At the end of December, 2019, a new disease of unknown aetiology appeared in Wuhan, China. It was quickly identified as a novel betacoronavirus, and related to SARS-CoV and a number of other bat-borne SARS-like coronaviruses. The virus rapidly spread to all provinces in China, as well as a number of countries overseas, and was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the Director-General of the World Health Organization on 30 January 2020. This paper describes the evolution of the outbreak, and the known properties of the novel virus, SARS-CoV-2 and the clinical disease it causes, COVID-19, and comments on some of the important gaps in our knowledge of the virus and the disease it causes. The virus is the third zoonotic coronavirus, after SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but appears to be the only one with pandemic potential.

An outbreak of cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology in the city of Wuhan in Hubei Province, China, was announced and notified to the World Health Organization (WHO) by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission on 31 December 20191. The outbreak was linked epidemiologically to the Hua Nan seafood and wet animal wholesale market in Wuhan, and the market was subsequently closed on 1 January 2020. A week later, on 7 January, the isolation of a previously unknown betacoronavirus was reported as the aetiological agent.

Wuhan is a city of 11 million inhabitants and is a major transport hub, and over the ensuing weeks the virus spread to other provinces in China and later to an increasing number of other countries. This spread prompted the WHO Director-General to establish an Emergency Committee (EC) under the International Health Regulations (IHR). The EC recommended that the outbreak constituted a public health emergency of international concern at its meeting on 30 January2. In so doing, the Committee believed that it was still possible to interrupt virus spread, provided that countries put in place strong measures to detect disease early, isolate and treat cases, trace contacts, and promote social distancing measures commensurate with the risk.

The city of Wuhan was placed in quarantine by the Chinese Government on 23 January, stopping all rail, road and air transport out of the city. The quarantine was subsequently extended to a further 17 cities in Hubei Province, affecting over 57 million people, which was particularly challenging as it came two days before the Chinese New Year, the most important festival in the country, and traditionally the peak traveling season. Since then there have been increasing measures to control and manage the epidemic within China, and the introductions of numerous travel restrictions by other countries that either have had cases or are trying to prevent entry.

Early events in determining the identity and origin of the novel coronavirus

Whole virus genome sequences were obtained either directly from patient samples or from cultured viruses from a number of patients hospitalised with pneumonia in Wuhan, showing that the aetiological agent was a betacoronavirus belonging to a new clade in subgenus Sarbecovirus in the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily3–7. Phylogenetic studies of the new virus showed it shared about 79% nucleotide homology with SARS-CoV4–7, as well as to two SARS-like coronaviruses isolated from Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus) in Zhoushan, with which it shared 89% nucleotide homology3,5–8, and to a third SARS-like coronavirus from an Intermediate horseshoe bat (R. affinis), with which it shared 96% nucleotide homology4,9. Based on established practice, the new virus was named SARS-CoV-2 by the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses10, and the disease it causes as COVID-19 by WHO11.

How this virus moved from animal to human populations is yet to be determined. The outbreak clearly began epidemiologically at the Wuhan market, and a number of environmental samples from around the live animal section of the market were subsequently found to be positive for SARS-CoV-212, but based on current evidence, it may not have actually emerged in the market. The earliest recognised case of infection with SARS-CoV-2 was an elderly and infirm man who developed symptoms on 1 December 2019. None of his family members became infected, and the source of his virus remains unknown13. Furthermore, 14 of the first 41 cases had no contact with the seafood market13. In another report, five of the first seven cases of COVID-19 had no link to the seafood market14. Thus, it seems very likely that the virus was amplified in the market, but the market might not have been the site of origin nor the only source of the outbreak. A recent phylo-epidemiological study has suggested that the virus was circulating but unrecognised in November, and was imported to the seafood market from elsewhere, where it subsequently was amplified15.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) was known to be the cell receptor for SARS-CoV, and also for some SARS-like bat coronaviruses16. Sequence studies found that the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was sufficiently similar to that of SARS-CoV to indicate it could efficiently use the human ACE2 receptor for entry to human cells6,7. Infectivity experiments were undertaken with HeLa cells expressing or not expressing ACE2 from humans, bats, civets, pigs and mice, and the results confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 virus was able to use entry receptors on all ACE2-expressing cells other than mice5. Molecular modelling has indicated that the binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE-2 may be even higher than that of SARS-CoV and it may therefore be more efficient at infecting human cells17. Evidence from the sequence analyses clearly indicates that the reservoir host of the virus was a bat, probably a Chinese or Intermediate horseshoe bat, and it is probable that, like SARS-CoV, an intermediate host was the source of the outbreak. To ensure that future cross-species transmission events of this new virus don’t occur again in the future, it is important to identify the reservoir and intermediate wildlife hosts. The closest known wildlife sequence to SARS-CoV-2 remains the sequence from the virus isolated from an Intermediate horseshoe bat, but there were significant differences in the receptor-binding domain between the two viruses. Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica) have been suggested as potential intermediate hosts, and SARS-like viruses have been identified in pangolins seized in anti-smuggling operations in southern China, but they only shared about 85–92%% homology with SARS-CoV-218. No other possible intermediate wildlife host has been proposed at this time.

Next generation sequencing (NGS) was carried out on lung lavage samples from up to 17 patients between 24–30 December 2019 that would have demonstrated the presence of a SARS-related coronavirus3–7, but this information was not widely available until a sequence was reported on 12 January 2020. Interestingly, this was the first time that NGS had alerted the world to a new zoonotic virus before the virus had been isolated, and it suggests that a new procedure for reporting outbreaks based on NGS rather than pathogen isolation and identification needs to be considered19. The resulting information flow was a great improvement over the experience with SARS-CoV in 2003, but it is important to continue improving this as the lack of the earliest possible information about the sequences slowed down the development of diagnostics and preparedness capacity. This lack of early information may have extended to case notifications, as no cases were reported between 1 and 17 January 2020, but modelling suggested there may have been over 450 cases unreported in that time20, and indeed a number of such cases were subsequently confirmed retrospectively14.

Transmission

Human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has been widely shown in health care, community and family settings. The dominant mode of transmission is from the respiratory tract via droplets or indirectly via fomites, and to a lesser extent via aerosols. In addition, as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV can infect the human gastrointestinal tract21,22, it has been suggested that faecal-oral spread may occur for SARS-CoV-223. The reproduction number (Ro) is generally thought to be between 2.0 and 2.820,24–27, although higher reproduction numbers have been suggested in some reports. The mean incubation time appears to be between 4.75 and 7 days20,23,24,26,28, ranging from 3 days to an upper limit of around 11–14 days. There is increasing knowledge about the virus load. In one study of symptomatic patients, higher viral loads were detected soon after symptom onset, with the viral loads higher in the nose than in the throat. In a single asymptomatic patient, the viral load was similar to the symptomatic patients29. In a second and more detailed study, the virus load was investigated over consecutive days in two patients from the time of their hospitalisation, with serial samples throat swabs, sputum, urine and stools. The viral loads peaked around 5–6 days after symptom onset, with 104 to 107 copies/mL. The authors also studied the viral loads in throat swabs, sputum and stool samples in other patients, and found viral loads were as high as 1011 copies/mL in throat samples, but with a median of 7.99 × 104, and 7.52 × 105 in sputum. In addition, virus was detected by RT-PCR in stools from 9 of 17 confirmed cases, but at titres lower than in respiratory samples30. Several studies have indicated that transmission may occur during the incubation period31,32 and from asymptomatic or very mild infections29,33,34.

There are a number of important questions still to be answered about the transmission dynamics. These include information about the infectivity during the incubation period; the length of time and virus load during incubation and during the symptomatic period of virus shedding; the incidence and infectiousness of asymptomatic cases, the risk of vertical transmission from mother to fetus35, and other modes of transmission, such as from faeces, saliva and urine. There is some evidence that virus can be isolated from saliva36 and while the initial family cluster found no evidence of virus in stools or urine8, it has since been detected in faeces by PCR in other patients30,37,38 and cultured in one patient, but there has been no evidence of virus in urine. The number of mild or asymptomatic cases has not been determined and relatively few cases have been recorded, but it is probable that current figures only see the tip of the iceberg, and many cases remain undiagnosed19. They pose the greatest threat for increased virus spread27. Information is also needed on the stability of the virus in the environment to better determine transmission risks, and especially the survival of the virus in aerosols and on hard surfaces under different conditions of temperature and humidity.

Clinical features

It has become clear that asymptomatic infections and minimally symptomatic infections occur with this virus. Exactly how frequently is not yet known as that requires serological studies that have yet to be undertaken. The initial reports of the illness were heavily biased to more severe and hospitalised cases in China, and as the number of confirmed cases has increased within China and elsewhere, a clearer picture has emerged. The commonest clinical features are fever plus a respiratory illness, and studies have reported fever in 80–99% of cases, dry cough in 48–76% of cases, fatigue or myalgia in 44–70% of cases, and dyspnoea in 30–55% of cases. Other relatively frequent manifestations include anorexia and productive cough, and less frequently, headache, diarrhoea, nausea, dizziness and vomiting13,39,40. Severe illness and death are more likely to occur in older individuals, and possibly in those with pre-existing clinical illness such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and malignancies.

The case fatality rates have varied depending on the population affected. Initial estimates that were based on severely ill patients were high, but more recent estimates are around 2.3% on average, but significantly higher in the elderly and particularly those aged 80 years and over41. As many milder or asymptomatic infections are likely to have been missed, the mortality rate is expected to be lower than published figures as more information becomes available. Disease in paediatric patients appears to be rare, and when it occurs, very mild, but the role of children in transmission remains unknown.

More extensive and detailed studies are needed to understand the full spectrum of illness caused by this virus, the pathogenesis of disease, especially the lung disease, and the longer-term morbidity in survivors. The possibility of persistent and recurring infections, especially in immunocompromised patients, is unknown; we still have very limited data on the importance of pre-existing morbidities; more information is urgently needed on the disease in pregnancy and the potential for infection of the fetus; and we don’t understand the effect of past exposure to other coronaviruses on modifying disease severity.

Diagnostic tests

Clinical diagnosis has largely been based on clinical and exposure history, and laboratory and chest imaging findings. The laboratory findings will vary with the severity of disease, but a low lymphocyte count is common and persisting low counts is associated with poorer outcomes13,39,40. Testing for other respiratory pathogens should be undertaken to exclude viral and bacterial co-infections.

Detection of the virus has been based on PCR, with various assays directed particularly at the envelope (E), RdRp, spike protein (S) and nucleocapsid (N) genes. In-house assays are in use in a number of Public Health Laboratory Network (PHLN) member laboratories, with continual ongoing evaluation. In addition, there are several commercially available assays with claimed capacity for detection of SARS-CoV-2 that are also being evaluated. Virus can be found in the upper respiratory tract in nearly all patients beginning at or just before the onset of clinical illness29. The preferred samples are combined nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs and if they have a productive cough, also sputum. In patients with lower respiratory tract infections, virus may be detectable in sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage samples even if undetectable in the upper respiratory tract. Virus can be cultured relatively easily in a number of cell lines, including Vero cells, but requires a PC3 containment laboratory. Virus identification can be confirmed by sequencing if necessary, and a large number of partial and whole genome sequences are available via GISAID and GenBank. PCR tests have become increasingly available since about 25 January, but due to the rapid spread in China and the huge number of cases access to timely and accurate testing has been problematic, especially in the early stages, making it difficult to ascertain the true extent of virus infections and illness42.

Detailed PHLN recommendations for testing and for laboratory biosafety requirements within Australia are available in the Virology Appendix of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units43. However, tests are still being developed and evaluated, and we cannot yet confidently identify the best targets for PCR. Continual re-evaluation is required to identify any genetic drift that may affect test sensitivity. We also need to be able to transfer the tests onto platforms that can be delivered outside major laboratories, in resource poor settings, near to the patient, and quickly. The lack of serological assays hampers our ability to understand the true epidemiology of this virus and its impact, and to identify PCR-negative infections.

Therapeutics and vaccines

There are no proven or registered therapeutics or vaccines for COVID-19 infection at this time. Treatment is largely supportive44, though a number of therapeutics are under investigation with some undergoing clinical trials in China and elsewhere. Of particular interest currently are the HIV protease inhibitor combination lopinavir/ritonavir and a new broad-spectrum antiviral agent called remdesivir, which has shown promising activity against MERS-CoV in animal models. Combinations of these with interferon-β and/or ribavirin are being considered, while other groups are looking at other antivirals, convalescent plasma, and monoclonal antibodies.

Work on vaccines is also well underway, although it is unlikely that a vaccine will be available for at least 18 months. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI) is currently funding four vaccine initiatives in collaboration with the WHO. One of these is at The University of Queensland where Prof Paul Young, and Drs Keith Chappell and Dan Watterson are using their novel and exciting ‘molecular clamp’ technology to develop a vaccine. This work is being carried out in collaboration with CSIRO’s vaccine manufacturing plant in Clayton, and also partly funded by CSL Ltd. This Australian collaboration is hoping to have the vaccine ready for use before the end of 2021.

Current status

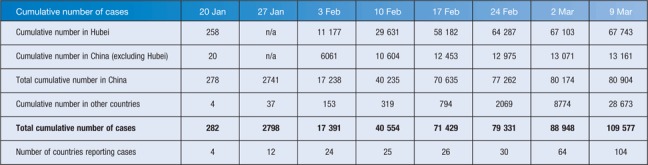

The international public health response to COVID-19 has largely been based on measures that have proved successful for many other outbreaks over past decades – rapid identification, management and isolation of cases; identification and follow up of contacts; quarantine measures; social distancing; infection prevention and control in health care settings; community containment; and transparent risk communication; as well as a 14-day quarantine period on travellers from China or who have had links to ongoing transmission sites or known cases, such as the cruise liner in Japan. Australia’s response has been similar, and to date has been moderately successful in limiting the number of chains of transmission in NSW, Queensland and Victoria, whereas most cases elsewhere have been in returning travellers or their close contacts. Table 1 shows cumulative cases in Hubei, elsewhere in China, and in other countries on a weekly basis between 21 January and 9 March, and shows the rapid rise in cases in China, particularly in Hubei Province, followed by a slowing down over the past 2 weeks, and a continuing rise in cases outside China with more and more countries reporting cases. As of 9 March, 105 countries had reported cases, but only three countries accounted for nearly 75% of the cases; South Korea with 7382 cases, Italy with 7375 cases, and Iran with 6566, and cases have been reported from all continents except Antarctica45. It has been suggested that up to half of COVID-19 cases exported from mainland China have remained undetected worldwide, and that 40% of travellers, largely asymptomatic, mild or pre-symptomatic travellers, were not detected at airports, potentially resulting in multiple chains of as yet undetected human-to-human transmission outside mainland China46,47. Although WHO finally called the COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March, in many respects it had already begun. This was presaged by the observation that more new cases were reported from the rest of the world than from China for the first time on 28 February, and in addition, secondary and tertiary chains of transmission have been reported in increasing numbers of countries. The Australian Government has already recognised this, and has instituted its emergency response plan and is now operating on the basis that the pandemic is here.

Table 1. . Cumulative cases of COVID-19 on a weekly basis from 21 January to 29 February 2020, for Hubei Province, for the rest of China, and for other countries.

| Cumulative number of cases | 20 Jan | 27 Jan | 3 Feb | 10 Feb | 17 Feb | 24 Feb | 2 Mar | 9 Mar |

| Cumulative number in Hubei | 258 | n/a | 11 177 | 29 631 | 58 182 | 64 287 | 67 103 | 67 743 |

| Cumulative number in China (excluding Hubei) | 20 | n/a | 6061 | 10 604 | 12 453 | 12 975 | 13 071 | 13 161 |

| Total cumulative number in China | 278 | 2741 | 17 238 | 40 235 | 70 635 | 77 262 | 80 174 | 80 904 |

| Cumulative number in other countries | 4 | 37 | 153 | 319 | 794 | 2069 | 8774 | 28 673 |

| Total cumulative number of cases | 282 | 2798 | 17 391 | 40 554 | 71 429 | 79 331 | 88 948 | 109 577 |

| Number of countries reporting cases | 4 | 12 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 30 | 64 | 104 |

Final comments

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans, and the third zoonotic virus after SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Bats are the reservoir hosts of a number of additional novel coronaviruses, particularly Chinese horseshoe bats, and a number of these novel coronaviruses can efficiently use multiple orthologs of the SARS receptor, human ACE2, and replicate efficiently in primary human airway cells and achieve in vitro titres equivalent to epidemic strains of SARS-CoV48,49. This indicates that other potential cross-species events could occur in the future. There is therefore a strong reason to ban unregulated wild animal sales in Chinese wet markets, particularly exotic species, both from a public health perspective and for ecological reasons. Such a ban would be difficult to instigate for cultural reasons, but China’s top legislative committee on 24 February 2020, passed a proposal to ban all trade and consumption of wild animals. If this is legislated as a permanent ban, it might help reduce the risk of another novel virus emerging from wildlife in China in the future.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific funding.

References

- Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (2019) Report of clustering pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan City. http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989 [in Chinese].

- World Health Organization (2020) Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Situation Report 11. 31 January 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200131-sitrep-11-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=de7c0f7_4 (accessed 21 February 2020).

- Zhu N., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L.L., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: a descriptive study. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F., et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceraola C., et al. Genomic variance of the 2019-nCoV coronavirus. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya A.E., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020) Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Situation Report 22. 11 February 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200211-sitrep-22-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=fb6d49b1_2 (accessed 22 February 2020).

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) China’s CDC detects a large number of new coronaviruses in the South China seafood market in Wuhan. http://www.chinacdc.cn/yw_9324/202001/t20200127_211469.html (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Huang C., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.B. et al (2020) Decoding evolution and transmissions of novel pneumonia coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) using the whole genomic data. 10.12074/202002.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ge X.Y., et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013;503:535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., et al. Structure analysis of the receptor binding of 2019-nCoV. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T.T.Y., et al. Identification of 2019-nCoV related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins in southern China. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.13.945845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L-F., et al. From Hendra to Wuhan: what has been learned in responding to emerging zoonotic viruses. Lancet. 2020;395:e33–e34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30350-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., et al. Estimating the unreported number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) cases in China in the first half of January 2020: a data-driven modelling analysis of the early outbreak. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:388. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W.K., et al. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., et al. Human intestinal tract serves as an alternative infection route for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:eaao4966. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling B.J., Leung G.M.2020Epidemiological research priorities for public health control of the ongoing global novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Euro Surveill. 25 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.6.2000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.T., et al. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395:689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite A.R., Fisman D.N. Reporting, epidemic growth, and reproduction numbers for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) epidemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S., et al. An interim review of the epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus. Epidemiol. Health. 2020;42:e2020006. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai, N. et al (2020). Report 3: Transmissibility of 2019-nCoV. WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling, MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, J-IDEA, Imperial College London, UK. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-2019-nCoV-transmissibility.pdf (accessed 9 February 2020).

- Backer J.A., et al. 2020Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20–28 January 2020. Euro Surveill. 25 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., et al. 2020Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehl S., et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in returning travelers from Wuhan, China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P., et al. A familial cluster of infection associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating potential person-to-person transmission during the incubation period. J. Infect. Dis. 2020:jiaa077. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., et al. Asymptomatic cases in a family cluster with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To K.K., et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386–389. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., et al. Isolation of 2019-nCoV from a stool specimen of a laboratory-confirmed case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:123–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) — China, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S.Y., et al. Evolving status of the 2019 novel coronavirus infection: proposal of conventional serologic assays for disease diagnosis and infection monitoring. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus Disease (2019) (COVID-19): CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cdna-song-novel-coronavirus.htm (accessed 26 February 2020).

- World Health Organization (2020) Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected: Interim Guidance 28 January 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected

- World Health Organization (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation report 49. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200309-sitrep-49-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=70dabe61_4

- Quilty B.J., et al. 2020Effectiveness of airport screening at detecting travellers infected with novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Euro Surveill. 25 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S. et al (2020) Relative sensitivity of international surveillance, WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling, MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics (J-IDEA), Imperial College, London. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College---COVID-19---Relative-Sensitivity-International-Cases.pdf (accessed 24 February 2020).

- Menachery V.D., et al. A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1508–1513. doi: 10.1038/nm.3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]