Abstract

This study presents the pathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular findings associated with the extra-intestinal detection of canine kobuvirus (CaKV) in a 5-month-old Chihuahua puppy, that had a clinical history of bloody-tinged feces. Principal pathological findings were interstitial pneumonia, necrotizing bronchitis, and parvovirus-induced enteritis. Molecular diagnostic methods identified CaKV within the cerebellum, cerebrum, lung, tonsil, and liver. CaKV and rotavirus were not identified within the feces and intestine. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays detected antigens of CDV and CAdV-1 in the lungs. These results confirmed the extra-intestinal detection of CaKV in this puppy and represent the first extra-intestinal detection of CaKV in a dog.

Keywords: Fecal Sample, Interstitial Pneumonia, Giardiasis, Canine Distemper Virus, RdRp Gene

Kobuviruses are officially classified into three species, Aichivirus A (human kobuvirus), Aichivirus B (bovine kobuvirus), and Aichivirus C (porcine kobuvirus) [15]. The viral genome encodes a leader (L) protein, as well as a structural polyprotein (VP0, VP3, and VP1) and non-structural (2A-2C and 3A-3D) proteins [25]. The 3D segment of the kobuvirus genome is a conserved region, and the VP1 protein is the most variable, similar to other picornaviruses [21, 26].

Kobuviruses were identified in fecal samples from diarrheic and asymptomatic humans as well as in several animals. In Brazil, kobuviruses were initially detected in the fecal samples of pigs and sheep, and viral RNA was identified in the serum of pigs between 3 and 180 days-of-age [2]. Thereafter, the presence of Aichivirus B and C was identified in fecal samples of cattle [23] and pigs [22], respectively.

Canine kobuvirus (CaKV) was first described in fecal samples of dogs with gastroenteritis in the USA in 2011 [16], with subsequent reports in the UK [3], Italy [4], Korea [19], and China [17]. CaKV is frequently identified within fecal samples of animals with or without clinical signs of diarrhea [4]. There are few descriptions of coinfection due to CaKV and other viral agents: a recent study identified CaKV in association with a several agents including canine herpesvirus type 1 (CaHV-1), canine distemper virus (CDV), canine parvovirus (CPV), and canine adenovirus A types 1 (CAdV-1) and 2 (CAdV-2) in diarrheic and non-diarrheic dogs from Korea [19]. However, none of these studies have identified CaKV in the tissues of dogs. Consequently, the current study describes the first occurrence of CaKV in multiple tissues of a puppy from Southern Brazil, which was also coinfected with other infectious disease agents.

In early March, 2015, an outbreak of diarrhea occurred at a kennel in the city of Colorado, Paraná State, Southern Brazil. The owner reported that seven 50-60-day-old Chihuahua puppies developed diarrhea, anorexia, and apathy with death occurring between 12-20 days after the onset of clinical manifestations. A necropsy on one of these puppies, done elsewhere, revealed interstitial pneumonia and necrotizing hepatitis associated with intranuclear inclusion bodies in hepatocytes, and a diagnosis of infectious canine hepatitis was established.

In late July, 2015, the carcass of a 5-month-old puppy with a clinical history of abdominal pain, anorexia, and blood-tinged feces was submitted for routine necropsy. This puppy had received two doses of a commercial vaccine that contained eight immunogens (CDV, CPV-2, canine parainfluenza virus, canine adenovirus 1 and 2, canine coronavirus, and Leptospira canicola and grippotyphosa serovars.); the last dose being six weeks before spontaneous death. Several tissue fragments (liver, spleen, lung, cerebellum, cerebrum, mesenteric lymph node, kidney, heart, and intestine) were collected and routinely processed for histopathological evaluation. Selected formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue fragments of the liver and lung were used in immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays designed to detect the N protein of CDV (VMARD, Washington, USA), and with a commercial monoclonal antibody designed to identify CAdV-1 and CAdV-2 (VMARD, Washington, USA), using a previously described procedure [8]. Positive controls consisted of FFPE tissues from previous studies [9]; negative controls consisted of the diluents of the primary antibodies. Duplicates of the tissues cited above, as well as feces, were collected for parasitological and virological evaluations.

For virological investigation the tissues were processed using the MagNaLyser Instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and the fecal samples were submitted to nucleic acid extraction as described elsewhere [1]. The nucleic acid was eluted in 50 µl of ultrapure RNAse-free DEPC-treated sterile water. Negative (sterile water) and positive controls, consisting of viral nucleic acids (CAdV-1, CAdV-2, CDV, and CaHV-1) from previous cases [11, 12], as well as CPV2 commercial vaccine, were included in all nucleic acid extraction procedures.

The extracted nucleic acids were used in RT-PCR/PCR assays designed to amplify specific genes from viral agents known to infect dogs, including the: CDV N gene [5], CaHV-1 glycoprotein B gene [24], CPV VP2 gene [13], and the E gene of CAdV-1 and 2 [14].

The RT-PCR assay to detect CaKV is designed to amplify a 216 bp region of the RdRp gene [20]. The partial region of the VP1 protein CaKV was amplified by using the primer pairs VP1-DogF (5’-CAAHCTKGARAACTTCTTCTC-3’) and VP1-DogR (5’-GAAGTTKGAGAGCATCTGKC-3’), which were designed using the complete sequences of human, canine, and feline kobuvirus available in GenBank.

The intestine and the fecal samples were used in RT-PCR assays designed to identify rotavirus species A, B, and C [18]. All RT-PCR and PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel in TBE buffer, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light.

Two RT-PCR products of the RdRp gene and the VP1 region of CaKV were purified using the GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare), quantified in a Qubit® Fluorometer (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and sequenced in an ABI3500 Genetic Analyzer sequencer with the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit using the forward and reverse primers used in the RT-PCR assay (Applied Biosystems). The phylogenetic tree and the nt identity matrix were developed using the MEGA 6.0 and BioEdit 7.2.5, respectively. The analyses were based on the neighbor-joining method and the Kimura 2-parameter model. Bootstrapping was statistically supported with 1,000 replicates. The referenced sequences included in this study were acquired from GenBank.

The most remarkable pathological alterations were observed in the lungs and consisted of discrete necrosis of bronchiolar and bronchial epithelial cells associated with small basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies within some of these cells, severe diffused interstitial pneumonia, in addition to pulmonary congestion and edema. The intestinal lesions were suggestive of parvovirus enteritis. Other significant pathological findings included necrotizing myocarditis and lymphoid depletion of the spleen and tonsils.

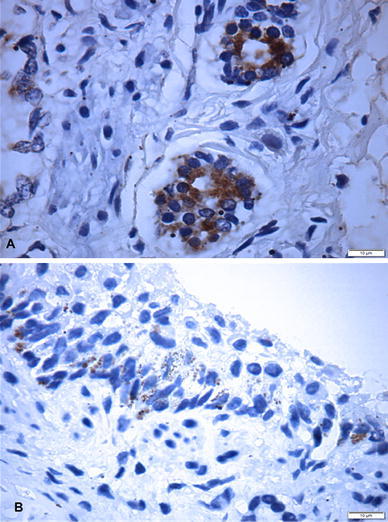

Immunohistochemistry revealed the detection of the antigens of CDV within the bronchiole and bronchiolar epithelium (Fig. 1A) and antigens of CAdV-1 within the cytoplasm of endothelial cells (Fig.1B); antigens of CAdV-1 and -2, and CDV were not identified in the liver. Examples of Giardia spp. were identified by the floating technique from the fecal sample of the puppy.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical demonstration of antigens of canine adenovirus-1 (A) and canine distemper virus (B) in the lung of a puppy infected with canine kobuvirus. Immunoperoxidase; Bar=10 µm

The distribution of the viral nucleic acids identified within multiple tissues and the feces of the puppy are given in Table 1. Specific fragments of the genes of CDV, CaKV, CPV-2, and CaHV-1 were amplified from multiple tissues. Mixed infections associated with CaKV were identified in the cerebrum, lung, and tonsils. In addition, nucleic acid from CPV-2 was identified within fragments of the small intestine and a single infection associated with CaKV was also detected in the cerebellum and liver. Further, the fecal sample of the puppy contained CPV-2 DNA. The nucleic acids of all other viral agents evaluated, including rotavirus species A, B, and C, were not amplified.

Table 1.

Detection of viral nucleic acids amplified from multiple tissues and the feces of a diarrheic dog

| Tissues | Viral agents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDV | CPV-2 | CaHV-1 | CAdV-1 | CAdV-2 | CaKV | RV | |

| Cerebrum | + | - | - | - | - | + | n.d.* |

| Cerebellum | - | - | - | - | - | + | n.d. |

| Lung | + | - | - | - | - | + | n.d. |

| Tonsil | - | - | + | - | - | + | n.d. |

| Kidney | - | - | + | - | - | - | n.d. |

| Liver | - | - | - | - | - | + | n.d. |

| Small intestine | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Feces | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

n.d.: not done

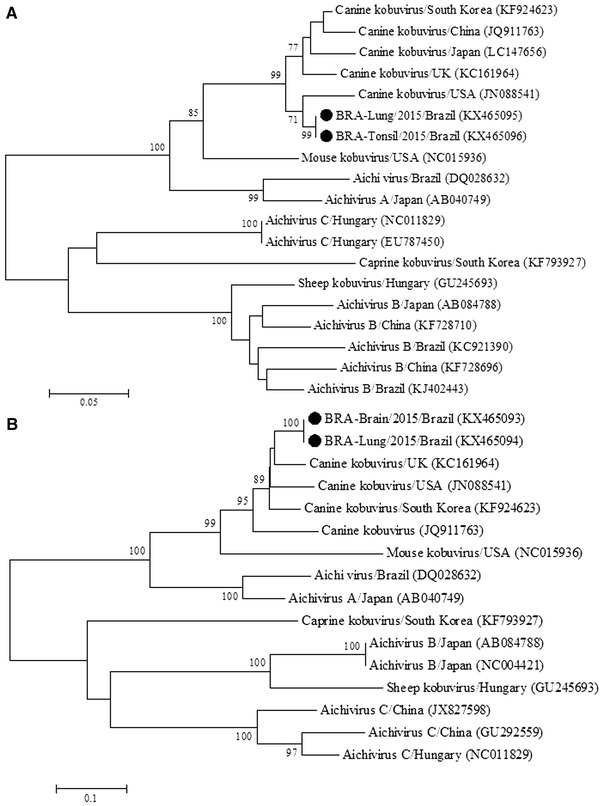

The partial sequences of CaKV VP1 and RdRp genes identified in this study have been deposited in GenBank (Accession numbers: VP1: brain KX465093, lung KX465094; RdRp: lung, KX465095; tonsil KX465096). The phylogenetic analysis of the RdRp region (nt 201) showed that the CaKV strains from the lung and tonsil of this dog grouped with other strains of CaKV previously described (Fig. 2A), and they exhibited higher nt sequence identity (95 to 96%) with canine than with mouse (88%) and human (80 to 83%) kobuvirus strains.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of a partial nucleotide sequence (nt 201) of the RdRp gene (a) and partial region of the VP1 protein (nt 303) of canine kobuvirus (CaKV) (b). The strains of CaKV identified during this study are marked with a filled circle

Moreover, the phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 region (nt 303) revealed that the CaKV strains identified in the lung and cerebrum of this dog clustered with other strains of CaKV and mouse kobuvirus. In addition, no phylogenetic difference was observed between strains of Aichivirus A, since those derived from dogs, mouse, and humans, clustered within the same group (Fig. 2B). Further, the VP1 CaKV strains from the present study showed 85.2~92%, 91.5~100%, 71% nt identity; and 73.6%, 65.6~67.6%, and 62.1% amino acid similarity with dog, mouse, and human kobuvirus strains, respectively.

The unique finding of this investigation was the amplification of the nucleic acid of CaKV from multiple tissues of this puppy, using two RT-PCR assays. These results contrast with previous descriptions of CaKV, where nucleic acids were detected exclusively in the feces of diarrheic dogs [4, 16, 19]; however, these studies did not evaluate the presence of CaKV in tissues. Surprisingly, CaKV was not detected in the feces or the intestinal fragment of this puppy using the RT-PCR assay applied during this study. Alternatively, a more sensitive assay might be required to detect this virus when there is concomitant infection with other severe intestinal diseases, such as those associated with CPV-2 and Giardia spp. Nevertheless, these findings confirm the detection of CaKV in this dog, and represent the first description of canine kobuvirus in Brazil.

It must be highlighted that coinfections of CaKV with other viral agents were identified in several tissues/organs, including the cerebrum, lung, and the tonsils (Table 1); and there was concomitant parvovirus enteritis and giardiasis. Mixed infections in dogs have been previously related with descriptions of simultaneous viral, bacterial, and parasitic agents [10, 11], as well as mixed infections with multiple viral agents [12].

Coinfections with CaKV and other infectious agents in dogs, as observed in this investigation, have been described in diarrheic outbreaks [19], although the pathogenic effect of CaKV is unclear. Interestingly, we have identified CaKV with concomitant infections related to CDV (by RT-PCR and IHC) and CAdV-1 (only by IHC) in the lung of this dog and associated with necrotizing bronchiolitis, interstitial pneumonia, as well as pulmonary congestion and edema. Interstitial pneumonia is a typical pulmonary manifestation of infection due to CDV and CAdV-1 [11, 12]. CDV produces interstitial pneumonia due to the viral tropism for epithelial cells of the pulmonary alveoli, while CAdV induces the same lesions due to alteration of the integrity of the vascular endothelium of the alveolar wall [7]. However, interstitial pneumonia was also described in pigs experimentally infected with porcine kobuvirus [27], so it is possible that CaKV could have been associated with the pulmonary infection observed in this dog.

Additionally, the presence of kobuvirus is frequently associated with an initial infection induced by other infectious agents. In this case, there were concomitant coinfections caused by CPV-2 and CDV; these are well known immunosuppressive infectious pathogens [6] that facilitate the entry and colonization of secondary agents. Therefore, we believe that the multiple coinfections observed in this puppy might be related to the immunosuppression induced by CDV and CPV-2, and worsened with the concomitant giardiasis.

Furthermore, widespread viral dissemination was demonstrated in multiple tissues as CaKV nucleic acids were detected in the liver, lung, brain, and tonsils of this puppy. These findings complement a previous investigation by our group, where kobuvirus was identified in the sera of pigs of various ages with and without clinical signs of diarrhea [2]. The phylogenetic analysis of the conserved RdRp region of the CaKV described in this study revealed higher nt sequence identity between canine (95%-96%), mouse (88%), and human (80%-83%) kobuvirus strains. The sequence analysis of the VP1 protein, considered the most variable protein in this virus, obtained from the brain and pulmonary fragments were identical to each other and had 85.2~92%, 91.5~100%, 71% nt identity; and 73.6%, 65.6~67.6%, and 62.1% amino acid similarity with dog, mouse, and human kobuviruses, respectively. Moreover, these strains of kobuvirus grouped within the same cluster during phylogenetic evaluation.

In conclusion, CaKV genomes were identified in multiple tissues from a puppy that was coinfected with other viral and parasitic agents, confirming the systemic distribution of kobuvirus in this puppy. Although the role of CaKV in the etiopathogenesis of disease is obscure, there is evidence that pathological alterations might have occurred. Finally, the phylogenetic analysis confirmed that the strains of CaKV identified during this investigation are similar to those described in other geographical locations. These findings represent the first characterization of CaKV in the tissues of a puppy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the following Brazilian institutes: CNPq – grant number 305062/2015-8), CAPES and FINEP. S.A. Headley, A.F. Alfieri, A.A. Alfieri, and E. Lorenzetti are recipients of CNPq and Araucaria Foundation (FAP/PR) fellowships, respectively.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Supervision of the ethical committee to conduct this study was not required because this work was conducted with organ fragments of an animal that died spontaneously and was submitted for routine diagnosis by the owner. All applicable international, and national guidelines for the care and use of animals was followed.

Footnotes

J. Ribeiro and S. A. Headley contributed equally towards the development of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Alfieri AA, Parazzi ME, Takiuchi E, Medici KC, Alfieri AF. Frequency of group A rotavirus in diarrhoeic calves in Brazilian cattle herds, 1998-2002. Tropic Animal Health Product. 2006;38:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s11250-006-4349-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry AF, Ribeiro J, Alfieri AF, van der Poel WH, Alfieri AA. First detection of kobuvirus in farm animals in Brazil and the Netherlands. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1811–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmona-Vicente N, Buesa J, Brown PA, Merga JY, Darby AC, Stavisky J, Sadler L, Gaskell RM, Dawson S, Radford AD. Phylogeny and prevalence of kobuviruses in dogs and cats in the UK. Veter Microbiol. 2013;164:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Martino B, Di Felice E, Ceci C, Di Profio F, Marsilio F. Canine kobuviruses in diarrhoeic dogs in Italy. Veter Microbiol. 2013;166:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frisk AL, Konig M, Moritz A, Baumgartner W. Detection of canine distemper virus nucleoprotein RNA by reverse transcription-PCR using serum, whole blood, and cerebrospinal fluid from dogs with distemper. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3634–3643. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3634-3643.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene CE, Decaro N. Canine viral enteritis. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Saint Louis: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene CE, Vandevelde M. Canine distemper. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. St Louis: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Headley SA, Soares IC, Graca DL. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-immunoreactive astrocytes in dogs infected with canine distemper virus. J Comp Pathol. 2001;125:90–97. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headley SA, Amude AM, Alfieri AF, Bracarense AP, Alfieri AA, Summers BA. Molecular detection of Canine distemper virus and the immunohistochemical characterization of the neurologic lesions in naturally occurring old dog encephalitis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21:588–597. doi: 10.1177/104063870902100502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Headley SA, Shirota K, Baba T, Ikeda T, Sukura A. Diagnostic exercise: Tyzzer’s disease, distemper, and coccidiosis in a pup. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:151–154. doi: 10.1354/vp.46-1-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Headley SA, Alfieri AA, Fritzen JTT, Garcia JL, Weissenböck H, da Silva AP, Bodnar L, Okano W, Alfieri AF. Concomitant canine distemper, infectious canine hepatitis, canine parvoviral enteritis, canine infectious tracheobronchitis, and toxoplasmosis in a puppy. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2013;25:129–135. doi: 10.1177/1040638712471344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Headley SA, Bodnar L, Silva AP, Alfieri AF, Gomes LA, Okano W, Alfieri AA. Canine distemper virus with concomitant infections due to canine herpesvirus-1, canine parvovirus, and canine adenovirus in puppies from Ssouthern Brazil. Jacobs J Microbiol Pathol. 2015;1:015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong C, Decaro N, Desario C, Tanner P, Pardo MC, Sanchez S, Buonavoglia C, Saliki JT. Occurrence of canine parvovirus type 2c in the United States. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007;19:535–539. doi: 10.1177/104063870701900512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu RL, Huang G, Qiu W, Zhong ZH, Xia XZ, Yin Z. Detection and differentiation of CAV-1 and CAV-2 by polymerase chain reaction. Vet Res Commun. 2001;25:77–84. doi: 10.1023/A:1006417203856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ICTV (2016) International Comittee on Taxonomy of Viruses http://www.ictvonlineorg/virusTaxonomyasp. Accessed 14 April 2016

- 16.Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Dubovi EJ, Qaisar N, Henriquez JA, Medina J, Shields S, Lipkin WI. Characterization of a canine homolog of human Aichivirus. J Virol. 2011;85:11520–11525. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05317-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, Wei S, Guo D, Wang Z, Geng Y, Wang E, Zhao X, Su M, Wang X, Sun D. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of canine kobuviruses in diarrhoetic dogs in northeast China. J Vet Med Sci. 2016;78:7–11. doi: 10.1292/jvms.15-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Médici KC, Barry AF, Alfieri FA, Alfieri AA. Porcine rotavirus groups A, B, and C identified by polymerase chain reaction in a fecal sample collection with inconclusive results by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Swine Health Produc. 2011;19:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oem JK, Choi JW, Lee MH, Lee KK, Choi KS. Canine kobuvirus infections in Korean dogs. Arch Virol. 2014;159:2751–2755. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reuter G, Boldizsar A, Pankovics P. Complete nucleotide and amino acid sequences and genetic organization of porcine kobuvirus, a member of a new species in the genus Kobuvirus, family Picornaviridae. Arch Virol. 2009;154:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuter G, Boros A, Pankovics P. Kobuviruses - a comprehensive review. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:32–41. doi: 10.1002/rmv.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro J, de Arruda Leme R, Alfieri AF, Alfieri AA. High frequency of Aichivirus C (porcine kobuvirus) infection in piglets from different geographic regions of Brazil. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2013;45:1757–1762. doi: 10.1007/s11250-013-0428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro J, Lorenzetti E, Alfieri AF, Alfieri AA. Kobuvirus (Aichivirus B) infection in Brazilian cattle herds. Vet Res Commun. 2014;38:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s11259-014-9600-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronsse V, Verstegen J, Thiry E, Onclin K, Aeberle C, Brunet S, Poulet H. Canine herpesvirus-1 (CHV-1): clinical, serological and virological patterns in breeding colonies. Theriogenology. 2005;64:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Tsuzuki H, Suzuki Y, Ishikawa N, Takeda N, Miyamura T, Yamazaki S. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of Aichi virus, a distinct member of the Picornaviridae associated with acute gastroenteritis in humans. J Virol. 1998;72:8408–8412. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8408-8412.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita T, Ito M, Kabashima Y, Tsuzuki H, Fujiura A, Sakae K. Isolation and characterization of a new species of kobuvirus associated with cattle. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:3069–3077. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang F, Liu X, Zhou Y, Lyu W, Xu S, Xu Z, Zhu L. Histopathology of Porcine kobuvirus in Chinese piglets. Virol Sin. 2015;30:396–399. doi: 10.1007/s12250-015-3608-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]