the second week 15 maximal dynamic contractions of 3‐4 s followed by relaxation for 3–4 s and a maximal static contraction for 2 min were added. From the third week the following were also added (all in the supine position with legs bent): contraction‐cough 3 times; contraction pelvic lifting 3 times; and contraction sit‐up 3 times 2. Vaginal balls (7 completed the study). (Vagitrim, 2 with a diameter of 28 mm weighing 50 g and 65 g, and 2 with a diameter of 32 mm weighing 80 g and 100 g). During the first 2 months the two lighter balls were used for training, and in the following 2 months the heavier two were used. Pelvic floor contraction with the heaviest ball was performed standing, with a foot's‐length distance between the feet. A maximal contraction for 20 s held the ball in, followed by 20 s of sitting. This was done 10 times, 4 times a day for a total of 40 contractions. In addition, the lightest ball was used once a day for 30 min while performing activities like walking, doing gymnastics, coughing and lifting |

|

| Outcomes | Provocation pad test (standard bladder volume of 275 ml followed by standard exercises). Pelvic muscle strength measured by vaginal palpation. Patients subjective assessment on a 4‐point ordinal scale, good, improved, no change, worse | |

| Notes | Pilot study. 2/12 in the PFMT group and 5/12 in the vaginal ball group did not complete the study. Data were reported and medians and range, so not usable apart from the ordinal subjective assessment | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The patients were consecutively randomised from the physiotherapists' waiting lists to either conventional pelvic floor training or training with vaginal balls by drawing numbered lots." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The patients were consecutively randomised from the physiotherapists' waiting lists to either conventional pelvic floor training or training with vaginal balls by drawing numbered lots." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patient reported outcomes | High risk | Impossible to blind participants to treatment group |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Assessor measured outcomes | Low risk | "The tests were carried out blind at baseline and after 2 and 4 months." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Drop out was differential with more dropping out of the vaginal ball group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No urinary diaries kept |

| Other bias | Low risk | Unlikely |

Bourcier 1994.

| Methods | 2‐armed RCT. Method of group allocation: not stated. Whether assessor blinded to treatment allocation: not stated. Duration of treatment was 3 months, outcomes were assessed at 6 months from start of treatment. Active period of treatment differed between the 2 arms | |

| Participants | 102 women with urodynamically proven stress incontinence. Mean age was 38 y | |

| Interventions | 1. PFMT + cones (n = 50): 3 months of 20 maximal PF contractions 3 times daily, plus use of unspecified cones twice daily and different exercise with instructor for 30 min once a week. After 3 months encouraged to continue the home treatment 2. Electrical stimulation with biofeedback (n = 52): 6 weeks with 2 x 30‐min sessions/week: 20 min short‐term maximal functional electrical stimulation (parameters unspecified), and 10 min of Electromyography/pressure biofeedback. After 3 months attended clinic weekly | |

| Outcomes | Continence status Unspecified pad test Urodynamics PFM strength and endurance | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 12/50 in PFMT + cones group, and 6/52 in the electrical stimulation + biofeedback group Only abstract published | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "We have performed a prospective randomised study . . . " |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patient reported outcomes | High risk | Not possible |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Assessor measured outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Only completers analysed, moderate withdrawal rate |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear, as only an abstract, no urinary diaries kept |

| Other bias | Low risk | No reason to suspect this |

Burton 1993.

| Methods | 2‐armed RCT. Method of allocation: not stated. Whether assessors blinded: not stated. Duration of treatment not specified, nor the point at which the outcome was measured | |

| Participants | 61 women with urodynamically proven GSI | |

| Interventions | 1. Passive cones (n = 31): 15 min twice daily in a static position with unspecified cones 2. Active cones (n = 30): 15 min twice daily while doing standardised activities that previously caused incontinence. Unspecified cones | |

| Outcomes | Urodynamics Cough till leak 40‐min pad test Visual analogue symptom score Leakage activity index Psychological adjustment to illness scale | |

| Notes | Outcomes reported for all participants Only abstract published | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | ". . . randomised to treatment . . . " |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patient reported outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Assessor measured outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Reported that there were no withdrawals |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Reported on all outcomes specified, but no urinary diaries kept |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Only abstract published |

Bø 1999.

| Methods | 4‐armed RCT. Group allocation was blinded. Assessor was blinded to treatment allocation. Assessment was at 6 months from start of treatment | |

| Participants | 122 women with urodynamically proven GSI. The mean age was 49.5 y (range 24‐70 y) and mean duration of symptoms was 10.8 y (range 1‐45 y) | |

| Interventions | 1. Control (n = 32): offered the use of the Continence Guard (Coloplast AS) 2. PFMT (n = 29): 8‐12 maximum contractions 3 times daily plus 1 group session/week 3. Electrical stimulation (n = 32): maximum intermittent stimulation with MS106 Twin (Vitacon AS), 50 Hz, pulse width 0.2 ms, current 0‐120 mA, 30 min every day 4. Cones (n = 29): 20 min daily. Mabella cones, 3 cylindrical weights: 20 g, 40 g, 70 g | |

| Outcomes | Stress pad test (30 s running on the spot then 30 s of jumping jacks) 24‐hour pad test 3‐day leakage episodes Subjective ratings Leakage index Social activity index Pelvic floor muscle strength | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 2/32 in controls, 4/29 in PFMT, 7/32 electrical stimulation, and 2/29 in the cones group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation schemes stratified by degree of incontinence were constructed for all sites by using computer generated random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Participants within each stratum were randomised by using opaque sealed envelopes . . . " |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patient reported outcomes | High risk | Not possible |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Assessor measured outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Reported by group only |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of omitted outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | No reason to suspect this |

Cammu 1998.

| Methods | 2‐armed parallel RCT. Method of group allocation: not stated. No attempt at blinding assessment. Duration of treatment: 12 weeks, outcome assessed at end of treatment | |

| Participants | 60 women with urodynamically proven GSI. PFMT group had a mean age of 55.9 y (SD 9.5), while the cones group had a mean age of 56.3 y (SD 11.4). Duration of symptoms: 6.7 y (SD 7.2) in PFMT group, and 5.3 y (SD 5.2) in cones group | |

| Interventions | 1. PFMT (n = 30): initial training plus 1 30‐min visit/week. 10 fast and 10 slow 10‐s contractions for 2 periods of 15 min daily 2. Cones (n = 30): initial training, plus holding cones for 15 min twice daily. Femina cones, 5 conical weights, 20‐70 g | |

| Outcomes | Urinary diaries (leakages/week) Pad use VAS of severity and psychological distress | |

| Notes | Dropouts: after the first visit 14/30 women in the cones group withdrew, so did not receive the treatment. None of the electrostimulation group withdrew. All participants are in the analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "A list of random numbers were generated using a computer." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "A numbered opaque sealed envelope containing the method indicator card was opened by the secretary of the department." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patient reported outcomes | High risk | Not possible to blind participants, but possibly influenced by almost half of women in the cones group stopping treatment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Assessor measured outcomes | Unclear risk | No mention of blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All who were randomised were in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Does not appear to have any unreported outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | No reason to suspect other biases |

Castro 2008.

| Methods | 4‐armed parallel RCT. Method of group allocation not stated. The sole outcome assessor was blinded for outcomes that could be blinded. Treatment was for 6 months with outcomes measured at the end of treatment | |