Abstract

A multiplex polymerase chain reaction (mPCR) assay was developed to detect and distinguish feline panleukopenia virus (FPV), feline bocavirus (FBoV) and feline astrovirus (FeAstV). Three pairs of primers were designed based on conserved regions in the genomic sequences of the three viruses and were used to specifically amplify targeted fragments of 237 bp from the VP2 gene of FPV, 465 bp from the NP1 gene of FBoV and 645 bp from the RdRp gene of FeAstV. The results showed that this mPCR assay was effective, because it could detect at least 2.25-4.04 × 104 copies of genomic DNA of the three viruses per μl, was highly specific, and had a good broad-spectrum ability to detect different genotypes of the targeted viruses. A total of 197 faecal samples that had been screened previously for FeAstV and FBoV were collected from domestic cats in northeast China and were tested for the three viruses using the newly developed mPCR assay. The total positive rate for these three viruses was 59.89% (118/197). From these samples, DNA from FPV, FBoV and FeAstV was detected in 73, 51 and 46 faecal samples, respectively. The mPCR testing results agreed with the routine PCR results with a coincidence rate of 100%. The results of this study show that this mPCR assay can simultaneously detect and differentiate FPV, FBoV and FeAstV and can be used as an easy, specific and efficient detection tool for clinical diagnosis and epidemiological investigation of these three viruses.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00705-019-04394-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Cats are among the most common companion animals and play an important role in providing emotional support for people. To date, the population of domestic cats kept by humans worldwide is estimated at 80-400 million [17], and humans are increasingly paying more attention to the health of cats. Viral diarrhea is common in cats, especially in young kittens, and it is also a major threat to their health. It is commonly recognized that feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) is the major virus that causes diarrhea in cats [21]. Over the past few years, more diarrhea-related viruses, such as feline bocavirus (FBoV) [10], feline astrovirus (FeAstV) [11] and feline kobuvirus (FeKoV) [4], have been described in cats, and new detection techniques have been developed and applied [17].

FPV, a member of the species Carnivore protoparvovirus 1, which belongs to the genus Protoparvovirus within the family Parvoviridae, is a highly contagious pathogen in domestic and wild cats [1]. FPV is transmitted by the faecal-oral route and primarily infects young kittens aged 3-6 months [15, 21], resulting in severe enteric and immunosuppressive diseases characterized by fever, depression, anorexia, vomiting, acute diarrhea, haemorrhagic enteritis and leukopenia [16]. At present, FPV is widely spread throughout the world, with a high mortality rate of 25% to 90% [18], and represents a serious threat to the life and health of cats. Furthermore, infections with canine parvovirus 2a, 2b and 2c (CPV-2a, -2b and -2c) have also been described in domestic cats in many countries [18]. CPV-2 and FPV belong to the same viral species, Carnivore protoparvovirus 1, within the family Parvoviridae [6]. FeAstV, species Mamastrovirus 2, belongs to the genus Mamastrovirus within the family Astroviridae and is a non-enveloped, single-stranded positive RNA virus [11]. FeAstV was first reported in 1981 in faeces from diarrheic cats [9], and a novel FeAstV genotype was found in 2012 [11]; however, studies on FeAstV pathogenicity are limited. FBoV was first detected in a stray cat in Hong Kong in 2012 [10] and has been reported in the USA [27], Portugal [17], Japan [22] and China [25]. According to the latest report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), FBoV-1, FBoV-2 and FBoV-3 have been recognized as members of the species Carnivore bocaparvovirus 3, 4, and 5, respectively, within the genus Bocaparvovirus [5], based on the amino acid sequence of the complete NS1 gene [25]. Epidemiological investigations in different countries have suggested that FeAstV and FBoV may cause diarrhea in cats with a prevalence of 4.8%-23.4% [3, 14, 20, 24] and 5.5%-25.9% [10, 22, 25, 27], respectively, and coinfections with FPV, FBoV and FeAstV are also common in cats with diarrhea. Because of the similar clinical symptoms and frequency of coinfections with these three viruses, differentiation of these viruses during clinical diagnosis and epidemiological investigations is difficult.

PCR has become the most widely used method for detection of pathogens due to its high sensitivity and specificity. Routine PCR/RT-PCR methods for detection of FPV, FeAstV and FBoV have been described in previous reports [12, 16], but ??there have been no reports of?? the application of routine PCR for the simultaneous detection and differentiation of these three viruses. Multiplex PCR (mPCR) can simultaneously detect and distinguish two or more target viruses in one reaction, can save time and cost, and has been widely used in large-scale epidemiological investigations [8, 28]. In the present study, a mPCR assay was developed by combining three pairs of universal primers targeting different members of the species Carnivore protoparvovirus 1, FBoV and FeAstV in one reaction. This mPCR assay can be used as an easy and effective method for the detection and differentiation of these three viruses in clinical samples.

Materials and methods

Viruses

The following viruses were used as positive virus controls in the present study: FPV strain JL-03/17-05 (GenBank accession number MF541125), FBoV strain 17CC0302 (GenBank accession number MH155947), and FeAstV strain 17CC0502 (GenBank accession number MH253845). Moreover, feline kobuvirus (FeKoV) strain 16CC0802 (GenBank accession number MH159805), feline calicivirus (FCV) strain CH-JL2 (GenBank accession number KJ495725), feline herpesvirus type 1 (FHV-1) strain CH-B, and standard positive DNA controls of feline coronavirus (FCoV), feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) were used to test the specificity of the mPCR. Different strains identified and maintained in our laboratory, including FPV, CPV 2, CPV 2a, CPV 2b, FBoV 1, FBoV 2, FBoV 3, FeAstV-1 and FeAstV-2, were used to test the ability of the mPCR method to detect a broad spectrum of viruses.

Nucleic acid extraction

Viral nucleic acids were extracted from positive and negative virus controls using an AxyPrepTM Body Viral DNA/RNA Miniprep Kit (Axygen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed for RNA viruses, including FeAstV, FeKoV and FCV, for cDNA synthesis using a PrimerScriptTM RT Reagent Kit (Takara, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleic acids extracted from DNA viruses were used directly as a template for PCR. The clinical samples were prepared using a previously described protocol [26], and nucleic acids were extracted using the above methods.

Primer design

The reference genomic sequences of FPV (FPV, CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c), FBoV (FBoV 1, FBoV 2 and FBoV 3) and FeAstV (FeAstV-1 and FeAstV-2) were obtained from the GenBank nucleotide sequence database from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Highly conserved regions of the same virus were discovered by multiple alignment using the MEGA 7.0 software. Then, three pairs of specific primers based on the conserved regions of these viruses, the VP2 gene of FPV, the NP1 gene of FBoV, and the RdRp gene of FeAstV, were designed for the mPCR assay. Primer Blast and MFE primer software were used to determine the Tm value and specificity of these primer pairs. The nucleotide sequences of the primers are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of the primers used for the multiplex PCR assay

| Target virus | Target gene | Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5’-3’) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPV | VP2 | FPV-F | CATACATGGCAAACAAATAGAGCA | 237 |

| FPV-R | TGTTTTAAATGGCCCTTGTGTAGA | |||

| FBoV | NP1 | FBoV-F | AGAACCRCCRATCACARTCCACT | 465 |

| FBoV-R | TGGCRACCGCYAGCATTTCA | |||

| FeAstV | RdRp | FeAstV-F | GCGGATTGGGCATGGTTTAGA | 645 |

| FeAstV-R | ACCCCTCGTTTGGATCGTTACCT |

Standard plasmid template preparation

Routine PCR was performed for each virus with the corresponding primers in a 25-μl reaction mixture including 12.5 μl of Premix Ex Taq, 0.5 μl each of the forward and reverse primers (10 μM), 2 μl of the nucleic acid extracted from the targeted virus, and 9.5 μl of RNase-free water. The reactions were performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 51 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 30 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The different-sized products of the three viruses, 237 bp for FPV, 465 bp for FBoV and 645 bp for FeAstV, were purified using an AxyPrepTM DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen, China) and ligated to the pMD-18T vector (Takara, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The recombinant plasmids identified as positive were named pMD-FPV, pMD-FBoV and pMD-FeAstV, respectively, and were used to optimize the reaction conditions and determine the sensitivity of the mPCR assay. The plasmid copy number was calculated according to the following formula: copy number (copies/μl) = [6.02 × 1023 × plasmid concentration (ng/μl)]/[plasmid length (bp) × 660].

Optimization of mPCR

The plasmid DNA of the three viruses was serially tenfold diluted to concentrations of 1 × 106 copies/μl, 1 × 105 copies/μl and 1 × 104 copies/μl. Diluted mixtures containing pMD-FPV, pMD-FBoV and pMD-FeAstV at equal concentrations and volumes were used as templates to optimize the reaction mixture and conditions of the mPCR assay, including the concentrations of the primers, dNTP and Ex Taq enzyme; the annealing temperature; and the number of cycles of PCR. Specifically, mPCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl of reaction mixture containing 2 μl of each plasmid DNA, 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 0.25-2 μl of each primer at a concentration of 10 μM, 1-4 μl of the dNTP mix (2.5 mM), 0.3-1 μl of Ex Taq enzyme (5 U/μl) (Takara, China), and RNase-free water to a total volume of 25 μl. The reactions were performed under the following conditions in a thermal cycler: predenaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30-40 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 50-62 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 30 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. A 5-µl sample of the PCR reaction mixture from each test was subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and visualized using a gel documentation system (Wealtec, USA). The optimal reaction conditions were determined based on the presence or absence of primer dimers and the grey-scale value of the electrophoresis band evaluated using Image J software.

Specificity of the mPCR assay

To evaluate the specificity of the mPCR, various combinations of positive virus controls, including a single plasmid DNA, a mixture of two plasmids, and a mixture of three plasmids, were used as templates in the different reactions. The different-sized PCR products were purified and sequenced to confirm the specificity of the mPCR. mPCR was also used to detect other non-targeted viruses, including FeKoV, FCV, FHV-1, FCoV, FIV and FeLV. RNase-free water was used as a negative control.

Sensitivity of the mPCR assay

Tenfold serially diluted recombinant plasmids containing sequences from the three viruses, ranging from 4.04 × 109 copies/μl to 4.04 × 100 copies/μl for FPV, 3.13 × 109 copies/μl to 3.13 × 100 copies/μl for FBoV, and 2.25 × 109 copies/μl to 2.25 × 100 copies/μl for FeAstV, were used to determine the sensitivity of the mPCR. The sensitivity of the routine PCR with only one pair of primers was also tested using tenfold serial dilutions.

Ability of the mPCR assay to detect multiple genotypes

Different genotypes of the three viruses, including FPV, CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b, FBoV-1, FBoV-2, FBoV-3, FeAstV-1 and FeAstV-2, were tested using the mPCR assay to determine the breadth of the specificity of this method.

Application of the mPCR assay on clinical samples

A total of 197 faecal samples collected from domestic cats in northeast China were used to evaluate the performance of mPCR using clinical samples. These clinical samples had been used to investigate the prevalence of FBoV and FeAstV using conventional single PCR in a previous study performed in our laboratory [24, 25]. In the present study, these clinical samples were used to detect FPV using routine PCR as reported previously [23]. The positive rate was calculated for each virus, and the difference in the prevalence of each virus between diarrheic and healthy cats was evaluated by the two-tail chi square test using PASW Statistic 19.0. A probability (p) value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Establishment of the mPCR assay

After optimization, the primers for FPV, FBoV and FeAstV produced amplicons of 237 bp, 465 bp and 645 bp, respectively, with clear target bands on an agarose gel. According to the evaluation method described above, the optimization results were in agreement using different concentrations of the DNA plasmid mixture as templates. The optimal annealing temperature was 51 °C, and the optimal cycle number was 40 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The concentrations of the various reagents in the reaction mixture were also optimized in this study (Supplementary Fig. 2), and the final concentrations were as follows: 2 μl of the dNTP mix (2.5 mM), 0.5 μl of Ex Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl), and 0.5 μl each of the forward and reverse primers (10 μM) for the three viruses.

mPCR specificity

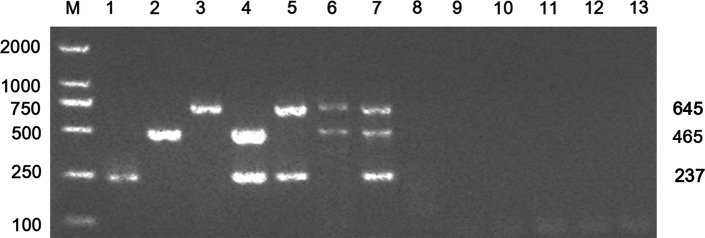

The specificity testing results showed that amplicons of the expected sizes were produced targeting the corresponding virus when different combinations of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV were used as templates in mPCR (Fig. 1). The identity of these amplicons was confirmed by sequencing. No amplification occurred when FeKoV, FCV, FHV-1, FCoV, FIV, FeLV or RNase-free water were used as template in the mPCR. These results indicate that the newly developed mPCR assay was highly specific for the detection and differentiation of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV.

Fig. 1.

Specificity of multiplex PCR for the detection of positive and negative controls using mixed primers. Lanes 1-13: 1, FPV; 2, FBoV; 3, FeAstV; 4, FPV and FBoV; 5, FPV and FeAstV; 6, FBoV and FeAstV; 7, FeAstV, FBoV and FPV; 8, FCV; 9: FHV-1; 10, FCoV; 11, FeLV; 12, FIV; 13, negative control; M, DL2000 DNA marker

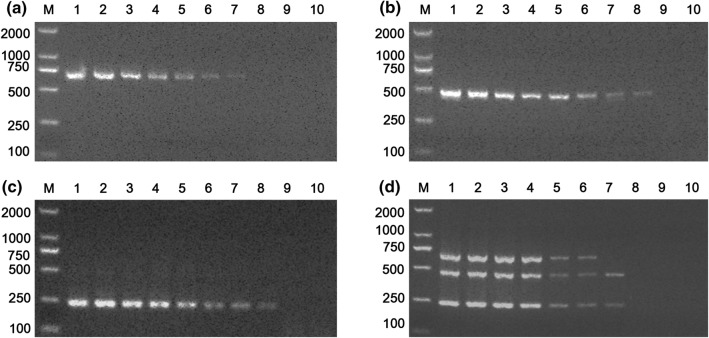

mPCR sensitivity

To determine the sensitivity of the mPCR, plasmid DNA containing sequences from the three viruses was serially diluted tenfold and used as a template for mPCR. The minimum detection limit of mPCR was 4.04 × 103, 3.13 × 103 and 2.25 × 104 viral copies for FPV, FBoV and FeAstV, respectively (Fig. 2d). Moreover, the sensitivity testing results of routine PCR with only one pair of primers showed that the minimum detection limit for FPV, FBoV and FeAstV was 4.04 × 102, 3.13 × 102 and 2.25 × 103 viral copies, respectively (Fig. 2a-c). Taken together, the sensitivity results show that the sensitivity of the mPCR was slightly higher than that of routine PCR.

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity of multiplex PCR and routine PCR for the detection of tenfold serially diluted plasmid DNA from FPV, FBoV and FeAstV. (a, b, c) Routine PCR for FeAstV, FBoV and FPV; (d) mPCR. Lanes 1-10 (a, b and c), FeAstV-, FBoV- and FPV-positive plasmid concentrations ranging from 2.25 × 109 to 2.25 × 100copies/μl, 3.13 × 109 to 3.13 × 100copies/μl and 4.04 × 109 to 4.04 × 100copies/μl. Lanes 1-10 in (d) are reactions performed with tenfold serial dilutions of mixtures of plasmids containing sequences from the three viruses (2.25 × 109 - 2.25 × 100copies/μl, 3.13 × 109 - 3.13 × 100copies/μl, and 4.04 × 109 - 4.04 × 100copies/μl of each virus/sample). M, DL2000 DNA marker

Ability of the mPCR assay to detect multiple genotypes

mPCR was used to detect different genotypes of the three viruses to determine the breadth of the specificity of this method. The results showed that the mPCR was able to detect different genotypes of the target viruses, including FPV, CPV-2, CPV-2a, CPV-2b, FBoV 1, FBoV 2, FBoV 3, FeAstV-1 and FeAstV-2, and amplicons of the expected sizes were obtained (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Evaluation of the mPCR assay using clinical samples

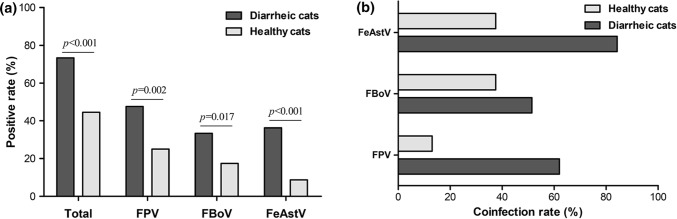

A total of 197 faecal samples that had previously been screened for FBoV and FeAstV were tested using the newly developed mPCR assay and routine PCR targeting FPV, and the test results for mPCR were then compared to those of routine PCR. The results presented in Table 2 indicate that the total detection rate for these three viruses was 59.89% (118/197), of which 73 samples were positive for FPV, 51 were positive for FBoV, and 46 were positive for FeAstV according to the mPCR assay, which was in 100% agreement with the results of the routine PCR assays. The total detection rate of the three viruses in cats with diarrhea (73.33%, 77/105) was significantly higher than that in healthy cats (44.57%, 41/92). Moreover, the detection results showed that the total positive rate for FPV (37.06%, 73/197) was the highest, followed by FBoV (25.89%, 51/197) and FeAstV (23.35%, 46/197), and that the positive rate for each virus in domestic cats with diarrhea was significantly higher than that in healthy cats (47.62% versus 25% for FPV, 33.33% versus 17.39% for FBoV and 36.19% versus 8.69% for FeAstV) (Fig. 3a). Coinfections were frequent, with 34.75% (41/118) of cats shedding more than one of the three viruses.

Table 2.

Screening results for the target virus in 197 faecal samples by multiplex PCR

| Health status | Number of samples | Number of infections with each virus (monoinfection + coinfection) |

Monoinfection | Coinfection | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPV | FBoV | FeAstV | FPV | FBoV | FeAstV | FPV+FBoV | FPV+FeAstV | FBoV+FeAstV | FPV+FBoV+FeAstV | |||

| Diarrhea | 105 |

50 (47.62%) |

35 (33.33%) |

38 (36.19%) |

19 (18.10%) | 17 (16.19%) | 6 (5.71%) |

3 (2.86%) |

17 (16.19%) |

4 (3.81%) |

11 (10.48%) |

77 (73.33%) |

| Health | 92 |

23 (25.00%) |

16 (17.39%) |

8 (8.70%) |

20 (21.74%) | 10 (10.87%) | 5 (5.43%) |

3 (3.26%) |

0 |

3 (3.26%) |

0 |

41 (44.57%) |

| Total | 197 |

73 (37.06%) |

51 (25.89%) |

46 (23.35%) |

39 (19.80%) | 27 (13.71%) | 11 (5.58%) |

6 (3.05%) |

17 (8.63%) |

7 (3.55%) |

11 (5.58%) |

118 (59.89%) |

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV in diarrheic and healthy cats. (a) Total positive rates of these three viruses in diarrheic and healthy cats. The difference was evaluated using the chi-square test. Probability (p) values are shown on the bar chart. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. (b) Monoinfection and coinfection rates of these three viruses in diarrheic and healthy cats

We also analysed the differences in the monoinfection and coinfection rates for each virus between diarrheic and healthy cats (Fig. 3b). The monoinfection rates for FPV (86.95%, 20/23), FBoV (62.5%, 10/16) and FeAstV (62.5%, 5/8) were higher than the coinfection rates in healthy cats. In contrast, cats with diarrhea had higher coinfection rates, with values of 62% (31/50) for FPV, 51.43% (18/35) for FBoV, and 84.22% (32/38) for FeAstV, respectively. Moreover, the coinfection rates of the three viruses in diarrheic cats were significantly higher than those in healthy cats.

Discussion

Viral diarrhea is the most common clinical disease in domestic cats and seriously threatens the life and health of cats. FPV is generally considered in the clinical diagnosis of viral diarrhea in cats, while other viruses are often ignored in clinical testing. Recently, some novel enteric viruses, including FBoV, FeAstV and FeKoV [13], were found in domestic cats, and studies suggest that these viruses are associate with viral diarrhea in cats. Over the last two years, our laboratory has investigated the prevalence of new feline enteric viruses in northeast China and has found that FBoV and FeAstV are widespread in China, with a high prevalence of approximately 25% [24, 25]. Furthermore, coinfections with FPV, FBoV and FeAstV were also found to be frequent in our investigation. However, there is no scientific detection assay to test for the three viruses. Therefore, a multiplex PCR assay that can simultaneously detect and differentiate FPV, FBoV and FeAstV in one reaction was developed and evaluated in the present study.

The competition between two or more pairs of primers in multiplex PCR may affect its specificity and sensitivity, so primer design and selection are critical for the development of multiplex PCR assays. In this study, three pairs of primers targeting highly conserved regions of the genomic sequences of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV were designed to detect different genotypes of the same virus. The primers’ annealing temperature and amplicon length were also evaluated using the online software MFE primer. The primer combination produced amplicons of 237 bp for FPV, 465 bp for FBoV and 645 bp for FeAstV, which were easy to distinguish from one another by electrophoresis using 2.0% agarose gels. Then, a multiple PCR method with this primer combination was established by optimizing the reagent concentration and reaction conditions.

Various common viruses in cats, including FeKoV, FCV, FHV-1, FCoV, FIV and FeLV, were used to evaluate the specificity of the mPCR assay. The testing results showed that no cross-reactions or nonspecific reactions were produced in mPCR with these viruses as templates (Fig. 1), suggesting that this assay had good specificity. Sensitivity testing showed that the minimum detection limit of mPCR was 4.04 × 103 copies/μl, 3.13 × 103copies/μl and 2.25 × 104 copies/μl for FPV, FBoV and FeAstV, respectively, and this was 10-100-fold lower than that of routine PCR (Fig. 2). The low sensitivity was caused by the interaction of primers, as described in previous studies [7, 26]. However, in the detection of clinical samples, the mPCR and routine PCR results were in 100% agreement, suggesting that mPCR was effective.

It has been demonstrated that not only FPV can infect cats but also that the different subtypes of CPV-2 (CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c) can infect domestic cats, causing diarrhea [2]. In addition, in previous studies, FBoV has been classified into three genotypes (FBoV-1, FBoV-2 and FBoV-3) [22] and FeAstV has been classified into different genotypes [24]. In the present study, we designed three pairs of universal primers that can detect the different genotypes of the three viruses. The mPCR was able to detect nucleic acids extracted from different genotypes of the target virus (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting that this method detects a broad spectrum of variants.

Out of the 197 faecal samples tested, 118 were positive for one or more viruses, with a high positive rate of 59.89%. The total positive rates of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV were 37.06% (73/197), 25.89% (51/197) and 23.35% (46/197), respectively, and the positive rates for all three viruses in cats with diarrhea were higher than those in healthy cats, suggesting that FPV, FBoV and FeAstV are associated with viral diarrhea in cats. Moreover, healthy cats had higher monoinfection rates, while cats with diarrhea had higher coinfection rates. Furthermore, coinfections with two or three viruses were frequent, especially in cats with diarrhea [17, 19], with a high positive rate of 34.75% (41/118), consistent with a previous report [24]. The data obtained from the present study confirm that coinfections with various enteric viruses are common in domestic cats.

The lack of identification of other feline diarrhea-associated viruses using the mPCR assay is a limitation of this study. First, in this study, we also tried to develop mPCR for FPV, FBoV, FeAstV, feline coronavirus and feline kobuvirus, but the results were not good. We think that primer competition affects the specificity and sensitivity of mPCR. Second, the epidemiological investigations of feline diarrhea-associated viruses performed in our laboratory suggest that the prevalence of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV is higher in healthy and diarrheic cats and that mixed infections with these three viruses are common in clinical cases. The establishment of this method provides a convenient and advantageous test for epidemiological investigations of these three viruses. However, there are fewer types of viruses involved in epidemiological investigations of feline diarrhea-associated viruses, which is a limitation of this paper. In future studies, we will try to establish an mPCR assay for additional feline diarrhea-associated viruses.

In conclusion, we have developed a multiplex PCR assay that can simultaneously detect and differentiate FPV, FBoV and FeAstV. This multiplex PCR assay is easy, specific, and efficient, and can detect a broad spectrum of different genotypes of these three viruses, thereby providing a good tool for clinical diagnosis or extensive epidemiological investigations of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1 Optimization of the annealing temperature (A) and the number of cycles (B) for multiplex PCR for the detection of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV using mixed primers. (a) Lanes 1-10: 1, 50°C; 2, 51°C; 3, 52°C; 4, 53°C; 5, 55°C; 6, 57°C; 7, 59°C; 8, 60°C; 9, 61°C; 10, 62°C; M, DL2000 DNA marker. (b) Lanes 1-5: 1, 30 cycles; 2, blank; 3, 35 cycles; 4, blank; 5, 40 cycles; M, DL2000 DNA marker (TIFF 4563 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2 Optimization of the reagent concentration for multiplex PCR for the detection of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV using mixed primers. (a) Optimization of the concentration of primers. Lanes 1-6: 1, 0.25 μl; 2, 0.5 μl; 3, 0.75 μl; 4, 1 μl; 5, 1.5 μl; 6, 2 μl; M, DL2000 DNA marker. (b) Optimization of the concentration of the dNTP mixture. Lanes 1-7: 1, 1 μl; 2, 1.5 μl; 3, 2 μl; 4, 2.5 μl; 5, 3 μl; 6, 3.5 μl; 7, 4 μl; M, DL2000 DNA marker. (c) Optimization of the concentration of Ex Taq DNA polymerase. Lanes 1-6: 1, 0.3 μl; 2, 0.4 μl; 3, 0.5 μl; 4, 0.6 μl; 5, 0.8 μl; 6, 1 μl; M, DL2000 DNA marker (TIFF 6527 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 3 Ability of multiplex PCR to detect different genotypes of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV. Lanes 1-10: 1, FPV; 2, CPV-2; 3, CPV-2a; 4, CPV-2b; 5, FBoV-1; 6, FBoV-2; 7, FBoV-3; 8, FeAstV-1; 9, FeAstV-2; 10, Negative control; M, DL2000 DNA marker (TIFF 3397 kb)

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Project of the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (Grant no. 2016YFD0501002). This work was also supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant no. 2017YFD0501703).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments conformed to the guidelines and regulatory requirements established by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin Agricultural University, Jilin Province, China. Owners’ consent was obtained to collect samples from healthy and diarrheic cats.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qian Zhang and Jiangting Niu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Balboni A, Bassi F, De Arcangeli S, Zobba R, Dedola C, Alberti A, Battilani M. Molecular analysis of carnivore Protoparvovirus detected in white blood cells of naturally infected cats. BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:41. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battilani M, Balboni A, Ustulin M, Giunti M, Scagliarini A, Prosperi S. Genetic complexity and multiple infections with more Parvovirus species in naturally infected cats. Vet Res. 2011;42:43. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho YY, Lim SI, Kim YK, Song JY, Lee JB, An DJ. Molecular characterisation and phylogenetic analysis of feline astrovirus in Korean cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2014;16:679–683. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13511812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung JY, Kim SH, Kim YH, Lee MH, Lee KK, Oem JK. Detection and genetic characterization of feline kobuviruses. Virus Genes. 2013;47:559–562. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0953-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotmore SF, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA, Mukha DV, Pintel DJ, Qiu J, Soderlund-Venermo M, Tattersall P, Tijssen P, Gatherer D, Davison AJ. The family Parvoviridae. Arch Virol. 2014;159:1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decaro N, Buonavoglia C. Canine parvovirus—a review of epidemiological and diagnostic aspects, with emphasis on type 2c. Vet Microbiol. 2012;155:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng X, Zhang J, Su J, Liu H, Cong Y, Zhang L, Zhang K, Shi N, Lu R, Yan X. A multiplex PCR method for the simultaneous detection of three viruses associated with canine viral enteric infections. Arch Virol. 2018;163:2133–2138. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3828-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He YP, Zhang Q, Fu MZ, Xu XG. Development of multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection and differentiation of six DNA and RNA viruses from clinical samples of sheep and goats. J Virol Methods. 2017;243:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoshino Y, Zimmer JF, Moise NS, Scott FW. Detection of astroviruses in feces of a cat with diarrhea. Brief report. Arch Virol. 1981;70:373–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01320252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau SK, Woo PC, Yeung HC, Teng JL, Wu Y, Bai R, Fan RY, Chan KH, Yuen KY. Identification and characterization of bocaviruses in cats and dogs reveals a novel feline bocavirus and a novel genetic group of canine bocavirus. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:1573–1582. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.042531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau SK, Woo PC, Yip CC, Bai R, Wu Y, Tse H, Yuen KY. Complete genome sequence of a novel feline astrovirus from a domestic cat in Hong Kong. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00708–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00708-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Liu F, Li Z, Qu L, Liu D. First report of feline bocavirus associated with severe enteritis of cat in Northeast China, 2015. J Vet Med Sci. 2018;80:731–735. doi: 10.1292/jvms.17-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu G, Zhang X, Luo J, Sun Y, Xu H, Huang J, Ou J, Li S. First report and genetic characterization of feline kobuvirus in diarrhoeic cats in China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:1357–1363. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JA, Kennett ML, Rodger SM, Studdert MJ, Thompson WL, Gust ID. Virus and virus-like particles in the faeces of cats with and without diarrhoea. Aust Vet J. 1987;64:100–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1987.tb09638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mende K, Stuetzer B, Sauter-Louis C, Homeier T, Truyen U, Hartmann K. Prevalence of antibodies against feline panleukopenia virus in client-owned cats in Southern Germany. Vet J. 2014;199:419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moschidou P, Martella V, Lorusso E, Desario C, Pinto P, Losurdo M, Catella C, Parisi A, Banyai K, Buonavoglia C. Mixed infection by Feline astrovirus and Feline panleukopenia virus in a domestic cat with gastroenteritis and panleukopenia. J Vet Diagn Investig. 2011;23:581–584. doi: 10.1177/1040638711404149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng TF, Mesquita JR, Nascimento MS, Kondov NO, Wong W, Reuter G, Knowles NJ, Vega E, Esona MD, Deng X, Vinje J, Delwart E. Feline fecal virome reveals novel and prevalent enteric viruses. Vet Microbiol. 2014;171:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niu JT, Yi SS, Hu GX, Guo YB, Zhang S, Dong H, Zhao YL, Wang K. Prevalence and molecular characterization of parvovirus in domestic kittens from Northeast China during 2016–2017. Jpn J Vet Res. 2018;66:145–155. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paris JK, Wills S, Balzer HJ, Shaw DJ, Gunn-Moore DA. Enteropathogen co-infection in UK cats with diarrhoea. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabshin SJ, Levy JK, Tupler T, Tucker SJ, Greiner EC, Leutenegger CM. Enteropathogens identified in cats entering a Florida animal shelter with normal feces or diarrhea. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;241:331–337. doi: 10.2460/javma.241.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuetzer B, Hartmann K. Feline parvovirus infection and associated diseases. Vet J. 2014;201:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takano T, Takadate Y, Doki T, Hohdatsu T. Genetic characterization of feline bocavirus detected in cats in Japan. Arch Virol. 2016;161:2825–2828. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2972-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang S, Wang S, Feng H, Zeng L, Xia Z, Zhang R, Zou X, Wang C, Liu Q, Xia X. Isolation and characterization of feline panleukopenia virus from a diarrheic monkey. Vet Microbiol. 2010;143:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi S, Niu J, Wang H, Dong G, Guo Y, Dong H, Wang K, Hu G. Molecular characterization of feline astrovirus in domestic cats from Northeast China. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0205441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi S, Niu J, Wang H, Dong G, Zhao Y, Dong H, Guo Y, Wang K, Hu G. Detection and genetic characterization of feline bocavirus in Northeast China. Virol J. 2018;15:125. doi: 10.1186/s12985-018-1034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng Z, Liu Z, Wang W, Tang D, Liang H, Liu Z. Establishment and application of a multiplex PCR for rapid and simultaneous detection of six viruses in swine. J Virol Methods. 2014;208:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Li L, Deng X, Kapusinszky B, Pesavento PA, Delwart E. Faecal virome of cats in an animal shelter. J Gen Virol. 2014;95:2553–2564. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.069674-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng X, Liu G, Opriessnig T, Wang Z, Yang Z, Jiang Y. Development and validation of a multiplex conventional PCR assay for simultaneous detection and grouping of porcine bocaviruses. J Virol Methods. 2016;236:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1 Optimization of the annealing temperature (A) and the number of cycles (B) for multiplex PCR for the detection of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV using mixed primers. (a) Lanes 1-10: 1, 50°C; 2, 51°C; 3, 52°C; 4, 53°C; 5, 55°C; 6, 57°C; 7, 59°C; 8, 60°C; 9, 61°C; 10, 62°C; M, DL2000 DNA marker. (b) Lanes 1-5: 1, 30 cycles; 2, blank; 3, 35 cycles; 4, blank; 5, 40 cycles; M, DL2000 DNA marker (TIFF 4563 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2 Optimization of the reagent concentration for multiplex PCR for the detection of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV using mixed primers. (a) Optimization of the concentration of primers. Lanes 1-6: 1, 0.25 μl; 2, 0.5 μl; 3, 0.75 μl; 4, 1 μl; 5, 1.5 μl; 6, 2 μl; M, DL2000 DNA marker. (b) Optimization of the concentration of the dNTP mixture. Lanes 1-7: 1, 1 μl; 2, 1.5 μl; 3, 2 μl; 4, 2.5 μl; 5, 3 μl; 6, 3.5 μl; 7, 4 μl; M, DL2000 DNA marker. (c) Optimization of the concentration of Ex Taq DNA polymerase. Lanes 1-6: 1, 0.3 μl; 2, 0.4 μl; 3, 0.5 μl; 4, 0.6 μl; 5, 0.8 μl; 6, 1 μl; M, DL2000 DNA marker (TIFF 6527 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 3 Ability of multiplex PCR to detect different genotypes of FPV, FBoV and FeAstV. Lanes 1-10: 1, FPV; 2, CPV-2; 3, CPV-2a; 4, CPV-2b; 5, FBoV-1; 6, FBoV-2; 7, FBoV-3; 8, FeAstV-1; 9, FeAstV-2; 10, Negative control; M, DL2000 DNA marker (TIFF 3397 kb)