Abstract

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) in Thailand was first detected in 2015. We performed a retrospective investigation of the presence of PDCoV in intestinal samples collected from piglets with diarrhea in Thailand from 2008 to 2015 using RT-PCR. PDCoV was found to be present as early as February 2013. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that all PDCoV variants from Thailand differ from those from other countries and belong to a novel group of PDCoV that is separate from the US and Chinese PDCoV variants. Evolutionary analysis suggested that the Thai PDCoV isolates probably diverged from a different ancestor from that of the Chinese and US PDCoV isolates and that this separation occurred after 1994.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00705-017-3331-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Amino Acid Level, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus, Intestinal Sample, Retrospective Investigation, Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) causes an enteric disease in pigs that is characterized by diarrhea and is clinically similar to porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) and transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) [4]. PDCoV, a recently emerged RNA virus of the family Coronaviridae, genus Deltacoronavirus, was first reported in Hong Kong in 2012 during an investigation to identify novel coronaviruses [14]. In February 2014, PDCoV was first detected in pigs with clinical diarrheal disease on farms in Ohio, USA. A subsequent retrospective investigation reported revealed that PDCoV had been present in the US as early as 2013 [11]. PDCoV has since been identified in Canada, China, South Korea and Laos [1, 6, 9]. In Thailand, PDCoV was first reported in 2015 [10]. However, it is unknown whether PDCoV was present in Thailand prior to 2015. We therefore conducted a retrospective study to detect the presence of PDCoV intestinal samples from Thailand that had been submitted for the identification of enteric diseases. Positive samples were subjected to full-length genome characterization followed by genetic analyses to compare Thai strains of PDCoV to those from other countries and to investigate the genetic similarity and the evolutionary relationships among them.

A total of 241 intestinal samples were assayed for the presence of PDCoV using RT-PCR. Intestinal samples were from 3- to 4-day-old piglets with clinical diarrheal disease collected from January 2008 to December 2015 and stored at -80 °C. The presence of other viruses causing enteric disease, including porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, and transmissible gastroenteritis virus was detected using RT-PCR. In brief, viral RNA was extracted from the samples using NucleoSpin RNAVirus (Macherey-Nagel Inc., PA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the extracted RNA using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). PCR amplification was performed on cDNA using specific primers for the N gene of PDCoV, the spike gene of PEDV, and the N gene of TGEV as described previously [5, 10, 12].

Samples positive for PDCoV were then subjected to full-length genome sequence characterization. Twenty-six pairs of primers were used to amplify the different regions of PDCoV [8]. PCR amplification was performed using Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR products were purified using a NucleoSpin Plasmid kit (Macherey-Nagel Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA). The 5′- and 3′-terminal regions were determined by using a kit for rapid amplification of 5′ and 3′ cDNA ends (5′ and 3′-RACE, Clontech, Japan). Sequencing was performed at First BASE Laboratory SdnBhd (Selangor, Malaysia) using an ABI Prism 3730XL DNA sequencer.

The full-length PEDV genome sequence was assembled, and nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were aligned and analyzed using the CLUSTALW program [13]. The percentages of homology between the sequences at the nucleotide and amino acid levels were calculated. To investigate its evolutionary relationships to foreign PDCoV strains and estimate the divergence time of PDCoV in Thailand, phylogenetic analysis of the full-length nucleotide sequence of the PDCoV isolate collected in this study, together with 21 other PDCoV isolate sequences (Supplementary Table 1), was performed using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (BMCMC) method implemented in the program BEAST v1.8.3 [2, 3]. A BEAST run was performed based on the GTR+G+I model with a coalescent Bayesian skyline tree prior and a clock model for each analysis using 200 million generations with sampling of every 10,000 generations and the first 10% discarded as burn-in. Tracer v1.6 was used to confirm that post-burn-in trees yielded an effective sample size (ESS) of >200 for all parameters. The resulting tree was viewed and generated in FigTree v1.4.2.

The results of testing for PDCoV, PEDV, and TGEV in intestinal samples are shown in Table 1. Of 241 intestinal samples tested, all were negative for TGEV. Fifteen samples (6.22%) were positive for PDCoV. One sample that was collected in February 2013 was PDCoV positive. The sample was from a farm in Ratchaburi, a province in the western region of Thailand where pig density is high. Interestingly, the sample was also positive for PEDV. Four samples collected in 2014 from two farms in Ratchaburi were PDCoV positive. On one of these farms, samples from 2013 and 2014 were positive for both PDCoV and PEDV. In 2015, PDCoV was detected in eight samples collected from five farms located in Ratchaburi, Saraburi, Lopburi and Chonburi. These four provinces contain three major swine-producing areas of Thailand. These results suggest that PDCoV is widespread throughout Thailand. It is noteworthy that 144 samples (59.75%) were positive for PEDV and that samples that were positive for PDCoV were also positive for PEDV. The results suggest the presence of mixed infections with PEDV and PDCoV in pigs. The production records of the herd in which PDCoV was first detected showed that there had been three diarrhea outbreaks during 2014 and 2015, and both PEDV and PDCoV were detected. In three diarrhea outbreaks, the pre-weaning mortality rate was 56.9, 52.1 and 65.3%, respectively. However, we were unable to define the relationship between PEDV and PDCoV regarding to the primary or secondary causes of the diarrhea outbreaks. Whether co-infection with these viruses would necessitate more-complex control methods or would result in more-frequent, repetitive outbreaks requires further investigation.

Table 1.

Samples tested for porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) by PCR in Thailand in 2008-2015

| Year | Region | Province | Number of samples | PDCoV positive (%) | PEDV positive (%) | TGEV positive (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | West | Rachaburi | 24 | 1 (4.17%) | 22 (91.67%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nakhon Pathom | 14 | 0 (0%) | 10 (71.43%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Middle | Saraburi | 10 | 1 (10%) | 10 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Lopburi | 6 | 2 (33.33%) | 6 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| East | Chonburi | 11 | 5 (45.45%) | 11 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Chachoengsao | 2 | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Northeast | Nakhon Ratchasima | 8 | 0 (0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Buriram | 13 | 0 (0%) | 13 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2014 | West | Ratchaburi | 12 | 4 (33.33%) | 6 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nakhon Pathom | 3 | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Middle | Saraburi | 4 | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| East | Chonburi | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2013 | West | Nakhon Pathom | 4 | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ratchaburi | 6 | 2 (33.33%) | 4 (66.67%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| East | Chonburi | 7 | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2012 | West | Ratchaburi | 4 | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Middle | Saraburi | 2 | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| East | Rayong | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2011 | West | Ratchaburi | 68 | 0 (0%) | 9 (13.24%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nakhon Pathom | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Middle | Saraburi | 9 | 0 (0%) | 5 (55.56%) | 0 (0%) | |

| East | Chonburi | 5 | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Northeast | Nakhon Ratchasima | 3 | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.33%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2010 | West | Ratchaburi | 9 | 0 (0%) | 6 (66.67%) | 0 (0%) |

| Northeast | Nakhon Ratchasima | 2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Udon Thani | 2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2009 | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2008 | West | Nakhon Pathom | 9 | 0 (0%) | 7 (77.78%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 241 | 15 (6.22%) | 144 (59.75%) | 0 (0%) | ||

Of the 15 PDCoV-positive samples, one from 2013, one from 2014, and two from 2015 were further characterized by full-length genome sequencing. The full-length genome sequences of the four Thai PDCoV isolates, one isolate detected in 2013 (P1_13_ST1_0213), one isolate detected in 2014 (P2_14_ST2_0214) and two isolates detected in 2015 (P23_15_TT_1115 and P24_15_NT1_1215), are 25,400-25,404 nucleotides (nt) in length, with a genome organization similar to that of all previously reported PDCoV genomes: 5’UTR-ORF1a/1b-S-E-M-Nsp6-N-Nsp7-3’UTR [7, 14]. The ORF1a/1b, S, E, M, Nsp6-N-Nsp7 genes are 18,786, 3,477, 249, 651, 282, 1,026 and 600 nucleotides in lengths, respectively (Table 2). Substitutions and deletions/insertions at the amino acid level occurred in several sequence regions, especially the ORF1a/1b and S genes, of the four Thai PDCoV strains when compared to variants from the United States and China (Table 2). Interestingly, all four Thai PDCoV strains had amino acid deletions at 401LK402 and 758PVG760.

Table 2.

Gene lengths in four Thai PDCoV isolates and positions of amino acid deletions/insertions and substitutions in Thai PDCoV isolates compared to the other two PDCoV groups

| Thai isolates | Gene | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1a/1b | S | E | M | N | |||

| ST1_0213 | Length | Nucleotides | 18,786 | 3,477 | 249 | 651 | 1,026 |

| Amino acids | 6,262 | 1,159 | 83 | 217 | 342 | ||

| China group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | 571V | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | 51N | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 91 | 35δ | - | 1 | 5 | ||

| US group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | 571V | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 96 | 33δ | - | 1 | 5 | ||

| ST2_0214 | Length | Nucleotides | 18,786 | 3,477 | 249 | 651 | 1,026 |

| Amino acids | 6,262 | 1,159 | 83 | 217 | 342 | ||

| China group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | 571V | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | 51N | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 91 | 37δ | - | 1 | 5 | ||

| US group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | 571V | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 96 | 35δ | - | 1 | 5 | ||

| TT_1215 | Length | Nucleotides | 18,786 | 3,477 | 249 | 651 | 1,026 |

| Amino acids | 6,262 | 1,159 | 83 | 217 | 342 | ||

| China group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | - | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 90 | 23δ | - | 1 | 4 | ||

| US group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | - | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 95 | 23δ | - | 1 | 4 | ||

| NT1_1215 | Length | Nucleotides | 18,786 | 3,479 | 249 | 651 | 1,026 |

| Amino acids | 6,262 | 1,160 | 83 | 217 | 342 | ||

| China group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | - | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | 51N | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 139 | 27δ | - | 1 | 3 | ||

| US group | Deletions* | 401LK402 and 758PVG760 | - | - | - | - | |

| Insertions* | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Number of substitutions | 144 | 27δ | - | 1 | 3 | ||

* The numbers indicate the position in each gene

δAmino acid substitutions at different positions

The pairwise nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity values of the full-length genome sequences of the four Thai PDCoV isolates are shown in Table 3. These sequences were 98.8-99.1% identical at the nucleotide and 97.4-97.9% identical at the amino acid level and were more closely related to each other and to variants from China and the United States than to Thai strains isolated in 2015, suggesting that the Thai PDCoV population is continuously changing.

Table 3.

Pairwise nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity values for the full-length genome sequence of the Thai PDCoV isolates from 2013, 2014 and 2015 compared to PDCoV variants from China and the USA

| Year | China PDCoV variants | US PDCoV variants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide (%) | Amino acid (%) | Nucleotide (%) | Amino acid (%) | |

| 2013 and 2014 | 97.2-97.8 | 93.8-95.2 | 97.3-97.4 | 94.2-94.4 |

| 2015 | 96.9-97.8 | 93.2-95.0 | 97.0-97.3 | 93.5-94.2 |

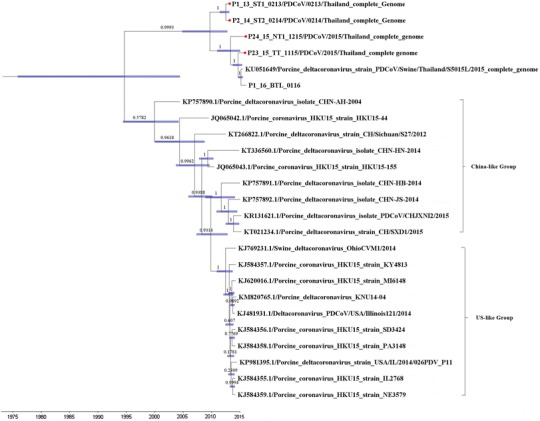

Phylogenetic analysis based on the full-length genome sequence demonstrated that PDCoV isolates are divided into two groups, the Chinese- and US-like-groups, as was reported previously [1]. All four Thai PDCoV isolates were grouped in a novel cluster separate from variants from the United States and China but were more closely related to the Chinese isolates than to the US PDCoV isolates (Fig. 1). The currently circulating isolates of PDCoV share a common ancestor that was present around 1994, with 95% HPD values covering 30 years from 1975 to 2004 (Fig. 1). Since then, Thai and US/China PDCoV clades diverged from the common ancestor and evolved independently. The emergence of the Thai lineage was estimated to have occurred between 2004 and 2012, while the US/China lineage evolved earlier, between 1994 and 2003. The clustering of the PDCoV isolates in the Thai PDCoV clade is well supported, with a posterior probability of 0.9993. Thai PDCoV sequences isolated in 2013 and 2014 grouped separately from Thai PDCoV sequences isolated in 2015. Moreover, all four Thai PDCoV isolates were descended from a common ancestor between 2004 and 2014 (Fig. 1). The analysis of amino acid changes also suggests that they are from a different lineage.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) based on nucleotide sequences of the full-length genome performed using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (BMCMC) method. The red dots represent Thai PDCoV isolates

In conclusion, we retrospectively investigated the presence of PDCoV in Thailand and found that PDCoV has been present in Thailand since at least February 2013 and that it is present in mixed infections with PEDV. Interestingly, the PDCoV variants in Thailand are different from variants in other countries and belong to a novel group of PDCoV strains. Evolutionary analysis suggested that the Thai PDCoV isolates likely diverged from a different ancestor from that of the Chinese and US PDCoV isolates, and the separation occurred after 1994. This study provides interesting results associated with the emergence and the evolution of PDCoV. Further investigation, including more retrospective studies of available samples, will provide a better understanding of this pathogen.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (Grant Number 5080001) and the Agricultural Research Development Agency (public organization). We gratefully acknowledge the graduate scholarship program of Chulalongkorn University and the funding provided by the Special Task Force for Activating Research (STAR), Swine Viral Evolution and Vaccine Research (SVEVR), Chulalongkorn University.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study was funded by the Thailand Research Fund (Grant Number MRG5080323) and the National Research Council of Thailand (Grant Number 5080001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

References

- 1.Dong N, Fang L, Zeng S, Sun Q, Chen H, Xiao S. Porcine deltacoronavirus in Mainland China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2254–2255. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.150283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung K, Hu H, Eyerly B, Lu Z, Chepngeno J, Saif LJ. Pathogenicity of 2 porcine deltacoronavirus strains in gnotobiotic pigs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:650–654. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim O, Choi C, Kim B, Chae C. Detection and differentiation of porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus and transmissible gastroenteritis virus in clinical samples by multiplex RT-PCR. Vet Rec. 2000;146:637–640. doi: 10.1136/vr.146.22.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Lee C (2014) Complete genome characterization of Korean porcine deltacoronavirus strain KOR/KNU14-04/2014. Genome Announc 2:e01191-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Li G, Chen Q, Harmon KM, Yoon KJ, Schwartz KJ, Hoogland MJ, Gauger PC, Main RG, Zhang J (2014) Full-length genome sequence of porcine deltacoronavirus strain USA/IA/2014/8734. Genome Announc 2:e00278-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lorsirigool A, Saeng-Chuto K, Madapong A, Temeeyasen G, Tripipat T, Kaewprommal P, Tantituvanont A, Piriyapongsa J, Nilubol D (2016) The genetic diversity and complete genome analysis of two novel porcine deltacoronavirus isolates in Thailand in 2015. Virus Genes 53:240–248 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lorsirigool A, Saeng-Chuto K, Temeeyasen G, Madapong A, Tripipat T, Wegner M, Tuntituvanont A, Intrakamhaeng M, Nilubol D. The first detection and full-length genome sequence of porcine deltacoronavirus isolated in Lao PDR. Arch Virol. 2016;161:2909–2911. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2983-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saeng-Chuto K, Lorsirigool A, Temeeyasen G, Vui DT, Stott CJ, Madapong A, Tripipat T, Wegner M, Intrakamhaeng M, Chongcharoen W, Tantituvanont A, Kaewprommal P, Piriyapongsa J, Nilubol D. Different lineage of porcine deltacoronavirus in Thailand, Vietnam and Lao PDR in 2015. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64:3–10. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha A, Gauger P, Zhang J, Yoon KJ, Harmon K. PCR-based retrospective evaluation of diagnostic samples for emergence of porcine deltacoronavirus in US swine. Vet Microbiol. 2015;179:296–298. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temeeyasen G, Srijangwad A, Tripipat T, Tipsombatboon P, Piriyapongsa J, Phoolcharoen W, Chuanasa T, Tantituvanont A, Nilubol D. Genetic diversity of ORF3 and spike genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Thailand. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo PC, Lau SK, Lam CS, Lau CC, Tsang AK, Lau JH, Bai R, Teng JL, Tsang CC, Wang M, Zheng BJ, Chan KH, Yuen KY. Discovery of seven novel Mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J Virol. 2012;86:3995–4008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.