Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is the major causative agent of fatal diarrhea in piglets. To study the pathogenic features of PEDV using a mouse model, PEDV with virulence in mice is required. In pursuit of this, we adapted a tissue-culture-passed PEDV MK strain to suckling mouse brains. PEDV obtained after ten passages through the brains (MK-p10) had increased virulence for mice, and its fusion activity in cultured cells exceeded that of the original strain. However, the replication kinetics of MK and MK-p10 did not differ from each other in the brain and in cultured cells. The spike (S) protein of MK-p10 had four amino acid substitutions relative to the original strain. One of these (an H-to-R substitution at residue 1,381) was first detected in PEDV isolated after eight passages, and both this virus (MK-p8) and MK-p10 showed enhanced syncytium formation relative to the original MK strain and viruses isolated after two, four, and six passages, suggesting the possibility that the H-to-R mutation was responsible for this activity. This mutation could be also involved in the increased virulence of PEDV observed for MK-p10.

Keywords: Vero Cell, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus, Original Strain, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Introduction

The group I coronavirus porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is an enveloped RNA virus with a single, positive-stranded genome about 30 kb in length [9]. PEDV is the causative agent of pig diarrhea and induces a loss of appetite and weight in adult pigs, whereas it is lethal in piglets [16]. However, our understanding of the pathogenesis of diseases caused by PEDV is limited due to a lack of appropriate small-animal models.

Coronaviruses cause various diseases in a species-specific manner, and they grow in cultured cells established from susceptible host species; human, feline, and porcine coronaviruses grow only in cells isolated from the respective species [24]. One of the major factors determining species specificity is the cellular receptor, which interacts with a given virus, but not with other viruses, when the virus initially encounters cells [5]. Some of the group I coronaviruses, such as porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), utilize aminopeptidase N (APN) [1, 19, 22, 23]. However, the receptor of PEDV has not yet been identified, although there was a controversial report on a PEDV receptor protein [10].

Expression of the receptor protein for mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in cultured cells confers susceptibility to each of these viruses [2, 4, 25]. Expression of the TGEV receptor in mice from a transgene rendered otherwise resistant mice susceptible to TGEV [1]. However, this approach is not available for PEDV. An alternative approach is to isolate viruses that have adapted for growth within the animals and which exhibit virulence. Such adaptations have been reported for two other coronaviruses, IBV and OC43 [3]. In the present study, we isolated a strain of PEDV that was more virulent than the original tissue-culture-adapted virus after passage through mouse brain cells. The adapted virus showed enhanced cytopathology compared with the original virus.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

Vero cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassass, VA, USA). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS). The PEDV strain used in this study was an MK strain isolated from the jejunum of a pig that had exhibited diarrhea in 1996 in Japan, and which had been passed nine times in Vero cell cultures. PEDV was maintained in Vero cells using a slightly modified version of a reported method [8]. Briefly, Vero cells were infected with the virus. After 1 h, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% tryptose phosphate broth (TPB) and 2.5 μg/ml trypsin (Sigma) for 15 h. Next, the cells and supernatant were pooled, ultrasonicated, and stored at −80°C until use.

Virus titration

The PEDV infectious titer was determined by a plaque assay using Vero cells. Briefly, Vero cell monolayers grown in 24-well plates coated with type I collagen (AGC Techno Glass, Chiba, Japan) were inoculated with serially diluted virus samples. After 1 h to allow for adsorption of the virus, the inoculum was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and DMEM containing 10% TPB and 1.25 μg/ml trypsin was added. For titration of the virus, half of the concentration of trypsin was used to drive cell fusion in a procedure that is gentle compared with viral propagation. After a 15-h incubation, the cells were fixed and stained with PBS containing 0.1% crystal violet and 20% formalin under ultraviolet light. After staining for 2 h, the cells were washed with water and dried, and the plaques were counted under a light microscope as described for the infectious titration of human coronavirus 229E [6]. The viral titer in the brains of the mice is given as plaque-forming units (PFU)/50 μl of 10% homogenate, whereas the titer in the supernatant is given as PFU/ml of supernatant; the cell titer is given as PFU/well of a 24-well plate.

Isolation of a murine-adapted variant of PEDV

Specific-pathogen-free (SPF) pregnant ICR mice were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). All animal experiments were approved by the Committee on Experimental Animals, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, and all experimental animals were handled according to the guidelines of the same committee. All SPF mice were confirmed by seromonitoring to be free from infection with MHV, lactate dehydrogenase virus, and other pathogenic microorganisms. Newborn (within 24 h of birth; 0-day-old) mice were used in this study.

PEDV strain MK (2,500 PFU) was inoculated intracerebrally (i.c.) into the brains of 0-day-old mice (n = 12–16). Five days post-infection (p.i.), the mice were sacrificed and their brains collected, pooled, and homogenized in PBS to yield a 10% suspension, which was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Next, 10 μl of the supernatant from the 10% brain homogenate was inoculated i.c. into suckling mouse brains, and the brains were collected as described above. This cycle was repeated ten times, and the virus obtained was designated MK-p10. MK-p10 was amplified once by Vero cell culture to match its condition to that of the original virus, then stored at −80°C until use.

Infection of mice and Vero cell culture

To investigate viral virulence and replication in mouse brains, 0-day-old mice were infected i.c. with 5,000 PFU of PEDV and monitored daily for clinical features; they were also weighed daily. PBS was used in a mock infection. To examine viral replication in the brains, the mice were euthanized on the indicated day p.i., their brains were collected, and 10% homogenates were prepared as described above. To determine the replication kinetics in cultured cells, Vero cells were infected with PEDV at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 0.1. After 1 h, the cells were washed with PBS and cultured in DMEM containing 10% TPB and 2.5 μg/ml trypsin. At the indicated hour p.i., the supernatant and cells were collected separately, the cells were ultrasonicated, and the viral titers were determined using a plaque assay as described above.

Sequence analysis

Viral RNA was extracted with TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Takara-Bio, Shiga, Japan) and oligo-d(T)16 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). To determine the nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding spike (S) protein, the viral sequence containing the S protein region was amplified with Platinum Taq High Fidelity DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and a specific primer set (sense 5′-GTTAGGCTTGTTGAAGAATGG-3′ [nucleotides 20,551–20,571] and anti-sense 5′-AAGACAAGTTGACAGACTTCG-3′ [nucleotides 24,861–24,841]; the nucleotide positions are based on the sequence of CV777 [GenBank NC_003436]). The amplified DNA fragments were purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and then sequenced directly. All sequence analyses were performed with BigDye terminator v3.1 and an ABI PRISM 3130xl (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

To determine the statistical significance of the survival curves, log-rank and generalized Wilcoxon tests were performed. Significance was determined in all other cases using unpaired t tests. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Isolation of a murine-adapted variant of PEDV

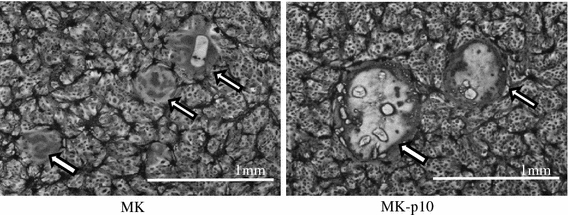

To obtain a murine-adapted variant of PEDV, passage through suckling mice was performed. Zero-day-old mice were inoculated i.c. with the MK strain of PEDV, and the brains of the infected mice were collected four or 5 days later. The brains were pooled and used for the next round of mouse inoculation. Surprisingly, mice infected with the non-adapted, original strain (MK) showed clinical signs and mortality; these observations differ from those reported for HCoV OC43 and IBV [3]. However, in subsequent passages, clinical signs in the infected mice, such as trembling, tremors, and growth retardation, became more obvious. The process was stopped after ten passages, at which point the variant was designated MK-p10. The original MK strain and the mouse-adapted variant MK-p10 were inoculated onto Vero cells in the presence of trypsin and cultured for 15 h. As shown in Fig. 1, more syncytium formation was seen in the cells infected with MK-p10 than in those infected with the original strain. The mean diameter of the MK-p10 syncytia was significantly greater than that of the MK syncytia (874 ± 177 vs. 348 ± 104 μm; n = 10, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

Plaque morphology of the murine-adapted variant of PEDV A Vero cell monolayer was infected with MK and MK-p10. After viral adsorption, the cells were washed with PBS and cultured with DMEM containing 10% TPB and 1.25 μg/ml trypsin for 15 h at 37°C. Next, the cells were fixed, stained with PBS containing 0.1% crystal violet, and observed by light microscopy

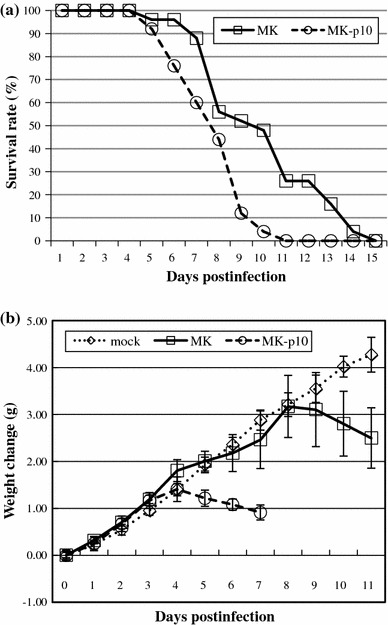

The neurovirulence of MK-p10 in suckling mice was examined. Zero-day-old mice were infected i.c. with 5,000 PFU of virus and monitored daily for clinical symptoms and mortality. All mice infected with MK and MK-p10 succumbed to infection; however, the mice infected with MK-p10 died more quickly than the MK-infected mice (Fig. 2a; n = 25, p < 0.01). The mice were also weighed daily (Fig. 2b; n = 12). The weights of the mice infected with MK or MK-p10 increased for 3–4 days after infection. Subsequently, the weight of the mice decreased beginning 4 days p.i., whereas the mice infected with MK began to lose weight 8 days p.i.—4 days later than the MK-p10-infected mice. The body weight of the mice infected with MK-p10 was determined 7 days p.i. because most of the mice had succumbed by 7–11 days p.i. The mock-infected mice did not exhibit weight loss or clinical symptoms. As described above, a mouse-adapted variant of PEDV was successfully isolated.

Fig. 2.

Virulence of MK-p10 in mice. a Survival rate of MK-p10-infected mice. Zero-day-old mice were infected i.c. with 5,000 PFU of PEDV and monitored daily for mortality (n = 25, p < 0.01; MK, squares; MK-p10, circles). b Body weight changes. Mice infected as described above were weighed daily over the course of the infection (n = 12; mock, diamonds; MK, squares; MK-p10, circles)

Viral growth in mouse brain and cells

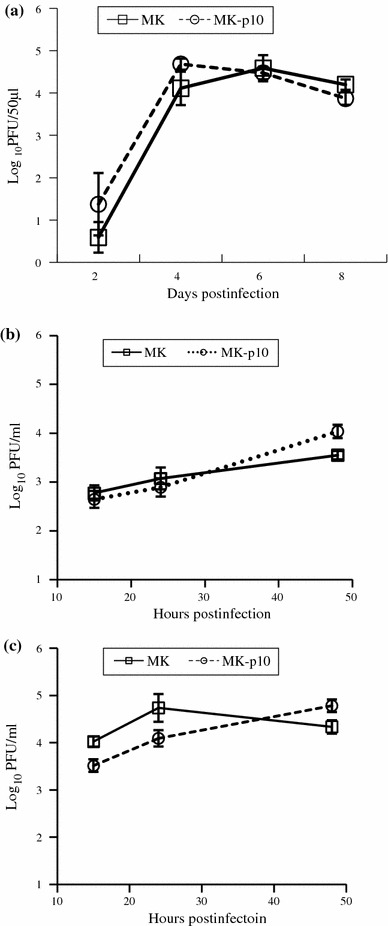

The growth kinetics of the original strain and MK-p10 were examined in suckling mouse brains. MK and MK-p10 exhibited similar growth kinetics in suckling mouse brain, peaking on day 4 p.i. (Fig. 3a). Their growth kinetics in cultured Vero cells was also determined. Some coronaviruses tend to remain intracellular, and viral stocks are prepared by ultrasonication or repeated freeze-thawing cycles. To compare the amounts of budded and intracellular virus, the titers in the supernatant (Fig. 3b) and cells (Fig. 3c) were determined separately. Similar to the growth kinetics in the brains of the mice, the growth pattern in Vero cells did not differ significantly between MK and MK-p10 (Fig. 3b, c). These results suggest that the increased virulence in suckling mice and syncytium formation in cultured cells is not due to increased growth in the brain or cultured cells.

Fig. 3.

The replication kinetics of MK (squares) and MK-p10 (circles). a Viral replication in suckling mouse brain. Zero-day-old mice were infected i.c. with 5,000 PFU of PEDV. At the indicated days p.i., the brains were collected and 10% homogenates were prepared. The viral titer in the brains was determined using a plaque assay with Vero cells and is expressed as PFU/50 μl of 10% homogenates (n = 3). b, c Viral replication in cultured cells. Vero cells were infected with PEDV at an m.o.i. of 0.1. Viral titers in the supernatants (b) and cells (c) were determined separately using plaque assays (n = 6). The viral titer in the supernatant is given as PFU/ml of supernatant, while that in the cells is given as PFU per well of a 24-well plate

Comparison of viral S proteins isolated at different passages

Because the S proteins of coronaviruses are reported to be associated with viral pathogenicity [20], primary sequences of the S proteins of MK-p10 were compared with those of the parental virus MK. Four nucleotide substitutions were observed between the viruses (1,487 [T → C]; 2,321 [C → T]; 2,411 [C → A]; and 4,142 [A → G]), each of which resulted in an amino acid substitution (496 [I → T]; 774 [T → M]; 804 [A → D]; and 1,381 [H → R]) (Table 1). Among these, the amino acid substitutions at positions 804 and 1,381 resulted in a polarity change (hydrophobic to hydrophilic).

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequence and amino acid differences in the S protein region of the murine-adapted variant MK-P10 relative to the S protein of MK

| Nucleotide position | Nucleotide substitution | Amino acid change | Amino acid position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,487 | T → C | Ile (I) → Thr (T) | 496 |

| 2,321 | C → T | Thr (T) → Met (M) | 774 |

| 2,411 | C → A | Ala (A) → Asp (D) | 804 |

| 4,142 | A → G | His (H) → Arg (R) | 1,381 |

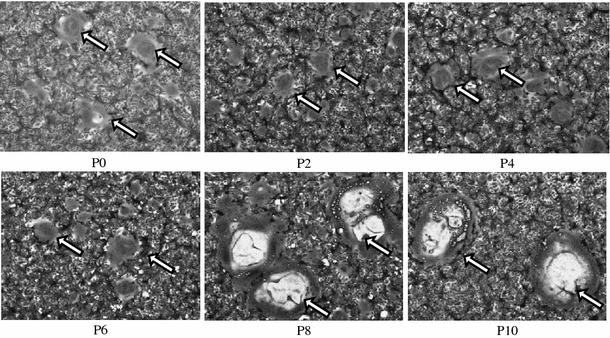

To determine at which brain passage the amino acid changes occurred, we determined the primary sequences of S protein from the viruses isolated after two, four, six, and eight passages in mouse brain. As shown in Table 2, the amino acid at position 804 differed at the second passage, while those at positions 496 and 774 changed simultaneously at the fourth passage. The amino acid change at position 1,381 occurred at the eighth passage. As described above, the plaque size of MK-p10 was larger than that of the parental strain (Fig. 1). This larger plaque morphology was also detected in PEDV after eight passages, whereas the viruses isolated after four and six passages showed syncytium formation similar to that in MK (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the amino acid change at position 1,381 (H to R) first detected at the eighth passage, which is located in the cytoplasmic tail (CT) region, contributed to the larger plaques of MK-p10, though other genes must be considered.

Table 2.

Amino acid changes occurring in the S protein every second passage

| Amino acid position | Passage number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 496 | I | I | T | T | T | T |

| 774 | T | T | M | M | M | M |

| 804 | A | D | D | D | D | D |

| 1,381 | H | H | H | H | R | R |

Fig. 4.

Plaque morphology of PEDV isolates after mouse brain passage PEDV passed in mouse brains two (P2), four (P4), six (P6), eight (P8), or ten (P10) times as well as the original MK (P0) was inoculated onto Vero cells. Cell fusion assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1

Discussion

Two different coronaviruses, OC43 and IBV, have successfully adapted to grow in mice and show virulence after brain-to-brain passage in suckling mice [3, 12]. These viruses initially showed low virulence (i.e., clinical symptoms such as tremor and rigidity and lethargy in suckling mice), but the virulence increased with repeated passage in mouse brains. In this study, the passage of PEDV in suckling mouse brains clearly strengthened its virulence, similar to the adaptation seen in OC43 and IBV. Unexpectedly, the original mouse non-adapted PEDV showed significant virulence for suckling mice. The primary sequences of S protein from the viruses isolated after repeated passages were determined. PEDV passed in mouse brains showed mutations in the S protein, which had accumulated after ten passages. The H-to-R mutation at residue 1,381, which was first detected after eight passages, is likely responsible for the enhanced cell–cell fusion activity, as only those viruses with this mutation showed significantly larger syncytia compared with the original PEDV; The S protein is a major determinant of the fusion activity of coronaviruses [5, 20]. It would be interesting to find out whether this substitution in the S protein is responsible for the enhanced fusion activity by expressing S protein alone. Those mutations found in the mouse-adapted viral S proteins could be responsible for the increased virulence; however, other genes have been reported to be involved in the virulence of such coronaviruses as MHV and SARS-CoV [7, 15, 17, 21]. To identify the genes responsible for the increase in virulence, we would need the entire genomic sequences of the original and mouse-adapted PDEVs; additionally, reverse-genetic analyses would be essential.

PEDV differs from most coronaviruses in that it grows in cultures of cells derived from animal species not susceptible to PEDV; the virus grows efficiently in Vero cells derived from the kidneys of green monkey, which is not a natural host of the virus [8]. Few cases are known in which coronaviruses multiply in cells derived from non-susceptible host animals. SARS-CoV can grow in a variety of cells established from several animal species [13, 14, 18, 24], and it is somewhat capable of growing in the same animals; however, efficient infection is restricted to cells from animals that support SARS-CoV infection [24]. The growth potential of SARS-CoV in a variety of animal cells correlated with the utilization of its receptor molecule, ACE2 [11]. Most known coronaviruses become infective in cells when their functional receptor molecule is expressed by transfection with a plasmid encoding the receptor molecule [5]. This suggests that Vero cells susceptible to PEDV infection express a functional receptor. In our study, both mouse-adapted and non-adapted MK strains of PEDV could infect and grow in suckling mouse brains, suggesting that a receptor molecule utilized by both viruses exists in suckling mouse brain. To determine which cell types in the brain express the receptor, we are attempting to identify the cell types that are infected by PEDV in suckling mouse brain. This will provide valuable information related to the receptor molecule utilized by PEDV.

In summary, a highly neurovirulent variant of PEDV was successfully isolated by passage following the i.c. infection of 0-day-old suckling mice. The S protein of the variant had four amino acid substitutions, which might be responsible for its enhanced cell–cell fusion activity. Of these substitutions, the H-to-R substitution at position 1,381 in the CT region of the S protein is likely to be the determinant of the high fusion activity. To address this possibility, the expression of wild-type and mutant S proteins in cultured cells and an analysis of their fusion activity are necessary. Reverse-genetic analyses of the entire PEDV genome are also required to assess the effect of S protein mutations on the virulence and pathogenesis of PEDV.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shutoku Matsuyama, Miyuki Kawase, and Makoto Ujike for their valuable comments and encouragement. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B; No. 19390135) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Abbreviations

- APN

Aminopeptidase N

- CT

Cytoplasmic tail

- FCS

Fetal calf serum

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- HCoV

Human coronavirus

- IBV

Infectious bronchitis virus

- i.c.

Intracerebrally

- MHV

Mouse hepatitis virus

- m.o.i.

Multiplicity of infection

- PEDV

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PFU

Plaque-forming unit

- p.i.

Post-infection

- S

Spike

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- TGEV

Transmissible gastroenteritis virus

- TPB

Tryptose phosphate broth

References

- 1.Delmas B, Gelfi J, L’Haridon R, Vogel LK, Sjostrom H, Noren O, Laude H. Aminopeptidase N is a major receptor for the entero-pathogenic coronavirus TGEV. Nature. 1992;357:417–420. doi: 10.1038/357417a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dveksler GS, Pensiero MN, Cardellichio CB, Williams RK, Jiang GS, Holmes KV, Dieffenbach CW. Cloning of the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) receptor: expression in human and hamster cell lines confers susceptibility to MHV. J Virol. 1991;65:6881–6891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6881-6891.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirai K, Yagami K, Shimakura S, Hirano N, Taguchi F, Suzuki Y. Growth of infectious bronchitis virus in suckling mice brain. Res Bull Fac Gifu Univ. 1976;39:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofmann H, Geier M, Marzi A, Krumbiegel M, Peipp M, Fey GH, Gramberg T, Pohlmann S. Susceptibility to SARS coronavirus S protein-driven infection correlates with expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and infection can be blocked by soluble receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes KV, Compton SR. Coronavirus receptors. In: Siddell SG, editor. The Coronaviridae. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawase M, Shirato K, Matsuyama S, Taguchi F. Protease-mediated entry via the endosome of human coronavirus 229E. J Virol. 2009;83:712–721. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01933-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Martinez-Sobrido L, Frieman M, Baric RA, Palese P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and nucleocapsid proteins function as interferon antagonists. J Virol. 2007;81:548–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusanagi K, Kuwahara H, Katoh T, Nunoya T, Ishikawa Y, Samejima T, Tajima M. Isolation and serial propagation of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in cell cultures and partial characterization of the isolate. J Vet Med Sci. 1992;54:313–318. doi: 10.1292/jvms.54.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai MM, Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li BX, Ge JW, Li YJ. Porcine aminopeptidase N is a functional receptor for the PEDV coronavirus. Virology. 2007;365:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, Choe H, Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntosh K, Becker WB, Chanock RM. Growth in suckling-mouse brain of “IBV-like” viruses from patients with upper respiratory tract disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:2268–2273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.6.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagata N, Iwata N, Hasegawa H, Sato Y, Morikawa S, Saijo M, Itamura S, Saito T, Ami Y, Odagiri T, Tashiro M, Sata T. Pathology and virus dispersion in cynomolgus monkeys experimentally infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus via different inoculation routes. Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88:403–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagata N, Iwata N, Hasegawa H, Fukushi S, Harashima A, Sato Y, Saijo M, Taguchi F, Morikawa S, Sata T. Mouse-passaged severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus leads to lethal pulmonary edema and diffuse alveolar damage in adult but not young mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1625–1637. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ontiveros E, Kuo L, Masters PS, Perlman S. Inactivation of expression of gene 4 of mouse hepatitis virus strain JHM does not affect virulence in the murine CNS. Virology. 2001;289:230–238. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pensaert MB, de Bouck P. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch Virol. 1978;58:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfefferle S, Krahling V, Ditt V, Grywna K, Muhlberger E, Drosten C. Reverse genetic characterization of the natural genomic deletion in SARS-Coronavirus strain Frankfurt-1 open reading frame 7b reveals an attenuating function of the 7b protein in vitro and in vivo. Virol J. 2009;6:131. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts A, Vogel L, Guarner J, Hayes N, Murphy B, Zaki S, Subbarao K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of golden Syrian hamsters. J Virol. 2005;79:503–511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.503-511.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaguchi AY, Shows TB. Coronavirus 229E susceptibility in man-mouse hybrids is located on human chromosome 15. Somatic Cell Genet. 1982;8:83–94. doi: 10.1007/BF01538652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spaan W, Cavanagh D, Horzinek MC. Coronaviruses: structure and genome expression. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(Pt 12):2939–2952. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-12-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sperry SM, Kazi L, Graham RL, Baric RS, Weiss SR, Denison MR. Single-amino-acid substitutions in open reading frame (ORF) 1b-nsp14 and ORF 2a proteins of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus are attenuating in mice. J Virol. 2005;79:3391–3400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3391-3400.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tresnan DB, Levis R, Holmes KV. Feline aminopeptidase N serves as a receptor for feline, canine, porcine, and human coronaviruses in serogroup I. J Virol. 1996;70:8669–8674. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8669-8674.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tresnan DB, Holmes KV. Feline aminopeptidase N is a receptor for all group I coronaviruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;440:69–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss SR, Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams RK, Jiang GS, Holmes KV. Receptor for mouse hepatitis virus is a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen family of glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5533–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]