Abstract

A 5-year-old female Yorkshire terrier dog died a few days following hernia and ovariohysterectomy surgeries. Necropsy performed on the dog revealed that the surgeries were not the cause of death; however, degenerative viral hepatitis, showing intranuclear inclusion bodies in hepatic cells, was observed in histopathologic examination. Several diagnostic methods were used to screen for the cause of disease, and minute virus of canines (MVC) was detected in all parenchymal organs, including the liver. Other pathogens that may cause degenerative viral hepatitis were not found. Infection with MVC was confirmed by in situ hybridization, which revealed the presence of MVC nucleic acid in the liver tissue of the dog. Through sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the nearly complete genome sequence, the strain was found to be distinct from other previously reported MVC strains. These results indicate that this novel MVC strain might be related to degenerative viral hepatitis in dogs.

Keywords: Minute virus of canines, Canine, Hepatitis, Phylogenetic analysis

Viruses the family Parvoviridae are currently categorized into two subfamilies: Densovirinae and Parvovirinae, members of which infect in-vertebrate and vertebrate hosts, respectively [3, 8]. The subfamily Parvovirinae is further divided into eight genera: Amdoparvovirus, Aveparvovirus, Bocaparvovirus, Copiparvovirus, Dependoparvovirus, Erythroparvovirus, Protoparvovirus, and Tetraparvovirus [2]. The genus Bocaparvovirus contains small, non-enveloped, autonomously replicating, single-stranded DNA viruses with an icosahedral capsid. Bocaparvoviruses are unique among parvoviruses, as they contain a third open reading frame (ORF) between the regions encoding the non-structural and structural proteins, and they have a genome length of approximately 5.4 kb. The genus was originally named according to its initial two members, bovine parvovirus (BPV) and minute virus of canines (MVC) [1, 13, 18, 19].

Minute virus of canines, also known as canine minute virus or canine parvovirus type 1, is an autonomous parvovirus of dogs that is genetically and antigenically unrelated to canine parvovirus type 2, which belongs to a separate genus in the family Parvoviridae and is a common agent of canine hemorrhagic gastroenteritis [17]. MVC was first discovered in Germany in 1967 in feces samples of clinically healthy dogs [5, 12]. Initially, MVC was not thought to cause disease; however, several studies, including experimental infections, revealed its role as a pathogen in newborn pups and canine fetuses [4, 6]. Recently, MVC was reported to be associated with neurological disease in dogs of various ages [7] and with severe gastroenteritis in an elderly dog [15].

A seroprevalence study undertaken in 2003 showed an 11.8 % MVC-positive rate for Korean canines [9], and an MVC strain was isolated from a Korean dog in 2004 [14]. Since then, MVC has not been reported in Korea for over 10 years, but it has been reported infrequently in other areas of Asia, including Japan and China [15, 17]. The present study describes a previously unreported MVC strain, isolated from a canine in Korea, and we have analyzed its genetic relationship to other bocaparvoviruses.

A five-year-old female Yorkshire terrier dog underwent a hernia operation and ovariohysterectomy on Dec 30, 2014. Five days after surgery, the dog began to experience loss of appetite and vomiting. The dog died on Jan 8, 2015, following symptoms of hypothermia, bloody vomiting, and bloody diarrhea.

The dog was submitted to the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency for diagnostic examination. A full necropsy was performed; brain, lung, kidney, liver, spleen, lymph node, heart, and intestine were among the tissues collected, which were subsequently fixed in 10 % buffered formalin, dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions, and embedded in paraffin wax. Four-micrometer serial sections from the paraffin-embedded organs were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analysis.

For the generation of an MVC-specific in situ probe, PCR labeling with a PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, a specific region (nucleotides 606–1112) of the NS1 gene of the 15D009 strain was amplified by PCR, using NS1 forward (5’ AACGCGATTTGCACCTTCAT 3’) and NS1 reverse (5’ CATCAAACATTTCTCCGGCA 3’) primers. The PCR product was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) and subsequently used as a hybridization probe. Using this probe, the tissues of parenchymal organs taken from the infected dogs were investigated for the presence of MVC nucleic acid. To detect MVC DNA, additional paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4-μm thickness and hybridized in situ using a fully automated system (NexES IHC instrument; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA) and a DAB detection system (Ventana Medical Systems Inc.). The tissue sections were deparaffinized (standard xylene and industrial methanol) and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Tissues were then permeabilized by incubation in 0.1 M HCl containing 1 mg of pepsin per mL for 20 min at 37 °C, followed by denaturation at 70 °C for 10 min before hybridization with the DIG-labeled riboprobes at 65 °C for 6 h. After hybridization, samples were washed twice 0.1× SSC at 75 °C for 6 min, followed by PBS at room temperature for 5 min. After hybridization, slides were incubated with QDs 605–conjugated anti-DIG antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min and then rinsed twice in PBS for 5 min. All tissue sections were mounted with coverslips using 90 % (v/v) glycerol/PBS mounting solution. The DAB detection system was then used to detect antibody binding. Finally, sections were incubated at 37 °C and then counterstained with hematoxylin and post-counterstained with bluing reagent.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed for genetic diagnosis. Extraction of viral RNA and DNA from organ tissue was performed using an Inclone Mini Extraction Kit (Inclone Biotech Co., Yongin, Gyeonggi, 488161, Korea), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Canine parvovirus types 1 and 2 (CPV-1, 2), canine distemper virus (CDV), and canine influenza virus (CIV), were examined using a virus detection kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Sungnam, Gyeonggi, 462120, Korea). Canine herpes virus (CHV) and canine adenovirus types 1 and 2 (CAdV-1 and, -2) were amplified by PCR, using a HotStart PCR Premix (iMOD, Hanam, Gyeonggi, 465010, Korea). Canine corona virus (CCV) and canine parainfluenza virus (CPIV) were screened using an RT-PCR one-step kit (iMOD). PCR products (10 μL) were subjected to electrophoresis in 1.5 % agarose gels at 135 V for 20 min to visualize the amplified DNA. A molecular weight marker was run with the samples to determine the length of the amplified product. Bands were visualized under ultraviolet illumination after ethidium bromide staining and photographed using an ultraviolet gel imaging system.

For genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, sequence-specific oligonucleotides were designed based on the conserved regions of several published MVCs [15–17]. The amplified PCR products were purified using an agarose gel DNA extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea) and cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The cloned plasmids were purified and sequenced using T7 and SP6 primers, a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and an automated DNA sequencer (ABI 3130XL Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems). All nucleotide sequences were confirmed by three or more independent, bi-directional sequencing runs. Nucleotide and putative amino acid sequence alignments were generated using the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The nearly complete sequence of the MVC genome was deposited in the GenBank database, under accession number KT241026. This sequence was compared to those of previously reported MVCs and bocaparvoviruses from other species at both the nucleotide and amino acid level, using orthologous sequences available in GenBank. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using BioEdit and Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) 4.0 software, with bootstrap values calculated from 1,000 replicates. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic algorithm was used to construct phylogenetic trees.

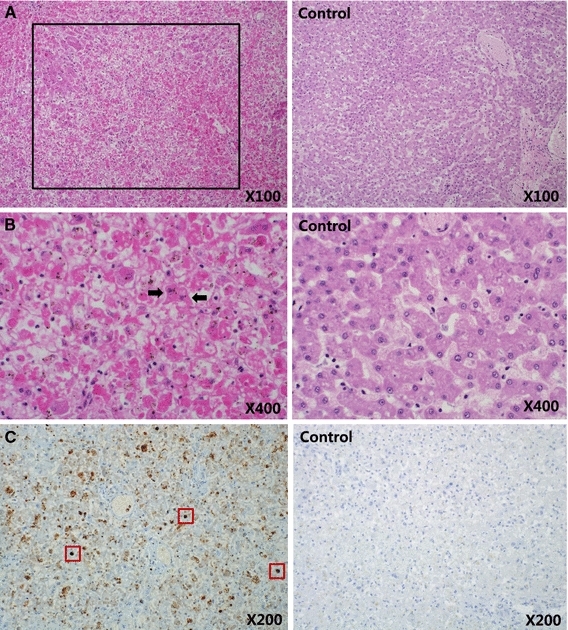

From post-mortem examination, the immediate and surrounding areas of the surgical incisions showed no indication of surgical complications. The gastrointestinal tract was sparsely filled with fluid contents, and liver and spleen damage was evident. Histopathologic examination revealed massive hepatic necrosis and basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies in degenerated hepatic cells (Fig. 1). There were no other macroscopic or significant histological findings in the other organs.

Fig. 1.

Massive hepatic necrosis (black box) (A, ×100). Basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies (arrows) were observed in degenerated hepatic cells (B, ×400). The nucleic acid of MVC (dark brown staining, red boxes) was detected in liver tissue (C, ×200) via in situ hybridization (color figure online)

On analyzing the in situ hybridization images, hepatic cells surrounding the damaged regions and intranuclear inclusion bodies were found positive for MVC nucleic acid (Fig. 1). In situ hybridization in other tissues also revealed cells that were positive for MVC nucleic acid; however, with the exclusion of the liver, there was no evidence of lesions in any other organs. Therefore, it was difficult to establish a correlation between the results of in situ hybridization for these organs and the presence of disease in the present case.

By using PCR and RT-PCR, CPV-2, CAdV-1,2, CDV, CIV, CHV, CCV, and CPIV were not detected; however, positive PCR products of the expected size of 406 bp, corresponding to MVC, were detected in samples of the brain, lung, kidney, liver, spleen, lymph node, heart, and intestinal tissue.

The isolated MVC strain, designated 15D009, was sequenced and aligned with the other MVC strains obtained from GenBank, using Bioedit. The MVC 15D009 strain has a 5,101-nucleotide-long genome. The non-coding region of the 15D009 strain on the left-hand side (LHS) terminus, located at the 5′-end of positive-sense ssDNA genomes, was 253 nucleotides in length. The right-hand side (RHS) non-coding region of the 15D009 strain, found at the 3′ end of positive-sense ssDNA genomes, was 52 nucleotides in length. However, the very end of the 3′ and 5′ termini of this genome could not be definitively sequenced, presumably because of its peculiar hairpin structures, which are also present in other parvovirus genomes [16]. ORF1 of the 15D009 strain encodes a 776-aa non-structural (NS) protein, which is 2–60 aa longer than the NS protein of other MVC strains. ORF2 and ORF3 of the 15D009 strain encode a 703-aa protein that overlaps with the VP1/VP2 capsid protein, and a 186-aa NP1 protein, respectively.

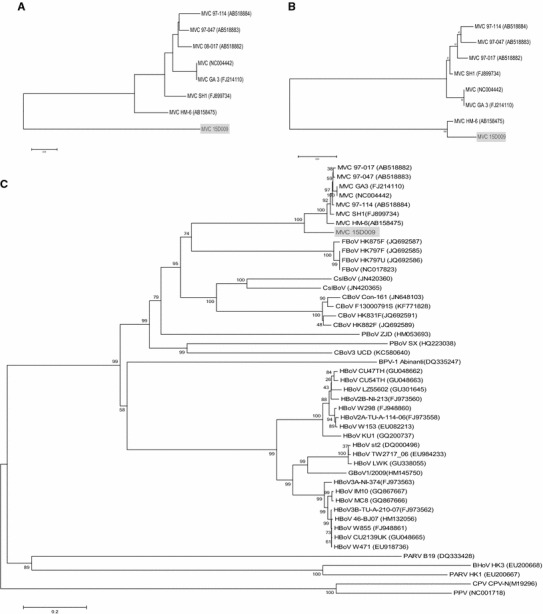

The NS1 region of 15D009 strain shared 81.7-88.4 % nucleotide and 86.7-93.5 % amino acid sequence identity with the other MVC strains (Table 1). These values are lower than the mean nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity values for the NS1 regions of other MVC strains (approximately 94.7 % and 95.0 %, respectively). The VP1/VP2 region of 15D009 strain shared 86.3-86.8 % nucleotide and 95.1-96.4 % amino acid sequence identity with other MVC strains (Table 1), which is also lower than the mean nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity values for the VP1/VP2 region of other MVC strains (approximately 97.8 % and 98.6 %, respectively). Phylogenetic analysis based on these NS1 and VP1/VP2 regions also showed that the 15D009 strain formed a distinct branch that was separate from the other previous MVC strains. This indicates that this strain is distinct from these previously isolated strains (Fig. 2). However, the NP1 region of the 15D009 strain showed greater nucleotide and amino acid sequence similarity to that of the HM-6 strain (AB158475), which was isolated from a Korean dog in 2004 (99.1 % and 99.4 %, respectively), compared to those of the other MVC strains (mean similarities of 90.9-91.4 % and 93.0 %, respectively) (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis based on the NP1 region of the MVC strains also showed that the 15D009 and HM-6 strains fell into the same cluster, which is distinct from other MVC strains (Fig. 2). The high level of nucleotide and amino acid sequence similarity in the NP1 region between these two Korean strains implies that the 15D009 strain could be a mutated strain of HM-6 or an endemic strain from Korea that has not been isolated previously. In addition, the coding region of 15D009 shared 84.1-87.8 % nucleotide sequence identity to the other MVC strains (Table 1), and this value is lower than the mean nucleotide sequence identity of the coding region of the other MVC strains (approximately 96.2 %). Phylogenetic analysis based on the complete sequence of the 15D009 strain indicated that this strain could be correctly classified as an MVC strain, although it forms a distinct branch on phylogenetic trees when analyzed with respect to the NS1 and VP1/VP2 regions. Interestingly, the MVC strains, including the 15D009 strain, are more closely related to feline bocaviruses than the novel canine bocaviruses (Fig. 2). This observation supports the possibility of a common origin and cross-species transmission between MVC and feline bocavirus.

Table 1.

Nucleotide and putative amino acid sequence identities of MVC (15D009) and other reference MVC strains from several countries*

| Gene region | Nucleotide sequence identity (%)/Amino acid sequence identity (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVC (USA) | MVC SH1 (China) | MVC 97-114 (Japan) | MVC 97-047 (Japan) | MVC 08-017 (Japan) | MVC GA3 (USA) | MVC HM-6 (South Korea) | ||

| Nonstructural | NS1 | 81.0/86.1 | 88.3/93.5 | 88.2/93.5 | 88.2/93.3 | 88.4/93.5 | 88.0/93.4 | 81.7/86.7 |

| NP1 | 91.2/93.0 | 91.4/93.0 | 90.9/93.0 | 91.2/93.0 | 91.2/93.0 | 91.2/93.0 | 99.1/99.4 | |

| Structural | VP1/VP2 | 86.3/96.0 | 86.7/96.3 | 86.6/96.4 | 86.6/96.4 | 86.6/95.8 | 86.3/96.1 | 86.8/95.1 |

| Coding region | NS1-VP2 | 84.1 | 87.8 | 87.6 | 87.7 | 87.8 | 87.5 | 85.2 |

Bold value indicates amino acid sequence identity

* Reference MVC strains include MVC USA (accession no. NC004442), MVC SH1 (accession no. FJ899734), MVC 97-114 (accession no. AB518884), MVC 97-047 (accession no. AB518883), MVC 08-017 (accession no. AB518882), MVC GA3 (accession no. FJ214110), MVC HM-6 (accession no. AB158475), and MCV 15D009 (accession no. KT241026)

Fig. 2.

(a) Phylogenetic relationship between the NS1 or VP1/VP2 gene nucleotide sequences from the different MVC strains. (b) Phylogenetic relationship between the NP1 gene nucleotide sequences from the different MVC strains. (c) Phylogenetic analysis of complete genome sequences of MVC strains, including 15D009 and other bocaparvoviruses with genome sequences available. GenBank accession numbers are in parentheses; the accession number of MVC 15D009 is KT241026. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining algorithm, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. BHoV, bovine hokobirus; BPV, bovine parvovirus; CBoV, canine bocavirus; CMV, canine minute virus; CPV, canine parvovirus; CSlBoV, California sea lion bocavirus; FBoV, feline bocavirus; GBoV, gorilla bocavirus; HBov, human bocavirus, PARV, human parvovirus; PBoV, porcine bocavirus; PPV, porcine parvovirus

In conclusion, our results indicate that the MVC 15D009 strain is a possible cause of degenerative viral hepatitis in dogs. Although liver degeneration in canines has also been described at post-mortem examination of a pup infected with MVC [6], and a novel bocavirus (KC580640) that was highly divergent from known MVC strains has been isolated from canine liver [11], hepatitis with evidence of intranuclear inclusion bodies that correspond to MVC infection has not yet been reported. Therefore, the present study suggests two possible mechanisms for the observation of hepatic intranuclear inclusion bodies following infection with the novel MVC 15D009 strain. First, there is the possibility of pathogenic variation between the 15D009 and other MVC strains, based on differences in nucleotide and amino acid sequences. The 15D009 strain showed comparatively low nucleotide and amino acid sequence similarity to other MVC strains, except in the NP1 region of the HM-6 strain, and the region related to pathogenicity might be altered, resulting in an acquired ability to cause hepatitis. The second possibility is that an immunocompromised state of the host animal might affect virulence. Generally, the pathogenic potential of MVC for adult dogs has been considered minimal [1, 4, 5, 13]. However, the host animal in the present study had surgery a few days before presenting with symptoms, and this procedure may have weakened the host immune system, which can be influenced by factors such as stress, anesthetic effects, or the effects of other drugs. This weakened immunity might explain the occurrence of hepatitis; in fact, simultaneous human bocavirus infection and hepatitis has been reported in a boy with severe T-cell immunodeficiency [10]. Further studies, such as isolation of the 15D009 strain and a subsequent animal inoculation tests, are required to clarify the exact relationship between this strain and hepatitis and to determine the distribution, diversity, and pathogenesis of MVC in dogs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, Anyang, Gyeonggi, Republic of Korea.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any animal studies that were performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Binn LN, Lazar EC, Eddy GA, Kajima M. Recovery and characterization of a minute virus of canines. Infect Immun. 1970;1:503–508. doi: 10.1128/iai.1.5.503-508.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodewes R, Lapp S, Hahn K, Habierski A, Forster C, Konig M, Wohlsein P, Osterhaus ADME, Baumgartner W. Novel canine bocavirus strain associated with severe enteritis in a dog litter. Vet Microbiol. 2014;174:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown KE. The expanding range of parvoviruses which infect humans. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:231–244. doi: 10.1002/rmv.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmichael LE, Schlafer DH, Hashimoto A. Pathogenicity of minute virus of canines (MVC) for the canine fetus. Cornell Vet. 1991;81:151–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmichael LE, Schlafer DH, Hashimoto A. Minute virus of canines (MVC, canine parvovirus type-1): pathogenicity for pups and seroprevalence estimate. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994;6:165–174. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decaro N, Amorisco F, Lenoci D, Lovero A, Colaianni ML, Losurdo M, Desario C, Martella V, Buonavoglia C. Molecular characterization of Canine minute virus associated with neonatal mortality in a litter of Jack Russell terrier dogs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:755–758. doi: 10.1177/1040638712445776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eminaga S, Palus V, Cherubini GB. Minute virus as a possible cause of neurological problems in dogs. Vet Rec. 2011;168:111–112. doi: 10.1136/vr.d531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA. Virus taxonomy: eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. California: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang HK, Tohya Y, Han KY, Kim TJ, Song CS, Mochizuki M. Seroprevalence of canine calicivirus and canine minute virus in the Republic of Korea. Vet Rec. 2003;153:150–152. doi: 10.1136/vr.153.5.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kainulainen L, Waris M, Soderlund-Venermo M, Allander T, Hedman K, Ruuskanen O. Hepatitis and human bocavirus primary infection in a child with T-cell deficiency. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:4104–4105. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01288-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L, Pesavento PA, Leutenegger CM, Estrada M, Coffey LL, Naccache SN, Samayoa E, Chiu C, Qiu J, Wang C, Deng X, Delwart E. A novel bocavirus in canine liver. Virol J. 2013;10:54. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manteufel J, Truyen U. Animal bocaviruses: a brief review. Intervirology. 2008;51:328–334. doi: 10.1159/000173734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mochizuki M, Hashimoto M, Hajima T, Takiguchi M, Hashimoto A, Une Y, Roerink F, Ohshima T, Parrish CR, Carmichael LE. Virologic and serologic identification of minute virus of canines (canine parvovirus type 1) from dogs in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3993–3998. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.3993-3998.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohshima T, Kishi M, Mochizuki M. Sequence analysis of an Asian isolate of minute virus of canines (canine parvovirus type 1) Virus Genes. 2004;29:291–296. doi: 10.1007/s11262-004-7430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohshima T, Kawakami K, Abe T, Mochizuki M. A minute virus of canines (MVC: canine bocavirus) isolated from an elderly dog with severe gastroenteritis, and phylogenetic analysis of MVC strains. Vet Microbiol. 2010;145:334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz D, Green B, Carmichael LE, Parrish CR. The canine minute virus (minute virus of canines) is a distinct parvovirus that is most similar to bovine parvovirus. Virology. 2002;302:219–223. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shan TL, Cui L, Dai XQ, Guo W, Shang XG, Yu Y, Zhang W, Kang YJ, Shen Q, Yang ZB, Zhu JG, Hua XG. Sequence analysis of an isolate of minute virus of canines in China reveals the closed association with bocavirus. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37:2817–2820. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spahn GJ, Mohanty SB, Hetrick FM. Experimental infection of calves with hemadsorbing enteric (HADEN) virus. Cornell Vet. 1966;56:377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storz J, Leary JJ, Carlson JH, Bates RC. Parvoviruses associated with diarrhea in calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978;173:624–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]