Abstract

Bordetella pertussis or whooping cough is a vaccine-preventable disease that still remains a serious infection in neonates and young infants. We describe two young infants, monozygotic twins, with a severe B. pertussis pneumonia of whom one needed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Diagnostic work-up of unexplained hematuria and proteinuria during the illness revealed low serum complement component 3 (C3) levels. During follow-up, C3 levels remained low (400–600 mg/L). Extensive analysis of the persistent low C3 levels revealed an unknown heterozygous mutation in the C3 gene in both siblings and their mother. This C3 mutation in combination with the specific virulence mechanisms of B. pertussis probably contributed to the severe disease course in these cases. Conclusion: We propose that genetically caused complement disorders should be considered when confronted with severe cases of B. pertussis infection.

Keywords: Bordetella pertussis, Infant, Complement, Complement inhibitors, Complement C3

Introduction

Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is an infectious respiratory disease caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Bordetella pertussis. Annually, there are 20–40 million cases of pertussis worldwide, with as many as 400,000 pertussis-related deaths each year, occurring mostly in developing countries and in young infants [4].

The more severe disease manifestations seen in neonates and young infants before or in the absence of vaccination is partially due to diminished maternal derived protective antibodies. Although maternal antibodies against B. pertussis are transported across the placenta [6], it has been shown that women in childbearing age nowadays have lower antibodies against childhood disease because of the lack of natural boosters due to vaccination. As a result, there has been a renewed interest in maternal vaccination to prevent neonatal pertussis infections [8].

In preterm neonates, in general, low antibody concentrations are found compared to term neonates. Heininger et al. recently demonstrated that preterm infants have lower antibody levels against B. pertussis, which increase with gestational age [6]. This implies a greater risk of pertussis infection when born prematurely.

In this report, we describe two young infants, monozygotic twins, who were born prematurely, with severe B. pertussis pneumonia in which a complement disorder was detected resulting in low complement component 3 (C3) levels. The relation between C3 deficiency and disease severity caused by B. pertussis is discussed.

Case report

The female monochorionic diamniotic twins were born at a gestational age of 31 weeks and 6 days after preterm premature rupture of membranes. Celestone was given 24 h before birth. Both twins had a good start (Apgar score 7/9/9), with twin A weighing 1,550 g (P50) and twin B weighing 1,720 g (P50-80). Postnatally, they developed an infant respiratory distress syndrome grades I and II, needing continuous positive airway pressure, but otherwise the neonatal period was unremarkable. Four weeks after birth, they were discharged from the hospital in good clinical condition.

At the age of 7.5 weeks (adjusted for preterm birth, 2.5 weeks), twin A presented at the local hospital with an obstinate and increasing cough, feeding difficulties, and decreasing urine production, without fever. Physical examination of the chest revealed crackling sounds over both lungs. Laboratory findings demonstrated a leukocyte count of 16.4 × 109/L (normal value for age, 5–17 × 109/L) with 73 % lymphocytes and a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 1 mg/L (normal value for age, <10 mg/L). The chest X-ray showed increased peribronchiolar consolidation and some consolidation of the upper lobe of the left lung. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza types 2–4, coronavirus, adenovirus, bocavirus, rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, and influenzas A and B was negative. A bacterial pneumonia was suspected, for which she was treated with amoxicillin orally.

Despite this therapy, coughing increased over 2 days and recurrent episodes of severe paroxysmal cough were followed by apnea and bradycardia. Although continuous oxygen flow and caffeine were given, the periods of apnea became more frequent and severe. Endotracheal intubation with ventilatory support was indicated and she was transferred to the nearest pediatric intensive care unit.

On admission, blood test results showed a leukocyte count of 80 × 109/L and a lymphocyte count of 75 %, with a CRP of 175 mg/L. The chest X-ray showed bilateral diffuse infiltrates and consolidation of both lungs. Antibiotics were switched to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid which was administered intravenously. In the mean time, the PCR for B. pertussis was found to be positive in the sputum of her twin sister (twin B) and turned out to be positive in her sputum as well. Therefore, the antibiotic regime was changed from amoxicillin–clavulanic acid to azithromycin.

Periods of low oxygen saturation became more frequent with episodes of bronchospasms that initially responded well to bronchodilators. Ultrasonography of the heart revealed pulmonary hypertension with mean arterial pressures up to 60 mmHg with signs of tricuspid insufficiency. High-frequency oscillation with nitrogen monoxide (NO) ventilation was needed and the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was considered for which she was transferred to our pediatric intensive care unit.

After initial improvement on NO ventilation with magnesium sulfate administered intravenously, her pulmonary condition worsened and she developed a more severe pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, ECMO treatment was started. This treatment was complicated by severe hypertension, pleura exudate, and fluid overload, which was treated with continuous veno-venous hemofiltration. Another complication, of which the origin was not exactly clear, was an ischemic stroke of the brain in the region of the right posterior cerebral artery and a watershed cerebral infarct of the right medial cerebral artery. This led to a hemiparesis and a hemianopsia on the left side. Eventually, 16 days of ECMO therapy was needed before her pulmonary condition improved.

During the ECMO treatment, twin A developed hematuria (25–50 RBCs per high-power field) and proteinuria (117 mg/mmol protein/creatinine ratio; normal value for age, <60 mg/mmol) with red cell casts, suggesting glomerulonephritis. However, serum creatinine levels (17–20 μmol/L; normal value for age, 10–30 μmol/L) and blood pressure (63/32 mmHg, p50 for age) were normal. Extensive blood and urine analysis revealed low serum complement C3 levels without other abnormalities (Table 1). The girl eventually recovered and was discharged after 2 months of intensive treatment. At the age of 18 months, she has a delayed psychomotor development and epileptic seizures, which are controlled by antiepileptic medication.

Table 1.

Serum complement C3 and C4 levels and C3 breakdown product C3d over time

| Start of hematuria | 1 month after hematuria | 4 months after hematuriaa | 7 months after hematuriab | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3 (mg/L) | C4 (mg/L) | C3 (mg/L) | C4 (mg/L) | C3 (mg/L) | C4 (mg/L) | C3 (mg/L) | C4 (mg/L) | C3d (%) | |

| Twin Ac | 619 | 220 | 515 | 186 | 441 | 118 | 556 | 170 | 1.22 |

| Twin Bc | 632 | 197 | 1.47 | ||||||

| Motherc | 490 | 141 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Father | 1,200 | 232 | 1.23 | ||||||

| Normal values | 700–1,500 | 100–400 | <3.30 | ||||||

aThree months after discharge from hospital

bSix months after discharge from hospital

cThe C3 mutation was present in the marked individuals

Her twin sister, twin B, developed the same signs and symptoms only 1 day later. She was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit and intubated because of respiratory failure. Ventilatory support with caffeine was needed for 2 weeks. She was treated with clarithromycin. She did not develop any signs of glomerulonephritis, but additional analysis of complement factors revealed low serum C3 levels as well. Twin B was discharged after 6 weeks of admission. Although severe, she displayed a less dramatic disease course compared to her twin sister. This could be explained by the fact that B. pertussis PCR on sputum was positive in an earlier stage and timely treatment with macrolides was commenced. During follow-up, the girl shows a normal psychomotor development at the age of 18 months.

Analysis of complement factors

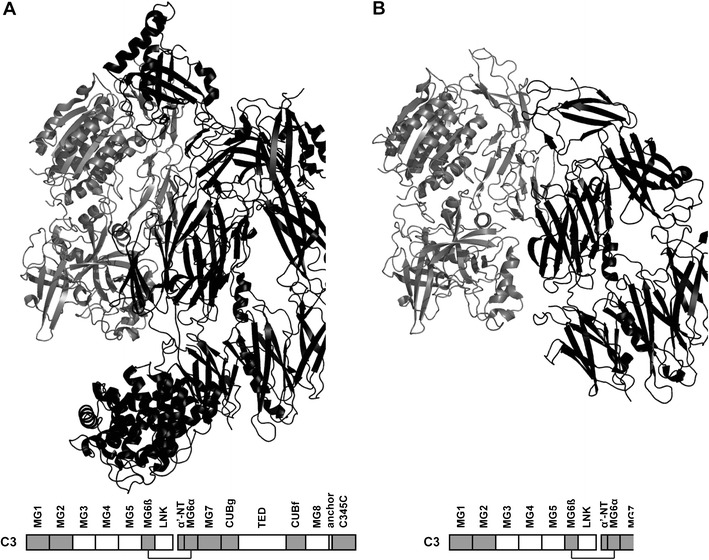

During the follow-up of twin A, serum analysis demonstrated persistent low C3 levels (400–600 mg/L) with normal C4 levels (100–200 mg/L) as shown in Table 1, suggesting alternative complement pathway involvement. A genetic cause was suspected and parents gave permission to study the genes encoding the most important alternative complement pathway proteins (factor H, factor I, membrane cofactor protein, complement factor B [CFB], and C3). In both siblings, a previously unknown deletion of one nucleotide was identified in exon 21 of the gene encoding C3 (c.2696delT, p.Val899AlafsX5). This mutation causes a frameshift, leading to a preliminary stop (five amino acids after the deletion) in the MG7 domain of the protein. The mutant protein is almost 46 % shorter than wild-type C3, resulting in the loss of important binding sites for CFB and the loss of the thioester bond important for the function of the protein (Fig. 1) [5]. Genomic DNA analysis in both parents showed a maternal inheritance; the mother of the twins is generally healthy, but recalls being frequently sick and suffering from upper respiratory tract infections as a child.

Fig. 1.

Structural implications for the p.Val899AlafsX5 mutation. The 3D structure of the active C3 cleavage product C3b (black) in complex with CFB (gray) and the domain structure of C3 are depicted for both the wild-type (a) and the mutant protein (b). In gray, the C3 domains involved in CFB binding are indicated [5]. The images were generated using PyMOL with the Protein Data Bank file 2XWB

The mutation probably leads to absent secretion of mutant C3 due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, which is indicated by serum C3 levels of about half of the normal. Consequently, one may expect that this mutation leads to an impaired complement activation system.

Discussion

A congenital C3 deficiency was detected in monozygotic female twins during severe B. pertussis pneumonia in infancy. Although it is well known that neonates and young infants are at increased risk for developing severe whooping cough due to a so-called immature immune system [6, 8], the significance of abnormalities in the complement pathway related to disease severity, as described here, needs further investigation [10].

The complement cascade consists of the classical, lectin, and alternative pathway, all converging at complement C3. Further activation of the complement cascade leads to the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) by which particular microorganisms can be eliminated by the immune system [2]. This whole process is regulated by different complement inhibitors and promoters. B. pertussis is a Gram-negative encapsulated bacterial strain of which the microcapsule is not protective against complement attack [9], but B. pertussis is able to bind the classical pathway inhibitor C4b-binding protein [3], the C1 esterase inhibitor [7], and the alternative pathway inhibitor factor H [1] to evade the complement system, in that way protecting itself and making it possible to colonize a host.

Finally, the remarkable persistent low C3 levels in these patients led us to examine the major alternative complement pathway proteins on genomic level. The newly found mutation possibly causes lack of C3 secretion and can therefore be the reason for the persistent decreased serum C3 levels. Consequently, this causes less formation of MAC on bacteria and therefore leads to an impaired elimination of B. pertussis.

In conclusion, these severe cases of infantile B. pertussis pneumonia in premature born twins might well have been caused by a mutation in the C3 gene, resulting in deficient C3 levels in serum, in addition to an immature immune system. Accordingly, one should consider to screen for abnormal complement protein levels when confronted with such a severe infection to B. pertussis or other pathogens that can evade the complement system by using similar mechanisms, as an underlying genetically caused complement disorder might be present.

Acknowledgments

D.W. is supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation (C09.2313).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- C3

Complement component 3

- CFB

Complement factor B

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- NO ventilation

Nitrogen monoxide ventilation

- MAC

Membrane attack complex

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Amdahl H, Jarva H, Haanpera M, Mertsola J, He Q, Jokiranta TS, Meri S. Interactions between Bordetella pertussis and the complement inhibitor factor. H. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes MG, Weiss AA. Activation of the complement cascade by Bordetella pertussis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;220:271–275. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berggard K, Johnsson E, Mooi FR, Lindahl G. Bordetella pertussis binds the human complement regulator C4BP: role of filamentous hemagglutinin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3638–3643. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3638-3643.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowcroft NS, Pebody RG. Recent developments in pertussis. Lancet. 2006;367:1926–1936. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68848-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forneris F, Ricklin D, Wu J, Tzekou A, Wallace RS, Lambris JD, Gros P. Structures of C3b in complex with factors B and D give insight into complement convertase formation. Science. 2010;330:1816–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.1195821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heininger U, Riffelmann M, Leineweber B, Wirsing von Koenig CH. Maternally derived antibodies against Bordetella pertussis antigens pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin in preterm and full term newborns. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:443–445. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318193ead7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marr N, Luu RA, Fernandez RC. Bordetella pertussis binds human C1 esterase inhibitor during the virulent phase, to evade complement-mediated killing. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:585–588. doi: 10.1086/510913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooi FR, de Greeff SC. The case for maternal vaccination against pertussis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:614–624. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neo Y, Li R, Howe J, Hoo R, Pant A, Ho S, Alonso S. Evidence for an intact polysaccharide capsule in Bordetella pertussis. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ram S, Lewis LA, Rice PA. Infections of people with complement deficiencies and patients who have undergone splenectomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:740–780. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00048-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]