Abstract

Feline calicivirus (FCV) is a common cause of upper respiratory tract disease in cats and is associated with interstitial pneumonia, oral ulceration and polyarthritis. Recently, outbreaks have involved a highly virulent FCV that leads to multisystemic signs. Virus isolation and conventional RT-PCR are the most common methods used for FCV diagnosis. However, real-time RT-PCR offers a rapid, sensitive, specific and easy tool for nucleic acid detection. The objective of this study was to design a TaqMan probe-based, real-time RT-PCR assay for detection of FCV. It was determined in our previous study that the first 120 nucleotides of the 5′ region of the genome are highly conserved among FCV isolates. Primers and a probe specific for this region were designed for a real-time RT-PCR assay to detect FCV. Initial validation was done using 15 genetically diverse isolates. Also, 122 samples were tested by the new assay and virus isolation. The real-time RT-PCR assay was as sensitive and specific as virus isolation and was far more rapid. This real-time RT-PCR assay targeting the conserved 5′ region of the genome is a fast, economical and accurate method for detection of FCV.

Keywords: Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction, Feline Immunodeficiency Virus, Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay, Capsid Protein Gene, Feline Calicivirus

Introduction

Feline calicivirus (FCV) is an important pathogen of cats and is commonly associated with upper respiratory tract disease [8]. Other clinical manifestations may include lingual ulcers [23], chronic gingivitis, pharyngitis [31], chronic stomatitis [30], pneumonia [30], acute arthritis [6, 21], jaundice with virulent systemic FCV disease and multi-organ failure [1, 15, 22, 27], and death from in utero infection [7]. However, existence of an asymptomatic carrier state is not uncommon, with up to 20–25% of apparently healthy cats shedding the virus [32, 33]. In addition to its isolation in domestic cats, FCV has been isolated from exotic felids, including captive cheetahs [25]. Antibodies specific for FCV have also been detected in free-ranging species including Namibian cheetahs [17], free-ranging African lions and mountain lions [14, 20], and Florida panthers [24].

A member of the genus Vesivirus, family Caliciviridae, FCV is a non-enveloped virus with a 7.7-kb single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome [5]. Nucleotides 1–19 of the genome are untranslated, followed by three open reading frames (ORF): ORF1 (nucleotides 20–5,305) encodes a large polyprotein that includes the viral polymerase; ORF2 (nucleotides 5,314 to 7,317–7,326) encodes the major structural capsid protein VP1; and ORF3 (nucleotides 7,617–7,626 to 7,634–7,643) encodes the minor structural protein VP2, with an unknown function [3, 4, 10, 13, 19, 28]. The FCV genome has relatively high genetic variability; however, genetic analysis of a variety of isolates from a previous investigation has shown that the first 52 nucleotides in all known sequences are 100% conserved. Nucleotides 101–120 of the genome were also found to be highly conserved among FCV isolates [1, 10]. Virus isolation and conventional reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are the most common methods used for FCV diagnosis [9, 29]. Real-time RT-PCR has been developed for FCV; however, previous attempts to develop real-time RT-PCR for FCV have used SYBR green instead of a specific hybridization probe [12, 26, 34]. One study employed a sequence-specific probe targeting a 67-bp product from ORF1 (nucleotides 2,466–2,532 from accession number M86379), but the sequence of the targeted probe was variable among the FCV isolates [11].

The present study describes the evaluation, optimization and validation of a real-time RT-PCR assay for detecting and quantifying FCV using a specific hybridization probe. The test was able to detect 15 diverse FCV isolates that had been genetically characterized, including virulent systemic isolates. Validation was done with 102 clinical samples and 20 samples from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) cats. Results obtained by real-time RT-PCR were compared to those of virus isolation (the gold standard assay). The method was demonstrated to be rapid, specific, reproducible and as sensitive as virus isolation.

Materials and methods

Viruses and bacteria

Six previously genetically identified FCV field isolates [1] were used as well as an additional nine genetically characterized isolates obtained during the study (Table 1) (Clinical Virology Laboratory, University of Tennessee, Knoxville [UTK]). Other feline pathogens were also tested by this assay to evaluate its specificity, including Bartonella vinsonii, Leptospira grippotyphosa, Chlamydophila felis, feline coronavirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline herpesvirus and feline panleukopenia virus, all generous gifts from the Clinical Virology Laboratory (UTK).

Table 1.

Feline calicivirus strains used in this study and their GenBank accession numbers

| Virus name | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|

| UTCVM-NH1a | AY560113 |

| UTCVM-NH2a | AY560114 |

| UTCVM-NH3a | AY560115 |

| UTCVM-H1a | AY560116 |

| UTCVM-H2a | AY560117 |

| USDAa | AY560118 |

| UTCVM-NH4b | AY996855 |

| UTCVM-NH5b | AY996856 |

| UTCVM-NH6b | AY996857 |

| UTCVM-NH7b | AY996858 |

| UTCVM-NH8b | AY996859 |

| UTCVM-NH9b | AY996860 |

| UTCVM-NH10b | AY996861 |

| UTCVM-NH11b | AY996862 |

| UTCVM-NH12b | AY996863 |

aPreviously published [1]

bCurrent study

Clinical samples

A total of 102 clinical samples from cats showing upper respiratory disease were submitted to the Clinical Virology Laboratory (UTK) for viral diagnostics. These samples were collected from 2004 to 2008 and were from several states within the USA. Twenty SPF cat samples were also included in the study (known negative population). Duplicate swabs from nasal and/or conjunctival and/or oro-pharyngeal sites were collected from each animal; one was placed in transport medium for virus isolation, and one was stored dry for nucleic acid extraction. Samples were stored at 4°C for a maximum of 72 h after receipt until processed.

Virus propagation and isolation

Crandell-Reese feline kidney (CRFK) cells were used for virus isolation. The CRFK cells were grown with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Cambrex Bioscience Walkersville, USA) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, USA) with standard concentrations of penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B (Cambrex Bioscience Walkersville). Monolayers of CRFK cells at 60–80% confluency, grown in 25- or 75-cm2 flasks, were inoculated with 1 ml of vortexed transport media containing the swab and observed daily for 7 days for cytopathic effect (CPE). Cell cultures were maintained until 50–70% CPE developed, followed by collection of cells for virus identification by antigen detection using monoclonal FCV1-43 antibodies (Custom Monoclonals International, USA). Samples with no CPE after two passages were reported as negative.

Nucleic acid extraction

The QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to extract RNA from all samples as well as nucleic acids from other feline pathogens. This kit was ideal for the purification of both RNA and DNA.

Conventional PCR and genetic analysis

Genetic analysis of six FCV isolates was done as described previously [1]. Genetic analysis of the major capsid protein gene of the nine additional isolates was performed with the FCVCAPFOR and FCVCAPREV primer pair as described previously (Table 2) [1, 2]. Sequencing of the purified PCR products was done at the Molecular Biology Resources Service (UTK) using an ABI prism dye terminator cycle sequencing reaction kit and ABI 373 DNA. Phylogenetic tree construction and sequence distances were performed using the MegAlign program with the Jotun Hein align method, available in the Lasergene package (DNAStar, USA).

Table 2.

Sequences of the primers and the probe used in this study

| Oligonucleotide (primer) | Oligonucleotide position in the genomea | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| FCV-forward (real-time) | 1–21 | 5′-GTAAAAGAAATTTGAGACAAT-3′ |

| FCV-reverse (real-time) | 120–104 | 5′-TACTGAAGWTCGCGYCT-3′ |

| FCV-probe (real-time) | 26–49 | 5′-FAM-CAAACTCTGAGCTTCGTGCTTAAA-TAMRA-3′ |

| FCVCAPFORb | 5,286–5,307 | 5′-TACACTGTGATGTGTTCGAAGT-3′ |

| FCVCAPREVb | 7,547–7,567 | 5′-GTGTATGAGTAAGGGTCAACC-3′ |

cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR

Synthesis of cDNA was done using SS II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using random primers (Invitrogen) and 5 μl undiluted nucleic acid. The real-time RT-PCR method targeted a 120-bp fragment located at nucleotides 1–120 of the FCV genome (5′ untranslated region; part of ORF1). Primers and probe-specific sequences are shown in Table 2. Five μl of the synthesized cDNA was amplified in 25-μl total volume reactions using OmniMix HS (ready-to-use, lyophilized universal PCR reagent beads containing hot start Taq [TaKaRa Bio, Japan]), containing 200 μM dNTPs, 4 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 200 nM probe, and 300 nM of each primer. The mixture was carried out in the Cepheid SmartCycler II System (Cepheid, USA) with the following parameters: an initial activation step for the hot start Taq polymerase at 95°C for 2 min, then 45 three-step cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 56°C for 60 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. A threshold value of more than 40 was considered a negative result. DNase/RNase-free water was used as a negative control.

Preparation of standard RNA and standard curve production

cDNA from an FCV USDA strain was amplified by conventional PCR with primers used for the RT-PCR assay. The fragment was purified from the gel and ligated into pCr 2.1 (TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen). E. coli (One Shot INV F, Invitrogen) was transformed with the recombinant, and a positive colony was amplified in LB-medium containing ampicillin. The plasmids were purified (SNAP MiniPrep Kit, Invitrogen), linearized (HindIII, Fisher Scientific, USA) and quantified (DynaQuant Fluorometer with Hoechst dye 33528, Fisher Scientific). The identity and orientation of the cloned product was verified by sequencing (Molecular Biology Resources Service, UTK). One μg of the linearized plasmid was used to perform an in vitro transcription with T7 polymerase at 37°C for 2 h (AmpliCap T7 High Yield Message Maker Kit, Epicentre, USA). After digestion with RNase-free DNase, the resulting RNA transcripts were purified with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN). The RNA transcripts were eluted in nuclease-free water, and the RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometric analysis at OD 260/280. The number of RNA copies in the sample was estimated based on the molecular weight of the RNA standard and the RNA concentration. Tenfold serial dilutions of RNA stock were prepared in DNase- and RNase-free water, and aliquots were made and frozen immediately at −70°C. Each aliquot was used only once for real-time RT-PCR. Dilutions of standard RNA were tested by real-time PCR, and a standard curve was generated by the Smart Cycler II software.

Evaluation of real-time RT-PCR sensitivity and specificity

Fifteen genetically characterized FCV strains were used for preliminary sensitivity determination. The standard curve was used to evaluate the absolute sensitivity of the assay by determining the minimum number of RNA templates detectable. The sensitivity of the real time RT-PCR assay was also compared to the sensitivity of virus titration for five of the genetically characterized FCV isolates [16]. The ability of the real-time RT-PCR assay to detect viral RNA from each viral titration endpoint dilution and one tenfold dilution past the endpoint was evaluated. Other feline pathogens (mentioned previously) were tested for specificity determination. Also, results for 122 clinical samples (including 20 SPF cats) were compared to virus isolation.

Results

Sensitivity of FCV real-time RT-PCR

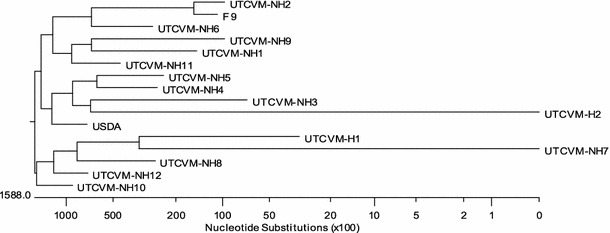

Capsid gene sequences of the characterized feline calicivirus isolates used in this study (Table 1) were determined. The nucleotide sequences of the capsid protein gene demonstrated the significant diversity of the FCV strains used (Fig. 1). The assay was able to detect all 15 FCV isolates, including two isolates associated with virulent systemic disease, UTCVM-H1 and UTCVM-H2 [1].

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of the capsid protein genes of 15 FCV isolates used in the study and the F-9 strain (GenBank accession number M86379)

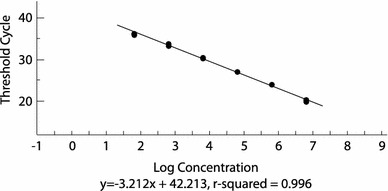

Tenfold serial dilutions of the FCV standard RNA produced a linear assay over six dilutions between 10−4 to 10−9 with a correlation coefficient of 0.996 (Fig. 2). The linearity and co-efficiency indicate that the assay is reproducible and sensitive. Based on the precision of the assay, the theoretical limit of detection (LOD) was estimated to be approximately 70 copies of the purified RNA (Fig. 2). Sensitivity of the new assay was also directly compared to the gold standard assay (virus isolation) [18] results using clinical samples (pharyngeal and/or conjunctival swabs). Of the 102 samples from the clinically diseased cats, 30 were positive by virus isolation. These 30 samples had a CT value of less than 40, which is considered positive by the new assay, showing 100% sensitivity (no false negative results) (Table 3). The real-time RT-PCR assay was determined to be at least as sensitive as virus isolation based on the results obtained from the titration experiment. Viral RNA was detected in the endpoint dilutions of all five isolates tested (CT values ranging from 37 to 40). RNA was also detected in dilutions past the titration endpoints for three of the five isolates, but CT values exceeded 40 and were considered negative.

Fig. 2.

Standard curve obtained with tenfold serial dilutions from 10−4 to 10−9 of standard RNA (generated from the threshold cycle values) plotted against the logarithmic concentration of the serial dilutions

Table 3.

Comparison of quantitative RT-PCR with virus isolation for detection of FCV

| Virus isolation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Real-time RT-PCR | ||

| Positive | 30 | 0 |

| Negative | 0 | 72 |

| Total | 30 | 72 |

Specificity of FCV real-time RT-PCR

The assay had no cross-reactivity to nucleic acid of the other feline pathogens used for specificity evaluation. These pathogens included Bartonella vinsonii, Leptospira grippotyphosa, Chlamydophila felis, feline coronavirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline herpesvirus and feline panleukopenia virus.

Samples from the 20 SPF cats were negative by the new assay and by virus isolation. Moreover, 72 clinical samples that were negative by virus isolation were also negative by real-time RT-PCR, showing 100% specificity (no false positive results) (Table 3).

Discussion

Upper respiratory tract disease in cats is not uncommon, and the clinical signs are similar to those seen with other feline pathogens such as feline herpesvirus. Differential diagnosis of these agents is necessary for appropriate treatment and control. Direct detection of the viral antigen by the immunofluorescence antibody technique (IFA), virus isolation, or molecular detection by conventional and nested PCR is used to detect FCV in diagnostic samples. However, antigen detection, while rapid and inexpensive, has relatively low sensitivity. Virus isolation is the gold standard but may require several days to 2 weeks for completion. Likewise, conventional and nested RT-PCR assays have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity [16, 29], but these procedures are considered more time-consuming than the TaqMan real-time RT-PCR.

Real-Time PCR has higher sensitivity than conventional PCR due to the use of a fluorescent-labeled probe for detection of amplification products and requires no post-amplification evaluation of PCR products. Elimination of post-amplification evaluation of samples reduces the likelihood of laboratory and sample contamination. This technique also allows quantitation of the amount of virus in the sample, aiding interpretation. Most previous reports of real-time PCR for detection of FCV were limited to the use of SYBR green dye; however, using a specific molecular probe increases the specificity of the assay and provides opportunities for developing multiplex PCR for other feline respiratory tract pathogens [12, 26, 34]. Another assay utilized the hybridization probe, but the sequence of the targeted probe was variable among the FCV isolates [11]. IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, Maine, USA, offers a real-time probe-based assay, but no published data are available. The determination of the sensitivity and specificity of the previous assays was done primarily using viruses isolated in cell culture and a limited number of clinical samples.

Genetic detection offers increased sensitivity and fast turn-around but has been difficult with FCV due to genetic variation of different strains, leading to false negative results. The nucleotide sequence of the capsid protein gene of the FCV isolates used in the study shows significant genetic variation, which is in agreement with previous studies (Fig. 1) [1, 10]. Identification of a conserved genetic region has been challenging due to limited sequence data of the complete genome of different FCV isolates as well as the high variability of the genetic regions that have been characterized. Previous investigations, including our analysis of six different isolates, have identified a conserved area in the 5′ region of the FCV genome [1, 10]. However, these regions are not conserved among other vesiviruses (data not shown). This region was the basis for the selection of primers and the probe for the real-time PCR assay.

The assay we developed proved to be a sensitive and specific method for FCV detection. Approximately 70 copies of the viral genome could be detected. A variety of FCV variants were detectable, while cross-reactivity with other feline pathogens did not occur. Detection by this method was comparable to virus isolation; in addition, mixed infections with pathogens could be defined. For example, mixed infection with feline herpesvirus was identified by PCR in several clinical samples (data not shown). The assay was performed on clinical samples to detect the presence or absence of FCV. Although the developed assay has the capability to allow calculation of the precise viral load in the biological samples, the application of these data is limited by the lack of objective clinical scoring and the inability to standardize the procedure of sample collection for diagnostic purposes.

Feline calicivirus was found in 30 of 102 clinically diseased cats, with a positive percentage of 29.4%; however, determination of the prevalence of FCV in the general feline population requires a more extensive survey that includes healthy and diseased cats.

In summary, the real-time RT-PCR we developed proved to have high sensitivity and specificity for FCV. This assay provides a rapid, economical, and accurate diagnostic tool for identification of FCV infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Misty Bailey and Dr. Leon Potgieter for their critical review of the manuscript and Ms. Anik Vasington for her help with the figures.

References

- 1.Abd-Eldaim M, Potgieter L, Kennedy M. Genetic analysis of feline caliciviruses associated with a hemorrhagic-like disease. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:420–429. doi: 10.1177/104063870501700503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baulch-Brown C, Love D, Meanger J. Sequence variation within the capsid protein of Australian isolates of feline calicivirus. Vet Microbiol. 1999;68:107–117. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter MJ. Feline calicivirus protein synthesis investigated by Western blotting. Arch Virol. 1989;108:69–79. doi: 10.1007/BF01313744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter MJ, Milton ID, Turner PC, et al. Identification and sequence determination of the capsid protein gene of feline calicivirus. Arch Virol. 1992;122:223–235. doi: 10.1007/BF01317185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter MJ, Milton ID, Meanger J, et al. The complete nucleotide-sequence of a feline calicivirus. Virology. 1992;190:443–448. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91231-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson S, Bennett D, Carter SD, et al. Acute arthritis of cats associated with feline calicivirus infection. Res Vet Sci. 1994;56:133–143. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis TM. Jaundice in a Siamese cat with in utero feline calicivirus infection. Aust Vet J. 1981;57:383–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1981.tb00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaskell RD, Dawson S. Feline respiratory diseases. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 2. St. Louis: Saunders; 1998. pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillespie JH, Judkins AB, Kahn DE. Feline viruses. 13. The use of the immunofluorescent test for the detection of feline picornaviruses. Cornell Vet. 1971;61:172–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glenn M, Radford AD, Turner PC, et al. Nucleotide sequence of UK and Australian isolates of feline calicivirus (FCV) and phylogenetic analysis of FCVs. Vet Microbiol. 1999;67:175–193. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helps C, Harbour D. Detection of nucleotide polymorphisms in feline calicivirus isolates by reverse transcription PCR and a fluorescence resonance energy transfer probe. J Virol Methods. 2003;109:261–263. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(03)00051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helps C, Lait P, Tasker S, et al. Melting curve analysis of feline calicivirus isolates detected by real-time reverse transcription PCR. J Virol Methods. 2002;106:241–244. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(02)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbert TP, Brierley I, Brown TDK. Detection of the ORF3 polypeptide of feline calicivirus in infected cells and evidence for its expression from a single, functionally bicistronic, subgenomic mRNA. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:123–127. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-1-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann-Lehmann R, Fehr D, Grob M, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to feline parvovirus, calicivirus, herpesvirus, coronavirus, and immunodeficiency virus and of feline leukemia virus antigen and the interrelationship of these viral infections in free-ranging lions in east Africa. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:554–562. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.5.554-562.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurley KF, Pesavento PA, Pedersen NC, et al. An outbreak of virulent systemic feline calicivirus disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224:241–249. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsilio F, Di Martino B, Decaro N, et al. A novel nested PCR for the diagnosis of calicivirus infections in the cat. Vet Microbiol. 2005;105:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munson L, Marker L, Dubovi E, et al. Serosurvey of viral infections in free-ranging Namibian cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) J Wildl Dis. 2004;40:23–31. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-40.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy FA, Gibbs EPJ, Horzinek MC, et al. Veterinary virology. 3. St. Louis: Elsevier Science Technology Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neill JD, Reardon IM, Heinrikson RL. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the capsid protein gene of feline calicivirus. J Virol. 1991;65:5440–5447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5440-5447.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul-Murphy J, Work T, Hunter D, et al. Serologic survey and serum biochemical reference ranges of the free-ranging mountain lion (Felis concolor) in California. J Wildl Dis. 1994;30:205–215. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-30.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen NC, Laliberte L, Ekman S. A transient febrile limping syndrome of kittens caused by 2 different strains of feline calicivirus. Feline Pract. 1983;13:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen NC, Elliott JB, Glasgow A, et al. An isolated epizootic of hemorrhagic-like fever in cats caused by a novel and highly virulent strain of feline calicivirus. Vet Microbiol. 2000;73:281–300. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Povey RC, Hale CJ. Experimental infections with feline caliciviruses (picornaviruses) in specific-pathogen-free kittens. J Comp Pathol. 1974;84:245–256. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(74)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roelke ME, Forrester DJ, Jacobson ER, et al. Seroprevalence of infectious disease agents in free-ranging Florida panthers (Felis concolor coryi) J Wildl Dis. 1993;29:36–49. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-29.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabine M, Hyne RHJ. Isolation of a feline picornavirus from cheetahs with conjunctivitis and glossitis. Vet Rec. 1970;87:794–796. doi: 10.1136/vr.87.26.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scansen BA, Wise AG, Kruger JM, et al. Evaluation of a p30 gene-based real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of feline caliciviruses. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:135–138. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18<135:EOAPGR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schorr-Evans EM, Poland A, Johnson WE, et al. An epizootic of highly virulent feline calicivirus disease in a hospital setting in New England. J Feline Med Surg. 2003;5:217–226. doi: 10.1016/S1098-612X(03)00008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sosnovtsev SV, Green KY. Identification and genomic mapping of the ORF3 and VPg proteins in feline calicivirus virions. Virology. 2000;277:193–203. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sykes JE, Studdert VP, Browning GF. Detection and strain differentiation of feline calicivirus in conjunctival swabs by RT-PCR of the hypervariable region of the capsid protein gene. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1321–1334. doi: 10.1007/s007050050378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tenorio AP, Franti CE, Madewell BR. Chronic oral infections of cats and their relationship to persistent oral carriage of feline calici, immunodeficiency, or leukemia viruses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;29:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(91)90048-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson RR, Wilcox GE, Clark WT, et al. Association of calicivirus infection with chronic gingivitis and pharyngitis in cats. J Small Anim Pract. 1984;25:207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1984.tb00470.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wardley RC, Gaskell RM, Povey RC. Feline respiratory viruses—their prevalence in clinically healthy cats. J Small Anim Pract. 1974;15:579–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1974.tb06538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weeks ML, Gallagher A, Romero CH. Sequence analysis of feline caliciviruses isolated from the oral cavity of clinically normal domestic cats (Felis catus) in Florida. Res Vet Sci. 2001;71:223–225. doi: 10.1053/rvsc.2001.0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelm S, Truyen U. Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay to detect a broad range of feline calicivirus isolates. J Virol Methods. 2006;133:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]