Abstract

In this study, we amplified and sequenced the first genome of porcine torovirus (PToV SH1 strain). The genome was found to be 28,301 bp in length, sharing 79 % identity with Breda virus. It mainly consists of replicase (20,906 bp) and structural genes: spike (4,722 bp), membrane (702 bp), hemagglutinin-esterase (1,284 bp), and nucleocapsid (492 bp). Sequence alignments and structure prediction suggest genetic differences among toroviruses, mainly in NSP1 (papain-like cysteine proteinase domain). Rooted phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the 3C-like proteinase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase genes. PToV, Berne virus and Breda virus were clustered together, forming a separate branch from white bream virus that was distant from that of the coronaviruses.

Keywords: Porcine torovirus, Genome, China, Comparative analysis

Introduction

Toroviruses, potential intestinal pathogens that can infect horses, calves, humans, pigs and other animals, belong to the subfamily Torovirinae within the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales (ICTV, http://ictvonline.org/virusTaxonomy.asp). The first identified torovirus was isolated from a horse with diarrhea (equine torovirus, EToV, also called Berne virus) in 1972 [23, 27, 29]. A few years later, torovirus was also found in American calves with diarrhea (bovine torovirus, BToV, also called Breda virus) [29] and in humans with gastroenteritis (human torovirus, HToV) [2, 14, 15]. The presence of torovirus in swine fecal specimens was also verified, but there has not been a report of obvious clinical symptoms or economic losses [16–20, 22].

Toroviruses are an enveloped viruses with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of about 25-30 kb in length, sharing a similar genomic organization with coronavirus [5, 7, 28]. The genome contains two open reading frames connected by a frameshift site to express a replicase polyprotein ORF1ab (PP1ab), and four open reading frames encoding structural proteins: spike (S), membrane (M), hemagglutinin-esterase (HE) and nucleocapsid (N) [11–13, 30].

Epidemiological surveys have shown that porcine torovirus (PToV) has been distributed worldwide and is prevalent in Africa, Europe and Asia [16–20, 22]. However, research on this virus has been limited, which is partly because of insufficient information as well as a lack of an available in vitro system for conducting further studies. Limited genomic information has also restricted our understanding of the virus.

In this study, we completed the full-length sequencing of the PToV genome based on the genome of the Breda1 virus. All information regarding PToV genomic RNA may be further analyzed to explain the different pathogenicities of toroviruses in horses, calves, humans and pigs.

Materials and methods

A PToV-positive stool specimen was collected from a commercial piggery in Shanghai. The sample was diluted 1:1 (v/v) with PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.2-7.4), homogenized by vortexing, and clarified by centrifuging at 5,000×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The sample was confirmed to contain only one strain of PToV (PToV SH1 strain) by reverse transcription (RT) PCR and sequencing.

RNA was extracted from 300 μl of the fecal specimen supernatant with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA was dissolved in 25 μl RNase-free dH2O. The RT reaction was performed using a PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). Briefly, purified viral RNA 16 μl was mixed with 4 μl of PrimeScript® RT Master Mix to a total volume of 20 μl. The reaction mixture was heated to 42 °C for 5 min, chilled on ice and then incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C followed by 5 s at 85 °C to inactivate the reverse transcriptase enzyme.

Primer 5.0 was used for primer design (synthesized by Sangon, Shanghai, China). Seventeen pairs of primers were designed based on Breda1 virus and the most similar PToV sequences for obtaining the majority of the PToV genome. Full-length genome synthesis was achieved by using six additional pairs of primers from sequenced fragments.

PCR was performed using 2 μl of cDNA and a master mix containing 5 μl 10× LA PCR buffer, 2 μl of each primer (20 μm), 8 μl dNTP mixture (2.5 mM each), 0.5 μl LA Taq (Takara, Dalian, China), and 30.5 μl of ddH2O in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. The mixture was denatured at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 50 °C and 2 min at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. There were minor modifications to the cycling conditions depending on the primers and the length of the products.

PCR products were extracted from an agarose gel using an AxyPrep™ DNA Gel Extraction Kit. Purified PCR products were then ligated into a PMD-18T vector (Takara, Dalian, China). For each product, three to five positive colonies were selected and sequenced. Several purified products with much longer nucleotide sequences were sequenced directly using PCR primers.

Polyprotein ORF1ab (pp1ab) was compared with the sequence databases using HMMER [8] and HHpred [3, 10]. MUSCLE [6] was used for producing alignments of nidovirus proteins. Alignments were prepared in publication quality with Jalview [26]. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using the WAG model by MUSCLE alignments employing MEGA.v5.05 software [24]. Antigen analysis was performed using Protean in DNAStar [4]. The program KnoTInFrame was used for prediction of ribosomal frameshifts and slippery sequences [25]. The pseudoknot structure was viewed using pknotsRG [21].

Results

The complete genome of the PToV SH1 strain was composed of 28,301 bp, with a GC content of 35.02 %, while that of Breda virus was 28,475 bp in length and had a GC content of 38.01 %. Both the PToV and Breda virus genomes were AT rich. Pp1ab was encoded from nt 790 to 20,906, with a length of 20,117 bp (6,705 aa). ORF1a started at nt 790 and ended at nt 14,043, encoding a 4,417-aa replicase. The lengths of structural genes S, M, HE, and N were 4722 bp, 702 bp, 1284 bp, and 492 bp, respectively. In comparing the 5′ UTR of Breda virus (858 bp) with that of PToV (789 bp), the latter was observed to have a 70-bp deletion in the middle region. On the other hand, a 39-bp sequence inserted at the end of the 5’UTR was seen in PToV compared with Berne virus (821 bp).

The genome sequence has been deposited in GenBank and is named porcine torovirus SH1 strain. The accession number is JQ860350.

The PToV genome shared 79 % identity with the Breda virus strain Breda1. Alignments of torovirus sequences revealed that PToV pp1ab has 14.3 % divergence from Breda virus, 22.8 % divergence from Berne virus, and more than 75 % divergence from white bream virus, coronaviruses and arteriviruses.

Among PToVs, structural proteins of SH1 strain were more similar to Korean strains than European strains. S shared 99 % amino acid sequence identity with Korean strain 07-56-22 and 95.7 % with European strain Markelo. HE shared 77.1-93.8 % amino acid sequence identity with European strains and 77.6-96.3 % with Korean strains. N shared 90.6-93.1 % amino acid sequence identity with Korean strains. M was more conserved, sharing 98 % amino acid sequence identity with the reported PToVs.

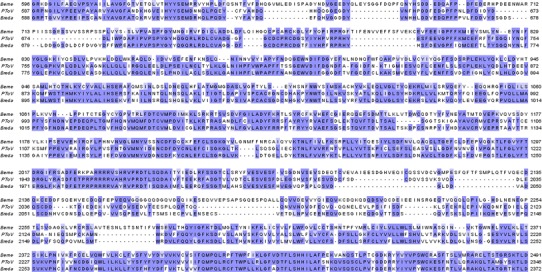

Amino acid variation among toroviruses was mainly found in NSP1 (papain-like proteinase domain), where amino acid deletions and mutations occur frequently. In comparison with Berne virus, PToV and BToV NSP1 were commonly missing 2, 11, 12, 6, 1, 5, 16, 4, 12, 15, 14, 7, 14 and 1 amino acids at positions 633, 640, 650, 673, 704, 706, 727, 1156, 2020, 2032, 2071, 2100, 2138 and 2216, respectively, and had insertions of 2, 1, 2, 3, 3, 2, 3, 1 and 3 amino acids at positions 664, 678, 747, 797, 918, 977, 998, 2113 and 2209, respectively. PToV NSP1 was missing 6, 1, 1, 6, 4, 6, 1 and 1 additional amino acids at positions 673, 830, 836, 1080, 2040, 2071, 2084 and 2126, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

NSP1 sequence alignment of PToV (JQ860350), Breda virus (AY427798) and Berne virus (DQ310701)

Conserved domains of the 3C-like serine protease (3CLpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) were predicted from sequence alignments employing HMMER, Pfam, and MUSCLE and structure prediction using HHpred with PSI-BLAST. PToV 3CLpro was 287 aa in length, the same length with that of Breda virus, and 5 aa shorter than that of Berne virus [17]. The length of RdRp in PToV was 1,019 aa, which was longer than those of Breda virus (1,012 aa) and Berne virus (1,010 aa).

There is a slippery sequence and an RNA pseudoknot at position 14,031, where a ribosome frameshift occurs and forms a fusion protein, ORF1ab. The PToV heptanucleotide slippery sequence, UUUAAAC (nt 14,031-14,037), is identical to those of BToV and EToV [6].

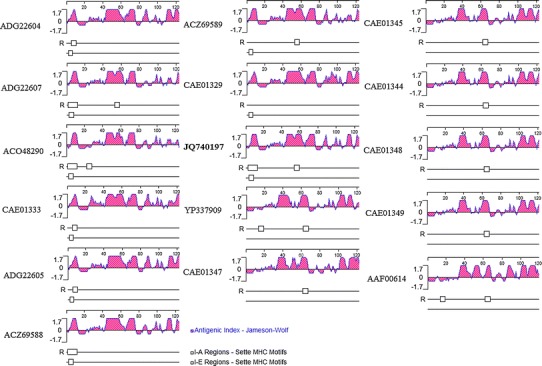

The PToV HE was 10 aa longer than those of Breda virus and HToV. In antigenicity analysis, these 10 amino acids formed an antigen site and a specific I-E region of an MHC motif at position 6 (Fig. 2). In contrast to Breda virus and Berne virus, PToV S contained three discontinuous deletions, with the sizes of 3, 1 and 4 amino acids at position 195, 240 and 679, respectively. There is also a 2-aa insertion at position 743. Whether the amino acid deletions and insertions in PToV are associated with its low virulence needs to be evaluated in future studies [1, 9].

Fig. 2.

Hemagglutinin-esterase antigenicity analysis of porcine torovirus (ADG22604, ADG22607, ACO48290, CAE01333, ADG22605, ACZ69588, ACZ69589, CAE01329 and JQ640197), bovine torovirus (YP337909, CAE01347, CAE01344, CAE01345, CAE01348, CAE01349) and human torovirus (AAF00614) using DNAStar Protean software. The PToV SH1 strain accession number is in bold

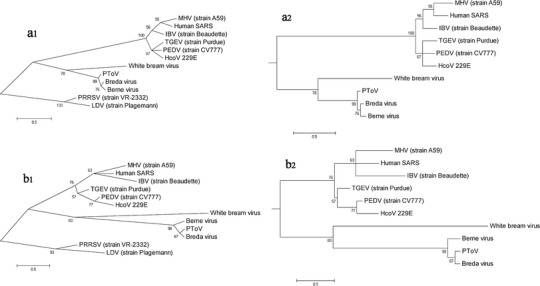

To infer the direction of torovirus evolution among toroviruses in the family Coronaviridae, phylogenetic trees were constructed using the domains 3CLpro and RdRp, which are conserved in members of the order Nidovirales. Arteriviruses were used as an outgroup to root the trees.

Despite similar topologies in the two trees, there were somewhat incongruent phylogenies (Fig. 3). For the 3CLpro tree, PToV was clustered with Breda virus, forming a separate branch with Berne virus. For the RdRp tree, the phylogenies were represented more closely within groups. In the torovirus group, PToV formed a branch with Breda virus and Berne virus, separate from white bream virus. However, both trees showed that PToV was more distantly related to Berne virus than to Breda virus.

Fig. 3.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree constructed using MEGA 5.02 software with the WAG model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates, representing the genetic relationships within the order Nidovirales. RefSeq accession numbers referred to in the trees are as follows: NC_001846 (MHV, strain A59), NC_002645 (HcoV 229E), NC_004718 (human SARS virus), NC_008516 (white bream virus), NC_007447 (Breda virus), AF353511 (PEDV, strain CV777), DQ310701 (Berne virus), Z34093 (TGEV, strain Purdue), M94356 (IBV, strain Beaudette), U15146 (LDV, strain Plagemann), U87392 (PRRSV, strain VR-2332). a1, unrooted RdRp tree; a2, rooted RdRp tree; b1, unrooted 3CLpro tree; b2, rooted 3CLpro tree

Discussion

Although there have been reports on torovirus infection in horses, calves, pigs and humans, evidence of pathogenicity was mainly focused on BToV, EToV and HToV. There is no evidence that PToV causes diarrhea [1, 16–20, 22].

The main difference in the non-structural genes among toroviruses was found in replicase ORF1a, where bases were lost or replaced frequently. This variation hampered our efforts to amplify the segment. Compared with Breda and Berne virus, PToV SH1 strain pp1ab lacked 28 and 152 amino acids, respectively and had numerous amino acid substitutions, which could possibly result in functional changes in some domains and adaption to the host.

Our primers, specific for non-structural genes, were designed based on Breda1 virus. The genome is highly similar except for the first 26 nucleotides of the 5′UTR and the last 22 nucleotides of the 3′UTR. The 5′UTR and 3′UTR were obtained easily and are conserved, giving us confidence that most of the bases in the primers are correct.

The HE protein is located on the surface of the virion. Antibodies against the HE protein can neutralize the virus. The inserted 9-10 amino acids in PToV HE formed an antigen site and a specific I-E region of the MHC motif, which is a characteristic of porcine torovirus only. The spike protein is responsible for the antigenic properties of the virus and contains the binding site for the cell-surface receptor. As the values of the antigen index did not show obvious divergence in comparison with Breda virus and Berne virus, the discontinuous deletions and insertions in the PToV spike protein might be the result of host specificity or low virulence. However, this hypothesis needs to be studied further with more evidence from genomic information and experimental data.

Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that there is a rather large evolutionary distance between toroviruses and arteriviruses and coronaviruses. Rooted RdRp phylogenic tree analysis revealed that toroviruses were closer to the outgroup node. However, in the 3CLpro tree analysis, the torovirus group was farther away from the outgroup. The topologies of toroviruses were also somewhat different. Nonetheless, the evolutionary distance among Berne virus, PToV and Breda virus was similar. On the other hand, the length of 3Clpro and RdRp proteins varied frequently in toroviruses. The changes were in accordance with the phylogenies.

In conclusion, PToV SH1 genome sequencing not only provides more information on porcine torovirus but also contributes to a better understanding of toroviruses at the molecular level. The genome sequence, combined with the BToV genome and partial EToV genome sequence, is expected to facilitate further research on virus antigenicity, virulence, infection, and replication in animals.

References

- 1.Aita T, Kuwabara M, Murayama K, Sasagawa Y, Yabe S, Higuchi R, Tamura T, Miyazaki A, Tsunemitsu H. Characterization of epidemic diarrhea outbreaks associated with bovine torovirus in adult cows. Arch Virol. 2012;157:423–431. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beards GM, Hall C, Green J, Flewett TH, Lamouliatte F, Du Pasquier P. An enveloped virus in stools of children and adults with gastroenteritis that resembles the Breda virus of calves. Lancet. 1984;1:1050–1052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91454-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biegert A, Mayer C, Remmert M, Soding J, Lupas AN. The MPI bioinformatics toolkit for protein sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W335–W339. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burland TG. DNASTAR’s Lasergene sequence analysis software. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:11. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Draker R, Roper RL, Petric M, Tellier R. The complete sequence of the bovine torovirus genome. Virus Res. 2006;115:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagerland JA, Pohlenz JF, Woode GN. A morphological study of the replication of Breda virus (proposed family Toroviridae) in bovine intestinal cells. J Gen Virol. 1986;67(Pt 7):1293–1304. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher T, Buchmeier M. Coronavirus spike proteins in viral entry and pathogenesis. Virology. 2001;279:371–374. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrand A, Remmert M, Biegert A, Söding J. Fast and accurate automatic structure prediction with HHpred. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2009;77:128–132. doi: 10.1002/prot.22499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horzinek MC, Ederveen J, Weiss M. The nucleocapsid of Berne virus. J Gen Virol. 1985;66(Pt 6):1287–1296. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-6-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horzinek MC, Ederveen J, Kaeffer B, de Boer D, Weiss M. The peplomers of Berne virus. J Gen Virol. 1986;67(Pt 11):2475–2483. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-11-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koopmans M, Ederveen J, Woode GN, Horzinek MC. Surface proteins of Breda virus. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:1896–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koopmans MP, Goosen ES, Lima AA, McAuliffe IT, Nataro JP, Barrett LJ, Glass RI, Guerrant RL. Association of torovirus with acute and persistent diarrhea in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:504–507. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnan T, Naik TN. Electronmicroscopic evidence of torovirus like particles in children with diarrhoea. Indian J Med Res. 1997;105:108–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroneman A, Cornelissen LA, Horzinek MC, de Groot RJ, Egberink HF. Identification and characterization of a porcine torovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:3507–3511. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3507-3511.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matiz K, Kecskemeti S, Kiss I, Adam Z, Tanyi J, Nagy B. Torovirus detection in faecal specimens of calves and pigs in Hungary: short communication. Acta Vet Hung. 2002;50:293–296. doi: 10.1556/AVet.50.2002.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pignatelli J, Jimenez M, Luque J, Rejas MT, Lavazza A, Rodriguez D. Molecular characterization of a new PToV strain. Evolutionary implications. Virus Res. 2009;143:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pignatelli J, Grau-Roma L, Jimenez M, Segales J, Rodriguez D. Longitudinal serological and virological study on porcine torovirus (PToV) in piglets from Spanish farms. Vet Microbiol. 2010;146:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pignatelli J, Jimenez M, Grau-Roma L, Rodriguez D. Detection of porcine torovirus by real time RT-PCR in piglets from a Spanish farm. J Virol Methods. 2010;163:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeder J, Giegerich R. Design, implementation and evaluation of a practical pseudoknot folding algorithm based on thermodynamics. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin D-J, Park S-I, Jeong Y-J, Hosmillo M, Kim H-H, Kim H-J, Kwon H-J, Kang M-I, Park S-J, Cho K-O. Detection and molecular characterization of porcine toroviruses in Korea. Arch Virol. 2010;155:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0595-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snijder EJ, Horzinek MC. Toroviruses replication, evolution and comparison with other members of the coronavirus-like superfamily. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2305–2316. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-11-2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theis C, Reeder J, Giegerich R. KnotInFrame: prediction of -1 ribosomal frameshift events. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6013–6020. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss M, Steck F, Horzinek MC. Purification and partial characterization of a new enveloped RNA virus (Berne virus) J Gen Virol. 1983;64(Pt 9):1849–1858. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-9-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss M, Horzinek MC. Morphogenesis of Berne virus (proposed family Toroviridae) J Gen Virol. 1986;67(Pt 7):1305–1314. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woode GN, Reed DE, Runnels PL, Herrig MA, Hill HT. Studies with an unclassified virus isolated from diarrheic calves. Vet Microbiol. 1982;7:221–240. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(82)90036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanoni R, Weiss M, Peterhans E. The haemagglutinating activity of Berne virus. J Gen Virol. 1986;67(Pt 11):2485–2488. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-11-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]