Abstract

In this study, RNA corresponding to bovine enterovirus (BEV) was detected in 24.6 % of faecal samples (17/69) from diarrheic and healthy cattle in six different areas in China by an RT-PCR screening method. Furthermore, two cytopathic agents, designated as BHM26 and BJ50, were isolated from the bovine diarrheic fecal samples. During passage in MA104 cells, ultrathin sections of virus-infected monolayers were examined using a transmission electron microscope, and a large number of symmetrical virus crystals were seen in the cytoplasm, with monomorphic small viral particles of 27-30 nm in diameter. The full-length RNA genomes were 7433 and 7416 nucleotides long, respectively, with a genome organization analogous to that of picornaviruses. Phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 and VP3 capsid protein coding sequences suggested that the viruses BHM26 and BJ50 belong to genotype 2 of the BEV cluster B (BEV-B). In addition, sequence comparisons of the 5′ and 3′ UTRs and P1, P2 and P3 subgenomic regions of the two isolates suggested that there were intergenotypic recombination events occurring during evolution of the BHM26 and BJ50 isolates.

Keywords: MA104 Cell, Vaccine Vector, Healthy Cattle, Enteric Tract, Bovine Enterovirus

Introduction

Bovine enteroviruses (BEVs), which are members of the family Picornaviridae, genus Enterovirus, form two phylogenetic clusters (designated BEV-A and -B), with two and three genotypes, respectively [15]. BEV virions consist of a naked capsid that surrounds a core of positive-sense, single-stranded RNA. Hydrated native particles are 27-30 nm in diameter in electron micrographs, which reveal the virion to be a smooth sphere. The BEV genome is approximately 7.4 kb long and has a typical picornavirus genome organization, including VPg following the 5′ UTR, structural (VP4, VP2, VP3 and VP1) regions, nonstructural (2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C and 3D) regions, 3′ UTR and a poly (A) tail [2].

BEVs were first isolated in the late 1950s [3, 6]. They were isolated from (i) faeces of cattle with symptoms of pneumonia, respiratory disease, enteritis, dysentery and fertility disorders, (ii) fetal fluids from an aborted calf, (iii) the faeces of apparently healthy animals, and (iv) sewage, treated effluents, and materials from a farm environment. Difficulties in reproducing clinical symptoms following experimental infection of animals led to the conclusion that BEVs were of only minor veterinary medical importance. However, they have been shown to be widely detectable in a farm environment and have thus been proposed as markers for fecal contamination from cattle [7]. It is generally assumed that BEVs are avirulent, and if so, it is possible that they would make useful vectors for delivery of small molecules to the gut. Additionally, BEVs have been shown to have oncolytic properties and may be useful as therapeutic agents [12, 13]. For these various reasons, we were interested in learning about the epidemiology and molecular evolution of BEVs from China.

In this study, a preliminary epidemiological study was performed, the results of which suggested that BEVs are present in certain cattle in China. Also, the present report described the first isolation, by means of MA104 cell cultures, of two isolates of BEV (designated BHM26 and BJ50) obtained from rectal swabs from diarrheic cattle of dairy herds in China. These viruses were characterized molecularly through sequence analysis of complete genomes, and the BHM26 and BJ50 isolates were therefore classified into genotype 2 of the BEV-B cluster. The complete genome sequences of two Chinese BEV isolates not only enhance the database of sequences of members of the family Picornaviridae, providing data of use to picornavirus virologists, but they also can be used further for construction of a BEV infectious clone and development of BEV-vectored vaccines based on epitopes.

Materials and methods

Bovine fecal samples and virus isolation and propagation

A total of 69 fecal samples were collected from cattle at six farms in China from October 2007 to July 2010. Out of a total of 69 fecal samples, 59 were from animals with diarrhea and 11 were from non-diarrheic animals. The samples were collected from Inner Mongolia (n = 11), Heilongjiang (n = 12), Anhui (non-diarrheic samples, n = 11), Liaoning (n = 12), Xinjiang (n = 12) and Shanghai (n = 11), which are the main production areas of cattle in China. Stool specimens were stored at -70 °C until the testing was performed.

The samples were diluted 1:10 in 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), clarified by low-speed centrifugation (3000 × g for 10 min), and kept at -70 °C until they were used to isolate viruses. Monolayers of MA104 cells grown for 1 or 2 days were used for virus isolation. The growth medium was Dulbecco′s minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 8 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U of penicillin per ml and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml). The centrifuged fecal samples were filtered through 0.22-μm filters (Millex, Millipore). Subsequently, 1 ml of filtrate was inoculated onto a MA104 cell monolayer that had been grown in flasks and washed three times with PBS. After adsorption for 60 min at 37 °C, 4 ml of fresh medium (without FBS) was added, the cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. When cytopathic effect (CPE) was not observed one week after inoculation, or the cells showed 50 to 80 % CPE, the cultures were frozen and thawed three times for harvest of cell lysates. Subsequent passages were carried out in the same manner by using 0.1 ml of cell suspension from the previous passage as the inoculum.

RT-PCR and sequencing

Total RNA from fecal samples and virus-infected MA104 cells was extracted by using TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer′s instructions. Extracted viral RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis using PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase (TaKaRa). Oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) used in this study were designed according to the consensus sequences of the 12 fully sequenced BEV RNA genomes available from the GenBank database. RT-PCR was carried out with an initial reverse transcription step of 60 min at 42 °C, followed by PCR for activation at 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 0.5 min, annealing for 0.5 min at 51 °C to 55 °C depending on the Tm values of the different primers, and extension at 72 °C for 1.5 min using a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA). The final extension step was done at 72 °C for 10 min. The 5′ ends of the virus genomes were amplified using a 5′-Full RACE Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer′s instructions. Sequences at the 3′ end of the virus genomes were determined using RT-PCR, with first-strand cDNA synthesis carried out using an oligo (dT) primer, thus taking advantage of the poly (A) tail in BEV RNA genomes as a priming site. All of the PCR products were detected by electrophoresis in 1 % agarose gels and were purified using a DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Watson Biotechnologies, Inc., Shanghai, China). They were then sequenced directly in both directions by a commercial service (Invitrogen, China).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification of the BHM26 and BJ50 genomes

| Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| 1U25a | TTTAAAACAGCCTGGGGGTTGTACC |

| 1052L21a | GCGCAACGCGATCACTATATC |

| 921U21a | TGAGAACGCCGCATCCAACAG |

| 1912L21a | GATCTCAACAAGCGACTCAAC |

| HC-PRIMER1b | ACGGGAAAGGTCGTAGTTG |

| HC-PRIMER3b | GGGCAATCGTGTCAGAGC |

| 3818L21b | ACCGACGAGATTTCCAACTAC |

| 4896L21b | AAACGAGGGGCATACACTTCT |

| 4603U24b | GAACCCAGATGGGAAGGATATGAG |

| 5504L24b | AACCTCCCCATGAGCCATGGCGTG |

| 5444U20b | TGCAGACCAAGGTAGGTGAG |

| 6612L20b | CAAAGAGCTCCCCATCCATC |

| 1804U21c | TTTCTCACCACGGATGACTTC |

| 2872L21c | GTGTTCATGCGATACCTTGTC |

| 2625U19c | CGCAAGTGATGAAAGCCTC |

| 3647L19c | CGAAGTATTCCGCCGCAAT |

| 3371U19c | TTCTGAATCGGCACTTAGC |

| 4345L19c | GAGCTTCTGCCGCATACAG |

| 4098U19c | AGCTGTCAACGCCTTCAAA |

| 5176L19c | CTTGAACAATCCAGCCCTT |

| 5026U19c | ATCGGGAATGTGATTGAGG |

| 6057L19c | CTTGTGAAGAACGGCTGGT |

| 5844U21c | CATTTCCATGGGCAAGATTAT |

| 6585L21c | GGTATCTTGCTCCAAAATGTC |

| 6424U24a | ATCCAAAGAGAAAGTGAAGAAGGG |

| 7450L24d a | CCGGGGGCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT |

| 534L24* a | GAGGTTGGGATTAGCAGCATTCAC |

| 606L24* a | CCGAAAGTAGTCTGTTCCGCCTCC |

aThe primers for PCR amplification of the BHM26 and BJ50 genomes

bThe primers for PCR amplification of the BJ50 genome

cThe primers for PCR amplification of the isolate BHM26 genome

dNon-BEV-specific sequences are shown in boldface type; the G and C nucleotides were added in order to balance the G+C content of the primer so that PCR can be easily performed

* These primers were used as the lower primer of the 5′ RACE

Sequence analysis

The complete nucleotide sequences of the isolates were assembled from the sequence fragments using the SeqMan module of the DNASTAR software package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI). Amino acid sequences were deduced from the nucleotide sequences using the EditSeq module. Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA, version 4.0) software, and bootstrap resampling analysis of 1000 replicates was performed.

Results

Detection and isolation of BEV in bovine stool samples

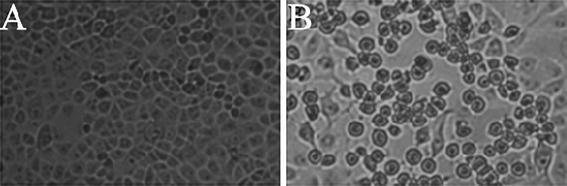

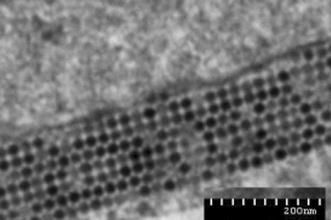

A total of 69 bovine diarrheic and healthy faecal specimens from six different areas were examined by RT-PCR using the primer pair 6424U24 and 7450L24, which cover the highly conserved partial 3D gene and 3′UTR of BEVs. The results showed that virus-specific RNA could be detected directly in faecal material in 17 of 69 samples (24.6 %). The prevalence rate of BEV in the six cattle farms located in Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Liaoning, Xinjiang, and Shanghai was 45.4 % (5/11), 25 % (3/12), 27.2 % (3/11), 16.7 % (2/12), 25 % (3/12) and 9 % (1/11), respectively, indicating that BEVs are present in certain domestic cattle of China. All of the BEV-specific-RNA-positive faecal samples from Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang were inoculated onto MA104 cells for isolation of BEV. After the centrifuged fecal samples were inoculated onto cell monolayers, CPE was observed in the second-passage culture on the third day in culture plates inoculated with stool specimens 26 (from Inner Mongolia) and 99050 (from Xinjiang). The cultivated virus derived from sample 26 was designated BHM26, and that from the sample 99050 was designated BJ50. Distinctly recognizable CPE was observed until the third passage at 12 to 24 h after infection. The CPE produced by the two isolates consisted of obscure cell borders, cell rounding, piling up of cells, and detachment of cells from the surface of plates (Fig. 1). Ultrathin sections of the infected monolayers were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a transmission electron microscope. A large number of symmetrical virus crystals were seen in the cytoplasm, and the monomorphic small viral particles with a diameter of 27-30 nm were consistent with viruses of the family Picornaviridae (Fig. 2). The presence of BEVs in cell cultures was further detected by RT-PCR with the primer set 6424U24 and 7450L24, indicating that the two isolates were BEV positive. PCR products were sequenced directly in both directions, and sequence alignments were conducted by using MEGA version 4.0. The results showed that the 3D/3′ UTR (1026 nt) of BHM26 and BJ50 shared 86 % and 88 % nucleotide sequence identity, respectively, to that of BEV strain Jena38/02 (GenBank accession number: DQ092789), indicating that the two isolates are bovine enterovirus.

Fig. 1.

Uninoculated monolayer of MA104 cells (A), CPE of the MA104 cells at 12 h after infection (B)

Fig. 2.

Ultrathin sections of cell monolayers infected with isolate BHM26 were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined using a transmission electron microscope. A large number of symmetrical virus crystals were seen in the cytoplasm, and the monomorphic small viral particles with a diameter of 27-30 nm were consistent with viruses of family Picornaviridae. Bar = 200 nm

Nucleotide sequences of the complete BHM26 and BJ50 genomes

Several overlapping PCR amplifications spanning the entire genomes of the BHM26 and BJ50 isolates were obtained, and their complete nucleotide sequences were determined. The BHM26 and BJ50 genomes consist of 7,433 bp and 7,416 bp, including 42 and 21 A bases, respectively, in the poly (A) tail. The complete genomes of the two isolates have a typical picornavirus genome organization, including a 5′ UTR, a large single ORF, a 3′ UTR and a poly(A) tail. The ORF of BHM26 is located between nucleotides 823 and 7,326 and encodes a potential polyprotein of 2,167 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular mass of about 240.9 kDa and an isoelectric point (pI) of 6.49. The ORF of BJ50, beginning at ATG (821-823) and terminating at TAA (7,322-7,324), encodes a putative 240.2-kDa polyprotein of 2,167 amino acid residues with an isoelectric point (pI) of 6.56. The complete genome sequences of isolates BHM26 and BJ50 have been submitted to GenBank under accession nos. HQ917060 and HQ917061, respectively.

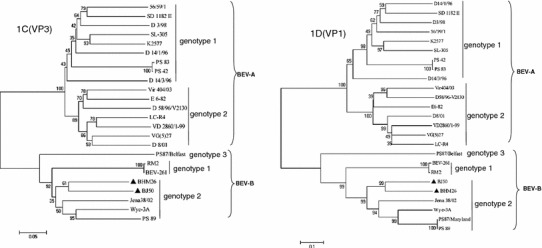

Phylogenetic analysis

Low nucleotide sequence identity of the genes encoding the capsid proteins 1C and 1D is the main criterion for the identification of genotypes of BEV [15]. Thus, phylogenetic analysis of the 1C and 1D encoding regions of the two isolates and other representative BEV strains was performed to determine the phylogenetic characteristics of the two BEV isolates. It was found that both BHM26 and BJ50 were classified into genotype 2 of the BEV-B cluster and were most closely related to BEV strain Jena38/02 (Fig. 3), an isolate from Germany (GenBank accession number: DQ092788). Furthermore, similar results were obtained when the 1C and 1D encoding regions were used to analyze phylogenetic relatedness among the BEV strains, although the branch orders were somewhat different (Fig. 3), showing that the 1C and 1D coding regions can be used simultaneously to determine the genotypes of the BEV strains.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of isolates BHM26 and BJ50 based on the nucleotide sequences of their 1C and 1D genes. The trees were generated by the neighbor-joining method and bootstrap testing. The sequences and their accession numbers in the GenBank database are as follows: PS87/Belfast (DQ092794), Jena38/02(DQ092788), Wye-3A(AY508697), PS87/Maryland(AY508696), PS89(DQ092795), RM2(X79369), BEV-261(DQ092770), D3/98(DQ092790), 56/59/1(DQ092778), SD 1182II(DQ092784), D14/1/96(DQ092780), SL-305(AF123433), K2577(AF123432), PS83(DQ092793), PS42(DQ092792), D14/3/96(DQ092786), Vir404/03(DQ092771), LC-R4(DQ092769), VG(5)27(D00214), VD2860/1-99(DQ092774), D8/01(DQ092782), D58/96-V2130 (DQ092772), E6-82(DQ092776), and the BHM26(HQ917060) and BJ50(HQ917061) sequenced here

Sequence comparisons with other BEV strains

The complete genomes of BHM26 and BJ50 were divided into 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR and P1, P2 and P3 subgenomic regions for sequence comparisons with those of the referenced BEV strains. For these subgenomic regions, the two sequenced isolates shared 88.6 % (5′ UTR), 94.1 % (3′ UTR), 80.6 % (P1), 80.9 % (P2) and 82.2 % (P3) nucleotide sequence identity (Table 2), and they shared 86.4–90.2 % (5′ UTR), 94.1-97.3 % (3′ UTR), 69.1-75.9 % (P1), 74.9-80.8 % (P2) and 80.3-84.9 % (P3) nucleotide sequence identity with the other strains of the BEV-B cluster (Table 2) while sharing only 75.6-78.3 % (5′ UTR), 80-84.6 % (3′ UTR), 62-63.2 % (P1), 66.6-69.5 % (P2) and 68.4-70.6 % (P3) nucleotide sequence identity with strains of the BEV-A cluster (data not shown). For the BHM26 isolate, comparison analysis using the 3′ UTR showed the closest relationship between PS89 (95.9 %) and PS87/Belfast (95.9 %) (Table 2); however, in the 5′ UTR, P1, P2 and P3 region comparisons, BHM26 was most closely related to the BJ50 isolate (Table 2). Meanwhile, comparison of the 3′ UTR showed that BJ50 shared the highest level of sequence identity with PS89 (97.3 %) and Wye-3A (97.3 %) (Table 2), whereas in the 5′ UTR, P1, P2, and P3 comparisons, BJ50 was most closely related to BEV-261, BHM26 and PS87/Belfast, respectively (Table 2). These incongruent phylogenies of the subgenomic regions suggested that the BHM26 and BJ50 are recombinant BEV isolates.

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequence identities between the BHM26 and BJ50 and the referenced BEV-B cluster strains by comparisons of subgenomic regions

| Region | Strain | BEV-B cluster | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BJ50 | BEV-261 | PS87/Belfast | PS89 | PS87/Maryland | Wye-3A | ||

| 5′ UTR | BHM26 | 88.6 | 87.6 | 87.7 | 86.4 | 86.6 | 87.1 |

| BJ50 | – | 90.2 | 89 | 88 | 88.1 | 89.6 | |

| 3′ UTR | BHM26 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 94.1 | 94.1 |

| BJ50 | – | 95.9 | 95.9 | 97.3 | 95.9 | 97.3 | |

| P1 | BHM26 | 80.6 | 73.9 | 69.1 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 75.3 |

| BJ50 | – | 72.4 | 70.2 | 75.9 | 75.9 | 75.4 | |

| P2 | BHM26 | 80.9 | 74.9 | 77.7 | 78.8 | 78.7 | 78.8 |

| BJ50 | – | 78.1 | 78.3 | 80.8 | 80.7 | 80.4 | |

| P3 | BHM26 | 82.2 | 82.1 | 80.4 | 80.4 | 80.3 | 81.3 |

| BJ50 | – | 84.5 | 84.9 | 84.0 | 83.8 | 84.6 | |

Bold values indicate the highest level of nucleotide sequence identities between the BHM26 and BJ50 isolates and the representative BEV strains

Discussion

In the present study, we first conducted a preliminary epidemiological survey for detecting BEVs from diarrheic and healthy cattle in of China. A total of 69 bovine fecal samples collected from the six different areas of China were tested by RT-PCR, and 17 samples (24.6 %) in the six areas were positive for BEV, indicating that BEVs are widespread in dairy farms in China. Subsequently, two BEV isolates (designated BHM26 and BJ50) were isolated from bovine fecal specimens, and they were then characterized morphologically and genotypically. In addition, the complete sequences of the BHM26 and BJ50 genomes were determined and were submitted to the GenBank database under accession nos. HQ917060 and HQ917061, respectively. By phylogenetic analysis of the 1C and 1D capsid protein genes, both BHM26 and BJ50 were classified into genotype 2 of the BEV-B cluster. Sequence comparisons of the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR and P1, P2 and P3 subgenomic regions suggested that BHM26 and BJ50 are intergenotypic recombinant BEV isolates.

In general, incongruence between phylogenies of different genome regions is considered indicative of recombination events in enteroviruses [8, 11]. For example, phylogenetic analysis of German BEV isolate D 14/3/96 yielded incongruent results [15] in which comparisons of 1B and 1C indicated a similarity with genotype 2 of the BEV-A cluster; however, in the 1D comparison, the D 14/3/96 strain clustered with genotype 1. Another example of intragenotypic recombination is shown by the LC-R4 strain, which was grouped with the Vir 404/03 strain in the 1B phylogeny but with the VG(5)27 strain in the 1C and 1D phylogenies [15]. These findings are an indication of intergenotypic or intragenotypic recombination in the evolution of the BEVs. In this study, for the China BEV isolates BHM26 and BJ50, sequence analysis based on the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR and P1, P2 and P3 subgenomic regions yielded some incongruent results, suggesting that there were intergenotypic recombination events occurring during evolution of the BHM26 and BJ50 isolates.

The earliest reports concerning the virulence of BEVs suggested that there might be an association between BEV infections and a range of diseases in cattle, as viruses were isolated from cattle with clinical signs that varied from respiratory to enteric to reproductive disease and infertility [1, 14]. However, bovine enterovirus has also been isolated from apparently healthy cattle and wildlife [5, 6, 9]. Interpretation and comparison of these reports are difficult because in many cases other infectious agents were identified or were not investigated. As reviewed by Jiménez-Clavero and co-workers [4], enteroviruses are highly stable in the digestive tract, are shed in large amounts, and persist in the environment for prolonged times, and thus serve as indicators of fecal pollution. In susceptible individuals, enteroviruses cause subclinical infection or mild disease, although occasional infections may cause serious disease, such as the poliomyelitis caused by poliovirus in humans [10]. The BHM26 and BJ50 were isolated from bovine diarrheic fecal samples, but their pathogenicity in cattle experimentally infected with the BHM26 and BJ50 has not been conducted. It is well known that bovine rotavirus and coronavirus are the most important cause of diarrheal diseases in cattle, especially in neonatal calves. If one animal is simultaneously infected by rotavirus and coronavirus, it can cause significant morbidity and mortality. In this study, BEV-specific RNA not only was detected in diarrheic faecal samples (14 of 17 BEV-positive samples collected from diarrheic cattle) but also was detected in healthy faecal samples (3 of 17 BEV-positive samples collected from healthy cattle). At the same time, two other RNA viruses that are transmitted by the fecal-oral route (bovine coronavirus and rotavirus) were detected from diarrheic faecal samples. Although little is actually known regarding the pathogenesis of the Chinese BEV isolates within the enteric tract, according to the epidemiological survey in this study, the BEVs in the fecal specimens from China are only considered to be a minor cause of diarrhea in these dairy farms.

Several characteristics of the BEVs make them good candidates for development of a vaccine vector. First, they are physically very stable, e.g., BEV particles are resistant to lipid solvents (e.g., chloroform) and are stable at pH 2 to 10. Second, BEV is currently considered avirulent in cattle, making it safe to use as a vaccine vector. Third, since enteroviruses enter their host via the enteric tract, they could be administered orally as vaccine vectors to stimulate mucosal immunity. Thus, we are interested in their potential as vaccine vectors for expressing small peptides. We have recently constructed an infectious cDNA clone of the BEV BHM26 isolate on the basis of these sequencing data (Yingli Li et al., unpublished data). Our previous studies have finely mapped a conserved type O FMDV neutralizing epitope recognized by a specific monoclonal antibody [16]. Engineering of recombinant BEVs displaying the FMDV neutralizing epitope in our laboratory is underway for development of a BEV-vectored and epitope-based vaccine.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology (SKLVBP201029) and Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (No. 200803018).

Footnotes

Y. Li and J. Chang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Blas-Machado U, Saliki JT, Duffy JC, Caseltine SL. Bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2-induced meningoencephalitis in a heifer. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:190–194. doi: 10.1354/vp.41-2-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Earle JAP, Skuce RA, Fleming CS, Hoey EM, Martin SJ. The Complete nucleotide sequence of a bovine enterovirus. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:253–263. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-2-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huck RA, Cartwright SF. Isolation and classification of viruses from cattle during outbreaks of mucosal or respiratory disease and from herds with reproductive disorders. J Comp Pathol. 1964;74:346–365. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(64)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimenez-Clavero MA, Escribano-Romero E, Mansilla C, Gomez N, Cordoba L, Roblas N, Ponz F, Ley V, Saiz J-C. Survey of bovine enterovirus in biological and environmental samples by a highly sensitive Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3536–3542. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3536-3543.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B. Fields virology. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowles NJ, Barnett LTR. A serological classification of bovine enteroviruses. Arch Virol. 1985;83:141–155. doi: 10.1007/BF01309912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ley V, Higgins J, Fayer R. Bovine Enteroviruses as indicators of fecal contamination. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3455–3461. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3455-3461.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindberg AM, Andersson P, Savolainen C, Mulders MN, Hovi T. Evolution of the genome of human enterovirus B: incongruence between phylogenies of the VP1 and 3CD regions indicates frequent recombination within the species. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1223–1235. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18971-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy FM, Smith GA, Mattick JS. Molecular characterisation of Australian bovine enteroviruses. Vet Microbiol. 1999;68:71–81. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Racaniello VR. One hundred years of poliovirus pathogenesis. Virology. 2006;344:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santti J, Hyypia T, Kinnunen L, Salminen M. Evidence of recombination among enteroviruses. J Virol. 1999;73:8741–8749. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8741-8749.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shingn M, Chinami M, Taguchi T, Shingu M., Jr Therapeutic effects of bovine enterovirus infection on rabbits with experimentally induced adult T cell leukaemia. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2031–2034. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-8-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyth M, Symonds A, Brazinova S, Martin J. Bovine enterovirus as an oncolytic virus: Foetal calf serum facilitates its infection of human cells. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:49–53. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.10.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor MW, Su R, Cordell-Stewart B, Morgan S, Crisp M, Hodes ME. Bovine enterovirus-1: characterization, replication and cytopathogenic effects. J Gen Virol. 1974;23:173–178. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-23-2-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zell R, Krumbholz A, Dauber M, Hoey E, Wutzler P. Molecular-based reclassification of the bovine enteroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:375–385. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang D, Zhang C, Zhao L, Zhou G, Yu L, Wang H. Identification of a conserved linear epitope on the VP1 protein of serotype O foot-and-mouth disease virus by neutralising monoclonal antibody 8E8. Virus Res. 2011;155:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]