Abstract

Two novel genomes comprising ≈4.9 kb were identified by next-generation sequencing from pooled organs of Tadarida brasiliensis bats. The overall nucleotide sequence identities between the viral genomes characterized here were less than 80 % in comparison to other polyomaviruses (PyVs), members of the family Polyomaviridae. The new genomes display the archetypal organization of PyVs, which includes open reading frames for the regulatory proteins small T antigen (STAg) and large T antigen (LTAg), as well as capsid proteins VP1, VP2 and VP3. In addition, an alternate ORF was identified in the early genome region that is conserved in a large monophyletic group of polyomaviruses. Phylogenetic analysis showed similar clustering with group of PyVs detected in Otomops and Chaerephon bats and some species of monkeys. In this study, the genomes of two novel PyVs were detected in bats of a single species, demonstrating that these mammals can harbor genetically diverse polyomaviruses.

Keywords: Rabies, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Multiple Displacement Amplification, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, Marburg Virus

Bats (order Chiroptera) are considered to be the natural reservoirs for a large variety of potentially zoonotic RNA viruses, such as lyssaviruses, paramyxoviruses, Ebola and Marburg viruses, and the recently emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus [1, 8, 19]. Several DNA viruses, including circoviruses [7], polyomaviruses [22], adenoviruses [15], parvoviruses [2] and herpesviruses [26], have also been detected in a number of bat species; however, their pathogenic and potential zoonotic role remain unclear.

Polyomaviruses (PyVs) are small DNA viruses of the family Polyomaviridae. Members of this family possess a double-stranded, circular genome, of approximately 5 kb. Viral genes have classically been subdivided into regulatory, early and late regions according to the order in which their role in replication is performed. The regulatory region, known as the noncoding control region (NCRR), is responsible for controlling transcription of the early and late promoters and regulating the initiation of viral DNA synthesis. After expression of the early region by a common primary transcript, splicing takes place to produce the large T antigen (LTAg) and small T antigen (STAg). The expression of the late region occurs after the initiation of replication and encodes the structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 [12].

Recently, a new protein was identified, expressed from an alternate frame of the large T open reading frame (ALTO) in the early region of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV). This protein was found to be phylogenetically related to the middle T antigen of murine polyomaviruses but not necessary for DNA replication. It has been suggested that ALTO may play an accessory role in the viral life cycle, similar to many other overprinting ORFs [3].

Using novel nucleic acid detection approaches, several PyVs have been identified in diverse mammalian species, including monkeys, elephants, cattle and rodents [17, 21]. In addition, PyVs have also been reported in birds [13]. In humans, to date, 10 PyVs have been discovered, including the well-studied JC and BK polyomaviruses, associated with multifocal leukoencephalopathy and nephropathy, respectively [20, 23].

Mutations, deletions and duplications within the highly variable NCCR region of PyVs are considered the primary mechanisms of host adaptation [24]. Apparently, PyVs have been co-diverging with their hosts on timescales of many millions of years [17]. Notwithstanding, a recent study on bats has partially refuted the virus-host relationship theory, given that distinctive PyVs have been identified in different bat species, providing evidence for extensive diversity [22].

In this study, we report the detection and genome characterization of two novel polyomaviruses in Tadarida brasiliensis bats, using high-throughput sequencing approaches.

Twelve Brazilian free-tailed bat specimens (Tadarida brasiliensis) were submitted to the laboratory (IPVDF) as part of the national rabies surveillance program. All specimens used in this study tested negative for rabies and were identified to the species level based on anatomical and morphological characteristics. Spleen, liver, lungs, kidneys and intestines were collected, pooled, macerated, centrifuged at low speed, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter for removal of small debris, and subjected to ultracentrifugation (200,000×g for 4 h). The pellet was mixed with nucleases to eliminate non-capsid-protected nucleic acids. DNA was then extracted with phenol-chloroform following usual procedures and enriched by multiple displacement amplification (MDA) [6]. After extraction, DNA was purified using a QIAGEN MinElute Purification Kit. The quality and quantity of the DNA were assessed using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer. DNA fragment libraries were further prepared with 50 ng of purified DNA using a Nextera DNA sample preparation kit and sequenced using an Illumina® MiSeq System.

Reads were assembled into contigs using SPAdes and compared to sequences in the GenBank nucleotide and protein databases using BLASTn/BLASTx. Geneious software was used for open reading frame (ORF) prediction and genome annotation. Multiple nucleotide sequence alignments were produced with the aid of MUSCLE. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with MrBayes v3.2.1 [9] using Bayesian analysis coupled with Markov chain Monte Carlo methods of phylogenetic inference. Analysis of the data sets showed the best-fitting evolutionary model to be the Whelan and Goldman (WAG) + Gamma model, which was applied for 100,000 generations, sampling 10 trees every 100 generations. Trees obtained before convergent and stable likelihood values were discarded (i.e., a 5,000 tree burn-in).

A total of 370,099 reads were produced. These sequences were assembled into 2,199 contigs, analyzed using BLAST with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databases, and 3,276 of these sequences were related to PyV. Two full-length circular genomes of novel polyomaviruses (GenBank accession numbers: KM655868 and KM655869) were identified. These were tentatively named Tadarida brasiliensis polyomavirus 1 and 2 (TbPyV1 and TbPyV2).

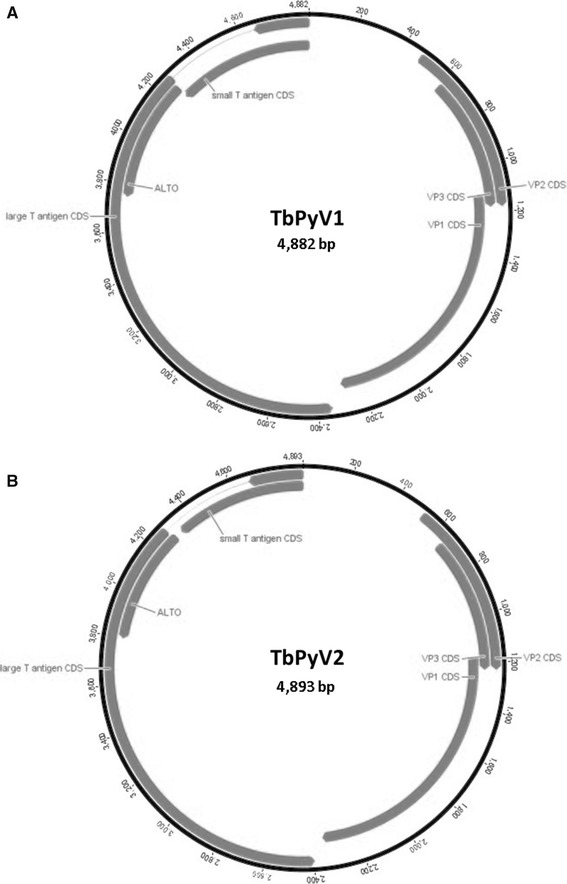

The two generated PyV genomes were 4,882 and 4,893 bp long, with 69.8 % whole-genome pairwise identity to each other. The overall GC content of TByV1 is 41.9 %, and that of TbPyV2 is 40.1 %, similar to those of previously described bat PyVs [22]. Both genomes display the archetypal genome organization of PyVs, including a region responsible for coding regulatory proteins STAg and LTAg, as well as other region coding for the capsid proteins VP1, VP2 and VP3 (Fig. 1). These two regions are separated by a non-coding regulatory region (NCCR) that is homologous to those of previously described polyomaviruses [10], showing nucleotide sequence identity ranging from 74 % to 78 % when compared to other bat PyVs (data not shown). The sizes and molecular weights of the deduced proteins encoded by both genomes are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the genome organization of Tadarida brasiliensis polyomaviruses 1 and 2 (TbPyV1 and TvPyV2). Putative coding regions for VP1 to VP3, small T antigen (STAg), large T antigen (LTAg), and the alternate large T open reading frame (ALTO) are marked by arrows

Table 1.

Main features of TbPyV-1 and TbPyV2 genomes

| Genome | TbPyV-1 (4,882 bp) | TbPyV-2 (4,893 bp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Position (nt) | Length (nt/aa) | MW (kDa) | Position (nt) | Length (nt/aa) | MW (kDa) |

| VP1 | 1133-2296 | 1164/387 | 42.2 | 1174-2358 | 1185/394 | 42.9 |

| VP2 | 478-1182 | 705/235 | 25.3 | 519-1229 | 711/237 | 25.7 |

| VP3 | 616-1182 | 570/190 | 20.9 | 654-1229 | 576/192 | 21.2 |

| Large T antigen | 4882-4664 | 2151/716 | 80.8 | 4893-4675 | 2106/701 | 79.8 |

| 4278-2347 | 4284-2398 | |||||

| Small T antigen | 4882-4268 | 615/204 | 24.1 | 4893-4330 | 564/187 | 22.0 |

| NCCR* | 1-477 | n/a | n/a | 1-518 | n/a | n/a |

| URR** | 2297-2346 | n/a | n/a | 2359-2397 | n/a | n/a |

*, noncoding region; **, upstream regulatory region

Analysis of the putative proteins revealed the presence, although sometimes modified, of the typical elements that are necessary for polyomaviruses to perform their replicative cycle. In the regulatory region of both genomes, several conserved elements were identified, including the AT-rich region, containing six copies of the consensus pentanucleotide LTAg binding site GAGGC and its reverse complement GCCTC [18]. These elements are likely to constitute the core of the origin of replication [14]. The LT-Ag is generated by alternative splicing of the early mRNA transcript. In the early region of both genomes, a conserved (CXXAG/GTXXX, with ‘/’ representing the breakpoint) splice donor site is located at base positions 4365 to 4369 (CCCAG/GTTTT) and 4372 to 4376 (CACAG/GTTTT) for TbPyV1 and TbPyV2, respectively. The LT-Ag region of both genomes varied from 701 to 716 aa (Table 1), showing less than 74 % similarity to the corresponding region of previously reported PyVs. In these protein sequences, the conserved “J” domain, which is responsible for efficient DNA replication and transformation, was identified [25]. In addition, a serine-rich profile, a zinc-binding motif (CX2CX7HX3HX2H), and an ATP/GTP-binding site (GPVNSGKT) were also identified [16, 21].

The STAgs in TbPyV1 and TbPyV2 each contain a cysteine-rich motif at the C-terminal end of the protein, which is nearly perfectly conserved in both genomes (CX7CX7CXCX17CX5CXCX2CX3WYG in TbPyV1, or WFG in TbPyV2).

VP1 is the major PyV structural protein. In the sequences identified, as expected, it is the most conserved ORF, containing the essential antigenic determinants for entry of the virus into host cells [12]. Both genomes have a proline-rich profile in the putative VP1, encompassing a 387 (TbPyV1)- or 394 (TbPyV2)-long amino acid chain. TbPyV1 VP1 had <78 % sequence identity when compared to those of other PyVs, whereas the one from TbPyV2 showed less than 83 % of identity with other bat PyVs.

In polyomaviruses, VP3 is usually encoded by the same open reading frame as VP2, using an internal initiation codon. In TbPyV1 and TbPvV2, the first methionine is positioned at amino acid 46 of the VP2 protein sequence and is considered to be the N-terminal amino acid of VP3, resulting in 190- and 192-aa-long protein sequences for genomes 1 and 2, respectively. The VP2 and VP3 proteins might play a role in viral entry and may ensure specific encapsidation of PyVs genomes [5, 12]. VP2/VP3-associated proteins from the two genomes reported here showed low sequence similarity (<72 % at the aa level) as well as different lengths when compared to each other and to other bat PyVs. In the minor capsid protein VP2 sequence, the N-terminal consensus sequence MGX4S, which is myristoylated in the avian polyomavirus VP2 [11], is found, but it is modified to MGX3S in both genomes.

The recently described alternate reading frame gene (called ALTO), which overlaps the LTAg gene [3], has been identified in TbPyV1 and TbPyV2 genomes and is represented in Figure 1. To our knowledge, this is the first description of this alternate ORF in bat polyomaviruses. ALTO is located at base positions 4268 to 3747 (TbPyV1) and 4298 to 3798 (TbPyV2), resulting in a 173- and 166-aa-long protein for genome 1 and 2, respectively.

The amino acid sequence similarity between the ALTO sequences described here and the one present in Otomops polyomavirus [22] is less than 82 %. On the other hand, when compared to each other, ALTO sequences from TbPyV1 and 2 showed low nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity (73 % and 58.3 %, respectively), with 72 % overall similarity.

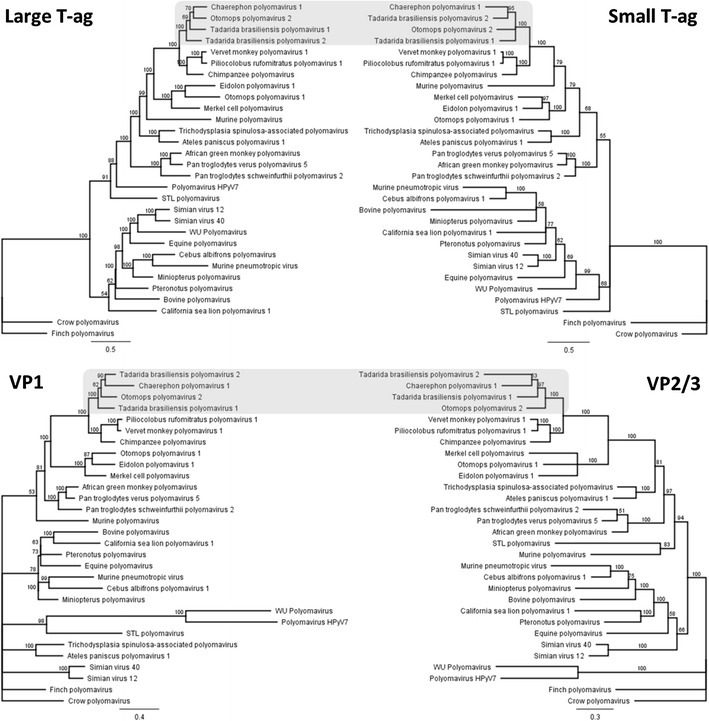

Figure 2 shows phylogenetic trees for LTAg, STAg and the structural proteins VP1, VP2 and VP3 of both polyomaviruses and those of 28 other polyomaviruses from mammals and birds, based on Bayesian analysis. Separate analyses of the proteins from TbPyV1 and 2 revealed similar clustering, with a heterogeneous group of PyVs detected in Otomops and Chaerephon bats and some species of monkeys (vervet monkey, Piliocolobus monkey, and chimpanzee), revealing a strong congruence. The relationship between PyVs of primates and bats supports the hypothesis of Tao et al., suggesting that PyVs have apparently “jumped” between bats and primates during evolutionary history; however, the direction of the host-switching event cannot be determined [22]. Our findings are also in accordance with those of Tao et al. [22], suggesting that bats are unlikely to be a direct source of PyV infection of humans, given that none of the bat sequences detected here and in previous studies seem to be related to known human PyVs.

Fig. 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic trees of the large and small T antigens, the major capsid protein VP1, and the minor capsid proteins VP2/VP3 of the novel bat PyV genomes. Amino acid sequences were compared to those of 28 polyomaviruses from mammals and birds, retrieved from GenBank. Posterior probability values are indicated above the branches. In these phylogenies, well-supported clades that contained the bat PyVs are shaded in gray

The newly characterized viruses belong to the proposed genus Orthopolyomavirus and differ genetically from the previously described bat polyomaviruses. According to the demarcation criteria set by the ICTV, a member of a novel PyV species should have <81-84 % sequence identity to other PyV genomes. The viruses described here all have <81 % sequence identity. In analogy with the nomenclature of the other bat polyomaviruses, we propose the name Tadarida brasiliensis polyomavirus (TbPyV) 1 and 2, for the newly discovered viruses.

Approximately 1200 bat species have been documented worldwide and more than 140 species are settled in Brazil [4]. The identification of distinct PyVs in bats of the same species sheds some light on the evolution and wide host range of these viruses, showing that bat of the same species can harbor multiple polyomaviruses. In this report, the genomes of two novel PyVs were detected in Tadarida brasiliensis bats. These viruses are genetically distinct from other PyVs recovered from bats and other mammals, suggesting that bats can play an important role in PyV evolution and ecology [22].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Council for the Improvement of Higher Education (CAPES), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP).

Footnotes

F. E. de Sales Lima and S. P. Cibulski contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Calisher CH, Childs JE, Field HE, Holmes KV, Schountz T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canuti M, Eis-Huebinger AM, Deijs M, de Vries M, Drexler JF, Oppong SK, Muller MA, Klose SM, Wellinghausen N, Cottontail VM, Kalko EK, Drosten C, van der Hoek L. Two novel parvoviruses in frugivorous New and Old World bats. PloS One. 2011;6:e29140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter JJ, Daugherty MD, Qi X, Bheda-Malge A, Wipf GC, Robinson K, Roman A, Malik HS, Galloway DA. Identification of an overprinting gene in Merkel cell polyomavirus provides evolutionary insight into the birth of viral genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12744–12749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303526110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa LP, Leite YLR, Mendes SL, Ditchfield AD. Mammal conservation in Brazil. Conserv Biol. 2005;19:672–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00666.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels R, Rusan NM, Wadsworth P, Hebert DN. SV40 VP2 and VP3 insertion into ER membranes is controlled by the capsid protein VP1: implications for DNA translocation out of the ER. Mol Cell. 2006;24:955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean FB, Hosono S, Fang L, Wu X, Faruqi AF, Bray-Ward P, Sun Z, Zong Q, Du Y, Du J, Driscoll M, Song W, Kingsmore SF, Egholm M, Lasken RS. Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082089499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge X, Li J, Peng C, Wu L, Yang X, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Shi Z. Genetic diversity of novel circular ssDNA viruses in bats in China. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2646–2653. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilgenfeld R, Peiris M. From SARS to MERS: 10 years of research on highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Antivir Res. 2013;100:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imperiale MJ, Major EO. Polyomaviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley P, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2263–2298. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johne R, Wittig W, Fernandez-de-Luco D, Hofle U, Muller H. Characterization of two novel polyomaviruses of birds by using multiply primed rolling-circle amplification of their genomes. J Virol. 2006;80:3523–3531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3523-3531.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johne R, Buck CB, Allander T, Atwood WJ, Garcea RL, Imperiale MJ, Major EO, Ramqvist T, Norkin LC. Taxonomical developments in the family Polyomaviridae. Arch Virol. 2011;156:1627–1634. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leon O, Corrand L, Bich TN, Le Minor O, Lemaire M, Guerin JL. Goose Hemorrhagic polyomavirus detection in geese using real-time PCR assay. Avian Dis. 2013;57:797–799. doi: 10.1637/10513-021013-ResNote.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Li BL, Hock M, Wang E, Folk WR. Sequences flanking the pentanucleotide T-antigen binding sites in the polyomavirus core origin help determine selectivity of DNA replication. J Virol. 1995;69:7570–7578. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7570-7578.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lima FE, Cibulski SP, Elesbao F, Carnieli Junior P, Batista HB, Roehe PM, Franco AC. First detection of adenovirus in the vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) in Brazil. Virus Genes. 2013;47:378–381. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0947-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeber G, Stenger JE, Ray S, Parsons RE, Anderson ME, Tegtmeyer P. The zinc finger region of simian virus 40 large T antigen is needed for hexamer assembly and origin melting. J Virol. 1991;65:3167–3174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3167-3174.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Losada M, Christensen RG, McClellan DA, Adams BJ, Viscidi RP, Demma JC, Crandall KA. Comparing phylogenetic codivergence between polyomaviruses and their hosts. J Virol. 2006;80:5663–5669. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00056-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pomerantz BJ, Hassell JA. Polyomavirus and simian virus 40 large T antigens bind to common DNA sequences. J Virol. 1984;49:925–937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.3.925-937.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pourrut X, Souris M, Towner JS, Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Gonzalez JP, Leroy E. Large serological survey showing cocirculation of Ebola and Marburg viruses in Gabonese bat populations, and a high seroprevalence of both viruses in Rousettus aegyptiacus. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siebrasse EA, Reyes A, Lim ES, Zhao G, Mkakosya RS, Manary MJ, Gordon JI, Wang D. Identification of MW polyomavirus, a novel polyomavirus in human stool. J Virol. 2012;86:10321–10326. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01210-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens H, Bertelsen MF, Sijmons S, Van Ranst M, Maes P. Characterization of a novel polyomavirus isolated from a fibroma on the trunk of an African elephant (Loxodonta africana) PloS One. 2013;8:e77884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao Y, Shi M, Conrardy C, Kuzmin IV, Recuenco S, Agwanda B, Alvarez DA, Ellison JA, Gilbert AT, Moran D, Niezgoda M, Lindblade KA, Holmes EC, Breiman RF, Rupprecht CE, Tong S. Discovery of diverse polyomaviruses in bats and the evolutionary history of the Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:738–748. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.047928-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Ghelue M, Khan MT, Ehlers B, Moens U. Genome analysis of the new human polyomaviruses. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:354–377. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White MK, Safak M, Khalili K. Regulation of gene expression in primate polyomaviruses. J Virol. 2009;83:10846–10856. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00542-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams CK, Vaithiyalingam S, Hammel M, Pipas J, Chazin WJ. Binding to retinoblastoma pocket domain does not alter the inter-domain flexibility of the J domain of SV40 large T antigen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;518:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Todd S, Tachedjian M, Barr JA, Luo M, Yu M, Marsh GA, Crameri G, Wang LF. A novel bat herpesvirus encodes homologues of major histocompatibility complex classes I and II, C-type lectin, and a unique family of immune-related genes. J Virol. 2012;86:8014–8030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00723-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]