Abstract

To investigate canine kobuvirus (CaKoV) infection, fecal samples (n = 59) were collected from dogs with or without diarrhea (n = 21 and 38, respectively) in the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 2012. CaKoV infection was detected in four diarrheic samples (19.0 %) and five non-diarrheic samples (13.2 %). All CaKoV-positive dogs with diarrhea were found to be infected in mixed infections with canine distemper virus and canine parvovirus or canine adenovirus. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of CaKoV in dogs with and without diarrhea. By phylogenetic analysis based on partial 3D genes and complete genome sequences, the Korean isolates were found to be closely related to each other regardless of whether they were associated with diarrhea, and to the canine kobuviruses identified in the USA and UK. This study supports the conclusion that CaKoVs from different countries are not restricted geographically and belong to a single lineage.

Keywords: Canine kobuvirus, Complete sequence, Phylogenetic analysis

Acute gastroenteritis is an important cause of death in humans and animals worldwide. The majority of acute gastroenteritis cases are caused by viruses, bacteria, and parasites; however, viruses are the predominant factor. A relatively new genus of emerging viruses of the family Picornaviridae, Kobuvirus, has been established recently [1], and members of this genus have been reported to cause enteric infections in a wide variety of mammals, including humans, cattle, pigs, sheep, dogs, bats, and rodents [2–10]. However, their role as a primary pathogen remains unclear. The genus Kobuvirus formerly consisted of two officially recognized species, namely Aichi virus (AiV) and Bovine kobuvirus [2, 11], and a candidate species, Porcine kobuvirus [12]. These species were recently renamed as Aichivirus A, B and C, respectively [1].

Canine kobuvirus (CaKoV) was first detected in the stools of dogs with acute gastroenteritis in 2011 in the USA [6, 9], thus indicating that companion animals can be infected by kobuviruses. Since this first identification, CaKoV has also been detected in the UK [13] and in Italy [14]. In addition, studies showing an association of CaKoV infection with enteric disease in dogs are limited. To date, several studies have described CaKoV detection in dogs with or without diarrhea; however, no epidemiological study has been conducted on this topic in the Republic of Korea (ROK). Therefore, the present study was performed to investigate CaKoV infection, phylogenetic comparisons between Korean CaKoV and other kobuviruses, and any association between CaKoV infection and diarrhea in dogs.

To investigate the correlation of prevalence of CaKoV with age and stool conditions, 59 stool samples were collected from dogs with or without diarrhea (n = 21 and 38, respectively), from different regions of the ROK from January 2011 to December 2012. The stool samples were collected from dogs aged less than 2 years and submitted to the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency (QIA). The samples were cultured on nutrient media by using a standard procedure; no significant bacterial pathogens were found. The samples were stored in a sample box, frozen at −80 °C until required for testing, and processed as described previously [15]. For virus isolation, Vero cells were inoculated with the stool sample and serial passages of Vero cells were performed. However, no cytopathic effects were observed in the cultured cells.

Stool samples were resuspended by vigorous vortexing in PBS at a concentration of approximately 1 g/mL. The suspensions were then centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min to remove cellular debris. Viral RNA was extracted using TRIzol LS (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR was performed with a Maxime RT-PCR PreMix Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Gyeonggi, Korea) (iNtRON, Korea). Amplification of the 3D region of kobuvirus was performed using U1F (5′-CATGCTCCTCGGTGGTCTCA-3′) and U1R (5′-GTCCGGGTCCATCACAGGGT-3′), which are bovine kobuvirus screening primers that have been reported previously [11]. For amplification, reverse transcription was performed at 45 °C for 30 min, and pre-PCR denaturation was performed at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 60 s, 55 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 90 s. For the determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of CaKoV, sequence-specific oligonucleotides were designed on the basis of the conserved regions of published canine kobuvirus sequences (JN387133 and KC161964) (Table 1). The extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the genome were determined using a 5′/3′ RACE kit (2nd generation, Roche) and oligo (dT)15 (TaKaRa, Japan), respectively. The amplified PCR products were purified using a Mega-spin Agarose Gel DNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea) and cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The cloned plasmids were purified and sequenced using T7 and SP6 primers and an automated DNA sequencer (ABI 3130 XL Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). All nucleotide positions were confirmed by three or more independent sequencing runs in both directions. Nucleotide and putative amino acid sequence alignments were generated using BioEdit (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The CaKoV sequence generated in this study has been deposited in GenBank under accession number KF924623.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of the oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification and sequencing

| Primer name† | Nucleotide sequence (5′ → 3′) | Nucleotide position* |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo d(T)-anchor | GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGAC(T)16 | - |

| Cakobu-1F | GTAACTAAGTGTGTGCCCAATC | 110-132 |

| Cakobu-1R | GCATGCAGTGGCGTCACTAGTTG | 360-382 |

| Cakobu-2R | TTCCTCATCGCAGTGGCAATAA | 871-892 |

| Cakobu-2F | TTATTGCCACTGCGATGAGGAA | 871-892 |

| Cakobu-3R | TCAGTGGTGACGTTGTTGCCATT | 1253-1275 |

| Cakobu-3F | TGTCACCAACATCTACGGCAAT | 1234-1255 |

| Cakobu-4R | GAGCCGTTGACGGTGACCTGCA | 2018-2039 |

| Cakobu-4F | TGCAGGTCACCGTCAACGGCT | 2018-2038 |

| Cakobu-5R | CCACTGTCTTCCAGTAGGACT | 2837-2857 |

| Cakobu-5F | AGTCCTACTGGAAGACAGTGG | 2847-2867 |

| Cakobu-6R | ATGAAGAAGTTGGAGAGCATCT | 3450-3471 |

| Cakobu-6F | AGATGCTCTCCAACTTCTTCAT | 3450-3471 |

| Cakobu-7R | TTGGTGTCAGCGTCAGCGGTCA | 4221-4242 |

| Cakobu-7F | TGACCGCTGACGCTGACACCAA | 4221-4242 |

| Cakobu-8R | TATCGTGACGAGTTCACGACAG | 4929-4950 |

| Cakobu-8F | CTGTCGTGAACTCGTCACGATA | 4939-4960 |

| Cakobu-9R | TGGAGTCCTCACGCTGTTGCCA | 5954-5975 |

| Cakobu-9F | TGGCAACAGCGTGAGGACTCC | 5954-5974 |

| Cakobu-10R | GGTTGATGTTGACACCGGGTT | 6659-6679 |

| Cakobu-10F | AACCCGGTGTCAACATCAACC | 6669-6689 |

| Cakobu-11R | TAATCCAGATCATACACCTGAGA | 7325-7347 |

| Cakobu-11F | TCCTCGGTGGTCTTATTGACTA | 7211-7231 |

| Cakobu-12R | AAGAACAGTTAGAAAAG | 8275-8291 |

| Oligo(dT)15 | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | - |

† F, forward; R, reverse

*Nucleotide positions for CaKoV correspond to the submitted sequence under GenBank accession no. JN088541

The complete genomic sequence of CaKoV was compared to those of the kobuvirus reference strains in GenBank using BLAST. A phylogenetic tree of the Korean CaKoV with kobuvirus reference strains as well as other representative kobuviruses based on the nucleotide and amino acid alignments was constructed by the neighbor-joining method and Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA version 4.0). Bootstrap analysis was carried out using 1,000 replications, and the phylogenetic tree was visualized using Treeview [16].

All samples were also screened for canine parvovirus (CPV), canine distemper virus (CDV), canine adenovirus (CAdV), and canine coronavirus (CCV) using a commercial detection kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea) as described previously [17, 18].

Of the 59 samples collected from dogs with and without diarrhea, nine (15.2 %) were positive for CaKoV by RT-PCR, and its prevalence in animals under the age of 4 months (67 %, 6/9) was higher than that in 2-year-old dogs (33 %, 3/9). CaKoV-positive samples were identified from dogs with (n = 4) and without diarrhea (n = 5) (Table 2). The nine CaKoV-positive stool samples were also tested for other enteric pathogens, e.g., CDV, CPV, and CAdV. Interestingly, CDV was the most common, being detected in four dogs with diarrhea and in one dog without diarrhea (Table 2). Of the concurrent infections of CaKoV with other enteric pathogens, mixed infections with two enteric pathogens (CaKoV + CDV, n = 1) and three enteric pathogens (CaKoV + CDV + CAdV, n = 2; CaKoV + CDV + CPV, n = 1) were identified in one and three dogs with diarrhea, respectively. One mixed infection (CaKoV + CPV + CDV) was found in a dog without diarrhea (Table 2). No enteric pathogens were detected in three dogs without diarrhea.

Table 2.

Summary of CaKoV and other enteric viral pathogens detected in stool samples from dogs with and without diarrhea, determined by RT-PCR

| No. | ID | Age | Clinical signs | Region | CaKoV | Mixed infections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12D049 | 3 months | Diarrhea | Gyeonggi | + | CDV, CAdV |

| 2 | 12D113 | 2 months | Asymptomatic | Gyeonggi | + | - |

| 3 | 12D188 | 1 year | ″ | Seoul | + | - |

| 4 | 12D232 | 1 year | ″ | Chonbuk | + | - |

| 5 | 12D290-1 | 4 months | Diarrhea | Gyeonggi | + | CDV, CAdV |

| 6 | 12D290-2 | 4 months | Diarrhea | Gyeonggi | + | CDV |

| 7 | 12D290-4 | 4 months | Diarrhea | Gyeonggi | + | CDV, CPV |

| 8 | 12Q172 | 2 months | Asymptomatic | Jeonnam | + | CDV, CPV |

| 9 | 12Q179-1 | 2 years | ″ | Gyeonggi | + | - |

CDV, canine distemper virus; CAdV, canine adenovirus; CPV, canine parvovirus

In this study, CaKoV was detected in both diarrheic and non-diarrheic samples. Our observation indicated that there was no significant difference in the prevalence of CaKoV in dogs with and without diarrhea. These results imply that CaKoV may be not associated with diarrhea because of its presence in dogs with and without diarrhea. However, in a recent study, kobuviruses were detected only in diarrheic dogs, some of which were found to be infected by CaKV alone while some had mixed infections with canine coronavirus (CCV) and/or CPV [14]. Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the association of this virus with gastroenteritis and risk factors for infection with CaKoV. Also, the infection rate of CaKoV in younger animals aged ≤4 months appeared to be higher than in adult dogs (67 % vs. 33 %, respectively). These findings support the possibility that the high susceptibility of young animals to CaKoV infections is likely due to an inefficient immune response or other intrinsic age-related factors [19].

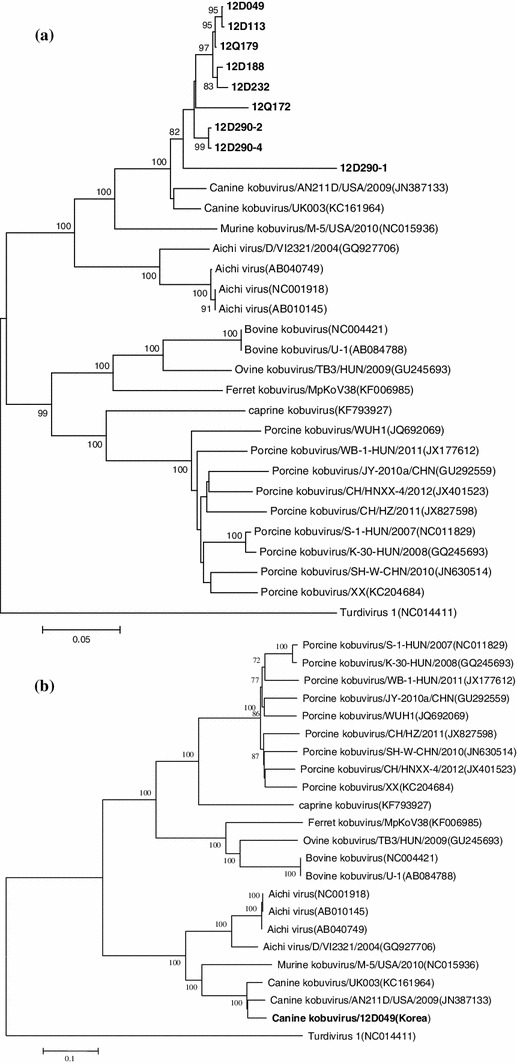

To investigate the genetic heterogeneity of CaKoV circulating in dogs in the ROK, the nine CaKoV-positive samples (four from diarrheic and five from non-diarrheic dogs) were partially sequenced. Genetic analysis of the partial 3D region showed that the CaKoVs identified in the ROK were more variable, sharing nucleotide sequence identity ranging from 85.1 to 99.8 %. In phylogenetic analysis based on a portion of the 3D region, nine kobuvirus-positive samples were closely related to each other regardless of whether they were associated with diarrhea (Fig. 1a). For further analysis, one representative kobuvirus-positive sample was selected for genomic sequencing. The complete genome sequence of Korean CaKoV 12D049 was determined and found to be 8,292 nucleotides (nt) in length, excluding the poly-A tail at its 3’ end, and a large open reading frame of 7,335 nt encoding a potential polyprotein of 2,475 amino acids was identified. Phylogenetic analysis of 12D049 together with the published sequences of kobuvirus reference stains (porcine kobuvirus, AiV, and bovine kobuvirus) revealed that 12D049 was closely related to the CaKoVs (UK003 and AN211D) that were found recently in the UK and the USA, and it was distinct from human kobuvirus (AiV) [2] and other kobuviruses reported previously [5, 10–12] (Fig. 1). 12D049 displayed a high level of similarity to UK003 and AN211D, exhibiting 98.1 % and 96.6 % homology at the nucleotide level and 93.2 % and 93.6 % at the amino acid level, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis based on a partial nucleotide sequence of the 3D region (a) and the complete genome sequence (b) of our CaKoV and other published kobuviruses with sequences available in the GenBank database. The phylogenetic tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method. One thousand bootstrap replicates were performed, and the bootstrap values are displayed above the tree branches; only bootstrap values >70 % are shown

The phylogenetic analysis based on complete genome sequences confirmed that 12D049 is closely related to AN211D and UK003, which were identified previously in the USA and the UK, respectively. Interestingly, 12D049 showed the closest genetic relationship (98.1 % nt sequence identity) to a UK isolate (UK003) detected in a diarrheic dog. This finding supports that CaKoVs from different countries are not restricted geographically and form a single lineage. Furthermore, our data revealed that 12D049 belonged to a lineage that was distinct from AiV and mouse kobuvirus (Fig. 1b). Further studies are required for the genetic characterization of CaKoVs circulating in dog populations in the ROK.

In conclusion, the present study showed that CaKoV is prevalent in dogs with and without diarrhea, and a relationship between CaKoV infection and its pathogenicity causing diarrhea was not found. Thus, further investigations are needed to determine their role as a causative agent of enteric disease in dogs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency of the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs in Anyang, ROK.

References

- 1.Adams MJ, King AMQ, Carstens EB. Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch Virol. 2013;158:2023–2030. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Tsuzuki H, Suzuki Y, Ishikawa N, Takeda N, Miyamura T, Yamazaki S. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of Aichi virus, a distinct member of the Picornaviridae associated with acute gastroenteritis in humans. J Virol. 1998;72:8408–8412. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8408-8412.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khamrin P, Maneekarn N, Peerakome S, Okitsu S, Mizuguchi M, Ushijima H. Bovine kobuviruses from cattle with diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:985–986. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.070784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuter G, Boldizsar A, Pankovics P. Complete nucleotide and amino acid sequences and genetic organization of porcine kobuvirus, a member of a new species in the genus Kobuvirus, family Picornaviridae. Arch Virol. 2009;154:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuter G, Boros A, Pankovics P, Egyed L. Kobuvirus in domestic sheep, Hungary. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;5:869–870. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Victoria JG, Wang C, Jones M, Fellers GM, Kunz TH, Delwart E. Bat guano virome: predominance of dietary viruses from insects and plants plus novel mammalian viruses. J Virol. 2010;84:6955–6965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00501-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Pesavento PA, Shan T, Leutenegger CM, Wang C, Delwart E. Viruses in diarrhoeic dogs include novel kobuviruses and sapoviruses. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2534–2541. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034611-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MH, Jeoung HY, Lim JA, Song JY, Song DS, An DJ. Kobuvirus in South Korean black goats. Virus Genes. 2012;45:186–189. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Dubovi EJ, Qaisar N, Henriquez JA, Medina J, Shields S, Lipkin WI. Characterization of a canine homolog of human Aichivirus. J Virol. 2011;85:11520–11525. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05317-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phan TG, Kapusinszky B, Wang C, Rose RK, Lipton HL, Delwart EL. The fecal viral flora of wild rodents. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita T, Ito M, Kabashima Y, Tsuzuki H, Fujiura A, Sakae K. Isolation and characterization of a new species of kobuvirus associated with cattle. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:3069–3077. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuter G, Boldizsar A, Kiss I, Pankovics P. Candidate new species of kobuvirus in porcine hosts. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1968–1970. doi: 10.3201/eid1412.080797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmona-Vicente N, Buesa J, Brown PA, Merga JY, Darby AC, Stavisky J, Sadler L, Gaskell RM, Dawson S, Radford AD. Phylogeny and prevalence of kobuviruses in dogs and cats in the UK. Vet Microbiol. 2013;164:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Martino B, Di Felice E, Ceci C, Di Profio F, Marsilio F. Canine kobuviruses in diarrhoeic dogs in Italy. Vet Microbiol. 2013;166:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung JY, Kim SH, Kim YH, Lee MH, Lee KK, Oem JK. Detection and genetic characterization of feline kobuviruses. Virus Genes. 2013;47:559–562. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0953-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon SH, Jeong W, Kim HJ, An DJ. Molecular insights into the phylogeny of canine parvovirus 2 (CPV-2) with emphasis on Korean isolates: a Bayesian approach. Arch Virol. 2009;154:1353–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0444-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo GH, Jho YS, Bak EJ. Canine distemper virus infection in fennec fox (Vulpes zerda) J Vet Med Sci. 2010;72:1075–1079. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry AF, Ribeiro J, Alfieri AF, Van Der Poel WH, Alfieri AA. First detection of kobuvirus in farm animals in Brazil and The Netherlands. Infecti Genet Evol. 2011;11:1811–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]