Abstract

A strain of transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), SHXB, was isolated in Shanghai, China. The complete genome of strain SHXB was sequenced, and its sequence was compared those of other TGEV strains in the GenBank database. The comparison showed that there were no insertions or deletions in the 5′ and 3′- non-translated regions, in the nonstructural genes ORF1, ORF3, and ORF7, or in the genes encoding the structural proteins envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleoprotein (N). A phenomenon in common with other strains was that nucleotide (nt) 655 of the spike (S) gene was G, and a common change in nt 1753 of the S gene was a T-to-G mutation that caused a serine-to-alanine mutation at amino acid 585, which is in the region of the main major antigenic sites A and B of the TGEV S protein. A 6-nt deletion was also found at nt 1123-1128 in all Purdue strains except the strain Virulent Purdue. Phylogenetic analysis showed that TGEV SHXB was closely related to the Purdue strains and shared a common ancestor with the Miller strains as well as strain PRCV-ISU-1.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2080-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Nonstructural Protein, ORF3 Gene, Strain Group, Homology Comparison, Replicase Gene

Introduction

Porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) is an enteropathogenic coronavirus. Like other coronaviruses, it is a pleomorphic enveloped virus that contains a large, positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome [20]. It is a major pathogen that replicates in the cytoplasm of villous epithelial cells in the small intestine, leading to severe villous atrophy and malabsorptive diarrhea and resulting in significant economic losses in the swine industry, where the mortality rates may reach 100% in the newborn piglets [23]. TGEV was identified as an etiological agent of transmissible gastroenteritis in swine in the United States in 1946 [7] and was reported in many swine-producing countries between the late 1970s and the 1980s, including England, Japan, China, Belgium, Africa and Australia [13, 28, 34]. The genomic sequence length is about 28.5 kb [33]. The genome contains nine open reading frames (ORFs) encoding four structural proteins (spike [S], envelope [E], membrane [M] and nucleoprotein [N]) and five nonstructural proteins (replicase 1a and 1b, 3a, 3b, and protein 7) arranged in the genome in the order 5′-replicase (1a/1b)-S-3a-3b-E-M-N-7-3′ [9].

About two-thirds of the coronavirus genome is devoted to encoding the viral replicase, which mediates coronavirus replication, transcription and translation [21]. The ORF1 region of the replicase gene is composed of two opening frames, ORF1a and ORF1b, and the translation of the ORF1a/1b polyprotein involves an efficient ribosomal frameshifting activity [27]. The S protein is highly glycosylated and is believed to be the viral attachment protein. It interacts with porcine aminopeptidase N, which acts as a cell receptor for TGEV [17]. The interaction between coronavirus S protein and eIF3f plays a functional role in controlling the expression of host genes, especially genes that are induced during coronavirus infection [35]. PRCV has a large deletion in the S gene, resulting in the loss of major antigenic sites B and C in the S protein [10]. The cell-culture-passaged TGEV strain TOY56 has point mutations in the spike gene that cause a shift from intestinal to respiratory tract tropism [29]. The mutation in the spike protein may be an important indicator for evaluating the tropism and virulence of TGEV. The M protein, the main virion membrane protein, is mainly embedded in the lipid vesicle membrane and is connected to the capsular membrane during viral nucleocapsid assembly [15]. The E protein is a membrane-spanning protein, while the N protein is found within the viral membrane. The N protein has been shown to interfere with interferon signaling through various mechanisms [16, 19]. It has also been observed that the N protein of several coronaviruses can localize in the nucleolus, where it may perturb cell cycle activities of the host cell for the benefit of viral mRNA synthesis [6, 37]. The ORF3 is composed of two opening frames, ORF3a and ORF3b, and deletions in ORF3a are found in many TGEV strains and strain PRCV [14, 22]. Some studies have suggested that while ORF3a is not essential for virulence, the deletion of this gene may affect viral virulence and tissue tropism [32]. The ORF7 counteracts host-cell defenses and affects TGEV persistence, increasing TGEV survival through the negative modulation of downstream caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways [3, 4].

The objective of this study was to determine the complete genomic sequence of strain TGEV SHXB isolated in Shanghai, China. To distinguish strain TGEV SHXB from other domestic and international strains at the molecular level, we analyzed the differences between the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of structural and nonstructural proteins of the TGEV strains as well as the PRCV strain ISU-1. This will enhance our understanding of the evolution of coronaviruses and lay the foundation for further development of a genetically engineered TGEV vaccine.

Materials and methods

Virus, cell culture, and virus passages

TGEV SHXB was isolated from porcine intestinal contents. STC cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, HyClone, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO) and were maintained in maintenance medium (DMEM supplemented with 2 % FBS) at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator. Strain SHXB was passaged ten times in STCs.

Extraction of genomic TGEV RNA and RT-PCR

When virus-infected STCs showed 70-80 % cytopathic effect (CPE), cell culture flasks were frozen and thawed three times, and cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation for 20 min at 7000 × g. Culture supernatants from infected cells were collected and used for preparation of viral RNA. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA pellet was washed with 1 ml of 75 % alcohol, collected by centrifugation for 10 min at 8000 × g, and dried for about 5 min, and the resulting RNA pellet was resuspended in 20 µl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated deionized water. Viral cDNA was generated by reverse transcription using PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Extraction of the viral genome sequence

Specific oligonucleotide primers were designed based on the sequence information available in GenBank for TGEV strains H16 (FJ755618.2) as a reference genome (Table S1). As the virus sequence is too long to clone in its entirety, the viral genome was divided into 27 segments. The length of each segment was 1000-1500 nt, and there was 200-to 400-nt overlap between segments. Primers were designed using Primer 5. For amplification of the TGEV subclones, reactions were carried out in a total volume of 50 µl containing 10 µl of 5× Q5 reaction buffer, 4 µl of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.5 µl of Q5 fidelity polymerase (New England BioLabs), 2.5 µl of each specific primer, 1 µl of viral cDNA and sterile deionized water. The PCR protocol was as follows: denaturation for 30 seconds, followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 7 s, 55-72 °C for 15 s, depending on the primers used, based on optimal annealing temperatures predicted using NEB Tm Caculator (www.neb.com /Tm Caculator), and 72 °C for several minutes, depending on the size of the PCR product, and finally, an elongation step at 72 °C for 2 min. The 5′ and 3′ ends of the viral genome were confirmed by rapid amplification of cDNA ends using a 3′ and 5′-Full RACE Core Set with PrimeScript (TakaRa). The PCR products were purified using a Gel Extraction Kit (Omega), cloned into the pJET1.2 vector (Thermo), and used to transform E. coli DH5α. Three positive bacteria (colony PCR validation) were sequenced by Invitrogen.

Sequence analysis

Sequence data were assembled and analyzed using Lasergene software. Multiple sequence alignments were made using the Clustal W method. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method using the MegAlign program from the DNASTAR software package (Version 7.1.0, DNASTAR Inc., USA). The reliability of the neighbor-joining tree was estimated by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates. The nucleotide and the amino acid sequences of strain TGEV SHXB were compared with the corresponding sequences of TGEV strains in the GenBank database. Sequences were analyzed using the computer program MEGA version 5.0. The TGEV strains used in this study were – Virulent Purdue, DQ811789; Purdue P115, DQ811788; PUR46-MAD, NC_002306; Miller M60, DQ811786; Miller M6, DQ811785; SC-Y, DQ443743; TS, DQ201447; H16, FJ755618; Attenuated H, EU07421; WH-1, HQ462571.1; PRCV- ISU-1, DQ811787.1.

Results

Complete genome sequence of TGEV SHXB

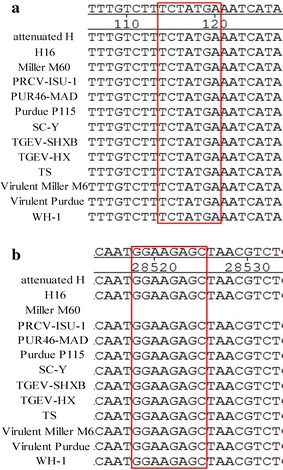

The full-length genome sequence of strain SHXB was deduced by combining the sequences of several overlapping cDNA fragments. The genome sequence of strain SHXB was 28,571 nucleotides (nt) long, including the poly A tail. The 5′ portion of the genome (nt 1-20,368) contained the 314-nt non-translated region (NTR), ORF1a (nt 315-12,368), and ORF1b (nt 12,326-20,368) encoding the viral RNA-dependent RNA replicase. The structural proteins S, E, M and N were found to be encoded by ORFs S (nt 20,365-24,708), E (nt 25,857-26,110), M (nt 26,035-26,904), and N (nt 26,917-28,065), respectively. The three non-structural proteins were ORF3a (nt 24,827-25,042), ORF3b (nt 25,136-25,870), ORF7 (nt 28,071-28,307), respectively. The 5’ NTR consisted of 314 nt and included a potential short AUG-initiated ORF (nt 114-121), beginning within a Kozak context (UCUaugA) (Fig. 1a). The 3′ end of the genome contained a 264-nt untranslated sequence and the poly (A) tail. At nt 106-113 upstream from the poly(A) tail, there was an octameric sequence of “GGAAGAGC” (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

(a) The 5′ NTR and a potential short AUG-initiated ORF beginning within a Kozak context (UCUaugA). (b) Octameric sequence of “GGAAGAGC” upstream of the poly(A) tail in all strains except strain Miller M60

The non-structural genes

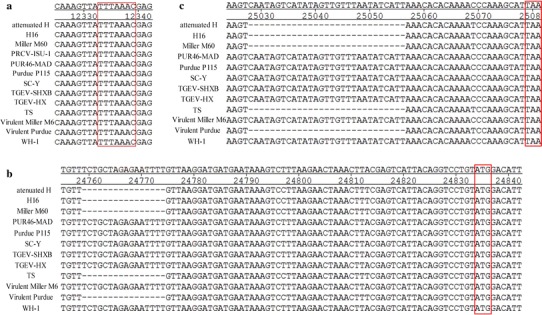

The replicase genes were composed of ORF1a and ORF1b, which contained a 43-nt common region and included a typical coronavirus “slippery site” (5′-UUUAAAC-3′, nt 12,333-12,339; Fig. 2a), which allows the ORF1a translation termination site to be bypassed and an additional ORF, ORF1b to be read. As has been shown for other TGEV coronavirus [8], the ORF1a gene of strain SHXB was predicted to encode a protein of 4,017 aa, and the ORF1b gene was predicted to encode a protein of 2,680 amino acids. Nucleotide sequence analysis indicated that there were no deletions or insertions in the ORF1ab region of any of the TGEV strains. The ORF1a of strain PRCV-ISU had a 3-amino-acid deletion (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

(a) A typical coronavirus “slippery site” 5′-UUUAAAC-3′, found in all TGEV strains. (b) A 16-nt deletion before the initiation codon “ATG”, found in strains attenuated H, H16, Miller M60, TS, and Virulent Purdue. (c) A 29-nt deletion before stop codon “TAA”, found in strains attenuated H, H16, Miller M60, TS, and Virulent Purdue

Table 1.

Length in amino acids of the predicted structural and nonstructural proteins of twelve TGEV strains and PRCV-ISU-1

| TGEV | PRCV- ISU-1 |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHXB | Virulent Purdue | P115 | Pur46-MAD | WH-1 | SC-Y | Miller M6 | Miller M60 | HX | TS | H16 | Attenuated H | ||

| Replicase 1a | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4017 | 4014 |

| Replicase 1b | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 | 2680 |

|

S ORF3a |

1447 | 1449 | 1447 | 1447 | 1447 | 1447 | 1449 | 1448 | 1447 | 1449 | 1448 | 1448 | 1222 |

| 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 71 | - | |

| ORF3b | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 67 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 205 |

| E | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 |

| M | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 264 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 261 |

| N | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 | 382 |

| ORF7 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 |

ORF3a and ORF3b of strain SHXB were predicted to encode proteins of 72 and 244 amino acids, respectively. In strain Miller M60, a 531-nt deletion in the ORF3b gene results in the ORF3b-encoded protein 67 amino acid being truncated; in strain PRCV-ISU, a 184-nt deletion in the ORF3a gene disrupts the predicted ORF3a-encoded protein, and a 117-nt deletion in the ORF3b gene caused the predicted ORF3b encoded protein was shorter than other TGEV strains [36]. As shown in Fig. 2b, a 16-nt deletion before the initiation codon “ATG” found in strains attenuated H, H16, Miller M60, TS, and Virulent Purdue, and a 29-nt deletion before the stop codon “TAA” were also found in these strains (Fig. 2c). No deletions or insertions were found in the ORF3a or ORF3b gene of strain SHXB. The ORF7 gene of strain SHXB was predicted to encode 78 amino acids, and no deletions or insertions were found in comparison to other TGEV strains and strain PRCV-ISU-1 (Table 1).

The structural genes

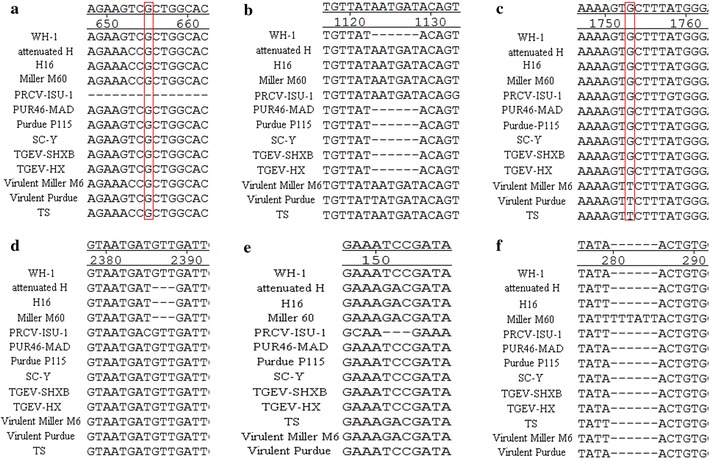

The nucleotide sequence of the S gene of strain SHXB was 4,344 nt in length, encoding a predicted protein of 1,447 amino acids. It had the same length as those of strains Purdue P115, Pur46-MAD, WH-1, TGEV-HX, and SC-Y (Table 1). At position 655 of all TGEV strains, the nucleotide was G (Fig. 2a). A 6-nt deletion was found in the S gene at position 1,123-1,128 of strains SHXB, Purdue P115, PUR46-MAD, WH-1, SC-Y, and TGEV-HX (Fig. 3b), which caused the S protein to be two amino acids shorter than in strains Virulent M6, Virulent Purdue, and TS (Table 1). At nt position 1,753 of strains Virulent M6, Virulent Purdue, and TS, the nucleotide was T, while in the other strains, it was G (Fig. 3c). A 3-nt deletion was found in the S gene, at position 2,386-2,388 of strains attenuated H, H16, and Miller M60 (Fig. 3d), which caused a one-amino-acid deletion in the S protein compared to strains Virulent M6, Virulent Purdue, and TS (Table 1), while it was not found in strain SHXB. Sequence analysis confirmed a previous report of a 681-nt deletion in the 5′ end of the S gene of PRCV-ISU [24, 36].

Fig. 3.

(a) A guanine (G) at position nt 655 of all TGEV strains. (b) A 6-nt deletion in the S gene at nt position 1123-1128 of strains SHXB, Purdue P115, PUR46-MAD, WH-1, SC-Y, and TGEV-HX. (c) A thymine (T) residue at position nt 1753 of strains Virulent M6, Virulent Purdue, and TS and G in the other strains. (d) A 3-nt deletion in the S gene, at nt position 2386-2388 of strains attenuated H, H16, and Miller M60. (e) A 3-nt deletion at position 151-153 in the M gene of strain PRCV-ISU-1. (f) A 6-nt insertion in the M gene of Miller M60 compared with other TGEV strains

Sequence analysis revealed no deletions or insertions in the E and N genes of any of the TGEV strains or strain PRCV-ISU-1. The predicted E and N proteins were 82 and 382 amino acids long, respectively (Table 1). At nt position 151-153, there was a 3-nt deletion in the M gene of strain PRCV-ISU-1 (Fig. 3e), making it one amino acid shorter than those of the other strains. There was a 6-nt insertion in the M gene of Miller M60 when compared with other TGEV strains (Fig. 2f), making it two amino acids longer than that of the other strains (Table 1).

Homology comparisons

To investigate the homology of strain SHXB to other TGEV strains and PRCV-ISU-1, the nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences of the nonstructural and structural protein genes (replicase ORF1, S, 3a, 3b, E, M, N, ORF7) of strain SHXB were compared. As shown in Table 2, the amino acid sequence identity in ORF1 was 96.7 %-100 %; in protein S it was 97.7 %-100 %; in ORF3a it was 86.1 %-100 %; in ORF3b it was 44.1 %-100 %; in protein E it was 91.6 %-98.8 %; in protein M it was 96.2 %-99.7 %; in protein N it was 97.9 %-99.7 %; and in protein ORF7, it was 94.9 %-97.5 %. Interestingly, when comparing the amino acid sequences of ORF3a, strain SHXB showed 100 % sequence identity to strains PUR16-MAD, Purdue P115, SC-Y, TGEV-HX, and WH-1, and showed 98.9 % identity to strain Virulent Purdue, but showed less than 90 % to strains Attenuated H, H16, Miller M6, Miller M60, and TS. Protein N showed the highest amino acid similarity. A 531-nt deletion in the ORF3b gene of Miller M60 resulted in 44.1 % amino acid similarity to strain SHXB.

Table 2.

Nucleotide and amino acids sequence identity of the genomes of TGEV SHXB to other TGEV strains and PRCV-ISU-1(%)

| ORF1 | S | ORF3a | ORF3b | E | M | N | ORF7 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | |

| Attenuated H | 98.9 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 97.9 | 92.6 | 87.5 | 98.9 | 97.6 | 968 | 91.6 | 98.0 | 96.9 | 98.0 | 98.2 | 97.5 | 96.2 |

| H16 | 98.9 | 98.2 | 98.4 | 98.1 | 93.1 | 88.9 | 99.0 | 98.0 | 976 | 94.0 | 98.2 | 97.2 | 98.1 | 98.2 | 97.5 | 96.2 |

| Miller 6 | 99.0 | 98.4 | 98.5 | 98.2 | 93.0 | 88.9 | 99.0 | 98.0 | 980 | 94.0 | 98.3 | 97.6 | 98.1 | 98.2 | 97.0 | 96.2 |

| Miller 60 | 99.0 | 98.3 | 98.4 | 98.1 | 92.6 | 87.5 | 57.4 | 44.1 | 98.0 | 94.0 | 98.3 | 97.6 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.0 | 94.9 |

| PUR46-MAD | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 98.8 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| Purdure P115 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.6 | 98.8 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| SC-Y | 99.6 | 99.3 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.6 | 98.8 | 99.8 | 99.3 | 99.8 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| TGEV-HX | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 98.8 | 99.8 | 99.3 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| TS | 98.9 | 98.0 | 98.3 | 97.9 | 92.1 | 86.1 | 98.6 | 96.7 | 98.4 | 95.2 | 98.0 | 96.9 | 98.0 | 97.9 | 97.5 | 96.2 |

| Virulent Purdue | 99.9 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.2 | 99.5 | 98.6 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 99.2 | 97.6 | 99.8 | 99.3 | 99.7 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| WH-1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.6 | 98.8 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| PRCV-ISU-1 | 97.8 | 96.7 | 96.2 | 97.7 | – | – | 97.2 | 93.7 | 96.8 | 95.2 | 97.5 | 96.2 | 95.9 | 96.6 | 95.4 | 96.2 |

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities were determined with DNASTAR software using the ClustalW program

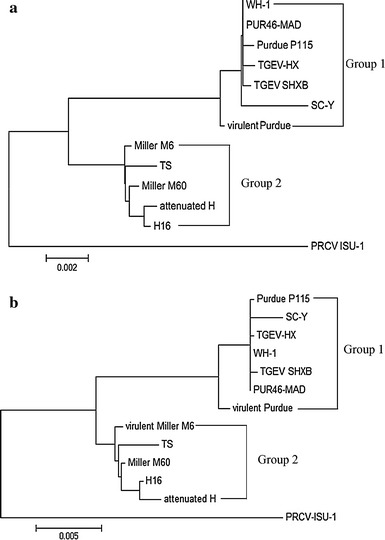

Phylogenetic analysis

Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the entire genomic nucleotide sequences of TGEV strains, all TGEV strains were divided into two groups. One group consists of Purdue strains, and the other of Miller strains. To further explore the evolutionary relationships among these TGEV strains and strain PRCV-ISU-1, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the nucleotide sequence of the S structural protein. As shown in Fig. 4b, strain SHXB also had a close relationship to strains Purdue P115, TGEV-HX, WH-1, and PUR46-MAD. Overall, strain SHXB belongs to Purdue strains group and is more distant evolutionarily from the Miller strains group and strain PRCV-ISU-1, but all of these strains appear to share a common ancestor.

Fig. 4.

(a) Phylogenetic analysis of the complete genome sequences of the strain SHXB, other TGEV reference strains, and strain PRCV-ISU-1. (b) Phylogenetic analysis of the S protein of strain SHXB, other TGEV reference strains, and strain PRCV-ISU-1. Both of these phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method with the MegAlign program

Discussion

We sequenced the complete genome of strain TGEV SHXB. To investigate the differences in their genetic structure, diversity and evolution, TGEV SHXB was compared with other TGEV strains and the ISU-1 strain of PRCV. Some researchers had reported detailed comparisons of the sequences of TGEV strains, and these results will give a reference for us to understand the changes in virulence of SHXB. Compared with the coronavirus PEDV, the number of complete sequences of TGEV in public databases is limited. Before the present study, there were twelve complete genomic sequences of TGEV strains in GenBank. Analyzing the whole genomic sequence of SHXB will help provide information about its genetic structure, diversity, and evolution, and in particular, the epidemic characteristics of the coronavirus in China.

The 5′ and 3′ NTRs of TGEV are critically important for viral replication and transcription [1]. In this study, no deletions or insertions were found in 5′ and 3′-NTR regions of strain SHXB, suggesting that the replication and transcription mechanism of strain SHXB was not changed. We found a homopolymeric “slippery” sequence of nucleotides (5′-UUUAAAC-3′) and a pseudo-knot structure, which is critical for the transcription of the ORF1ab gene and involves ribosomal frame shifting [2]. These elements were also found in strain SHXB.

A similar nucleotide change in the S protein has been reported previously. It was shown that a G residue at position 655 of the S protein was essential for maintaining enteric tropism of the TGEV strain PUR46-MADand mutation of this nucleotide caused a shift in tropism from enteric to respiratory [30]. As shown in Fig. 3a, at position 655, all TGEV strains contain a G, except strain PRCV-ISU-1, showing that strain SHXB is an enteric virus. Antigenic site A/B has been mapped to aa 506-706 of the spike protein [11]. At nt position 1753, a T-to-G mutation caused a serine-to-alanine mutation at amino acid 585, which is located in the main major antigenic sites A/B of the TGEV S protein [5]. This change may significantly influence receptor binding or interactions with neutralizing antibody. A single amino acid change in the S protein can have a significant effect on antigenicity [36]. Analyzing the S gene sequence of strain SHXB, we found that the nucleotide at position 1753 was G, indicating that the antigenicity of the S protein may be changed. There was a 6-nt (nt 1,223 to 1,228) deletion in the Purdue strains group, except strain Virulent Purdue, but not in the Miller strains group, strain PRCV-ISU-1, and strain PUR46-MAD. Purdue P115 is attenuated, and this deletion may also play a role in attenuation and is a distinguishing mark of the attenuated Purdue strains group. The same deletion was found in the S protein of attenuated Purdue strain PUR46-C8 but was not found in strain PUR46-C11, which was maintained in vivo [26]. This phenomenon should be investigated by generating specific mutants by reverse genetics, followed by animal experiments.

There were two large deletions (16 and 29 nt, respectively) in the ORF3a gene of strains H16, TS, and Virulent Purdue, and attenuated strains H and Miller M60. Some researchers have found the phenomenon of large nucleotide deletions in the ORF3 gene [22], indicating that deletions in the ORF3 gene may affect the virulence of TGEV [25], but some researchers have found that these deletions in ORF3 gene do not affect virus replication [18], and this suggests that the ORF3a gene is not necessary for viral replication and has a minor effect in the virulence of virus [32]. Two large deletions were only found in the Miller strains group, except strain Virulent Purdue, a phenomenon that may also distinguish between the Miller strains group and the Purdue strains group.

An accumulation of point mutations has been proposed to be a driving force for coronavirus evolution [29]. These mutations and recombination lead to the generation of new coronaviruses and may alter their pathogenicity, change tissue tropism, and even break the barrier between host species. The SARS-CoV-like coronaviruses of bats may have potentially become adapted to humans through genomic mutation and recombination events either directly or via intermediate hosts [12]. The evolution and tissue tropism shift between strains TGEV and PRCV had been described previously [31]. Homology comparisons and phylogenetic analysis help us to understand the evolution of strain SHXB, and homology comparisons showed that strains PUR46-MAD, Purdue-P115, SC-Y, TGEV-HX, Virulent Purdue, and WH-1 are highly similar to SHXB. The nucleotide and amino acid sequence homology of structural proteins and non-structural proteins between 97 %-100 %, especially in the ORF3a gene, showed significant species specificity. Phylogenetic analysis also showed that strain SHXB is closely related to with strains PUR46-MAD, Purdue-P115, SC-Y, TGEV-HX, Virulent Purdue and WH-1, which have the same ancestor, and this is consistent with the results of homology comparison. Strain PUR46-MAD is a derivative of Purdue P115, and both were derived from the strain Virulent Purdue, Therefore, these isolates cluster together in the phylogenetic tree. As shown in Fig. 4, the other branch included Miller strains and Chinese strain TS, attenuated H, and H16, which were from different evolutionary group, but all TGEV strains shared a common ancestor with PRCV-ISU-1.

Previous research has revealed that genetic divergence most frequently occurs within the S and ORF3a/3b genes, suggesting that these regions are frequently mutated and that these changes can occur due to RNA recombination when multiple distinct coronaviruses infect the same host. It has also been found that the 5′ and 3′ UTRs are critically important for viral replication and transcription. By comparing these regions with those of other TGEV strains, we have gained further understanding of the genetic structure, diversity, and evolution of strain SHXB, as well as other coronaviruses. Future studies could involve generating specific mutants by using reverse genetics and characterizing these mutants in animal experiments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Grant of PR China (No. 31372465) and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

References

- 1.Brian DA, Baric R (2005) Coronavirus genome structure and replication Coronavirus replication and reverse genetics. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Brierley I, Digard P, Inglis SC. Characterization of an efficient coronavirus ribosomal frameshifting signal: requirement for an RNA pseudoknot. Cell. 1989;57(4):537–547. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90124-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz JL, Sola I, Becares M, et al. Coronavirus gene 7 counteracts host defenses and modulates virus virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(6):e1002090. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Groot R, Baker S, Baric R et al (2012) Family Coronaviridae. In: Virus taxonomy Ninth report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, pp 806–828

- 5.Delmas B, Rasschaert D, Godet M, Gelfi J, Laude H. Four major antigenic sites of the coronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus are located on the amino-terminal half of spike glycoprotein S. J Gen Virol. 1990;71(6):1313–1323. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-6-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dove BK, You JH, Reed ML, Emmett SR, Brooks G, Hiscox JA. Changes in nucleolar morphology and proteins during infection with the coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8(7):1147–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle L, Hutchings L. A transmissible gastroenteritis in pigs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1946;108:257–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eleouet J-F, Rasschaert D, Lambert P, Levy L, Vende P, Laude H. Complete sequence (20 kilobases) of the polyprotein-encoding gene 1 of transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Virology. 1995;206(2):817–822. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enjuanes L, Dediego ML, Alvarez E, Deming D, Sheahan T, Baric R. Vaccines to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-induced disease. Virus Res. 2008;133(1):45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebauer F, Posthumus W, Correa I, et al. Residues involved in the antigenic sites of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus S glycoprotein. Virology. 1991;183(1):225–238. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90135-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godet M, Grosclaude J, Delmas B, Laude H. Major receptor-binding and neutralization determinants are located within the same domain of the transmissible gastroenteritis virus (coronavirus) spike protein. J Virol. 1994;68(12):8008–8016. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8008-8016.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampton T. Bats may be SARS reservoir. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(18):2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.18.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemeny L, Woods R. Quantitative transmissible gastroenteritis virus shedding patterns in lactating sows. Am J Vet Res. 1977;38(3):307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim L, Hayes J, Lewis P, Parwani A, Chang K, Saif L. Molecular characterization and pathogenesis of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) and porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV) field isolates co-circulating in a swine herd. Arch Virol. 2000;145(6):1133–1147. doi: 10.1007/s007050070114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klumperman J, Locker JK, Meijer A, Horzinek MC, Geuze HJ, Rottier P. Coronavirus M proteins accumulate in the Golgi complex beyond the site of virion budding. J Virol. 1994;68(10):6523–6534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6523-6534.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Martínez-Sobrido L, Frieman M, Baric RA, Palese P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and nucleocapsid proteins function as interferon antagonists. J Virol. 2007;81(2):548–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krempl C, Schultze B, Laude H, Herrler G. Point mutations in the S protein connect the sialic acid binding activity with the enteropathogenicity of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. J Virol. 1997;71(4):3285–3287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3285-3287.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Zhang Q, Chen J, et al. Identification of the avian infectious bronchitis coronaviruses with mutations in gene 3. Gene. 2008;412(1):12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Ja Pan, Tao J, Guo D. SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein antagonizes IFN-β response by targeting initial step of IFN-β induction pathway, and its C-terminal region is critical for the antagonism. Virus Genes. 2011;42(1):37–45. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0544-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lum GE (2012) A Novel Immunomodulatory Subunit Vaccine to Combat the Involvement of Bovine Respiratory Coronavirus Infections in Shipping Fever. Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Interdepartmental Program in Animal and Dairy Sciences by Genevieve Elizabeth Lum MS, Louisiana State University

- 21.Masters PS. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGoldrick A, Lowings J, Paton D. Characterisation of a recent virulent transmissible gastroenteritis virus from Britain with a deleted ORF 3a. Arch Virol. 1999;144(4):763–770. doi: 10.1007/s007050050541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moeser AJ, Blikslager AT. Mechanisms of porcine diarrheal disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;231(1):56–67. doi: 10.2460/javma.231.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page KW, Mawditt KL, Britton P. Sequence comparison of the 5’ end of mRNA 3 from transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine respiratory coronavirus. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(3):579–587. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul PS, Vaughn EM, Halbur PG. Pathogenicity and sequence analysis studies suggest potential role of gene 3 in virulence of swine enteric and respiratory coronaviruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;412:317–321. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1828-4_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penzes Z, González JM, Calvo E, et al. Complete genome sequence of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus PUR46-MAD clone and evolution of the Purdue virus cluster. Virus Genes. 2001;23(1):105–118. doi: 10.1023/A:1011147832586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plant EP, Pérez-Alvarado GC, Jacobs JL, Mukhopadhyay B, Hennig M, Dinman JD. A three-stemmed mRNA pseudoknot in the SARS coronavirus frameshift signal. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(6):e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard G. Transmissible gastroenteritis in endemically infected breeding herds of pigs in East Anglia, 1981-85. Vet Record. 1987;120(10):226–230. doi: 10.1136/vr.120.10.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez CM, Gebauer F, Suñé C, Mendez A, Dopazo J, Enjuanes L. Genetic evolution and tropism of transmissible gastroenteritis coronaviruses. Virology. 1992;190(1):92–105. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91195-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sánchez CM, Izeta A, Sánchez-Morgado JM, et al. Targeted recombination demonstrates that the spike gene of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus is a determinant of its enteric tropism and virulence. J Virol. 1999;73(9):7607–7618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7607-7618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saif L. Animal coronaviruses: what can they teach us about the severe acute respiratory syndrome? Revue scientifique et technique-Office international des épizooties. 2004;23(2):643–660. doi: 10.20506/rst.23.2.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sola I, Alonso S, Zúñiga S, Balasch M, Plana-Durán J, Enjuanes L. Engineering the transmissible gastroenteritis virus genome as an expression vector inducing lactogenic immunity. J Virol. 2003;77(7):4357–4369. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4357-4369.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaughn EM, Halbur PG, Paul PS. Sequence comparison of porcine respiratory coronavirus isolates reveals heterogeneity in the S, 3, and 3-1 genes. J Virol. 1995;69(5):3176–3184. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3176-3184.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wood E, Pritchard G, Gibson E. Transmissible gastroenteritis of pigs. Vet Rec. 1981;108(2):41. doi: 10.1136/vr.108.2.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao H, Xu LH, Yamada Y, Liu DX. Coronavirus spike protein inhibits host cell translation by interaction with eIF3f. PloS One. 2008;3(1):e1494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Hasoksuz M, Spiro D, et al. Complete genomic sequences, a key residue in the spike protein and deletions in nonstructural protein 3b of US strains of the virulent and attenuated coronaviruses, transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine respiratory coronavirus. Virology. 2007;358(2):424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong Y, Tan YW, Liu DX. Recent progress in studies of arterivirus-and coronavirus-host interactions. Viruses. 2012;4(6):980–1010. doi: 10.3390/v4060980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.