Abstract

Background

It is possible that oestrogen deficiency may be an aetiological factor in the development of urinary incontinence in women. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2003 and subsequently updated in 2009.

Objectives

To assess the effects of local and systemic oestrogens used for the treatment of urinary incontinence.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register of trials (searched 21 June 2012) which includes searches of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings, and the reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials that included oestrogens in at least one arm in women with symptomatic or urodynamic diagnoses of stress, urgency or mixed urinary incontinence or other urinary symptoms post‐menopause.

Data collection and analysis

Trials were evaluated for risk of bias and appropriateness for inclusion by the review authors. Data were extracted by at least two authors and cross checked. Subgroup analyses were performed by grouping participants under local or systemic administration. Where appropriate, meta‐analysis was undertaken.

Main results

Thirty‐four trials were identified which included approximately 19,676 incontinent women of whom 9599 received oestrogen therapy (1464 involved in trials of local vaginal oestrogen administration). Sample sizes of the studies ranged from 16 to 16,117 women. The trials used varying combinations of type of oestrogen, dose, duration of treatment and length of follow up. Outcome data were not reported consistently and were available for only a minority of outcomes.

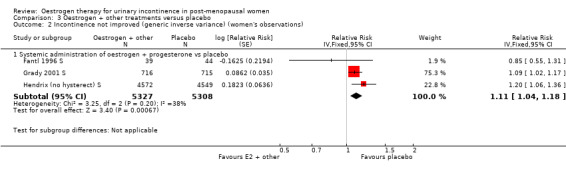

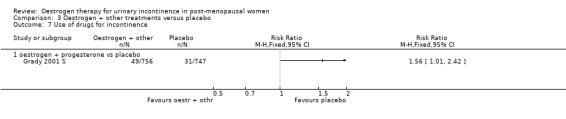

The combined result of six trials of systemic administration (of oral systemic oestrogens) resulted in worse incontinence than on placebo (risk ratio (RR) 1.32, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48). This result was heavily weighted by a subgroup of women from the Hendrix trial, which had large numbers of participants and a longer follow up of one year. All of the women had had a hysterectomy and the treatment used was conjugated equine oestrogen. The result for women with an intact uterus where oestrogen and progestogen were combined also showed a statistically significant worsening of incontinence (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.18).

There was some evidence that oestrogens used locally (for example vaginal creams or pessaries) may improve incontinence (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.86). Overall, there were around one to two fewer voids in 24 hours amongst women treated with local oestrogen, and there was less frequency and urgency. No serious adverse events were reported although some women experienced vaginal spotting, breast tenderness or nausea.

Women who were continent and received systemic oestrogen replacement, with or without progestogens, for reasons other than urinary incontinence were more likely to report the development of new urinary incontinence in one large study.

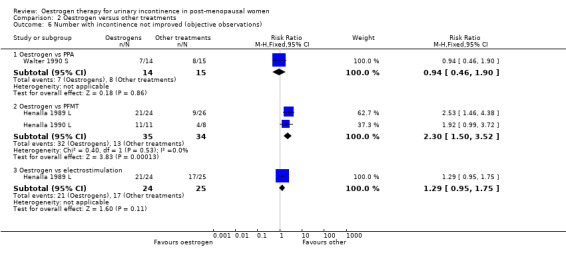

One small trial showed that women were more likely to have an improvement in incontinence after pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) than with local oestrogen therapy (RR 2.30, 95% CI 1.50 to 3.52).

The data were too few to address questions about oestrogens compared with or in combination with other treatments, different types of oestrogen or different modes of delivery.

Authors' conclusions

Urinary incontinence may be improved with the use of local oestrogen treatment. However, there was little evidence from the trials on the period after oestrogen treatment had finished and no information about the long‐term effects of this therapy was given. Conversely, systemic hormone replacement therapy using conjugated equine oestrogen may worsen incontinence. There were too few data to reliably address other aspects of oestrogen therapy, such as oestrogen type and dose, and no direct evidence comparing routes of administration. The risk of endometrial and breast cancer after long‐term use of systemic oestrogen suggests that treatment should be for limited periods, especially in those women with an intact uterus.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Postmenopause; Estrogen Replacement Therapy; Estrogen Replacement Therapy/adverse effects; Estrogens; Estrogens/adverse effects; Estrogens/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Urinary Incontinence; Urinary Incontinence/chemically induced; Urinary Incontinence/drug therapy; Urinary Incontinence, Stress; Urinary Incontinence, Stress/chemically induced; Urinary Incontinence, Stress/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Oestrogens for urinary incontinence in women

Urinary incontinence is the leakage of urine when coughing or exercising (stress urinary incontinence) or after a strong uncontrollable urge to urinate (urgency urinary incontinence). In women who have gone through the menopause, low oestrogen levels may contribute to urinary incontinence. The review found 34 trials including more than 19,000 women of whom over 9000 received oestrogen. The review found that significantly more women who received local (vaginal) oestrogen for incontinence reported that their symptoms improved compared to placebo. There was no evidence about whether the benefits of local oestrogen continue after stopping treatment but this seems unlikely as women would revert to having naturally low oestrogen levels. Trials investigating systemic (oral) administration, on the other hand, found that women reported worsening of their urinary symptoms. The evidence comes mainly from two very large trials including 17,642 incontinent women. These trials were investigating other effects of hormone replacement therapy as well as incontinence, such as prevention of heart attacks in women with coronary heart disease, bone fractures, breast and colorectal cancer. In addition, in one large trial women who did not have incontinence at first were more likely to develop incontinence. There may be risks from long‐term use of systemic oestrogen, such as heart disease, stroke and cancer of the breast and uterus.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oestrogen compared to placebo or no treatment for urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women.

| Oestrogen compared to placebo or no treatment for urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women Settings: Intervention: Oestrogen Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or no treatment | Oestrogen | |||||

| Incontinence not improved (generic inverse variance) (women's observations) ‐ Systemic administration (any incontinence) | 640 per 1000 | 845 per 1000 (749 to 948) | RR 1.32 (1.17 to 1.48) | 6151 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Incontinence not improved (generic inverse variance) (women's observations) ‐ Local administration (any incontinence) | 888 per 1000 | 657 per 1000 (568 to 764) | RR 0.74 (0.64 to 0.86) | 213 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| Incontinent episodes over 24 hours ‐ Systemic administration | The mean incontinent episodes over 24 hours ‐ systemic administration in the intervention groups was 0.54 higher (0.5 lower to 1.57 higher) | 82 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |||

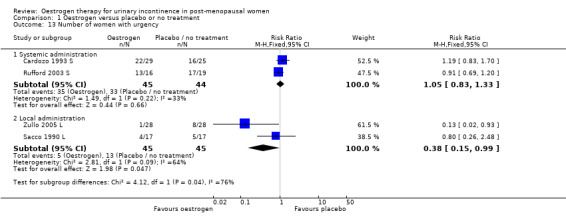

| Number of women with urgency ‐ Systemic administration | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.83 to 1.33) | 89 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 750 per 1000 | 788 per 1000 (622 to 998) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 767 per 1000 | 805 per 1000 (637 to 1000) | |||||

| Number of women with urgency ‐ Local administration | Study population | RR 0.38 (0.15 to 0.99) | 90 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | ||

| 289 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (43 to 286) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 290 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (44 to 287) | |||||

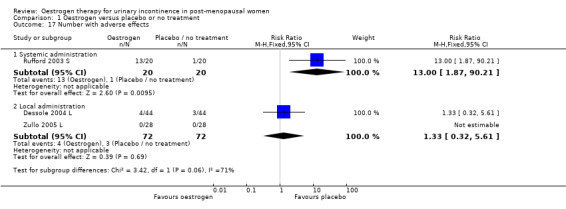

| Number with adverse effects ‐ Systemic administration | Study population | RR 13 (1.87 to 90.21) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 650 per 1000 (94 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 650 per 1000 (94 to 1000) | |||||

| Number with adverse effects ‐ Local administration | Study population | RR 1.33 (0.32 to 5.61) | 144 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate7 | ||

| 42 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (13 to 234) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 34 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (11 to 191) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Overall pooled effect is driven by one very large study (Hendrix) 2 High risk of bias in Henalla trial 3 P value for heterogeneity is <0.0003; I2 = 84% 4 P = 0.22 for heterogeneity (women with urgency ‐ systemic) 5 P = 0.09 for heterogeneity , I2 = 64% (women with urgency ‐ local) 6 Wide CI for Rufford trial (adverse effects for systemic) 7 Wide CI for pooled estimate (adverse effects of local)

Summary of findings 2. Oestrogen versus other treatments for urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women.

| Oestrogen versus other treatments for urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women Settings: Intervention: Oestrogen versus other treatments | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oestrogen versus other treatments | |||||

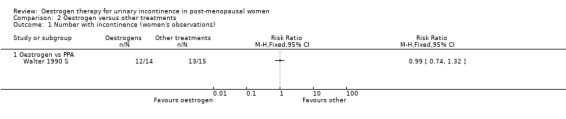

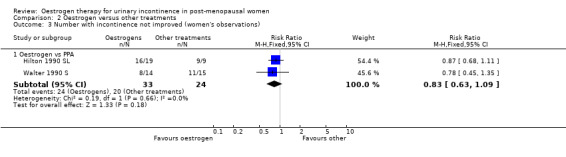

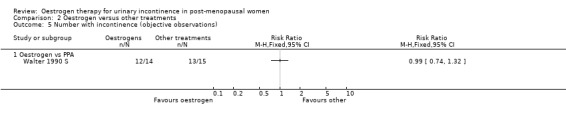

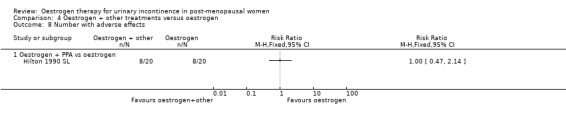

| Number with incontinence not improved (women's observations) ‐ Oestrogen vs PPA | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.63 to 1.09) | 57 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 833 per 1000 | 692 per 1000 (525 to 908) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 867 per 1000 | 720 per 1000 (546 to 945) | |||||

| Adverse effects ‐ oestrogen vs PPA | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Relative risk reduction greater than 25% in pooled estimate 2 One trial (Hilton) measured outcome, confidence interval crosses line of no effect

Summary of findings 3. Oestrogen + other treatments versus placebo for urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women.

| Oestrogen + other treatments versus placebo for urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with urinary incontinence in post‐menopausal women Settings: Intervention: Oestrogen + other treatments versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oestrogen + other treatments versus placebo | |||||

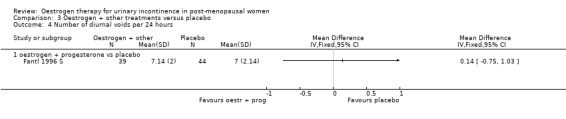

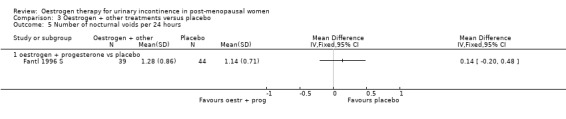

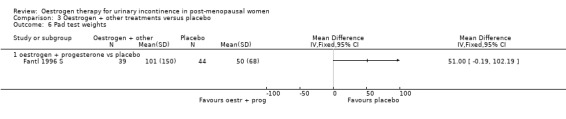

| Incontinent episodes over 24 hours ‐ oestrogen + progesterone vs placebo | The mean incontinent episodes over 24 hours ‐ oestrogen + progesterone vs placebo in the intervention groups was 0.43 lower (1.17 lower to 0.31 higher) | 83 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |||

| Incontinence not improved (generic inverse variance) (women's observation) ‐ oestrogen + other treatments versus placebo | 663 per 1000 | 736 per 1000 (689 to 782) | RR 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) | 10,635 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Number with incontinence not improved (women's observations) ‐ oestrogen + progesterone vs placebo (Copy) | Study population | RR 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16) | 1514 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 663 per 1000 | 716 per 1000 (669 to 769) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 608 per 1000 | 657 per 1000 (614 to 705) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Confidence interval crosses line of no effect (‐0.20, 0.48) 2 Confidence interval of Fantl trial crosses line of no effect

Background

There are three major naturally occurring oestrogens in women (oestradiol, oestriol, oestrone). It is possible that oestrogen deficiency, for example after the menopause, may be an aetiological factor in the development of urinary incontinence in women. However, it is not known whether oestrogen replacement will help in the treatment of this condition.

Description of the condition

Urinary incontinence is a common and embarrassing problem which may affect women of all ages. Although not life threatening, incontinence can lead to loss of confidence and in some cases social isolation. Urinary incontinence is the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine (Haylen 2010). Although treatment may be started based on symptoms alone, investigations may be used to accurately diagnose the underlying cause of the incontinence. The value of urodynamics in the management of urinary incontinence has yet to be established (Glazener 2012).

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI), which is the symptom of involuntary loss of urine associated with coughing, sneezing or physical activity, is the most common type (Haylen 2010). Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is the involuntary loss of urine accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency, which is a sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer. Overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome is diagnosed when women have urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without UUI, and in the absence of other pathology such as urinary tract infection (UTI) (Haylen 2010). These symptoms may also occur when the bladder is overactive, known as detrusor overactivity (DO), when it is diagnosed using urodynamics. Urodynamic stress incontinence (USI) is diagnosed when stress incontinence is confirmed in the absence of DO, using urodynamic studies. However, many women have a combination of problems including urinary frequency, urgency, and urgency urinary incontinence. Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) is diagnosed when SUI and UUI, or SUI and DO, co‐exist.

Early studies of oestrogen therapy for incontinence were performed before the widespread use of urodynamic investigation. Therefore, it is likely that those earlier studies included a heterogeneous group of women, some of whom may have had a number of different types of urinary symptoms such as overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) or voiding difficulties (VD) in addition to incontinence.

Description of the intervention

Oestrogen can be given to post‐menopausal women to prevent osteoporosis as well as treat symptoms of menopause, such as hot flushes, vaginal dryness, fatigue, irritability, sweating and incontinence. Synthetic oestrogen can be given using a variety of different doses, routes and modes of delivery or formulations (oral or vaginal tablet, cream, skin patch, subcutaneous implant). Routes include systemic, such as oral and transdermal; or local, including vaginal and into the bladder (intravesical). Duration of therapy and assessment of effect also vary widely. The situation may be confounded by the concurrent use of progestogens to prevent endometrial hyperplasia in women who have not had a hysterectomy, which may themselves exacerbate both irritative urinary symptoms and incontinence (Benness 1991).

How the intervention might work

The female genital and urinary tracts both arise from the primitive urogenital sinus and develop in close anatomical proximity. Oestrogen receptors have been identified in the tissues of the vagina, bladder, urethra and muscles of the pelvic floor (Blakeman 1996; Iosif 1981; Smith 1993). Sex hormones such as oestrogen have a substantial influence on the female bladder throughout adult life with fluctuations in their levels leading to macroscopic, histological and functional changes. Urinary symptoms may therefore develop during the menstrual cycle, in pregnancy and following the menopause (Barlow 1997; Cutner 1992; Van Geelen 1981).

As the tissues involved in the female continence mechanism are oestrogen sensitive, it is possible that oestrogen deficiency may be an aetiological factor in the development of urinary incontinence. Epidemiological surveys have shown that the peak prevalence of stress incontinence occurs around the time of the natural menopause (Jolleys 1988; Kondo 1990; Thomas 1980). In addition, 70% of incontinent post‐menopausal women have been reported to relate the onset of their incontinence to the time of their final menstrual period (Iosif 1984). On the other hand, many studies show that more pre‐menopausal women are affected by incontinence than post‐menopausal women, with the prevalence of stress incontinence actually falling following the menopause (Hannestad 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

A variety of other options are available for the treatment of incontinence, including pelvic floor muscle training (Dumoulin 2010; Boyle 2012; Herbison 2002; Kovoor 2008; Patel 2008), vaginal ring pessaries (Lipp 2011), a number of different types of medication (Alhasso 2005; Madhuvrata 2012; Nabi 2006; Roxburgh 2007) and surgery (Dean 2006; Glazener 2001; Glazener 2004; Kirchin 2012; Lapitan 2012; Liapis 2010 L; Ogah 2009; Rehman 2011). The female hormone oestrogen has been used to treat incontinence over a number of years, either alone or in combination with some of these other options. However, most trials involve only a small number of women and few have attempted long‐term follow up. Two very large trials of women receiving hormone replacement therapy have been published showing a negative effect of hormones on incontinence (Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S). This review will consider all of the evidence regarding oestrogen therapy as a treatment for incontinence.

Objectives

To assess the effects (both beneficial and harmful) of oestrogen therapy used for the treatment of urinary incontinence.

The following comparisons were made.

1. Oestrogen therapy versus placebo or no treatment for urinary incontinence.

2. Oestrogen therapy versus other forms of treatment (e.g. physical, drugs, surgery) for urinary incontinence.

3. Oestrogen combined with other therapy versus placebo or no treatment for urinary incontinence.

4. Oestrogen given in combination with another treatment versus oestrogen given alone for urinary incontinence.

5. Oestrogen given in combination with another treatment versus that other treatment given alone for urinary incontinence.

6. One type of oestrogen versus another.

7. One method of administration of oestrogen versus another.

8. A high dose of oestrogen versus a lower dose. Subgroup analysis was performed according to the route of administration (systemic or local).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials of oestrogen therapy for the treatment of urinary stress, urgency or mixed incontinence.

Types of participants

Post‐menopausal women with urinary incontinence and diagnosed as having urinary stress, urgency or mixed incontinence either by symptom classification or by urodynamic diagnosis, as defined by the trialists.

Types of interventions

a) Oestrogen therapy, which includes different types of oestrogens, different doses and different routes of administration.

b) Comparators: no therapy, placebo, or non‐oestrogen therapies (which include physical, pessary, drugs and surgery).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Women's observations

Continuing incontinence or lack of improvement in incontinence

Secondary outcomes

2. Quantification of symptoms

Pad changes over 24 hours (self‐reported number of pads used)

Incontinent episodes per 24 hours (as indicated from self‐completed bladder chart)

Frequency (micturitions per 24 hours)

Pad tests of quantified leakage (weight of urine loss)

Urgency

3. Clinician's measures (urodynamics or cystometry)

Maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP) (cm H²O)

Volume at first urge to void (ml)

Maximum bladder capacity (ml)

4. Quality of life

Severity of incontinence e.g. index score: slight, moderate or severe (Sandvik 1993)

Impact of incontinence on quality of life e.g. Urogenital distress Inventory (Shumaker 1994), Disease Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (Jackson 1996; Kelleher 1997)

Psychological measures e.g. Crown‐Crisp Experimental Index (Crown 1979)

General health status e.g. Short Form‐36 (Ware 1993)

5. Socioeconomics

Costs of intervention(s)

Resource implications of differences in outcomes

Formal economic analysis (cost effectiveness, cost utility)

6. Adverse outcomes

Vaginal bleeding

Uterine cancer

Cardiovascular disease e.g. stroke, heart disease

Breast cancer

7. Other outcomes

Non‐prespecified outcomes that were judged important when performing the review

Search methods for identification of studies

Limitations such as different languages were not imposed on any of the searches described below.

Electronic searches

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed for the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register of controlled trials, which is described under the Incontinence Group's module in The Cochrane Library. The register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, CINAHL and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. The date of the most recent search of the register for this review was 21 June 2012.

The trials in the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The terms used to search the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are given below: ({DESIGN.CCT*} OR {DESIGN.RCT*}) AND ({INTVENT.CHEM.HORM*} OR {INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.ESTROGEN CREAM.} OR {INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.MESTINON.} OR {INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.MISOPROSTOL} OR {INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.NORETHANDROLONE} OR {INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.TAMOXIFEN.}) (all searches were of the keywords field of Reference Manager 12, Thomson Reuters).

Searching other resources

The review authors also searched the reference lists of relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Trials under consideration were evaluated for risk of bias and appropriateness for inclusion by at least two review authors, without prior consideration of the results. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or with a third party. Assessment of risk of bias was undertaken by at least two authors using the Cochrane Collaboration's assessment criteria, which include quality of random allocation concealment, description of dropouts and withdrawals, analysis on an intent to treat, and 'blinding' at treatment and outcome assessment. Again, any disagreements were resolved by discussion or with a third party.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was undertaken independently by all three review authors. Where data may have been collected in a study but was not reported, further clarification was sought from the trialists. Trial data were analysed according to the treatment or type of intervention compared and grouped, if possible, by route of administration (systemic or local). Any differences of opinion related to the data extracted were resolved by discussion or with a third party.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Studies were excluded if they were not randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials, or if they made comparisons other than those specified for the review. These studies are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Measures of treatment effect

Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When appropriate, meta‐analysis was undertaken of the parallel group studies. For categorical outcomes the numbers in each group reporting an outcome were related to the numbers at risk to derive a risk ratio (RR), where sufficient data to calculate an RR were available. The data were combined using the Mantel‐Haenszel method. For continuous variables we used means and standard deviations to derive a mean difference (MD). When summary data were not available from all trials for a particular outcome and only adjusted risk ratios were reported, the generic inverse variance method was used to combine risk ratios. A fixed‐effect model was used for calculation of pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data from these trials were presented in 'Other data' tables only.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Trials were only combined if the interventions were similar enough based on clinical criteria (types of interventions). Differences between trials were investigated if significant heterogeneity was found at the statistical significance level of 10% or by using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003), or it appeared obvious from visual inspection of the results. If there was no obvious reason for the heterogeneity, use of a random‐effects model was considered. If a reason was found then a judgement was made as to whether it was reasonable to combine the results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Trial data were grouped by route of administration (systemic or local), where possible. The suffix S or L was used to denote systemic or local administration, respectively. Further details on type of oestrogen, dose, length of treatment and population (type of urinary incontinence, menopausal status) are given in Table 4.

1. Summary of study characteristics: type of oestrogen, route of administration, dose, length of treatment, population.

| Study ID | Type of Oestrogen | Route of administration | Dose | Length of treatment | Population | |

| Ahlstrom 1990 S | Oestriol | Systemic (oral) | 4mg | 6 weeks | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Assassa 2003 L | Oestrogen | Local (vaginal ring) | ? | 3 months | UI, postmenopausal | |

| Beisland 1984 L | Oestriol | Local (vaginal) | 1 mg | 8 weeks | UI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Blom 1995 S | Estradiol | Systemic (transdermal) | 0.05 mg | 8 weeks | UUI (OAB), elderly | |

| Cardozo 1993 S | Oestriol | Systemic (oral) | 3 mg | 3 months | UUI (urge), postmenopausal | |

| Cardozo 2001 L | Oestradiol | Vaginal (pessary, Vagifem) | 25 µgm | 3 months | OAB (urge), postmenopausal | |

| Dessole 2004 L | Oestriol | Local (intravaginal ovules) | 1‐2 mg | 6 months | UI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Ek 1980 S | Oestradiol | Systemic (oral) | 1 mg | 6 weeks | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Enzelsberger 1990 L | Oestriol | Local (vaginal) | 0.5, 1 or 2 mg | Not stated | UI (urge), OAB | |

| Enzelsberger 1991a L; Enzelsberger 1991b L | Oestriol | Local (vaginal) | 1 mg or 3 mg | 3 weeks | UI (urge), OAB, postmenopausal | |

| Fantl 1996 S | Conjugated equine oestrogens + medroxyprogesterone | Systemic (oral) | 0.625 mg / 10 mg | 3 months | UI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Grady 2001 S | Conjugated oestrogens (premarin) + medroxyprogesterone | Systemic (oral) | 0.625 mg / 2.5 mg | up to 4 years | UI (unspecified), postmenopausal, heart disease, age <80 years, with uterus | |

| Henalla 1989 L | Conjugated equine oestrogen | Local (vaginal cream) | 1.25 mg | 3 months | USI (stress) | |

| Henalla 1990 L | Conjugated equine oestrogen | Local (vaginal cream) | 2 gm | 6 weeks | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Hendrix (hysterectomy) S | Conjugated equine oestrogen | Systemic (oral) | 0.625 mg | 1 year | UI (SUI, UUI, MUI), postmenopausal, prevention of heart disease and hip fracture Without uterus |

|

| Hendrix (no hysterect) S | Conjugated equine oestrogen + medroxyprogesterone | Systemic (oral) | 0.625 mg / 2.5 mg | 1 year | UI (SUI, UUI, MUI), postmenopausal, prevention of heart disease and hip fracture With uterus |

|

| Hilton 1990 SL | Oestrogen | Local (intravaginal) Systemic (oral) |

2 gm 1.25 mg |

1 month | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Ishiko 2001 S | Estriol | Systemic (oral) | 1 mg | 2 years | SUI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Jackson 1999 S | Oestradiol | Systemic (oral) | 2 mg | 6 months | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Judge 1969 S | Quinestradiol | Not stated | 1 mg | 1 month | UI (unspecified), postmenopausal, geriatric inpatients | |

| Kinn 1988 S | Oestriol | Systemic (oral) | 4 mg | 1 month | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Kurz 1993 L | Oestriol | Local (intravesical) | 1 mg | 3 weeks | UUI, OAB (urge), postmenopausal | |

| Liapis 2010 L | Oestradiol | Local (intravaginal tablets) | 25 mcg | 6 months | SUI | |

| Lose 2000 L | Oestradiol | Local (intravaginal ring, vaginal pessaries) | ring 7.5mg, pessary 0.5 mg | 6 months | UI (unspecified), LUT symptoms, postmenopausal | |

| Melis 1997 L | Oestriol | Local (intravaginal) | 0.5 mg | 3 months | UI, menopausal symptoms | |

| Ouslander 2001 S | Oestrogen + progesterone | Systemic (oral) | 0.625 mg / 2.5 mg | 6 months | UI (unspecified), nursing home residents | |

| Rufford 2003 S | 17‐beta oestradiol | Systemic (implant) | 25 mg | 6 months | UUI, OAB (urge), postmenopausal | |

| Sacco 1990 L | Oestrogen | Local (cream) | 0.5 mg | 3 months | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Samsioe 1985 S | Oestriol | Systemic (oral) | 3 mg | 3 months | MUI (mixture), postmenopausal | |

| Tinelli 2007 L | Oestradiol | Systemic (oral) | 10 mg | 12 months | SUI | |

| Tseng 2007 L | Oestrogen | Local (vaginal) | 1 gm | 12 weeks | OAB | |

| Walter 1978 S | Oestradiol + oestriol | Systemic (oral) | 2 mg / 1 mg | 4 months (with breaks) | SUI, MUI (stress and mixed), postmenopausal | |

| Walter 1990 S | Oestriol | Systemic (oral) | 4 mg | 1‐2 months | SUI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Wilson 1987 S | Piperazine oestrone sulphate | Systemic (oral) | 3 mg | 3 months (with breaks) | USI (stress), postmenopausal | |

| Zullo 2005 L | Estriol | Local (intravaginal ovules) | 1 mg | 6 months | SUI (stress), postmenopausal |

LUTs = lower urinary tract symptoms; MUI = mixed urinary incontinence; OAB = overactive bladder syndrome; SUI = stress urinary incontinence; UI = urinary incontinence; USI = urodynamic stress incontinence; UUI = urgency urinary incontinence.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

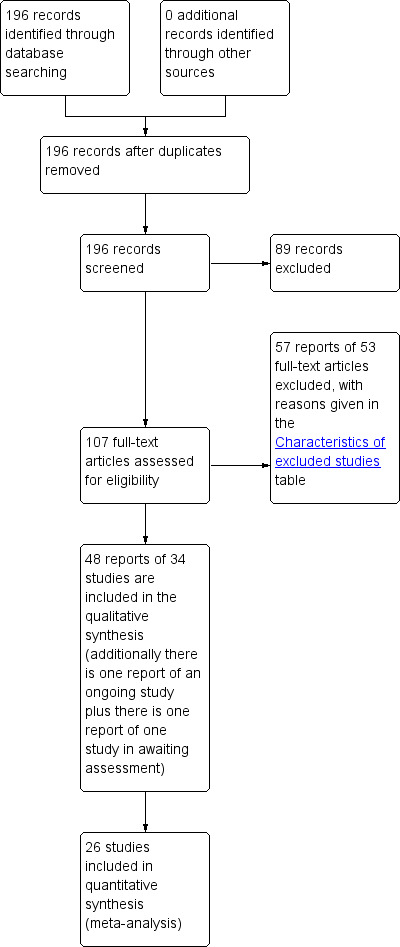

The literature search generated 196 records to assess. A total of 87 studies were considered for this review, of which 53 were excluded for the reasons listed in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. In the first update of the original Cochrane review (Moehrer 2003), an extra six trials were included (Dessole 2004 L; Hendrix 2005 S; Ishiko 2001 S; Tinelli 2007 L; Tseng 2007 L; Zullo 2005 L), three trials were updated with new information (Cardozo 2001 L; Grady 2001 S; Rufford 2003 S) and an extra 10 studies were excluded. Two previously included trials were excluded because some of the women were continent (Rud 1980; Chompootaweep 1998 SL). In total, 34 RCTs are now included (see Characteristics of included studies). One study is ongoing (Sant 2002) and one study is 'Awaiting assessment' (Bergman 1985) as the study methods are unclear. The flow of records through the assessment process can be seen in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Included studies

Of the 34 included trials, 18 investigated systemic administration and 17 trials investigated local administration. One trial investigated both local and systemic administration (Hilton 1990 SL). Thirty‐two were full reports and two were published as abstracts only. Three trials were published in German, one in Italian and one in Polish. The remainder of the trials were published in English. Seven trials used a crossover design (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Beisland 1984 L; Blom 1995 S; Ek 1980 S; Judge 1969 S; Kinn 1988 S; Samsioe 1985 S).

Twenty‐six trials had two trial arms, four trials had three trial arms, one trial had four trial arms, and one trial had six trial arms.

The duration of the treatments in the trials also differed: one trial was done over three weeks, five over four weeks, one over five weeks, two over eight weeks, nine over three months, one over four months, nine over six months, one over seven months, two over 12 months, and one over four years (Grady 2001 S). A summary of the types of oestrogens, route of administration, dose of oestrogen, duration of treatment and type of population is given in Table 4.

Sample characteristics

The trials included a total of 19,676 women who had urinary incontinence, of which approximately 9599 received oestrogen therapy (1464 were involved in trials of local oestrogen administration). The sample sizes for each trial ranged from 16 to 16,117 participants. Two large trials were of women receiving systemic hormone replacement therapy for reasons other than incontinence (control of coronary heart disease: Grady 2001 S, N = 1525; prevention of coronary heart disease and hip fracture: Hendrix 2005 S, N = 16,117 incontinent women). Every trial used different inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Type of incontinence

Trials were undertaken on women with urge, stress, mixed or non‐specified incontinence. A range of urodynamic or symptomatic measures were used in the different trials to confirm incontinence. Women were recruited on the basis of symptoms of incontinence or urodynamic diagnosis:

17 trials selected women with stress urinary incontinence (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Beisland 1984 L; Dessole 2004 L; Ek 1980 S; Fantl 1996 S; Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Ishiko 2001 S; Jackson 1999 S; Kinn 1988 S; Liapis 2010 L; Sacco 1990 L; Tinelli 2007 L; Walter 1990 S; Wilson 1987 S; Zullo 2005 L);

eight included women with urgency urinary incontinence (Blom 1995 S; Cardozo 1993 S; Cardozo 2001 L; Enzelsberger 1990 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Kurz 1993 L; Rufford 2003 S; Tseng 2007 L);

five trials involved a mixed population of women with different types of incontinence or women with mixed incontinence (Assassa 2003 L; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Samsioe 1985 S; Walter 1978 S);

two trials selected women with urogenital symptoms including incontinence (Lose 2000 L; Melis 1997 L); and

two trials were in elderly women with incontinence and who lived in nursing homes (Judge 1969 S; Ouslander 2001 S).

Menopausal status

All trials examined post‐menopausal women. Most trials excluded women who had used hormone or oestrogen replacement therapy in the preceding two to 12 months, who suffered from a urinary or urogenital infection, or who had contraindications to oestrogen therapy such as oestrogen dependent malignancy, thromboembolic disorders or severe liver disease. Often women with diabetes mellitus or neurological disease were excluded. A major prolapse was an exclusion criterion in some trials, as were symptoms that had started more than three years before the menopause.

Route of administration

Systemic (18 trials)

Oral tablets (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Cardozo 1993 S; Ek 1980 S; Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Hilton 1990 SL; Ishiko 2001 S; Jackson 1999 S; Judge 1969 S; Kinn 1988 S; Ouslander 2001 S; Samsioe 1985 S; Walter 1978 S; Walter 1990 S; Wilson 1987 S)

Transdermal patches (Blom 1995 S)

Subcutaneous implant (Rufford 2003 S)

Local (17 trials)

Vaginal pessaries or tablets (Cardozo 2001 L; Dessole 2004 L; Liapis 2010 L; Lose 2000 L; Zullo 2005 L)

Vaginal cream (Beisland 1984 L; Enzelsberger 1990 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Melis 1997 L; Sacco 1990 L; Tinelli 2007 L; Tseng 2007 L)

Oestradiol‐releasing vaginal ring (Assassa 2003 L; Lose 2000 L)

Intravesical (into the bladder) (Kurz 1993 L)

Type of oestrogen

1. Oestrogen versus placebo

Systemic

Oestradiol (Blom 1995 S; Jackson 1999 S; Rufford 2003 S)

Oestriol (Cardozo 1993 S; Samsioe 1985 S)

Combination of 2 mg oestradiol and 1 mg oestriol tablets (Walter 1978 S)

Conjugated equine oestrogen (Hendrix 2005 S)

Piperazine oestrone sulfate tablets (Wilson 1987 S)

Quinestradiol (Judge 1969 S)

Local

Oestradiol (Assassa 2003 L; Cardozo 2001 L)

Oestriol (Dessole 2004 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Kurz 1993 L; Zullo 2005 L)

Conjugated equine oestrogen (Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Sacco 1990 L)

2. Oestrogen versus other treatments

Systemic

Two trials compared oestrogens (oestradiol or oestriol) with phenylpropanolamine (PPA) (Hilton 1990 SL; Walter 1990 S)

Local

Two trials compared oestrogens (oestradiol or oestriol) with phenylpropanolamine (PPA) (Beisland 1984 L; Hilton 1990 SL)

Two trials compared oestrogen (conjugated equine oestrogen cream) with pelvic floor muscle training or electrostimulation (Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L)

3. Oestrogen plus other treatment versus placebo

Systemic

All four trials comparing oestrogen plus other treatment with placebo used a progestogen (medroxyprogesterone) in combination with conjugated equine oestrogens (Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Ouslander 2001 S)

4. Oestrogen plus other treatment versus oestrogen

Five trials compared oestrogen plus other treatment with oestrogen alone. The oestrogens were as follows.

Systemic

Oestriol (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Kinn 1988 S)

Oestradiol (Blom 1995 S; Ek 1980 S)

Conjugated equine oestrogen cream (Hilton 1990 SL)

Local

Oestriol (Melis 1997 L)

Conjugated equine oestrogen cream (Hilton 1990 SL)

The other treatment was:

an alpha‐adrenergic drug (phenylpropanolamine (PPA)) (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Ek 1980 S; Hilton 1990 SL; Kinn 1988 );

an anti‐inflammatory and antibacterial drug (benzidamine) (Melis 1997 L);

a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (naproxen) (Blom 1995 S).

5. Oestrogen plus other treatment versus other treatment

One trial compared oestrogen (conjugated equine oestrogen cream) plus PPA with PPA alone (Hilton 1990 SL). Another compared oestrogens plus pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) with PFMT alone (Ishiko 2001 S). Liapis et al (Liapis 2010 L) and Tinelli et al (Tinelli 2007 L) both compared oestrogen plus surgery versus surgery. Liapis et al compared vaginal oestrogen plus tension free vaginal tape‐obturator route (TVT‐O) versus TVT‐O in stress incontinent women. Tinelli et al (Tinelli 2007 L) also compared vaginal oestrogen plus tension free vaginal tape (TVT) versus TVT alone. TVT and TVT‐O are both minimally invasive surgical procedures for stress incontinence. Tseng (Tseng 2007 L) compared vaginal oestrogen plus detrusitol versus detrusitol for overactive bladder.

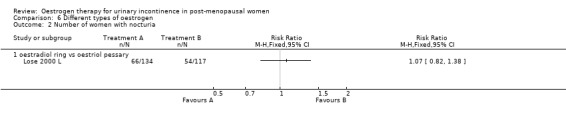

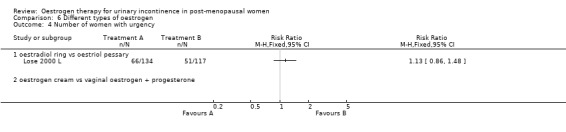

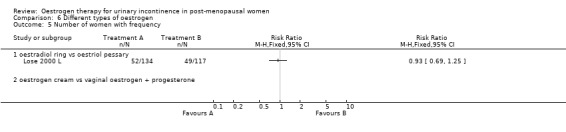

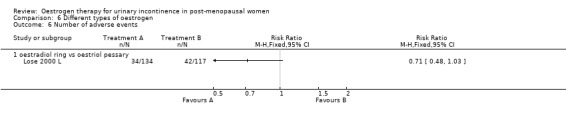

6. Different types of oestrogen

One trial directly compared different types of oestrogen. The comparisons were:

oestradiol‐releasing vaginal ring versus oestriol pessary (Lose 2000 L).

7. Different routes of administration

One trial directly compared different routes of administration:

vaginal conjugated equine oestrogen cream versus oral conjugated oestrogen (Hilton 1990 SL).

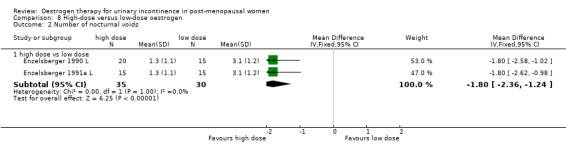

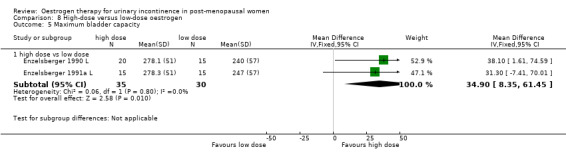

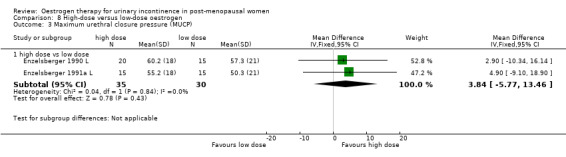

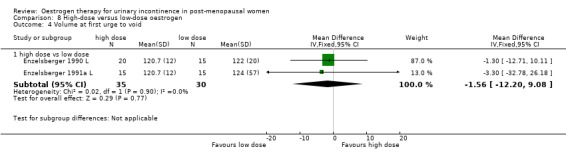

8. High‐dose versus low‐dose oestrogen

Two trials compared high‐dose with low‐dose oestrogen (oestriol) treatment administered locally (one trial is referenced twice for data entry purposes) (Enzelsberger 1990 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Enzelsberger 1991b L).

Outcome measures

The different studies used a variety of measures to assess subjective outcomes of treatment including visual analogue scales, a four‐point severity score scale, symptom questionnaires and simple questions. Objective outcomes such as frequency, urgency, nocturia, dysuria and number of incontinent episodes were mainly assessed by urinary diaries. Three trials reported quality of life measurements. Pad tests were performed in seven trials but all the tests were of a different type and duration. Fourteen trials reported urodynamic measurements but put their emphasis on different parameters. No trials reported economic outcome measures.

Duration of follow up

Three trials reported follow up after the trial treatment period (Henalla 1989 L; Kurz 1993 L; Wilson 1987 S). None of the other trials reported outcomes after the end of trial treatment. However, the effect of oestrogen treatment would not be expected to last after treatment stops as women would revert to their post‐menopausal oestrogen‐deficient status.

Excluded studies

Fifty‐three studies were excluded for reasons listed in the table Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

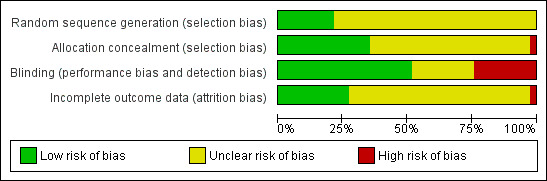

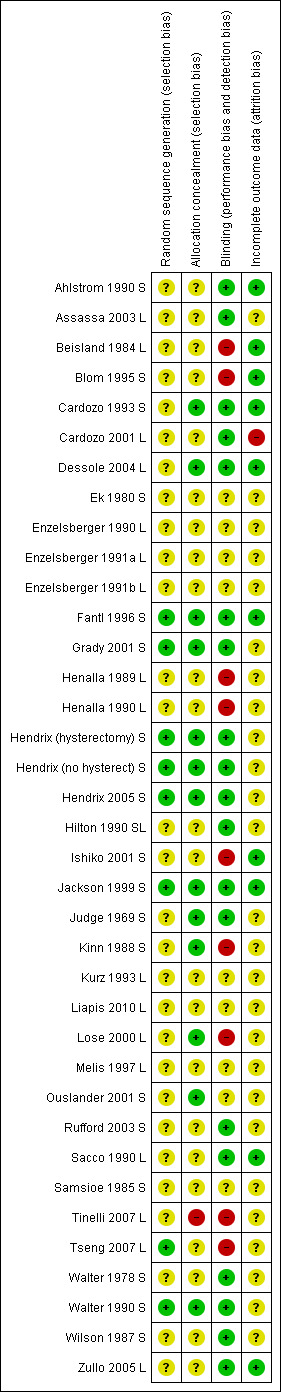

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

A total of 11 trials used an adequate method of allocation concealment (Cardozo 1993 S; Dessole 2004 L; Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Jackson 1999 S; Judge 1969 S; Kinn 1988 S; Lose 2000 L; Ouslander 2001 S; Walter 1990 S).

In 21 trials, the method of allocation concealment was unclear (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Assassa 2003 L: Beisland 1984 L; Blom 1995 S; Cardozo 2001 L; Ek 1980 S; Enzelsberger 1990 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Ishiko 2001 S; Kurz 1993 L; Liapis 2010 L; Melis 1997 L; Rufford 2003 S; Sacco 1990 L; Samsioe 1985 S; Walter 1978 S; Wilson 1987 S; Zullo 2005 L).

Blinding

Twenty trials were double‐blind (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Assassa 2003 L; Cardozo 1993 S; Cardozo 2001 L; Dessole 2004 L; Ek 1980 S; Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Hilton 1990 SL; Jackson 1999 S; Judge 1969 S; Kinn 1988 S; Kurz 1993 L; Ouslander 2001 S; Rufford 2003 S; Samsioe 1985 S; Walter 1978 S; Walter 1990 S; Wilson 1987 S). In one trial the women were blinded to their treatment but the assessors were not (Blom 1995 S). In 11 trials neither women nor the assessors were blinded throughout the treatment course. It was not clear whether blinding had not been achieved or whether it was not possible to carry out blinding (Beisland 1984 L; Enzelsberger 1990 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L; Ishiko 2001 S; Liapis 2010 L; Lose 2000 L; Melis 1997 L; Sacco 1990 L; Zullo 2005 L).

Incomplete outcome data

Dropsouts or losses to follow up were reported in 19 out of the 35 trials included in the review (Beisland 1984 L; Cardozo 1993 S; Cardozo 2001 L; Ek 1980 S; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Hilton 1990 SL; Ishiko 2001 S; Jackson 1999 S; Judge 1969 S; Liapis 2010 L; Lose 2000 L; Melis 1997 L; Ouslander 2001 S; Rufford 2003 S; Walter 1990 S; Wilson 1987 S). The trials reported between 2% to 10% losses to follow up at varying times.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Comparison 1. oestrogen therapy versus placebo or no treatment for urinary incontinence

The 20 trials that compared oestrogen with placebo (Hilton 1990 compared systemic and local), 10 systemic oestrogen (Blom 1995 S; Cardozo 1993 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Hilton 1990 SL; Jackson 1999 S; Judge 1969 S; Rufford 2003 S; Samsioe 1985 S; Walter 1978 S; Wilson 1987 S) and 10 local oestrogen (Assassa 2003 L; Cardozo 2001 L; Dessole 2004 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Kurz 1993 L; Sacco 1990 L; Zullo 2005 L), had varying combinations of types of oestrogen, doses, treatment durations and lengths of follow up. A variety of tests were used to measure subjective and objective outcomes. These were not consistent across the studies and so data for individual outcomes were usually available only for a minority of trials.

The three trials (Blom 1995 S; Judge 1969 S; Samsioe 1985 S) which used a crossover design provided no useable data for any of the outcomes in this comparison.

Women's observations

Number with incontinence

Systemic

The results of four small trials showed a statistically significant result favouring oestrogen (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98) (Analysis 1.1). However, the larger study (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S), demonstrating contradictory results, did not contribute data to this outcome. There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity and when a random‐effects model was used the result was no longer statistically significant (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.09). The combined data included studies of women with urgency (Cardozo 1993 S; Rufford 2003 S) and stress symptoms (Jackson 1999 S; Walter 1978 S). Different types of oestrogen were also used: oestriol (Cardozo 1993 S; Dessole 2004 L); oestradiol (Jackson 1999 S) and 17‐beta oestradiol (Walter 1978 S). The Hendrix trial (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S) used conjugated equine oestrogen.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Number with incontinence (women's observations).

Local

Three trials (Assassa 2003 L; Dessole 2004 L; Zullo 2005 L) compared local oestrogen against placebo. Two of the studies (Dessole 2004 L; Zullo 2005 L) favoured local administration (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.87) (Analysis 1.1) with the results being statistically significant, whilst the remaining study (Assassa 2003 L) reported no difference between patients in the two intervention groups. Statistical heterogeneity was shown in this meta analysis and when a random‐effects model was used the result was no longer statistically significant (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.03 to 5.29). The Zullo study included women after a TVT procedure and the main objective was to investigate the development of urgency. Assassa 2003 L included 220 post‐menopausal women. However, there were no data available in the paper to include in the analysis.

Number with incontinence not improved

Women not cured or improved were considered together.

Systemic

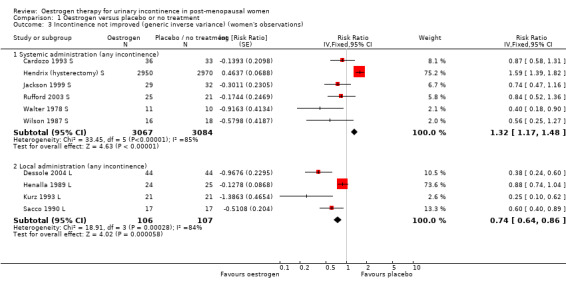

Data from a very large trial (Hendrix 2005 S), which aimed to investigate the effects of systemic hormone replacement treatment for prevention of coronary heart disease and bone fracture, included a subgroup analysis of women who had been incontinent at baseline (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S). When these data were combined (using generic inverse variance) with the results from five other small trials (Cardozo 1993 S; Jackson 1999 S; Rufford 2003 S; Walter 1990 S; Wilson 1987 S) the net effect was to suggest that systemic oestrogen treatment resulted in more urinary incontinence than placebo (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48) (Analysis 1.3). The statistical heterogeneity was high and the result was no longer statistically significant if a random‐effects model was used (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.28). Under this model the much larger Hendrix trial received less weight.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Incontinence not improved (generic inverse variance) (women's observations).

The women included from the Hendrix study in this meta analysis had all had a hysterectomy and the incontinence was measured at one year (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S). The Jackson and Rufford trials included women who had had a hysterectomy; the other trials made no mention of whether women had hysterectomies. Only Hendrix reported data separately. The result of this meta analysis was based mainly on the Hendrix trial, which received the highest weighting. This is related to the large number of participants (approximately 9000) who were involved. The RR of any urinary incontinence becoming worse was consistently higher in the group treated with oestrogen compared with placebo (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.39 to 1.82) (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S).

This effect was also seen for increased frequency of incontinence episodes (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.35 to 1.61) and for limitation of daily activities (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.45) as given in the trial report (data not shown) (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S).

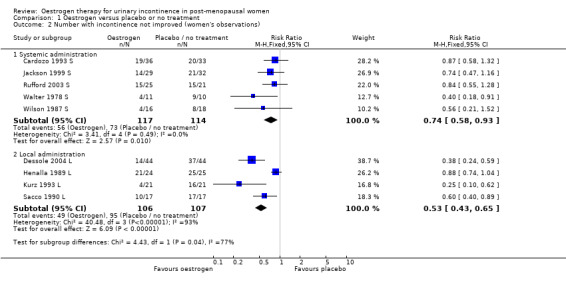

Local

Combination of data from the four small trials which used local oestrogen administration (Dessole 2004 L; Henalla 1989 L; Kurz 1993 L; Sacco 1990 L) demonstrated a benefit for oestrogen over placebo in terms of a reduction in incontinence (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.86) (Analysis 1.3). Statistical heterogeneity was demonstrated in this meta‐analysis. The Henalla study seemed to provide different results from the others with a CI which included favouring placebo, and this trial used conjugated equine oestrogen. Kurz used intravesical administration. Only the Kurz trial included women with urgency urinary incontinence; the other three trials were restricted to women with stress urinary incontinence. The result was still statistically significant when a more conservative random‐effects model was used (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.87).

Quantification of symptoms

Some data describing quantification of symptoms were available from 10 trials (Cardozo 1993 S; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Enzelsberger 1991b L; Henalla 1989 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Jackson 1999 S; Kurz 1993 L; Rufford 2003 S; Sacco 1990 L; Wilson 1987 S) although individual outcomes were not reported consistently.

Systemic

There were too few data to provide evidence of any effect for the outcomes on pad changes (Analysis 1.6), pad tests (Analysis 1.7), incontinent episodes (Analysis 1.8), number of voids in 24 hours (Analysis 1.9), number of nocturnal voids (Analysis 1.10) or number of women with frequency, nocturia or urgency.

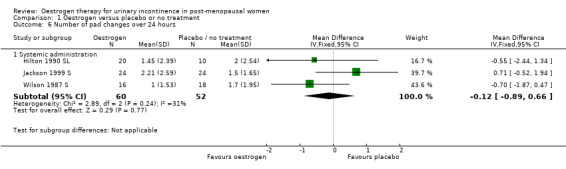

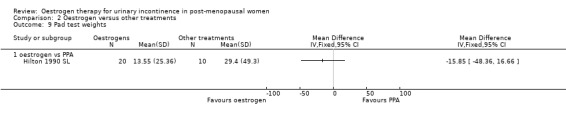

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6 Number of pad changes over 24 hours.

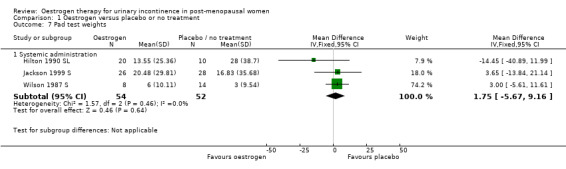

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 7 Pad test weights.

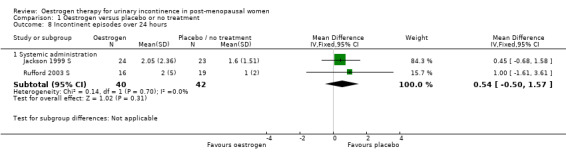

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 8 Incontinent episodes over 24 hours.

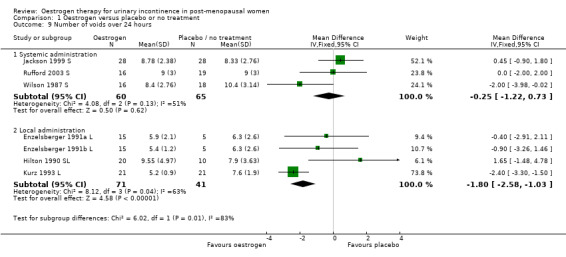

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 9 Number of voids over 24 hours.

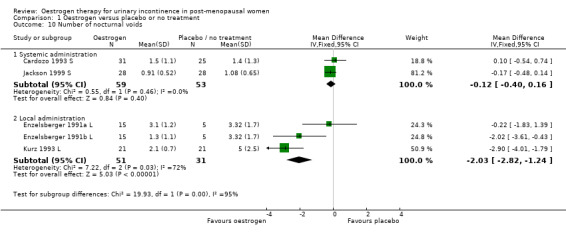

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 10 Number of nocturnal voids.

Local

There were few data describing objective improvements in terms of numbers of women observed to be incontinent (Analysis 1.4), pad changes or pad weights (Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7) or incontinent episodes (Analysis 1.8).

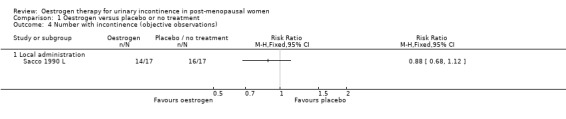

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Number with incontinence (objective observations).

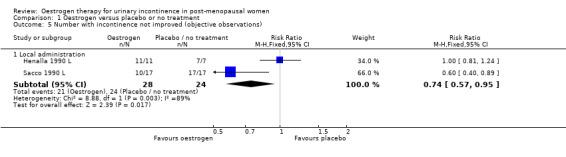

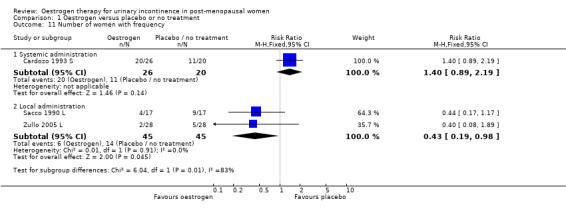

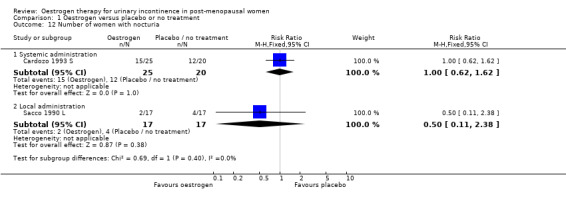

The results of two small trials (Henalla 1990 L; Sacco 1990 L) showed a statistically significant difference favouring local oestrogen in numbers of women whose incontinence had not improved (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.95) (Analysis 1.5.) There was evidence of a reduction in the number of voids in 24 hours (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐1.80, 95% CI ‐2.58 to ‐1.03) (Analysis 1.9) and nocturnal voids (WMD ‐2.03, 95% CI ‐2.82 to ‐1.24) (Analysis 1.10) with data favouring oestrogen. Although there was significant heterogeneity the result was still statistically significant when a random‐effects model was used. Overall, there were around one to two fewer voids in 24 hours and nocturnal voids amongst women treated with local oestrogen (Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10). The results from two studies (Sacco 1990 L; Zullo 2005 L) showed a statistically significant difference with respect to frequency (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.98) (Analysis 1.11) and urgency (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.99) (Analysis 1.13) favouring oestrogen. There were no statistically significant differences in nocturia (Analysis 1.12) but the CIs were wide reflecting the small size of the few trials with data.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 Number with incontinence not improved (objective observations).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 11 Number of women with frequency.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 13 Number of women with urgency.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 12 Number of women with nocturia.

Clinicians' measures

Data on urodynamic measurements (maximum urethral closure pressure, volume at first urge to void and maximum bladder capacity) were available for nine trials (Cardozo 1993 S; Enzelsberger 1991a L; Enzelsberger 1991b L; Henalla 1989 L; Jackson 1999 S; Kurz 1993 L; Rufford 2003 S; Sacco 1990 L; Wilson 1987 S).

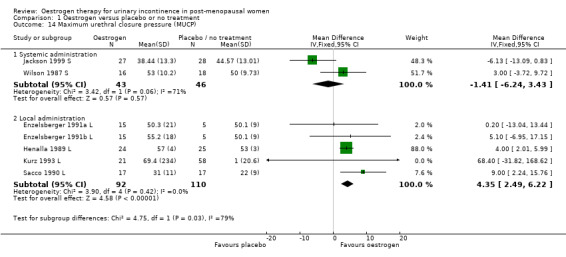

Systemic

The limited data available for the effects of systemic oestrogen administration versus placebo on maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP) (Analysis 1.14), volume at first urge to void (Analysis 1.15) and maximum bladder capacity (Analysis 1.16) showed no statistically significant difference between the two interventions.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 14 Maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 15 Volume at first urge to void.

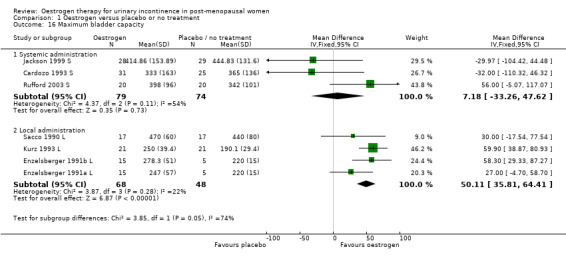

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 16 Maximum bladder capacity.

Local

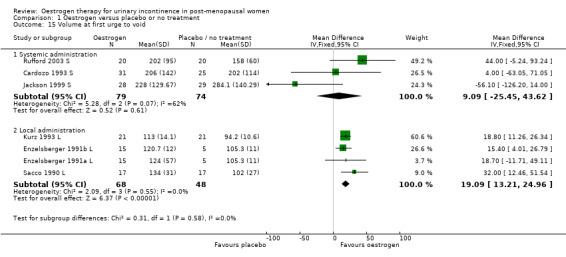

The data available for maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP) (RR 4.35, 95% CI 2.49 to 6.22) (Analysis 1.14), volume at first urge to void (RR 19.09, 95% CI 13.21 to 24.96) (Analysis 1.15) and maximum bladder capacity (RR 50.11, 95% CI 35.81 to 64.41) (Analysis 1.16) when comparing local oestrogen to placebo all tended to favour the oestrogen treated groups. The data for all three outcome measures were statistically significant.

Quality of life

One trial provided information about data from the Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (BFLUTS) questionnaire (Jackson 1999 S) and reported no significant difference between the trial groups. Another trial used the King's Healthcare Quality of Life Questionnaire, but no further information was given (Rufford 2003 S).

Socioeconomic measures

No data were available.

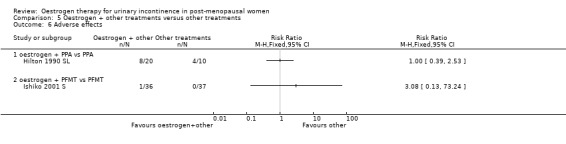

Adverse effects

One trial (Rufford 2003 S) compared systemic oestrogen against placebo and reported more adverse events in the placebo group, with the results being statistically significant (Analysis 1.17) (RR 13.00, 95% CI 1.87 to 90.21). No serious adverse events were reported with women in the trials experiencing mainly vaginal spotting, breast tenderness and nausea. These are detailed in the notes column in the Characteristics of Included studies table.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 17 Number with adverse effects.

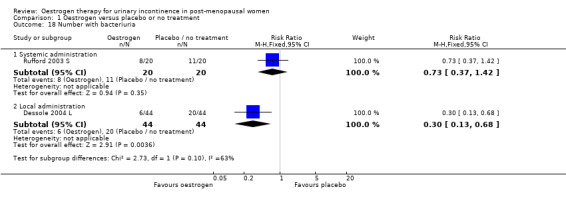

Number with bacteriuria

One small trial (Rufford 2003 S) compared systemic oestrogen to placebo and reported a higher incidence of bacteriuria in the oestrogen group.

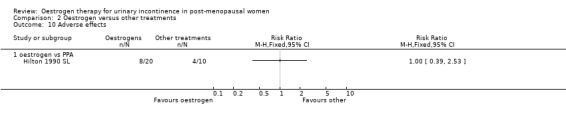

Comparison 2. oestrogen versus other treatment

Five trials compared oestrogens with other treatment, three with phenylpropanolamine (PPA) (Beisland 1984 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Walter 1990 S) and two with pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) or electrostimulation (Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L). All were limited to women with stress incontinence and only one used systemic administration (Walter 1990 S).

Oestrogen versus phenylpropanolamine (PPA)

The three trials that compared oestrogen with PPA included only 79 women in total (Beisland 1984 L; Hilton 1990 SL; Walter 1990 S). PPA is used in prescription and over‐the‐counter nasal decongestants and appetite suppressants, and has an alpha‐adrenergic mode of action. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in any of the outcomes for which data were available but the CIs were wide. There was some evidence of heterogeneity between the three trials and this may reflect the difference in the periods of active treatment (two versus four weeks). The results for the Beisland crossover trial are presented in the 'Other data' tables only.

Oestrogen versus pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT)

The two trials that compared local oestrogen with PFMT included 69 women (Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L). Both Henalla trials used conjugated equine oestrogen. Women's incontinence was less likely to improve with oestrogens than with PFMT in the two small trials. The combined data were statistically significant favouring PFMT (RR for lack of improvement in incontinence 2.30, 95% CI 1.50 to 3.52) (Analysis 2.6). There were not enough data for other outcomes or to show if there was a difference in maximum urethral closure pressure as measured by urodynamics.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus other treatments, Outcome 6 Number with incontinence not improved (objective observations).

Oestrogen versus electrostimulation

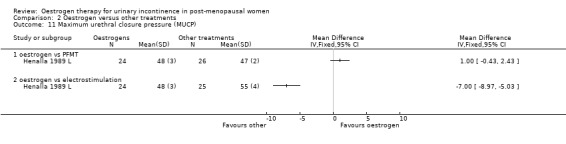

A single small trial included 49 women in the comparison of local oestrogen with electrostimulation (Henalla 1990 L). The result favoured electrostimulation over oestrogen in terms of a higher maximum urethral closure pressure as measured by urodynamics (WMD ‐7.00, 95% CI ‐8.97 to ‐5.03) (Analysis 2.11) although there was no statistically significant difference in terms of improvement in objectively observed incontinence (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.75) (Analysis 2.6).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus other treatments, Outcome 11 Maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP).

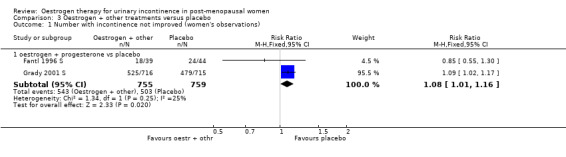

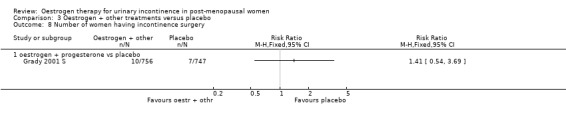

Comparison 3. oestrogen plus other treatment versus placebo

Progesterone was the only treatment tested as an addition to oestrogen in the four trials identified (Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S; Ouslander 2001 S). All four trials used conjugated equine oestrogen.

Oestrogen plus progestogen versus placebo

The four trials that compared the combination of oestrogen and progestogen versus placebo were conducted in contrasting groups of women.

The report by Grady (Grady 2001 S) was based on a subset of post‐menopausal women with urinary incontinence within a large trial of hormone replacement treatment for women with coronary heart disease, all of whom had an intact uterus.

The Hendrix trial included a subset of women with urinary incontinence from a trial where the main objective was to investigate the effects of hormone replacement treatment on prevention of coronary heart disease and bone fracture in post‐menopausal women (Hendrix (no hysterect) S); the women in this subset also had an intact uterus.

The women in the smaller trial reported by Fantl (Fantl 1996 S) were post‐menopausal and had stress incontinence only.

The women in the small trial by Ouslander (Ouslander 2001 S) were incontinent nursing home residents but no data were available for this trial with respect to any of the review outcomes.

When the data on no improvement in incontinence (women's observations) from three of the trials (Fantl 1996 S; Grady 2001 S; Hendrix (no hysterect) S) were combined using generic inverse variance, the net effect was that urinary incontinence in women treated with oestrogen plus progestogen was worse than in those on placebo; the result was statistically significant (RR for no improvement 1.11, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.18) (Analysis 3.2.1). The Grady trial received the highest weighting at 75.3% (Analysis 3.2.1) in the meta‐analysis due to less variance in the results. Both the Grady and Hendrix trials included women with all types of incontinence and all had an intact uterus. Fantl included only women with stress incontinence. There was no significant statistical heterogeneity. All three trials in the meta analysis used systemic conjugated equine oestrogen plus progestogen. No trials were found for this comparison, which addressed the effect of local administration.

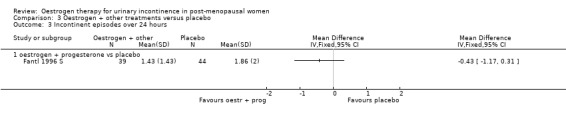

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen + other treatments versus placebo, Outcome 2 Incontinence not improved (generic inverse variance) (women's observations).

The report by Hendrix (Hendrix (no hysterect) S) reported that the relative risk of any urinary incontinence becoming worse was consistently higher in the group treated with oestrogen and progesterone compared with placebo (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.36). This effect was also seen for increased frequency of incontinence episodes (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.49) and for limitation of daily activities (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.32).

The Fantl study (Fantl 1996 S) recorded data on incontinent episodes in 24 hours, diurnal and nocturnal voids, and pad weight tests, but the data were too few to show any conclusive findings.

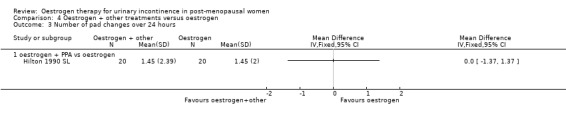

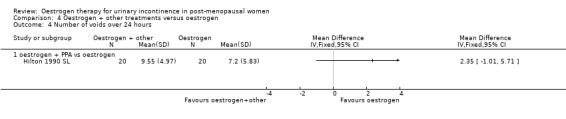

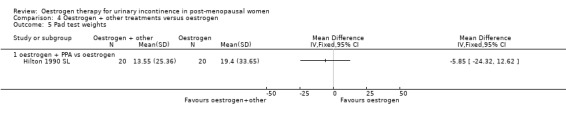

Comparison 4. oestrogen plus other treatment versus oestrogen

Six trials compared oestrogen plus other treatment with oestrogen alone. The other treatments were:

PPA (phenylpropanolamine) (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Ek 1980 S; Hilton 1990 SL; Kinn 1988 S);

benzidamine (Melis 1997 L);

naproxen (Blom 1995 S).

Four trials used systemic administration of oestrogen, one used the local route (Melis 1997 L) and one used different routes in different arms (Hilton 1990 SL) where data from the oestrogen arms have been combined for analysis.

Oestrogen plus PPA versus oestrogen

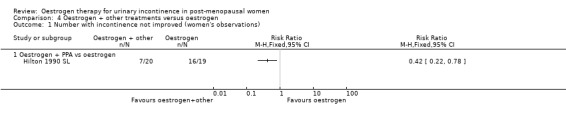

Usable data were available from only one trial (Hilton 1990 SL) and this involved only 20 women in each group. No statistically significant difference was seen for any outcome except improvement of incontinence, where the addition of PPA to oestrogen was better than oestrogen alone (Analysis 4.1.1) (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.78) but the CIs were wide. In two small crossover trials (Ahlstrom 1990 S; Kinn 1988 S) involving 53 and 60 participants, respectively, supplementing oestrogen with PPA resulted in marginally fewer incontinent women (Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen + other treatments versus oestrogen, Outcome 1 Number with incontinence not improved (women's observations).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen + other treatments versus oestrogen, Outcome 2 Number with incontinence not improved (women's observations) (cross‐over trials).

| Number with incontinence not improved (women's observations) (cross‐over trials) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | oestrogen + other drug | oestrogen |

| oestrogen + PPA vs oestrogen | ||

| Ahlstrom 1990 S | 17 out of 27 women | 21 out of 26 women |

| Kinn 1988 S | 14 out of 30 women | 21 out of 30 women |

Oestrogen plus benzidamine versus oestrogen

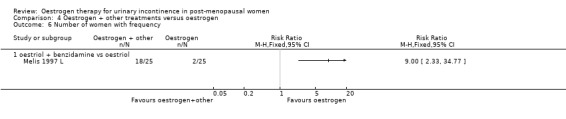

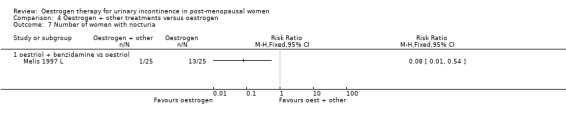

A single small trial (Melis 1997 L) suggested lower rates of frequency of voids (Analysis 4.6.2) and nocturia (Analysis 4.7.1) if benzidamine was added to oestrogen. However, the CIs were wide and there were no data for other outcomes.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen + other treatments versus oestrogen, Outcome 6 Number of women with frequency.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen + other treatments versus oestrogen, Outcome 7 Number of women with nocturia.

Oestrogen plus naproxen versus oestrogen

In another small crossover trial (Blom 1995 S) the addition of naproxen appeared to decrease the volume at the first urge to void (Analysis 4.9.1) although the decrease in the maximum bladder capacity was modest and not statistically significant (Analysis 4.10.1). There were no data for other outcomes.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen + other treatments versus oestrogen, Outcome 9 Volume at first urge to void (cross‐over trials).

| Volume at first urge to void (cross‐over trials) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | oestrogen + naproxen | oestrogen |

| oestrogen + PPA vs oestrogen | ||

| Blom 1995 S | 172 ml (SD 12) N=16 | 186 ml (SD 12) N=16 |

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen + other treatments versus oestrogen, Outcome 10 Maximum bladder capacity (cross‐over trials).

| Maximum bladder capacity (cross‐over trials) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | oestrogen + naproxen | oestrogen |

| oestrogen +other vs oestrogen | ||

| Blom 1995 S | 316 ml (SD 17) N=16 | 318 ml (SD 20) N=16 |

Comparison 5. oestrogen plus other treatment versus other treatment

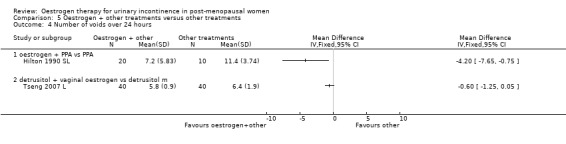

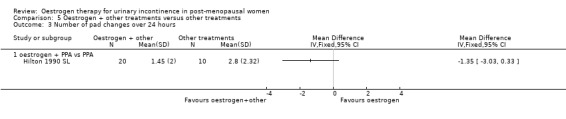

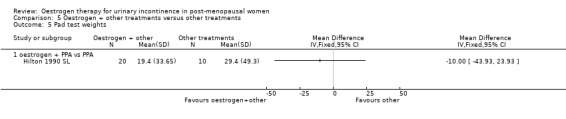

One small trial (Hilton 1990 SL) involving 30 women tested the addition of PPA to oestrogen in comparison with PPA alone. Women who also received oestrogen showed an improvement in incontinence (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.68) (Analysis 5.2) and around four fewer voids per day (Analysis 5.4) than with PPA alone. The other outcomes measured, number of pad changes (Analysis 5.3) and pad test weights (Analysis 5.5), were not significantly in favour of oestrogen supplementation and had wide CIs.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen + other treatments versus other treatments, Outcome 2 Number with incontinence not improved (women's observations).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen + other treatments versus other treatments, Outcome 4 Number of voids over 24 hours.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen + other treatments versus other treatments, Outcome 3 Number of pad changes over 24 hours.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen + other treatments versus other treatments, Outcome 5 Pad test weights.

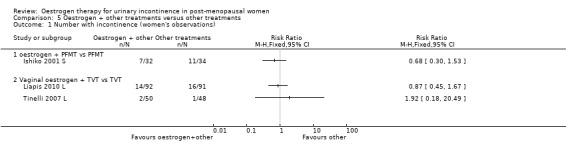

Another trial with 66 women evaluated the benefit of adding oestrogen to PFMT but was too small to demonstrate differences reliably (Ishiko 2001 S).

Tinelli (Tinelli 2007 L) compared tension free vaginal tape (TVT) with TVT plus vaginal oestrogen and reported no statistically significant difference for incontinence rates between the groups in this small study. Liapis (Liapis 2010 L) also compared TVT combined with vaginal oestrogen against TVT alone. The results state that treatment with vaginal oestrogen post‐operatively showed no reduction in urge incontinence when compared to the non‐treated group. Tseng (Tseng 2007 L) compared vaginal oestrogen plus detrusitol with detrusitol for overactive bladder and found that there was a slight increase in the number of voids over 24 hours in the oestrogen plus detrusitol group (RR ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.25 to 0.05) (Analysis 5.4).

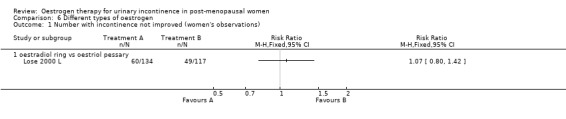

Comparison 6. different types of oestrogen

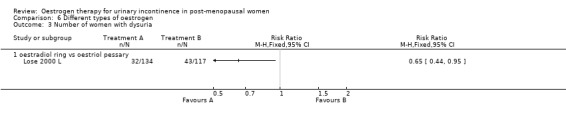

One trial directly compared different types of oestrogen. The trial carried out by Lose (Lose 2000 L) compared a vaginal oestradiol ring versus vaginal oestriol pessary.

Vaginal oestradiol (ring) versus vaginal oestriol (pessary)

Women preferred the oestradiol ring to the oestriol pessary (women's subjective assessment was markedly in favour of the oestradiol ring: 55% versus 14% grading it as 'excellent') (Lose 2000 L) and fewer women had dysuria (painful urination) (Analysis 6.3), but it was not clear whether this was due to the different type of oestrogen or the different delivery system.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Different types of oestrogen, Outcome 3 Number of women with dysuria.

The CIs were wide for all the other outcomes reported (Lose 2000 L).

Comparison 7. different routes of administration

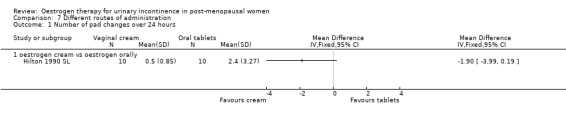

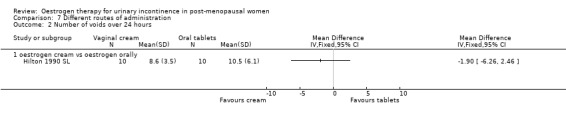

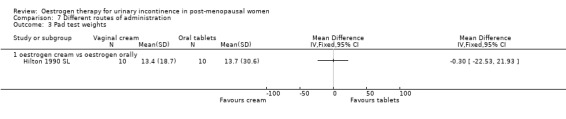

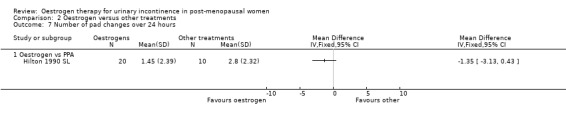

One small trial which directly compared oestrogen vaginal cream with oral tablets involved 20 women (Hilton 1990 SL). Although there were fewer voids and pad changes over 24 hours in the group treated with oestrogen cream, there was not enough evidence to reliably compare the two treatments on number of pad changes (Analysis 7.1), number of voids (Analysis 7.2) or pad test weights (Analysis 7.3).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Different routes of administration, Outcome 1 Number of pad changes over 24 hours.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Different routes of administration, Outcome 2 Number of voids over 24 hours.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Different routes of administration, Outcome 3 Pad test weights.

Comparison 8. high‐dose versus low‐dose oestrogen

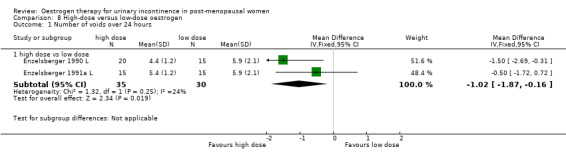

Two trials compared high‐dose with low‐dose oestrogen treatment for women with urgency urinary incontinence (Enzelsberger 1990 L; Enzelsberger 1991a L).

Women receiving the higher dose had significantly fewer voids per 24 hours (RR ‐1.02, 95% CI ‐1.87 to ‐0.16) (Analysis 8.1) and reduced number of voids at night (RR ‐1.80, 95% CI ‐2.36 to ‐1.24) (Analysis 8.2). Urodynamic measurements were only in favour of high‐dose treatment in terms of a higher maximum bladder capacity (WMD 35 ml, 95% CI 8.35 to 61.45) (Analysis 8.5).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 High‐dose versus low‐dose oestrogen, Outcome 1 Number of voids over 24 hours.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 High‐dose versus low‐dose oestrogen, Outcome 2 Number of nocturnal voids.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 High‐dose versus low‐dose oestrogen, Outcome 5 Maximum bladder capacity.

Adverse effects

The most common side effects were vaginal bleeding (about one in four women treated) and breast tenderness (about one in five women treated). Other side effects were not consistently reported, or not related to the study arm. In one trial, one women died of a myocardial infarction (Cardozo 2001 L) and in another one woman developed angina (Rufford 2003 S). However, these were not thought to be related to treatment with oestrogens.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The data from the small trials which evaluated local administration of oestrogen suggested that oestrogens may improve urinary incontinence. However, the data regarding systemic administration suggested that hormones (either oestrogen alone or in conjunction with progesterone) made incontinence worse. There was, however, too little evidence from a direct comparison of local versus systemic administration to assess this reliably. The data addressing the other comparisons in the review were relatively few.

The results of the small trials comparing local administration of oestrogen with placebo were generally consistent in suggesting better outcomes associated with oestrogen treatment. However, there was limited evidence from two small trials (Henalla 1989 L; Henalla 1990 L) that pelvic floor muscle training was more effective than local oestrogen treatment in the management of stress incontinence and from one small trial (Hilton 1990 SL) that local oestrogen plus PPA was more effective than local oestrogen alone in stress incontinence. Data from the Hilton trial also showed that oestrogen plus PPA was more effective than PPA alone. PPA is used in prescription and over‐the‐counter cold and cough preparations and appetite suppressants and has an alpha‐adrenergic action, but it has been associated with an increased risk of stroke in younger women (Kernan 2000).

Two very large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving systemic hormone replacement therapy (Grady 2001 S; Hendrix 2005 S), where the main objectives were to investigate effects such as cardiac events and bone fractures, reported that both oestrogen treatment alone (Hendrix (hysterectomy) S) and combined with progestogen (Grady 2001 S; Hendrix (no hysterect) S) made incontinence worse. Both studies used conjugated equine oestrogen. The result for oestrogen versus placebo is heavily weighted by the larger Hendrix trial. All the women in this subset had had a hysterectomy. Furthermore, in another subset of one of these trials (Hendrix 2005 S) a group of women who were continent at baseline reported more incontinence after one year of treatment with oestrogen plus progestogen compared with women on placebo treatment (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.52 for women with a uterus; RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.71 for women after hysterectomy and treated with oestrogen alone). This is consistent with other evidence about the effects of progesterone on urinary symptoms (Benness 1991). Therefore, post‐menopausal women who are considering receiving systemic hormone replacement therapy for reasons other than incontinence should be warned that they may develop urinary incontinence or their urinary symptoms may get worse.

In summary, local rather than oral preparations may reduce the risks of long‐term treatment. There was some evidence from three small trials that local (vaginal) administration might improve continence, whereas evidence from the two large trials suggested that systemic administration made it worse.

Adverse effects

There were no serious adverse effects related to treatment for incontinence reported in the trials; however, the reader should consider longer‐term side effects of hormone therapy presented in other reports (Marjoribanks 2012). The most common side effects were vaginal bleeding (about one in four women treated) and breast tenderness (about one in five women treated). There are, however, concerns about risks of unopposed oestrogens (continuous oestrogens without intermittent progestogen supplementation), particularly amongst women who have an intact uterus. Such women may develop endometrial hyperplasia, which increases the risk of endometrial cancer. In addition, the risk of breast cancer is increased by prolonged use of oestrogens (for example for five years) (Marjoribanks 2012) and women who have predisposing factors for deep venous thrombosis are also advised that oestrogens may increase their risk (BNF 2002). Furthermore, combined continuous hormone replacement therapy (HRT) significantly increases the risk of venous thrombo‐embolism or coronary events (after one year's use), stroke (after three years), breast cancer, gall bladder disease and dementia (Marjoribanks 2012). Long‐term oestrogen‐only HRT significantly increased the risk of venous thrombo‐embolism, stroke and gall bladder disease but did not significantly increase the risk of breast cancer. On the other hand, there is some evidence that oestrogen use before the age of 60 years is relatively safe (Rossouw 2007).

In most of the reviewed trials, oestrogen was not given for prolonged periods and only three trials gave any information about the women after the end of treatment. One risk of unopposed oestrogen (oestrogen alone) is endometrial cancer. Pending further research, women with an intact uterus should receive combined oestrogen and progestogen for limited periods. Women who have had a hysterectomy can receive oestrogen alone but again this should be for limited periods due to the risks already mentioned (Marjoribanks 2012).

PPA has been associated with an increased risk of stroke in younger women, however this adverse effect was not reported in the women involved in the included trials.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

While the data from the other comparisons were generally consistent with the findings for oestrogen alone (for example a higher dose of oestrogen appeared to have a greater benefit on incontinence than a lower dose using local administration) they were too few to allow these other questions to be addressed reliably. In particular, there was little direct evidence to address the choice of oestrogen type (oestriol, oestradiol, oestrone, quinestradiol or conjugated equine oestrogens) and the alternative methods of delivery (oral, subcutaneous implant, transdermal cream, gel or patch, vaginal cream, pessary or ring, or intravesical).

The conflicting evidence on the effects of oestrogens while on treatment together with the concerns about longer‐term risks of unopposed oestrogens (oestrogen alone) raise questions about length of treatment. No trials addressed the question of whether the effects of oestrogen therapy were sustained after treatment was stopped but this seems biologically unlikely.

Quality of the evidence

Both the Hendrix (Hendrix 2005 S) and Grady (Grady 2001 S) trials were of good quality and had the longest duration of follow up (one year in the Hendrix trial, four years in the Grady trial). The Grady trial (Grady 2001 S) included only women with heart disease so the results may not be generalisable, although the results from the Hendrix trial concur with the Grady trial. In the Hendrix trial, women on active treatment may have more visits to the doctor for side effects such as vaginal bleeding and hence would have been more likely to report incontinence symptoms, but there is no evidence for this. There was differential withdrawal at one year within the Hendrix trial, with 9.7% of women taking oestrogen plus progesterone and 6.6% taking placebo stopping taking the medication.