Abstract

The family Astroviridae consists of two genera, Avastrovirus and Mamastrovirus, whose members are associated with gastroenteritis in avian and mammalian hosts, respectively. We serendipitously identified a novel porcine astrovirus in a fecal specimen from a domestic pig (Sus scrofa domestica) in Hungary. Sequencing of a fragment indicated that it was an ORF1b/ORF2/3′UTR sequence, and it has been submitted to the database as porcine astrovirus type 2 (PAstV-2/Hungary/2007) with accession number GU562296. Its unique sequence characteristics and its phylogenetic position suggest that PAstV-2 could be an important link between previously reported astroviruses and that a genetically divergent lineage of astroviruses exist in piglets.

Keywords: Porcine astrovirus, Domestic pig, Feces, Species

The family Astroviridae consists of small, non-enveloped viruses with a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome, which ranges in size from 6.4 to 7.3 kb. The astrovirus genome has three open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1a encodes the non-structural polyprotein 1a, while the longer ORF1b encodes polyprotein 1ab, which includes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) that is expressed through a ribosomal frameshift at the ORF1a/1b junction. ORF2 encodes the viral capsid structural polyprotein [9].

The family Astroviridae consists of two genera, Mamastastrovirus and Avastrovirus, whose members are known to infect mammalian (humans, cheetahs, calves, pigs, sheep, deer, minks, dogs, kittens, mice) and avian (duck, chickens and turkeys) hosts, respectively. Astroviruses have been reported to cause gastroenteritis in humans and some mammals; however, avian strains have been linked with both intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations [7, 9]. In humans, 8 classical human astrovirus types are known (HAstV1-8); however, novel and diverse groups of human astroviruses have been found recently [3, 8]. Porcine astrovirus was first identified by EM in 1980 [1] and isolated in 1990 [16], and the capsid region (ORF2) was characterized genetically in 2001 [7]. So far, only three porcine astrovirus capsid (ORF2) sequences have been published: two complete capsid sequences from the same source from Japan [7] and one partial capsid sequence from the Czech Republic in 2006 [5].

This study describes the identification and genetic characterization of the ORF1b/ORF2/3′UTR (untranslated) regions of a novel astrovirus from a domestic pig in Hungary.

Fecal samples were collected from 60 healthy piglets (Sus scrofa domestica) aged less than 6 months from a farm located in East Hungary in February 2007 and divided into 4 age groups (<10 days, 3–4 weeks, 3 and 6 months) [12]. The original aim of the study was to detect porcine calicivirus (norovirus and sapovirus) in domestic pigs [13] by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using the generic primer-pairs p289/p290 [6] designed for the calicivirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene (319-nt for norovirus and 331-nt for sapovirus). RNA isolation and RT-PCR were performed as described previously [10]. For the determination of the 3′-end nucleotide sequence of the novel porcine astrovirus by RT-PCR, sequence-specific oligonucleotides were designed on the basis of the conserved regions of reference human and animal astrovirus strains, and the currently available overlapping porcine astrovirus nucleotide sequences (long-range PCR and primer-walking strategy). Fecal samples were also screened for novel porcine astrovirus using sequence-specific primers (pAstV-F, 5′-TGACATTTTGTGGATTTACAGTT and pAstV-R, 5′-CACCCAGGGCTGACCA) amplifying a 799-nt-long ORF1b/ORF2 region at 45°C annealing temperature. PCR products were sequenced directly using a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) with the PCR primers and run on an automated sequencer (ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, Stafford, USA). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA version 4.0 [17]. The 3,625-nucleotide-long ORF1b/ORF2/3′UTR sequence of porcine astrovirus type 2 (PAstV-2) strain Hungary/2007 was submitted to GenBank under accession number GU562296.

Using calicivirus primers p289/p290, 2 (3.3%) of the 60 samples from animals less than 10 days old were positive for porcine sapoviruses. In addition, porcine kobuviruses were serendipitously identified by gel electrophoresis in this sample collection for the first time as non-specific ~1,100-nt-long PCR-products [11, 12]. In another fecal sample (from a 3-month-old pig), an approximately ~720-nt-long weak, non-specific PCR product was also observed. The nucleotide (nt) sequence of this PCR product was determined by direct sequencing, and 67% nt similarity was found to a human astrovirus type 3 (HAstV-3; AF141381) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene in the GenBank database.

The entire 3,625-nt-long continuous sequence of ORF1b (1,046 nt) and ORF2/3′UTR (2,579 nt) of the porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007 was characterized. The putative ORF2 consisted of 2,556 nt (851 aa). The nt and amino acid (aa) distances based on the partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (ORF1b), N-terminal and complete capsid (ORF2) regions between porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007 and the reference astroviruses are shown in Table 1. In the RdRp region (ORF1b), a high degree of nt/aa identity (58–61/61–62%) was found with classical human astroviruses, with highest similarity to HAstV-3 (AF141381). There was no porcine astrovirus RdRp sequence available in the GenBank database for comparison. The characteristic YGDD RdRp motif was encoded by ORF1b. The highly conserved consensus ORF1ab/ORF2 junction and astrovirus promoter sequence UUUGGAGNGGNGGACCNAAN4–8 AUGNC initiating ORF2 (where the ORF2 AUG start codon is underlined; N stands for any of the four nucleotides) are unique in porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007: just before the AUG start codon, this region includes 11 nucleotides (N11) GCATAAGCCTA (compete sequence motif: UUUGGAGGGGCGGACCAAAN11 AUGGC) as the longest known sequence motif among astroviruses. The N-terminal half of the ORF2, with multiple basic Arg (R) residues, was found to be related (33–48% in nt) to other astroviruses, with the highest identity to HAstV-4 (DQ070852). However, the C-terminal half is very different. In the complete ORF2, the highest aa identities (18–19%) were found with porcine, classical human and MLB1 astroviruses. A conserved stem-loop structure that is predicted at the 3′ end of the genomic RNA of members of several astrovirus species was not found in porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007, which also has the shortest (23 nt) 3′UTR reported to date for an astrovirus.

Table 1.

Nucleotide (nt) and amino acid (aa) sequence identity, shown as a percentage or range of percentages (%) based on the partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (ORF1b), N-terminal (782-nt-long) and complete capsid (ORF2) regions of porcine astrovirus type 2 (PAstV-2) strain Hungary/2007 (GU562296) (columns) and reference astroviruses (rows)

| Astrovirus reference strain(s) | Porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007 (GU562296) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1b (partial) nt/aa (%) |

ORF2 (N-terminal) nt/aa (%) |

ORF2 (complete) nt/aa (%) |

|

| Ovine-OAstV (NC_002469) | 55/51 | 41/30 | 28/14 |

| Porcine-PAstV (AB037272) | Not available | 46/43 | 30/19 |

| Human-HAstV 1–5 and 8 (NC_001943; L13745; AF141381; DQ070852; DQ028633; AF260508) | 58–61/61–62 | 46–48/39–40 | 31–32/18–19 |

| Human-HMOAstV (GQ415660) | 56/52 | 46/33 | 31/17 |

| Human-HAstV-MLB1 (FJ222451) | 56/53 | 43/40 | 31/19 |

| Bat-BAstV-1 (EU847155) | 54/51 | 39/31 | 32/17 |

| Mink-MAstV (NC_004579) | 55/53 | 41/32 | 29/16 |

| Avian-AAstV (CAstV: NC_003790); DAstV: NC_012437; TAstV-1: Y15936) | 45–46/37–38 | 33–36/21 | 24–25/10 |

Boldface numbers indicate the highest level of nucleotide and amino acid identity. The porcine astrovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase sequence is not available in GenBank database for comparison

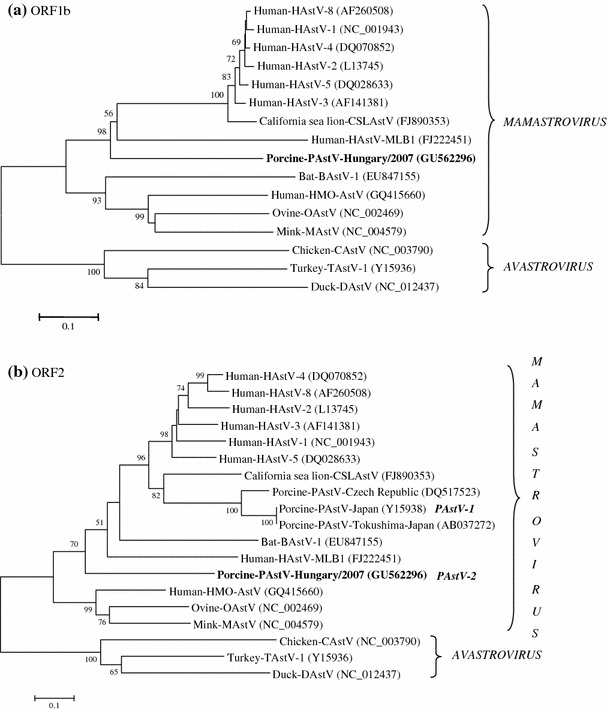

Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007 forms a distinct genetic lineage within the genus Mamastrovirus and is different from the three previously reported porcine astrovirus capsid sequences (Fig. 1). Maintaining the continuity of the current nomenclature, porcine astrovirus strain Hungary/2007 was provisionally named porcine astrovirus type 2 (PAstV-2). PAstV-2 was not detected by RT-PCR from any other fecal samples tested at the farm, using a specific PAstV-2 astrovirus primer pair.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the ORF1b (a) and ORF2 (b) amino acid sequences of porcine astrovirus type 2 (PAstV-2) strain Hungary/2007 (GU562296). A representative of each astrovirus species in the genera Mamastrovirus (mammalian astrovirus) and Avastrovirus (avian astrovirus) were used from GenBank as references. The tree was constructed by using the neighbour-joining method implemented in MEGA4 [17]. The novel porcine astrovirus is indicated by bold letters. Bootstrap values >50% are shown on the branches

In recent studies, novel astroviruses have been identified in humans [3, 8], bats [2], California and Steller sea lions [14] and bottlenose dolphins [14], indicating that astroviruses have a wide range of host species. Interestingly, multiple lineages of astroviruses have been identified in humans (classical HAstV, HAstV-MLB and HMOAstV), phylogenetically separated by different lineages of animal astroviruses [8]. This means that human astroviruses are highly diverse genetically, and potentially, each lineage is likely to represent independent origins [3, 8]. Members of divergent astrovirus lineages can also infect the same animal species, for example, bats [2, 18] and turkeys [4].

Only three porcine astrovirus capsid (ORF2) sequences from domestic pigs have been published [5, 7]. In this study, we detected a potential member of a new species of porcine astrovirus (PAstV-2), indicating that genetically different lineages of astroviruses exist not only in humans but also in piglets. In addition, this is the first report of the nucleotide sequence of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene of any porcine astrovirus. The generic calicivirus primers p289/p290, designed for the calicivirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase region, allowed a porcine astrovirus RdRp sequence to be amplified by RT-PCR. Comparison of primer p289 and the new astrovirus sequence indicates that there is an 11-base-pair-long region of identity between the astrovirus sequence and the 3′-end of the primer sequence. Reverse primer p289, which was designed for the calicivirus (noro- and sapovirus)-conserved RdRp amino acid motif YGDD, recognized the same motif that is also present in astroviruses. Interestingly, porcine kobuvirus was first identified in the same set of fecal specimens [11, 12].

A highly conserved stem-loop-II-like motif was found in the ORF2/3′UTR of mamastroviruses, avastroviruses, equine rhinoviruses, coronaviruses and dog noroviruses [2, 8]. This motif was not recognized in PAstV-2, and it is also absent in turkey astrovirus 2, human astrovirus MLB1 and bat astrovirus AFCD337 [2, 3]. This means that astrovirus screening and typing primers designed for this region [15] are not able to detect these viruses by RT-PCR. Interestingly, ORF2 aa 763–840 of PAstV-2 has 52% positive sequence identity to members of the DnaB-like family of DNA helicases. Its unique sequence characteristics (ORF1b/ORF2 junction, 3′UTR) and phylogenetic position indicate that PAstV-2 might be an important link to other astroviruses.

It has been documented that more than one astrovirus lineage/species may exist in the same host species. The detection and characterization of another novel porcine astrovirus in this study has enabled a better understanding of the heterogeneity and relationships among astroviruses. Constant surveillance is essential to track the association of interspecies transmission or zoonotic infection with astrovirus infections.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA, K83013).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Nucleotide sequence data reported is available in the GenBank database under accession number GU562296.

References

- 1.Bridger JC. Detection by electron microscopy of caliciviruses, astroviruses and rotavirus-like particles in the faeces of piglets with diarrhoea. Vet Rec. 1980;107:532–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu DK, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Novel astroviruses in insectivorous bats. J Virol. 2008;82:9107–9114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00857-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkbeiner SR, Kirkwood CD, Wang D. Complete genome sequence of a highly divergent astrovirus isolated from a child with acute diarrhea. Virol J. 2008;5:117. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu Y, Pan M, Wang X, Xu Y, Xie X, Knowles NJ, Yang H, Zhang D. Complete sequence of a duck astrovirus associated with fatal hepatitis in ducklings. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1104–1108. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.008599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Indik S, Valicek L, Smid B, Dvorakova H, Rodak L. Isolation and partial characterization of a novel porcine astrovirus. Vet Microbiol. 2006;117:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, Huang PW, Zhong WM, Farkas T, Cubitt DW, Matson DO. Design and evaluation of a primer pair that detects both Norwalk- and Sapporo-like caliciviruses by RT-PCR. J Virol Methods. 1999;83:145–154. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonassen CM, Jonassen T, Saif Y, Snodgrass D, Ushijima H, Shimizu M, Grinde B. Comparison of capsid sequences from human and animal astroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1061–1067. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapoor A, Li L, Victoria J, Oderinde B, Mason C, Pandey P, Zaidi SZ, Delwart E. Multiple novel astrovirus species in human stool. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:2965–2972. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014449-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendéz E, Arias CF. Astroviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 981–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reuter G, Krisztalovics K, Vennema H, Koopmans M, Gy Szűcs. Evidence of the etiological predominance of norovirus in gastroenteritis outbreaks––emerging new variant and recombinant noroviruses in Hungary. J Med Virol. 2005;76:598–607. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reuter G, Boldizsár Á, Kiss I, Pankovics P. Candidate new species of Kobuvirus in porcine host. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1968–1970. doi: 10.3201/eid1412.080797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuter G, Boldizsár Á, Pankovics P. Complete nucleotide and amino acid sequences and genetic organization of porcine kobuvirus, a member of a new species in the genus Kobuvirus, family Picornaviridae. Arch Virol. 2009;154:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuter G, Zimšek-Mijovski J, Poljšak-Prijatelj M, Di Bartolo I, Ruggeri FM, Kantala T, Maunula L, Kiss I, Kecskeméti S, Halaihel N, Buesa J, Johnsen C, Hjulsager CK, Larsen LE, Koopmans M, Böttiger B. Incidence, diversity and molecular epidemiology of sapoviruses in swine across Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:363–368. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01279-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera R, Nollens HH, Venn-Watson S, Gulland FM, Wellehan JF. Characterization of phylogenetically diverse astroviruses of marine mammals. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:166–173. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto T, Negishi H, Wang Q-H, Akihara S, Kim B, Nishimura S, Kaneshi K, Nakaya S, Ueda Y, Sugita K, Motohiro T, Nishimura T, Ushijima H. Molecular epidemiology of astroviruses in Japan from 1995 to 1998 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction with serotype-specific primers (1 to 8) J Med Virol. 2000;61:326–331. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200007)61:3<326::AID-JMV7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu M, Shirai J, Narita M, Yamane T. Cytopathic astrovirus isolated from porcine acute gastroenteritis in an established cell line derived from porcine embryonic kidney. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:201–206. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.201-206.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu HC, Chu DK, Liu W, Dong BQ, Zhang SY, Zhang JX, Li LF, Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Chen HL, Poon LLM, Peiris JSM, Guan Y. Detection of diverse astroviruses from bats in China. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:883–887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.007732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]