Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a causative agent of porcine intestinal disease, which causes vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration in piglets. PEDV is associated with the most severe pathogenesis in one-week-old piglets, with mortality rates reaching 100%. A PEDV strain was isolated from the intestinal tract of diarrheic piglets from a pig farm in Jiangsu Province in March 2016, termed the JS201603 isolate. The isolated virus was confirmed to be PEDV via RT-PCR, electron microscopy, a cytopathic effect assay and sequence analysis. The S and ORF3 genes of the JS201603 isolate were sequenced, revealing that the S gene was associated with a 15-base insertion at 167 nt, 176 - 186 nt, and 427 - 429 nt, as well as a six-base deletion in 487 - 492 nt, indicating that it was a current epidemic variant compared with the classical strain, CV777. No deletion occurred between 245 - 293 nt of the ORF3 gene in the JS201603 isolate compared with the vaccine isolates YY2013 and SQ2014. An experimental infection model indicated that the piglets in the challenge group successively developed diarrhea, exhibiting yellow-colored loose stools with a foul odor. The piglets in the JS201603 isolate challenge group displayed reduced food consumption, lost weight, and in severe cases even died. No abnormalities were observed in the control group. The JS201603 variant isolated in this study contributes to the evolutionary analysis of diarrhea virus. The experimental infection model has established a foundation for further studies on vaccine development.

Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is a porcine infectious disease which primarily causes severe watery diarrhea, vomiting, marked emaciation and dehydration, and even death in suckling piglets [1, 2]. Outbreaks of porcine diarrhea have been reported sequentially in pig farms in England [3], Belgium [4], Canada [5], Germany [6] and Japan [7] from 1970 to 1990. In 1984 a coronavirus strain was isolated in China and termed porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) [8]. PEDV viruses are taxonomically classifiable within the genus Alphacoronavirus, family Coronaviridae and order Nidovirales [9], and consist of a 28 kb viral genome composed of a 5’ untranslated region, six open reading frames (ORF1, S, ORF3, E, M and N), and a 3’ untranslated region [10].

Incidents of diarrhea virus have been consistently reported after the turn of the century. In 2009, outbreaks of PED were reported in most areas of Southern Vietnam [11] with the infected piglets developing severe dehydration and dying within a week. In 2010, variant-induced diarrhea broke out in China resulting in the death of 1 million piglets over 10 provinces of Southern China, with a mortality rate ranging from 80% to 100% in piglets aged younger than seven days [12]. In 2012, it was reported that the detection rate of PEDV in 12 southern provinces of china was 61.11%. In addition, a variant strain was determined using sequencing and was characterized by the presence of 9 additional bp in the S gene, when compared to CV777, including an insertion of 15 bp and a deletion of 6 bp [13]. Since 2013, there have been outbreaks of PEDV in 14 American states, with mortality rates as high as 95% [14]. In March 2016, an outbreak of diarrhea in a large pig farm in Jiangsu province, China was reported, which had a severe impact on suckling piglets. The newborn piglets developed severe watery diarrhea and vomiting within 24 h of birth, with mortality rates as high as 90%, resulting in substantial losses to the pig farm. A strain of PEDV was isolated and identified from the diarrhea samples obtained at this pig farm. In addition, gene sequencing and pathogenicity experiments were performed, with the aim of establishing a foundation for future studies of PEDV vaccines.

Materials and methods

Virus isolation and propagation

Intestine samples from two-day-old piglets with diarrhea were collected from a large-scale outbreak in a pig farm in Jiangsu province (China) in 2016. Samples were confirmed to be PEDV-infected via multi-RT-PCR (PEDV, Porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus/TGEV, Porcine rotavirus/PoRV and porcine deltavirus/PDCoV). The sample was blended with DMEM (Gbico, USA) containing mycillin at a ratio of 1:8, centrifuged at 8000 rpm/min and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter. Next, 2, 4, 8 and 10-fold dilutions were carried out on the filtered fluid. The two-fold dilution was performed in DMEM containing 20 μg/mL trypsin (Gbico, USA) without EDTA, which was further diluted with DMEM containing 10 μg/mL trypsin. The diluted sample was then incubated at 37°C for 1 h and inoculated into 24-well plates (1 mL/well) containing a monolayer of Vero E6 cells. After the cytopathic effects were observed, the supernatants were collected. The virus was passaged with plaque clonal purification three times.

Virus titration

The Vero E6 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 105cells/well in 200 uL and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Ten-fold serial dilutions of the virus were added to the prepared wells with 100 uL of diluted virus per well. After five days of inoculation, the virus titres were determined, according to the Reed and Muench method [15].

Immunofluorescence assay and electron microscopy

Monolayers of Vero E6 cells were inoculated with PEDV at an MOI of 0.01 and incubated for 12 h at 37 °C. The cells were fixed with 80% ice-cold ethanol for 0.5 h at −20 °C. 100× diluted monoclonal antibody specific against PEDV was added to the cells as primary antibodies for 40 min at 37 °C followed by a 2000× of diluted FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cells were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope. Samples were prepared for electron microscopy (EM) as previously described [16].

RT-PCR

Sequence primers targeting the whole of the S and ORF3 genes were designed with reference to JX088695 and JX524137.1, as follows: (Forward: 5′-TGATGGGGAGAACGTGTCTAAAG-3′; Reverse: 5′-TGCAATTAG CTGTACAGGGTTGA-3′; Forward: 5′-TGTTGCACAAAGTGTTACA ACA-3′; Reverse: 5′-GAAACCTGAGAACACTTGAGT-3′; Forward: 5′-GACGTTTCTGGTTTTTGGACC-3′; Reverse: 5′-ACTAAAGTTGG TGGGAATAC-3′; Forward: 5′-AGTACTAGGGAGTTGCCTGGTT-3′; Reverse: 5′-GGGAATAAATGTCATCAATAGA-3′; Forward: 5′-AAGGG TTTGAACACTGTGGCTC-3′; Reverse:5′-AACAGATGTAGGTCAGC TTCT-3′; Forward: 5′-CTACTACACTTTCTTTTCTCAATG-3; Reverse: 5′-TGCGCTATTACACAACCGGTG-3′). PCR reactions were carried out in a buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 μM of each dNTP, 10 μM of each primer, 20 ng template DNA, and 2.5 U LA Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Japan) in a 50 μL total volume. The reaction was performed using an automated thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) under the following cycling conditions: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min; 34 cycles at 94 °C for 45s, 56 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; 1 cycle at 72 °C for 10 min. The product fragments ranged from 620 bp to 1634 bp. The PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel. The negative control for the PCR reactions was the PCR reaction mixture containing DMEM instead of the template DNA. Sequence assembly was carried out based on the sequencing results; moreover, sequence alignments of the S and ORF3 genes were also performed using the distance-based neighbor-joining method of MEGA 5.2 software.

The experimental infection model

Eight 1-day old piglets were obtained from Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Science (Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China). All piglets were confirmed to be free of PEDV, TGEV, PoRV and PDCoV infections, using a viral serum neutralizing test for the detection of antibodies against PEDV, TGEV, PoRV and PDCoV, as well as RT-PCR to detect viral nucleic acids. The piglets were divided randomly into two groups, each containing four animals. The infected group were orally challenged with F6 (passage 6) at 104.5 TCID50/mL (3 mL/piglet), while the uninfected group had PBS administered via the same route, as a control. The piglets were observed and recorded three times daily and humanely euthanized after the appearance of severe diarrhea or after becoming moribund. At the end of the study, all surviving piglets were euthanized humanely according to the instructions of Sinovet (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. At necropsy, different organ samples including intestine and stomach were fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin for hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E). The fixed intestine sections were evaluated for PEDV antigen by immunohistochemistry (IHC) using 200× diluted PEDV- specific monoclonal antibody with the antigen retrieval method described previously [17]. This study was approved by the local animal ethics committee.

Results

Virus isolation and characterization

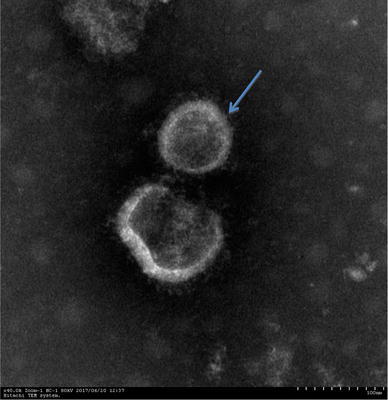

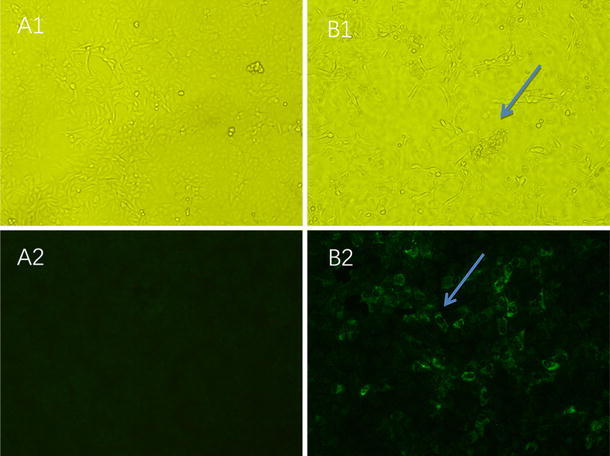

The samples were inoculated onto Vero E6 cells. At a 1:4 dilution, cytopathic effects appeared 36 h after the initial infection, and complete cytopathic effects were observed at 60 h. Such changes manifested as clustering, detachment, and syncytium formation. No cytopathic effects occurred in the control wells. Each of the sixth generations derived from the JS201603 isolate were found to be PEDV-positive via PCR. Structural analysis of the infected cells by electron microscopy confirmed that the PEDV virion was round and exhibited distinct radial projections (Fig. 1), which are typical characteristics of coronaviruses. Plaque clone purification was conducted three times and the purified virus was titrated to a titer of 104.5 TCID50/mL. Results from the immunofluorescence assay revealed that the attached fluorophore could be detected in infected Vero E6 cells, whereas none were detected in the control group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Electron microscopy images of coronavirus-like particles of strain JS201603 following infection of Vero E6 cells in cell culture media. Clear virus particles are shown by arrows. (Scale bars = 100 nm)

Fig. 2.

Cytopathic effects and an immunofluorescence assay of the PEDV isolate. A1 and A2 are uninfected controls. B1: At 40 h post-infection, the cytopathic effects were recorded as clustering, cell detachment and syncytium formation (indicated by the blue arrow). B2: Cells were examined by IFA using a PEDV-specific monoclonal antibody (indicated by the blue arrow)

Sequence analysis of the S gene

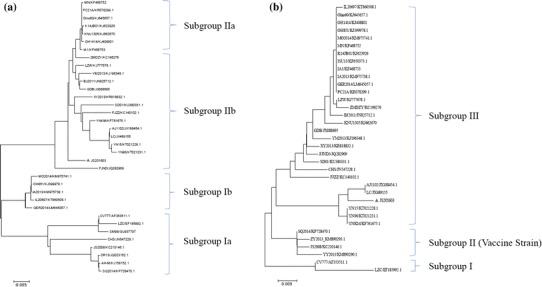

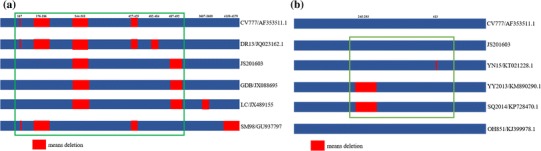

Sequencing of the S gene of the JS201603 isolate (Genbank number: KY607767) yielded a sequence of 4179 bp, which was analyzed through a comparison with 34 typical strains (Table 1, left part and labeled with blue color) available in NCBI. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3a) revealed that these PEDV strains could be divided into Subgroup I and Subgroup II. The American isolates were found to belong to Subgroup IIa, while the Chinese isolates were from Subgroup IIb. A nucleotide homology analysis indicated that the JS201603 isolate shared 93.7% to 94.4%, 96.1% to 96.4%, 98.9% to 99.0%, and 97.7% to 99% homology to Subgroup Ia, Subgroup Ib, Subgroup IIa, and Subgroup IIb, respectively. The JS201603 isolate shared the greatest homology with the IA1 [18] and BJ2011 [19] variants, and the lowest homology with the LZC isolate. The major variable region of the S gene was S1. Five typical strains, in addition to the JS201603 isolate were selected for analysis. Compared with the classical strain, CV777, the JS201603 and GDB isolates exhibited an insertion of 15 bases at 167 nt, 176 - 186 nt and 427 - 429 nt, as well as the deletion of six bases at 487 - 492 nt (Fig. 4a) [20]. The same insertions and deletions have been found in other variant strains isolated from other countries, indicating that epidemics are caused by variant strains in many countries. Moreover, the Korean vaccine DR13 isolate contained a deletion of bases at 482 - 484 nt [21]. The LC isolate [22] had an insertion of 15 bases and deletion of nine bases, and the SM98 isolate [23] exhibited a deletion of 21 bases at 4159 - 4179 nt. In comparison with the CV777 strain, some amino acid substitutions in the neutralizing region of COE (499 - 638aa) were observed, such as 558T-S, 603G-S, 614A-E, and 621L-F. The sequence analysis revealed that the other variant strains had the same COE mutations.

Table 1.

Comparison of nucleotide sequences (% nucleotide sequence identity) of the S (left part, labeled with blue color) and ORF3 (right part, labeled with red color) genes of the JS201603 isolate with other strains

| Strain | Genbank Accession no |

Country | Identity (S) |

Strain | Genbank Accession no |

Country | Identity (ORF3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MN | KF468752 | USA | 98.9% | IL20697 | KT860508.1 | USA | 96.0% |

| PC21A | KR078299.1 | USA | 99.0% | Ohio60 | KJ645657.1 | USA | 96.1% |

| Ohio60 | KJ645657.1 | USA | 99.0% | OH1414 | KJ408801 | USA | 96.1% |

| K14JB | KJ623926 | Korea | 98.9% | OH851 | KJ399978.1 | USA | 96.1% |

| KNU1305 | KJ662670 | Korea | 98.9% | MO2014 | KM975741.1 | USA | 96.1% |

| OH1414 | KJ408801 | USA | 98.9% | MN | KF468752 | USA | 96.1% |

| IA1 | KF468753 | USA | 99.0% | K14JB01 | KJ623926 | Korea | 96.1% |

| ZMDZY | KC196276 | China | 98.7% | ISU13 | KF650373.1 | USA | 96.1% |

| LZW | KJ777678.1 | China | 98.9% | IA1 | KF468753 | USA | 96.1% |

| YM2013 | KJ196348.1 | China | 98.6% | IA2013 | KM975738.1 | USA | 96.1% |

| BJ2011 | JN825712.1 | China | 99% | GER2014 | LM645057.1 | Germany | 96% |

| GDB | JX088695 | China | 98.8% | PC21A | KR078299.1 | USA | 96.1% |

| XY2013 | KR818832.1 | China | 98.6% | LZW | KJ777678.1 | China | 96.3% |

| SD01 | KU380331.1 | China | 98.0% | ZMDZY | KC196276 | China | 96% |

| FJZZ | KC140102.1 | China | 98.1% | BJ2011 | JN825712.1 | China | 96% |

| YNKM | KF761675.1 | China | 98.6% | KNU1305 | KJ662670 | Korea | 96% |

| AJ1102 | JX188454.1 | China | 98.0% | GDB | JX088695 | China | 96.4% |

| LC | JX489155 | China | 98.1% | YM2013 | KJ196348.1 | China | 96% |

| YN15 | KT021228.1 | China | 98.0% | XY2013 | KR818832.1 | China | 96.3% |

| YN90 | KT021231.1 | China | 97.8% | FJND3 | JQ282909 | China | 96.3% |

| FJND | JQ282909 | China | 97.7% | SD01 | KU380331.1 | China | 96.4% |

| MO2014 | KM975741.1 | USA | 96.1% | CHS | JN547228.1 | China | 96.3% |

| OH851 | KJ399978.1 | USA | 96.3% | FJZZ | KC140102.1 | China | 96.9% |

| IA2013 | KM975738.1 | USA | 96.3% | AJ1102 | JX188454.1 | China | 98.7% |

| IL20697 | KT860508.1 | USA | 96.2% | LC | JX489155 | China | 98.7% |

| GER2014 | LM645057.1 | Germany | 96.4% | YN15 | KT021228.1 | China | 98.7% |

| CV777 | AF353511.1 | Switzerland | 94.2% | YN90 | KT021231.1 | China | 98.7% |

| LZC | EF185992.1 | China | 93.7% | YNKM | KF761675.1 | China | 98.7% |

| SM98 | GU937797 | Korea | 93.9% | SQ2014 | KP728470.1 | China | 96.8% |

| CHS | JN547228.1 | China | 94.1% | ZY2013 | KM890293.1 | China | 96.5% |

| JS2008 | KC210146.1 | China | 94.4% | JS2008 | KC210146.1 | China | 96.5% |

| DR13 | JQ023162.1 | Korea | 94.2% | YY2013 | KM890290.1 | China | 96.3% |

| AH-M | KJ158152.1 | China | 94.1% | CV777 | AF353511.1 | Switzerland | 96.1% |

| SQ2014 | KP728470.1 | China | 94.1% | LZC | EF185992.1 | China | 94.8% |

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the entire nucleotide sequences of the S gene (a) and ORF3 gene (b) of the PEDV JS201603 isolate (▲). a) The phylogenetic tree revealed that the PEDV strains could be divided into Subgroup I and Subgroup II according to the sequencing of the S gene. The JS201603 isolate shared the highest homology with subgroup IIb viruses. b) The phylogenetic tree showed that the JS201603 isolate belonged to subgroup II and shared the lowest genetic distance with the vaccine strains

Fig. 4.

A map of deleted fragments in the S region (a) and ORF3 region (b) of the genome. a) Compared with the classical strain, CV777, the JS201603 and GDB isolates exhibited an insertion of 15 bases at 167 nt, 176-186 nt and 427-429 nt, as well as the deletion of six bases at 487-492 nt. b) The analysis of nucleotide deletions suggested that, when compared with the JS201603 isolate, YY2013 and SQ2014 isolates (vaccine strains) had a 49 nt deletion at 245-293 nt. Of the selected strains, only YN15 had a deletion at 413 nt

Sequence analysis of ORF3

The ORF3 gene of the JS201603 isolate was 675 bp in length. A total of 34 ORF3 genes from domestic and foreign strains (Table 1, right part and labeled with red color) were selected for sequence analysis. A phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3b) revealed that all strains could be divided into Subgroup I, Subgroup II, and Subgroup III. The JS201603 isolate (Genbank number: KY607768) exhibited 94.8% to 96.1%, 96.3% to 96.8%, 96% to 96.1%, and 96% to 98.7% homology to Subgroup I, Subgroup III, the American and Korean strains in Subgroup II, and the Chinese isolates, respectively. The analysis of nucleotide deletions suggested that compared with the JS201603 isolate, the YY2013 and SQ2014 isolates (vaccine strains) had a 49 nt deletion at 245 - 293 nt (Fig. 4b) [24]. Of the selected strains, only YN15 had a deletion at 413 nt [25].

PEDV experimental infection model

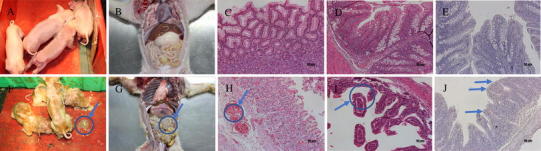

The piglets in both groups were determined to be healthy before challenge. The piglets in the infected group developed symptoms of diarrhea at 11 h post-challenge. Furthermore, the infected piglets presented with anorexia and depression. The piglets began to exhibit watery diarrhea at 24 h post-challenge. At 36 h, watery and explosive diarrhea followed, and some animals presented symptoms of vomiting after suckling. One piglet died 72 h post-challenge, while the remaining piglets were moderately depressed and curled up in the corners of their enclosure, with an associated loss of appetite. The most severe diarrhea was exhibited at 96 h post-challenge, at which time the piglets could not stand stably, and showed signs of severe emaciation and anorexia. Another piglet died at 102 h post-challenge. No abnormalities were found in the uninfected group (Fig. 5A, 5F). There was a significant decrease in weight in the infected group post-challenge, whereas the uninfected piglets gained weight. No obvious temperature changes were observed between the two groups. At necropsy, the gross lesions were found to be confined to the gastrointestinal tract, characterized by a distended stomach filled with undigested milk curd (Fig. 5B, 5G), and transparent intestine walls with the accumulation of yellowish fluids [26]. The results of the histopathologic examination revealed necrosis of scattered enterocytes followed by sloughing, the contraction of the subjacent villous lamina propria containing apoptotic cells, and a reduction in the intestinal villi compared with the controls (Fig. 5C, 5D, 5H, 5I). Immunohistochemistry for PEDV confirmed the presence of virus in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells on atrophied villi in some segments of the small intestines. No PEDV IHC antigens were noted in the intestines of uninfected piglets (Fig. 5E, 5J).

Fig. 5.

The tissues of infected and uninfected groups were grossly and histologically examined, as follows: A, B, C(stomach), D(intestine), E(intestine) from control animals. F: The piglets were anorexic, depressed, and their faeces were watery (indicated by the blue arrow). G: Transparent intestine walls (indicated by the blue arrow) with accumulation of yellowish fluids were observed in the infected piglets. H: Gastric hemorrhage in the infected piglets (indicated by the blue arrow). I: Contraction of the subjacent villous lamina propria containing apoptotic cells, as well as the intestinal villi being reduced (indicated by the blue arrow). J: For IHC assays, the intestinal tissue sections were stained with PEDV monoclonal antibody (1:200 dilution). Positive infected cells present in a segment of the intestines (indicated by the blue arrow)

Discussion

A strain of PEDV was successfully isolated in this study, referred to as the JS201603 isolate. The sample was diluted to infect Vero E6 cells, with cytopathic effects appeared during the first generation of infection and continuing into later generations. PCR and indirect immunofluorescence assays indicated that the JS201603 isolate was PEDV, and no other viruses were detected. Sequence analysis of the S and ORF3 genes demonstrated that the JS201603 isolate was a variant strain. Homology analysis revealed that the JS201603 isolate shared greater homology with subgroup II than with subgroup I. Furthermore, there was no deletion of 49 nt bases in the ORF3 gene and the JS201603 isolate exhibited low homology with the vaccine strain. The results obtained using an experimental infection model suggested that the isolate could induce distinct clinical symptoms in piglets. The intestine samples were collected from a pig farm where the pigs had been previously immunized with the PEDV CV777 attenuated vaccine in August 2015 and the PEDV-TGEV live attenuated vaccine in February 2016; however, further investigation as to whether the isolate strain was derived from the recombination of vaccine strains is still required. It could be determined that the existing CV777 vaccine strain on the market exhibited lower protective efficacy against the occurrence of diarrhea. This data is consistent with the 2013 report which stated that pig farms immunized with the CV777 inactivated vaccine experienced PEDV outbreaks [19].

Further studies are required regarding the origin of PEDV variants. In 2009, Lee et al. first reported a PEDV variant in Korea and found that the S gene of the variant isolate contained 9 bp more than other strains [27]. In addition, most of the variable regions were concentrated at the N-terminus of the S gene. Outbreaks of diarrhea virus were reported in the US in 2013, for which phylogenetic analysis suggested that the three variant strains from the US shared the greatest homology with a diarrhea isolate obtained from Anhui province (China) in 2012 [28]. In addition, 21 counties in Japan experienced PEDV outbreaks in 2014, which caused the death of approximately 40,000 piglets. Ma.T et al, suggested that the diarrhea virus outbreak was unrelated to invalid immunity to vaccines; instead, it was found to be caused by an epidemic variant strain [29]. Although some groups have reported that the morbidity caused by diarrhea has decreased since 2015, greater attention should continue to be paid to its prevention and control.

Compared with the classical strain, the 1 - 1180 bp region in the S1 gene of PEDV variants is highly prone to variability [30]. As this region contains the receptor binding domain, further studies are required to determine whether this PEDV outbreak was caused by variation in the receptor binding of variant strains [31]. Thousands of piglets have died as a result of diarrhea virus infection since 2010 in China. Thus, an effective vaccine is critical to reduce the economic losses experienced within the pig breeding industry. The variant isolate characterized in this study contributes to the evolutionary analysis of diarrhea viruses. The effective experimental model of infection used in this study has established a foundation for further research on PEDV vaccine development.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Research and Development of Sinovet (Beijing) Biotechnology Co,.Ltd. The research results belonged to Sinovet (Beijing) Biotechnology Co,.Ltd. Thanks to Wenjie Jin for helping the epidemic survey.

Author contributions

HZ, SC, SZ, NS, CZ, KD, HW designed the study. HZ, MX, DJ, CN, XW, YW, BW, TF, FC, WW performed the experiments. HZ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. XC, KD revised the manuscript. WJ helped collecting the samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist and no conflicts of interest exist.

Ethical standards

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Sinovet (Beijing) Biotechnology Co,. Ltd (SYXK:2013-0032).

Contributor Information

Ke Ding, Email: keding19@163.com.

Hua Wu, Email: wuhuasinovetah@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Song D, Park B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes. 2012;44:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pensaert M, De Bouck P. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch Virol. 1978;58:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flewett T, Boxall E. The hunt for viruses in infections of the alimentary system: an immunoelectron-microscopical approach. Clin Gastroentero l. 1976;5:359–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNulty M, Curran W, McFerran J. Virus-like particles in calves’s faeces. Lancet. 1975;306:78–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90524-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akashi H, Inaba Y, Miura Y, Tokuhisa S, Sato K, Satoda K. Properties of a coronavirus isolated from a cow with epizootic diarrhea. Vet Microbiol. 1980;5:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(80)90025-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddell S, Wege H, Ter Meulen V. The biology of coronaviruses. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:761–776. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-4-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhutani O. Propagation and attenuation of a cylindrical blast wave in magnetogasdynamics. J Math Anal Appl. 1966;13:565–576. doi: 10.1016/0022-247X(66)90050-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xuan H, Xing D, Wang D, Zhu W, Zhao F, Gong H, Fei S. The study on culturing porcine epidemic diarrhea virus with porcine fetal monolayer cell. Chin J Vet Sci. 1984;4:202–208. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann M, Wyler R. Serologic study of the occurrence of epizootic viral diarrhea in swine in Switzerland. Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde. 1987;129:437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li ZL, Zhu L, Ma JY, Zhou QF, Song YH, Sun BL, Chen RA, Xie QM, Bee YZ. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) field strains in south China. Virus Genes. 2012;45:181–185. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0735-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SY, Goldie SJ, Salomon JA. Cost-effectiveness of Rotavirus vaccination in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Wang C, Shi H, Qiu H, Liu S, Chen X, Zhang Z, Feng L. Molecular epidemiology of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in China. Arch Virol Arch Virol. 2010;155:1471–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0720-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao J, Xue C, He L, Wang Y, Cao Y. Bioinformatics insight into the spike glycoprotein gene of field porcine epidemic diarrhea strains during 2011–2013 in Guangdong, China. Virus Genes. 2014;49:58–67. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1055-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marthaler D, Jiang Y, Otterson T, Goyal S, Rossow K, Collins J. Complete genome sequence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain USA/Colorado/2013 from the United States. Genome Announc. 2012;1(4):e00555-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00555-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doane FW, Anderson N (1987) Electron microscopy in diagnostic virology: a practical guide and atlas. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- 17.Jung K, Wang Q, Scheuer KA, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Saif LJ. Pathology of US porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain PC21A in gnotobiotic pigs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(4):662–665. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YW, Dickerman AW, Piñeyro P, Li L, Fang L, Kiehne R, Opriessnig T, Meng XJ. Origin, evolution, and genotyping of emergent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains in the United States. Mbio. 2013;4:00737–00713. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00737-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Y, Kou Q, Ge X, Zhou L, Guo X, Yang H. Phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus field strains prevailing recently in China. Arch Virol. 2013;158:711–715. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, Zhang J, Deng X, Ye Y, Liao M, Fan H. Complete genome sequence of a highly prevalent isolate of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in South China. J Virol. 2012;86:9551. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01455-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SJ, Kim HK, Song DS, An DJ, Park BK. Complete genome sequences of a Korean virulent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and its attenuated counterpart. J Virol. 2012;86:5964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00557-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen F, Pan Y, Zhang X, Tian X, Wang D, Zhou Q, Song Y, Bi Y. Complete genome sequence of a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain isolated in China. J Virol. 2012;86:12448. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02228-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Kim Y, Lee C. Isolation and characterization of a Korean porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain KNU-141112. Virus Res. 2015;208:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan Y, Tian X, Li W, Zhou Q, Wang D, Bi Y, Chen F, Song Y. Isolation and characterization of a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in China. Virol J. 2012;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen F, Zhu Y, Wu M, Ku X, Ye S, Li Z, Guo X, He Q. Comparative genomic analysis of classical and variant virulent parental/attenuated strains of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Viruses. 2015;7:5525–5538. doi: 10.3390/v7102891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: an emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol J. 2015;12:193. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee D-K, Park C-K, Kim S-H, Lee C. Heterogeneity in spike protein genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses isolated in Korea. Virus Res. 2010;149:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marthaler D, Jiang Y, Otterson T, Goyal S, Rossow K, Collins J. Complete genome sequence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain USA/Colorado/2013 from the United States. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00555–00513. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00555-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda T, Murakami S, Takahashi O, Miyazaki A, Ohashi S, Yamasato H, Suzuki T. New porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus variant with a large deletion in the spike gene identified in domestic pigs. Arch Virol. 2015;160:2565–2568. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2522-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato T, Takeyama N, Katsumata A, Tuchiya K, Kodama T, Kusanagi K. Mutations in the spike gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus associated with growth adaptation in vitro and attenuation of virulence in vivo. Virus Genes. 2011;43:72–78. doi: 10.1007/s11262-011-0617-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu M, Chen F, Li Z, Wan S, Ye S, He Q. Isolation, identification and full length genome sequence analysis of a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus-CH/YNKM-8/2013. J Huazhong Agric Univ. 2016;4:016. [Google Scholar]