Abstract

In this study, human enterovirus C117 (EV-C117) was detected in a 3-month-old boy diagnosed with pneumonia in China. A phylogenetic analysis showed that this strain was genetically closer to the Lithuanian strain than to the USA strain.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00705-019-04196-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

The genus Enterovirus of the family Picornaviridae consists of 15 species, including Enterovirus A–L and Rhinovirus A–C (http://www.picornaviridae.com). Enteroviruses (EVs) A–D and human rhinoviruses (HRVs) A–C infect humans and mostly affect children under one year of age. EV infections cause a variety of diseases with various clinical manifestations, ranging from mild febrile illness to severe systemic infections [5, 7].

Human enterovirus 117 (EV-C117), which belongs to the species Enterovirus C [1], was first identified in Lithuania in 2012 in a nasopharyngeal sample collected from a 45-month-old child [2, 3]. Since then, EV-C117 has been identified in four children from two other countries, China and Mongolia [8]. Here, we report the identification and complete genomic sequence of EV-117 in a child with pneumonia in China, which may provide more information for understanding EV-C117 infection.

A 3-month-old boy (patient CQ6747) from Guizhou Province was admitted to the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in June 2014 and diagnosed as having pneumonia. He had a 1-month history of phlegm in the throat, especially in the morning and at night, and tachypnoea. He occasionally regurgitated milk along with mucous sputum, and some medium and coarse moist rales could be heard in both lungs. Transient rhinorrhoea, paroxysmal cough, and diarrhoea without fever were apparent during the course of the disease. Laboratory examinations performed at admission revealed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count (7.93 × 109/L) and C-reactive protein level (< 8 mg/L), with a mildly elevated platelet count (429 × 109/L), and a high percentage lymphocytes (67%). Two days before admission, an X-ray radiograph showed slight interstitial changes in both lungs, and routine blood examination revealed elevated WBC (12.01 × 109/L) and platelet (617 × 109/L) counts. Cephalosporin antibiotics for treating the infection for more than 20 days had no obvious effect. A nasopharyngeal aspirate was collected from the child at admission, and the parents gave written informed consent for their child to participate in the study. We extracted RNA and DNA from the nasopharyngeal aspirate sample using aseptic techniques and tested the viral nucleic acids for evidence of respiratory viruses. Using molecular methods described previously, we tested for influenza virus (A, B and C), EV, metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, human bocavirus, parainfluenza virus (types 1-4), and coronaviruses (229E and OC43) [4, 6]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Children’s Hospital of the Chongqing Medical University.

The sample was positive for EV and parainfluenza virus type 3. IgG antibodies against cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus were also detected, while the sputum culture was negative for these viruses. To determine the enterovirus type, we amplified a portion of the 5’NCR-VP4/VP2 region of the enterovirus by nested PCR as described previously [4, 6]. The 330-bp amplicon was sequenced, and Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) revealed a high degree of similarity to EV-C117.

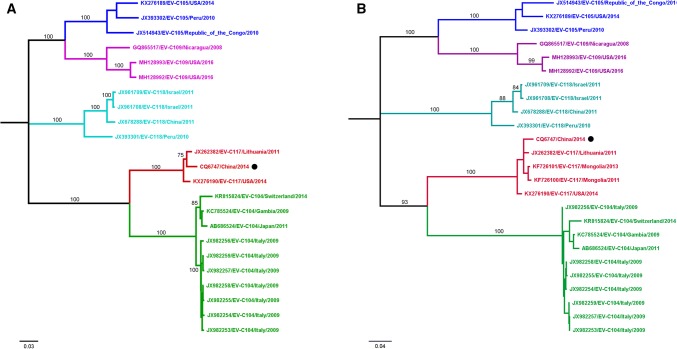

Using multiple primers (Table 1), we determined the full-length viral genome sequence of the strain detected in patient CQ6747 (GenBank accession no. MK089787), which was found to consist of 7364 nucleotides, excluding the poly(A) tail. The 5’UTR contains 672 nucleotides, and the 3’UTR consists of 70 nucleotides. The CQ6747 genome contains a single open reading frame from nt 673 to 7294 encoding a 2454-amino-acid polyprotein. The base composition of the full genome is 27.6% A, 23.7% C, 24.6% G, and 24.2% U. The complete genome sequence was compared with those of 22 HEV-C strains available in the GenBank database, which included EV-104, EV-105, EV-109, EV-117, and EV-118. The CQ6747 isolate shares 73.8%-81.6% nucleotide sequence identity in the coding region with other HEV-C strains, including EV-104 (81.2%-81.6%), EV-105 (73.8%-74.0%), EV-109 (73.8%-73.9%), and EV-118 (74.0%-74.4%), and shares 96.7%-97.5% nucleotide sequence identity with other EV-C117 strains (Table 2). After alignment using MEGA version 7.0, we constructed a phylogenetic tree by the maximum-likelihood method, using the Tamura-Nei model and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The resulting tree showed that CQ6747 belongs to genotype EV-C117 (Fig. 1A). Although it was genetically closer to the Lithuanian strain than to the USA strain, the CQ6747 strain was separate from both strains, with at least 75% bootstrap support.

Table 1.

The primers for amplifying the full-length genome sequences of EV-C117 used in this study

| Primer | Annealing temperature | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| EV117-L8 | 55 | CAGCTTGAGGGTTGTTCC |

| EV117-R1473 | GTTGATAATYTGGTGGGGR | |

| EV117-L1372 | 55 | AGYGAGGAWGGAAAGAAA |

| EV117-R2654 | AAGACTAATAATGGCGACAC | |

| EV117-L2510 | 55 | CAAAAGAAGTTCCAGCCC |

| EV117-R3728 | TCCATTGCTTCTTCCTCGT | |

| EV117-L3560 | 55 | ACGACTACTACCCAGCAA |

| EV117-R4725 | GGTGATAGTATGTGAGTTGG | |

| EV117-L4500 | 55 | CACATACTCACTACCACCC |

| EV117-R5814 | CATAACCACACCACCGCA | |

| EV117-L5675 | 55 | CCAGTAAATACCCCAACA |

| EV117-R6765 | CATACCTCCTTTCACACA | |

| EV117-L6564 | 55 | TAAGATCCCTGTACTGCT |

| EV117-R7333 | CACACTATATCCCAAACC |

Table 2.

Percent nucleotide sequence identity between CQ6747 and other EV-C genotypes

| Region | EV-C104 | EV-C105 | EV-C109 | EV-C118 | EV-C117 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete genome | 81.2-81.6 | 73.8-74.0 | 73.8-73.9 | 74.0-74.4 | 96.7-97.5 |

| 5’UTR | 71.6-72.8 | 71.3-72.6 | 74.6-75.2 | 71.6-73.1 | 98.2-98.7 |

| VP4 | 82.1-85.5 | 79.7-81.1 | 76.8-78.7 | 76.8-79.2 | 98.0-99.5 |

| VP2 | 73.1-74.1 | 74.4-74.6 | 72.9-73.3 | 74.4-74.9 | 96.4-97.4 |

| VP3 | 72.7-74.4 | 69.7-71.7 | 69.1-70.5 | 71.9-72.6 | 98.3-98.4 |

| VP1 | 69.8-70.3 | 69.0-70.6 | 68.4-69.5 | 68.4-68.5 | 96.5-97.4 |

| 2A | 83.4-84.1 | 76.5-76.7 | 78.0-78.9 | 80.7 | 97.5-98.8 |

| 2B | 84.5-85.5 | 79.3-80.0 | 76.9-80.4 | 71.1-74.5 | 95.8-96.9 |

| 2C | 86.8-88.1 | 73.1-75.0 | 74.8-75.0 | 75.1-75.5 | 96.2-96.8 |

| 3A | 89.7-91.6 | 69.6-73.1 | 71.9-73.8 | 73.4-74.2 | 96.5-97.3 |

| 3B | 83.3-89.3 | 69.6-71.2 | 72.7-75.7 | 72.7-81.8 | 92.4-93.9 |

| 3C | 89.2-90.1 | 71.0-72.6 | 71.9-73.0 | 72.3-74.1 | 96.3-96.7 |

| 3D | 89.2-90.1 | 75.7-76.6 | 75.2-75.6 | 74.9-77.0 | 96.3-96.8 |

| 3’UTR | 94.2-97.1 | 85.7-88.5 | 85.7-88.5 | 85.7-87.1 | 95.7-98.5 |

UTR, untranslated region

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic trees constructed based on the complete genome sequence and the VP1 gene sequence by the maximum-likelihood method in MEGA 7.0. The isolate from the present study is indicated by a black filled circle. A. Tree based on the complete genome. B. Tree based on the VP1 gene

The genome of the CQ6747 isolate has a typical enterovirus organization, encoding four structural proteins (VP4, VP2, VP3 and VP1) and seven non-structural proteins (2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C and 3D). The VP1 sequence of the CQ6747 isolate is 96.5%-97.4% identical to those of other EV-C117 isolates, and other genome regions displayed >90% sequence identity to EV-C117. Conversely, all genome regions of CQ6747 showed less similarity to other EV-C strains (including EV-C104, EV-C105, EV-C109, and EV-C118) (Table 2). A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the VP1 gene nucleotide sequences using the maximum-likelihood method. This illustrated the differences among the CQ6747 strain isolated in this study, the Lithuanian strain, the Mongolian strains, and the USA strain (Fig. 1B). In other phylogenetic trees that were constructed based on the 5’UTR, 3’UTR, VP2-VP4 region, 2A-2C region and 3A-3D region, more-pronounced genotype clustering was obtained, and the CQ6747 strain clustered with EV-C117 in all cases except for the 3’UTR tree (Supplemental Fig. 1).

In summary, we report the detection of EV-C117 in a child hospitalized with pneumonia. We demonstrated that the VP1-VP4, 2A-2C and 3A-3D gene regions of the CQ6747 strain were different from those of the other EV-C117 strains. Because parainfluenza virus type 3 and cytomegalovirus were also found in samples from this patient, the causal correlation between EV-C117 and respiratory disease could not be established. Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate the role of EV-C117 in respiratory illnesses in children.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental Figure 1 Phylogenetic trees constructed based on 5’UTR, VP4, VP2, VP3, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D and 3’UTR sequences by the maximum-likelihood method in MEGA 7.0. The isolate from the present study is indicated by a black filled circle. (TIFF 1350 kb)

Funding

This study was supported by China Mega-Project for Infectious Diseases Grant (2017ZX10103004, 2018ZX10713002 and 2018ZX10101003), the Natural Science Foundation of China (81703274), and Peking University Medicine Seed Fund for Interdisciplinary Research (BMU2018MX009).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Informed consent

We obtained informed consent from the child’s parents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Juan Du, Email: juandu@bjmu.edu.cn.

Teng Zhu, Email: zhuteng1991@163.com.

Lu Zhuang, Email: zhlu1986@163.com.

Pan-He Zhang, Email: panhez@yahoo.com.

Xiao-Ai Zhang, Email: babylovehopi@163.com.

Qing-Bin Lu, Phone: (+86)10-82805327, Email: qingbinlu@bjmu.edu.cn.

Wei Liu, Phone: (+86)10-63896082, Email: liuwei@bmi.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Brown B, Oberste MS, Maher K, Pallansch MA. Complete genomic sequencing shows that polioviruses and members of human enterovirus species C are closely related in the noncapsid coding region. J Virol. 2003;77:8973–8984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8973-8984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daleno C, Piralla A, Scala A, Baldanti F, Usonis V, Principi N, Esposito S. Complete genome sequence of a novel human enterovirus C (HEV-C117) identified in a child with community-acquired pneumonia. J Virol. 2012;86:10888–10889. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01721-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daleno C, Piralla A, Usonis V, Scala A, Ivaskevicius R, Baldanti F, Principi N, Esposito S. Novel human enterovirus C infection in child with community acquired pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1913–1915. doi: 10.3201/eid1811.120321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunson RN, Collins TC, Carman WF. Real-time RT-PCR detection of 12 respiratory viral infections in four triplex reactions. J Clin Virol. 2005;33:341–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piralla A, Fiorina L, Daleno C, Esposito S, Baldanti F. Complete genome characterization of enterovirus 104 circulating in Northern Italy shows recombinant origin of the P3 region. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiveljung-Lindell A, Rotzen-Ostlund M, Gupta S, Ullstrand R, Grillner L, Zweygberg-Wirgart B, Allander T. Development and implementation of a molecular diagnostic platform for daily rapid detection of 15 respiratory viruses. J Med Virol. 2009;81:167–175. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Leer-Buter CC, Poelman R, Borger R, Niesters HG. Newly identified enterovirus c genotypes, identified in the Netherlands through routine sequencing of all enteroviruses detected in clinical materials from 2008 to 2015. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2306–2314. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00207-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang Z, Tsatsral S, Liu C, Li L, Ren L, Xiao Y, Xie Z, Zhou H, Vernet G, Nymadawa P, Shen K, Wang J. Respiratory infection with enterovirus genotype C117, China and Mongolia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1075–1077. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.131596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 Phylogenetic trees constructed based on 5’UTR, VP4, VP2, VP3, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D and 3’UTR sequences by the maximum-likelihood method in MEGA 7.0. The isolate from the present study is indicated by a black filled circle. (TIFF 1350 kb)