Abstract

We detected a novel feline stool-associated circular DNA virus (FeSCV) in fecal samples from cats with diarrhea using consensus primers matching those of circovirus and cyclovirus. FeSCV is a circular DNA virus containing a genome with a total length of 2,046 nt encoding 2 open reading frames. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that FeSCV is classified into a clade different from that of circovirus and cyclovirus. Since the FeSCVs detected in several cats in the same household had genetically similar genomes, these viruses are most likely derived from the same origin.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00705-018-4020-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Several single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses have been detected by metagenomic analysis in not only animals and plants but also in environmental samples such as sea water and sewage [1]. ssDNA viruses evolve more rapidly than other DNA viruses [2]. Circular replication-associated protein-encoding single-stranded (CRESS) DNA viruses are a type of ssDNA virus. CRESS DNA viruses are the smallest viruses that infect eukaryotic organisms, and the genome of these viruses encodes a replication initiator protein (Rep) and capsid protein (Cap) [3–6]. According to Kazlauskas et al. [6], CRESS DNA viruses of eukaryotes are classified as follows: Anelloviridae, Bacilladnaviridae, Bidnaviridae, Circoviridae, Geminiviridae, Genomoviridae, Nanoviridae, Parvoviridae, and Smacoviridae.

Circovirus and cyclovirus are major animal CRESS DNA viruses belonging to the Circoviridae family. In the intergenic region of circovirus and cyclovirus genomes, the potential stem-loop structure containing a canonical nonanucleotide motif (5’-TAGTATTAC) is present [7]. The stem-loop structure functions as the origin of DNA replication. In Rep, the SF3 helicase motif (Walker-A, Walker-B, and motif C) and rolling-circle replication motifs (RCR I, RCR II, and RCR III) are commonly present [7]. Circoviruses include porcine circovirus 2, which causes post weaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in pigs [8], beak and feather disease (BFD) virus, which causes BFD in psittacines [9], and canine circovirus (CaCV), which causes vasculitis and gastroenteritis in dogs [10]. Cycloviruses include human cyclovirus, which is associated with human acute flaccid paralysis [11], and bat cyclovirus isolated from bat feces [12]. In cats, no Circoviridae family other than feline cyclovirus has been reported. Feline cyclovirus was identified by next-generation sequencing analysis in which the viral gene was detected in a pooled fecal sample collected from 4-5 healthy cats. Its pathogenicity in cats has not been clarified [13]. In this study, we performed nested PCR using Circoviridae family consensus primers and detected novel CRESS DNA viruses in several cats with diarrhea symptoms. The full genomic sequences of these viruses were clarified, and a phylogenetic analysis was performed.

Fecal samples were collected from 20 cats at a private cattery in Japan. These cats were maintained under conditions in which they had contact with each other. Fourteen of the 20 cats developed diarrhea and did not respond to anthelmintics or antibiotics. The remaining 6 cats were healthy. The cats with diarrhea were separated from the other cats, and newly-collected feces were subjected to experiments. Feline coronavirus was detected in fecal samples from 5 healthy cats and 11 cats with diarrhea. In addition, feline bocavirus was detected in fecal samples from 3 cats with diarrhea (Table 1). Other viruses (feline parvovirus, feline rotavirus, feline norovirus, and feline astrovirus) were not detected in the fecal samples. Viral DNA was extracted from the fecal samples using High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Kit (Roche, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nested PCR for detecting Circoviridae family in the feces of cats was performed as described by Li et al. [14]. Briefly, 2 μL of sample DNA was mixed with 15 μL of Quick Taq HS DyeMix (Toyobo, Japan), 0.5 μL of 20 μM consensus degenerate primer mix (first PCR, CV-F1 5’-GGIAYICCICAYYTICARGG and CV-R1 5’-AWCCAICCRTARAARTCRTC; second PCR, CV-F2 5’-GGIAYICCICAYYTICARGGITT and CV-R2 5’-TGYTGYTCRTAICCRTCC CACCA), and 12 μL of distilled water. Using a thermal cycler, DNA was denatured at 95°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 52°C (56°C for the second PCR) for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min with the final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplicons of an expected size (approximately 400 bp) were acquired from the fecal samples from 4 of the 14 cats with diarrhea. Fecal samples were negative for all 6 healthy cats (Table 1; see circovirus and cyclovirus consensus primers). On Blastx analysis, the amino acid sequence homology with known circoviruses and cycloviruses was 34% or lower, whereas the amino acid sequence homology between the samples was 100%, suggesting that the viruses detected in the fecal samples from these 4 cats are identical novel CRESS DNA virus.

Table 1.

Characteristics of feces and state of viral infection in cats

| Cat No | Clinical status | FeSCV (Circovirus-Cyclovirus consensus primer) | FeSCV (FeSCV-specific primer) | Co-infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCoV | FBoV | ||||

| 2017-01 | Normal | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-02 | Normal | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-03 | Normal | − | + | + | − |

| 2017-04 | Normal | − | + | + | − |

| 2017-05 | Normal | − | + | − | − |

| 2017-06 | Normal | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-07 | Diarrhea | + | + | + | − |

| 2017-08 | Diarrhea | + | + | − | + |

| 2017-09 | Diarrhea | + | + | − | − |

| 2017-10 | Diarrhea | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-11 | Diarrhea | − | + | + | + |

| 2017-12 | Diarrhea | − | + | + | − |

| 2017-13 | Diarrhea | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-14 | Diarrhea | + | + | + | − |

| 2017-15 | Diarrhea | − | + | + | − |

| 2017-16 | Diarrhea | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-17 | Diarrhea | − | + | − | + |

| 2017-18 | Diarrhea | − | + | + | − |

| 2017-19 | Diarrhea | − | − | + | − |

| 2017-20 | Diarrhea | − | + | + | − |

FeSCV: feline stool-associated circular virus, FCoV: feline coronavirus, FBoV: feline bocavirus

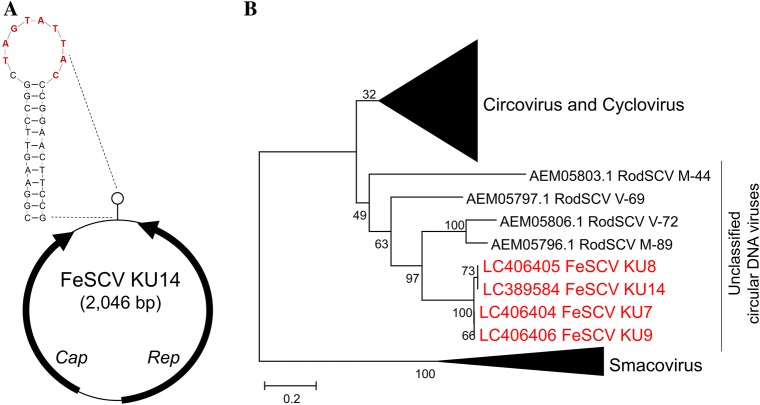

We named the virus detected in this study feline stool-associated circular virus (FeSCV). To determine the complete genomic sequence of FeSCV, inverse primers (CV841F 5’-TTCTCCCGACCTGGACATAG and CV664R 5’-ACAGAGATGATAGCGTCCGG) were prepared based on a section of the base sequence of the acquired Rep gene, and inverse PCR was performed. Fig. S1 shows the schematic position of the inverse PCR primers and other primers used for the FeSCV genome. Prior to inverse PCR, circular DNA was multiplied using TempliPhiTM 100 Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare, USA). Viral DNA was amplified by inverse PCR, which was performed in a total volume of 50 μL using the following mixture: 3 μL of multiplied circular DNA mixed with 10 μL of 5X PrimeSTAR buffer (TaKaRa, Japan), 4 μL of dNTP mixture (TaKaRa, Japan) containing 2.5 mM of each dNTP, 1 μL of 20 μM primer mix (FC1F), 0.5 μL of PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (2.5 U/mL; TaKaRa, Japan), and 31.5 μL of distilled water. Using a thermal cycler, the DNA was amplified at 98°C for 1 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 sec, primer annealing at 55°C for 15 sec, and synthesis at 72°C for 1 min with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. From all samples, approximately 1,800-bp amplicons were acquired. The sequences of the viral genomes were obtained by sequencing the overlapping PCR products (amplicons of 400 and 1,800 bp in size). Phylogenetic trees based on Rep were analyzed using MEGA software (version 6). Phylogenetic relationships were evaluated using the neighbor-joining algorithm, and branching order reliability was analyzed by 1,000 replications of bootstrap resampling. All 4 strains of FeSCV were circular DNA viruses containing a genome with a total length of 2,046 nt encoding 2 open reading frames (ORF) (Fig. 1A). ORF1 (putative Rep gene) was located between 56 nt and 1,015 nt on the complementary strand and presumed to encode 319 aa protein. ORF2 (putative Cap gene) was located between 1,138 nt and 1,878 nt on the sense strand and presumed to encode 246 aa protein. A potential stem-loop structure containing the canonical nonanucleotide motif (5’-TAGTATTAC) was present in the intergenic region. Table 2 shows the conserved motifs in the FeSCV KU14 strain. The presence of all 3 SF3 helicase motifs in the putative Rep of FeSCV was confirmed; however, only RCR III of the RCR motifs was present. A region (RRRYYRRRYVSRPPRRR) presumed to be a classical nuclear location signal (NLS) was detected at the N terminus of the putative Cap. Phylogenetic analysis based on Rep revealed that FeSCV was positioned in a clade different from other known CRESS DNA viruses (Fig. 1B). Of the viruses that infect eukaryotic organisms, those most similar to FeSCV were rodent stool-associated circular viruses (RodSCV). Of note, the putative Rep and putative Cap of FeSCV were approximately 50% homologous with RNA helicase and the hypothetical protein of Giardia intestinalis, respectively. The FeSCV genomes were submitted to GenBank under 3 accession numbers LC389584 (KU14), LC406404 (KU7), LC406405 (KU8), and LC406406 (KU9), respectively.

Fig. 1.

The genomic organization of FeSCV and phylogenetic tree based on Rep amino acid sequences. (A) Predicted circular structure and potential stem-loop structure of the FeSCV KU14 strain. The red letters indicate the canonical nonanucleotide motif. (B) Phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid sequence of full-length Rep. The phylogenetic analysis was based on the deduced amino acid sequence of full-length Rep. Phylogenetic relationships were evaluated using the neighbor-joining method based on Kimura 2 parameter model, and branching order reliability was analyzed by 1,000 replications of bootstrap resampling. The original data without the omission of circoviruses, cycloviruses, and smacoviruses are shown in Fig. S2. RodSCV: rodent stool-associated circular virus

Table 2.

Highly conserved motifs of Rep detected in FeSCV based on the report by Rosario et al. [7]

| Name of region | Sequence of Circoviridae family | Sequence of FeSCV KU14 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH3 helicase motif | Walker A | G(P/x)(P/x)GxGKS | GPSGGGKS |

| Walker B | uuDDF | ILDDF | |

| Walker C | uTSN | ITSN | |

| RCR motif | RCR motif I | FT(L//I)NN | Not detected |

| RCR motif II | PHLQG | Not detected | |

| RCR motif III | YC(S/x)K | YCSK | |

x: any amino acid u: hydrophobic amino acid (F, I, L, V, or M)

Based on the base sequence of FeSCV clarified in this study, specific primers to detect the FeSCV gene (FeSCV1F 5’-GCTAAGGTCTGCCTCAGGTG and FeSCV1R 5’-CTATGTCCAGGTCGGGAGAA) were prepared. PCR was performed as described above except the reaction temperature and time were modified as follows: DNA was amplified at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, primer annealing at 55°C for 45 sec, and synthesis at 72°C for 45 sec with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. When an amplicon with the expected size of 303 bp was detected, the sample was regarded as FeSCV-positive. Of the 14 cats with diarrhea, 10 were FeSCV-positive (71.4%). Three of the 6 healthy cats were FeSCV-positive (50.0%) (Table 1; see FeSCV-specific primer).

To detect feline circovirus or feline cyclovirus in feline fecal samples, nested PCR using Circoviridae consensus primers was performed. The degenerate primers used in this nested PCR assay were prepared based on the consensus sequence of the Rep gene in 12 strains of circoviruses and one strain of cyclovirus [14] since we expected only circoviruses and cycloviruses to be detected. However, a novel CRESS DNA virus, FeSCV, was detected in the fecal samples. Phylogenetic analysis based on Rep revealed that FeSCV belongs in a clade different from that of circoviruses and cycloviruses for which the reason is unclear.

Very few known CRESS DNA viruses, including circoviruses, have been confirmed to have pathogenicity in the host. Moreover, many studies on novel CRESS DNA viruses analyzed only viral genes, that is, only a few studies analyzed whether the viral infection is manifested in the host. The FeSCV found in this study was detected in 13 of the 20 cats. Based on this result, cats may be the natural host of FeSCV. Furthermore, the 4 FeSCVs (KU7 strain, KU8 strain, KU9 strain, and KU14 strain) are genetically similar and share approximately 100% of their genomes. This data suggests that these FeSCVs have the same origin. The FeSCV infection rates in healthy cats and cats with diarrhea were 50.0 and 71.4%, respectively and demonstrate that although the infection rate was slightly higher in cats with diarrhea, half of the healthy cats were also infected with FeSCV. Thus, it is unclear whether FeSCV is pathogenic. Furthermore, the rate of co-infection with FeSCV and other viruses was approximately 2-fold higher in cats with diarrhea (64.2%) than in healthy cats (33.3%). In dogs, a relationship between CaCV and gastroenteritis has been suggested. Dowgier et al. [15] reported that CaCV infection and the development of acute gastroenteritis were correlated in dogs co-infected with other enteric viruses. The incidence of enteritis may increase when FeSCV-infected cats are co-infected with other viruses. Further investigation of FeSCV pathogenicity in cats is necessary.

The putative Rep of FeSCV was 50% homologous with RNA helicase of Giardia intestinalis in Blastx analysis, and the putative Cap of FeSCV was approximately 45% homologous with a cysteine protease (hypothetical protein) of Giardia intestinalis. We first suspected that the FeSCV gene identified in this study was derived from Giardia intestinalis. However, we concluded that FeSCV is a circular DNA virus based on the following: 1) No Giardia intestinalis was detected in the fecal test, and 2) the complete genome of FeSCV was amplified using the rolling-circle amplification and inverse PCR assays. Similar with FeSCV, RodSCV is reported to have Rep with <52% homology with RNA helicase of Giardia intestinalis [16]. Moreover, both the putative Rep and putative Cap of FeSCV are similar to proteins derived from Giardia intestinalis. To our knowledge, no study has reported a gene encoding Cap or putative Cap of CRESS DNA virus generated by recombination with parasitic or bacterial genes. Further investigation is necessary for the origin of the putative Cap of FeSCV.

A region presumed to be a classical NLS was detected in the putative Cap of FeSCV. As circoviruses lack DNA polymerase, virus particles have to transfer into the nucleus for viral DNA replication [17]. In BFDV and duck circoviruses, viral DNA may by transported into the host cell nucleus via NLS-containing viral Cap [18, 19]. It is unclear whether the putative Cap of FeSCV functions similar to the Cap of BFDV and duck circoviruses. Further studies regarding the intracellular localization of FeSCV putative Cap is required.

We detected a novel CRESS DNA virus, FeSCV, in fecal samples from cats. Although it was detected using consensus primers of circovirus and cyclovirus, FeSCV was phylogenetically positioned in a clade different from that of these viruses. FeSCV was detected in several cats that were housed together, suggesting that FeSCVs are derived from the same origin. In addition, FeSCV is considered to cause diarrhea in cats via co-infection with other enteric viruses. Therefore, it is necessary to perform a large-scale epidemiological survey and clarify whether diarrhea is associated with FeSCV infection.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Fig. S1: A schematic representation of the position of the primers on the FeSCV genome. The relative positions of the primers used in this study are indicated by arrows with primer names (TIFF 4754 kb)

Fig. S2: The original data of the phylogenetic tree based on FeSCV and Rep amino acid sequences (TIFF 7697 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was in part supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI Grant number JP16K08027.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed by the authors. Samples were obtained from an animal hospital, and this study does not include animal experiments.

References

- 1.Simmonds P, Adams MJ, Benkő M, Breitbart M, Brister JR, Carstens EB, et al. Consensus statement: virus taxonomy in the age of metagenomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(3):161–168. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiewsakun P, Katzourakis A. Time-dependent rate phenomenon in viruses. J Virol. 2016;90(16):7184–7195. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00593-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaszab E, Marton S, Forró B, Bali K, Lengyel G, Bányai K, et al. Characterization of the genomic sequence of a novel CRESS DNA virus identified in Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius) Arch Virol. 2018;163(1):285–289. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui L, Wu B, Zhu X, Guo X, Ge Y, Zhao K, et al. Identification and genetic characterization of a novel circular single-stranded DNA virus in a human upper respiratory tract sample. Arch Virol. 2017;162(11):3305–3312. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Li S, Mahmood A, Yang S, Wang X, Shen Q, et al. Plasma virome of cattle from forest region revealed diverse small circular ssDNA viral genomes. Virol J. 2018;15(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12985-018-0923-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazlauskas D, Varsani A, Krupovic M. Pervasive chimerism in the replication-associated proteins of uncultured single-stranded DNA viruses. Viruses. 2018;10(4):187. doi: 10.3390/v10040187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosario K, Breitbart M, Harrach B, Segalés J, Delwart E, Biagini P, Varsani A. Revisiting the taxonomy of the family Circoviridae: establishment of the genus Cyclovirus and removal of the genus Gyrovirus. Arch Virol. 2017;162(5):1447–1463. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3247-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olvera A, Cortey M, Segales J. Molecular evolution of porcine circovirus type 2 genomes: phylogeny and clonality. Virology. 2007;357(2):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie PA, Anderson IL, Lambert DM. Evidence for specificity of psittacine beak and feather disease viruses among avian hosts. Virology. 2003;306(1):109–115. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(02)00048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, McGraw S, Zhu K, Leutenegger CM, Marks SL, Kubiski S, et al. Circovirus in tissues of dogs with vasculitis and hemorrhage. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(4):534. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.121390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smits SL, Zijlstra E, van Hellemond JJ, Schapendonk CM, Bodewes R, Schürch AC, Osterhaus AD. Novel cyclovirus in human cerebrospinal fluid, Malawi, 2010–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(9):1511. doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Victoria JG, Wang C, Jones M, Fellers GM, Kunz TH, et al. Bat guano virome: predominance of dietary viruses from insects and plants plus novel mammalian viruses. J Virol. 2010;84(14):6955–6965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00501-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Li L, Deng X, Kapusinszky B, Pesavento PA, Delwart E. Faecal virome of cats in an animal shelter. J Gen Virol. 2014;95(11):2553–2564. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.069674-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Kapoor A, Slikas B, Bamidele OS, Wang C, Shaukat S, et al. Multiple diverse circoviruses infect farm animals and are commonly found in human and chimpanzee feces. J Virol. 2010;84(4):1674–1682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowgier G, Lorusso E, Decaro N, Desario C, Mari V, Lucente MS, et al. A molecular survey for selected viral enteropathogens revealed a limited role of Canine circovirus in the development of canine acute gastroenteritis. Vet Microbiol. 2017;204:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan TG, Kapusinszky B, Wang C, Rose RK, Lipton HL, Delwart EL. The fecal viral flora of wild rodents. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002218. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faurez F, Dory D, Grasland B, Jestin A. Replication of porcine circoviruses. Virol J. 2009;6(1):60. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson EI, Dombrovski AK, Swarbrick CM, Raidal SR, Forwood JK. Structural determination of importin alpha in complex with beak and feather disease virus capsid nuclear localization signal. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;438(4):680–685. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang QW, Zou JF, Wang X, Sun YN, Gao JM, Xie ZJ, et al. Identification of two functional nuclear localization signals in the capsid protein of duck circovirus. Virology. 2013;436(1):112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1: A schematic representation of the position of the primers on the FeSCV genome. The relative positions of the primers used in this study are indicated by arrows with primer names (TIFF 4754 kb)

Fig. S2: The original data of the phylogenetic tree based on FeSCV and Rep amino acid sequences (TIFF 7697 kb)