Abstract

Multiple features distinguish the mitochondria of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients from those of unaffected individuals. The causes and consequences of these differences are informed by the recent finding by Fleck et al. that pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein 1 (PTCD1) gene variants associate with AD. This suggests a proximal or initiating role for mitochondria in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mitochondria, PTCD1

One way to interrogate the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is to compare gene data of affected and unaffected individuals. Using this strategy, in 1991 investigators focused on the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene in autosomal dominant kindreds and identified a disease-segregating variant. Shortly thereafter, linkage analysis approaches implicated a role for two presenilin (PSEN) genes in autosomal dominant cases and revealed associations between APOE population variants and late onset AD (LOAD) [1].

The development of genome wide association studies (GWAS) at the century’s turn facilitated identification of additional LOAD-relevant genes. The list of recognized genes grew to over 30 as analyzed cohorts increased in size and GWAS chips incorporated more variants [2]. Sorting the genes on this list into functional categories defined specific areas of biologic interest, including cholesterol/lipid metabolism, immune response, and endocytosis. Because GWAS chips generally include common variants, though, these studies likely missed genes with associations driven by rare variants.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) provides more comprehensive gene detail and is more suited than chips for detecting rare variant associations. Recently, Fleck et al. analyzed WES data using gene burden testing in nearly 8,000 samples from the Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project (ADSP) and found rare variants in the pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein 1 (PTCD1) gene associated with increased LOAD risk [3]. The lead single nucleotide variant, rs35556439, did not meet strict genome-wide significance in the ADSP analysis likely due to low power, but was nominally associated with AD (OR=1.6, p = 4.3e−6) in a whole-exome microarray analysis of three independent datasets with a combined sample size of 49,493.

Because the PTCD1 gene product localizes to mitochondria, the authors evaluated the functional consequences of PTCD1 knock out (KO), knock down (KD), and single nucleotide variation (rs35556439, which causes an R113W substitution). These cell culture-based experiments revealed PTCD1 KO profoundly reduced cell oxygen consumption, increased glycolysis flux, and perturbed mitochondrial structure. KO cells lacked 16S ribosomal RNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encoded electron transport chain (ETC) subunits, which suggests the PTCD1 protein supports translation of mtDNA-derived mRNAs. In cultured neurons, KD resulted in lower ATP levels and altered synaptic activity. Changes in R113W cells were subtler, though still detectable. Together, the genetic and functional data from this report argue PTCD1 variants influence AD risk by affecting mtDNA gene translation.

The authors point out that mitochondrial dysfunction caused by PTCD1 missense variants, including rs35556439, may impair neuron and microglia oxidative phosphorylation. This could reduce microglial clearance of beta amyloid (Aβ) and facilitate its deposition. Such a scenario is consistent with the amyloid hypothesis, and echoes prior speculation that TREM2 variants might promote AD by impeding microglial bioenergetics and, consequently, Aβ phagocytosis [4]

Regardless of whether this mechanism is correct, the Fleck et al. study indicates mitochondrial pathology in AD can exist independent of Aβ. AD mitochondrial abnormalities are pervasive, and AD patient-derived mitochondria differ from control subject mitochondria on multiple parameters [5, 6]. For example, AD patient mitochondria are on average smaller and the fission-fusion balance shifts towards fission. Activities of some Krebs cycle enzymes and pyruvate dehydrogenase are altered, and cytochrome oxidase activity is reduced. There is less PCR-amplifiable mtDNA, and mtDNA deletions and oxidative modifications increase in AD brain. The basis and relevance of these and other differences are unclear, but available data provide insight. Mitochondrial alterations, as observed within the brain, are also present outside the brain, which implies that the observed phenomena are not simply neurodegeneration-induced. Mitochondrial perturbations persist in cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) cell lines generated via mtDNA transfer [7], which indicates mtDNA contributes at least partly to observed functional differences. Epidemiologic and endophenotype studies further suggest a potential heritable mtDNA contribution. The Fleck et al. study is also consistent with the possibility that AD mitochondrial dysfunction arises and exists independent of an amyloid cascade.

Genetic association approaches identify disease-relevant loci in an unbiased manner. Extending an association from a locus to a gene can introduce bias, although the use of WES in the Fleck et al. study somewhat reduces this concern. To this point, PTCD1 is within 1 megabase of the AD-associated ZCWPW1 locus but was not previously considered a candidate gene. Also, because proteins can have multiple functions, assigning biological significance can introduce bias. In this case, the mitochondrial localization of PTCD1 suggests the coding variants very likely influence AD risk through effects on mitochondrial function.

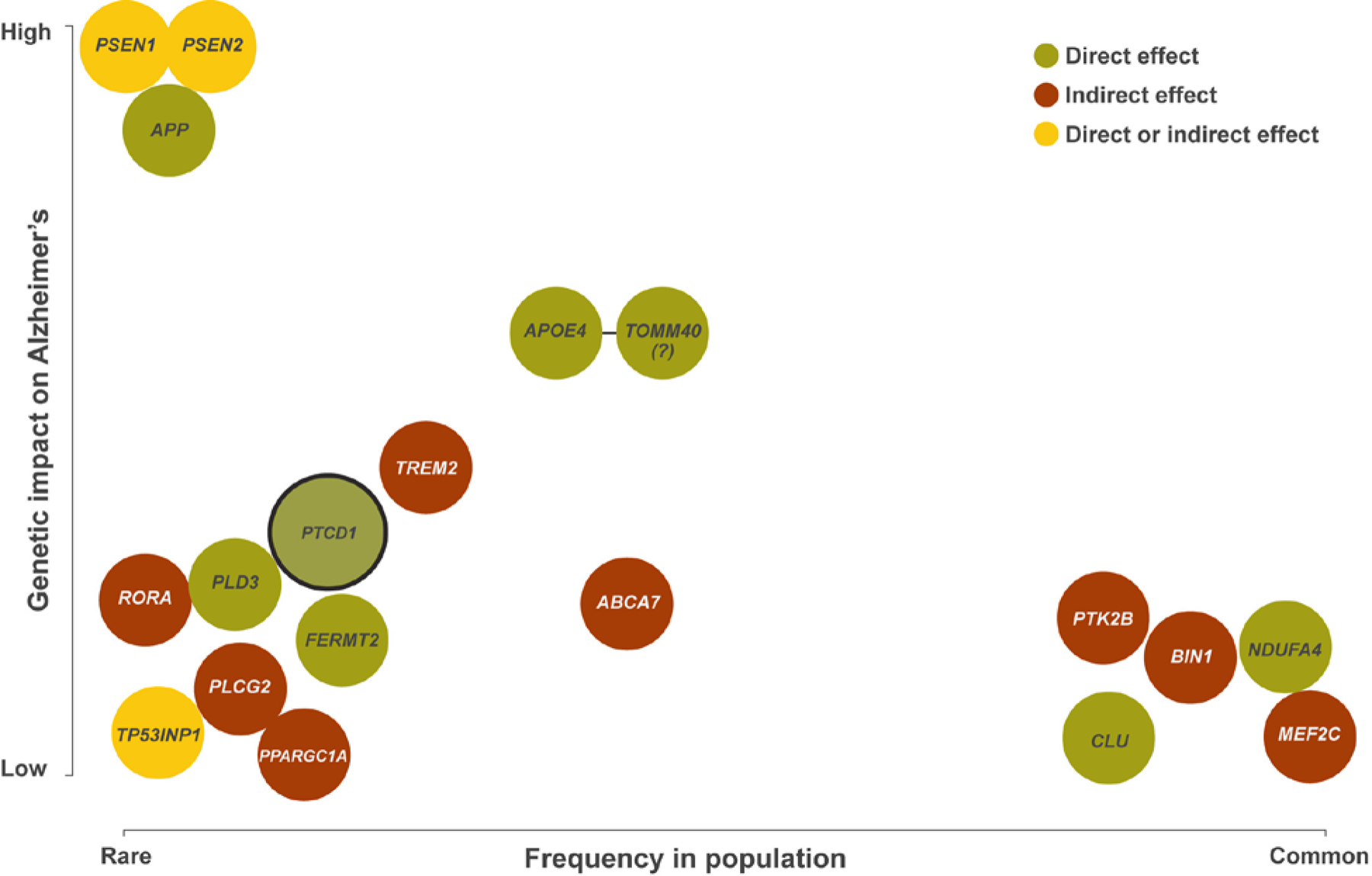

AD-associated PTCD1 variants are rare, which could imply mitochondria infrequently influence the disease. We feel there is reason to question this position. It is hard to disentangle mitochondria from other recognized biological processes such as lipid/cholesterol homeostasis and immune responses. Notably, APOE4-encoded peptides yield a mitochondria-targeted fragment that lowers cytochrome oxidase activity [8]. Mitochondria, therefore, may potentially mediate the APOE-AD association. The products of other AD-associated genes are also found in or on mitochondria, while others remotely influence mitochondrial function. Figure 1 shows AD-associated genes that could plausibly affect, directly or indirectly, mitochondrial function. Most of these genes were previously assigned to other biological modules, but it is perhaps worth examining their roles from a mitochondrial perspective.

Figure 1. AD-associated genes whose products can reportedly localize to mitochondria or influence mitochondrial function.

This figure includes genes said to associate with AD, usually through mechanisms unrelated to mitochondria (PTCD1 is the obvious exception), but which could plausibly affect mitochondria. The figure indicates how relatively common the variant form of the gene is in the general population (x-axis), and the relative magnitude of the impact the variant form of the gene appears to have on disease risk (y-axis). Whereas locus detection is unbiased, assignment of the responsible gene is not (in one recent AD GWAS 18 of 24 loci had a gene encoding a mitochondrial-localized protein within a 1 megabase window) [2]. Similarly, biases can be involved in the proposed biologic explanations for why a specific gene or its product influences AD risk. Current studies indicate, or are consistent with the possibility, that multiple AD-associated genes directly or indirectly affect mitochondrial function. The genes shown here were detected through a variety of approaches including linkage, GWAS, WES, and gene-based analysis. A green background indicates a potential direct effect on mitochondria, a red background indicates a potential indirect effect, and a yellow background indicates potential direct and/or indirect effects. TOMM40 is indicated with a question mark because TOMM40 is in linkage disequilibrium with APOE, and it is unclear whether TOMM40 variants independently impact AD risk.

In addition to PTCD1, over 1000 nuclear genes generate mitochondria-localized proteins. AD GWAS interrogate variants in many of these genes. Investigators recently used AD GWAS data to define a mitochondrial polygenic risk score (PGRS), which in turn was found to interact with mtDNA haplogroups to influence AD risk [9]. Efforts are underway to define an mtDNA-specific PGRS and investigate interactions with the nuclear PGRS on AD risk.

Studies that elucidate the effects of PTCD1 gene variants in aging and/or AD transgenic animal models are needed. Regardless, the Fleck et al. study has considerable implications for how we approach the role of mitochondria in AD. While many investigators agree mitochondria are relevant, some view them as minor players while others envision a critical role or even postulate a “mitochondrial cascade” that leads the onset of AD pathogenesis [10]. What mitochondrial cascade proponents lacked until now, though, was a genetic smoking gun. In the AD paradigm wars, PTCD1 could prove to be the smoking gun that kicks off an arms race.

Acknowledgments

JP is supported by the National Institute on Aging (AG054617, AG05142). SJA is supported by the JPB Foundation. RHS is supported by the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center (AG035982), AG060733, AG061194, and AZ170111.

References

- 1.Karch CM and Goate AM (2015) Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry 77 (1), 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunkle BW et al. (2019) Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet 51 (3), 414–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleck D et al. (2019) PTCD1 Is Required for Mitochondrial Oxidative-Phosphorylation: Possible Genetic Association with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurosci 39 (24), 4636–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulland TK et al. (2017) TREM2 Maintains Microglial Metabolic Fitness in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 170 (4), 649–663.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swerdlow RH (2012) Mitochondria and cell bioenergetics: increasingly recognized components and a possible etiologic cause of Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 16 (12), 1434–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swerdlow RH et al. (2017) Mitochondria, Cybrids, Aging, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 146, 259–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swerdlow RH et al. (1997) Cybrids in Alzheimer’s disease: a cellular model of the disease? Neurology 49 (4), 918–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HK et al. (2011) Apolipoprotein E4 domain interaction mediates detrimental effects on mitochondria and is a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 286 (7), 5215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews SJ et al. (2019) Mitonuclear interactions influence Alzheimer’s disease risk. bioRxiv, 654400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swerdlow RH et al. (2014) The Alzheimer’s disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis: progress and perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842 (8), 1219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]