Abstract

Enterovirus 71 (EV71) is a single-strand RNA virus that causes hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) in infants and young children, leading to neurological complications with significant morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, the pathogenesis of EV71 infection is not well understood. In this study, we investigated the IL-17F rs1889570 and rs4715290 gene polymorphisms in a Chinese Han population. Severe cases and cases with EV71 encephalitis had a significantly higher frequency of the rs1889570 T/T genotype and T allele. The serum IL-17F levels in rs1889570 T/T and C/T genotypes were also significantly elevated when compared to C/C genotypes. However, there was no significant difference observed in rs4715290 genotype distribution and allele frequency. These findings suggest that IL-17F rs1889570 gene polymorphisms are significantly associated with the susceptibility to severe EV71 infection in Chinese Han children.

Introduction

Enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection is one of the most common causative factors of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) and may lead to diseases with severe morbidity and a high rate of neurological disorders, such as aseptic meningitis, acute flaccid paralysis, and fatal neurogenic pulmonary edema [1, 2]. EV71 is a non-enveloped, single-strand positive sense RNA virus, which is taxonomically classified within the Enterovirus A species of the Enterovirus genus of the family Picornaviridae [3, 4]. EV71 was first isolated from the stool of an infant with fatal encephalitis in California [5]. Since it was initial described in 1974, outbreaks of EV71 infection have occurred periodically throughout the world, including Malaysia, Singapore, Japan, Australia, the United States, Germany, Taiwan, and mainland China [6–11]. However, the mechanisms underpinning the pathogenesis of EV71 infection and its associated complications still remain largely unknown.

Based on clinical manifestations and animal experiments [12–15], one hypothesis is that the inflammatory response, characterized by a cytokine storm, is induced by EV71 infection and subsequently leads to pathological changes in the central nervous system (CNS), resulting in further disruption of CNS stability. Anti-virus infections are often dominated by a Th1 response. There are studies showing that pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are increased in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid of fatal EV71 cases. Besides, the co-emergence of Th17 and Th1 cells has recently been observed in several viral infections, such as coronavirus [16], human immunodeficiency virus [17], simian immunodeficiency virus [18], respiratory syncytial virus [19] and cytomegalovirus [20]. One study showed that the Th17 subset was involved in the immunopathogenesis of EV71 infection and that the concentration of IL-17 in the sera of EV71 infected children was increased compared to controls [21]. Th17 responses are characterized by the production of IL-17 as the signature cytokine. The IL-17 cytokine family includes six members: IL-17A-F. Among them, IL-17A and IL-17F are the central players in the adaptive immune response. IL-17F, sharing 50% homology with IL-17A, has been considered as an inflammatory cytokine since it can induce many pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The IL-17F gene is located on chromosome 6p12.2. One of our lab’s previous studies showed IL-17F rs763780 was associated with protection against EV71 encephalitis [22]. In this study, we aimed to identify whether IL-17F rs1889570 and rs4715290 gene polymorphisms were associated with the susceptibility to severe EV71 infection in the Chinese Han population.

Patients were recruited from the Pediatric Department of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University and Qingdao Women and Children’s hospital, China. Most of them were from the Qingdao area while a small number were from the surrounding areas of Qingdao. The present study included 336 EV71-infected patients and 330 healthy controls who presented up for check-up during the same period. EV71 infection was diagnosed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). RNA was extracted from throat swabs, stool specimens, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or other tissue fluids that were collected from each patient on the day of admission. The control children had not been in contact with EV71-infected individuals, as confirmed by evaluating RNA extracted from throat swabs and stool specimens. All of the EV71-infected patients and the controls received a general physical and if necessary, laboratory examination.

HFMD was diagnosed by senior physicians with special training, according to the HFMD clinical diagnosis and treatment guidelines (2010) published by the Chinese Ministry of Health [23]. Based on the guidelines, the mild cases were characterized as herpetic stomatitis and a rash on the hands and feet, with or without fever. The cases clinically diagnosed with HFMD and with one or more of the following symptoms were defined as severe cases [23–25]: (1) persistent high fever; (2) muscle weakness, limb jitter, spasm, disorders of consciousness, weak or absent tendon reflexes, positive meningeal stimulation; (3) pallor, tachycardia, impaired peripheral circulation, abnormal blood pressure; (4) dyspnea or irregular breathing rhythm, cyanosis, increased lung wet rale, signs of lung consolidation; (5) high (> 15 × 109/L) or low (< 2 × 109/L) peripheral blood leukocyte counts; (6) significantly elevated blood glucose (> 9 mmol/L); (7) abnormal chest X-ray. Peripheral blood samples were collected in sterile vials containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Bloods cells and plasma were separated and kept at – 80 °C until use.

As described previously [24], fluorescent quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to detect the numbers of copies of viral RNA present in samples. Total RNA was extracted from 150 uL of various swab samples using an RNAiso Plus Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, total RNA was reverse transcribed with random hexamers using a Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Scientific). The cDNA was subjected to quantitative PCR in a 50 uL reaction mixture (Thermo Scientific DyNAmo SYBR Green qRT-PCR Kit) with the primers EV71-S (5′-GTTCTTAACTCACATAGCA-3′, nucleotides 2643–2661) and EV71-A (5′-TTGACAAAAACTGAGGGTT-3′, nucleotides 2983–2965) for EV71 VP1. The conditions consisted of a denaturation step at 95 °C for 15 min and 40 cycles of thermal cycling at 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 60 s. A series of dilutions containing 1 × 107, 1 × 106, 1 × 105, and 1 × 104 copies/uL of a DNA fragment derived from EV71 were used to make a standard curve for calculating the copy number of viral RNA in various samples. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using the MxproMx3000P system.

Genetic DNA was extracted from white blood cells using a commercial kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As described previously [24], we used the improved multiplex ligation detection reaction (iMLDR) technique, developed by Genesky Biotechnologies Inc. (Shanghai, China), to detect the rs1889570 and rs4715290 polymorphisms in the IL-17 gene. The product size was 161 bp for rs1889570 and 233 bp for rs4715290. For rs1889570 gene polymorphism analysis, PCR was performed using the forward primer GAGGGGAGGACCCTTCCTGA and the reverse primer GCCCACCTTTTCTCCCCAAG. For rs4715290 gene polymorphism analysis, PCR was performed using the forward primer GGAGAAAAGTGGGCAGGAGAA and the reverse primer CATAACTCCCACAGCCCTCGTTA. The PCR program was 95 °C for 2 min; 11 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 65 °C–0.5 °C/cycle for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min 30 s; and 24 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 59 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min 30 s; followed by 72 °C for 2 min and holding at 4 °C. The PCR products were purified by digestion with 1 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase at 37 °C for 1 h and at 75 °C for 15 min. The ligation reaction contained 2 ul of 10× ligase buffer, 0.2 ul of Taq DNA ligase, 1 ul of probe mixture, and 3 ul of purified PCR product mixture. In a double connection reaction, each site contains two 5′ ends of allele specific probes and a 3′ end of an allele specific probe. Each allele specific connection product was distinguished by its fluorescence, while different loci were distinguished by the different lengths added to the 3′ end of the allele specific probe. The probes were as follows:

rs1889570RC: TTCCGCGTTCGGACTGATATCACACCTTTTGTCTTGGAGCAGG

rs1889570RT: TACGGTTATTCGGGCTCCTGTCACACCTTTTGTCTTGGAGCAGA

rs1889570RP: CCATAAAGAAATTCTTTGATTTACCTTGTCT TTTTTTTTTTTTTT

rs4715290FG: TTCCGCGTTCGGACTGATAT TGAAGCTGCTTCAGGAAACAATGG

rs4715290FA: TACGGTTATTCGGGCTCCTGT TGAAGCTGCTTCAGGAAACAACGA

rs4715290FP: CAAAAAAGCTAAATACCCTAACAAAAGATATGC TTTTTTTTTTTTTT

The ligation cycling program consisted of 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min and 56 °C for 4 min; and then holding at 4 °C. The ligation products were analyzed using a 3130×l Genetic Analyzer (ABI), and the raw data was analyzed using GeneMapper 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Plasma concentrations of IL-17F were assessed using commercial ELISA kits (Ray Biotech Inc., USA) for human IL-17F according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Each sample was assayed in duplicate and the values were within the linear portion of the standard curve.

Data were tested by the chi-square test for their degree of fit with the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) between the observed and expected values. The frequencies of genotypes and alleles were compared between the groups of patients with EV71-related mild cases and severe cases by using the chi-square test. The association of the IL17F gene polymorphisms with the risk of severe disease was evaluated by calculating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), using logistic regression. The effects of the IL-17 rs1889570 genotype on EV71 infection was evaluated by using the Kruskal–Wallis statistic for the non-normally distributed parameters, and the data were expressed as median values (25th–75th percentile values). The IL-17F levels were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. The significance was set at a p-value of 0.05.

We examined a group of 336 EV71-infected children, including 181 males and 155 females, aged from 0.5 to 7.9 years. There were 221 mild cases and 115 severe cases (including 72 cases of EV71 encephalitis). One severe case died. The genotype frequencies of each group obeyed the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p > 0.05). Genotype distribution and allele frequency of IL17F rs1889570 and rs4715290 in EV71-infected children and healthy controls are presented in Table 1. Considering the rs1889570 gene polymorphism, the genotype distribution in the control group was 40% (132/330) for C/C, 50.30% (166/330) for C/T and 9.7% (32/330) for T/T, which was similar to that of EV71-infected patients: 33% (112/336) for C/C, 53.27% (179/336) for C/T and 13.93% (45/336) for T/T (p = 0.118). The frequencies of the C and T alleles were 65.15% (430/660) and 34.85% (230/660) in the control group, compared to 59.97% (403/672) and 40.03% (269/672), respectively, in the EV71 infected patients (p = 0.54). In addition, the severe cases had a significantly higher frequency of the T/T genotype than the mild cases (p = 0.01). In mild cases, the genotype distribution was 37.56% for C/C, 52.49% for C/T and 9.95% for T/T, while it was 25.22% for C/C, 54.78% for C/T and 20.00% for T/T in severe cases. Similarly, the T allele was observed with significantly higher frequency in severe cases than in mild cases (47.39% vs. 36.20%, OR = 1.588, 95% CI = 1.1–2.2, p = 0.006). Furthermore, the genotype T/T and allele T in cases with EV71 encephalitis were also more frequent than those observed in the mild cases (22.22% vs. 9.95%, P = 0.001 and 52.08% vs. 36.20%, OR = 1.916, 95% CI = 1.3–2.8, P = 0.001). However, for the rs4715290 polymorphism, no differences were observed in genotype distribution and allele frequency between controls and EV71-infected patients (p = 0.773, p = 0.685). There were no statistical differences in rs4715290 genotype distribution and allele frequency when comparing severe cases (p = 0.621, p = 0.541) or cases with EV71 encephalitis (p = 0.786, p = 0.567) with mild cases.

Table 1.

Genotypic and allelic frequencies of the rs1889570 and rs4715290 polymorphisms in controls and EV71-infected patients

| SNP | Control (n = 330) | EV71-infected patients (n = 336) | Mild cases (n = 221) | Severe cases (n = 115) | EV71 encephalitis (n = 72) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1889570 | |||||||

| Genotype | |||||||

| C/C | 132 (40.00%) | 112 (33.33%) | 83 (37.56%) | 29 (25.22%) | 13 (18.06%) | 0.118a | |

| C/T | 166 (50.30%) | 179 (53.27%) | 116 (52.49%) | 63 (54.78%) | 43 (59.72%) | 0.010b | |

| T/T | 32 (9.7%) | 45 (13.93%) | 22 (9.95%) | 23 (20.00%) | 16 (22.22%) | 0.001c | |

| Allele | 0.054a | 1.248 (0.997–1.556)a | |||||

| C | 430 (65.15%) | 403 (59.97%) | 282 (63.80%) | 121 (52.61%) | 69 (47.92%) | 0.006b | 1.588 (1.144–2.203)b |

| T | 230 (34.85%) | 269 (40.03%) | 160 (36.20%) | 109 (47.39%) | 75 (52.08%) | 0.001c | 1.916 (1.316–2.801)c |

| rs4715290 | |||||||

| Genotype | |||||||

| A/A | 246 (74.55%) | 257 (76.49%) | 167 (75.57%) | 90 (78.26%) | 57 (18.06%) | 0.773a | |

| A/G | 79 (23.94%) | 73 (21.73%) | 49 (22.17%) | 24 (20.87%) | 14 (59.72%) | 0.621b | |

| G/G | 5 (1.52%) | 6 (1.79%) | 5 (2.26%) | 1 (0.87%) | 1 (22.22%) | 0.786c | |

| Allele | 0.685a | 1.076 (0.783–1.483)a | |||||

| A | 571 (86.52%) | 587 (87.35%) | 383 (86.65%) | 204 (88.70%) | 128 (88.89%) | 0.541b | 1.209 (0.732–1.955)b |

| G | 89 (13.48%) | 85 (12.65%) | 59 (13.35%) | 26 (11.30%) | 16 (11.11%) | 0.567c | 1.232 (0.679–2.188)c |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

aControls vs. EV71-infected patients

bSevere cases vs. mild case

cEV71 encephalitis vs. mild cases. EV71 encephalitis was included in the severe cases

Next, we observed the effects of the rs1889570 gene polymorphism on the severity of EV71 infection. As shown in Table 2, there were obvious differences between the different genotypes in EV71 infected patients in relation to the duration of fever (p = 0.0008), white blood cell (WBC) counts (p = 0.045), C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (p = 0.038) and blood glucose (BG) concentrations (p = 0.019). More details were provided as follows: the median duration of fever were 1.5 (1–2.5) days for C/C, 2 (1–3) days for C/T and 2.5 (1.5–4) days for T/T; the median WBC counts were 7.7 (6.6–9.8) × 109/L for C/C, 8 × 109/L for C/T and 9.2 × 109/L for T/T; the median CRP levels were 5.1 mg/L for C/C, 5.8 mg/L for C/T and 7.1 mg/L for T/T and the median BG concentration were 5.4 (4.7–6.9) mmol/L for C/C, 5.7 (5.1–6.8) mmol/L for C/T and 6.1 (5.4–9.0) mmol/L for T/T. However, there was no significant differences in the different genotypes of EV71 infected patients with regard to gender, age, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), cardiac creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) levels and EV71 viral loads.

Table 2.

Effects of rs1889570 gene polymorphism on the severity of EV71 infection

| C/C (n = 112) | C/T (n = 179) | T/T (n = 45) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n) | 70 | 89 | 22 | |

| Female (n) | 42 | 90 | 23 | 0.08a |

| Ages (years) | 3.9 (2.9–5.45) | 3.7 (2.3–5.2) | 3.7 (2.25–5.65) | 0.382b |

| Duration of fever (days) | 1.5 (1–2.5) | 2 (1–3) | 2.5 (1.5–4) | 0.0008b |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 7.7 (6.6–9.8) | 8 (5.8–10) | 9.2 (7.15–13.3) | 0.045b |

| CRP (mg/L) | 5.1 (2.6–8.3) | 5.8 (3–9) | 7.1 (4.85–10.2) | 0.038b |

| BG (mmol/L) | 5.4 (4.7–6.9) | 5.7 (5.1–6.8) | 6.1 (5.4–9.0) | 0.019b |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.5 (15.25–25) | 19 (15–25) | 18 (16.5–25) | 0.76b |

| AST (U/L) | 25 (20–33) | 25 (19-34) | 25 (18–35) | 0.964b |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 12 (9.25–19) | 14 (9–19) | 12 (8–19) | 0.706b |

| EV71 load (log10 copies/ul) | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) | 4.3 (3.8–6.8) | 4.3 (3.9–6.8) | 0.091b |

WBC, white blood cell count; CRP, C-reactive protein; BG, blood glucose; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CK-MB, cardiac creatine kinase-MB fraction

aGroups compared using chi-square test

bValues expressed as median (25th–75th percentile values); groups compared using nonparametric test

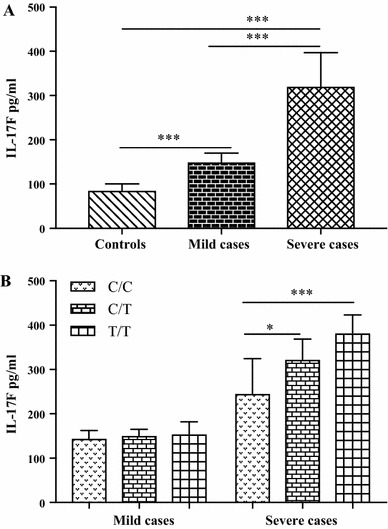

Serum IL-17F levels were significantly different among severe cases, mild cases and healthy controls (320.7 ± 76, 150 ± 20.01, 85.76 ± 14.74 pg/ml) (Fig. 1A). IL-17F levels were measured for each genotype in EV71 infected children. In severe cases with EV71 infection, our data showed that the IL-17F levels in patients with the rs1889570 T/T (382.3 ± 40.83 pg/ml) genotypes and C/T (322.8 ± 45.71 pg/ml) genotypes were significantly higher than those with C/C genotypes (246.1 ± 78.54 pg/ml) (Fig. 1B). However, there were no significant differences in the concentrations of IL-17F among rs1889570 genotypes in mild cases with EV71 infection (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Serum levels of IL-17F were measured in 42 EV71-infected cases (21 mild cases and 21 severe cases, C/C = 12, C/T = 16, T/T = 14), and 23 controls (C/C = 7, C/T = 8, T/T = 8). Values were expressed as mean±SD. (A) IL-17F levels were significantly different in severe cases, mild cases and controls (***p < 0.001, severe cases vs. controls, mild cases vs. controls, severe case vs. mild cases). (B) IL-17F levels in T/T and C/T genotypes were significantly higher than with C/C genotypes in severe cases (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05), but there were no differences between different genotypes in mild cases

EV71 infection results in several severe complications with high mortality and disability in children. Numerous factors influence the immune response to EV71 infection. In recent years, many association studies between host genetic factors and EV71 infection have been performed. Our lab has previously demonstrated that polymorphisms in genes of IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-4, CXCL-10, CCL-2, TLR3, OAS3 and CPTII were associated with the susceptibility and/or the severity of EV71 infection [24–32]. These cytokines/chemokines and receptors are all necessary for an efficient inflammatory response.

IL-17F rs1889570 and rs4715290 located in the promotor region. Previous studies have reported the IL-17F rs1889570 gene polymorphism as being involved in several diseases, such as asthma [33, 34] and tuberculosis [35]. To date, no study has been performed on the rs4715290 gene polymorphism. Here, we aimed to identify whether the IL-17F rs1889570 and rs4715290 gene polymorphisms were associated with susceptibility to severe EV71 infection in the Chinese Han population. No significant difference was found between EV71 infection in children and the healthy controls in terms of the distribution of IL-17F rs1889570 and rs4715290 genotypes and alleles. The data also revealed that the rs4715290 gene polymorphism was not associated with the severity of EV71 infection when comparing severe cases and EV71 encephalitis with mild cases. However, we found the frequency of the rs1889570 T/T genotype and T allele were markedly overrepresented in severe cases, including cases of EV71 encephalitis, when compared to mild cases and healthy controls, which suggested that the polymorphism in rs1889570 might be associated with the severity of EV71 infection in the Chinese Han population. This result is consistent with the reported results for asthma in a South Indian population [34] and tuberculosis in a Chinese population [35].

As the epidemiological studies showed, young age, male gender, high WBC counts, prolonged high fever, high BG concentration and high CRP levels were the key factors associated with severe EV71 infection in patients [36]. In addition, some of these factors, such as CRP and WBC, are also common indicators of the inflammatory response. In our study, we found significantly higher WBC counts, CRP levels, BG concentrations and a longer duration of fever in EV71 infected subjects with the rs1889570 T/T genotype. However, there were no differences between other organ function parameters, such as ALT, AST, CK-MB, among the different genotypes after EV71 infection. Taken together, these data all indicate that the IL-17F rs1889570 gene polymorphism is involved in the inflammatory process following EV71 infection.

The actual mechanism of how IL-17F gene polymorphisms affect the severity of EV71 infection is unclear, but the following postulation may be plausible. IL-17 may play an immunopathological role in tissue damage during viral infection. Accumulating data suggest that IL-17 can augment the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8 and IL-1β, as well as chemokines, including MCP-1, CXCL-6, CXCL-7 and CXCL-8, and matrix metalloproteinases. This will result in the recruitment, mobilization and activation of immune cells leading to several inflammatory processes and tissue damage [17, 37, 38]. In addition, in the central nervous system (CNS), human Th17 cells could promote blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption and CNS inflammation by co-expressing IL-17, IL-22 and granzyme B promoting the recruitment of additional CD4+ lymphocytes [39]. Huppet et al also reported that IL-17 induced BBB disruption through the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by NAD(P)H oxidase and xanthine oxidase, which are subsequently responsible for the disruption and down-regulation of tight junction molecules and the activation of the endothelial contractile machinery [40]. Furthermore, in the EV71-infected rhesus monkey infant model, the up-regulation of IL-17 was sustained in the peripheral blood [15]. ROR γt has been proven to be the key transcription factor for the differentiation of Th17 cells and the release of IL-17 [41]. Chen et al revealed that the frequency of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood, the concentration of IL-17, and the level of expression of acid-related orphan nuclear receptor gamma t (ROR γt) significantly increased in EV71 infected children [21]. Based on the previous publications and our data, we further explored whether there was a relationship between IL-17F rs1889570 polymorphism and serum IL-17F levels in EV71-infected patients. The results showed significantly higher serum IL-17F levels in patients with the rs1889570 T/T genotype who had severe cases of EV71 infection. Since IL-17F rs1889570 is located on the promotor region, our findings suggest that the IL-17F rs1889570 gene polymorphism could affect IL-17F expression. Under such conditions, it could be concluded that rs1889570 T allele was likely to increase the severity of EV71 infection and the incidence of EV71 encephalitis by upregulating serum IL-17F levels, which could further induce a higher amount of upstream inflammatory mediators and BBB disruption. Perhaps this is one of the pathogenic mechanisms occurring following EV71 infection. Further multi-center studies with a larger sample size and multiple ethnic groups are required to determine the effects of genetic variants of the IL-17F gene.

Our study strongly demonstrates that IL-17F rs1889570 gene polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to severe EV71 infection and EV71 encephalitis in a Chinese Han population. Further studies are needed to identify the exact mechanism underlying the involvement of the IL-17F gene in the pathogenesis of EV71 infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their patients and families. The authors also appreciate the technical support from Genesky Biotechnologies Inc., Shanghai, China.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31171212).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, China.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from each child’s guardian.

Contributor Information

Fei Li, Email: lifei0615a@126.com.

Peipei Liu, Email: lqq-800@163.com.

Ya Guo, Email: 920605328@qq.com.

Zhenliang Han, Email: hanzhenliang@126.com.

Yedan Liu, Email: 297966191@qq.com.

Yuanyuan Wang, Email: wyymed@163.com.

Long Song, Email: sl578025506@163.com.

Jianguo Cheng, Email: chengj@ccf.org.

Zongbo Chen, Phone: +86 139 6961 5225, Email: drchen011@126.com.

References

- 1.McMinn PC. An overview of the evolution of enterovirus 71 and its clinical and public health significance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26(1):91–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ooi MH, Wong SC, Lewthwaite P, Cardosa MJ, Solomon T. Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of enterovirus 71. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70209-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown BA, Pallansch MA. Complete nucleotide sequence of enterovirus 71 is distinct from poliovirus. Virus Res. 1995;39(2–3):195–205. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathinayake PS, Hsu AC, Wark PA. Innate immunity and immune evasion by enterovirus 71. Viruses. 2015;7(12):6613–6630. doi: 10.3390/v7122961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt NJ, Lennette EH, Ho HH. An apparently new enterovirus isolated from patients with disease of the central nervous system. J Infect Dis. 1974;129(3):304–309. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AbuBakar S, Chee HY, Al-Kobaisi MF, Xiaoshan J, Chua KB, Lam SK. Identification of enterovirus 71 isolates from an outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) with fatal cases of encephalomyelitis in Malaysia. Virus Res. 1999;61(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(99)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho M. Enterovirus 71: the virus, its infections and outbreaks. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2000;33(4):205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kehle J, Roth B, Metzger C, Pfitzner A, Enders G. Molecular characterization of an enterovirus 71 causing neurological disease in Germany. J Neurovirol. 2003;9(1):126–128. doi: 10.1080/13550280390173364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMinn P, Stratov I, Nagarajan L, Davis S. Neurological manifestations of enterovirus 71 infection in children during an outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Western Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(2):236–242. doi: 10.1086/318454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu H, Utama A, Yoshii K, Yoshida H, Yoneyama T, Sinniah M, Yusof MA, Okuno Y, Okabe N, Shih SR, Chen HY, Wang GR, Kao CL, Chang KS, Miyamura T, Hagiwara A. Enterovirus 71 from fatal and nonfatal cases of hand, foot and mouth disease epidemics in Malaysia, Japan and Taiwan in 1997–1998. Jpn J Infect Dis. 1999;52(1):12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Chow VT, Chan KP, Ling AE, Poh CL. RT-PCR, nucleotide, amino acid and phylogenetic analyses of enterovirus type 71 strains from Asia. J Virol Methods. 2000;88(2):193–204. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(00)00185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin TY, Chang LY, Huang YC, Hsu KH, Chiu CH, Yang KD. Different proinflammatory reactions in fatal and non-fatal enterovirus 71 infections: implications for early recognition and therapy. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91(6):632–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb03292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin TY, Hsia SH, Huang YC, Wu CT, Chang LY. Proinflammatory cytokine reactions in enterovirus 71 infections of the central nervous system. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):269–274. doi: 10.1086/345905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SM, Lei HY, Liu CC. Cytokine immunopathogenesis of enterovirus 71 brain stem encephalitis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:876241. doi: 10.1155/2012/876241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Yang E, Pu J, Liu L, Che Y, Wang J, Liao Y, Wang L, Ding D, Zhao T, Ma N, Song M, Wang X, Shen D, Tang D, Huang H, Zhang Z, Chen D, Feng M, Li Q. The gene expression profile of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from EV71-infected rhesus infants and the significance in viral pathogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savarin C, Stohlman SA, Hinton DR, Ransohoff RM, Cua DJ, Bergmann CC. IFN-gamma protects from lethal IL-17 mediated viral encephalomyelitis independent of neutrophils. J Neuroinflamm. 2012;9:104. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue FY, Merchant A, Kovacs CM, Loutfy M, Persad D, Ostrowski MA. Virus-specific interleukin-17-producing CD4+ T cells are detectable in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2008;82(13):6767–6771. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02550-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cecchinato V, Franchini G. Th17 cells in pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection of macaques. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(2):141–145. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833653ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bystrom J, Al-Adhoubi N, Al-Bogami M, Jawad AS, Mageed RA. Th17 lymphocytes in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Viruses. 2013;5(3):777–791. doi: 10.3390/v5030777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arens R, Wang P, Sidney J, Loewendorf A, Sette A, Schoenberger SP, Peters B, Benedict CA. Cutting edge: murine cytomegalovirus induces a polyfunctional CD4 T cell response. J Immunol. 2008;180(10):6472–6476. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Tong J, Liu H, Liu Y, Su Z, Wang S, Shi Y, Zheng D, Sandoghchian S, Geng J, Xu H. Increased frequency of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood of children infected with enterovirus 71. J Med Virol. 2012;84(5):763–767. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv T, Li J, Han Z, Chen Z. Association of interleukin-17F gene polymorphism with enterovirus 71 encephalitis in patients with hand, foot, and mouth disease. Inflammation. 2013;36(4):977–981. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9629-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.China MoHotPsRo A guidebook of HFMD diagnosis and treatment (2010 edition) Int J Resp. 2010;30(24):1473–1475. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F, Liu XP, Li JA, Han ZL, Liu PP, Wang YY, Song L, Chen ZB. Correlation of an interleukin-4 gene polymorphism with susceptibility to severe enterovirus 71 infection in Chinese children. Arch Virol. 2015;160(4):1035–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li JA, Chen ZB, Lv TG, Han ZL. Genetic polymorphism of CCL2-2518, CXCL10-201, IL8+781 and susceptibility to severity of enterovirus-71 infection in a Chinese population. Inflamm Res. 2014;63(7):549–556. doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0724-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JA, Chen ZB, Lv TG, Han ZL, Liu PP. Impact of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphism on severity of enterovirus 71-infection in Chinese children. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(18):1842–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu P, Liu X, Hu J, Han Z, Li F, Wang Y, Song L, Chen Z. Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 2 polymorphism may be associated with enterovirus 71 severe infection in a Chinese population. Arch Virol. 2016;161(5):1217–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2785-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He H, Liu S, Liu PP, Li QB, Tan YX, Guo Y, Li F, Wang YY, Liu YD, Yang CQ, Chen ZB. Association of toll-like receptor 3 gene polymorphism with the severity of enterovirus 71 infection in Chinese children. Arch Virol. 2017;162(6):1717–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan Y, Yang T, Liu P, Chen L, Tian Q, Guo Y, He H, Liu Y, Chen Z. Association of the OAS3 rs1859330 G/A genetic polymorphism with severity of enterovirus-71 infection in Chinese Han children. Arch Virol. 2017;162(8):2305–2313. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Chen ZZ, Lv TG, Liu PP, Chen ZB. Association of IP-10 gene polymorphism with susceptibility to enterovirus 71 infection. Biomed Rep. 2013;1(3):410–412. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan A, Li J, Liu P, Chen Z, Hou M, Wang J, Han Z. Association of interleukin-6-572C/G gene polymorphism and serum or cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 level with enterovirus 71 encephalitis in Chinese Han patients with hand, foot, and mouth disease. Inflammation. 2015;38(2):728–735. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9983-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Zhao N, Su NL, Sun JL, Lv TG, Chen ZB. Association of interleukin 10 and interferon gamma gene polymorphisms with enterovirus 71 encephalitis in patients with hand, foot and mouth disease. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44(6):465–469. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.649490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin Y, Deng Z, Cao C, Li L. IL-17 polymorphisms and asthma risk: a meta-analysis of 11 single nucleotide polymorphisms. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):981–988. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1044251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raeiszadeh Jahromi S, Mahesh PA, Jayaraj BS, Holla AD, Vishweswaraiah S, Ramachandra NB. IL-10 and IL-17F promoter single nucleotide polymorphism and asthma: a case-control study in South India. Lung. 2015;193(5):739–747. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng R, Yue J, Han M, Zhao Y, Liu L, Liang L. The IL-17F sequence variant is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. Gene. 2013;515(1):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Q, MacDonald NE, Smith JC, Cai K, Yu H, Li H, Lei C. Severe enterovirus type 71 nervous system infections in children in the Shanghai region of China: clinical manifestations and implications for prevention and care. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(5):482–487. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang SH, Dong C. IL-17F: regulation, signaling and function in inflammation. Cytokine. 2009;46(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin W, Dong C. IL-17 cytokines in immunity and inflammation. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2(9):e60. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, Dodelet-Devillers A, Cayrol R, Bernard M, Giuliani F, Arbour N, Becher B, Prat A. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13(10):1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nm1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huppert J, Closhen D, Croxford A, White R, Kulig P, Pietrowski E, Bechmann I, Becher B, Luhmann HJ, Waisman A, Kuhlmann CR. Cellular mechanisms of IL-17-induced blood–brain barrier disruption. FASEB J. 2010;24(4):1023–1034. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17 + T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126(6):1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]