Abstract

It has been suggested that antibody overproduction plays a role in the pathogenesis of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). However, only a few studies on the B-cell activation mechanism after FIP virus (FIPV) infection have been reported. The present study shows that: (1) the ratio of peripheral blood sIg+ CD21− B-cells was higher in cats with FIP than in SPF cats, (2) the albumin-to-globulin ratio has negative correlation with the ratio of peripheral blood sIg+ CD21− B-cell, (3) cells strongly expressing mRNA of the plasma cell master gene, B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1), were increased in peripheral blood in cats with FIP, (4) mRNA expression of B-cell differentiation/survival factors, IL-6, CD40 ligand, and B-cell-activating factor belonging to the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF), was enhanced in macrophages in cats with FIP, and (5) mRNAs of these B-cell differentiation/survival factors were overexpressed in antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE)-induced macrophages. These data suggest that virus-infected macrophages overproduce B-cell differentiation/survival factors, and these factors act on B-cells and promote B-cell differentiation into plasma cells in FIPV-infected cats.

Keywords: mRNA Expression Level, Alveolar Macrophage, Feline Infectious Peritonitis, Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus, BAFF mRNA

Introduction

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) belongs to group 1 of the family Coronaviridae. FCoV is classified into two biotypes based on differences in pathogenicity: feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV). FECV infection is asymptomatic in cats. In contrast, FIPV infection causes a fatal disease, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). The difference in pathogenicity between FECV and FIPV in cats is considered to be associated with macrophage tropism of the viruses [27, 29]. It has been proposed that FIPV arises from FECV by mutation [11, 26, 37], but the exact mutation and inducing factors have not yet been clarified.

When anti-FCoV antibody-positive cats are inoculated with FIPV, the onset time of FIP is earlier than that in antibody-negative cats, and symptoms are severer [25]. This phenomenon is known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of FIPV infection. A similar phenomenon has been observed with other virus infections, such as dengue and human immunodeficiency virus infections [10, 33, 35]. ADE of FIPV infection has been reported to be induced by antibodies against FIPV spike (S) protein [5, 12, 23]. In ADE-induced macrophages (ADE macrophages), TNF-alpha production increases with viral replication, and this TNF-alpha acts on macrophages and promotes virus receptor (feline aminopeptidase N; fAPN) expression [31].

There are several events suggested to involve anti-FIPV antibodies in FIP development, other than ADE. For example, antibodies produced due to FIPV infection bind to the virus and form immune-complexes [1, 24]. These complexes are deposited in micro blood vessels. Complement binding to the deposit injures the vascular tissue and causes vasculitis (immune-complex-mediated vasculitis). Hyperproteinemia also develops with an increase of gamma-globulin in FIP cats [1]. Moreover, increased levels of interleukin (IL)-6, a cytokine involved in the survival of B-cells and their differentiation into plasma cells, in ascites and culture supernatant of peritoneal exudative cells (PEC) from FIP cats have been reported [8].

This suggests a close involvement of antibodies in FIP pathogenesis. However, the mechanism leading to the alteration of B-cells into plasma cells has not been investigated. Overproduction of the virus and TNF-alpha also occurs in ADE macrophages in FIPV infection [31], but it is not clear whether the production of B-cell differentiation/survival factors, such as IL-6, is involved in the induction of ADE.

In this study, we collected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from FIP cats and analyzed the B-cell surface antigens as well as measured the mRNA expression level of the plasma cell master gene, B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1). We also collected macrophages from FIP cats and measured the expression levels of the viral RNA and mRNA of B-cell differentiation/survival factors: IL-6, CD40 ligand (CD40L), and B-cell-activating factor belonging to the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF). Furthermore, we investigated the relationship between FIPV infection-induced ADE activity of macrophages and IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Type-II FIPV strain 79-1146 (104 TCID50/ml) was administered orally to 6- to 8-month-old, specific-pathogen-free (SPF) cats. Thirteen cats that developed FIP symptoms (FIP cats), such as fever, weight loss, peritoneal or pleural effusion, dyspnea, ocular lesions, and neural symptoms, and thirteen 6- to 8-month-old SPF cats as controls were used in this study. FIP diagnosis was confirmed upon postmortem examination, revealing peritoneal and pleural effusions and pyogranuloma in major organs.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal experiments of Kitasato University.

Cell cultures and virus

Felis catus whole fetus-4 (Fcwf-4) cells was grown in Eagles’ minimum essential medium containing 50% L-15 medium, 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Feline alveolar macrophages and PBMCs were maintained in RPMI 1640 growth medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2 μg/ml of polybrene. Type-II FIPV strain 79-1146 was grown in Fcwf-4 cells at 37°C. FIPV strain 79-1146 was supplied by Dr. M. C. Horzinek of State University Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Antibodies

Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD21 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (anti-canine CD21 homologue of feline CD21 and human CD21: MAb CD2.1D6) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated IgG F(ab′)2 fragments of rabbit anti-feline IgG(anti-feline sIg Ab) were used to stain feline B-cells. PE-conjugated MAb CD2.1D6 was obtained from Serotec Ltd (UK). FITC-conjugate anti-feline sIg Ab was obtained from Rockland Inc. (USA).

MAb 6-4-2 (IgG2a) used in the present study recognizes S protein of type-II FIPV, as demonstrated by immunoblotting [13]. It has been reported that MAb 6-4-2 exhibits a neutralizing activity in Fcwf-4 and CrFK cells, but exhibits an enhancing activity in feline macrophages, depending on the reaction conditions [14].

Separation of PBMCs

Heparinized blood (10 ml) was diluted twofold with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subjected to Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation at 1,700 rpm for 20 min. The PBMC layer was collected, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml.

Flow cytometric analysis

A total of 2 × 106 cells were incubated with PE-conjugated MAb CD2.1D6 or FITC-conjugated anti-feline sIg Ab at 4°C for 45 min. After the cells were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% NaN3, the number of stained cells was determined by counting 5,000 cells on a FACS 440 (Becton Dickinson, USA).

Albumin-to-globulin ratio

For plasma samples, blood was collected from cats using a heparinized syringe and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. The albumin and globulin levels were determined in plasma samples of SPF cats and in FIP cats, using an automatic analyzer. The albumin-to-globulin ratio was calculated by dividing the albumin levels by the globulin levels.

Recovery of alveolar macrophages

Feline alveolar macrophages were obtained from SPF and FIP cats by broncho-alveolar lavage with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), as previously described by Hohdatsu et al. [12].

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation were performed by the method of Takano et al. [30, 32].

Determination of levels of feline GAPDH mRNA, IL-6 mRNA, CD40L mRNA, BAFF mRNA, Blimp-1 mRNA and FCoV N gene expression

cDNA was amplified by PCR using specific primers for feline GAPDH mRNA, IL-6 mRNA, CD40L mRNA, BAFF mRNA, Blimp-1 mRNA, and the FCoV N genes. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. PCR was performed by the method of Takano et al. [30, 32].

Table 1.

Sequences of PCR primers for feline GAPDH, Blimp-1, IL-6, CD40L, BAFF and FCoV N

| Orientation | Nucleotide sequence | Location | Length (bp) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-AATTCCACGGCACAGTCAAGG-3′ | 158–178 | 97 | [4] |

| Reverse | 5′-CATTTGATGTTGGCGGGATC-3′ | 235–254 | |||

| Blimp-1 | Forward | 5′-TTTTGGCGGATCTATTCCAG-3′ | 719–738a | 186 | GenBank accession no. U08185 |

| Reverse | 5′-GCTCTCCGGGATAAGGGTAG-3′ | 943–961a | |||

| IL-6 | Forward | 5′-GCAGAAAACAACCTGAATCTTCG-3′ | 247–270 | 426 | [4] |

| Reverse | 5′-GAGAAAGGAATGCCCGTGAAC-3′ | 651–672 | |||

| CD40L | Forward | 5′-CCCCAAAGGCTACTACACCA-3′ | 423–443 | 191 | GenBank accession no. AF079105 |

| Reverse | 5′-GACTCTCTCGGATCCACTCG-3′ | 594–613 | |||

| BAFF | Forward | 5′-TGCAACTGATTGCAGAC-3′ | 728–744a | 164 | GenBank accession no. NM033622 |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCCCAAAGACATGG-3′ | 939–953a | |||

| FCoV N | Forward | 5′-CAACTGGGGAGATGAACCTT-3′ | 876–895 | 788 | GenBank accession no. X56496 |

| Reverse | 5′-GGTAGCATTTGGCAGCGTTA-3′ | 1,644–1,663 |

aMouse mRNA sequences

Band density was quantified under appropriate UV exposure by video densitometry using Scion Image software (Scion Corporation, USA). IL-6 mRNA, CD40L mRNA, BAFF mRNA, Blimp-1 mRNA, and the FCoV N genes were quantitatively analyzed in terms of the relative density value to the mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Sequencing and analysis of Blimp-1 and BAFF cDNA

PCR products (21 μl) were electrophoresed with DNA markers on a 1.5% agarose gel. Singlet bands were excised and transferred to microtubes, and DNA was purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Germany). The purified DNA was sent to Shimadzu Corporation (Japan) for sequencing, and the partial base sequences of Blimp-1 cDNA and BAFF cDNA were determined. The sequences determined were then analyzed with the GENETYX computer program (Software Development, Japan).

Inoculation of feline alveolar macrophages with FIPV

Equal volumes a viral suspension (FIPV strain 79-1146, 2 × 103 TCID50/0.1 ml) and a MAb 6-4-2 solution were mixed and reacted at 4°C for 1 h, and 0.1 ml of this reaction solution was used to inoculate feline alveolar macrophages (2 × 106 cells) cultured in each well of 24-well multi-plates. As controls, medium alone, virus suspension alone, or MAb 6-4-2 solution alone was added to feline alveolar macrophages. After virus adsorption at 37°C for 1 h, the cells were washed with HBSS and 1 ml of growth medium. The cells and culture supernatant were collected every 24 h thereafter. The cells were used for measurement of the FCoV N genes, IL-6 mRNA, CD40L mRNA, and BAFF mRNA, and the culture supernatant was used for measurement of the virus titer.

Plaque assay

Confluent Fcwf-4 cell monolayers in 24-well multi-plates were inoculated with 100 μl of the sample dilutions. After virus adsorption at 37°C, the cells were washed with HBSS, and 1 ml of growth medium containing 1.5% carboxymethyl cellulose was added to each well. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 2 days, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and stained with 1% crystal violet.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Student’s t test. The data in Fig. 1a and b were also analyzed by the Mann–Whitney test. P values <0.05 were considered to indicate a significant difference between compared groups.

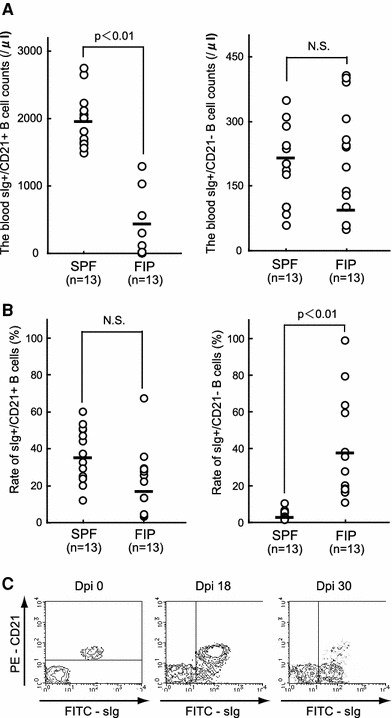

Fig. 1.

Emergence of sIg+ CD21− B-cells after FIPV infection and their counts and ratio in PBMCs: PBMCs were isolated from SPF and FIP cats, and B-cell surface antigens (sIg and CD21 molecules) were analyzed by flow cytometry. a The counts of sIg+ CD21+ B-cells and sIg+ CD21− B-cells in PBMCs, b the ratio of sIg+ CD21+ B-cells and sIg+ CD21− B-cells in PBMCs, c sIg and CD21 antigen expression on the feline B-cell surface upon FIPV infection (Dpi 0), day 18 after FIPV infection (Dpi 18), and the FIP onset time (Dpi 30). N.S. not significant, Dpi day post-inoculation

Results

Emergence of sIg+ CD21− B-cells with FIPV infection and its counts and ratio in PBMCs

The sIg+ CD21+ B-cell counts and sIg+ CD21− B-cell counts at the time of blood sampling are shown in Fig 1a. The blood sIg+ CD21+ count in SPF cats and FIP cats was 1,966.39 ± 254.27 μl−1 (mean ± SD) and 378.97 ± 416.31 μl−1, respectively. The blood sIg+ CD21− count in SPF cats and FIP cats was 194.38 ± 223.49 μl−1 and 89.92 ± 121.42 μl−1, respectively. The ratios of sIg+ CD21+ B-cells and sIg+ CD21− B-cells in PBMCs at the time of blood sampling are shown in Fig. 1b. The ratio of sIg+ CD21+ B-cells in PBMCs was not significantly different between SPF and FIP cats. In contrast, the ratio of sIg+ CD21− B-cells was significantly higher in FIP than in SPF cats. Figure 1c shows the time-course of change in the B-cell surface antigens after experimental FIPV infection. The sIg+ CD21− B-cell ratio gradually increased with time following FIPV infection. sIg+ CD21+ B-cells mostly disappeared at the onset of FIP (30 days after FIPV infection), whereas the ratio of sIg+ CD21− B-cells was markedly increased.

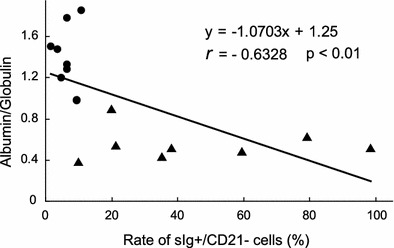

Correlation between the albumin-to-globulin ratio and the ratio of sIg+ CD21− B-cells

By correlation analysis, the albumin-to-globulin ratio showed a negative correlation with the ratio of sIg+ CD21− B-cells in PBMCs of eight SPF cats and eight FIP cats (r = −0.623, P < 0.01). A linear correlation between the albumin-to-globulin ratio and the ratio of sIg+ CD21− B-cells is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the albumin-to-globulin ratio in plasma samples and the ratio of sIg+ CD21− B-cells in PBMCs of cats. Circle SPF cats (n = 8), triangle FIP cats (n = 8)

Partial base sequence analysis of Blimp-1 cDNA, deduction of amino acid sequence, and comparison with other animal species

Tedder et al. [34] reported that CD21 molecules disappeared when B-cells differentiated into antibody-producing cells. Based on this concept, the increased sIg+ CD21− B-cells in PBMC in FIP cats may have been differentiated antibody-producing cells (plasma cells). Thus, we attempted to measure the mRNA expression level of the plasma cell master gene, Blimp-1, in PBMC from FIP cats. Since the base sequence of feline Blimp-1 mRNA has not yet been determined, we partially identified the cDNA base sequence of feline Blimp-1 mRNA.

The nucleotide sequences of mouse (GenBank accession number: MMU08185), human (NM_ 182907), bovine (XM_ 618588), and canine (XM_539068) Blimp-1 mRNA have been determined. Using a highly conserved region, we prepared primers for the detection of feline Blimp-1 mRNA (Table 1). Using these primers, RT-PCR was performed on PBMCs from FIP cats, and a 186-bp band was specifically amplified. This amplified DNA was sequenced, and the base sequence was partially identified (partial base sequence) (data not shown). The amino acid sequence was also deduced from the partial base sequence. Homologies among the partial base sequences of feline, canine, bovine, mouse, and human Blimp-1 mRNA and the deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The percentage of partial nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequences identity of Blimp-1 mRNA and BAFF mRNA between felines and other animals

| Blimp-1 | BAFF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | Nucleotide | Amino acid | ||

| Homology to feline sequence (%) | |||||

| Canine | 98 | 98 | – | – | |

| Bovine | 93 | 97 | 91 | 100 | |

| Mouse | 94 | 100 | 79 | 82 | |

| Human | 96 | 98 | 86 | 93 | |

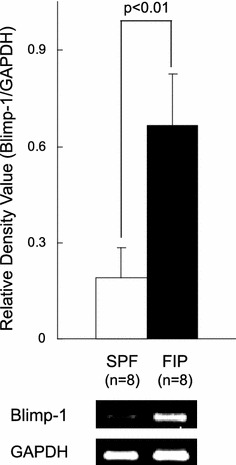

PBMC Blimp-1 mRNA expression level in SPF and FIP cats

The Blimp-1 mRNA expression level in PBMCs was measured in SPF and FIP cats. RT-PCR was performed using feline Blimp-1-specific primers, and the Blimp-1 mRNA expression level in PBMCs was compared between FIP and SPF cats. The Blimp-1 mRNA expression level was significantly elevated in PBMC from FIP cats, compared to that in SPF cats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Blimp-1 mRNA expression levels in PBMCs of FIP and SPF cats. PBMCs (2 × 106 cells) were collected from FIP and SPF cats, and the Blimp-1 mRNA was detected by RT-PCR. Blimp-1 mRNA was quantitatively analyzed in terms of their relative density compared to that of the mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH

Partial base sequence analysis of BAFF cDNA, deduction of amino acid sequence, and comparison with other animal species

IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF are known as B-cell differentiation/survival factors. We investigated whether these factors in macrophages were increased in FIP cats by measuring mRNA expression. Since the nucleotide sequence of feline BAFF mRNA has not yet been determined, we partially sequenced the cDNA of BAFF mRNA.

The sequences of mouse (GenBank accession number: NM_033622), human (NM_006573), and bovine (XM_864542) BAFF mRNA have been determined. Primers corresponding to a highly conserved region were prepared for the detection of feline BAFF mRNA (Table 1). Using these primers, RT-PCR of PBMCs from FIP cats was performed, and a 164-bp band was specifically amplified. This amplified DNA was partially sequenced (data not shown), and the amino acid sequence was deduced from this. Homologies among the partial nucleotide sequences of feline, canine, bovine, mouse, and human BAFF mRNA and their deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Table 2.

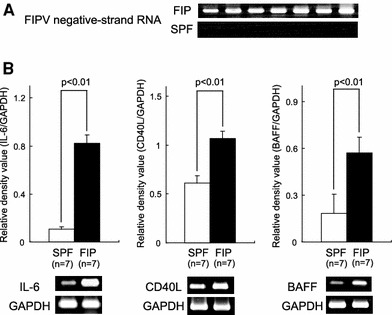

Measurement of FCoV N gene expression and IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression in alveolar macrophages of SPF and FIP cats

The production of B-cell differentiation/survival factors in FIP cats was investigated. Macrophages, one of the target cells of FIPV, were collected from FIP cats. The IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels in these cells were measured by RT-PCR and compared to those in SPF cats.

Virus replication in macrophages was investigated in FIP cats by measuring FIPV negative-strand RNA expression. In all FIP cats investigated, FIPV negative-strand RNA was expressed in alveolar macrophages (Fig. 4a). When the mRNA expression levels of B-cell differentiation/survival factors were measured, expression of IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA was significantly enhanced in FIP cats compared to SPF cats (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

FCoV N gene, IL-6, CD40L and BAFF mRNA expression levels in alveolar macrophages of FIP and SPF cats. a Alveolar macrophages (2 × 106 cells) were collected from FIP and SPF cats, and the FIPV negative-strand RNA was detected by RT-PCR. b Alveolar macrophages (2 × 106 cells) were collected from FIP and SPF cats, and IL-6, CD40L and BAFF mRNA was detected by RT-PCR. IL-6, CD40L and BAFF mRNA were quantitatively analyzed in terms of their relative density compared to that of the mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH

Relationship between FIPV replication and IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels in alveolar macrophages

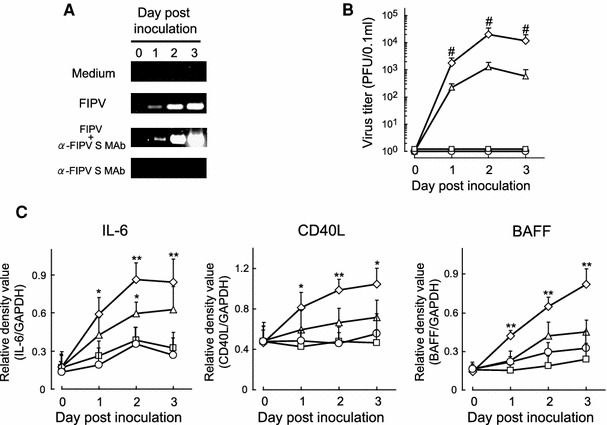

To investigate the relationship between FIPV replication and B-cell differentiation/survival factor production in macrophages, alveolar macrophages from SPF cats were inoculated with FIPV alone or a mixture of FIPV and anti-FIPV S MAb (MAb 6-4-2). The culture supernatant and cells were collected every 24 h for 3 days, and FIPV replication and B-cell differentiation/survival factor production were measured. In the measurement of FIPV replication, the virus titer in the macrophage culture supernatant was measured by the plaque method, and intracellular virus production was measured using FIPV negative-strand RNA expression as an index. To assess B-cell differentiation/survival factor production, the IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels in the cells were measured. FIPV negative-strand RNA was strongly expressed in macrophages inoculated with a mixture of FIPV and anti-FIPV S MAb compared to that in macrophages inoculated with the virus alone, and the virus titer in the culture supernatant was also significantly higher (Fig. 5a and b). The mRNA expression levels of all B-cell differentiation/survival factors, IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF, were also significantly increased in macrophages inoculated with the mixture (Fig. 5c), suggesting that virus production increased in ADE macrophages, in which B-cell differentiation/survival factor production also increased.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between FIPV replication and IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels in alveolar macrophages: SPF cat-derived alveolar macrophages (2 × 106 cells) were cultured with medium alone, FIPV, FIPV + anti-FIPV S MAb, or anti-FIPV MAb alone. The cells and culture supernatant were collected every 24 h thereafter. Intracellular FIPV negative-strand RNA was measured by RT-PCR (a), and the virus titer in the culture supernatant was measured by the plaque method (b). The intracellular IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels were also measured by RT-PCR (c). IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA were quantitatively analyzed in terms of their relative density compared to that of the mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH (n = 8). Circle medium, triangle FIPV, diamond FIPV + anti-FIPV S MAb, square anti-FIPV S MAb, # P < 0.01 versus FIPV, **P < 0.01 versus medium, *P < 0.05 versus medium

Discussion

In FIP cats, the gamma-globulin level increases, and immune-complex-mediated vasculitis develops, suggesting that overproduced antibodies are closely involved in the pathogenesis of FIP. However, only a few studies on B-cell characteristics and their activation mechanism after FIPV infection in FIP cats have been reported.

Here, we show that the ratio of sIg-positive, CD21-negative cells increases in PBMCs of FIP cats, and correlates with the albumin-to-globulin ratio in plasma samples. We also show that the Blimp-1 mRNA expression level is significantly elevated in PBMCs from FIP cats. Tedder et al. [34] reported that CD21 molecules disappeared from the cell surface, when B-cells differentiated into antibody-producing cells. Shapiro-Shelef and Calame [28] reported that Blimp-1 is the master gene that causes the final differentiation of B-cells into plasma cells. Thus, the number of plasma cells may increase in the peripheral blood of FIP cats. Plasma cells are mainly present in the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes, but not in peripheral blood. An increase in plasma cells in peripheral blood may be evidence of enhanced B-cell activation.

B-cells are stimulated by antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells and macrophages) in lymphatic tissues, and start to differentiate into plasma cells. For B-cells to differentiate into plasma cells, various factors (cytokines, antigens, etc.) are necessary. We focused on IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF as B-cell differentiation/survival factors. IL-6 is involved in the differentiation of B-cells into plasma cells, and signal transmission via the IL-6 receptor inhibits B-cell apoptosis [7, 18, 36]. CD40L inhibits the induction of B-cell apoptosis by binding to CD40 expressed on the B-cell surface, activating B-cells [3, 16, 17, 20]. BAFF induces an apoptosis-inhibitory gene, Bcl-2, by binding to the BAFF receptor expressed on B-cells, inhibiting B-cell apoptosis [6, 22]. We clarified that IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression was increased in macrophages in FIP cats. The IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels were also increased with virus replication in macrophages inoculated with FIPV, suggesting that FIPV replication induced BAFF, IL-6, and CD40L production in macrophages of FIP cats, and these factors promoted B-cell differentiation into plasma cells.

Virus production and IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression were markedly enhanced in ADE macrophages in vitro compared to macrophages inoculated with the virus alone. We reported previously that when the FIPV antigen was detected by the fluorescent antibody method, 10–20% of cells were positive when SPF cat-derived alveolar macrophages were inoculated with FIPV + anti-FIPV S MAb, whereas 1–2% of cells were positive when alveolar macrophages were inoculated with FIPV [12, 15]. It seems that the increased number of virus-infected macrophages leads to the over-expression of B-cell differentiation/survival factor mRNA in macrophages. However, there is no evidence that this hypothesis is correct. A continued examination of the mechanism of ADE activity in FIPV infection would strengthen this hypothesis.

We reported previously that ADE activity in FIPV infection of feline macrophages caused overproduction of TNF-alpha, which may lead to serious FIP symptoms [31]. The increased IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF mRNA expression levels in ADE macrophages may also be closely involved in aggravation of pathogenesis, as well as TNF-alpha. That is, our data suggest that FIPV re-infection induces ADE and advances FIP development in cats. However, Addie et al. [2]reported that FCoV re-infection of anti-FCoV antibody-positive domestic cats might not result in the development of ADE. Although the details are unclear, differences in the immunological condition of FCoV-infected cats may be the reason why the phenomenon noted in ADE does not occur in domestic cats. It is necessary to analyze mechanism of ADE in detail.

Of the B-cell differentiation/survival factors measured, significant elevation of the ascitic and serum IL-6 levels in FIP cats has been reported [8]. Regarding CD40L, tissue deposition of immune-complexes, similar to that in FIP, is involved in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjogren’s disease, in which a significantly increased serum CD40L level has been reported [9]. Similarly, increased levels of immune-complexes in the blood of mice induced to overexpress BAFF have been reported [21]. Therefore, it is easily predicted that IL-6, CD40L, and BAFF are involved in the development of immune-complex-mediated vasculitis. IL-6 has also been reported to induce Blimp-1 expression in B-cells, mainly by activating STAT3 [19], suggesting that IL-6 is involved in the enhanced Blimp-1 mRNA expression in PBMCs in FIP cats.

In this study, we showed that virus-infected macrophages overproduce B-cell differentiation/survival factors and that these factors act on B-cells and promote B-cell differentiation into plasma cells in FIPV-infected cats. These findings may be important for the elucidation of the pathogenesis of FIP.

References

- 1.Addie DD, Jarrett O. Feline coronavirus infection. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Pennsylvania: WB Saunders; 1998. pp. 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addie DD, Toth S, Murray GD, Jarrett O. Risk of feline infectious peritonitis in cats naturally infected with feline coronavirus. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage RJ, Fanslow WC, Strockbine L, Sato TA, Clifford KN, Macduff BM, Anderson DM, Gimpel SD, Davis-Smith T, Maliszewski CR, Clark EA, Smith CA, Grabstein KH, Cosman D, Spriggs MK. Molecular and biological characterization of a murine ligand for CD40. Nature. 1992;357:80–82. doi: 10.1038/357080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avery PR, Hoover EA. Gamma interferon/interleukin 10 balance in tissue lymphocytes correlates with down modulation of mucosal feline immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:4011–4019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4011-4019.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corapi WV, Olsen CW, Scott FW. Monoclonal antibody analysis of neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis virus. J Virol. 1992;66:6695–6705. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6695-6705.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craxton A, Magaletti D, Ryan EJ, Clark EA. Macrophage- and dendric cell-dependent regulation of human B cell proliferation requires the TNF family ligand BAFF. Blood. 2003;101:4464–4471. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolcetti R, Boiocchi M. Cellular and molecular bases of B-cell clonal expansions. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goitsuka R, Ohashi T, Ono K, Yasukawa K, Koishibara Y, Fukui H, Ohsugi Y, Hasegawa A. IL-6 activity in feline infectious peritonitis. J Immunol. 1990;144:2599–2603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goules A, Tzioufas AG, Manousakis MN, Kirou KA, Crow MK, Routsias JG. Elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) in serum of patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2006;26:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halstead SB. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2003;60:421–467. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(03)60011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrewegh AA, Vennema H, Horzinek MC, Rottier PJ, de Groot RJ. The molecular genetics of feline coronaviruses: comparative sequence analysis of the ORF7a/7b transcription unit of different biotypes. Virology. 1995;212:622–631. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohdatsu T, Nakamura M, Ishizuka Y, Yamada H, Koyama H. A study on the mechanism of antibody-dependent enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection in feline macrophages by monoclonal antibodies. Arch Virol. 1991;120:207–217. doi: 10.1007/BF01310476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohdatsu T, Okada S, Koyama H. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against feline infectious peritonitis virus type II and antigenic relationship between feline, porcine and canine coronaviruses. Arch Virol. 1991;117:85–95. doi: 10.1007/BF01310494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hohdatsu T, Yamada H, Ishizuka Y, Koyama H. Enhancement and neutralization of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection in feline macrophages by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies recognizing different epitopes. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37:499–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb03242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hohdatsu T, Tokunaga J, Koyama H. The role of IgG subclass of mouse monoclonal antibodies in antibody-dependent enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection of feline macrophages. Arch Virol. 1994;139:273–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01310791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hokazono Y, Adachi T, Wabl M, Tada N, Amagasa T, Tsubata T. Inhibitory co-receptors activated by antigens but not by anti-immunoglobulin heavy chain antibodies install requirement of co-stimulation through CD40 for survival and proliferation of B cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1835–1843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holder MJ, Wang H, Milner AE, Casamayor M, Armitage R, Spriggs MK, Fanslow WC, MacLennan IC, Gregory CD, Gordon J. Suppression of apoptosis in normal and neoplastic human B lymphocytes by CD40 ligand is independent of Bcl-2 induction. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2368–2371. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawano MM, Mihara K, Huang N, Tsujimoto T, Kuramoto A. Differentiation of early plasma cells on bone marrow stromal cells requires Interleukin-6 for escaping from apoptosis. Blood. 1995;85:487–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein B, Tarte K, Jourdan M, Mathouk K, Moreaux J, Jourdan E, Legouffe E, De Vos J, Rossi JF. Survival and proliferation factors of normal and malignant plasma cells. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:106–113. doi: 10.1007/BF02983377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mach F, Schonbeck U, Sukhova GK, Bourcier T, Bonnefoy JY, Pober JS, Libby P. Functional CD40 ligand is expressed on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages: implications for CD40-CD40 ligand signaling in atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, Ambrose C, Baetscher M, Schneider P, Tschopp J, Browning JL. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1697–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsushita T, Sato S. The role of BAFF in autoimmune disease. Jpn J Clin Immunol. 2005;28:333–342. doi: 10.2177/jsci.28.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen CW, Corapi WV, Ngichabe CK, Baines JD, Scott FW. Monoclonal antibodies to the spike protein of feline infectious peritonitis virus mediate antibody-dependent enhancement of infection of feline macrophages. J Virol. 1992;66:956–965. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.956-965.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen CW. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus: molecular biology, immunopathogenesis, clinical aspects, and vaccination. Vet Microbiol. 1993;36:1–37. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90126-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen NC, Boyle JF. Immunologic phenomena in the effusive form of feline infectious peritonitis. Am J Vet Res. 1980;41:868–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poland AM, Vennema H, Foley JE, Pedersen NC. Two related strains of feline infectious peritonitis virus isolated from immunocompromised cats infected with a feline enteric coronavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3180–3184. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3180-3184.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rottier PJ, Nakamura K, Schellen P, Volders H, Haijema BJ. Acquisition of macrophage tropism during the pathogenesis of feline infectious peritonitis is determined by mutations in the feline coronavirus spike protein. J Virol. 2005;79:14122–14130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14122-14130.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro-Shelef M, Calame K. Regulation of plasma-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:230–242. doi: 10.1038/nri1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoddart CA, Scott FW. Intrinsic resistance of feline peritoneal macrophages to coronavirus infection correlates with in vivo virulence. J Virol. 1989;63:436–440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.436-440.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takano T, Hohdatsu T, Hashida Y, Kaneko Y, Tanabe M, Koyama H. A “possible” involvement of TNF-alpha in apoptosis induction in peripheral blood lymphocytes of cats with feline infectious peritonitis. Vet Microbiol. 2007;119:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takano T, Hohdatsu T, Toda A, Tanabe M, Koyama H. TNF-alpha, produced by feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV)-induced macrophages, upregulates expression of type II FIPV receptor feline aminopeptidase N in feline macrophages. Virology. 2007;364:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takano T, Katada Y, Moritoh S, Ogasawara M, Satoh K, Satoh R, Tanabe M, Hohdatsu T. Analysis of the mechanism of antibody-dependent enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: aminopeptidase N is not important and a process of acidification of the endosome is necessary. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1025–1029. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda A, Sweet RW, Ennis FA. Two receptors are required for antibody- dependent enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: CD4 and Fc gamma R. J Virol. 1990;64:5605–5610. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5605-5610.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tedder TF, Clement LT, Cooper MD. Expression of C3d receptors during human B cell differentiation: immunofluorescence analysis with the HB-5 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1984;133:678–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tirado SM, Yoon KJ. Antibody-dependent enhancement of virus infection and disease. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:69–86. doi: 10.1089/088282403763635465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tumang JR, Hsia CY, Tian W, Bromberg JF, Liou HC. IL-6 rescues the hyporesponsiveness of c-Rel deficient B cells independent of Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, and Bcl-2. Cell Immunol. 2002;217:47–57. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vennema H, Poland A, Foley J, Pedersen NC. Feline infectious peritonitis viruses arise by mutation from endemic feline enteric coronaviruses. Virology. 1998;243:150–157. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]