Abstract

Equine coronavirus has been responsible for several outbreaks of disease in the United States and Japan. Only one complete genome sequence (NC99 isolated in the US) had been reported for this pathogenic RNA virus. Here, we report the complete genome sequences of three equine coronaviruses isolated in 2009 and 2012 in Japan. The genome sequences of Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 were 30,782, 30,916 and 30,916 nucleotides in length, respectively, excluding the 3’-poly (A) tails. All three isolates were genetically similar to NC99 (98.2–98.7 %), but deletions and insertions were observed in the genes nsp3 of ORF1a, NS2 and p4.7.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00705-015-2565-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Complete Genome Sequence, Japanese Isolate, Gene Nsp3, Total Nucleic Acid Isolation, Porcine Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis Virus

Equine coronavirus (ECoV) is an enveloped, positive-stranded RNA virus belonging to the species Betacoronavirus 1 in the genus Betacoronavirus. Several outbreaks of ECoV, characterized by clinical symptoms of fever, anorexia, lethargy, leucopenia, and digestive problems, have been reported in the United States [1] and Japan [2, 3]. These clinical signs were reproduced in our experimental challenge study [4]. However, to the best of our knowledge, only four ECoV strains have been isolated in the United States and Japan, and the complete genome sequence of this pathogen is only available for one American strain (NC99) [5]. To improve the molecular diagnosis of ECoV and to better understand its epidemiology, more genomic sequence data are required. Therefore, in this study, we determined the complete genome sequences of the remaining three ECoV strains isolated in Japan and compared them with that of NC99.

Three ECoVs, Tokachi09, isolated in 2009 [2], Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2, isolated in 2012 [3], were analyzed in this study. These ECoVs were isolated from adult horses showing symptoms of diarrhea at Obihiro Racecourse, Hokkaido, Japan. Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 were passaged 4 to 5 times in HRT-18G cells [2, 3]. Viral RNA was extracted using a MagNA Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). RT-PCR was performed with six primer sets designed based on the complete genome sequence of NC99 (GenBank accession number: NC_010327) (Supplementary Table 1). RT-PCR was performed using a PrimeScript II High Fidelity RT-PCR Kit or PrimeScript II High Fidelity One Step RT-PCR Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan).

These PCR amplicons were sequenced using Ion Torrent technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Libraries were constructed using an Ion Xpress Plus Fragment Library Kit and an Ion Xpress Barcode Adapters Kit. Emulsion PCR, enrichment and loading onto an Ion 318 Chip were performed automatically using Ion Chef, and sequencing was conducted in the Ion PGM system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As a result, we obtained more than 140 million nucleotides (nt) for each ECoV, and the average depth was 14859.2 times. The raw signal data were analyzed using Torrent Suite version 4.4.1, and NC99 was used as a reference sequence. The reads with more than 100 bases that could be mapped to the reference sequence were used. Torrent Variant Caller version 4.2 was used to call the mutated sites, and the most frequently observed alleles were selected in each of the called positions. Bases within the reference sequence were substituted with the observed alleles if frequencies exceeded 50 %.

The 5’- and 3’-end sequences were determined by Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) using a GeneRacer Kit with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a 3’-Full RACE Core Set (Takara), respectively. The primers used for 5’/3’ RACE are shown in Supplementary Table 1. PCR was conducted using HotStarTaq Plus DNA Polymerase (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The amplified products were cloned using a TOPO TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the plasmids were sequenced commercially (Fasmac, Atsugi, Japan) using an M13 universal primer. At least three clones were sequenced per amplified product. Sequences were analyzed and assembled using the Vector NTI Advance 11 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Phylogenetic analysis of the nucleic acid sequences was conducted using MEGA 5.2 software [6]. Phylogenetic trees based on complete genome sequences were constructed using the neighbor-joining method. Statistical analysis of the trees was conducted using the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates).

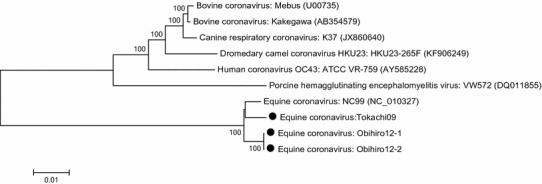

The complete genome sequences of Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 were 30,782, 30,916 and 30,916 nt in length, respectively, excluding the 3’-poly (A) tails. The accession numbers registered in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases for these genome sequences are as follows: Tokachi09 (LC061272), Obihiro12-1 (LC061273) and Obihiro12-2 (LC061274). The complete genome of NC99 shared 98.2 % nt sequence identity with Tokachi09, 98.7 % with Obihiro12-1, and 98.7 % with Obihiro12-2. Phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1) showed that ECoVs grouped separately from other members of the species Betacoronavirus 1, and Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2, isolated during the same outbreak, were closely related.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the complete genome sequences of members of the species Betacoronavirus 1. The three equine coronavirus strains examined in this study are indicated by closed circles. The percent bootstrap support is indicated by the value at each node, and values less than 70 % are omitted

Putative genes of Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 are shown in Table 1, and were compared with the genes published previously for NC99 [5]. The 5’ untranslated region (UTR) spanned nt 1 to 208 in the three Japanese ECoVs, and the 3’-UTR spanned nt 30,494 to 30,782 in Tokachi09 and nt 30,628 to 30,916 in Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2. All three Japanese isolates exhibited a 1-nt deletion (nt 1) compared with isolate NC99. The 5’- and 3’-UTRs were highly conserved between NC99 and the three Japanese isolates (5’-UTR, 98.6 %; 3’-UTR, 97.6–99.3 %).

Table 1.

Comparison of putative genes in NC99 with those in Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2

| Gene | NC99a | Tokachi09 | Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome position | No. of nucleotides | No. of amino acids | Genome position | No. of nucleotides | No. of amino acids | Genome position | No. of nucleotides | No. of amino acids | |

| 5’ UTR | 1–209 | 209 | 1-208 | 208 | 1-208 | 208 | |||

| ORF1a | 210–13,499 | 13,290 | 4429 | 209-13,474 | 13,266 | 4,421 | 209-13,465 | 13,257 | 4,418 |

| ORF1ab | 210–21,595 | 21,386 | 7128 | 209-21,570 | 21,362 | 7,120 | 209-21,561 | 21,353 | 7,117 |

| NS2 | 21,610–22,446 | 837 | 278 | 21,585-22,421 | 837 | 278 | 21,576-22,160 | 585 | 194 |

| HE | 22,458–23,729 | 1,272 | 423 | 22,433-23,704 | 1,272 | 423 | 22,422-23,693 | 1,272 | 423 |

| S | 23,744–27,835 | 4,092 | 1363 | 23,719-27,810 | 4,092 | 1,363 | 23,708-27,799 | 4,092 | 1,363 |

| p4.7 | 27,825–27,947 | 123 | 40 | 27,800-27,841 | 42 | 13 | 27,789-27,812 | 24 | 7 |

| p12.7 | 28,076–28,405 | 330 | 109 | 27,866-28,195 | 330 | 109 | 28,000-28,329 | 330 | 109 |

| E | 28,392–28,646 | 255 | 84 | 28,182-28,436 | 255 | 84 | 28,316-28,570 | 255 | 84 |

| M | 28,661–29,353 | 693 | 230 | 28,451-29,143 | 693 | 230 | 28,585-29,277 | 693 | 230 |

| N | 29,363–30,703 | 1,341 | 446 | 29,153-30,493 | 1,341 | 446 | 29,287-30,627 | 1,341 | 446 |

| I | 29,424–30,044 | 621 | 206 | 29,214-29,834 | 621 | 206 | 29,348-29,968 | 621 | 206 |

| 3’ UTR | 30,704–30,992 | 289 | 30,494-30,782 | 289 | 30,628-30,916 | 289 | |||

aSequence data of NC99 are from Zhang et al [5]

ORF1a was located at nt 209–13,474 in Tokachi09 and nt 209–13,465 in Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2. The sequence encoding the nsp3 protein within ORF1a contained a 9-nt insertion (nt 3,175–3,183) in Tokachi09. In addition, a 33-nt deletion compared with NC99 was observed between 6,361 and 6,362 in Tokachi09, and between 6,352 and 6,353 in Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2. Other betacoronaviruses, such as bovine coronavirus, porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus, and human coronavirus OC43, harbor longer deletions in the same region, indicating that this region may be prone to deletion mutations. Due to these deletions and insertions, ORF1a in Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 was 24, 33 and 33 nt shorter than in NC99. Overall, ORF1a and ORF1ab were highly conserved between NC99 and the three Japanese ECoVs (ORF1a, 98.4–99.0 % for nt and 97.8–98.9 % for amino acid [aa]; ORF1ab, 98.9–99.1 % for nt and 98.6–99.1 % for aa).

The NS2 nt and aa sequences were identical in length between isolates Tokachi09 and NC99 and were highly conserved in sequence (98.6 % for nt and 97.8 % for aa). In contrast, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 contained a 2-nt deletion (between 22,159 and 22,160) compared with NC99 and Tokachi09. This deletion created an additional stop codon, truncating the NS2 open reading frame by 84 aa in these isolates compared with NC99 and Tokachi09. This deletion also created a start codon downstream of this stop codon, and another open reading frame (nt 22,186–22,410) may therefore exist in Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2.

Between genes p4.7 and p12.7, we reconfirmed that Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2 harbored deletions totaling 185, 40 and 40 nt, respectively, compared with NC99, as reported previously [2, 3]. These deletions would drastically shorten the length of the putative p4.7 gene. However, it is yet to be confirmed that the p4.7 gene is expressed and functional in these three Japanese ECoVs.

The nt lengths of the HE, S, p12.7, E, M, N and I genes were identical between NC99 and the three Japanese isolates, and the nt and aa sequences of these genes were highly conserved: HE, 97.5–98.0 % for nt and 96.5–97.9 % for aa; S, 98.5–99.0 % for nt and 98.5–99.0 % for aa; p12.7, 99.1 % for nt and 99.1–100 % for aa; E, 98.4–99.6 % for nt and 98.8–100 % for aa; M, 98.7–99.3 % for nt and 99.1–100 % for aa; N, 98.0–98.2 % for nt and 97.3–97.5 % for aa; I, 97.4–98.1 % for nt and 95.1–95.6 % for aa.

In conclusion, three ECoV isolates from Japan (Tokachi09, Obihiro12-1 and Obihiro12-2) are genetically similar to NC99, isolated in the United States, with the exception of the nsp3, NS2 and p4.7 genetic regions. It will now be interesting to investigate whether these mutations alter the antigenicity and pathogenicity of ECoV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Chihiro Yoshihara (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Wako, Japan) and Mr. Yoshinori Morita for their invaluable advice.

Footnotes

M. Nemoto and Y. Oue contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Pusterla N, Mapes S, Wademan C, White A, Ball R, Sapp K, Burns P, Ormond C, Butterworth K, Bartol J, Magdesian G. Emerging outbreaks associated with equine coronavirus in adult horses. Vet Microbiol. 2013;162:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oue Y, Ishihara R, Edamatsu H, Morita Y, Yoshida M, Yoshima M, Hatama S, Murakami K, Kanno T. Isolation of an equine coronavirus from adult horses with pyrogenic and enteric disease and its antigenic and genomic characterization in comparison with the NC99 strain. Vet Microbiol. 2011;150:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oue Y, Morita Y, Kondo T, Nemoto M. Epidemic of equine coronavirus at Obihiro racecourse, Hokkaido, Japan in 2012. J Vet Med Sci. 2013;75:1261–1265. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemoto M, Oue Y, Morita Y, Kanno T, Kinoshita Y, Niwa H, Ueno T, Katayama Y, Bannai H, Tsujimura K, Yamanaka T, Kondo T. Experimental inoculation of equine coronavirus into Japanese draft horses. Arch Virol. 2014;159:3329–3334. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Guy JS, Snijder EJ, Denniston DA, Timoney PJ, Balasuriya UB. Genomic characterization of equine coronavirus. Virology. 2007;369:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.