Abstract

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting rabies virus (RV) glycoprotein (G) and nucleoprotein (N) genes were evaluated as antiviral agents against rabies virus in vitro in BHK-21 cells. To select effective siRNAs targeting RV-G, a plasmid-based transient co-transfection approach was used. In this, siRNAs were expressed as short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), and their ability to inhibit RV-G gene expression was evaluated in cells transfected with a plasmid expressing RV-G. The nine different siRNAs designed to target RV-G exhibited varying degrees of knockdown of RV-G gene expression. One siRNA (si-G7) with considerable effect in knockdown of RV-G expression also demonstrated significant inhibition of RV multiplication in BHK-21 cells after in vitro challenge with the RV Pasteur virus-11 (PV-11) strain. A decrease in the number of fluorescent foci in siRNA-treated cells and a reduction (86.8 %) in the release of RV into infected cell culture supernatant indicated the anti-rabies potential of siRNA. Similarly, treatment with one siRNA targeting RV-N resulted in a decrease in the number of fluorescent foci and a reduction (85.9 %) in the release of RV. As a dual gene silencing approach where siRNAs targeting RV-G and RV-N genes were expressed from single construct, the anti-rabies-virus effect was observed as an 87.4 % reduction in the release of RV. These results demonstrate that siRNAs targeting RV-G and N, both in single and dual form, have potential as antiviral agent against rabies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00705-013-1738-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rabies, Rabies Virus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Hepatitis Delta Virus, Fluorescent Focus

Introduction

Rabies is a fatal zoonotic disease caused by virus belonging to the genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae, order Mononegavirales. In addition to its victims among domestic and wild animals, the disease is responsible for 50,000-55,000 human deaths per year in Asia and Africa [1]. Rabies virus (RV), after infection inside the body, enters to the central nervous system, leading to acute encephalomyelitis. Once the clinical symptoms specific to disease are initiated, the chances for survival are very poor. Pre- and post-exposure vaccinations are the most efficient and highly recommended methods for the prevention of disease in human as well as in animals [1, 2]. Sometimes, due to unnoticed exposure or vaccination failure, disease is diagnosed after the onset of clinical symptoms, and death becomes unavoidable due to the unavailability of any effective line of treatment. Considering the fatal nature of clinical rabies, efforts are being made to develop a post-exposure treatment strategy that could inhibit the multiplication of virus inside the cell and the spread of infection to uninfected nervous cells without damaging them. A recently discovered endogenous mechanism called ‘RNA interference (RNAi)’ has been used in the past decade to inhibit virus multiplication through potent and efficient sequence-specific gene targeting.

First described in 1998, RNAi mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) in a sequence-dependent manner through short (~21-23 nucleotides long) RNA molecules called small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). siRNA, along with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) forms an activated complex that specifically recognises and binds to complementary mRNA. The mRNA is then cleaved into smaller fragments, inactivating its expression [3]. This mechanism of gene silencing is highly conserved in plants, fungi, worms, insects and mammals [see refs. 4–6 for review]. Along with inhibition of gene expression, the endogenous cellular mechanism of RNAi performs multiple biological functions such as mediating the cellular response to viral infections, controlling the mobility of transposable genetic elements, and regulation of gene expression during animal development [see ref. 7 for review]. RNAi-based gene silencing of target genes has generated ample opportunities for therapeutic applications against various diseases and disorders. In the process of development of antiviral therapeutics, sequence-specific knockdown of viral genes that are indispensable for replication and pathogenesis has generated special interest. RNAi-based antiviral strategies have been developed for many RNA and DNA viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus, poliovirus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human papilloma virus, dengue virus, hepatitis delta virus, murine gamma herpesviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus [see ref. 8 for review].

Recent investigations have shown that inhibition of RV multiplication can be achieved through RNAi targeting of the RV nucleoprotein (N) gene [9–15] both in vitro and in vivo. Silencing of other RV genes, such as the phosphoprotein (P) [11] and polymerase (L) genes [12], has also resulted in some degree of anti-rabies effect. These results suggest that targeting single RV gene might not be sufficient to achieve absolute inhibition of RV multiplication. Another RV gene, the glycoprotein (G) gene, which has a crucial role in pathogenesis by controlling the rate of virus uptake into cells, trans-synaptic virus spread and virus replication during infection [16–19], could be a target for RNAi against rabies. To our knowledge, there is no published report on evaluation of siRNAs targeting the RV-G gene till now. However, siRNA targeting the G genes of other viruses of the family Rhabdoviridae has been evaluated for inhibition of virus multiplication [20, 21].

In the present study, siRNAs targeting RV-G were designed and evaluated for inhibition of RV multiplication in vitro in BHK-21 cells. Furthermore, as a dual gene silencing approach, an siRNA with a considerable effect against RV-G was evaluated in combination with an siRNA targeting the RV-N gene for its anti-rabies-virus effect in vitro in BHK-21 cells.

Materials and methods

Cells and virus

Baby hamster kidney-21 (BHK-21) and human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK-293) cell lines were procured from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India, and grown at 37 °C under 5 % CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified minimum essential medium (DMEM, Hyclone), supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Hyclone).

The mouse-brain-adapted rabies challenge virus standard 11 (CVS-11) strain was used to amplify RV genes by RT-PCR. The RV Pasteur virus 11 (PV-11) strain, adapted to BHK-21 cells, was used for in vitro challenge in BHK-21 cells.

Construction of RV target gene reporter plasmids

The target gene reporter plasmids pDsRed-G and pDsRed-N were constructed for expressing the RV-G and RV-N proteins, respectively, with a red fluorescent protein (RFP) fusion at the C-terminal end. For construction of pDsRed-G, a 1572-bp full-length RV-G gene was amplified by RT-PCR with primers (Table 1), using cDNA prepared from total RNA isolated using RV-CVS-11-infected mouse brain and cloned in the pDsRed-N1 vector (Clontech) between in NheI and BamHI sites. Similarly, pDsRed-N was constructed by amplifying the 1380-bp full-length RV-N gene by RT-PCR using primers (Table 1) and cloned in the pDsRed-N1 vector between HindIII and BamHI sites.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of different primers used in the study. The restriction endonuclease sites are underlined

| Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| RV-G-RFP-F | AAAGCTAGCATGGTTCCTCAGGTTCTTTTG |

| RV-G-RFP-L | AAAGGATCCAGTCTGGTCTCACCTCCACT |

| RV-N-RFP-F | ACAAAGCTTAATGGATGCCGACAAGATTGT |

| RV-N-RFP-L | CAAGGATCCCATGAGTCACTCGAATATGTCTT |

| RFP-RT-F | CCCCGTAATGCAGAAGAAGA |

| RFP-RT-R | GGTGATGTCCAGCTTGGAGT |

| GAPDH-RT-F | CATGTTTGTGATGGGCGTGAACCA |

| GAPDH-RT-R | TAAGTCCCTCCACGATGCCAAAGT |

Construction of single and dual small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) expression plasmids

siRNA sequences targeting a conserved region of the RV-G gene (GenBank accession no. AJ506997) were designed using different algorithms available online from IDT, Dharmacon, siDirect, Whitehead Institute, GeneScript and Invitrogen and selected on the basis of sequence motif and thermodynamics guidelines [22]. Each siRNA candidate sequence was compared to a unique and comprehensive EST/mRNA collection from humans and mice using BLAST to avoid possible unwanted off-target effects. Nine siRNA sequences targeting the RV-G gene were selected for the study (Table 2). One siRNA targeting the RV-N gene, reported earlier, was included in this study [11]. All siRNA target sequences were synthesized as sense and antisense oligonucleotides along with restriction endonuclease cohesive ends (Table 3), annealed and cloned as shRNA into an siRNA plasmid expression vector (psi-C) between BamHI and XhoI, sites under the control of a U6 promoter. One scrambled siRNA with no homology to the RV genome was cloned as a negative control siRNA. The recombinant plasmids, named, psi-G1 to 9, psi-N and psi-C, were characterized by restriction endonuclease analysis and nucleotide sequencing.

Table 2.

siRNA sequences and their target locations in the target RV glycoprotein mRNA

| siRNA name | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA-G1 | Target (sense)- GAC CAC CAA GTC AGT AAG TTT | 930-950 |

| siRNA (antisense)-AAA CTT ACT GAC TTG GTG GTC | ||

| siRNA-G2 | Target (sense)- CGG AAA GTG CTC AGG AAT A | 525-543 |

| siRNA (antisense)-TAT TCC TGA GCA CTT TCC G | ||

| siRNA-G3 | Target (sense)- GTA TAA GTC TCT AAA AGG AGC | 702-722 |

| siRNA (antisense)-GCT CCT TTT AGA GAC TTA TAC | ||

| siRNA-G4 | Target (sense)- CTC AAA AGG GTG TTT GAA AGT | 1077-1097 |

| siRNA (antisense)-ACT TTC AAA CAC CCT TTT GAG | ||

| siRNA-G5 | Target (sense)- CCT TCA TGG GAA TCA TAT AAG | 1531-1551 |

| siRNA (antisense)-CTT ATA TGA TTC CCA TGA AGG | ||

| siRNA-G6 | Target (sense)- GAG GCC TGT ATA AGT CTC TAA | 695-715 |

| siRNA (antisense)-TTA GAG ACT TAT ACA GGC CTC | ||

| siRNA-G7 | Target (sense)- AAG TCA GTA AGT TTC AGA CGT | 937-957 |

| siRNA (antisense)-ACG TCT GAA ACT TAC TGA CTT | ||

| siRNA-G8 | Target (sense)- GGT GTT TTT CAA TGG TTT A | 1128-1146 |

| siRNA (antisense)-TAA ACC ATT GAA AAA CAC C | ||

| siRNA-G9 | Target (sense)- CCA TCT CAG CTG TCC AAA T | 117-135 |

| siRNA (antisense)-ATT TGG ACA GCT GAG ATG G |

Table 3.

Schematic diagram showing annealed sense and antisense oligonucleotides along with restriction enzyme sites used for cloning into the shRNA expression vector. The siRNA sequences are underlined

| Name | BamHI | Anti-sense strand | Loop | Sense strand | RNA PolIII terminator | XhoI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shRNA-G1 |

5′-GATCCCAAACTTACTGACTTGGTGGTC TTGATATCCGGACCACCAAGTCAGTAAGTTTTTTTTTCCAA C-3′ 3′-GGTTTGAATGACTGAACCACCAGAACTATAGGCCTGGTGGTTCAGTCATTCAAAAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G2 |

5′-GATCCCTATTCCTGAGCACTTTCCG TTGATATCCGCGGAAAGTGCTCAGGAATATTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGATAAGGACTCGTGAAAGGCAACTATAGGCGCCTTTCACGAGTCCTTATAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G3 |

5′-GATCCCGCTCCTTTTAGAGACTTATAC TTGATATCCGGTATAAGTCTCTAAAAGGAGCTTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGCGAGGAAAATCTCTGAATATGAACTATAGGCCATATTCAGAGATTTTCCTCGAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G4 |

5′-GATCCCACTTTCAAACACCCTTTTGAG TTGATATCCGCTCAAAAGGGTGTTTGAAAGT TTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGTGAAAGTTTGTGGGAAAACTCAACTATAGGCGAGTTTTCCCACAAACTTTCAAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G5 |

5′-GATCCCGCTTATATGATTCCCATGAAGG TTGATATCCGCCTTCATGGGAATCATATAAGTTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGCGAATATACTAAGGGTACTTCCAACTATAGGCGGAAGTACCCTTAGTATATTCAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G6 |

5′-GATCCCGTTAGAGACTTATACAGGCCTC TTGATATCCGGAGGCCTGTATAAGTCTCTAA TTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGCAATCTCTGAATATGTCCGGAGAACTATAGGCCTCCGGACATATTCAGAGATTAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G7 |

5′-GATCCCACGTCTGAAACTTACTGACTT TTGATATCCGAAGTCAGTAAGTTTCAGACGTTTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGTGCAGACTTTGAATGACTGAAAACTATAGGCTTCAGTCATTCAAAGTCTGCAAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G8 |

5′-GATCCCGTAAACCATTGAAAAACACC TTGATATCCGGGTGTTTTTCAATGGTTTATTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGCATTTGGTAACTTTTTGTGGAACTATAGGCCCACAAAAAGTTACCAAATAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-G9 |

5′-GATCCCATTTGGACAGCTGAGATGG TTGATATCCGCCATCTCAGCTGTCCAAATTTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGTAAACCTGTCGACTCTACCAACTATAGGCGGTAGAGTCGACAGGTTTAAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-N |

5′-GATCCCGTAAAGATGCATGTTCAGAGAC TTGATATCCGGTCTCTGAACATGCATCTTTATTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGCATTTCTACGTACAAGTCTCTGAACTATAGGCCAGAGACTTGTACGTAGAAATAAAAAAGGTTGAGCT-5′ |

|||||

| shRNA-C |

5′-GATCCCCGTTAAACTGACTCAAGCGCC TTGATATCCGGGCGCTTGAGTCAGTTTAACGTTTTTTCCAAC-3′ 3′-GGGCAATTTGACTGAGTTCGCGGAACTATAGGCCCGCGAACTCAGTCAAATTGCAAAAAAGGTTGAACT-5′ |

|||||

For construction of a dual-gene-targeting siRNA expression plasmid, the most efficient siRNAs targeting RV-G (si-G7) and RV-N (si-N) were selected. The siRNA expression cassette targeting the RV-N gene was isolated from the psi-N plasmid with NotI (blunt) and XbaI cohesive ends and cloned into the psi-G7 plasmid into XhoI (blunt) and XbaI sites. The resultant plasmid (psi-G7N) consisted of two siRNAs expression cassettes expressing siRNAs against both the RV-G and RV-N genes. The psi-G7N plasmid was characterized by restriction endonuclease analysis and nucleotide sequencing.

Co-transfection of RV target gene reporter and siRNAs expression plasmids

To select siRNAs effectively targeting RV-G or N mRNAs, HEK-293 cells were transiently co-transfected at a 1:2 ratio with target reporter gene plasmid encoding either RV-G or N fused with red fluorescent protein (RFP) and silencing plasmid encoding gene-specific siRNAs (psi-G1 to 9) or psi-N or negative control siRNA (psi-C). HEK-293 cells were grown to 80-90 % confluence in a 24-well plate and co-transfected using Lipofectomine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). At 48 h post-transfection, the transfected cells were analyzed for RFP expression using an Olympus IX51 fluorescent microscope with an UMNG2 (RFP) filter.

The efficiency of the dual-gene-targeting siRNA expression plasmid (psi-G7N) was evaluated using a transient plasmid co-transfection method against RV-G and N gene transcripts. Briefly, HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with psi-G7N plasmid and either the RV-G target gene expression plasmid (pDsRed-G) or the RV-N target gene expression plasmid (pDsRed-N) and analysed for RFP expression at 48 h post-transfection. The single-gene-targeting siRNA expression plasmids (psi-G7 or psi-N) and control siRNA expression plasmid (psi-C) were included as controls.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR

For quantitative estimation of the amount of RV-G mRNA in co-transfected HEK-293 cells, real-time PCR was performed. Briefly, the total RNAs were isolated using Trizol LS reagent (Invitrogen) from HEK-293 cells co-transfected with different siRNAs expressing plasmids and target gene reporter plasmid at 48 h post-transfection, and gene transcripts in the total RNA preparation were reverse transcribed into cDNAs using an oligo dT primer and RevertAid M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas) following manufacturer’s protocol. The RV-G-RFP gene transcripts in 1:10-diluted cDNAs were quantified using gene-specific real-time primers (Table 1) using a KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The percent reduction in RV-G gene transcript levels in siRNAs targeting RV-G treated cells compared to control was determined after normalization with GAPDH gene transcripts following the method described earlier [23].

Rabies virus infection of BHK-21 cells and titration

The efficiency with which different siRNAs inhibited RV multiplication was evaluated in vitro by transfection of BHK-21 cells with siRNA-expressing plasmids and challenge with a BHK-21-adapted RV PV-11 strain. Briefly, BHK-21 cells were grown to 80-90 % confluence in a 24-well plate and transfected using Lipofectomine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) with different siRNA-expressing plasmids and infected with RV PV-11 at an MOI of 0.01. At 48 h postinfection, the infected cell culture supernatant was harvested and stored at −80 °C for virus titer determination. The infected cell monolayer was fixed with 80 % acetone, and RV in infected cells was detected by direct fluorescent antibody staining using an FITC-labeled antibody against rabies virus nucleocapsid (BioRad) using the method of the OIE for the fluorescent focus unit (ffu) assay [24]. Cell nuclei were counterstained with Prolong gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen).

The RV titer in infected cell culture supernatant harvested at 48 h postinfection was determined by ffu assay. Briefly, serial tenfold dilutions of virus supernatant were mixed with 1 × 104 BHK-21 cells in a flat-bottom 96-well plate in triplicate and incubated at 37 °C. Two days after infection, infected cells were fixed with 80 % acetone, and plaques were visualized after staining with an FITC-labeled antibody against the rabies virus nucleocapsid, and the ffu titer was determined.

Results

Silencing effect of siRNAs targeting the RV-G gene

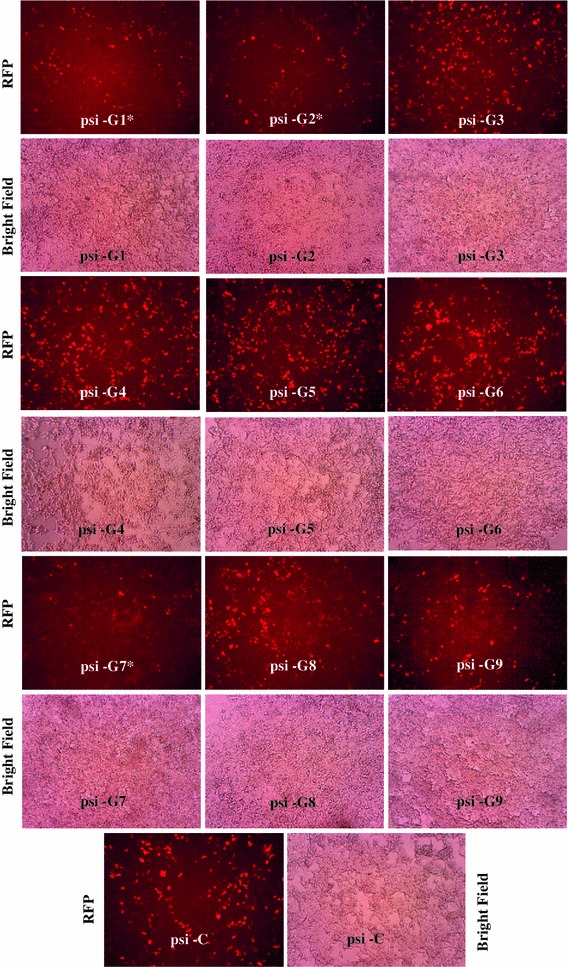

To evaluate the silencing effect of siRNAs targeting the RV-G gene, HEK-293 cells were transiently co-transfected with nine different siRNA expression plasmids (psi-G1 to 9) and target gene reporter plasmids (pDsRed-G). The RFP-tagged version of the RV-G fusion protein was detected in all transfected cells (Fig. 1). However, cells containing the RV-G gene targeting siRNAs showed a silencing effect as reduction in red fluorescence (indicating reduction in target gene expression) compared to control (co-transfected with negative control siRNA). This confirmed that there was expression of siRNA, which effectively silenced the target RV-G gene in a gene-specific manner. Three siRNA expression plasmids, named psi-G1, psi-G2 and psi-G7, expressing siRNAs targeting the RV-G gene, were effective in knockdown of RV-G-RFP fusion protein expression compared to other siRNAs, including control siRNA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of different siRNAs targeting the RV-G gene using a plasmid co-transfection approach in HEK-293 cells. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with different RV-G gene silencing constructs expressing different siRNAs (si-G1 to 9) or control siRNA (si-C) along with a target gene reporter plasmid (pDsRed-G) at a 1:2 ratio. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were analysed for red fluorescence. A reduction in red fluorescence compared with the control indicated a reduction in expression of the RV-G-RFP protein. Magnification, 100X. “*” indicates siRNAs (psi-G1, G2 and G7) with marked reduction in expression of RV-G-RFP protein

For quantitative evaluation of siRNAs, levels of RV-G-RFP transcripts in different co-transfected HEK-293 cells were quantified by real-time PCR. The levels of RV-G-RFP transcripts in three independent experiments demonstrated that one siRNA (si-G7) could efficiently knock down the RV-G transcripts. The greatest reduction in the amount of RV-G-RFP transcript (64.5 ± 1.3 %) was observed with psi-G7; however, the effect was less pronounced with psi-G1 (38.3 ± 1.4 %) and psi-G2 (46.5 ± 1.7 %) (Supplementary Fig. 1). This indicated that all the three siRNAs (si-G1, si-G2 and si-G7) were effective in reducing the levels of target RV-G transcripts (RV-G-RFP); however, the knockdown effect was stronger with si-G7.

To assess the effectiveness of siRNAs expressed by plasmids to inhibit RV multiplication, BHK-21 cells were transfected with siRNA-expressing plasmids and challenged with the RV-PV-11 strain. The presence of RV after fluorescent focus staining revealed that the reduction in RV multiplication was higher with psi-G7 than with the other siRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 2). To estimate the inhibitory effect of siRNAs more precisely, their ability to limit infectious virus production was analyzed by determining the RV ffu count in infected cell culture supernatant. The psi-G1-, psi-G2- and psi-G7-treated BHK-21 cells showed RV titers of 8.3 ± 0.8 × 102, 5.6 ± 0.8 × 102 and 4.6 ± 0.8 × 102 ffu/ml of RV, respectively. These results are the average of four independent experiments. Collectively, there was an 86.8 ± 8.8 % reduction in RV ffu count with siRNA si-G7, while the reduction was 74.7 ± 10.5 % and 78.7 ± 6.9 % with the siRNAs si-G1 and si-G2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3).

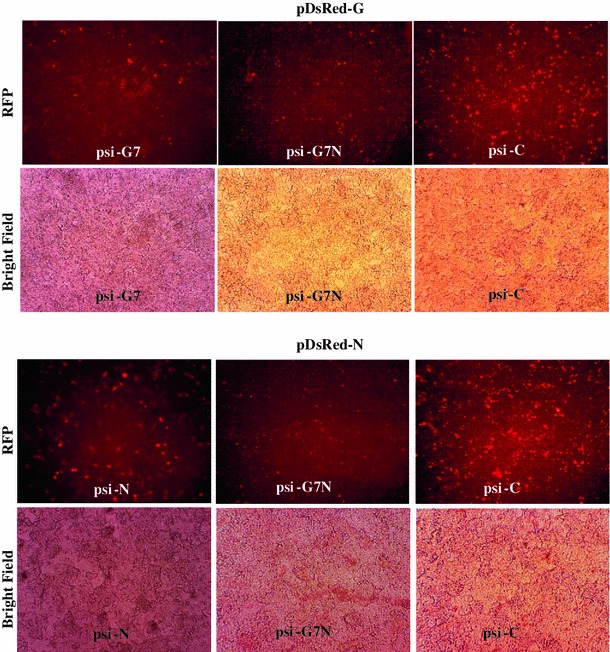

Silencing effect of a dual-gene-targeting siRNAs expression plasmid

The dual-gene-targeting siRNA expression plasmid (psi-G7N) expressing si-G7 and si-N siRNAs targeting the RV-G and N genes, respectively, was analysed for its gene silencing effect and compared with single-gene-targeting siRNA (psi-G or psi-N) and control siRNA (psi-C). The reduction in red fluorescence with cells transfected with psi-G7N compared to cells transfected with psi-G, psi-N or psi-C indicated that psi-G7N, expressing dual siRNAs (si-G7 and si-N), was able to decrease the expression of both the target genes (RV-G and N) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of single and dual gene silencing constructs expressing siRNAs targeting the RV-G and N genes to inhibit expression of the RV-G or N genes, using a plasmid co-transfection approach in HEK-293 cells. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected at a 1:2 ratio with dual (psi-G7N) or single (psi-G7 or psi-N) gene silencing construct expressing siRNAs or control siRNA (psi-C) along with target gene reporter plasmids (pDsRed-G or pDsRed-N) expressing RV-G or N with C-terminal fusion with red fluorescent protein (RFP). At 48 h post-transfection, cells were analysed for red fluorescence. A reduction in red fluorescence compared with the control indicated reduction in expression of RV-G-RFP or RV-N-RFP protein. Magnification, 100X

Effect of dual gene targeting siRNAs expression plasmid on rabies virus multiplication

To analyse the effect of the dual-gene-targeting siRNA expression plasmid on RV multiplication, BHK-21 cells were transfected with psi-G7N and challenged with the RV PV-11 strain. There was a reduction in RV fluorescent foci in cells treated with either single (si-G7 or si-N)- or dual (si-G7N)-gene-targeting siRNAs compared with control siRNA, indicating inhibition of RV multiplication (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of single and dual gene silencing constructs expressing siRNAs targeting RV-G and N genes to inhibit RV multiplication in BHK-21 cells. Cells were transfected with dual (psi-G7N) or single (psi-G7 or psi-N) gene silencing construct expressing siRNAs or control (psi-C) siRNA and challenged with the RV-PV-11 strain at an MOI of 0.01. At 48 h post-challenge, the presence of RV in infected BHK-21 cells was detected by staining with FITC-labeled antibody against rabies virus nucleocapsid and counterstained with DAPI. Magnification, 200X

For quantitative estimation of the gene silencing effect, RV titers were determined in supernatants of BHK-21 cells that had been treated with single- and dual-gene-targeting siRNAs and challenged with RV. All the siRNAs expressing plasmids, in four independent experiments, were capable of causing a reduction in RV titer compared to the control (Fig. 4). The reduction in RV titer was 87.4 ± 10.6 %, 86.8 ± 8.8 % and 85.9 ± 16.5 % with psi-G7N, psi-G7 and psi-N, respectively. This clearly indicated that both si-G7 and si-N, in single and dual form, could inhibit RV multiplication in BHK-21 cells.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative evaluation of single and dual gene silencing constructs expressing siRNAs targeting the RV-G and N genes to inhibit RV release in BHK-21 cells. The cell culture supernatant was harvested from BHK-21 cells transfected with single and dual gene silencing constructs or a control siRNA construct and challenged with the RV PV-11 strain at an MOI of 0.01. The amount of RV in the supernatant was quantified using rabies fluorescent focus unit (ffu) assay. The percent reduction in RV titer was determined in comparison with control

Discussion

RV has an approximately 12-kb-long single-stranded RNA genome consisting of nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix (M), glycoprotein (G) and large polymerase (L) genes that encode proteins, namely N, P, M and G and L. Among the five RV proteins, the N, P and L proteins are important targets for RNAi due to their role in both viral transcription and replication. Previous in vitro studies have indicated that short RV-N cDNA, artificial microRNAs and synthetic siRNA targeting RV-N could interfere with RV replication [10, 11, 15]. Other targets for RV RNAi were non-structural genes such as P [11] and L [13] with limited antiviral potential. Our group has also evaluated siRNAs targeting RV-L and N genes delivered using an adenoviral vector for their anti-rabies-virus potential in vitro in BHK-21 cells and in vivo in mice and showed that they provided a moderate level of protection against lethal RV-CVS-11 challenge [12]. RV-G also remained a potential target for RNAi, as it is essential for trans-synaptic spread of RV between neurons in vivo [16, 17]. In the present study, siRNAs targeting RV-G were designed and evaluated, either alone or in combination with siRNA targeting RV-N, for inhibition of RV multiplication.

To select siRNAs that are effective against different strains of RV, the regions of the RV-G conserved among different strains were identified and used for designing siRNAs. While selecting siRNAs, a conserved region of the RV-G gene with no potential for secondary structure formation was considered using siRNA design algorithms. Since screening of siRNAs against RV is tedious and time-consuming and requires intense safety conditions, a simple method for screening siRNAs based on plasmid co-transfection was used. The siRNAs (siG-1 to 9) targeting RV-G and si-N targeting RV-N genes were synthesized in an shRNA form and cloned into an siRNA expression vector under the control of a U6 promoter. To facilitate screening of effective siRNAs, we constructed the target reporter plasmids pDsRed-G and pDsRed-N, in which full-length RV-G and N coding regions containing siRNAs target sequences were fused in-frame with the RFP gene to express the fusion proteins RV-G-RFP and RV-N-RFP. The siRNAs that executed cleavage of the viral mRNA led to reduced expression of the RFP reporter gene. This provided a simple and impartial model for assessing the efficacy of gene silencing by analysis of fusion protein expression by fluorescence microscopy. In three independent experiments, the siRNAs (si-G7 and si-N) consistently inhibited expression of the RFP fusion versions of the RV-G and N protein, indicating that they are potent siRNAs that should be studied further. This approach of screening effective siRNAs targeting different viral genes has been reported previously [12, 20, 25–28].

siRNA-mediated gene silencing functions by degrading mRNA that shares a complementary sequence; therefore, quantification of target gene transcripts in siRNA-treated cells indicated the efficiency of the siRNAs. In this study, quantification of RV-G-RFP fusion transcripts using real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to analyze the effect of different siRNAs on RV-G mRNA expression. The highest (64.5 %) level of reduction in silencing of RV-G mRNA in si-G7-treated cells was seen compared with control (si-C-treated) cells. To confirm the antiviral potential of RV-G-specific siRNAs, we monitored the presence of virus in infected cells and viral progeny in siRNA-treated and RV-infected cell culture supernatant. The reduction in the number of fluorescent foci was correlated with a decrease in the infectious RV titer in siRNAs-treated BHK-21 cells. The decrease in the release of infectious RV from si-G7-treated cells was greater (86.8 %) than in the other siRNA-treated cells. Similarly, treatment with si-N, targeting RV-N, also resulted in a reduction (85.9 %) in release of infectious RV compared to control. This indicated that both siRNAs, namely, si-G7 and si-N, could inhibit RV multiplication in BHK-21 cells. The reduced infectivity titer of RV due to RV-G silencing could be due to the production of RV without RV-G, which might have restricted its spread from one infected cell to another. A requirement for RV-G in cell-to-cell transfer of virus has been reported [16, 29–31]. Similarly, a reduction in RV titer with a silencing effect on RV-N could occur in two ways: as a major viral structural protein and as a regulatory protein to switch from viral gene expression to genome replication. The intracellular ratio of leader RNA to N protein regulates the switch from viral gene transcription to viral genome replication [32].

To analyse the cumulative effect of both of the siRNAs (si-G7 and si-N) on RV gene expression and multiplication, an siRNA expression plasmid encoding dual siRNAs under the independent control of an U6 promoter was constructed. The functionality of siRNAs to knock down the expression of RV-G and N genes was analysed using a plasmid co-transfection approach, which indicated that a dual-siRNA-expressing plasmid could reduce the expression of both the target genes. Furthermore, a dual gene silencing construct also inhibited the multiplication of RV in infected BHK-21 cells as analysed by in vitro challenge of siRNAs-treated cells with RV-PV-11. The reduction in RV titer in the infected cell culture supernatant was 87.4 %, which was significantly similar to the effect produced by individual siRNAs, indicating no cumulative effect. The approach of using multigene siRNAs or multi-siRNAs/miRNAs targeting a single gene has been reported for many viruses, with a variable degree of inhibition of virus replication [11, 33–35].

The results of this study indicated that siRNAs (si-G7 and si-N) targeting RV-G and N genes in single and dual form were effective in inhibiting RV multiplication in BHK-21 cells. This also suggested that siRNAs targeting RV-G and N can be used as antiviral agent against RV infection. However, before recommending them for therapeutic use, much work on targeted delivery, dose and time of therapeutic siRNAs administration is needed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was generously supported in part by the project “Evaluation of anti-rabies effect of small interfering RNA (siRNA) delivered through viral vector” Grant No. BT/PR9941/AGR/ 36/22/2007 from Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India and Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), India.

References

- 1.WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies . Technical Report 931. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiktor TJ, MacFarlan RI, Foggin CM, Koprowski H. Antigenic analysis of rabies and mokola virus from Zimbabwe using monoclonal antibodies. Dev Biol Stand. 1984;57:199–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickford AS, Cogoni C. RNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:871–882. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2245-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Chan CY, He ML. RNA interference and antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5169–5179. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal N, Dasaradhi PV, Mohmmed A, Malhotra P, Bhatnagar RK, Mukherjee SK. RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev: MMBR. 2003;67:657–685. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.657-685.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Xia J. Progress on RNAi-based molecular medicines. Intl J Nanomed. 2012;7:3971–3980. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S31897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu R, Zhang S, Fooks AR, Li Z, Li Q, Liu Y, Zhang F, Li J, Liu Q, Fu Z (2006) siRNA-directed inhibition of rabies virus and protection from rabies infection in mouse models. In: Annals of the 17th Rabies in the Americas meeting, Brasilia, Brazil, pp 40

- 10.Brandao PE, Castilho JG, Fahl W, Carnieli P, Oliveira Rde N, Macedo CI, Carrieri ML, Kotait I. Short-interfering RNAs as antivirals against rabies. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:224–225. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702007000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israsena N, Supavonwong P, Ratanasetyuth N, Khawplod P, Hemachudha T. Inhibition of rabies virus replication by multiple artificial microRNAs. Antiviral Res. 2009;84:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta PK, Sonwane AA, Singh NK, Meshram CD, Dahiya SS, Pawar SS, Gupta SP, Chaturvedi VK, Saini M. Intracerebral delivery of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) using adenoviral vector protects mice against lethal peripheral rabies challenge. Virus Res. 2012;163:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonwane AA, Dahiya SS, Saini M, Chaturvedi VK, Singh RP, Gupta PK. Inhibition of rabies virus multiplication by siRNA delivered through adenoviral vector in vitro in BHK-21 cells and in vivo in mice. Res Vet Sci. 2012;93:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YJ, Zhao PS, Zhang T, Wang HL, Liang HR, Zhao LL, Wu HX, Wang TC, Yang ST, Xia XZ. Small interfering RNAs targeting the rabies virus nucleoprotein gene. Virus Res. 2012;169:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wunner WH, Pallatroni C, Curtis PJ. Selection of genetic inhibitors of rabies virus. Arch Virol. 2004;149:1653–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etessami R, Conzelmann KK, Fadai-Ghothi B, Natelson B, Tsiang H, Ceccaldi PE. Spread and pathogenic characteristics of a G-deficient rabies virus recombinant: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2147–2153. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-9-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan X, Mohankumar PS, Dietzschold B, Schnell MJ, Fu ZF. The rabies virus glycoprotein determines the distribution of different rabies virus strains in the brain. J Neuro Virol. 2002;8:345–352. doi: 10.1080/13550280290100707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prehaud C, Lay S, Dietzschold B, Lafon M. Glycoprotein of nonpathogenic rabies viruses is a key determinant of human cell apoptosis. J Virol. 2003;77:10537–10547. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10537-10547.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietzschold B, Li J, Faber M, Schnell M. Concepts in the pathogenesis of rabies. Future Virol. 2008;3:481–490. doi: 10.2217/17460794.3.5.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuang ST, Ji WT, Chen YT, Lin CH, Hsieh YC, Liu HJ. Suppression of bovine ephemeral fever virus by RNA interference. J Virol Methods. 2007;145:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim MS, Kim KH. Inhibition of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus replication using a short hairpin RNA targeting the G gene. Arch Virol. 2011;156:457–464. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ui-Tei K, Naito Y, Takahashi F, Haraguchi T, Ohki-Hamazaki H, Juni A, Ueda R, Saigo K. Guidelines for the selection of highly effective siRNA sequences for mammalian and chick RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;9:936–948. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2003–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.OIE Terrestrial Manual 2011 (2011) Chapter 2.1.13. Rabies. http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/2.01.13_RABIES. Accessed May 2011

- 25.Sanchez AB, Perez M, Cornu T, Torre JC. RNA interference-mediated virus clearance from cells both acutely and chronically infected with the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol. 2005;79:11071–11081. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11071-11081.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng H, Cui FY, Chen XH, Pan YC. Inhibition of gene expression directed by small interfering RNAs in infectious bronchitis virus. Acta Virol. 2007;51:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong SP, Chu JJH, Ng ML. Inhibition of West Nile virus replication in cells stably transfected with vector-based shRNA expression system. Virus Res. 2008;135:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du J, Gao S, Luo J, Zhang G, Cong G, Shao J, Lin T, Cai X, Chang H. Effective inhibition of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) replication in vitro. Virol J. 2011;8:292. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mebatsion T, Konig M, Conzelmann KK. Budding of rabies virus particles in the absence of the spike glycoprotein. Cell. 1996;84:941–951. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajramovic JJ, Münter S, Syan S, Nehrbass U, Brahic M, Gonzalez-Dunia D. Borna disease virus glycoprotein is required for viral dissemination in neurons. J Virol. 2003;77:12222–12231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12222-12231.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pulmanausahakul R, Li J, Schnell MJ, Dietzschold B. The glycoprotein and the matrix protein of rabies virus affect pathogenicity by regulating viral replication and facilitating cell-to-cell spread. J Virol. 2008;82:2330–2338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02327-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wunner WH. The chemical composition and molecular structure of rabies viruses. In: Baer GM, editor. The natural history of rabies. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu KL, Zhang X, Zhang J, Yang Y, Mu YX, Liu M, Lu L, Li Y, Zhu Y, Wu J. Inhibition of Hepatitis B virus gene expression by single and dual small interfering RNA treatment. Virus Res. 2005;112:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry SD, van der Wegen P, Metselaar HJ, Tilanus HW, Scholte BJ, van der Laan LJ. Simultaneous targeting of HCV replication and viral binding with a single lentiviral vector containing multiple RNA interference expression cassettes. Mol Ther. 2006;14:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Dai Y, Liu S, Guo H, Wang T, Ouyang H, Tu C. In vitro inhibition of CSFV replication by multiple siRNA expression. Antiviral Res. 2011;91:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.